Abstract

Merozoite surface protein 2 (MSP2), one of the most abundant proteins on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites, is a promising malaria vaccine candidate. MSP2 is intrinsically unstructured and forms amyloid-like fibrils in solution. As this propensity of MSP2 to form fibrils in solution has the potential to impede its development as a vaccine candidate, finding an inhibitor that inhibits fibrillogenesis may enhance vaccine development. We have shown previously that EGCG inhibits the formation of MSP2 fibrils. Here we show that EGCG can alter the β-sheet-like structure of the fibril and disaggregate pre-formed fibrils of MSP2 into soluble oligomers. The fibril remodelling effects of EGCG and other flavonoids were characterized using Thioflavin T fluorescence assays, electron microscopy and other biophysical methods.

Keywords: malaria, vaccine, MSP2, amyloid, flavonoid, EGCG

1. Introduction

Merozoite surface protein 2 (MSP2) is a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein expressed abundantly on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites [1, 2]. MSP2 was shown to be a promising malaria vaccine candidate in a Phase 2 trial in Papua New Guinea [3]. Full-length MSP2 has the characteristics of an intrinsically unstructured protein and forms amyloid-like fibrils in solution under physiological conditions [4, 5]. These fibrils have a proteinase K-resistant core comprised of the N-terminal conserved region of MSP2 [4] and peptides corresponding to this region of the protein form fibrils similar to those formed by full-length MSP2 [6, 7]. Oligomers containing β-strand interactions similar to those in amyloid fibrils may be a component of the fibrillar surface coat on P. falciparum merozoites. This propensity of MSP2 to form fibrils in solution, and the unstable nature of these fibrils, are potential problems for the development of a vaccine incorporating this antigen. Therefore, the identification of small molecules that either specifically inhibit fibril formation or disaggregate preformed fibrils could facilitate the development of MSP2 as a vaccine candidate.

Flavonoids have been shown to inhibit fibrillogenesis by amyloidogenic proteins in vitro, in cell culture, and, recently, in vivo [8–10]. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) (Fig. S1), the most abundant flavonoid in green tea, has received particular attention for its ability to inhibit fibrillogenesis [8, 11, 12]. Other flavonoids with potent antiamyloidogenic activity are baicalein and resveratrol (Fig. S1). EGCG efficiently inhibits amyloid fibril formation by several amyloidogenic proteins involved in neurodegenerative diseases, including α-synuclein, Aβ and Huntington [8, 11, 13]; EGCG prevents fibril formation by redirecting these aggregation-prone proteins into off-pathway oligomers [8]. In a recent study, we showed that EGCG inhibits MSP2 fibril formation, and stabilizes soluble oligomers of MSP2 [14]. EGCG binds directly to MSP2 and blocks fibrillogenesis by preventing the conformational transition of MSP2 from a random coil to amyloidogenic β-sheet structure. In the presence of EGCG, MSP2 assembles into unstructured, SDS-stable MSP2 oligomers rather than β-sheet-rich aggregates. These findings raise the question of whether EGCG might also be able to disassemble pre-formed, β-sheet-rich MSP2 fibrils.

Recent studies have shown that EGCG can disaggregate and alter the structure of amyloid fibrils formed by α-synuclein, amyloid-β and IAPP [15, 16]. We have therefore investigated the ability of EGCG, baicalein and resveratrol to disaggregate and remodel amyloid-like fibrils formed by MSP2. Thioflavin T assays, electron microscopy and other biophysical methods have been used to explore the effects of these flavonoids in disaggregating pre-formed MSP2 fibrils.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Protein Expression and Purification

All of the studies described here were carried out with the recombinant FC27 allelic form of MSP2 expressed in E. coli. Two different constructs were used for the studies: C-terminal His6-tagged full-length FC27 MSP2 (FC27 MSP2-6H) and untagged full-length FC27 MSP2 (FC27 NT-MSP2). These constructs were purified using a strategy specific for recombinantly expressed unstructured proteins, as described previously [4, 5]. MSP2 fibrils were produced by incubating monomeric MSP2 (207 µM) in PBS at 37 °C for one week. The fibrils were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), ThT fluorescence assays and CD spectroscopy.

2.2. Thioflavin T Fluorescence Assays

Disaggregation kinetics of MSP2 fibrils in the presence of flavonoids were monitored using Thioflavin T (ThT) (Sigma), a fluorophore that has an increased fluorescence intensity when bound to amyloid fibrils [17]. To determine whether flavonoids can disassemble MSP2 fibrils, we measured changes in fluorescence intensity of ThT bound to both FC27 MSP2-6H and FC27 NT-MSP2 fibrils in the presence of the flavonoids. The flavonoids EGCG, baicalein and resveratrol were obtained from Sigma. EGCG stock solution (16 mM) was prepared in water and baicalein (40 mM) and resveratrol (40 mM) stock solutions were prepared in DMSO. These flavonoids are prone to auto-oxidation, so freshly prepared stocks solutions were used for most of the experiments. Reactions in 200 µL volumes were carried out in black 96-well microtitre plates (Nunc) containing 40 µM MSP2 fibrils and 30 µM ThT in PBS. ThT fluorescence was assayed at 5 min intervals for 25 min before the addition of flavonoids. Aliquots from flavonoid stocks were added to the wells to yield final concentrations of 40 and 400 µM for EGCG and 600 µM for baicalein and resveratrol. The final DMSO concentration in baicalein and resveratrol samples was 1.5% (v/v). Control MSP2 samples containing 1.5% (v/v) DMSO were also prepared. The microtitre plates were sealed with self-adhesive plate covers to reduce evaporation and ThT fluorescence was assayed at 30 min intervals following agitation (20 s) of the plate, using a SpectroMax M2 plate reader (Molecular devices) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 443 and 484 nm, respectively.

2.3. Electron Microscopy

TEM was used to characterise the morphology and size of MSP2 fibrils both in the presence and absence of flavonoids. Aliquots for TEM were taken from the ThT assay samples after incubation with the flavonoids for 24 h. Protein samples (10 µL) were applied to 400 mesh copper grids coated with a thin layer of carbon for 2 min. Excess material was removed by blotting and samples were negatively stained twice with 10 µL of a 2% w/v uranyl acetate solution (Electron Microscopy Services). The grids were air dried and viewed using a JEOL JEM-2010 transmission electron microscope operated at 80 kV.

2.4. SDS-PAGE and Nitroblue Tetrazolium Staining

Untreated and EGCG-treated MSP2 fibrils were analysed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions on 12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE (Invitrogen) gels and Coomassie stained. Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) (Sigma) staining was performed to detect protein-bound EGCG quinones, as described previously [14, 18]. To assess the effect of oxidized EGCG on MSP2 fibril disaggregation, MSP2 fibrils were incubated with EGCG in the presence of reduced glutathione (GSH). 20 µM FC27 MSP2-6H fibrils were incubated with 200 µM EGCG and 1 mM GSH for 2 days at 4°C on a rotator. These samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE as described above.

2.5. Size-Exclusion Chromatography

Size-exclusion chromatography was performed using a Superdex 200 column on an AKTA FPLC system (GE Healthcare). FC27 MSP2-6H fibrils (20 µM) were incubated with a 10-fold molar excess of EGCG for 1 week at 37°C on a rotator. A control sample of MSP2 fibrils was also analysed by size-exclusion chromatography. MSP2 fibrils were sonicated for 1 h in order to fragment them into shorter fibrils. The samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was loaded onto a Superdex 200 column. Proteins were eluted in PBS buffer at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The column was calibrated under similar conditions with thyroglobulin (670 kDa), bovine γ-globulin (156 kDa), ovalbumin (44 kDa), myoglobin (17 kDa) and vitamin B12 (1.35 kDa).

2.6. Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Far-UV CD spectra were collected on an Aviv 410SF CD spectrophotometer using a 1 mm path-length cell. CD spectra were recorded with a step size of 0.5 nm, a bandwidth of 1 nm and an averaging time of 2 s. MSP2 fibrils were buffer exchanged into 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 before CD measurements were performed. FC27 MSP2-6H fibril samples (5 µM) were incubated in the presence of equimolar and 10-fold molar excess of EGCG at 37 °C and CD spectra were recorded after 0, 1 and 24 h of incubation. EGCG contributes strongly to the far-UV CD spectra and the signal decreases upon incubation. Control solutions containing similar amounts of EGCG alone were incubated in parallel with protein samples containing EGCG. CD spectra were recorded for these EGCG solutions and subtracted from the corresponding protein spectra. Similarly, FC27 MSP2-6H samples (5 µM) were incubated in the presence of 15-fold molar excesses of baicalein and resveratrol and CD spectra were recorded after 0, 1 and 24 h of incubation. As DMSO contributes strongly to the far-UV CD spectrum, baicalein and resveratrol stocks used for CD studies were prepared in methanol, resulting in 0.4% methanol content in samples containing baicalein and resveratrol. CD spectra of the appropriate buffers and flavonoid solutions were recorded and subtracted from the corresponding protein spectra.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Flavonoids on Kinetics of Fibril Disaggregation

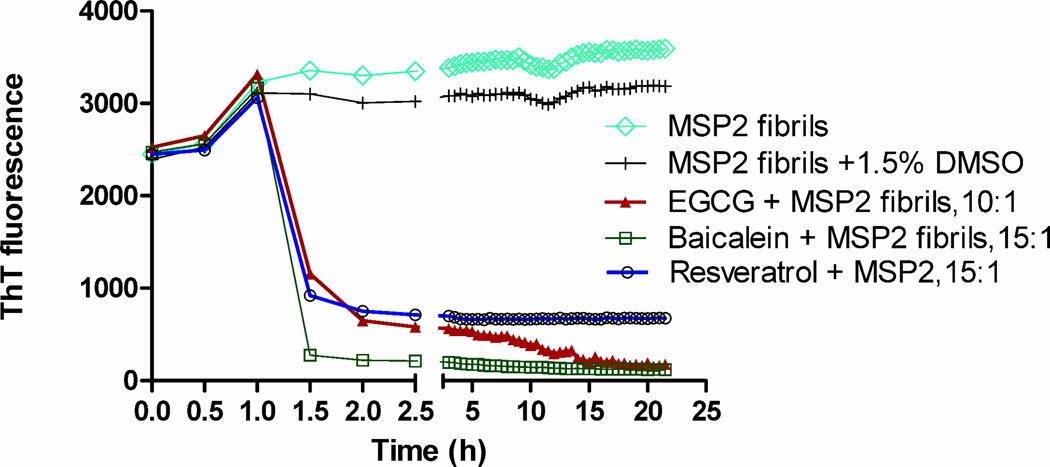

The effects of flavonoids on the kinetics of FC27 MSP2 fibril disaggregation were analysed initially using a ThT-binding assay. As shown previously, preformed MSP2 fibrils bind ThT efficiently in the absence of flavonoids, resulting in enhanced ThT fluorescence [4, 14]. ThT fluorescence decreased in a time-dependent manner upon incubation of MSP2 fibrils with EGCG (Fig. 1). This suggests a reduction in the fibril content of these samples compared with the control sample in which there was no significant reduction in ThT signal over time. Incubation of MSP2 fibrils with a 10-fold molar excess of EGCG reduced ThT fluorescence to approximately 30% after 1.5 h of incubation, after which the fluorescence decreased gradually over time to 5% after 21 h of incubation (Fig. 1). This decrease in ThT fluorescence was dose-dependent (Fig. S2), being evident even at stoichiometric concentrations of EGCG. When MSP2 fibrils were incubated with a 15-fold molar excess of baicalein there was a rapid, marked reduction in ThT fluorescence within 1.5 h of incubation (Fig. 1). Similarly, incubation of MSP2 fibrils with a 15-fold molar excess of resveratrol resulted in a rapid and significant loss of ThT fluorescence within 1.5 h of incubation but no further decay on further incubation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of flavonoids on ThT fluorescence of MSP2 fibrils. Kinetics was measured in the presence of EGCG, baicalein and resveratrol. FC27 MSP2-6H (40 µM) was incubated in the presence of a 10-fold molar excess of EGCG and a 15-fold molar excess each of baicalein and resveratrol, and ThT fluorescence was measured over a period of 22 h.

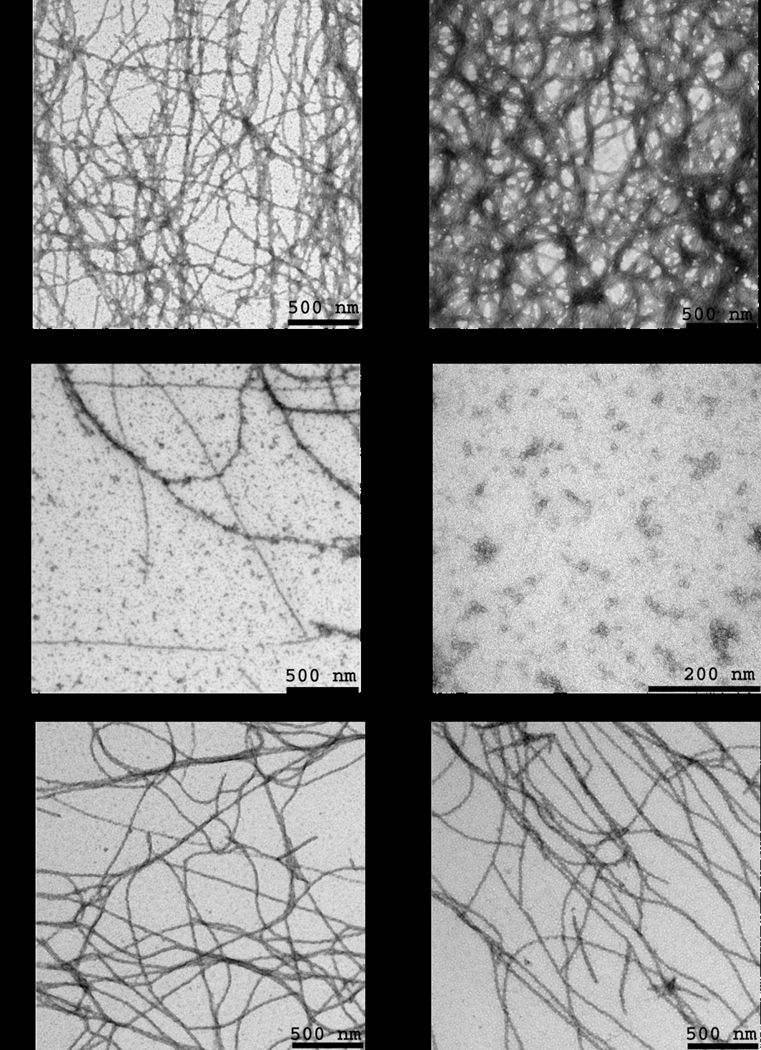

3.2. TEM Analysis of MSP2 Fibril Disaggregation

The effects of flavonoids on FC27 NT-MSP2 fibril morphology were characterized further by TEM. Negatively-stained samples of recombinant FC27 NT-MSP2 contained long fibrils of varying lengths (Fig. 2A). When FC27 NT-MSP2 fibrils were incubated with a 10-fold molar excess of EGCG very few fibrils were observed by TEM; instead, numerous compact aggregates were visible (Fig. 2C). These compact amorphous aggregates were made of smaller globular aggregates that range 10–20 nm in diameter (Fig. 2D). These results clearly indicate that MSP2 fibrils disassemble upon incubation with EGCG to produce much smaller aggregates.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of MSP2 fibril morphology by TEM after negative staining with 2% uranyl acetate. FC27 NT-MSP2 fibrils after incubation for 24 h in A) PBS, B) 1.5% DMSO, C & D) a 10-fold molar excess of EGCG, and a 15-fold molar excess of E) baicalein and F) resveratrol. D) Globular aggregates of MSP2 are components of the larger amorphous aggregates.

FC27 NT-MSP2 fibrils incubated with a 15-fold molar excess of baicalein or resveratrol contained an abundance of long fibrils (Fig. 2E & F). As the baicalein and resveratrol stock solutions were prepared in DMSO, a sample of MSP2 incubated with DMSO was examined by TEM and also found to contain numerous fibrils (Fig. 2B). From the TEM data it is impossible to exclude some effect of resveratrol and baicalein on the integrity of the MSP2 fibrils. However, these TEM observations are in contrast to the results of the ThT-binding assay, which showed marked reduction in ThT fluorescence intensity when MSP2 fibrils were incubated with baicalein and resveratrol (Fig. 1), and suggest that these flavonoids interfere with the ThT fluorescence assay.

3.3. Characterization of EGCG-Stabilized MSP2 Oligomers

In order to gain further insight into the oligomeric state of MSP2 in the presence of EGCG, size-exclusion chromatography was performed. Upon incubation with EGCG, MSP2 fibrils disassembled and eluted from the Superdex 200 column as a series of oligomers (Fig. S3). Long fibrils present in the untreated MSP2 sample were mostly removed in the sample preparation and fragmented shorter fibrils present in the sample eluted in the void volume.

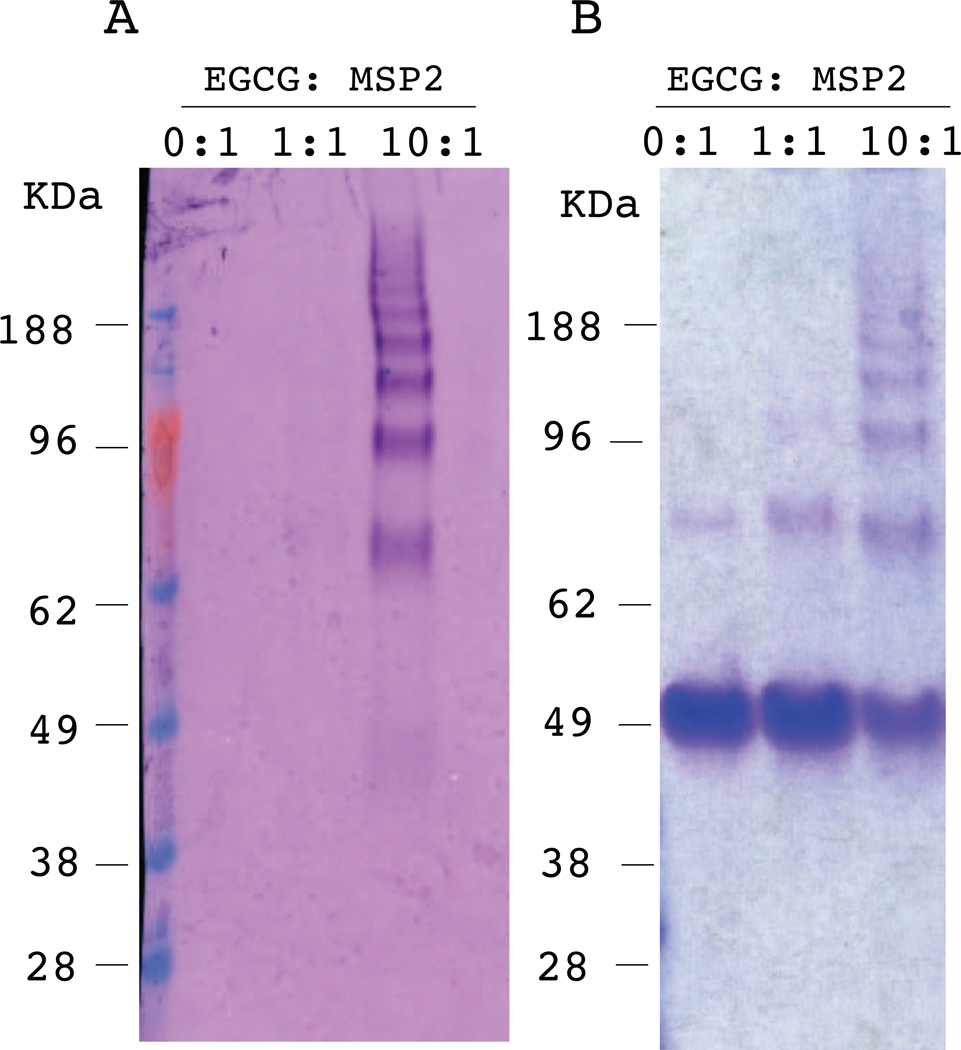

3.4. Detection of MSP2-bound EGCG Quinones

When incubated with EGCG, MSP2 fibrils form a series of oligomers, as confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 3B). These oligomers appear to be quite stable and do not disassemble in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Using a NBT staining assay, which detects protein-bound quinones [8, 18], we examined whether the alteration of fibrillar structure is initiated by direct binding of EGCG to MSP2 fibrils. FC27 NT-MSP2 fibrils were incubated in the absence and the presence of equimolar and a 10-fold excess of EGCG, and samples taken at various time intervals were analysed by NBT staining. NBT stained the MSP2 oligomers formed on disassembly of the fibrils, suggesting direct binding of EGCG to MSP2 (Fig. 3A). NBT staining was detectable for these samples only after 1 h of incubation with EGCG (Fig. S4) and no staining was observed for fibrils in the absence of EGCG.

Fig. 3.

EGCG binds directly to MSP2 fibrils. Comparison of A) Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT)-stained nitrocellulose membrane and B) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of MSP2 samples. FC27 NT-MSP2 was incubated for one week in the presence and absence of EGCG (molar ratios of EGCG to MSP2 are indicated above the gel).

To address the question of whether oxidation of EGCG was essential for MSP2 fibril disaggregation, MSP2 fibrils were incubated with EGCG in the presence of the antioxidant GSH. SDS-PAGE analysis of the samples indicated that MSP2 fibrils disassemble into a series of oligomers on incubation with EGCG even in the presence of GSH, indicating that oxidation of EGCG is not essential for its fibril-disaggregating activity (Fig. S5).

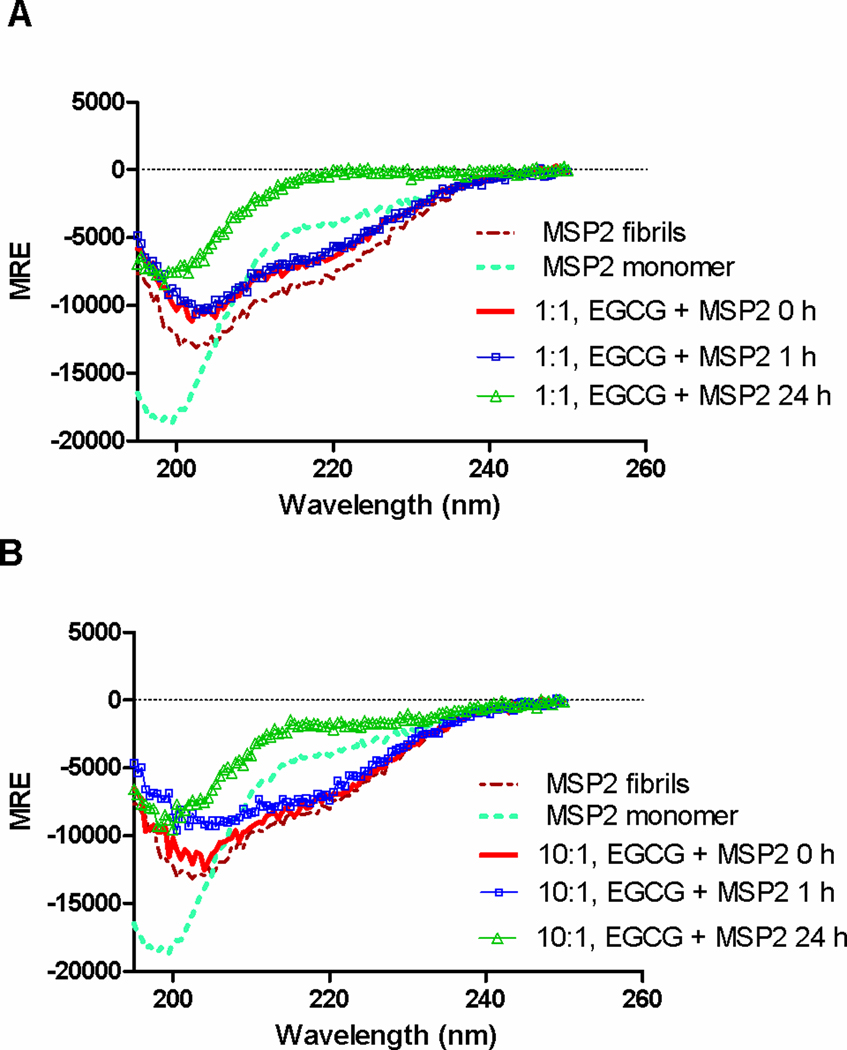

3.5. Effect of Flavonoids on the Secondary Structure of MSP2

Far-UV CD spectra of FC27 MSP2-6H fibrils were acquired in the absence and presence of flavonoids to study the effect of flavonoid binding on the β-sheet-rich structure of MSP2 fibrils. Previous studies have shown that MSP2 undergoes a conformational transition from random coil to β-sheet rich structure [4, 14] during polymerisation. FC27 MSP2-6H fibrils in PBS displayed CD spectra characteristic of a β-sheet rich structure (Fig. 4). There was no apparent change in the CD spectra of MSP2 fibrils immediately after addition of EGCG, but a loss of β-sheet structure of MSP2 fibrils was observed following incubation with EGCG for 24 h indicating that EGCG alters the β-sheet like structure of the fibril (Fig. 4). EGCG contributes strongly to the far-UV CD spectra, but the change in the CD spectra of MSP2 fibrils on addition of EGCG is not a subtraction artefact. The reduction in β-sheet content of EGCG-treated MSP2 fibril samples is consistent with the ThT and TEM data showing that EGCG disaggregates MSP2 fibrils. In contrast, FC27 MSP2-6H fibrils incubated in the presence of baicalein and resveratrol displayed CD spectra characteristic of a β-sheet rich structure similar to that of the control sample (Fig. S6), indicating that these flavonoids did not disaggregate MSP2 fibrils.

Fig. 4.

EGCG alters the structure of MSP2 fibrils. Far-UV CD spectra of FC27 MSP2-6H were measured in the absence and presence of A) equimolar and B) 10-fold excesses of EGCG. CD spectra were recorded for the samples after incubation with EGCG for 0, 1 and 24 h.

4. Discussion

Flavonoids constitute one of the most potent classes of anti-aggregation agents. Recent studies have demonstrated that EGCG, baicalein and resveratrol exhibit potent antiamyloidogenic activity and that these flavonoids efficiently modulate amyloid fibril assembly by several natively unstructured proteins [8, 9]. In a recent study, we tested the ability of EGCG, baicalein and resveratrol to inhibit MSP2 fibrillogenesis and found marked inhibition with EGCG [14]. We have therefore investigated the ability of EGCG, baicalein and resveratrol to disaggregate MSP2 fibrils.

Data from ThT-binding assays, TEM and CD studies indicate that EGCG disaggregates MSP2 fibrils. We found that EGCG binds to preformed MSP2 fibrils and remodels their structure to form smaller oligomeric aggregates. A significant reduction of ThT fluorescence was observed on incubation of MSP2 fibrils with EGCG for 1 h, suggesting that EGCG-mediated remodelling is detectable after a short time. However, significant changes in MSP2 fibril structure could be detected by CD spectroscopy only after 24 h of incubation with EGCG. The CD data indicated that EGCG-treated MSP2 fibrils disaggregate into predominantly unstructured MSP2 oligomers. Even though ThT fluorescence was also reduced in the presence of baicalein and resveratrol, TEM and CD data indicated that baicalein and resveratrol-treated MSP2 samples contained significant quantities of fibrils, suggesting that baicalein and resveratrol interfere with the ThT fluorescence assay but do not alter the fibril content. Consistent with this, a recent study has shown that resveratrol can significantly bias the ThT fluorescence assay by competitively inhibiting the binding of ThT to fibrils [19].

SDS-PAGE analyses and NBT staining indicate that EGCG binds to preformed MSP2 fibrils directly and alters their morphology in vitro. EGCG disassembles MSP2 fibrils into amorphous, soluble oligomers, but the mechanism by which this occurs is yet to be determined. It has been suggested [15] that EGCG-mediated reorientation of bonds between ordered protein molecules in the amyloid fibril might be responsible for fibril remodelling and the appearance of unordered, amorphous protein aggregates. We have shown in this study that EGCG-quinones bind to MSP2 fibrils (Fig. 3) and the stability of this interaction implies chemical modification of MSP2 by EGCG.

In conclusion, EGCG appears to be a potent modulator of fibril formation and aids in dissolution of pre-formed MSP2 fibrils. The probable chemical modification of MSP2 by EGCG would most likely not be acceptable, from a regulatory perspective, in a vaccine formulation. Further studies are therefore necessary to elucidate the nature of this interaction and to examine in detail the immunogenicity of the soluble oligomers generated by EGCG-mediated disassembly of MSP2 fibrils. EGCG, being a potent modulator of fibril assembly, is nonetheless a useful mechanistic probe to study MSP2 oligomerization and the formation of amyloid-like fibrils by this protein.

Research Highlights.

-

➢

Merozoite surface protein 2 (MSP2), a malaria surface antigen, forms amyloid-like fibrils in solution.

-

➢

EGCG disaggregates pre-formed MSP2 fibrils into soluble oligomers.

-

➢

EGCG remodels MSP2 fibrils by altering the β-sheet-like structure of the fibrils.

-

➢

Other flavonoids, such as baicalein and resveratrol, do not disaggregate MSP2 fibrils.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants to R.F.A. and R.S.N. from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Project grant 637368) and the National Institutes of Health (grant R01AI59229). R.S.N. acknowledges fellowship support from the NHMRC.

We thank Dr Jeff Babon for helpful discussions. We thank Dr Matthew Perugini and members of his lab at the Bio21 Institute, University of Melbourne, for access to their CD spectrometer.

Abbreviations

- CD

circular dichroism

- EGCG

epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- FC27 MSP2-6H

C-terminally His-tagged full-length FC27 MSP2

- FC27 NT-MSP2

untagged full-length FC27 MSP2

- GPI

glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- MSP2

merozoite surface protein 2

- NBT

Nitroblue tetrazolium

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- ThT

Thioflavin T

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smythe JA, Coppel RL, Brown GV, Ramasamy R, Kemp DJ, Anders RF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:5195–5199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerold P, Schofield L, Blackman MJ, Holder AA, Schwarz RT. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1996;75:131–143. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genton B, Betuela I, Felger I, Al-Yaman F, Anders RF, Saul A, Rare L, Baisor M, Lorry K, Brown GV, Pye D, Irving DO, Smith TA, Beck HP, Alpers MP. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;185:820–827. doi: 10.1086/339342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adda CG, Murphy VJ, Sunde M, Waddington LJ, Schloegel J, Talbo GH, Vingas K, Kienzle V, Masciantonio R, Howlett GJ, Hodder AN, Foley M, Anders RF. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2009;166:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Perugini MA, Yao S, Adda CG, Murphy VJ, Low A, Anders RF, Norton RS. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;379:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low A, Chandrashekaran IR, Adda CG, Yao S, Sabo JK, Zhang X, Soetopo A, Anders RF, Norton RS. Biopolymers. 2007;87:12–22. doi: 10.1002/bip.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X, Adda CG, Keizer DW, Murphy VJ, Rizkalla MM, Perugini MA, Jackson DC, Anders RF, Norton RS. J. Pept. Sci. 2007;13:839–848. doi: 10.1002/psc.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrnhoefer DE, Bieschke J, Boeddrich A, Herbst M, Masino L, Lurz R, Engemann S, Pastore A, Wanker EE. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:558–566. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu M, Rajamani S, Kaylor J, Han S, Zhou F, Fink AL. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:26846–26857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403129200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong DP, Fink AL, Uversky VN. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;383:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandel SA, Amit T, Weinreb O, Reznichenko L, Youdim MB. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2008;14:352–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson SA, Ecroyd H, Dehle FC, Musgrave IF, Carver JA. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;392:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehrnhoefer DE, Duennwald M, Markovic P, Wacker JL, Engemann S, Roark M, Legleiter J, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Lindquist S, Muchowski PJ, Wanker EE. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:2743–2751. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandrashekaran IR, Adda CG, MacRaild CA, Anders RF, Norton RS. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5899–5908. doi: 10.1021/bi902197x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bieschke J, Russ J, Friedrich RP, Ehrnhoefer DE, Wobst H, Neugebauer K, Wanker EE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7710–7715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910723107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng F, Abedini A, Plesner A, Verchere CB, Raleigh DP. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8127–8133. doi: 10.1021/bi100939a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeVine H., 3rd Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:274–284. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paz MA, Fluckiger R, Boak A, Kagan HM, Gallop PM. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudson SA, Ecroyd H, Kee TW, Carver JA. FEBS J. 2009;276:5960–5972. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.