Abstract

JAK2V617F is sufficiently prevalent in BCR-ABL1-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) to be useful as a clonal marker. JAK2V617F mutation screening is indicated for the evaluation of erythrocytosis, thrombocytosis, splanchnic vein thrombosis, and otherwise unexplained BCR-ABL1-negative granulocytosis. However, the mutation does not provide additional value in the presence of unequivocal morphologic diagnosis, and its presence does not necessarily distinguish one MPN from another or provide useful prognostic information. In general, quantitative cell-based JAK2V617F mutation assays are preferred because the additional information obtained on mutant allele burden enhances diagnostic certainty and facilitates monitoring of response to treatment. JAK2 exon 12 mutation screening is indicated only in the presence of JAK2V617F-negative erythrocytosis that is associated with a subnormal serum erythropoietin level. MPL mutations are neither frequent nor specific enough to warrant their routine use for MPN diagnosis, but they may be useful in resolving specific diagnostic problems. The practice of en bloc screening for JAK2V617F, JAK2 exon 12, and MPL mutations is scientifically irrational and economically irresponsible.

Morphology is the cornerstone of current diagnosis and classification in myeloid malignancies.1 Cytochemical, immunophenotypic, cytogenetic, and molecular data enhance diagnostic accuracy and form the basis for the World Health Organization classification of myeloid malignancies into five main categories2: acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs), myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), MDS/MPN overlap, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor gene or fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 gene rearranged myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms associated with eosinophilia. The World Health Organization MPN category includes eight subcategories: chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), primary myelofibrosis (PMF), mastocytosis, chronic eosinophilic leukemia not otherwise specified, chronic neutrophilic leukemia, and MPN unclassifiable.1 Among these subcategories, the first four (ie, chronic myelogenous leukemia, PV, ET, and PMF) are currently referred to as “classic” MPNs, because they were included in the original description of myeloproliferative disorders by William Dameshek.3 In general, current evidence supports consideration of all myeloid malignancies, including MPN, as clonal stem cell diseases.

JAK2 and MPL mutations occur across the spectrum of myeloid malignancies, including MPN, MDS, MDS/MPN, and acute myeloid leukemia (Table 1).4–7 These mutations are most prevalent in the BCR-ABL1-negative classic MPN (ie, PV, ET, and PMF), which are morphologically characterized by the absence of both cellular dysplasia and monocytosis and the presence of abnormal megakaryocytes that are increased in number and often found in clusters. Megakaryocyte morphology and degree of trilineage proliferation differ among the three BCR-ABL1-negative classic MPNs. Megakaryocytes are large, hyperlobulated, and mature appearing in ET8; immature appearing with hyperchromatic and irregularly folded bulky nuclei in PMF8; and pleomorphic without maturation defects in PV.9,10 Megakaryocyte changes in BCR-ABL1-negative MPN are accompanied by left-shifted granulocyte proliferation in PMF, trilineage proliferation in PV, and otherwise normal-appearing bone marrow in ET. Overt bone marrow fibrosis is absent in prefibrotic PMF, which is otherwise characterized by the aforementioned PMF-associated changes in megakaryocyte morphology and increased granulocyte proliferation.11 Controversy is ongoing about the utility of morphology alone to distinguish ET from early PMF12; however, this is irrelevant because clinical pathologists never base their diagnostic impressions on morphology alone, and they also consider clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular information.1,11

Table 1.

Currently Known Mutations in BCR-ABL1-Negative Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

| Mutations | Chromosome location | Mutational frequency, % |

|---|---|---|

| JAK2 | 9p24 | |

| PV | ∼964 | |

| ET | ∼554 | |

| PMF | ∼654 | |

| BP-MPN | ∼504 | |

| JAK2 exon 12 mutation [4] | 9p24 | |

| PV | ∼34 | |

| MPL | 1p34 | |

| ET | ∼34 | |

| PMF | ∼104 | |

| BP-MPN | ∼54 | |

| LNK | 12q24.12 | |

| PV | Rare20,21 | |

| ET | Rare19,20 | |

| PMF | Rare19,20 | |

| BP-MPN | ∼1020 | |

| TET2 | 4q24 | |

| PV | ∼164 | |

| ET | ∼54 | |

| PMF | ∼174 | |

| BP-MPN | ∼174 | |

| ASXL1 | 20q11.1 | |

| ET | ∼332 | |

| PMF | ∼13 | |

| BP-MPN | ∼18 | |

| IDH1/IDH2 | 2q33.3/15q26.1 | |

| PV | ∼224 | |

| ET | ∼124 | |

| PMF | ∼424 | |

| BP-MPN | ∼2024 | |

| EZH2 | 7q36.1 | |

| PV | ∼334 | |

| PMF | ∼7 | |

| DNMT3A | 2p23 | |

| PV | ∼735 | |

| PMF | ∼735,36 | |

| BP-MPN | ∼1435,36 | |

| CBL | 11q23.3 | |

| PV | Rare22 | |

| ET | Rare22 | |

| MF | ∼622 | |

| IKZF1 | 7p12 | |

| CP-MPN | Rare27 | |

| BP-MPN | ∼1927 |

BP-MPN, blast-phase MPN; CP-MPN, chronic phase MPN; MF, both PMF and post-ET/PV myelofibrosis.

Clinically, PV and ET are characterized by erythrocytosis and thrombocytosis, respectively, and leukocytosis, splenomegaly, thrombohemorrhagic complications, vasomotor disturbances, pruritus, and a small risk of disease progression into acute leukemia or myelofibrosis.13 PMF is characterized by anemia, splenomegaly, extramedullary hematopoiesis, constitutional symptoms, and a higher risk of leukemic progression.14 Median survival exceeds 15 years in both ET and PV, but it is significantly shorter in PMF. The goal of therapy in PV and ET is to prevent thrombotic complications. Low-dose aspirin is the cornerstone of therapy in both PV and ET.15 In addition, phlebotomy is required in PV and hydroxyurea therapy in high-risk disease (history of thrombosis or age >60 years).13 PMF is managed according to risk category from the Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System.16 Patients with low-risk or intermediate-1 PMF are managed by observation alone or conventional drug therapy, whereas allogeneic stem cell transplantation or experimental drug therapy might be necessary for intermediate-2 or high-risk disease.

Overview of Mutations Associated with BCR-ABL1-Negative MPNs

The disease-initiating mutation(s) in BCR-ABL1-negative MPN is unknown. However, JAK2V617F is present in most patients with PV, ET, or PMF, and a minority of patients with these diseases also harbor JAK2 exon 12, MPL, LNK, CBL, TET2, ASXL1, IDH, IKZF1, EZH2, or DNMT3A mutations (Table 1).4 These mutations are currently thought to represent secondary events and to lack both disease specificity and mutual exclusivity. Some patients carry more than one mutation, and clonal hierarchy in such instances appears to be unpredictable.17

JAK2 (Janus kinase 2) maps to chromosome 9p24. JAK2V617F is located on exon 14 and occurs in ∼96% of patients with PV, 55% with ET, and 65% with PMF.4 JAK2V617F contributes to abnormal myeloproliferation in MPN, whereas such effect is erythroid lineage weighted with JAK2 exon 12 mutation.4 MPL (myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene) maps to chromosome 1p34, and MPL mutations usually involve exon 10 and contribute to primarily megakaryocytic myeloproliferation.4 MPL mutational frequencies are estimated at 3% in ET and 10% in PMF.4 LNK (as in Links) maps to chromosome 12q24.12 and encodes for a membrane-bound adaptor protein that negatively regulates JAK2 signaling.18 LNK mutations usually involve exon 2, are inactivating, and occur in ∼10% of patients with blast-phase MPN, whereas they are infrequent in chronic-phase disease.19–21

CBL (Casitas B-lineage lymphoma proto-oncogene) maps to chromosome 11q23.3, and its mutations involve exons 8 and 9.22 CBL is an E3-ubiquitin ligase that marks mutant kinases for degradation.23 CBL mutations are rare in PV and ET but are reported to occur in ∼6% of patients in myelofibrosis.22 IDH1 and IDH2 (isocitrate dehydrogenase) map to chromosomes 2q33.3 and 15q26.1, respectively, and their mutations involve exon 4.24 IDH mutations induce formation of 2-hydroxyglutarate, which is thought to be oncogenic.25 IDH mutational frequencies are estimated at 2% in PV, 1% in ET, 4% in PMF, and 20% in blast-phase MPN.24 IKAROS family zinc finger 1 (IKZF1) maps to chromosome 7p12 and is thought to function as a transcription regulator and tumor suppressor.26 IKZF1 mutations are rare in chronic-phase MPN but might be detected in ∼19% of patients with blast-phase MPN.27

TET oncogene family member 2 (TET2) maps to chromosome 4q24. TET2 mutations occur across several of the gene's 12 exons.4 TET proteins catalyze conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine,28,29 and, accordingly, TET2 mutations are thought to contribute to epigenetic dysregulation of transcription. TET2 mutational frequencies are estimated at 16% in PV, 5% in ET, 17% in PMF, and 17% in blast-phase MPN.4 Additional sex combs-like 1 (ASXL1) maps to chromosome 20q11.1, and ASXL1 mutations involve exon 12. Wild-type ASXL1 is needed for normal hematopoiesis30 and might be involved in transcriptional repression.31 ASXL1 mutations are rare in PV or ET32 but were reported at ∼13% in PMF and 18% in blast-phase MPN.33 Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) maps to chromosome 7q36.1, and EZH2 mutations involve exons 10, 18, and 20.34 Wild-type EZH2 is part of a histone methyltransferase and might function both as a tumor suppressor and an oncogene.34 EZH2 mutational frequencies are reported at ∼3% in PV34 and 7% in PMF.33

Most recently, DNA methyltransferase 3a (DNMT3A) mutations were reported in patients with acute myeloid leukemia, MDS, and MPN; mutational frequencies in the latter were reported at ∼7% for PV, 6% for PMF, and 14% for blast-phase MPN.35 Another study of 46 patients with PMF, 22 with post-ET/PV myelofibrosis, and 11 with blast-phase MPN reported corresponding DNMT3A mutational frequencies of 7%, 0%, and 0%, respectively.36 All 13 DNMT3A mutations reported in those two studies were heterozygous, and the most frequent mutations affected amino acid R882. DNMT3A mutations in those two MPN studies were documented to occur in the presence or absence of JAK2, IDH, ASXL1, or TET2 mutations.

In summary, activating JAK2 and MPL mutations and LNK loss-of-function result in constitutive JAK-STAT activation and induce MPN-like disease in mice.19,37–39 TET2, ASXL1, and EZH2 mutations might contribute to epigenetic dysregulation of transcription.28,29,31

JAK2 and MPL Mutation Screening in Routine Clinical Practice

The decision to screen for JAK2 or MPL mutations, in the context of routine clinical practice, is based on a number of facts and possibilities:

-

•

JAK2V617F is present in most patients with PV, ET, or PMF but lacks disease specificity or prognostic value.40

-

•

JAK2V617F also occurs in other myeloid malignancies and is therefore useful as a clonal marker in the evaluation of otherwise unexplained BCR-ABL1-negative granulocytosis or monocytosis.41

-

•

JAK2V617F, but not JAK2 exon 12 or MPL mutations,42 has been shown to identify occult MPN in patients with splanchnic vein thrombosis,43 but the yield of mutation screening in the evaluation of non-splanchnic thrombosis is very low.44,45

-

•

JAK2 mutations are present in virtually all patients with PV; therefore their screening is reasonable in the presence of characteristic symptoms of PV such as aquagenic pruritus or unexplained splenomegaly, even if the complete blood count picture is not suggestive of PV.46

-

•

JAK2V617F studies are concordant between peripheral blood and bone marrow; therefore, patients may be screened with either specimen type, but analyzing both blood and marrow is unnecessary.47,48

-

•

JAK2 exon 12 mutations are rare in ET or PMF, and their occurrence in PV is almost always associated with the absence of JAK2V617F and the presence of a subnormal serum erythropoietin level.46,49

-

•

The incidence of MPL mutations in MPN are too low (see above) to warrant their routine use in MPN diagnosis, except for clarification of equivocal morphology in the diagnosis of ET or PMF.7

-

•

JAK2 and MPL mutations do not occur in healthy subjects or in those with non-clonal causes of myeloproliferation.7,50,51

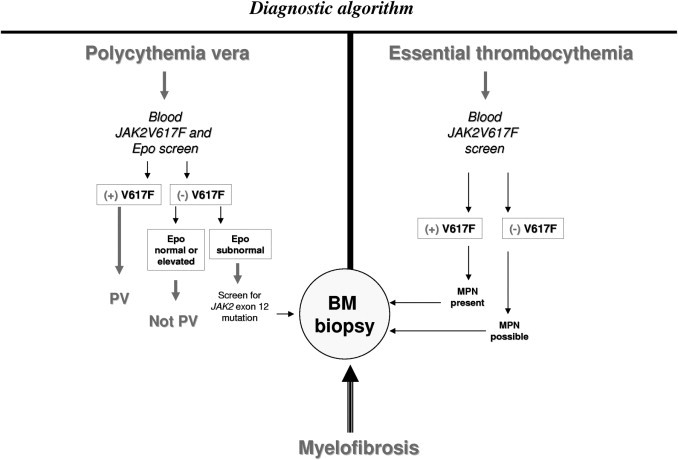

Taking the above-mentioned factors into consideration, we have outlined the clinical scenarios in which JAK2 or MPL mutations are indicated (Table 2) and also provided a diagnostic algorithm for PV, ET, and PMF (Figure 1). At present, it is not essential to use quantitative assays for mutation screening, although we prefer to use cell-based quantitative assays because diagnosis certainty is enhanced in the presence of >1% mutant allele burden.50 In addition, a ≥50% JAK2V617F allele burden suggests the presence of homozygous mutations, which are atypical for ET,40,52 but a lower mutant allele burden does not necessarily exclude the presence of homozygously mutated cells and is, therefore, of limited value in distinguishing ET from PV or PMF. Cell-based quantitative assays are also useful to monitor treatment response, including assessment of minimal residual disease after allogenic stem cell transplantation.53–56

Table 2.

Clinical Indications for Screening JAK2 and MPL Mutations

| Mutation | Screening appropriate | Not indicated |

|---|---|---|

| JAK2V617F | Erythrocytosis | For purposes of MPN prognostication |

| Thrombocytosis | To differentiate one MPN from another | |

| Bone marrow fibrosis | Testing both blood and bone marrow | |

| BCR-ABL1-negative granulocytosis | ||

| Unexplained monocytosis | ||

| Unexplained splenomegaly | ||

| Aquagenic pruritus | ||

| Splanchnic vein thrombosis | ||

| Testing either blood or bone marrow | ||

| JAK2 exon 12 mutation | JAK2V617F-negative erythrocytosis and low Epo | Before JAK2V617F screening |

| Suspected JAK2V617F-negative post-PV MF | In the presence of JAK2V617F | |

| For diagnosis of ET or PMF | ||

| MPL mutation | Thrombocytosis and morphologically equivocal for ET | For diagnosis of PV Morphologically confirmed ET or PMF |

| Marrow fibrosis and morphologically equivocal for PMF | JAK2V617F positive |

Epo, serum erythropoietin level; MF, myelofibrosis.

Figure 1.

A contemporary diagnostic algorithm for MPNs, including PV, ET, and PMF. Epo, erythropoietin; V617F, JAK2V617F; BM, bone marrow.

Recent studies in PV have suggested the association of higher mutant allele burden with a higher risk of fibrotic transformation57 and in PMF a lower mutant allele burden with inferior survival.58,59 However, the lack of assay standardization across different laboratories undermines the practical translation of such observations, at present. In general, mutation screening outcome does not appear to be influenced by or whether peripheral blood or bone marrow is used as the source of test samples.47 Finally, it is important to note that most commercial assays use ≥1% sensitivity level to minimize false-positive test results; however, positive signals in the 0.01% to 1% range should not be discarded, especially in the context of the appropriate clinical scenario.

Footnotes

CME Disclosure: None of the authors disclosed any relevant financial relationships.

References

- 1.Vardiman J.W., Thiele J., Arber D.A., Brunning R.D., Borowitz M.J., Porwit A., Harris N.L., Le Beau M.M., Hellstrom-Lindberg E., Tefferi A., Bloomfield C.D. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow SH Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H., Thiele J., Vardiman J.W. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2008. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tefferi A. The history of myeloproliferative disorders: before and after Dameshek. Leukemia. 2008;22:3–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tefferi A. Novel mutations and their functional and clinical relevance in myeloproliferative neoplasms: JAK2, MPL, TET2, ASXL1, CBL, IDH and IKZF1. Leukemia. 2010;24:1128–1138. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patnaik M.M., Lasho T.L., Finke C.M., Gangat N., Caramazza D., Holtan S.G., Pardanani A., Knudson R.A., Ketterling R.P., Chen D., Hoyer J.D., Hanson C.A., Tefferi A. WHO-defined ‘myelodysplastic syndrome with isolated del(5q)’ in 88 consecutive patients: survival data, leukemic transformation rates and prevalence of JAK2: MPL and IDH mutations. Leukemia. 2010;24:1283–1289. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szpurka H., Tiu R., Murugesan G., Aboudola S., Hsi E.D., Theil K.S., Sekeres M.A., Maciejewski J.P. Refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts associated with marked thrombocytosis (RARS-T), another myeloproliferative condition characterized by JAK2 V617F mutation. Blood. 2006;108:2173–2181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pardanani A.D., Levine R.L., Lasho T., Pikman Y., Mesa R.A., Wadleigh M., Steensma D.P., Elliott M.A., Wolanskyj A.P., Hogan W.J., McClure R.F., Litzow M.R., Gilliland D.G., Tefferi A. MPL515 mutations in myeloproliferative and other myeloid disorders: a study of 1182 patients. Blood. 2006;108:3472–3476. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tefferi A., Skoda R., Vardiman J.W. Myeloproliferative neoplasms: contemporary diagnosis using histology and genetics. Nature Rev. 2009;6:627–637. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kvasnicka H.M., Thiele J. Prodromal myeloproliferative neoplasms: the 2008 WHO classification. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:62–69. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thiele J., Kvasnicka H.M., Vardiman J. Bone marrow histopathology in the diagnosis of chronic myeloproliferative disorders: a forgotten pearl. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2006;19:413–437. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thiele J., Kvasnicka H.M., Vardiman J.W., Orazi A., Franco V., Gisslinger H., Birgegard G., Griesshammer M., Tefferi A. Bone marrow fibrosis and diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia (letter to the editor) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:e220–e221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3485. author reply e222-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkins B.S., Erber W.N., Bareford D., Buck G., Wheatley K., East C.L., Paul B., Harrison C.N., Green A.R., Campbell P.J. Bone marrow pathology in essential thrombocythemia: interobserver reliability and utility for identifying disease subtypes. Blood. 2008;111:60–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tefferi A. Essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis: current management and the prospect of targeted therapy. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:491–497. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tefferi A. Myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1255–1265. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landolfi R., Marchioli R., Kutti J., Gisslinger H., Tognoni G., Patrono C., Barbui T. Efficacy and safety of low-dose aspirin in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:114–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gangat N., Caramazza D., Vaidya R., George G., Begna K.H., Schwager S.M., Van Dyke D.L., Hanson C.A., Wu W., Pardanani A., Cervantes F., Passamonti F., Tefferi A. DIPSS-Plus: a refined Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System (DIPSS) for primary myelofibrosis that incorporates prognostic information from karyotype, platelet count and transfusion status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:392–397. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaub F.X., Looser R., Li S., Hao-Shen H., Lehmann T., Tichelli A., Skoda R.C. Clonal analysis of TET2 and JAK2 mutations suggests that TET2 can be a late event in the progression of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;115:2003–2007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gery S., Cao Q., Gueller S., Xing H., Tefferi A., Koeffler H.P. Lnk inhibits myeloproliferative disorder-associated JAK2 mutant. JAK2V617F. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:957–965. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0908575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh S.T., Simonds E.F., Jones C., Hale M.B., Goltsev Y., Gibbs K.D., Jr, Merker J.D., Zehnder J.L., Nolan G.P., Gotlib J. Novel mutations in the inhibitory adaptor protein LNK drive JAK-STAT signaling in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;116:988–992. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardanani A., Lasho T., Finke C., Oh S.T., Gotlib J., Tefferi A. LNK mutation studies in blast-phase myeloproliferative neoplasms, and in chronic-phase disease with TET2: IDH, JAK2 or MPL mutations. Leukemia. 2010;24:1713–1718. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasho T.L., Pardanani A., Tefferi A. LNK mutations in JAK2 mutation-negative erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1189–1190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1006966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grand F.H., Hidalgo-Curtis C.E., Ernst T., Zoi K., Zoi C., McGuire C., Kreil S., Jones A., Score J., Metzgeroth G., Oscier D., Hall A., Brandts C., Serve H., Reiter A., Chase A.J., Cross N.C. Frequent CBL mutations associated with 11q acquired uniparental disomy in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2009;113:6182–6192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanada M., Suzuki T., Shih L.Y., Otsu M., Kato M., Yamazaki S., Tamura A., Honda H., Sakata-Yanagimoto M., Kumano K., Oda H., Yamagata T., Takita J., Gotoh N., Nakazaki K., Kawamata N., Onodera M., Nobuyoshi M., Hayashi Y., Harada H., Kurokawa M., Chiba S., Mori H., Ozawa K., Omine M., Hirai H., Nakauchi H., Koeffler H.P., Ogawa S. Gain-of-function of mutated C-CBL tumour suppressor in myeloid neoplasms. Nature. 2009;460:904–908. doi: 10.1038/nature08240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tefferi A., Lasho T.L., Abdel-Wahab O., Guglielmelli P., Patel J., Caramazza D., Pieri L., Finke C.M., Kilpivaara O., Wadleigh M., Mai M., McClure R.F., Gilliland D.G., Levine R.L., Pardanani A., Vannucchi A.M. IDH1 and IDH2 mutation studies in 1473 patients with chronic-, fibrotic- or blast-phase essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera or myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2010;24:1302–1309. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward P.S., Patel J., Wise D.R., Abdel-Wahab O., Bennett B.D., Coller H.A., Cross J.R., Fantin V.R., Hedvat C.V., Perl A.E., Rabinowitz J.D., Carroll M., Su S.M., Sharp K.A., Levine R.L., Thompson C.B. The common feature of leukemia-associated IDH1 and IDH2 mutations is a neomorphic enzyme activity converting alpha-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trageser D., Iacobucci I., Nahar R., Duy C., von Levetzow G., Klemm L., Park E., Schuh W., Gruber T., Herzog S., Kim Y.M., Hofmann W.K., Li A., Storlazzi C.T., Jack H.M., Groffen J., Martinelli G., Heisterkamp N., Jumaa H., Muschen M. Pre-B cell receptor-mediated cell cycle arrest in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia requires IKAROS function. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1739–1753. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jager R., Gisslinger H., Passamonti F., Rumi E., Berg T., Gisslinger B., Pietra D., Harutyunyan A., Klampfl T., Olcaydu D., Cazzola M., Kralovics R. Deletions of the transcription factor Ikaros in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2010;24:1290–1298. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tahiliani M., Koh K.P., Shen Y., Pastor W.A., Bandukwala H., Brudno Y., Agarwal S., Iyer L.M., Liu D.R., Aravind L., Rao A. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ko M., Huang Y., Jankowska A.M., Pape U.J., Tahiliani M., Bandukwala H.S., An J., Lamperti E.D., Koh K.P., Ganetzky R., Liu X.S., Aravind L., Agarwal S., Maciejewski J.P., Rao A. Impaired hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine in myeloid cancers with mutant TET2. Nature. 2010;468:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature09586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher C.L., Pineault N., Brookes C., Helgason C.D., Ohta H., Bodner C., Hess J.L., Humphries R.K., Brock H.W. Loss-of-function Additional sex combs like 1 mutations disrupt hematopoiesis but do not cause severe myelodysplasia or leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:38–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-230698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S.W., Cho Y.S., Na J.M., Park U.H., Kang M., Kim E.J., Um S.J. ASXL1 represses retinoic acid receptor-mediated transcription through associating with HP1 and LSD1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Carbuccia N., Murati A., Trouplin V., Brecqueville M., Adelaide J., Rey J., Vainchenker W., Bernard O.A., Chaffanet M., Vey N., Birnbaum D., Mozziconacci M.J. Mutations of ASXL1 gene in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2009;23:2183–2186. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdel-Wahab O., Pardanani A., Patel J., Lasho T., Heguy A., Levine R., Tefferi A. Concomitant analysis of EZH2 and ASXL1 mutations in myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and blast-phase myeloproliferative neoplasms (abstract) Blood. 2010;116:3070. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ernst T., Chase A.J., Score J., Hidalgo-Curtis C.E., Bryant C., Jones A.V., Waghorn K., Zoi K., Ross F.M., Reiter A., Hochhaus A., Drexler H.G., Duncombe A., Cervantes F., Oscier D., Boultwood J., Grand F.H., Cross N.C. Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat Genet. 2010;42:722–726. doi: 10.1038/ng.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stegelmann F., Bullinger L., Schlenk R.F., Paschka P., Griesshammer M., Blersch C., Kuhn S., Schauer S., Dohner H., Dohner K. DNMT3A mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2001 doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.77. [Epub ahead of press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdel-Wahab O., Pardanani A., Rampal R., Lasho T.L., Levine R.L., Tefferi A. DNMT3A mutational analysis in primary myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and advanced phases of myeloproliferative neoplasms (letter to the editor) Leukemia. 2011;25:1219–1220. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James C., Ugo V., Le Couedic J.P., Staerk J., Delhommeau F., Lacout C., Garcon L., Raslova H., Berger R., Bennaceur-Griscelli A., Villeval J.L., Constantinescu S.N., Casadevall N., Vainchenker W. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434:1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pikman Y., Lee B.H., Mercher T., McDowell E., Ebert B.L., Gozo M., Cuker A., Wernig G., Moore S., Galinsky I., Deangelo D.J., Clark J.J., Lee S.J., Golub T.R., Wadleigh M., Gilliland D.G., Levine R.L. MPLW515L is a novel somatic activating mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bersenev A., Wu C., Balcerek J., Jing J., Kundu M., Blobel G.A., Chikwava K.R., Tong W. Lnk constrains myeloproliferative diseases in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2058–2069. doi: 10.1172/JCI42032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vannucchi A.M., Antonioli E., Guglielmelli P., Pardanani A., Tefferi A. Clinical correlates of JAK2V617F presence or allele burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms: a critical reappraisal. Leukemia. 2008;22:1299–1307. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steensma D.P., Dewald G.W., Lasho T.L., Powell H.L., McClure R.F., Levine R.L., Gilliland D.G., Tefferi A. The JAK2 V617F activating tyrosine kinase mutation is an infrequent event in both “atypical” myeloproliferative disorders and myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2005;106:1207–1209. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiladjian J.J., Cervantes F., Leebeek F.W., Marzac C., Cassinat B., Chevret S., Cazals-Hatem D., Plessier A., Garcia-Pagan J.C., Murad S.D., Raffa S., Janssen H.L., Gardin C., Cereja S., Tonetti C., Giraudier S., Condat B., Casadevall N., Fenaux P., Valla D.C. The impact of JAK2 and MPL mutations on diagnosis and prognosis of splanchnic vein thrombosis: a report on 241 cases. Blood. 2008;111:4922–4929. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-125328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dentali F., Squizzato A., Brivio L., Appio L., Campiotti L., Crowther M., Grandi A.M., Ageno W. JAK2V617F mutation for the early diagnosis of Ph- myeloproliferative neoplasms in patients with venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Blood. 2009;113:5617–5623. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pardanani A., Lasho T.L., Hussein K., Schwager S.M., Finke C.M., Pruthi R.K., Tefferi A. JAK2V617F mutation screening as part of the hypercoagulable work-up in the absence of splanchnic venous thrombosis or overt myeloproliferative neoplasm: assessment of value in a series of 664 consecutive patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:457–459. doi: 10.4065/83.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pardanani A., Lasho T.L., Schwager S., Finke C., Hussein K., Pruthi R.K., Tefferi A. JAK2V617F prevalence and allele burden in non-splanchnic venous thrombosis in the absence of overt myeloproliferative disorder (letter to the editor) Leukemia. 2007;21:1828–1829. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pardanani A., Lasho T.L., Finke C., Hanson C.A., Tefferi A. Prevalence and clinicopathologic correlates of JAK2 exon 12 mutations in JAK2V617F-negative polycythemia vera. Leukemia. 2007;21:1960–1963. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larsen T.S., Pallisgaard N., Moller M.B., Hasselbalch H.C. Quantitative assessment of the JAK2 V617F allele burden: equivalent levels in peripheral blood and bone marrow (letter to the editor) Leukemia. 2008;22:194–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.James C., Delhommeau F., Marzac C., Teyssandier I., Couedic J.P., Giraudier S., Roy L., Saulnier P., Lacroix L., Maury S., Tulliez M., Vainchenker W., Ugo V., Casadevall N. Detection of JAK2 V617F as a first intention diagnostic test for erythrocytosis. Leukemia. 2006;20:350–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pietra D., Li S., Brisci A., Passamonti F., Rumi E., Theocharides A., Ferrari M., Gisslinger H., Kralovics R., Cremonesi L., Skoda R., Cazzola M. Somatic mutations of JAK2 exon 12 in patients with JAK2 (V617F)-negative myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2008;111:1686–1689. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinaud C., Brisou P., Mozziconacci M.J. Is the JAK2(V617F) mutation detectable in healthy volunteers? Am J Hematol. 2010;85:287–288. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21627. (letter to the editor) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tefferi A., Sirhan S., Lasho T.L., Schwager S.M., Li C.Y., Dingli D., Wolanskyj A.P., Steensma D.P., Mesa R., Gilliland D.G. Concomitant neutrophil JAK2 mutation screening and PRV-1 expression analysis in myeloproliferative disorders and secondary polycythaemia. Br J Haematol. 2005;131:166–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scott L.M., Scott M.A., Campbell P.J., Green A.R. Progenitors homozygous for the V617F mutation occur in most patients with polycythemia vera, but not essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2006;108:2435–2437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quintas-Cardama A., Kantarjian H., Manshouri T., Luthra R., Estrov Z., Pierce S., Richie M.A., Borthakur G., Konopleva M., Cortes J., Verstovsek S. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a yields high rates of hematologic and molecular response in patients with advanced essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5418–5424. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quintas-Cardama A., Kantarjian H.M., Manshouri T., Thomas D., Cortes J., Ravandi F., Garcia-Manero G., Ferrajoli A., Bueso-Ramos C., Verstovsek S. Lenalidomide plus prednisone results in durable clinical, histopathologic, and molecular responses in patients with myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4760–4766. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tefferi A., Lasho T.L., Mesa R.A., Pardanani A., Ketterling R.P., Hanson C.A. Lenalidomide therapy in del(5)(q31)-associated myelofibrosis: cytogenetic and JAK2V617F molecular remissions (letter to the editor) Leukemia. 2007;21:1827–1828. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kroger N., Badbaran A., Holler E., Hahn J., Kobbe G., Bornhauser M., Reiter A., Zabelina T., Zander A.R., Fehse B. Monitoring of the JAK2-V617F mutation by highly sensitive quantitative real-time PCR after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with myelofibrosis. Blood. 2007;109:1316–1321. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Passamonti F., Rumi E., Pietra D., Elena C., Boveri E., Arcaini L., Roncoroni E., Astori C., Merli M., Boggi S., Pascutto C., Lazzarino M., Cazzola M. A prospective study of 338 patients with polycythemia vera: the impact of JAK2 (V617F) allele burden and leukocytosis on fibrotic or leukemic disease transformation and vascular complications. Leukemia. 2010;24:1574–1579. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tefferi A., Lasho T.L., Huang J., Finke C., Mesa R.A., Li C.Y., Wu W., Hanson C.A., Pardanani A. Low JAK2V617F allele burden in primary myelofibrosis, compared to either a higher allele burden or unmutated status, is associated with inferior overall and leukemia-free survival. Leukemia. 2008;22:756–761. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guglielmelli P., Barosi G., Specchia G., Rambaldi A., Lo Coco F., Antonioli E., Pieri L., Pancrazzi A., Ponziani V., Delaini F., Longo G., Ammatuna E., Liso V., Bosi A., Barbui T., Vannucchi A.M. Identification of patients with poorer survival in primary myelofibrosis based on the burden of JAK2V617F mutated allele. Blood. 2009;114:1477–1483. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-216044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]