Abstract

BACKGROUND

American Samoa and Samoa are now characterized by one of the world's highest levels of adult overweight and obesity. Our objective was to investigate patterns of menstrual cyclicity reported by Samoan women and examine the relationship to adiposity and select hormone levels.

METHODS

A cross-sectional analysis was performed among Samoan women, aged 18–39 years (n = 322), using anthropometric and biomarker measures of adiposity and reproductive health, including insulin, adiponectin, testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, free androgen index (FAI) and mullerian-inhibiting substance (MIS). Menstrual regularity was assessed from self-reported responses. Multivariable models were estimated to adjust for potential confounding of the associations between menstrual patterns and other measures.

RESULTS

A high proportion of the women (13.7%) reported oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea (OM/AM). More than three-quarters, 80.7%, of women were either overweight or obese, using Polynesian-specific criteria, and OM/AM was significantly associated with higher BMI. Abdominal circumference and insulin levels were significantly higher, and adiponectin levels were lower, in those who reported OM/AM versus regular menstruation. The FAI was higher in women with increased BMI. MIS levels declined with age, more slowly in those reporting OM/AM.

CONCLUSIONS

Self-reported OM/AM was associated with an elevated BMI, abdominal adiposity and serum insulin, and with reduced adiponectin levels. These findings support a high rate of metabolic syndrome, and perhaps PCOS and reproductive dysfunction, among Samoan women.

Keywords: obesity, androgen, Samoans, polycystic ovary syndrome, MIS

Introduction

Many developing countries are experiencing a rise in obesity and chronic non-communicable diseases attributable to nutritional transitions. Diets have changed from consumption of complex carbohydrates and fiber to a more varied diet, with a higher proportion of fat, saturated fat and sugars (Popkin and Gordon-Larsen, 2004; Astrup et al., 2008). Physical activity has decreased due to occupational changes with economic development (Popkin and Gordon-Larsen, 2004). Increases in obesity-associated conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (Bjorntorp, 1997), hypertension (Palmieri et al., 2001) and ischemic heart disease (Cooper et al., 2000) are noted in men and women.

Multiple studies have found associations between overweight or obesity and irregular menstruation in women (Vague et al., 1970; Burghen et al., 1980; Bjorntorp, 1985; Kissebah et al., 1985; Kirschner et al., 1990; Pasquali et al., 2003). The risks for oligomenorrhea (OM) and amenorrhea (AM) increase 2-fold with each increase in obesity grade (Castillo-Martinez et al., 2003). Adipose tissue appears to exert its greatest effects on reproductive cyclicity via complex mechanisms involving hyperandrogenism and hyperinsulinemia.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a disorder linked closely with metabolic syndrome and hyperandrogenism, is the leading cause of anovulatory infertility worldwide, afflicting about 6% of women globally (Rodin et al., 1998; Diamanti-Kandarakis et al., 1999; Asunción et al., 2000; Azziz et al., 2004). Although its mechanisms of action appear complex, adipose tissue appears to play an important role in the development and sustainment of PCOS pathology; anywhere from 38 to 88% of all women with PCOS are overweight or obese, and even slight reductions in the body weight (i.e. 5%) are associated with significant improvement in the features of PCOS (Kiddy et al., 1992; Balen et al., 1995; Legro, 2000).

The Samoan islands, an archipelago of islands in the South Pacific Ocean, consist of American Samoa and Samoa, and are now characterized by one of the world's highest levels of adult overweight and obesity. In the last 30 years in particular, economic, dietary, physical activity and obesity patterns consistent with the nutrition transition have changed rapidly (McGarvey and Baker, 1979; Taylor and Zimmet, 1981; Baker et al., 1986; McGarvey 1991; Galanis et al., 1999). The contemporary chronic positive energy balance, which has led to high rates of obesity, especially in women, 75% in American Samoa and 59% in Samoa (Keighley et al., 2006), may have profound negative impacts upon the reproductive health status of women. The purpose of this report is to explore the impact of obesity on menstrual and endocrine function in Samoan women from both polities for the first time, with particular focus on risk factors for PCOS.

Materials and Methods

Study sample

The study population consisted of ethnic Samoan residents (who self-reported having four Samoan grandparents) of the independent nation of Samoa and the US territory of American Samoa. Participants were between 18 and 39 years of age, and were a sub-sample, as described below, of women of reproductive age who took part in a genetic epidemiology study of adiposity in both polities in 2002–2003 (Dai et al., 2007, 2008). The Brown University Institutional Review Board (IRB), the American Samoan IRB and the Samoa Health Research Committee approved the data collection and secondary analysis of the information. All subjects provided informed consent before participation in the study.

The genetic epidemiology study sample included a total of 2558 individuals aged 4–80 years, 1227 American Samoans and 1331 Samoans from extended pedigrees. Subjects in American Samoa were recruited based on selection from a 1990–1994 cohort study, with the additional requirement that participants had at least two adult siblings residing in American Samoa (Dai et al., 2007). Subjects in Samoa initially were recruited if they were members of American Samoa pedigrees, and later recruited in villages to represent the geographic and socioeconomic diversity within the nation (Dai et al., 2008). Comparison of the education and occupation distribution by age and gender of study participants with the 2000 census of American Samoa and the 2001 census of Samoa showed high similarity (Census of Population and Housing, 2001, 2004).

From the original study sample, male subjects were eliminated (n = 1210) and of the remaining 1348 females, women aged 18–39 years were selected (n = 469). We chose to eliminate adolescents who may have not established regular menstrual patterns, as well as to remove those older women who may be experiencing menstrual irregularity associated with peri-menopause/menopause. We excluded those who had undergone a hysterectomy, ovariectomy or other unspecified pelvic surgery (n = 56), those who reported being pregnant or lactating as a reason for their irregular cycles (n = 14), those with missing serum data (n = 7) and those with missing data on the self-reported menstrual patterns questions (n = 69), yielding a study sample of n = 323. One additional woman was removed following mullerian-inhibiting substance (MIS) analysis due to an extreme outlier MIS value (45 ng/ml) suggestive of an ovarian tumor (Lane et al., 1999) or other possible pathologic process. The final study sample totaled 322 women, 167 from Samoa and 155 from American Samoa.

Measurements

Standard anthropometric techniques were used to measure stature, weight and circumferences (Lohman et al., 1988). Underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity were defined using Polynesian-specific categories of BMI based on ‘gold standard’ body composition assessment: <22; 22–25.99; 26–32; and >32 kg/m2, respectively (Swinburn et al., 1999). These BMI categories exceed those used in the USA population, where 18.5–24.9 is normal weight, 25–29.9 is overweight and >30 kg/m2 is obese (CDC, 2007). Abdominal circumference was used as the primary measure of central fat distribution.

Fasting blood specimens were collected after a 10 h minimum overnight fast, separated with a portable field centrifuge and stored in plastic storage tubes at −40°C in local freezers. Serum was shipped on dry ice to Providence and stored at −80°C. Levels of glucose, insulin and adiponectin were previously measured as described (Aberg et al., 2008; Dibello et al., 2009a). Women were classified as diabetic if fasting serum glucose was ≥126 mg/dl, or by self-report of diabetes or diabetes medication.

Serum androgen levels were determined by measurements of total testosterone (TT) and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) using the Siemens Immulite instrument (Los Angeles, CA, USA). The calibration range for the TT assay was 0.7–55 nmol/l with an analytical sensitivity of 0.5 nmol/l. TT levels were below the limit of detection for 10 participants (low values were imputed for statistical analyses). The calibration range for the SHBG assay was up to 180 nmol/l with an analytical sensitivity <0.02 nmol/l. The inter-assay coefficients of variation were 14 and 9% for TT and SHBG, respectively. Free androgen index (FAI) was calculated as (TT * 100)/SHBG. Hyperandrogenemia was defined as above the median FAI, 4.3, in relatively low BMI, <26 kg/m2, Samoan women with normal menstrual cycles. Serum MIS levels were measured to assess ovarian reserve in Samoan women, using an ELISA method (Beckman Coulter, Chaska, MN, USA). The minimal detectable concentration of MIS was 0.10 ng/ml and assay coefficients of variation were <15%.

A health questionnaire was administered including a series of six questions about last menstrual period and history of pelvic surgery. We defined AM based on the answer ‘no’ to the question ‘have you gotten a period within the past year?’ OM was defined by the answer ‘3–6 months or longer’ to the question ‘about how long ago was your last period?’ Women who answered that they were having their period at the time of the survey, had gotten it 1 month ago, or had gotten it 1–3 months prior to the survey were classified in this study as having regular menstrual cycles.

Statistical analyses

Univariate analyses were performed to calculate frequencies, means with standard deviations and medians. Spearman correlations were used to estimate the associations among the hormone values, age and body size and fatness measures. Hormone levels were log-10 transformed in bivariate analyses. We used t-tests to detect differences in the means of continuous variables between the regular versus OM/AM groups. We tested for differences in proportions of categorical variables in the two groups using contingency tables and χ2 tests.

Multiple regression was performed to adjust for age effects on the association between OM/AM and abdominal circumference. When testing for the significance of insulin, all subjects who were previously labeled as diabetic were excluded from the analysis. We tested for interactions only among variables which we thought important based on the literature or on our bivariate results. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.0 (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant except for cases of multiple comparisons (correlation analysis) where P < 0.01 was used.

Results

Among women aged 18–39 years, 13.7% (44/322) reported not having a menstrual period within 3 (OM) to 12 (AM) months before the interview. Among these women, 95% reported the absence of menstruation for 1 year (AM). There was no difference in proportions of women with OM/AM between relatively younger (18–29 years) and older (30–39 years) groups and no difference in mean age between the groups (Table I). As expected, mean BMI in the sample was high, 33.6 kg/m2 (SD = 8.2; Table I). There was an association (P = 0.05) between BMI and menstrual status, with higher mean BMI in the OM/AM group. In addition, there was a significant association (P < 0.05) between BMI classification and menstrual status in the OM/AM group; more than two-thirds of these women were obese (Table I). Abdominal circumference was higher in women reporting OM/AM (P = 0.006). The association of abdominal circumference and OM/AM (P < 0.001), but not BMI (P = 0.09), remained when accounting for age effects.

Table I.

Description of demographic information and hormone levels in Samoan women overall and categorized by menstrual status.

| All women (n = 322) | OM/AMa, 13.7% (n = 44) | Regular menstruationa, 86.3% (n = 278) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.4 (6.8) 30.5 | 30.3 (5.9), 31.6 | 29.2 (6.9), 30.2 |

| 18–29.9 | 47.8% | 40.9% | 48.9% |

| 30–39.9 | 52.2% | 59.1% | 51.1% |

| BMIb (kg/m2) | 33.6 (8.2) 32.8 | 35.8 (8.3), 34.1* | 33.2 (8.2), 32.5 |

| <26 | 19.3% | 11.4%c,** | 20.5% |

| 26–32 | 27.0% | 20.5% | 28.1% |

| >32 | 53.7% | 68.2% | 51.4% |

| Abdominal circum. (cm) | 103.6 (17.2) 104.1 | 110.3 (18.8), 110.2** | 102.6 (16.8), 103.4 |

| Adiponectin (µg/ml)d | 11.1 (9.4) 9.2 | 9.4 (6.2), 7.5** | 11.4 (9.8) 9.5 |

| Insulin (µU/ml)d | 14.1 (17.6) 9.3 | 21.6 (34.7), 11.6 ** | 12.9 (12.7), 9.1 |

| Type 2 diabetese | 6.2% | 9.1% | 5.8% |

| MIS (ng/ml)d | 2.1 (2.0) 1.7 | 2.0 (1.6), 1.6 | 2.2 (2.1), 1.7 |

| Testosterone (nmol/l)d | 2.5 (1.4) 2.3 | 2.2 (1.3), 1.9* | 2.6 (1.4), 2.4 |

| SHBG (nmol/l)d | 49.4 (47.9) 36.5 | 40.5 (25.0), 34.0 | 50.8 (50.4), 36.7 |

| FAI | 7.8 (6.8) 5.7 | 7.7 (9.2), 5.5 | 7.8 (6.3), 5.8 |

Mean, (standard deviation), and median reported for all variables.

aOM and AM are defined as: AM—the answer ‘No’ to the question ‘have you gotten your period in the last year?’, and OM—the answer ‘3–6 months or longer’ to the question ‘about how long ago was your last period?’ Regular menstruation is defined as a subject having answered ‘Yes’ to the question ‘have you gotten your period in the last year?’ and the answers ‘in the last month’, or ‘1–3 months ago’ to the question ‘about how long ago was your last period?’

bPolynesian BMI classifications (see text), in percent.

cAssociation between BMI categories and menstrual status.

dFor comparison of means, adiponectin, insulin, MIS, testosterone and SHBG were log-10 transformed.

eFasting serum glucose ≥126 mg/dl, or self-report of diabetes.

*0.05 < P < 0.10, **P < 0.05—difference in means by menstrual status.

Among all women 6.2% had type 2 diabetes; 9.1% among those with OM/AM and 5.8% among those with regular menstrual patterns. This difference was not statistically significant. Fasting insulin was higher in those with OM/AM (P = 0.03) and this association remained after age adjustment. Adiponectin levels were lower (P = 0.04) in women reporting OM/AM. In contrast, comparing measures of androgen status, TT levels were slightly lower in the OM/AM group, but SHBG levels and the FAI did not differ (Table I).

BMI was a strong predictor of serum FAI. Samoan women with a relatively high BMI (>26 kg/m2) had a significantly higher FAI level than those with a lower BMI (P < 0.0001). The median serum FAI level in Samoan women with a BMI below 26 kg/m2 was 4.3. Hyperandrogenemia, FAI > 4.3, was present in 67% (215/322) of the sample. Approximately 8% of women had a combination of irregular menstrual cycles and hyperandrogenemia (Table II). BMI and abdominal circumference were highly correlated, as expected (Table III). Both of these measures showed positive correlations with the FAI and insulin, and negative correlations with SHBG, adiponectin and MIS (Table III).

Table II.

Stratification of Samoan women by menstrual cycle regularity and androgen status.

| Menstrual status |

||

|---|---|---|

| Regular cycles | OM/AM | |

| Normoandrogenemia | 90 (27.9%) | 17 (5.3%) |

| Hyperandrogenemiaa | 188 (58.4%) | 27 (8.4%) |

aDefined using median FAI in relatively low BMI Samoan women with regular menstrual cycles (>4.3).

Table III.

Spearman correlations of BMI and abdominal circumference with hormone levels and age in Samoan women.

| Testo | SHBG | FAI | MIS | Insulin | Adipo | Age | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 0.11 | −0.43** | 0.38** | −0.18** | 0.61** | −0.35** | 0.35** | |

| Abd cir. | 0.09 | −0.33** | 0.28** | −0.21** | 0.56** | −0.31** | 0.38** | 0.90** |

Testo, total testosterone; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; FAI, free androgen index; MIS, mullerian-inhibiting substance; Adipo, adiponectin; BMI, body mass index; Abd cir, abdominal circumference.

**P < 0.01.

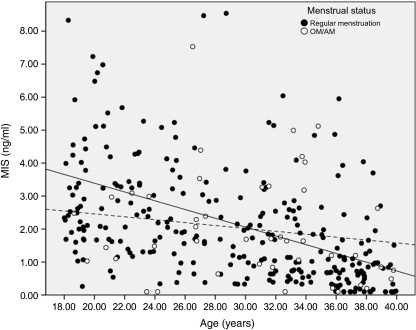

There was an interaction between age and menstrual status on serum MIS levels. MIS was negatively associated with age in the entire sample (r = −0.52, P < 0.001) as expected. However, MIS levels remained inversely related to age in the regularly menstruating women (r = −0.44, P < 0.001), but not in those with OM/AM (r = −0.16, N.S.; Fig. 1). This difference remained after adjustment of MIS levels for BMI.

Figure 1.

Relationship between MIS and age when stratified between menstrual status groups. Regression lines have been fit to regularly menstruating women (solid line, MIS = 6.05–0.133 × Age, r = −0.44, P < 0.001) and OM/AM women (dotted line, MIS = 3.34–0.044 × Age, r = −0.16, P = 0.299). Note: two normally menstruating women with high MIS values (13 and 20 ng/ml) are not shown.

Discussion

The well-characterized obesity of contemporary Samoans stimulated this exploratory study (McGarvey and Baker, 1979; McGarvey, 1991; Keighley et al., 2006). We found a high proportion of irregular menstrual cycles, 13.7%, among Samoan women aged 18–39 years. Women of reproductive age, who are not pregnant or lactating, are expected to menstruate regularly, although some variation in the cycle length occurs (Münster et al., 1992; Astrup, 2004). Few studies have examined the prevalence of AM within women in communities (Bachman and Kemmann, 1982; Kjaer et al., 1992; Jabbar et al., 2004; Gorrindo et al., 2007). In one such study, 2.8% of 18–49-year-old women in an otherwise healthy control group had AM, and 10.8% experienced menstrual dysfunction (Kjaer et al., 1992). The present proportion of OM/AM appears to be high, although these initial results should be interpreted with caution.

A recent population-level study by Wei et al. (2009) has demonstrated that increased BMI, FAI, serum T and insulin, as well as decreased levels of serum SHBG, are all independently associated with increased likelihood of menstrual irregularity in reproductive age women. Adiponectin levels are inversely related to serum insulin and androgens, and are reduced in women diagnosed with PCOS, especially those with obesity (reviewed in Michalakis and Segars, 2010). Among the variables studied presently, BMI, adiponectin and insulin levels were significantly associated with reports of menstrual irregularity. Insulin levels were higher in women with OM/AM, even after adjustment for abdominal circumference or BMI and age. Because of the cross-sectional design of the exploratory study, it is impossible to infer causation. Yet, an association of obesity and insulin in women with PCOS is well described (Dunaif et al., 1987; Linné, 2004; Bhatia, 2005), raising this possible diagnosis for further study in Samoan women.

PCOS is defined by anovulatory menstrual cycles with either polycystic ovary morphology on ultrasound or biochemical or clinical hyperandrogenism (Fauser and Laven, 2004; Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group, 2004a,b). Women in American Samoa and Samoa rarely have ovarian ultrasounds and data on clinical evidence of hirsutism were not available. We therefore assessed serum androgens in this population. There is no standard definition for biochemical hyperandrogenism in women with PCOS. Hahn et al. (2007) showed that the FAI better discriminated PCOS than did TT or SHBG. As expected, a relatively high BMI was associated with an increased FAI. The median FAI in Samoan women with BMI values <26 kg/m2 and regular menstrual cycles were used to determine a cutoff value for what might constitute hyperandrogenemia in this population. Although the FAI in Samoan women did not differ based on menstrual cycle history, most (67%) showed comparatively high androgen levels. Moreover, 12.6% (27/215) of those with high androgen levels also had OM/AM; this combination is suggestive of PCOS. Further study of the normal distribution of serum androgen levels in the Samoan women is required, as ethnic variation in normative data has been reported (Williamson et al., 2001).

Numerous recent studies suggest that serum levels of the glycoprotein MIS may be used as an indirect biomarker for polycystic ovaries, through a close relationship with ovarian antral follicle count (de Vet et al., 2002; Pigny et al., 2003; Laven et al., 2004; Fiçicioglu et al., 2006; Nakhuda et al., 2006; Codner et al., 2007). Most studies show elevated serum MIS levels in women suffering from PCOS (Pigny et al., 2003; Laven et al., 2004; Mulders et al., 2004; Piltonen et al., 2005; Codner et al., 2007; Piouka et al., 2009), reflecting impaired follicle development and ovulation (higher retention of small follicles). We found no difference in mean MIS levels between regularly menstruating Samoans and those self-reporting OM/AM. Yet, MIS levels in the present study (mean = 2.1 ng/ml) were between those expected in women with PCOS and those with regular cycles (Pigny et al., 2003; Laven et al., 2004; Mulders et al., 2004; Piltonen et al., 2005; Codner et al., 2007; Freeman et al., 2007; Piouka et al., 2009). The high BMI characterizing the sample (mean = 33.62 kg/m2) is greater than the criterion for obesity, even after adjusting to the Polynesian scale, and represents a BMI distribution unlike that found in any previous study of MIS. Since BMI has a profound negative relationship with serum MIS (Freeman et al., 2007; Su et al., 2008), a blunted effect on MIS might be expected in the very obese Samoan women. Other possible factors influencing MIS levels in Samoan women are ethnic variation (Seifer et al., 2009) or the extent of PCOS, since mild cases are associated with relatively small increases in serum MIS (Laven et al., 2004). Lastly, age is a covariate of serum MIS, with levels declining as women get older. Of interest, there was an interaction of age and menstrual cycle regularity in the present study. Women reporting irregular cycles had a slower rate of decline in MIS, consistent with the possibility of anovulatory PCOS.

No previous research has been performed on ovarian function, patterns of menstruation or OM/AM among Samoan women in the archipelago. In addition, while many researchers have examined female reproductive dysfunction, this is the first report in a community-based sample characterized by extremely high rates of overweight and obesity. However, the survey was not designed specifically with the intent to study menstrual cycle regularity and should be extended and refined for future studies. The nature of the main study design and data collection was a genetic epidemiology investigation of adiposity among large extended families. Thus, the participants had some degree of family relatedness among them, which was not adjusted for in the analysis. Furthermore, analysis of serum reproductive hormone levels was performed on a single sample collected from each woman without regard to the menstrual cycle day. If timed samples were available, measurement of progesterone could be used to identify anovulatory cycles. Interpretation of serum testosterone results would also be improved by timed samples since levels are known to peak at mid-cycle (Mushayandebvu et al., 1996).

While we acknowledge the limited nature of the present survey and self-reports of menstruation, our estimate of cycle irregularity is conservative. We made broad exclusions of women who might be expected to have irregular cycles (<18 or older than 39). Also, although we did not include a survey of contraceptive use in the present study, in earlier work in 1993 in (Western) Samoa, only 20% of married women 25–39 years of age used any type of exogenous hormones for contraception including oral contraceptive pills or Depo-Provera (Brewis et al., 1998). Yet, use of hormonal contraceptives would provide for more, not less, regular menstrual cycles. Oral contraceptive pills also improve (reduce) insulin and testosterone levels (Mulders et al., 2005; Costello et al., 2007) and have no effect on serum MIS levels (Somunkiran et al., 2007).

Regardless of limitations, this study of Samoan women shows a high rate of menstrual irregularity associated with high serum insulin, BMI and abdominal circumference measurements, and with low serum adiponectin levels. The FAI was correlated with obesity, and MIS levels declined more slowly with age in those with irregular versus regular menstrual cycles. These findings corroborate earlier work demonstrating a high level of metabolic syndrome among Samoan women (DiBello et al., 2009b), and suggest possible reproductive dysfunction. This group may serve as a model population for further study of the impact of obesity on susceptibility genes for adverse reproductive conditions, especially those complicated by metabolic dysfunction, such as PCOS.

Authors’ roles

J.A.-C., S.V., S.T.M. and G.L.-M. were responsible for study design and sample and data collection. S.S.U. contributed serum measurement data. S.S.U., M.B.R., S.T.M., M.U. and G.L.-M. performed analyses and drafted the paper. All authors provided critical discussion and manuscript review.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH Grants DK59642 and DK075371 (S.T.M.) and unrestricted research funding from Beckman Coulter Inc (G.L.-M). M.B.R., S.U., J.A., S.V. and M.U. have nothing to disclose.

References

- Aberg K, Dai F, Sun G, Keighley E, Indugula SR, Bausserman L, Viali S, Tuitele J, Deka R, Weeks DE, et al. A genome-wide linkage scan identifies multiple chromosomal regions influencing serum lipid levels in the population on the Samoan islands. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2169–2178. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800194-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrup K. Menstrual bleeding patterns in pre- and perimenopausal women: population-based prospective diary study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrup A, Dyerberg J, Selleck M, Stender S. Nutrition transition and its relationship to the development of obesity and related chronic diseases. Obes Rev. 2008;9(S1):48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asunción M, Calvo RM, San Millán JL, Sancho J, Avila S, Escobar-Morreale HF. A prospective study of the prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected Caucasian women from Spain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2434–2438. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.7.6682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2745–2749. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann GA, Kemmann E. Prevalence of oligomenorrhea and amenorrhea in a college population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:98–102. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PT, Hanna JM, Baker TS. The Changing Samoans: Behavior and Health in Transition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Balen AH, Conway GS, Kaltsas G, Techatrasak K, Manning PJ, West C, Jacobs HS. Polycystic ovary syndrome: the spectrum of the disorder in 1741 patients. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2107–2111. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovarian disease. South Med J. 2005;98:903–910. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000177251.15366.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorntorp P. Regional Patterns of Fat Distribution. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:994–995. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-6-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorntorp P. Body fat distribution, insulin resistance, and metabolic diseases. Nutrition. 1997;13:795–803. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis AA, McGarvey ST, Tu'u'au-Potoi N. Structure of family planning in Samoa. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1998;22:424–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghen GA, Givens JR, Kitabchi AE. Correlation of hyperandrogenism with hyperinsulinism in polycystic ovarian disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;50:113–116. doi: 10.1210/jcem-50-1-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Martinez L, Lopez-Alvarenga JC, Villa AR, Gonzalez- Barranco J. Menstrual cycle length disorder in 18- to 40-y-old obese women. Nutrition. 2003;19:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(02)00998-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/bmi/adult_BMI/about_adult_BMI.htm. (28 December 2007, date last accessed)

- Census of Population and Housing. Government of Samoa. Apia: Department of Statistics, Government of Samoa; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Census of Population and Housing. American Samoa 2000. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Codner E, Iñíguez G, Villarroel C, Lopez P, Soto N, Sir-Petermann T, Cassorla F, Rey RA. Hormonal profile in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome with or without type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4742–4746. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R, Cutler J, Desvigne-Nickens P, Fortmann SP, Firedman L, Havlik R, Hogelin G, Marler J, McGovern P, Morosco G, et al. Trends and disparities in coronary heart disease, stroke and other cardiovascular diseases in the United States: findings of the national conference on cardiovascular disease prevention. Circulation. 2000;102:3137–3147. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello MF, Shrestha B, Eden J, Johnson NP, Sjoblom P. Metformin versus oral contraceptive pill in polycystic ovary syndrome: a Cochrane review. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1200–1209. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai F, Keighley ED, Sun G, Indugula SR, Roberts ST, Aberg K, Smelser D, Tuitele J, Jin L, Deka R, et al. Genome-wide scan for adiposity-related phenotypes in adults from American Samoa. Int J Obes. 2007;31:1832–1842. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai F, Sun G, Aberg K, Keighley ED, Indugula SR, Roberts ST, Smelser D, Viali S, Jin L, Deka R, et al. A whole genome linkage scan identifies multiple chromosomal regions influencing adiposity-related traits among Samoans. Ann Hum Genet. 2008;72:780–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vet A, Laven JS, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, Fauser BC. Antimüllerian hormone serum levels: a putative marker for ovarian aging. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:357–362. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02993-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Kouli CR, Bergiele AT, Filandra FA, Tsianateli TC, Spina GG, Zapanti ED, Bartzis MI. A survey of the polycystic ovary syndrome in the Greek island of Lesbos: hormonal and metabolic profile. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4006–4011. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBello JR, Baylin A, Viali S, Tuitele J, Bausserman L, McGarvey ST. Adiponectin and type 2 diabetes in Samoan adults. Am J Hum Biol. 2009a;21:389–391. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBello JR, DiBello JR, McGarvey ST, Kraft P, Goldberg R, Campos H, Quested C, Laumoli TS, Baylin A. Dietary patterns are associated with metabolic syndrome in adult Samoans. J Nutrition. 2009b;139:1933–1943. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.107888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunaif A, Graf M, Mandeli J, Laumas V, Dobrjansky A. Characterization of groups of hyperandrogenic women with acanthosis nigricans, impaired glucose tolerance, and/or hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;65:499–507. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-3-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauser BC, Laven JS. Role of estrogens in ovarian dysfunction and fertility. Options for new therapies with SERMs. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop. 2004;46:169–179. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05386-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiçicioglu C, Kutlu T, Baglam E, Bakacak Z. Early follicular antimüllerian hormone as an indicator of ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:592–596. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman EW, Gracia CR, Sammel MD, Lin H, Lim LC, Strauss JF., 3rd Association of anti-mullerian hormone levels with obesity in late reproductive-age women. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanis DJ, McGarvey ST, Quested C, Sio B, Afele-Fa'amuili SA. Dietary intake of modernizing Samoans: implications for risk of cardiovascular disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:184–190. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorrindo T, Lu Y, Pincus S, Riely A, Simon JA, Singer BH, Weinstein M. Lifelong menstrual histories are typically erratic and trending: a taxonomy. Menopause. 2007;14:74–88. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000227853.19979.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S, Kuehnel W, Tan S, Kramer K, Schmidt M, Roesler S, Kimmig R, Mann K, Janssen OE. Diagnostic value of calculated testosterone indices in the assessment of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:202–207. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar S. Frequency of primary amenorrhea due to chromosomal aberration. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14:329–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keighley ED, McGarvey ST, Turituri P, Viali S. Farming and adiposity in Samoan Adults. Am J Hum Biol. 2006;18:112–122. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiddy DS, Hamilton-Fairley D, Bush A, Short F, Anyaoku V, Reed MJ, Franks S. Improvement in endocrine and ovarian function during dietary treatment of obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1992;36:105–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner MA, Samojlik E, Drejka M, Szmal E, Schneider G, Ertel N. Androgen-estrogen metabolism in women with upper body versus lower body obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:473–479. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-2-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissebah A, Evans DP, Peiris A, Wilson CR. Endocrine characteristics in regional obesities: role of sex steroids. In: Vague J, Bjorntorp P, Guy-Grand B, Rebuffe-Scrive M, Vague P, editors. Metabolic Complications of Human Obesities. Amsterdam, NL: Elsevier Scientific Publisher; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer K, Hagen C, Sandø SH, Eshøj O. Epidemiology of menarche and menstrual disturbances in an unselected group of women with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus compared to controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:524–529. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.2.1639955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane AH, Lee MM, Fuller AF, Jr, Kehas DJ, Donahoe PK, MacLaughlin DT. Diagnostic utility of Müllerian inhibiting substance determination in patients with primary and recurrent granulosa cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:51–55. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laven JS, Mulders AG, Visser JA, Themmen AP, De Jong FH, Fauser BC. Anti-Müllerian hormone serum concentrations in normoovulatory and anovulatory women of reproductive age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:318–323. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legro RS. The genetics of obesity: lessons for polycystic ovary syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;900:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linné Y. Effects of obesity on women's reproduction and complications during pregnancy. Obes Rev. 2004;5:137–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manuals. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey ST. Obesity in Samoans and a perspective on its etiology in Polynesians. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;56:1586s–1594s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.6.1586S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey ST, Baker PT. The effects of modernization and migration on Samoan blood pressures. Hum Biol. 1979;51:461–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalakis KG, Segars JH. The role of adiponectin in reproduction: from polycystic ovary syndrome to assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1949–1957. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders AG, Laven JS, Eijkemans MJ, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, Fauser BC. Changes in anti-Müllerian hormone serum concentrations over time suggest delayed ovarian ageing in normogonadotrophic anovulatory infertility. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2036–2042. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders AG, ten Kate-Booij M, Pal R, De Kruif M, Nekrui L, Oostra BA, Fauser BC, Laven JS. Influence of oral contraceptive pills on phenotype expression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;11:690–696. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61687-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münster K, Schmidt L, Helm P. Length and variation in the menstrual cycle—a cross-sectional study from a Danish country. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:422–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushayandebvu T, Castracane VD, Gimpel T, Adel T, Santoro N. Evidence for diminished midcycle ovarian androgen production in older reproductive aged women. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:721–723. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakhuda GS, Chu MC, Wang JG, Sauer MV, Lobo RA. Elevated serum müllerian-inhibiting substance may be a marker for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in normal women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1541–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri V, de Simone G, Arnett DK, Bella JN, Kitzman DW, Oberman A, Hopkins PN, Province MA, Devereux RB. Relation of various degress of body mass index in patients with systemic hypertension to left ventricular mass, cardiac output, and peripheral resistance (The Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network Study) Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:1163–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali R, Pelusi C, Genghini S, Cacciari M, Gamineri A. Obesity and reproductive disorders in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:359–372. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigny P, Merlen E, Robert Y, Cortet-Rudelli C, Decanter C, Jonard S, Dewailly D. Elevated serum level of anti-mullerian hormone in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: relationship to the ovarian follicle excess and to the follicular arrest. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5957–5962. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piltonen T, Morin-Papunen L, Koivunen R, Perheentupa A, Ruokonen A, Tapanainen JS. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels remain high until late reproductive age and decrease during metformin therapy in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1820–1826. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piouka A, Farmakiotis D, Katsikis I, Macut D, Gerou S, Panidis D. Anti-Mullerian hormone levels reflect severity of PCOS but are negatively influenced by obesity: relationship with increased luteinizing hormone levels. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E238–E243. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90684.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. The nutrition transition: worldwide obesity dynamics and their determinants. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(S3):S2–S9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin DA, Bano G, Bland JM, Taylor K, Nussey SS. Polycystic ovaries and associated metabolic abnormalities in Indian subcontinent Asian women. Clin Endocrinol. 1998;49:91–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1998.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004a;81:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Hum Reprod. 2004b;19:41–47. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer DB, Golub ET, Lambert-Messerlian G, Benning L, Anastos K, Watts DH, Cohen MH, Karim R, Young MA, Minkoff H, et al. Variations in serum müllerian inhibiting substance between white, black, and Hispanic women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1674–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somunkiran A, Yavuz T, Yucel O, Ozdemir I. Anti-mullerian hormone levels during hormonal contraception in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;134:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su HI, Sammel MD, Freeman EW, Lin H, DeBlasis T, Gracia CR. Body size affects measures of ovarian reserve in late reproductive age women. Menopause. 2008;15:857–861. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318165981e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn BA, Ley SJ, Carmichael HE, Plank LD. Body size and composition in Polynesians. Int J Obes. 1999;23:1178–1183. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Zimmet PZ. Obesity and diabetes in Western Samoa. Int J Obes. 1981;5:367–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vague J, Vague P, Boyer J, Cloix MC. Anthropometry of obesity, diabetes, adrenal and beta-cell functions. In: Rodriguez RR, Vallance-Owen J, editors. Diabetes. Amsterdam, NL: Ed. Excerpta Medica; 1970. p. 517. [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Schmidt MD, Dwyer T, Norman RJ, Venn AJ. Obesity and menstrual irregularity: associations with SHBG, testosterone, and insulin. Obesity. 2009;17:1070–1076. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson K, Gunn AJ, Johnson N, Milsom SR. The impact of ethnicity on the presentation of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41:202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.2001.tb01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]