Summary

Formins are a conserved family of proteins with robust effects in promoting actin nucleation and elongation. However, the mechanisms restraining formin activities in cells to generate actin networks with particular dynamics and architectures are not well understood. In S. cerevisiae, formins assemble actin cables, which serve as tracks for myosin-dependent intracellular transport. Here, we show that the kinesin-like myosin passenger-protein Smy1 interacts with the FH2 domain of the formin Bnr1 to decrease rates of actin filament elongation, which is distinct from the formin displacement activity of Bud14. In vivo analysis of smy1Δ mutants demonstrates that this ‘damper’ mechanism is critical for maintaining proper actin cable architecture, dynamics, and function. We directly observe Smy1–3GFP being transported by myosin V and transiently pausing at the neck in a manner dependent on Bnr1. These observations suggest that Smy1 is part of a negative feedback mechanism that detects cable length and prevents overgrowth.

Keywords: actin, formin, Smy1, myosin, Bnr1, yeast, kinesin, Bud14

Introduction

Eukaryotic cells depend on the dynamic assembly and turnover of organized actin arrays for polarization, division, motility and morphogenesis. The architecture and properties of the filamentous networks underlying these processes are each highly unique (Chhabra and Higgs, 2007). One of the major control points in forming cellular actin structures is the nucleation and elongation of filaments, which is regulated by a set of conserved actin-assembly promoting factors (Chesarone and Goode, 2009). However, we have only a limited understanding of how the actin nucleation and elongation activities of these factors are precisely controlled in vivo to produce actin networks with specific dynamics and spatial organization.

Formins are one of the most widely expressed families of actin assembly promoting factors and have been shown to have essential roles in assembling many different actin-based structures, such as stress fibers, filopodia, cables, and cytokinetic rings (Chesarone et al., 2010; Goode and Eck, 2007). The core biochemical properties shared by most formins include an ability to: (i) directly nucleate actin filaments from a pool of monomers, (ii) remain processively attached to the growing barbed end of the filament and protect it from capping proteins, and (iii) recruit profilin-actin complexes to accelerate elongation of the filament barbed end (Kovar et al., 2006; Pruyne et al., 2002; Romero et al., 2004; Sagot et al., 2002b). The formin homology 2 (FH2) domain is a dimer, binds directly to actin, and is required and sufficient for nucleation and processive capping activities (Moseley et al., 2004; Pring et al., 2003; Pruyne et al., 2002; Sagot et al., 2002b). The adjacent FH1 domain contains multiple binding sites for profilin-actin and assists the FH2 domain in nucleation and elongation (Kovar et al., 2006; Kovar et al., 2003; Li and Higgs, 2003; Romero et al., 2004; Vavylonis et al., 2006). A number of in vivo studies have shown that expression of dominant active FH1-FH2 fragments stimulates the assembly of excessive, disorganized actin arrays (Sagot et al., 2002b, Evangelista et al. 2001.) These observations underscore the importance of restraining formin activities in vivo to prevent unregulated activity.

The precise mechanisms employed by cells to spatially and temporally restrict formin activities have remained somewhat obscure. A number of studies have clarified how formins are released from autoinhibition by Rho GTPases (Li and Higgs, 2003; Rose et al., 2005; Seth et al., 2006; Watanabe et al., 1999). However, little else is known about how formins, once activated, are temporally restricted to yield appropriate rates of nucleation and elongation. In principle, mechanisms may exist to control the nucleation efficiency of formins, increase or decrease the speed of filament elongation, and/or regulate the duration of processive capping. The delicate orchestration of these control points would allow cells to produce actin networks with specialized properties tailored to their biological functions.

We have begun to address these questions using S. cerevisiae as a model, because it enables parallel genetic and biochemical analyses of protein function. S. cerevisiae formins have an essential role in assembling actin cables, structures that serve as polarized tracks for type-V myosin dependent transport of secretory vesicles and other cargo toward the bud tip (Evangelista et al., 2002; Pruyne et al., 1998; Sagot et al., 2002a; Schott et al., 1999). Ultrastructural analysis in S. pombe has demonstrated that individual actin cables consist of many shorter overlapping actin filaments (0.4–0.5 microns in length), bundled and oriented with their barbed ends facing towards the bud tip (Kamasaki et al., 2005). To date, similar high resolution structural analysis of S. cerevisiae actin cables has not been carried out, but pharmacological assays suggest a similar architecture (Karpova et al., 1998). In budded S. cerevisiae cells, actin cable formation is nucleated from two cortical sites, the bud neck and the bud cortex, and from these positions cables extend into the cytoplasm at 0.4–2.0 µm/s (Huckaba et al., 2006; Pruyne et al., 2004; Yang and Pon, 2002; Yu et al., 2011).

The two formins expressed in S. cerevisiae, Bni1 and Bnr1, have distinct properties, locations, and regulation, but are genetically redundant (Imamura et al., 1997; Vallen et al., 2000). In budded cells, Bni1 particles are transiently recruited from the cytosol to the bud cortex (lifetime 10–15 s), where they assemble thin actin cables that fill the bud compartment, and sometimes pass through the neck into the mother (Buttery et al., 2007; Pruyne et al., 2004). In contrast, Bnr1 is stably tethered at the bud neck (lifetime >20 minutes), and assembles longer thicker cables that move less rapidly, specifically fill the mother compartment, and terminate near the rear of the cell (Buttery et al., 2007; Pruyne et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2011). It is not yet clear whether the slower dynamics of the actin cables generated by Bnr1 might be optimized for myosin-based transport in the mother cell, or how the activities of Bni1 and Bnr1 are differentially regulated to produce distinct cable lengths, speeds and architectures. It is also not yet clear how cells control the length of cables to prevent cable ‘overgrowth’ at the rear of the cell, which would result in misdirected secretory vesicle transport.

Previously, we showed that Bud14 functions as a formin displacement factor, binding to the FH2 domain of Bnr1 (but not Bni1) and disrupting the association of Bnr1 with the growing barbed end of the filament (Chesarone et al., 2009). Consistent with this biochemical activity, loss of BUD14 in vivo led to the assembly of abnormally long, buckled actin cables that were resistant to latrunculin A and caused defects in secretory vesicle transport and cell morphogenesis. This revealed that mechanisms regulating the duration of formin-mediated actin assembly events are important in vivo for maintaining normal organization of actin networks. Here, we investigated the role of Smy1 in regulating actin cable assembly. Smy1 is a distant member of the Kinesin 1 subfamily, but lacks detectable microtubule motor activity in vitro (Hodges et al., 2009), and does not require microtubules for its known in vivo functions (Lillie and Brown, 1998). Interestingly, like another kinesin I subfamily member, Kif5b/uKHC (Huang et al., 1999), Smy1 physically associates with type-V myosin (called Myo2 in S. cerevisiae) (Beningo et al., 2000; Hodges et al., 2009; Lillie and Brown, 1992, 1994; Schott et al., 1999). Further, Smy1 enhances the processivity of Myo2 on fascin-bundled actin filaments in vitro (Hodges et al., 2009), and promotes myosin-dependent polarized secretion in vivo (Beningo et al., 2000; Lillie and Brown, 1994, 1998). In vivo, Smy1 has been shown to colocalize with Sec4, a marker for Myo2-trafficked secretory vesicles (Schott et al., 2002), on actin cables (Hodges et al., 2009). Smy1 is also a binding partner of Bnr1 (Kikyo et al., 1999), but until now the functional significance of this interaction has not been investigated. Here, we report a biochemical and cellular function for Smy1 in directly regulating Bnr1 activity to maintain proper actin cable architecture and function in vivo.

Results

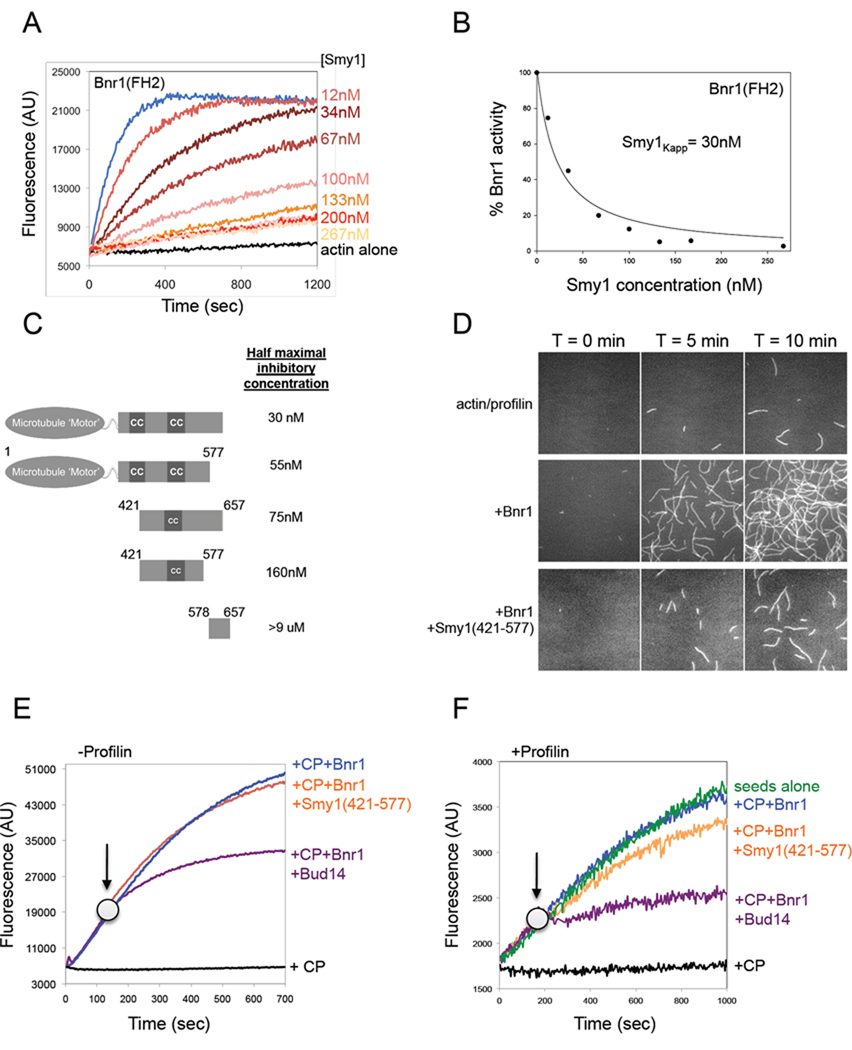

Smy1 directly inhibits the actin nucleation activity of Bnr1, but does not disrupt processive capping

To investigate Smy1 interactions with yeast formins, we expressed and purified full-length 6His-tagged Smy1 from E. coli. In pyrene-actin assembly assays, Smy1 had no effect on actin alone or on actin assembly stimulated by Bni1 (FH1-FH2-C) (Supplementary Figure 1, A and B). However, Smy1 strongly inhibited the actin assembly activity of Bnr1 (FH1-FH2-C) (Supplementary Figure 1, C and D). Similarly, Smy1 showed concentration-dependent inhibitory effects on the activity of 5nM Bnr1 FH2 domain (Figure 1, A), with half maximal inhibition occurring at 30nM Smy1 (Figure 1, B). The strength and specificity of these inhibitory effects suggests that there is a strong physical association between Smy1 and the FH2 domain of Bnr1 but not Bni1.This is also consistent with a previous study showing that Smy1 binds to the FH2 region of Bnr1 but not Bni1 (Kikyo et al., 1999).

Figure 1. Smy1 inhibits Bnr1 (FH2) actin nucleation activity, but not processive capping.

(A) Monomeric actin (2µM, 5% pyrene labeled) was polymerized in the presence of 5nM Bnr1 (FH2) and the indicated concentrations of Smy1. (B) Concentration-dependent inhibitory effects of Smy1 on Bnr1. Percent Bnr1 activity was determined by dividing the slope of the actin polymerization curve in the presence of Smy1 by the slope of the curve in the absence of Smy1. (C) Schematic of purified full length and truncated Smy1 polypeptides. Each polypeptide was compared at a range of concentrations for its inhibitory effects on Bnr1 (FH1-FH2-C) in pyrene-actin assays (see Supplementary Figure 1, H–J) to determine concentration required for half-maximal inhibition. (D) Time-lapse TIRF microscopy on assembly of 1µM actin and 3µM profilin in the presence of control buffer, 1nM Bnr1 (FH1-FH2-C) and/or 500nM Smy1 (421–577). (E) Effects of Smy1 and Bud14 on Bnr1-capped actin filament barbed end growth in the presence of capping protein (CP). At time zero, monomeric actin (0.5µM, 10% pyrene labeled) was added to mechanically sheered unlabelled F-actin seeds (0.3µM) in the presence of 0.7nM Bnr1 (FH1-FH2-C) and 500nM S. cerevisiae CP. At the indicated time point (arrow) either 500nM Bud14 (179–472) or 500nM Smy1 (421–577) was added. (F) Effects of Smy1 and Bud14 on Bnr1-capped actin filament barbed end growth in the presence of capping protein (CP) and profilin. Same as in E, but reactions contained 3µM profilin.

Smy1 has three identifiable domains: an N-terminal motor-like domain (1–375), a central cargo-binding domain (421–577) with predicted coiled coil stretches, and a C-terminal myosin-interacting domain (578–657) (Beningo et al., 2000). By comparing the abilities of Smy1 truncation mutants to inhibit Bnr1 activity (Figure 1C), we determined that the motor-like domain and the myosin-interacting domain are both dispensable for inhibition, and that the cargo-binding domain (421–577) contains most of the inhibitory activity (Figure 1, C and Supplementary Figure 1, H–J). Smy1 (421–577) inhibition activity was also verified by TIRF microscopy. Reactions containing 1µM G-actin and 3µM profilin alone showed very few filaments after 10 min. Addition of 1nM Bnr1 caused a dramatic increase in filament number at the same time point (Figure 1, D rows 1 and 2). Further addition of 500nM Smy1 (421–577) caused a major decrease in filament number (Figure 1, D row 3), consistent with Smy1 inhibiting Bnr1. Note that this concentration of Smy1 (421–577) only decreases Bnr1 activity in pyrene-actin assays by 80%, explaining why there are still more filaments in Smy1 + Bnr1 reactions than in actin/profilin control reactions.

Next, we tested whether Smy1 can displace Bnr1 (FH2) from the growing barbed ends of actin filaments as previously shown for Bud14 (Chesarone et al., 2009). For these tests, we employed a 'seeded' elongation assay in which mechanically sheared filaments are mixed with yeast capping protein (CP) (0.5µM) and/or Bnr1 (0.7 nM), and then added to pyrene-actin monomers (0.5 µM) to monitor polymerization at the barbed ends of filament seeds. As expected, CP alone terminated barbed end growth, while Bnr1 protected barbed end growth from CP (Figure 1, E). Consistent with our previous results, addition of Bud14 at any point during the reaction reversed the ability of Bnr1 to protect barbed ends from CP, indicative of Bnr1 displacement from the growing barbed ends (Figure 1, E). In contrast, Smy1 addition had no effect on the activities of Bnr1 and/or CP (Figure 1, E, control reactions shown in Supplementary Figure 1, E and G). Thus, Smy1 lacks formin displacement activity and is functionally distinct from Bud14.

Profilin is an actin monomer binding protein that plays a critical role in formin-mediated actin filament elongation both in vitro and in vivo (Kovar et al., 2006; Kovar and Pollard, 2004a; Sagot et al., 2002b; Yonetani et al., 2008). Further, most of the actin monomer pool in vivo is believed to be associated with profilin (Kaiser et al., 1999). Therefore, we tested Smy1 effects on seeded elongation in the presence of profilin. Again under these conditions, Bnr1 protected growing barbed ends from CP (Figure 1, F), and Bud14 reversed Bnr1 effects, while Smy1 did not (Figure 1, F). On the other hand, specifically in the presence of profilin Smy1 caused a modest but reproducible decrease in the rate of filament elongation either with or without CP (Figure 1, F and Supplementary Figure 1, F). Notably, Smy1 had no effect on filament elongation in the absence of Bnr1 (Supplementary Figure 1, G). This ability of Smy1 to reduce the rate of elongation in the presence of Bnr1 was not observed above in the absence of profilin (Figure 1, E). Thus, it is possible that Smy1 association with the FH2 domain of Bnr1 partially blocks insertion of bulkier profilin-actin complexes (as opposed to actin alone) at Bnr1-capped barbed ends, slowing the rate of filament elongation.

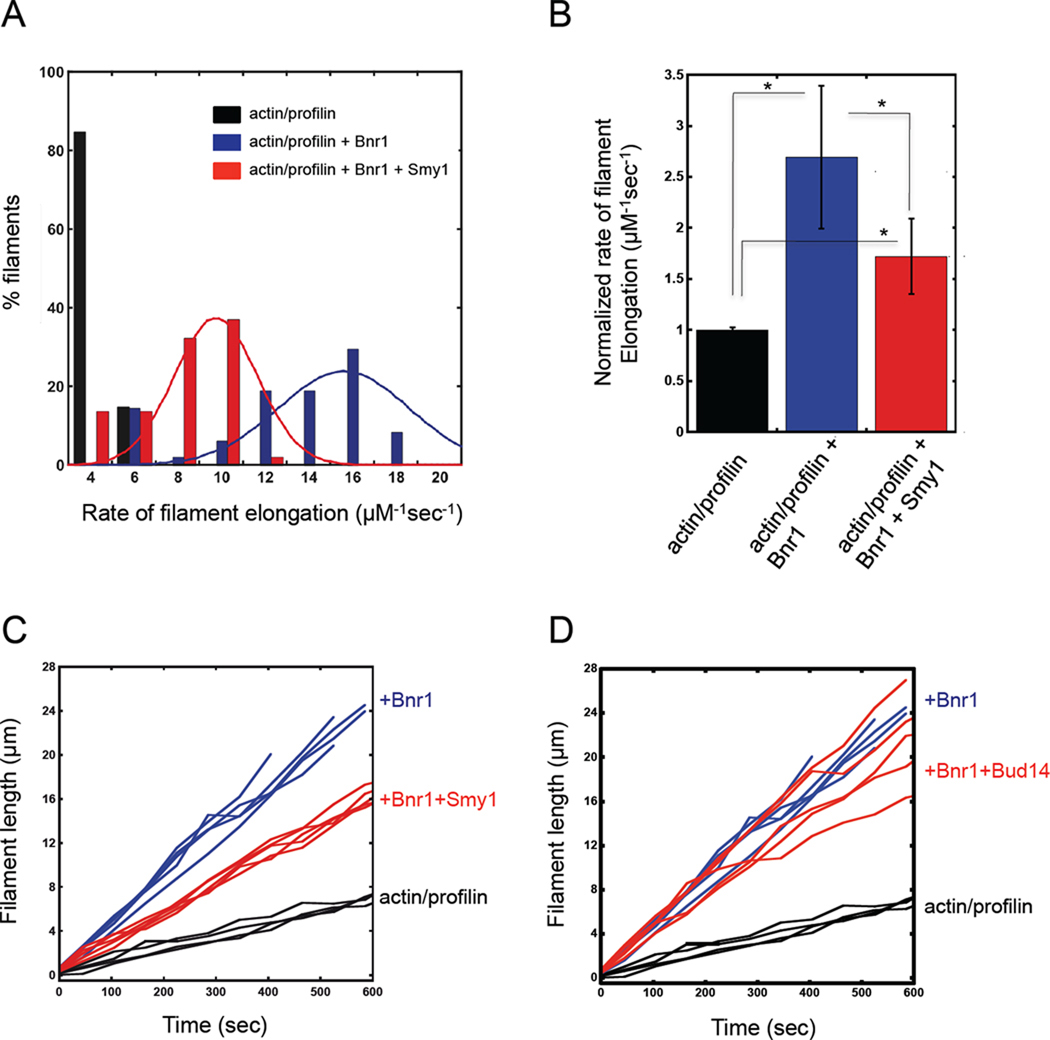

Smy1 slows the rate of elongation of Bnr1-capped actin filaments

Some aspects of actin dynamics including rates of elongation are better studied at the single filament level rather than in bulk assays (Kovar and Pollard, 2004b). Therefore, to further explore the effects of Smy1 on Bnr1-mediated filament elongation, we employed TIRF microscopy. Rates of elongation for individual filaments were determined by dividing filament length gained over the course of a reaction by the time of the reaction. Bnr1 accelerated the rate of filament barbed end growth in the presence of profilin, as shown by a dramatic shift in the distribution of filament elongation rates (Figure 2, A, blue bars) and a 2.7-fold increase in the average rate of elongation (Figure 2, B). This ~ 2.7-fold increase in elongation rate falls well within the range of effects by other formins, and is similar to the reported 2-fold increase by Bni1 (Kovar et al., 2006). Upon further addition of Smy1, the distribution of filament elongation rates shifted toward slower speeds (Figure 2, A, red bars), with an average rate of elongation half way between the rates for Bnr1-capped filaments and filaments with free barbed ends (Figure 2, B). These data suggest that when Smy1 associates with the FH2 domain of Bnr1, it dampens the formin’s elongation activity. This effect of Smy1 in slowing elongation by Bnr1 was more pronounced here by TIRF than in the bulk assays above. Note that bulk pyrene-actin assays fail to detect the effects of Bnr1 in accelerating elongation in the presence of profilin (see Supplementary Figure 1, E and G, for control curves), as documented previously (Moseley and Goode, 2005). This has been suggested to be due to the reduced affinity of profilin for pyrene-actin (Vinson et al., 1998).

Figure 2. Smy1 slows the elongation of Bnr1-capped actin filaments.

TIRF microscopy was used to directly measure the elongation rates of filaments assembled from 1µM actin and 3µM profilin in the presence of the indicated proteins or control buffer. (A) Rate of elongation was determined by measuring the distance each filament barbed end elongated during the observation window (600 s). Filaments were grown in the presence of control buffer, 1nM Bnr1, or 1nM Bnr1+500nM Smy1 (421–577). Solid lines correspond to Gaussian fits of the data. (B) Average rate of elongation for each condition was normalized to actin alone (set at one). * = p ≤ 0.0001 as measured by student's t-test. (C, D) Lengths of individual filaments graphed as a function of time during the reactions. Five representative filaments for each condition are shown.

(C) Note that for actin alone, 1nM Bnr1 alone, and 1nM Bnr1+500nM Smy1 (421–577), each filament grew at a steady velocity (indicated by the slope of the line). (D) For 1nM Bnr1 + 500nM Bud14 (179–472), the velocity of filament growth was observed to change abruptly, consistent with Bnr1 displacement by Bud14 (transition from faster to slower growth) and re-association of free Bnr1 (transition from slower to faster growth).

To better understand Smy1’s effects in dampening filament elongation rates, we also tracked filament lengths over time during the reactions. Monitoring filament lengths in real time allows detection of major fluctuations in rates of elongation that might occur. This analysis showed that Bnr1-capped filaments elongated at a steady rate throughout the 10 minutes observation window, and in the presence of Smy1 and Bnr1 filaments grew at a constant but slower rate (Figure 2, C). In contrast, combining Bud14 and Bnr1 led to abrupt changes in the filament elongation rate. This behavior was consistent with transitions from fast-growing Bnr1-capped ends to displacement of Bnr1 by Bud14, reducing the elongation rate to that of free barbed ends (Figure 2, D). Note, it was not possible to test higher concentrations of Bud14 or Smy1 in these assays because they block nucleation by Bnr1.

These observations highlight the functional and mechanistic differences between Smy1 and Bud14. While Bud14 abruptly displaces Bnr1 from filament ends and thereby terminates formin-mediated actin assembly events, Smy1 instead had a constant dampening effect on the rate of elongation without displacing Bnr1.

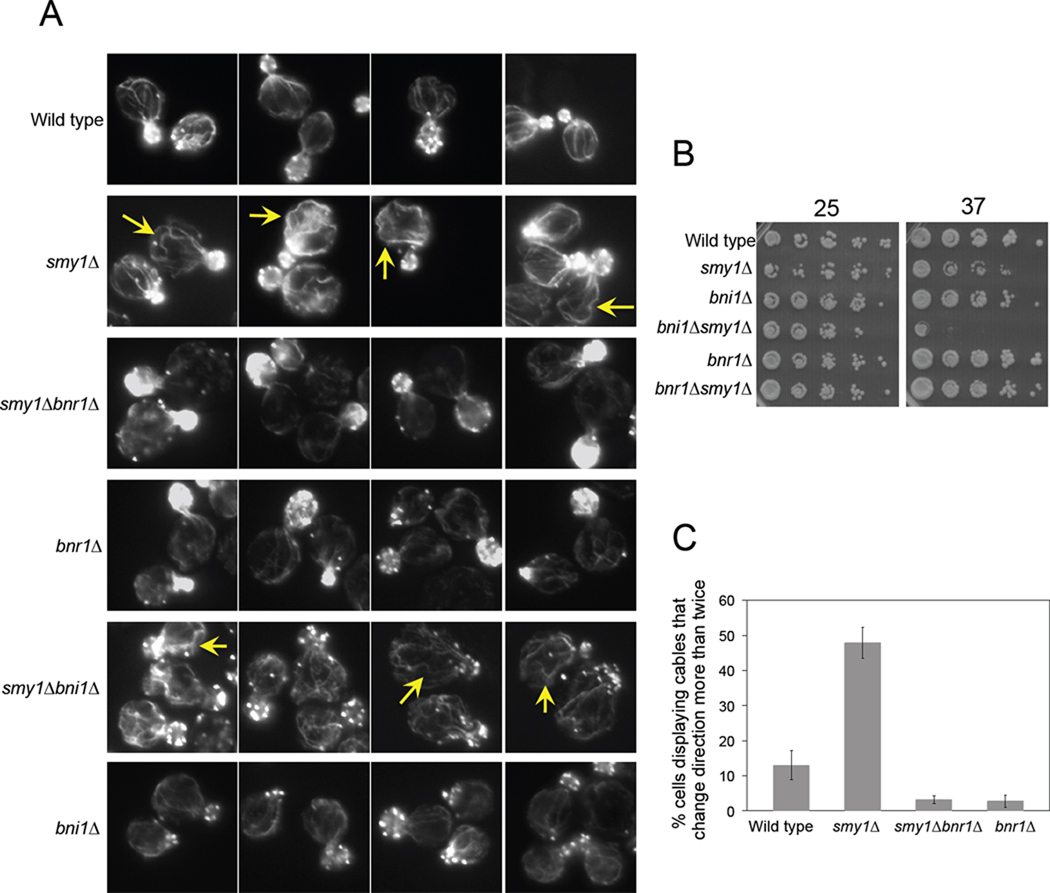

Loss of Smy1 in vivo causes acute defects in Bnr1-generated actin cables

We next sought to understand how these activities of Smy1 contribute to regulation of Bnr1 in vivo. As a first step, we deleted the SMY1 gene and carefully examined cellular actin organization in fixed cells by staining with Alexa-488 phalloidin. This analysis revealed that smy1Δ caused strong defects in actin cable architecture in the mother cells. Mutant cables were both abnormally long and 'curvilinear', changing direction sharply and multiple times, producing a 'wavy' appearance with thicker and thinner segments (Figure 3, A, yellow arrows). These cable defects were suppressed by the deletion of BNR1, supporting the view that they arise from misregulation of Bnr1 activity in the absence of Smy1 (Figure 3, A and C). We also examined smy1Δ cable defects in the bni1Δ background, where Bnr1 is the only formin expressed. In smy1Δbni1Δ cells, the smy1Δ cable phenotype was even more apparent (Figure 3, A), possibly since Bni1-generated cables with normal architecture are now absent. Further, this strain showed temperature sensitive growth defects (Figure 3, B), suggesting that when Bnr1 is the only formin remaining, Smy1 activity is critical for formation of actin cables with normal architecture and function. In contrast, smy1Δbnr1Δ cells showed actin cable staining indistinguishable from bnr1Δ cells, consistent with the view that Smy1 specifically regulates Bnr1 and not Bni1.

Figure 3. smy1Δ causes Bnr1-dependent defects in actin cable architecture.

(A) Representative images of the indicated strains, fixed and stained with Alexa-488 phalloidin. Note the actin cable defects in smy1Δ (yellow arrows), which are suppressed in smy1Δbnr1Δ, whereas compounded defects in actin organization were observed in smy1Δbni1Δ. (B) The indicated yeast strains were serially diluted and compared for growth on YPD medium at 25°C and 37°C. (C) Quantification of "wavy" cable phenotype (cables that changed direction in the mother more than twice), n > 100 cells.

Note, bnr1Δ actually suppressed the slight temperature sensitive growth defects of smy1Δ (Figure 3, B), demonstrating that misregulation of Bnr1 activity due to the absence of Smy1 is more detrimental than loss of Bnr1 activity. These data suggest that smy1Δ cable defects are a gain of function phenotype resulting from unregulated Bnr1 activity.

To address the possibility that the observed growth defects might be correlated with a reduction in cable number, rather than abnormalities in cable architecture, we also quantified cable number in the mother cells of each strain (Table S1). This analysis showed that smy1Δ did not significantly reduce the cable number in strains expressing either or both formins (Bni1 and Bnr1), and therefore the observed growth defects in mutants correlated with the appearance of aberrant cable structure rather than a reduction in cable number. These observations suggest that proper cable architecture is more important for maintaining polarized cell growth than the overall number of cables.

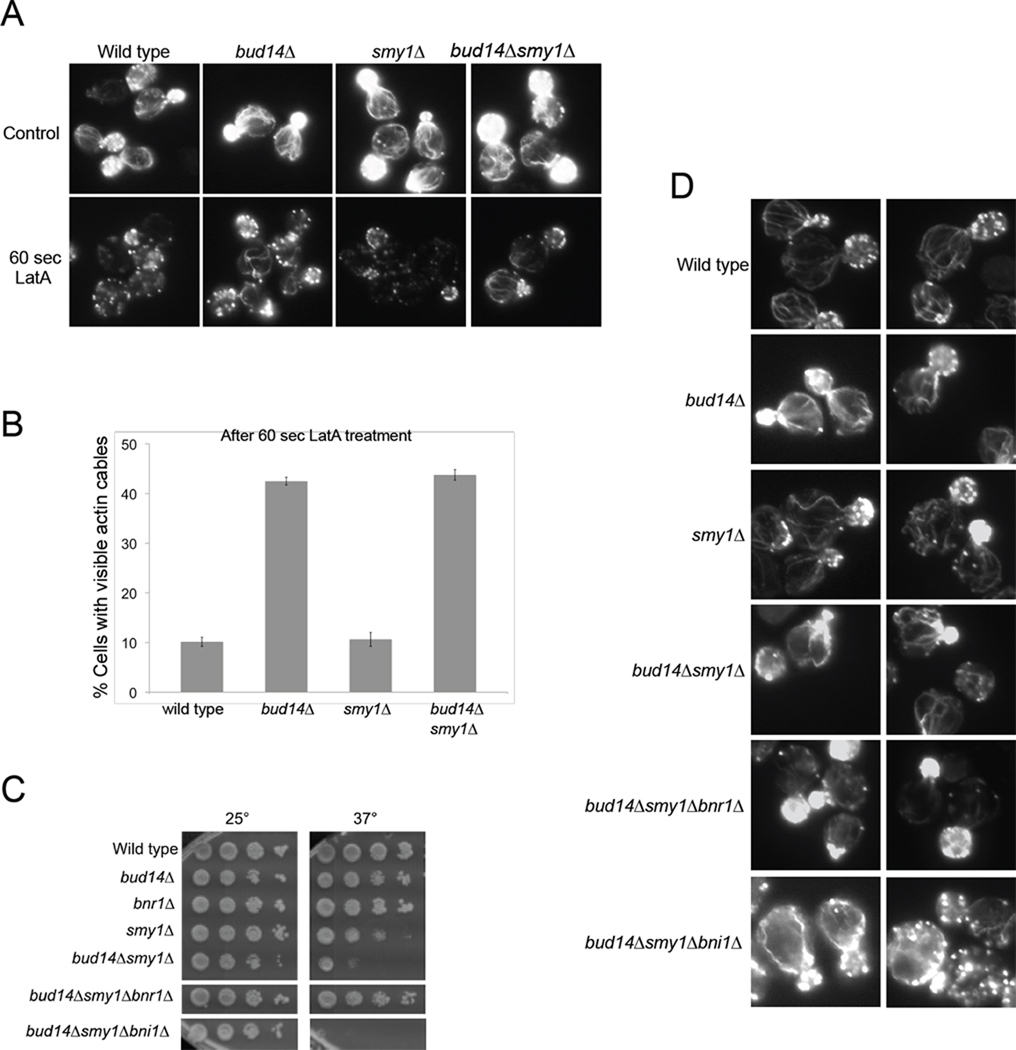

SMY1 and BUD14 have separate genetic functions in actin cable assembly

Bud14 is the only other known direct regulator of Bnr1 activity. Although the actin cables in smy1Δ and bud14Δ cells are both ‘overgrown’, they have highly distinct architectures. The smy1Δ cells have wavy cables of uneven thickness, whereas bud14Δ cells have smoother cables of more uniform thickness, which typically buckle where they hit the cortex. The bud14Δ cables are resistant to a brief treatment of cells with Latrunculin A (LatA) (Chesarone et al., 2009), consistent with loss of formin displacement activity, which is predicted to increase the length of actin filaments in the cables compared to wild type cells. In contrast, actin cables in smy1Δ cells were not resistant to LatA (Figure 4, A and B). These observations are consistent with the differences in biochemical activities we observe for Smy1 and Bud14 (Figures 1 and 2), and reinforce the point that actin cable defects in smy1Δ and bud14Δ cells are fundamentally different.

Figure 4. Genetic evidence that SMY1 and BUD14 perform distinct functions in regulating BNR1.

(A) Representative cells for wild type, bud14Δ, smy1Δ and bud14Δsmy1Δ strains treated with 20µM LatA or control buffer for 60 s, fixed and stained with Alexa 488 phalloidin. Note the LatA resistant actin cables in bud14Δ and bud14Δsmy1Δ cells. (B) Data quantified from at least two independent experiments as in A, n > 100 cells. (C) Yeast strains were serially diluted and compared for growth on YPD medium at 25°C and 37°C. (D) Representative images of the indicated strains grown at 25°C, fixed and stained with Alexa-488 phalloidin.

We also generated a bud14Δsmy1Δ double mutant strain to test whether the smy1Δ phenotype is dependent on BUD14, or vice versa. Double mutant cells displayed a temperature sensitive growth defect more severe than either single mutant, which was further compounded by bni1Δ (Figure 4, C). These synthetic defects indicate that Smy1 and Bud14 each make separate contributions to Bnr1 regulation. Remarkably, the growth defects of bud14Δsmy1Δ were completely suppressed in a bud14Δsmy1Δbnr1Δ triple mutant, demonstrating that SMY1 and BUD14 function upstream of BNR1, and that the impaired viability of the bud14Δsmy1Δ cells likely arises from misregulation of Bnr1 activity (Figure 4, C).

Interestingly, bud14Δsmy1Δ cells displayed abnormally long cables, some of which were smooth and LatA resistant (bud14Δ-like) and some of which were wavy (smy1Δ-like) (Figure 4, A and D). Further, all of the cable defects were suppressed in bud14Δsmy1Δbnr1Δ cells (Figure 4, D). In contrast, bud14Δsmy1Δbni1Δ cells exhibited very severe defects in cable architecture with highly depolarized actin patches, suggesting a dramatic loss of cell polarity due to the combined loss of Bni1-generated actin cables and the assembly by Bnr1 of only partially-functional cables (Figure 4, D). It is again important to note that although both strains showed decreased numbers of actin cables compared to wild type (Table S1), only the bud14Δsmy1Δbni1Δ displayed synthetic growth defects, indicating that the enhanced growth defects are primarily due to aberrant cable architecture rather than reduced cable levels. Thus, Bni1 generates a set of functional cables that become critical for maintaining polarity when Bnr1 is misregulated by bud14Δsmy1Δ. Together, these data suggest that Smy1 and Bud14 make distinct and independent contributions to regulating Bnr1-mediated actin cable assembly in vivo.

SMY1 is required to maintain normal speeds of actin cable extension in vivo

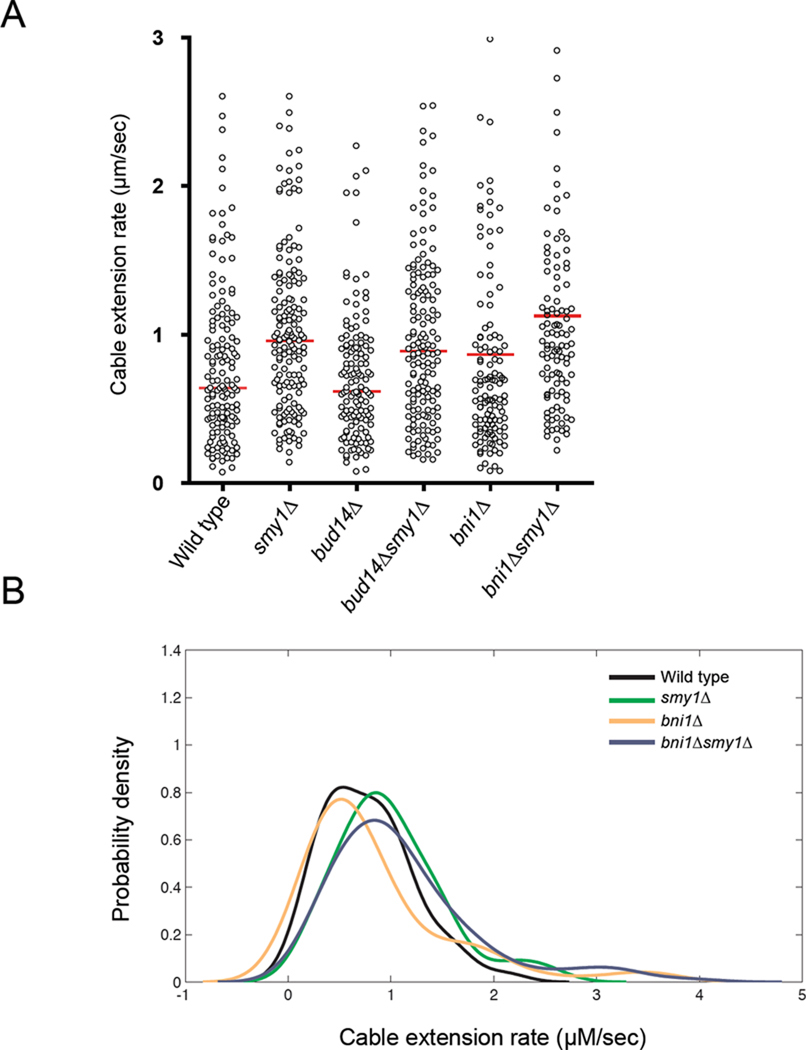

Actin cables generated by Bnr1 extend from the bud neck into the mother cell at rates of approximately 0.5–1µm/sec (Huckaba et al., 2006; Yang and Pon, 2002; Yu et al., 2011). Given the biochemical effects we observed for Smy1 in slowing elongation of Bnr1-capped filaments, we asked whether smy1Δ altered rates of actin cable extension in vivo. To address this, we introduced an endogenously tagged cable marker (Abp140-GFP) and employed a newly described method for quantitatively measuring cable extension rates in vivo by TIRF microscopy (Yu et al., 2011). The majority of actin cables in yeast contour the cell cortex, enabling their dynamics to be monitored by TIRF microscopy (Amberg, 1998; Yu et al., 2011). We compared the dynamics of individual actin cables in wild type, smy1Δ, bud14Δ, smy1Δbud14Δ, bni1Δ and smy1Δbni1Δ cells (Figure 5, A). As recently described (Yu et al., 2011), there are at least two distinct kinetic populations of cables in wild type mother cells: those assembled by Bnr1 at the bud neck, which have average extension speeds < 1 µm/s, and those assembled by cortical Bni1 in the bud, which extend at speeds of 1–2 µm/s (Figure 5, A; and (Yu et al., 2011)).

Figure 5. smy1Δ increases rates of actin cable extension in vivo.

TIRF microscopy was used to image live yeast cells expressing Abp140-GFP, a marker for actin cables, and to track extension of actin cables near the cortex in mother cells. Rates of actin cable extension were determined by calculating the distance that the end of a cable extended over time. (A) Scatter plots show the extension rates of each actin cable measured in the indicated strains. Red bars indicate the average rates. (B) Probability density analysis was used to estimate the relative likelihood that cables extend at a given velocity, as described in Materials and Methods. The data for two strains (bud14Δ and smy1Δbud14Δ) were removed from this graph for simplicity, but are reported in Supplementary Figure 2. Note the marked depletion of the slowest subset of cable velocities in smy1Δ versus wild type, and in bni1Δsmy1Δ versus bni1Δ. This suggests that Smy1 is required in cells to maintain the slowest subset of cables.

Since Smy1 slows the rate of Bnr1-mediated actin filament elongation in vitro, smy1Δ cells would be predicted to display an increase in average cable extension velocity and/or a shift in the distribution of cable velocities (if Smy1 affects only a particular subset of cables in vivo). Our analysis showed that in smy1Δ cells, there was a faster average cable extension rate compared to wild type or bud14Δ cells (Figure 5, A and Supplementary Figure 2, B). The same trend was observed in smy1Δ cells lacking Bni1 (smy1Δbni1Δ), verifying that these effects were via Smy1 influence on Bnr1 (Figure 5, A). Further, deletion of SMY1 markedly changed the cable velocity distribution, reducing the number of cables elongating at velocities < 0.5 µm/s (i.e. the slowest extending cables)(scatter plot; Figure 5, A). This was further supported by a probability analysis of the data, which revealed a shift in the cable velocity distribution (toward faster rates) for cables in smy1Δ versus wild type and in smy1Δbni1Δ versus bni1Δ cells (Figure 5, B and Supplementary Figure 2, A). Because smy1Δ does not affect Bnr1-GFP localization to the neck (Supplementary Figure 2, C), these data suggest that the faster cable velocities in smy1Δ strains result from mis-regulation of Bnr1 activity. Since bud14Δ had wild type rates of cable extension, this suggests that Smy1 can still regulate Bnr1 in cells lacking Bud14.

Smy1 particles are trafficked by myosin V to sites of actin cable assembly

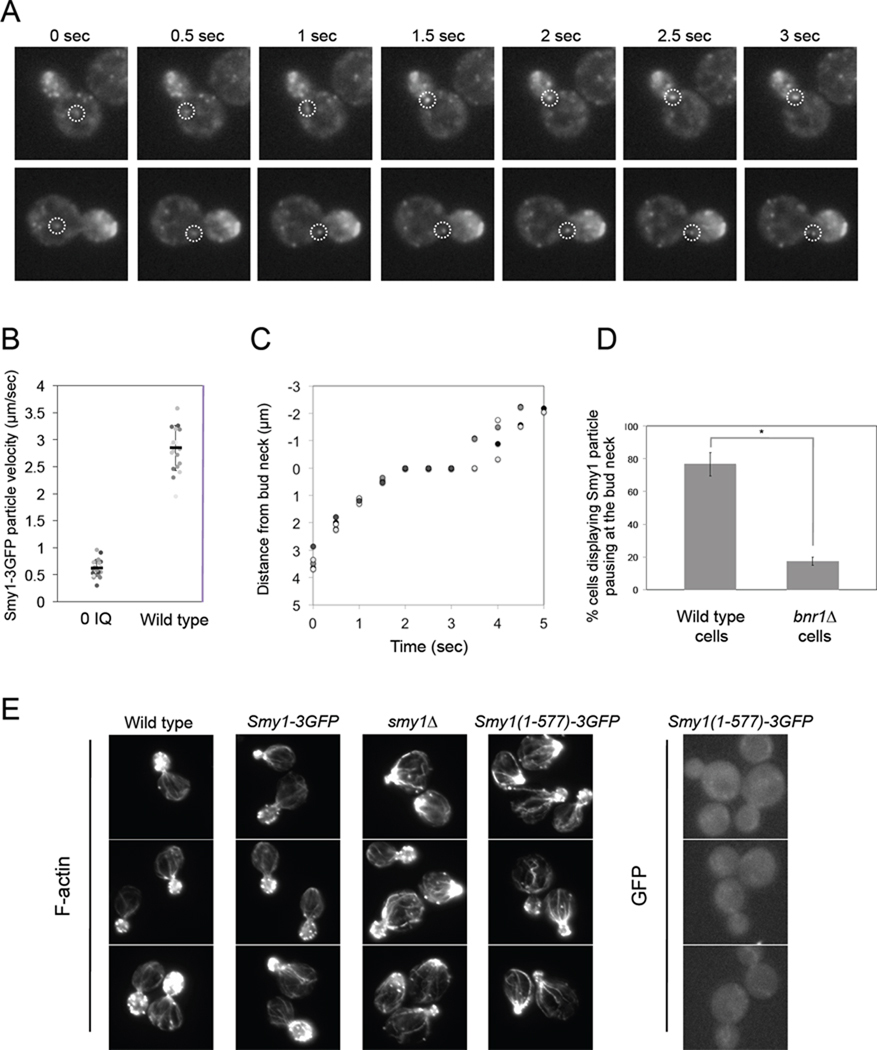

All detectable Bnr1-GFP fluorescence in cells is confined to the bud neck and shows no exchange with the cytoplasm for periods of > 20 minutes by FRAP analysis (Buttery et al., 2007). This suggests that Bnr1 molecules are stably anchored at the neck. Since Smy1 localizes predominantly to the bud tip rather than neck (Lillie and Brown, 1994), we asked when/where in cells does Smy1 interact with Bnr1 to regulate cable assembly? One recent study showed that Smy1-GFP co-localizes with Sec4-GFP (Hodges et al., 2009), suggesting that Smy1 is a component of the fast-moving secretory vesicles, which are trafficked through the bud neck by myosin V (Myo2). To investigate this further, we generated a functional, triple GFP-tagged Smy1 (Smy1–3GFP) for live-cell imaging which was integrated into the genome at the endogenous SMY1 locus and expressed under the control of its own promoter. Importantly, this allele complemented SMY1 function, as the appearance of actin cables in the SMY1–3GFP strain was indistinguishable from wild type (Figure 6, E).

Figure 6. Tracking of Smy1–3GFP particle movements in living cells.

(A) In wild type cells, Smy1–3GFP particles moved rapidly through the mother cell and paused at the bud neck. Shown are representative grayscale, time-lapse series for two particles tracked. (B) Scatter plot of Smy1–3GFP particle velocities in myo2-0IQ and wild type strains. Black bars represent mean velocities for each strain, and error bars represent SD. The individual data points have been labeled different shades of gray for clarity. (C) Graph of the distance of individual Smy1–3GFP particles from the bud neck versus time, measured during the course of a 4 s movie. Each of the particles tracked is labeled in a different shade of gray for clarity. Positive numbers indicate movement from the mother compartment towards the bud neck, and negative numbers indicate movement away from the bud neck, into the bud compartment. (D) Quantification of the frequency of Smy1–3GFP particle pausing at the bud neck in both wild type and bnr1Δ, scored as the percent of cells exhibiting at least one Smy1–3GFP particle "pause" at the bud neck during a 30 s observation period. A pause was defined as any particle that remained at the bud neck for >1.5 s. * = p < .0002, as measured be the student's t test. (E) Strains were grown at 25°C to log phase, fixed and either stained with Alex-488 phalloidin to visualize F-actin or directly imaged for GFP signal.

Consistent with previous studies showing that Smy1 accumulation at the bud tip requires Myo2 (Beningo et al., 2000; Hodges et al., 2009; Lillie and Brown, 1994), we observed fast moving Smy1–3GFP particles traveling directionally towards the bud tip (Figure 6, A). To test whether these movements were dependent on Myo2 motor activity, we compared Smy1–3GFP particle speeds in wild type cells and cells expressing a mutant Myo2 with reduced in vivo motility (myo2-0IQ) (Schott et al., 2002). Particles moved approximately 5-fold slower in myo2-0IQ cells compared to wild type cells (Figure 6, B), indicating that indeed Smy1 is trafficked by Myo2 on actin cables.

Interestingly, Smy1–3GFP particles also 'paused' as they traversed the bud neck, which was similarly reported for Smy1-GFP (Hodges et al., 2009) (Figure 6, A, C and D). These pauses occurred concomitantly with particles reaching the bud neck (Figure 6, C), and lasted approximately 1–2 seconds. Subsequently, Smy1–3GFP particles left the neck area and underwent directed movements towards the bud tip (Figure 6, C and Supplementary Figure 3). To test whether pausing of Smy1–3GFP particles at the neck was dependent on Bnr1, we compared particle dynamics in wild type and bnr1Δ cells. The percentage of cells displaying Smy1–3GFP pausing at the neck was dramatically reduced in bnr1Δ compared to wild type (Figure 6, D), demonstrating that pausing depends on Bnr1. Collectively, these observations suggest that Smy1 particles are rapidly transported by Myo2 on actin cables to the bud neck, where they may interact with Bnr1 for 1–2 seconds at a time to slow cable elongation, serving as transient inhibitory cues.

To test whether Myo2 delivery of Smy1 particles is necessary for Smy1 regulation of Bnr1-mediated actin cable assembly, we also generated an allele of smy1 lacking residues 578–657 (Smy1 (1–577)-3GFP). This deletion has previously been shown to disrupt Smy1 association with Myo2, and block the accumulation of Smy1 at polarity sites (Beningo et al., 2000). Consistent with these results, we found that Smy1 (1–577)-3GFP no longer localized to dynamic particles but was instead diffusely cytosolic (Figure 6, E). Further, the truncation mutant showed actin cable defects indistinguishable from those in smy1Δ cells (Figure 6, E), suggesting that transport by Myo2 is required for Smy1 function in regulating Bnr1-mediated actin cable formation. However, it should also be noted that purified Smy1(1–577) is impaired 2-fold in Bnr1 inhibition in vitro compared to full-length Smy1 (Figure 1, C). Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that this small loss of activity also contributes to the observed cable defects.

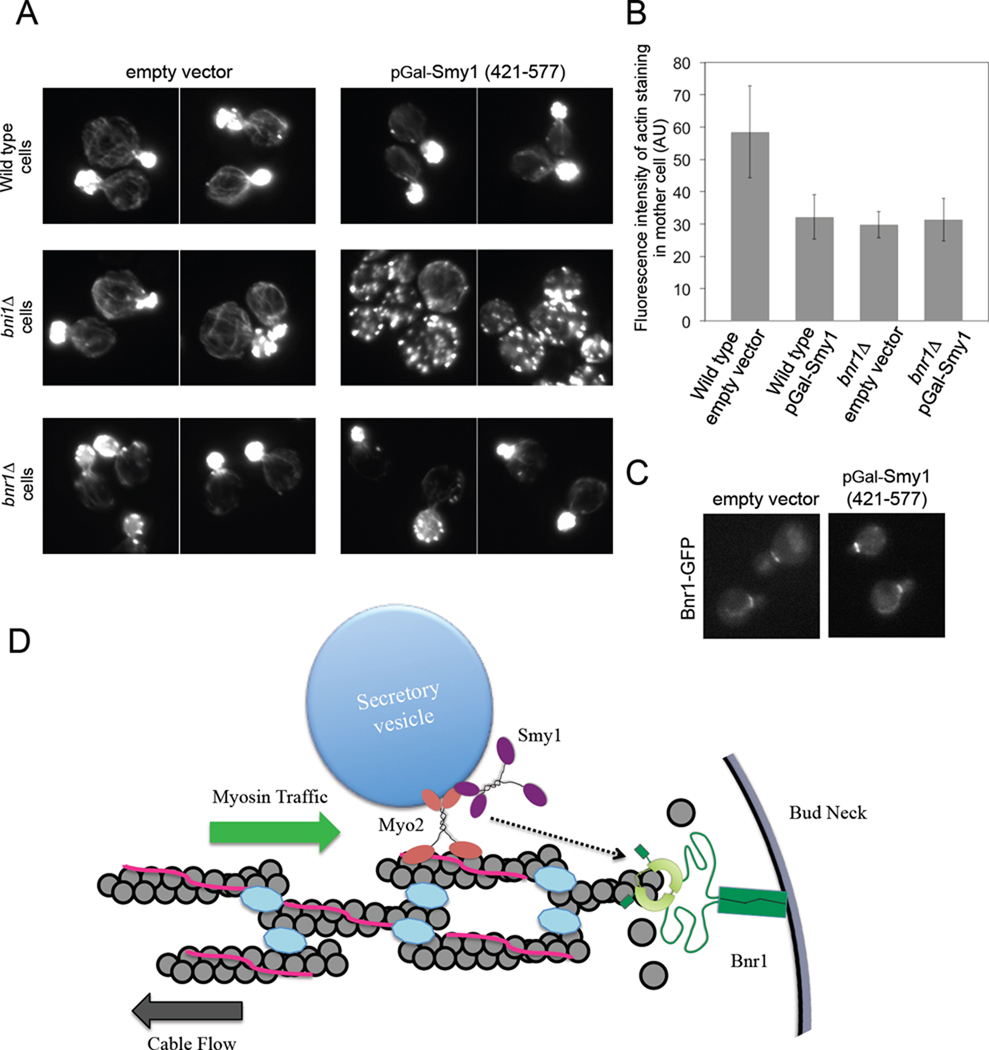

Our data suggest that the ability of endogenous Smy1 to regulate Bnr1 activity may be spatially and temporally controlled in vivo, requiring delivery on secretory vesicles by Myo2. This mechanism likely provides insurance that Smy1 inhibitory cues are used appropriately to slow cable elongation, and to prevent Smy1 from more generally inhibiting actin nucleation by Bnr1. This led us to ask whether over-expression of the inhibitory fragment of Smy1 (421–577) alone under control of the GAL promoter could block the formation of actin cables by Bnr1. Indeed, Smy1 (421–577) over-expression in wild type cells caused a decrease in actin cable staining in the mother cells (Figure 7, A and B), consistent with loss of Bnr1 function. This effect was even more evident in the bni1Δ background, where Smy1 (421–577) over-expression caused a loss of virtually all cable staining and severe depolarization of actin patches (Figure 7, A). Because the actin patches in these cells are so highly depolarized and therefore were present in mother cells, it was not possible to use quantification of F-actin intensity to score cable loss as above. Instead, we manually scored percent cells with visible actin cables in the mother. Smy1 (421–577) over-expression led to only 25% of bni1Δ cells showing visible cables (compared to 100% in cells with empty vector). As expected, Smy1 (421–577) over-expression in bnr1Δ cells caused no detectable loss of cable staining compared to empty vector (Figure 7, A and B). Since Smy1 overexpression did not affect localization of Bnr1-GFP, this suggested that loss of cables was due to Smy1 inhibition of Bnr1 activity (Figure 7, C). Over-expression of a slightly larger fragment of Smy1 (421–657) containing the Myo2-binding domain had similar effects (Supplementary Figure 4, A and B). Together, these data show that elevated levels of Smy1 cause potent inhibition of Bnr1 activity in vivo, phenocopying bnr1Δ.

Figure 7. Over-expression of Smy1 (421–577) inhibits Bnr1-mediated actin cable assembly.

(A) Actin organization defects caused by GAL-over-expression of Smy1 (421–577) in wild type, bni1Δ and bnr1Δ strains. Cells were induced with galactose overnight, fixed, and stained with Alexa-488 phalloidin. (B) To quantify the effects of Smy1 (421–577) over-expression on wild type and bnr1Δ actin cables, we measured the intensity of Alexa-488 phalloidin staining in the mother cell for the indicated strains. (C) Localization of Bnr1-GFP to the neck was unaffected by over-expression of Smy1 (421–577). (D) A model for Smy1 regulation of Bnr1-mediated actin cable assembly. Bnr1 (green) is tethered to the bud neck and polymerizes actin filaments that are incorporated into extending cables. The filaments in cables become decorated with tropomyosin (pink) and bundling proteins (turquoise), which maintain filament organization and stability. Myosin-V (Myo2 in yeast, red) rapidly transports secretory vesicles and Smy1 (purple) on actin cables to the bud neck, where Smy1 transiently interacts with Bnr1 to reduce the speed of actin cable extension and prevent cable overgrowth

Discussion

We have shown that Smy1 inhibits the actin nucleation and elongation activities of Bnr1 in vitro, and loss of SMY1 in vivo results in severe defects in Bnr1-dependent actin cable architecture and dynamics. Notably, the specific cable defects in smy1Δ cells are distinct from those in bud14Δ cells. Further, we have demonstrated that Smy1 and Bud14 have biochemically and genetically distinct effects on Bnr1 activity. Whereas Bud14 disrupts interactions of Bnr1 with the barbed end to control filament length, Smy1 lacks displacement activity and instead controls the speed of filament elongation by Bnr1. This mode of formin regulation represents a cellular mechanism for controlling actin network dynamics and organization.

Bridling formins to control actin network assembly in vivo

Our findings underscore the importance of tightly restraining formin activities to prevent gain-of-function phenotypes. Loss of BNR1 causes only a subtle phenotype and does not affect cell viability, because the other formin, Bni1, makes a complementary set of cables that support polarized cell growth. However, a smy1Δbud14Δ double mutation causes severe Bnr1-dependent defects in cell polarity and growth (Figure 4, C and D). This demonstrates that misregulated Bnr1 activity, leading to abnormal cable growth, architecture, and dynamics, is far more detrimental to cells than the complete loss of Bnr1. Notably, it is the over-expression, not the deletion, of formins that is linked to lymphoid malignances and colorectal cancer in humans (Favaro et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2008). Further, single copies of hyper-activated alleles of the formin INF2 cause gain of function phenotypes leading to kidney disease (Brown et al., 2010). These observations suggest that unbridled formin activity (as opposed to loss of formin activity) can produce severe cellular abnormalities in a variety of contexts, and stresses the importance of understanding the mechanisms for spatially and temporally restricting formin activities in vivo.

Smy1 mechanism of slowing elongation of Bnr1-capped actin filaments

Our biochemical data suggest that by associating with the FH2 domain of Bnr1, Smy1 slows the rate of elongation of Bnr1-capped filaments. Through TIRF microscopy analysis, we observed that Bnr1, like other formins, increases the average rate of barbed end filament elongation (2.7-fold) (Figure 2, A and B). However, in the presence of Bnr1 and Smy1, filaments elongated at a slower, steady rate, intermediate between Bnr1 alone and the actin/profilin control (Figure 2, A and C). If Smy1 displaced Bnr1 from barbed ends, we would expect to see filaments in the population growing at two different rates, one corresponding to Bnr1 alone, and one corresponding to actin/profilin. Further, in time-lapse experiments, one would expect to observe abrupt transitions between these two rates when displacement events occurred. This is exactly the behavior we observed for Bud14 with Bnr1, but not Smy1 with Bnr1 (Figure 2, C and D).

We suggest that Smy1 associates with Bnr1 on the filament end and acts as a brake or ‘damper’ to reduce the rates of profilin-actin subunit insertion at the filament end. Alternatively, we cannot rule out the possibility that Smy1 induces Bnr1 to rapidly dissociate and re-associate with filament ends to reduce the average rate of elongation. However, the constant rates of elongation we observed in the presence of Smy1 and Bnr1 favor the first model. Moreover, Smy1 addition did not change the ability of Bnr1 to protect filament ends from CP in seeded elongation assays (Figure 1, E and F). Any displacement of Bnr1 (even if brief) would lead to CP (in vast molar excess) terminating filament growth, which was not observed. Together, these data suggest that Smy1 associates with Bnr1 on the filament end to reduce the speed of elongation.

Our in vivo data also support this function for Smy1. In wild type cells, Bnr1 drives actin cable extension at a wide range of rates with an average velocity < 1 µm/s (Yu et al., 2011). In smy1Δ cells, we observed that cables extended at a higher average velocity, and the distribution was altered, with a marked reduction in the very slow velocities (< 0.5 µm/s) (Figure 5, A and B). This demonstrates that SMY1 is required for maintaining the slower cables in the population. These findings imply that there may be a subset of cables in cells at any given time that are being transiently inhibited by Smy1 to grow at very slow speeds. This may be part of a negative feedback mechanism to sense cable length and prevent cable overgrowth (see below). Our data also show that many cables in smy1Δ cells have a highly abnormal wavy appearance and change thickness and direction multiple times. The connection between the altered architecture and dynamics is not yet clear, but one possibility is that wavy cables are the result of cable overgrowth and buckling. However, we note that smy1Δ and bud14Δ cable defects are highly distinct. In bud14Δ cells, cables are abnormally long and appear to be comprised of longer individual actin filaments, but extend at normal rates. In smy1Δ cells, the overgrown cables appear to be comprised of actin filaments of normal length but extend abnormally fast. Thus, the loss of two distinct formin regulatory activities (displacement versus damper) results in cable overgrowth, but the cables have highly distinct architectures and dynamics. Consistent with this view, smy1Δ and bud14Δ mutations have compounded growth defects and show both cable phenotypes.

Myosin-dependent delivery of Smy1: a negative feedback mechanism for controlling cable length

We have shown that Smy1–3GFP particles are transported by Myo2 on actin cables to the bud neck where they appear to transiently interact with Bnr1 to slow cable elongation (see model; Figure 7, D). Further, a Smy1 mutant lacking the Myo2-binding domain is no longer transported to the neck and gives rise to cable phenotypes similar to smy1Δ. From these data we cannot rule out the possibility that the two-fold loss of inhibitory activity associated with this mutant (Figure 1, C) leads to the cable phenotypes observed. However, since the cable phenotype was as penetrant as the null, and since this mutant showed a complete loss of myosin-dependent transport, we favor the interpretation that myosin-based transport of Smy1 is required for Bnr1 inhibition in vivo. What function might be served by this requirement? Because loss of Smy1 activity in vivo leads to (i) a reduction in the slowest-moving cables and (ii) the appearance of a subset of overgrown cables with buckled architectures, we propose that Smy1 serves as part of a negative feedback loop that senses cable length and prevents overgrowth. Specifically, longer cables would bind more Smy1-Myo2 particles than shorter cables, and thus deliver more Smy1 transient inhibitory cues to Bnr1 at the ends of those cables, slowing their extension rates. Note that Smy1 is about 7-fold more abundant in cells than Bnr1 (Ghaemmaghami et al., 2003). Therefore, Smy1 inhibitory cues would not be limiting, but rather their delivery to the neck. This mechanism would ensure that shorter cables grow at faster rates, while longer cables (closer to the rear of the cell) are attenuated to prevent overgrowth. It is also possible that such a negative feedback loop helps to control cable assembly at the neck and maintain architecture. For instance, transient pulses of Smy1 inhibition may be required to facilitate stitching together of short filaments to generate evenly bundled cables that efficiently contour the cell cortex without bending and kinking. Although these are only two possible models for how Smy1 regulates Bnr1-mediated cable assembly, they are consistent with all of our biochemical and genetic observations. However, future studies will be required to more directly test these and other possible models.

Smy1 homologues in other eukaryotes

Does Smy1 have functional counterparts in other organisms? Through sequence alignment and tree-building methods, Smy1 has been classified as a divergent member of the kinesin-I subfamily (Lawrence et al., 2002). Interestingly, Smy1 has lost its microtubule motor activity, and the motor-like domain is dispensable for its genetic functions in regulating Myo2 (Hodges et al., 2009; Lillie and Brown, 1998). However, like Smy1, the cargo-binding domain of another member of the kinesin-I subfamily, Kif5B (also known as uKHC or KhcU), has reported interactions with type-V myosin (Beningo et al., 2000; Huang et al., 1999). Moreover, these domains of Smy1 and Kif5B share a stretch of sequence homology (468–555 in Smy1; 27% identity over 87 residues) (Beningo et al., 2000). This stretch encompasses the region of Smy1 to which we mapped the formin inhibitory activity. Kif5B has also been linked to intracellular trafficking in a variety of contexts, which has been attributed to its role as a microtubule motor (Cardoso et al., 2009; Gupta et al., 2008; Jaulin et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tanaka et al., 1998). However, the homology shared between Kif5B and Smy1 raises the possibility that it plays additional roles in formin regulation. Further, while we have focused here on yeast actin cables as a model, it is likely that other actin structures assembled by formins (such as filopodial protrusions, stress fibers and cytokinetic rings) have a similar requirement for regulation of actin filament lengths and elongation speeds. Given that Smy1 is a member of a conserved family of proteins, kinesins, and targets the most highly conserved domain found in formins, the FH2, it will be interesting to learn whether related regulatory mechanisms are utilized in other systems.

Materials and Methods

Details on plasmids, strains and cell imaging can be found in Supplemental Materials. Unless noted, all error bars denote SD.

Protein purification

Details on the purification of recombinant wild type and truncated Smy1 proteins can be found in Supplemental Materials. 6His-fusions of Bni1 (FH1-FH2-C) and Bnr1 (FH1-FH2-C) were Gal-over-expressed and purified from S. cerevisiae as described (Moseley et al., 2006). Recombinant Bud14 (179–472) was purified as described (Chesarone et al., 2009). Recombinant Bnr1 (FH2) was a gift from A. Yunus and M. Rosen. Rabbit skeletal muscle actin (RMA) was purified as described (Spudich and Watt, 1971) and gel filtered. Pyrenyliodoacetamide-labeled RMA was generated as described (Higgs and Pollard, 1999; Pollard and Weeds, 1984). Yeast capping protein and profilin were purified as described (Moseley et al., 2004).

Actin assembly kinetics

For actin assembly assays, gel-filtered monomeric RMA (2µM final, 5% pyrene labeled) in G-buffer (10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.2 mM ATP,0.2 mM CaCl2, and 0.2 mM DTT) was converted to Mg-ATP-actin in buffer containing 10µM MgCl2 and 0.4mM EGTA for 2 minutes immediately prior to use in reactions. A total of 45 ml Mg-ATP-actin was mixed with 12 µl of the indicated proteins or control buffer and 3µl of 20X initiation mix (40 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, 1 M KCl) in 60µl reactions. Pyrene signal was monitored at 25°C in a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Photon Technology International, Lawrenceville, NJ) at excitation 365 nm and emission 407 nm. Rates of assembly were calculated from the slopes of the curves at 25–50% polymerization. For elongation assays, 5µl of freshly mechanically sheared F-actin (10 µM) was added to a mixture of the indicated proteins or control buffers, and then immediately mixed with 0.5 mM monomeric actin (10% pyrene labeled) in 60µl reactions and monitored as above.

In vitro TIRF microscopy

Monomeric RMA (1 µM, 30% Alexa-488 labeled final concentration) was first exchanged in buffer containing 10 µM MgCl2 and 0.4 mM EGTA. After 5 minutes, profilin (3 µM final) was added to actin monomers. Where indicated, 1 nM Bnr1, 500 nM Bud14 (179–472) or 500 nM Smy1(421–577) were also included. Protein mixtures were diluted in freshly prepared fluorescence buffer containing 10 mM imidazole-HCl (pH 7.0), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 mM dithiothreitol, 3 mg/ml glucose, 20 µg/ml catalase, 100 mg/ml glucose oxidase and 0.5% methylcellulose to induce actin polymerization. Actin polymerization was imaged at 20 s intervals on an objective-based TIRF microscope (Nikon TE2000E modified by Roper Scientific). Metamorph software (version.6.3r7; Universal Imaging, Media, PA) was used for image acquisition and analysis.

In vivo LatA-induced actin turnover assays

Isogenic wild type, smy1Δ, bud14Δ and bud14Δsmy1Δ strains were grown in 5 ml YPD cultures to log phase, then cells were pelleted, resuspended in 1 ml YPD, and allowed to recover for 30 minutes. At this point, 200 µl cells were incubated at 30°C with control buffer or buffer containing a final concentration of 20 µM Latruncullin A (LatA; a gift from Phil Crews). At 0 and 60 s, cells were fixed, stained with Alexa-488-phalloidin, imaged as above, and scored for visible actin cables (n>200 cells per sample) as described (Okada et al., 2006).

Overexpression analysis in yeast

Plasmids expressing Smy1 fragments under control of the GAL promoter were transformed into wild type, bni1Δ, bnr1Δ and BNR1-GFP strains. Cell cultures were grown to log phase in selective media containing raffinose, then switched to galactose-containing media, and grown for 24 hr at 25°C. Samples were removed at time zero (at media switch) and 24 hr post-galactose induction, fixed, stained with Alexa488-phalloidin, and imaged as above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Pellman, M. Gupta, S. Yoshida and A. Bretscher for strains and plasmids, and A. Asgar Yunus and M. Rosen for sharing purified Bnr1 (FH2). We thank F. Chang for suggesting that Smy1 may be part of a feedback mechanism for contrlling actin cable length. This work was supported by grants from Agence National pour la Recherche (ANR-08-BLAN-0012) to L.B., and NIH (GM083137) to B.G.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amberg DC. Three-dimensional imaging of the yeast actin cytoskeleton through the budding cell cycle. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3259–3262. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beningo KA, Lillie SH, Brown SS. The yeast kinesin-related protein Smy1p exerts its effects on the class V myosin Myo2p via a physical interaction. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:691–702. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Schlondorff JS, Becker DJ, Tsukaguchi H, Tonna SJ, Uscinski AL, Higgs HN, Henderson JM, Pollak MR. Mutations in the formin gene INF2 cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:72–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttery SM, Yoshida S, Pellman D. Yeast formins Bni1 and Bnr1 utilize different modes of cortical interaction during the assembly of actin cables. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1826–1838. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso CM, Groth-Pedersen L, Hoyer-Hansen M, Kirkegaard T, Corcelle E, Andersen JS, Jaattela M, Nylandsted J. Depletion of kinesin 5B affects lysosomal distribution and stability and induces peri-nuclear accumulation of autophagosomes in cancer cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesarone M, Gould CJ, Moseley JB, Goode BL. Displacement of formins from growing barbed ends by bud14 is critical for actin cable architecture and function. Dev Cell. 2009;16:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesarone MA, DuPage AG, Goode BL. Unleashing formins to remodel the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:62–74. doi: 10.1038/nrm2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesarone MA, Goode BL. Actin nucleation and elongation factors: mechanisms and interplay. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra ES, Higgs HN. The many faces of actin: matching assembly factors with cellular structures. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1110–1121. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista M, Pruyne D, Amberg DC, Boone C, Bretscher A. Formins direct Arp2/3-independent actin filament assembly to polarize cell growth in yeast. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:32–41. doi: 10.1038/ncb718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro PM, de Souza Medina S, Traina F, Basseres DS, Costa FF, Saad ST. Human leukocyte formin: a novel protein expressed in lymphoid malignancies and associated with Akt. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O'Shea EK, Weissman JS. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode BL, Eck MJ. Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:593–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Palmer KJ, Spence P, Hudson A, Stephens DJ. Kinesin-1 (uKHC/KIF5B) is required for bidirectional motility of ER exit sites and efficient ER-to-Golgi transport. Traffic. 2008;9:1850–1866. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Regulation of actin polymerization by Arp2/3 complex and WASp/Scar proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32531–32534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges AR, Bookwalter CS, Krementsova EB, Trybus KM. A nonprocessive class V myosin drives cargo processively when a kinesin- related protein is a passenger. Curr Biol. 2009;19:2121–2125. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JD, Brady ST, Richards BW, Stenolen D, Resau JH, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Direct interaction of microtubule- and actin-based transport motors. Nature. 1999;397:267–270. doi: 10.1038/16722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckaba TM, Lipkin T, Pon LA. Roles of type II myosin and a tropomyosin isoform in retrograde actin flow in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:957–969. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura H, Tanaka K, Hihara T, Umikawa M, Kamei T, Takahashi K, Sasaki T, Takai Y. Bni1p and Bnr1p: downstream targets of the Rho family small G-proteins which interact with profilin and regulate actin cytoskeleton in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1997;16:2745–2755. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaulin F, Xue X, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Kreitzer G. Polarization-dependent selective transport to the apical membrane by KIF5B in MDCK cells. Dev Cell. 2007;13:511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser DA, Vinson VK, Murphy DB, Pollard TD. Profilin is predominantly associated with monomeric actin in Acanthamoeba. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 21):3779–3790. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.21.3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamasaki T, Arai R, Osumi M, Mabuchi I. Directionality of F-actin cables changes during the fission yeast cell cycle. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:916–917. doi: 10.1038/ncb1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpova TS, McNally JG, Moltz SL, Cooper JA. Assembly and function of the actin cytoskeleton of yeast: relationships between cables and patches. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1501–1517. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikyo M, Tanaka K, Kamei T, Ozaki K, Fujiwara T, Inoue E, Takita Y, Ohya Y, Takai Y. An FH domain-containing Bnr1p is a multifunctional protein interacting with a variety of cytoskeletal proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Oncogene. 1999;18:7046–7054. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Harris ES, Mahaffy R, Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Control of the assembly of ATP- and ADP-actin by formins and profilin. Cell. 2006;124:423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Kuhn JR, Tichy AL, Pollard TD. The fission yeast cytokinesis formin Cdc12p is a barbed end actin filament capping protein gated by profilin. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:875–887. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Pollard TD. Insertional assembly of actin filament barbed ends in association with formins produces piconewton forces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004a;101:14725–14730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405902101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Pollard TD. Progressing actin: Formin as a processive elongation machine. Nat Cell Biol. 2004b;6:1158–1159. doi: 10.1038/ncb1204-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CJ, Malmberg RL, Muszynski MG, Dawe RK. Maximum likelihood methods reveal conservation of function among closely related kinesin families. J Mol Evol. 2002;54:42–53. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Higgs HN. The mouse Formin mDia1 is a potent actin nucleation factor regulated by autoinhibition. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1335–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00540-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie SH, Brown SS. Suppression of a myosin defect by a kinesin-related gene. Nature. 1992;356:358–361. doi: 10.1038/356358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie SH, Brown SS. Immunofluorescence localization of the unconventional myosin, Myo2p, and the putative kinesin-related protein, Smy1p, to the same regions of polarized growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:825–842. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie SH, Brown SS. Smy1p, a kinesin-related protein that does not require microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:873–883. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley JB, Goode BL. Differential activities and regulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae formin proteins Bni1 and Bnr1 by Bud6. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28023–28033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley JB, Maiti S, Goode BL. Formin proteins: purification and measurement of effects on actin assembly. Methods Enzymol. 2006;406:215–234. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)06016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley JB, Sagot I, Manning AL, Xu Y, Eck MJ, Pellman D, Goode BL. A conserved mechanism for Bni1- and mDia1-induced actin assembly and dual regulation of Bni1 by Bud6 and profilin. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:896–907. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Ravi H, Smith EM, Goode BL. Aip1 and cofilin promote rapid turnover of yeast actin patches and cables: a coordinated mechanism for severing and capping filaments. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2855–2868. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard TD, Weeds AG. The rate constant for ATP hydrolysis by polymerized actin. FEBS Lett. 1984;170:94–98. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)81376-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pring M, Evangelista M, Boone C, Yang C, Zigmond SH. Mechanism of formin-induced nucleation of actin filaments. Biochemistry. 2003;42:486–496. doi: 10.1021/bi026520j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne D, Evangelista M, Yang C, Bi E, Zigmond S, Bretscher A, Boone C. Role of formins in actin assembly: nucleation and barbed-end association. Science. 2002;297:612–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1072309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne D, Gao L, Bi E, Bretscher A. Stable and dynamic axes of polarity use distinct formin isoforms in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4971–4989. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne DW, Schott DH, Bretscher A. Tropomyosin-containing actin cables direct the Myo2p-dependent polarized delivery of secretory vesicles in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1931–1945. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero S, Le Clainche C, Didry D, Egile C, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. Formin is a processive motor that requires profilin to accelerate actin assembly and associated ATP hydrolysis. Cell. 2004;119:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose R, Weyand M, Lammers M, Ishizaki T, Ahmadian MR, Wittinghofer A. Structural and mechanistic insights into the interaction between Rho and mammalian Dia. Nature. 2005;435:513–518. doi: 10.1038/nature03604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagot I, Klee SK, Pellman D. Yeast formins regulate cell polarity by controlling the assembly of actin cables. Nat Cell Biol. 2002a;4:42–50. doi: 10.1038/ncb719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagot I, Rodal AA, Moseley J, Goode BL, Pellman D. An actin nucleation mechanism mediated by Bni1 and profilin. Nat Cell Biol. 2002b;4:626–631. doi: 10.1038/ncb834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MR, Maritzen T, Kukhtina V, Higman VA, Doglio L, Barak NN, Strauss H, Oschkinat H, Dotti CG, Haucke V. Regulation of endosomal membrane traffic by a Gadkin/AP-1/kinesin KIF5 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15344–15349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904268106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott D, Ho J, Pruyne D, Bretscher A. The COOH-terminal domain of Myo2p, a yeast myosin V, has a direct role in secretory vesicle targeting. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:791–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.4.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott DH, Collins RN, Bretscher A. Secretory vesicle transport velocity in living cells depends on the myosin-V lever arm length. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:35–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth A, Otomo C, Rosen MK. Autoinhibition regulates cellular localization and actin assembly activity of the diaphanous-related formins FRLalpha and mDia1. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:701–713. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich JA, Watt S. The regulation of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction. I. Biochemical studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin and the proteolytic fragments of myosin. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:4866–4871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Kanai Y, Okada Y, Nonaka S, Takeda S, Harada A, Hirokawa N. Targeted disruption of mouse conventional kinesin heavy chain, kif5B, results in abnormal perinuclear clustering of mitochondria. Cell. 1998;93:1147–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallen EA, Caviston J, Bi E. Roles of Hof1p, Bni1p, Bnr1p, and myo1p in cytokinesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:593–611. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavylonis D, Kovar DR, O'Shaughnessy B, Pollard TD. Model of formin-associated actin filament elongation. Mol Cell. 2006;21:455–466. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson VK, De La Cruz EM, Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Interactions of Acanthamoeba profilin with actin and nucleotides bound to actin. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10871–10880. doi: 10.1021/bi980093l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Kato T, Fujita A, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S. Cooperation between mDia1 and ROCK in Rho-induced actin reorganization. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:136–143. doi: 10.1038/11056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HC, Pon LA. Actin cable dynamics in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:751–756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022462899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonetani A, Lustig RJ, Moseley JB, Takeda T, Goode BL, Chang F. Regulation and targeting of the fission yeast formin cdc12p in cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2208–2219. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JH, Crevenna AH, Bettenbuhl M, Freisinger T, Wedlich-Soldner R. Cortical actin dynamics driven by formins and myosin V. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1533–1541. doi: 10.1242/jcs.079038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XL, Liang L, Ding YQ. Overexpression of FMNL2 is closely related to metastasis of colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1041–1047. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.