Abstract

Mitochondrial superoxide flashes (mSOFs) are stochastic events of quantal mitochondrial superoxide generation. Here, we used flexor digitorum brevis muscle fibers from transgenic mice with muscle-specific expression of a novel mitochondrial-targeted superoxide biosensor (mt-cpYFP) to characterize mSOF activity in skeletal muscle at rest, following intense activity, and under pathological conditions. Results demonstrate that mSOF activity in muscle depended on electron transport chain and adenine nucleotide translocase functionality, but it was independent of cyclophilin-D-mediated mitochondrial permeability transition pore activity. The diverse spatial dimensions of individual mSOF events were found to reflect a complex underlying morphology of the mitochondrial network, as examined by electron microscopy. Muscle activity regulated mSOF activity in a biphasic manner. Specifically, mSOF frequency was significantly increased following brief tetanic stimulation (18.1±1.6 to 22.3±2.0 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s before and after 5 tetani) and markedly decreased (to 7.7±1.6 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s) following prolonged tetanic stimulation (40 tetani). A significant temperature-dependent increase in mSOF frequency (11.9±0.8 and 19.8±2.6 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s at 23°C and 37°C) was observed in fibers from RYR1Y522S/WT mice, a mouse model of malignant hyperthermia and heat-induced hypermetabolism. Together, these results demonstrate that mSOF activity is a highly sensitive biomarker of mitochondrial respiration and the cellular metabolic state of muscle during physiological activity and pathological oxidative stress.—Wei, L., Salahura, G., Boncompagni, S., Kasischke, K. A., Protasi, F., Sheu, S.-S., Dirksen, R. T. Mitochondrial superoxide flashes: metabolic biomarkers of skeletal muscle activity and disease.

Keywords: excitation-contraction coupling, reactive oxygen species, electron transport chain, permeability transition pore, adenine nucleotide translocase

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a class of oxygen-based reactive molecules generated as a byproduct of many biological processes. Whereas ROS are traditionally viewed as primarily destructive agents produced during metabolic activity, it has more recently become clear that low levels of ROS production play important supportive and regulatory roles in many cellular events. In skeletal muscle, moderate levels of ROS play a critical role in regulating redox-sensitive gene expression, affecting cell signaling pathways and maintaining optimal contractile function (1–4). However, prolonged and excessive ROS production leads to cell injury and death. Several highly reactive free radicals are produced in skeletal muscle at rest and during activity, with superoxide (O2·−) and nitric oxide (NO·) being the predominant forms (5). Superoxide is produced by several cellular sources, including NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, nitric oxide synthase, and lipooxygenases, and in mitochondria as a byproduct of oxygen consumption due to electron slippage during electron transport chain (ETC) activity (6, 7).

Increased ROS production during prolonged strenuous exercise and muscle fatigue is well established (8, 9). Increased oxidative stress also contributes to the decline in muscle function in aging, mechanical unloading, and several inherited skeletal muscle disorders, including Duchenne muscular dystrophy, myotonic dystrophy, malignant hyperthermia (MH), and central core disease (CCD) (7). However, the relative contribution of the different potential sources of ROS production and the role of specific ROS molecules remain largely unknown. A type 1 ryanodine receptor (RYR1) knock-in mouse model of MH (RYR1Y522S/WT mice) exhibits both heat/anesthetic-induced sudden death (an MH phenotype; ref. 10) and a mitochondrial myopathy that leads to formation of cores with age (a CCD phenotype; ref. 11). Both the MH susceptibility and cores observed in these mice result at least in part from increased production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in skeletal muscle (12). However, the source of the temperature-dependent increase in oxidative stress in skeletal muscle of RYR1Y522S/WT mice is unknown.

Using a novel mitochondrial-targeted biosensor (mt-cpYFP), we previously discovered stochastic quantal events of superoxide production within the mitochondrial matrix, termed mitochondrial superoxide flashes (mSOFs). mSOF activity depends on ETC functionality and is observed across a wide variety of quiescent cells, including neurons, neuroendocrine cells, cardiac myocytes, and skeletal myotubes (13). Similar events were also recently observed using a related probe (mitochondrial-targeted ratiometric pericam) transiently expressed in quiescent adult skeletal muscle fibers (14). The conclusion that individual flash events are due to selective superoxide reactivity of the probe is based on a combination of both in vitro and intact cell experiments. First, purified cpYFP fluorescence is increased by superoxide produced by xanthine and xanthine oxidase and completely reversed by the addition of Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase (13). Second, purified cpYFP fluorescence was not altered by other reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (including H2O2, hydroxyl radical, peroxynitrate, and nitric oxide), Ca2+, ATP, ADP, NADH NAD, or redox potential (13). Third, in intact cells, flash frequency is inhibited by a superoxide dismutase mimetic (MnTMPyP) and a superoxide scavenger (tiron) (13, 14). Most important, mt-cpYFP events occur coincident with an increase in mitosox fluorescence, a widely used irreversible mitochondria-targeted superoxide-sensitive probe (14). Because mt-cpYFP detects superoxide, but not hydrogen peroxide (13), and superoxide in mitochondria is rapidly dismutated to hydrogen peroxide, then the fact that mSOF flash activity persists over several seconds is consistent with a robust burst of superoxide production within the mitochondrial matrix during this time frame.

In cardiac myocytes, mSOF activity was increased by the addition of atractyloside and reduced by both the addition of cyclosporine-A (CsA) and knockdown of cyclophilin D (CypD) (13), an essential component of Ca2+ and ROS-sensitive mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) function (15–18). On the other hand, atractyloside and CsA had no effect on mSOF frequency in adult skeletal muscle fibers (14). Thus, the relative importance of mPTP functionality in the fundamental mechanism of mSOF production is currently unclear.

While prior studies characterized mSOF properties in resting cardiac and skeletal muscle cells, little is known regarding the mechanisms that regulate and determine the spatial dynamics of mSOF activity, as well as the association of mSOF activity with normal changes in cell bioenergetics and metabolism and its potential effect on muscle disease. We hypothesized that mSOF production is tightly coupled to activity-dependent changes in muscle metabolism and that uncontrolled mSOF activity contributes to the increased temperature-dependent oxidative stress of skeletal muscle from RYR1Y522S/WT MH mice. Thus, we characterized the genesis of mSOF events from the underlying mitochondrial network and determined the ETC, adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT), and mPTP dependence of basal mSOF activity in mouse flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) fibers. We also quantified the activity dependence of mSOF production in muscle fibers during brief and prolonged repetitive tetanic stimulation, as well as the temperature dependence of mSOF production in FDB fibers from RYR1Y522S/WT MH mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of muscle-specific mt-cpYFP transgenic mice

Mt-cpYFP was constructed from mitochondrial targeted ratiometric pericam (rpericamMT; ref. 19) by removing nucleotide sequences encoding calmodulin (nt 886-1323) and its targeting sequence M13 (nt 49–126), as described previously (13). The final PCR product was digested with HindIII/XbaI and cloned into a skeletal muscle specific mt-cpYFP expression transgene vector in pcDNA3.1(+) containing a human troponin I enhancer (hTnI USE), human skeletal muscle actin (HSA) promoter, and a BGH polyadenylation signal (pcDNA3.1(+)-hTnI-HSA-BGHpA, a gift from Dr. Jeffery D. Molkentin, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA; Supplemental Fig. S1A). Mt-cpYFP (EcoRV/MluI) plus a C-terminal 3X HA-tag (MluI/NotI) was inserted between the EcoRV and NotI cloning sites after the HSA promoter via a 3-fragment ligation. The expression vector was linearized and injected into pronuclei of fertilized mouse oocytes by the University of Rochester Medical Center transgenic core facility. Mice were housed at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, and all animal protocols were approved by the University of Rochester Committee on Animal Resources. Genotyping was performed by PCR using the following primers: forward, 5′-TTCAAGGACGACGGCAACTACAAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTGCATAGTCCGGGACGTCATAGG-3′.

In vivo electroporation of mt-cpYFP cDNA into hindlimb footpads of anesthetized mice

In some experiments, mt-cpYFP was transiently expressed in adult FDB muscles following in vivo electroporation of hindlimb footpads of anesthetized mice with mt-cpYFP cDNA, using an approach described previously (20). Briefly, 3-to 4-mo wild-type (WT), RYR1Y522S/WT, and CypD−/− mice (all C57BL6 strain) were first anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine, 10 mg/kg xylazine, and 3 mg/kg acepromazine. Hindlimb footpads of anesthetized mice were then injected subcutaneously with bovine hyaluronidase (7 μl/foot, 2 μg/μl). After 1 h, hindlimb footpads were subcutaneously injected with 30 μg of mt-cpYFP cDNA (total volume 10 μl in 71 mM NaCl) using a 30-gauge needle. The footpad was then electroporated using settings of 100 V/cm, 20-ms duration, and 20 pulses delivered at 1 Hz using subcutaneous gold-plated electrodes placed perpendicularly to the long axis of the muscle, close to the proximal and distal tendons. Individual FDB fibers were isolated by enzymatic dissociation (see below) 1 wk after electroporation.

FDB muscle fiber isolation

Single muscle fibers were acutely dissociated by enzymatic digestion (1 mg/ml collagenase A, 45 min at 37°C in regular rodent Ringer solution) from FDB muscles of 2- to 4-mo-old mt-cpYFP transgenic mice and mt-cpYFP electroporated nontransgenic mice (control C57BL6, RYR1Y522S/WT, and CypD−/−). Single fibers were plated on glass-bottom dishes, allowed to settle for >30 min before being transferred to FDB culture medium (1:1 DMEM/F12, 2% FBS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin), and kept in an incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2 until needed. All fibers were used within 20 h of isolation. For confocal experiments, FDB fibers were transferred to Ringer solution containing (in mM): 146 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 MgCl, 2 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4) with or without either 10 mM glucose or mitochondrial substrates (OXPHOS: Ringer solution supplemented with 1 mM Na pyruvate, 5 mM galactose, and 4 mM glutamine). In some experiments, 10 nM tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) was also included to enable simultaneous monitoring of changes in mitochondrial membrane potential during flash activity.

Electron microscopy (EM)

After sacrifice, skin was quickly removed from the feet, and FDB muscles were fixed in situ at room temperature with fixative solution (3.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M NaCaCo buffer, pH 7.2). Small portions of muscle were postfixed, embedded, en-block stained, and sectioned for EM, as described previously (11). All sections were examined with an FP 505 Morgagni Series 268D electron microscope (Philips, Hamburg, Germany) at 60 kV equipped with a Megaview III digital camera and Soft Imaging System (Olympus, Munster, Germany).

Confocal microscopy

Mt-cpYFP and TMRE were excited using 488 nm (×8–16 attenuation) and 543 nm (×64 attenuation) lasers and detected at 515/30 and 605/75 nm emission, respectively. Images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse C1 Plus confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA) using either SuperFluor ×40 (1.3 NA) or ×60 (1.4 NA) oil-immersion objectives. Time-lapse x,y image acquisition was obtained using either 150 frames, 0.7 s/frame and 256 × 256 resolution, or 100 frames, 1.24 s/frame and 512 × 512 resolution. mSOF activity was also monitored by 2-photon excitation microscopy using a Fluoview1000 multiphoton laser-scanning microscope (Olympus Instruments, Center Valley, PA, USA) equipped with a XLPLN ×25 1.05 NA water-immersion objective. For these experiments (see Fig. 1A, B and Supplemental Movies), mt-cpYFP was excited using a MaiTai HP Deep Sea femtosecond laser (Newport Corp., Irvine, CA, USA) at 900 nm and detected using a 520- to 550-nm bandpass filter (535/50ET; Chroma, Bellows Falls, VT, USA). Time-lapse images were acquired at 512 × 512 resolution, 100 frames, 1.1 s/frame. All image acquisition parameters were kept consistent within a given set of experiments.

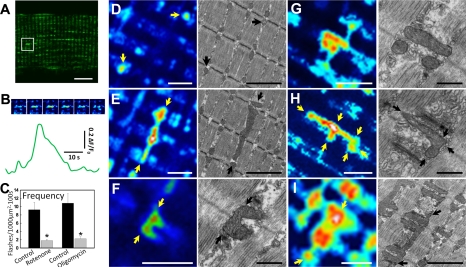

Figure 1.

Properties and spatial morphologies of mSOF activity in FDB fibers from mt-cpYFP transgenic mice. A) Representative 2-photon image of mt-cpYFP fluorescence of an FDB fiber obtained from a muscle specific mt-cpYFP transgenic mouse. Boxed area indicates a region of a rod-shaped flash that was maximal during acquisition of the displayed x,y image. B) Time course of the rod-shaped flash even in the boxed area shown in A. Top panels: series of pseudocolor time-lapse images within the boxed region shown in A (each image separated by 1.1 s). Bottom panel: time course of mt-cpYFP fluorescence within the boxed region shown in A. C) Average ± se mSOF frequency in the absence (solid bars) and presence (shaded bars) of ETC blockers rotenone (5 μM, n=10–12 fibers from 2 mice) and oligomycin (5 μM, n=10 fibers from 2 mice). *P < 0.05. D–I) Representative sd images showing the different types of mSOF morphologies observed in FDB fibers from mt-cpYFP transgenic mice (left panels) and corresponding mitochondrial disposition as observed in EM images of FDB fibers from different experiments (right panels). D) Punctate (arrows). E) Rod-shaped. F) U-shaped. G) String-like along one side of the Z line. H) String-like across the Z line. I) Patches. Arrows indicate mitochondria stretching along the A band to connect different I bands longitudinally (E, I), adjacent sarcomeres transversally (H, I), or across the Z line to connect different mitochondria within the same I band, but located on opposite sides of the Z line (F, H). Fluorescent images: scale bars = 10 μm (A); 2 μm (D–I). EM images: scale bars = 2 μm (D, E, I); 0.5 μm (F–H). Fluorescence and EM images in panels D–I were obtained from different muscle fibers. Since EM enables higher-resolution images compared to confocal microscopy, the EM images are shown at higher magnification in order to provide increased resolutions of mitochondrial positioning and ultrastructure.

Repetitive high-frequency tetanic stimulation

FDB fibers from mt-cpYFP transgenic mice were isolated as described above and bathed in Ringer solution supplemented with 30 μM N-benzyl-p-toluene sulfonamide (BTS), a skeletal muscle myosin inhibitor, to inhibit movement during electrical stimulation. Fibers were electrically stimulated with a series of 2, 5, or 40 successive tetani (500 ms duration, 100 Hz, 0.2 duty cycle) using an extracellular stimulation electrode filled with 200 mM NaCl placed adjacent to the cell of interest. mSOF activity was monitored using consecutive x,y time series confocal images (100–150 images) immediately before electrical stimulation and then 30 s, 3 min, and 6 min after termination of the final tetanus.

Event detection and analysis

Automated detection and analysis of individual mSOF events during time-lapse x,y imaging was accomplished using a newly developed, MATLAB-based program called Flash Collector (University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA). The program identifies and quantifies flash frequency, amplitude, full duration at half maximum (FDHM), time constant of decay (τd), and spatial area during the x,y acquisition time series (Supplemental Fig. S1C). For each x,y time series, stacks of 100–150 sequential images were used to calculate the sd per pixel in order to generate a sd image for the entire time series. Pixels with an sd > 35–45% of the maximum sd obtained during the time series were used to select regions of interest for further image processing and analysis. Regions with areas smaller than 3 (for 256×256 pixel images) or 5 pixels (for 512×512 pixel images) were discarded. Flash event detection was further refined using several criteria for each detected region, as follows: a threshold of M + (2.8–3.5) · sd (Supplemental Fig. S1C, inset, green line), where M and sd are the mean and sd of the mt-cpYFP fluorescence intensity of the selected area; the flash decay phase being well described by a single exponential with a decay fitting error <10; and a minimal ΔF/F0 amplitude > 0.15 (256×256 pixel images) or 0.2 (512×512 pixel images), where F0 is the average baseline fluorescence intensity of 5 frames preceding the start of the event. Flash frequency was quantified as the number of events/1000 μm2 · 100 s. FDHM, time to peak, and the exponential time of decay τd were quantified in seconds. Flash area was calculated in square micrometers. Flash Collector provides a similar analysis for all automatically detected events as that shown for the representative in the inset of Supplemental Fig. S1C.

Statistical analyses

Output data from Flash Collector were subsequently tabulated, averaged, and evaluated for statistical significance using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and SigmaPlot (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) software suites. Student's t tests for single comparison and 1-way ANOVA analysis followed by post hoc test for multiple comparisons were used, with values of P < 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

mSOF activity is coupled to mitochondrial respiration in fibers from muscle-specific mt-cpYFP transgenic mice

In order to examine mSOF activity in vivo, we generated skeletal muscle-specific mt-cpYFP transgenic mice (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Confocal images of FDB fibers from transgenic mice labeled with TMRE (a cell-permeant dye readily sequestered into mitochondria) revealed clear colocalization of mt-cpYFP (green) and TMRE (red) fluorescence in double transverse rows of fluorescence (Supplemental Fig. S1B), with a periodicity consistent with the known location of mitochondria adjacent to the calcium release units (CRUs) on either side of the Z line (21). Using 2-photon laser scanning and confocal microscopy, robust basal mSOF activity is observed in quiescent FDB muscle fibers from 3- to 4-mo-old mt-cpYFP transgenic mice (Supplemental Movie S1). A representative superoxide flash event obtained using 2-photon excitation microscopy is shown in Fig. 1A, B. The mt-cpYFP signal increases over several seconds and then decays back to baseline over the subsequent 10–20 s. mSOF activity was quantified from time-lapse x,y confocal imaging of mt-cpYFP fluorescence and analyzed using Flash Collector, a MATLAB-based automated event detection and analysis software program (Supplemental Fig. S1C, D, see Materials and Methods for details). Average mSOF frequency (Supplemental Fig. S1E), magnitude (Supplemental Fig. S1F), duration (Supplemental Fig. S1G), and area (Supplemental Fig. S1H) were similar for FDB fibers obtained from mt-cpYFP transgenic mice and control mice electroporated with mt-cpYFP cDNA. Thus, similar mSOF properties were observed following both transient and constitutive mt-cpYFP expression.

Consistent with prior studies (13, 14), mSOF frequency was markedly inhibited by ETC inhibitors, including rotenone (complex I inhibitor; 9.3±1.8 and 1.8±0.3 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s, n=10–12 fibers in the absence and presence of 5 μM rotenone, respectively) and oligomycin (complex V inhibitor; 10.8±2.3 and 2.2±0.5 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s, n=8 fibers in the absence and presence of 5 μM oligomycin, respectively) (Fig. 1C). In addition, mSOF frequency was unaltered (Supplemental Fig. S2A), while the amplitude (Supplemental Fig. S2B) and duration (Supplemental Fig. S2C) were increased, in the presence of mitochondrial substrates (1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4 mM glutamine, and 5 mM galactose or 10 mM glucose). Finally, mSOF frequency and amplitude were reduced by inhibition of ANT activity with either bongkrekic acid (BA; 17.9±0.4 and 9.9±1.5 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s, n=18–21 fibers in the absence and presence of 100 μM BA, respectively) or carboxyatractyloside (CATR, a cell-permeable form of atractyloside; 12.9±1.0 and 4.3±0.8 flashes/1000 μm2·100s, n=25–30 fibers in the absence and presence of 1 μM CATR, respectively) (Supplemental Fig. S2D–I).

mSOF spatial dimensions closely match mitochondrial disposition observed with EM

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that localize to strategic cellular areas in order to maximize their functional roles in bioenergetics, Ca2+ signaling, and ROS generation and detoxification (22–24). In type II skeletal muscle fibers, mitochondria are primarily located within the I band, tethered to the Ca2+ release unit (CRU), which limits their movement and dynamics (21). However, it remains unknown whether mitochondrial disposition is sufficient to account for the heterogeneous spatial morphologies of mSOF activity observed in skeletal muscle (14). FDB fibers exhibited a broad spectrum of superoxide flash dimensions. Representative mSOF spatial patterns observed in our studies are shown in Fig. 1D–I (left panels). Typically observed mSOF morphologies include punctate (Fig. 1D), rod-shaped (Fig. 1E), U-shaped (Fig. 1F), string-like either along (Fig. 1G) or across (Fig. 1H) the Z line, and large patches (Fig. 1I). These different mSOF morphologies correspond remarkably well with that of mitochondria observed in EM (Fig. 1D–I, right panels). Thus, the different mSOF spatial morphologies reflect a 2-dimensional projection of activity originating from an extremely complex underlying mitochondrial network, as documented in the EM images. In fact, mitochondria form a very extended and complex double-network at the I band, one on each side of the Z line, where elongated mitochondria can stretch in several orientations across several micrometers (Fig. 2A, B). This complex network results in a continuity of mitochondria that can deceptively appear to be separated in longitudinal sections (Fig. 1D, E). It is important also to note that continuity between different I-band transverse networks, even in a single longitudinal plane (see cross sections in Fig. 2A, B) is achieved by some mitochondria that either run along the A band to connect different I bands (Fig. 1E, I) or cross the Z line to connect networks located in the same I band, but on opposite sides of the Z line (Fig. 1F, H). Confocal images of mSOF activity projected in 2 dimensions across this complex mitochondrial network could explain the occurrence of multiple concurrent, yet apparently interspersed or disconnected, events across several sarcomeres (Fig. 2C).

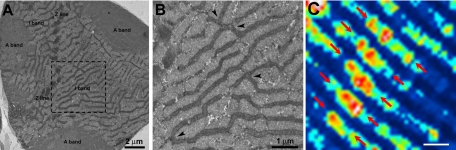

Figure 2.

EM cross-section showing complex mitochondrial reticulum within the I band that can account for large mSOF patch activity observed with confocal microscopy. A) Representative cross-section of a single FDB fiber: mitochondria are almost exclusively seen within the I band, on both sides of the Z line, where they form an extensive network. B) Higher magnification of the area marked with a dashed box in A. Arrowheads show long mitochondria running between myofibrils and being connected to other branches. C) Representative sd map generated from time-lapse images (0.7 s/frame, 150 frame total) showing large mSOF patch activity that stretches along the I band, spanning multiple sarcomeres. Red arrows indicate spatial spread of the observed patch flash activity. Such a large area of activity could reflect an extensively interconnected mitochondrial network like that shown in the EM images (A, B). Scale bars = 2 μm (A, C); 1 μm (B).

mSOF production in skeletal muscle is independent of CypD-mediated mPTP activity

Given the current uncertainty regarding the requisite role of mPTP activity in mSOF production (13, 14), we determined the effect of pharmacological and molecular inhibition of mPTP function on mSOF activity in FDB fibers. The addition of 1–5 μM CsA did not significantly alter flash frequency (8.3±1.0 and 11.4±1.3 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s fibers in the absence and presence of CsA, respectively) or amplitude (ΔF/F0 was 0.45±0.03 and 0.50±0.03 in the absence and presence of CsA, respectively) in mouse FDB fibers (Fig. 3E and ref. 14). To more rigorously evaluate the role of mPTP activity in mSOF production in skeletal muscle, we quantified mSOF activity in FDB fibers from control and CypD-knockout (CypD−/−) mice, in which mt-cpYFP was expressed by electroporation. mSOF activity in electroporated fibers was not different from that recorded in transgenic mt-cpFYP fibers (Supplemental Fig. S1E–H). Figure 3A–D shows representative mSOF events that increase over several seconds and decay to baseline with a time course over the subsequent 10–20 s. Representative mSOF events in fibers from control (Fig. 3A, B) and CypD−/− mice (Fig. 3C, D) exhibit a similar magnitude and time course and occurred concomitantly with depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential, as indicated by a transient reduction in TMRE fluorescence (Fig. 3B, D, red traces). Average mSOF amplitude (Fig. 3E; WT=0.53±0.02 and CypD−/−=0.58±0.03), frequency (Fig. 3E; WT=9.9±1.4 and CypD−/−=9.0±0.8 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s), duration (Fig. 3F; FDHM, WT=2.9±0.2 s and CypD−/−=2.7±0.2 s), and ETC dependence (Fig. 3G) were not significantly different for FDB fibers from control (n=22 fibers) and CypD−/− (n=23 fibers) mice.

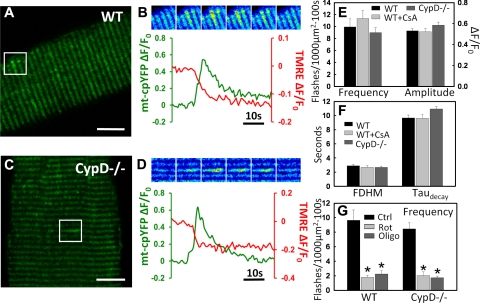

Figure 3.

mSOF activity does not require CypD-dependent mPTP functionality. A) Representative mt-cpYFP confocal image of an FDB fiber obtained from a WT mouse electroporated with mt-cpYFP cDNA; boxed region indicates an area containing mSOF activity. B) Time course of mt-cpYFP fluorescence within the boxed region shown in A. Top panels: series of pseudocolor time-lapse images. Bottom panel: time course of simultaneously recorded mt-cpYFP (green) and TMRE (red) fluorescence for the individual flash event. C, D) Same as A, B except for an FDB fiber obtained from a CypD−/− mouse electroporated with mt-cpYFP cDNA. E, F) Average ± se basal mSOF frequency (E, left), amplitude (E, right), FDHM (F, left) and decay rate (F, right) in FDB fibers obtained from WT and CypD−/− mice (n=22–23 fibers from 2 WT and 2 CypD−/− mice) and WT FDB fibers in the presence of 1 μM CsA (n=14–17 fibers from 2 mice). G) Rotenone (5 μM) and oligomycin (5 μM) similarly inhibit mSOF frequency in FDB fibers from WT (left) and CypD−/− (right) mice (n=8–12 fibers from 2 WT and 2 CypD−/− mice). Scale bars = 10 μm. *P < 0.05.

Biphasic activity-dependent regulation of mSOF production in FDB fibers

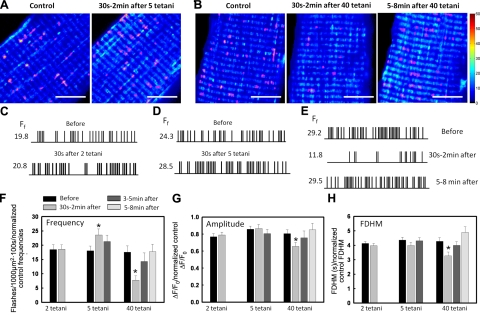

Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake stimulates aerobic respiration by enhancing the activity of several dehydrogenases of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the ATP synthetic activity of the F1F0 ATPase (25). Because mSOF activity depends on ETC activity, and mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake increases during repetitive tetanic stimulation (26), we determined the effect of brief (2 tetani), moderate (5 tetani), and prolonged (40 tetani) repetitive tetanic stimulation (500 ms, 100 Hz, 0.2 duty cycle) on the frequency and properties of mSOF activity. Time-lapse images were taken before stimulation, immediately after stimulation, and after 3–8 min of recovery (Fig. 4A, B). The results revealed an unexpected bimodal response of mSOF activity to different stimulation loads. Whereas no significant changes were observed after only two tetani (Fig. 4C; F–H, left), a significant increase (27±8.9%) in mSOF frequency (18.1±1.6 and 22.3±2.0 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s, n=24 fibers before and after stimulation, respectively) was observed following 5 successive tetani (Fig. 4A; D; F, middle). The increase in mSOF frequency following 5 tetani subsided following 5 min of recovery (Fig. 4F, middle) and was not accompanied by significant changes in mSOF amplitude (Fig. 4G, middle) or duration (Fig. 4H, middle). Remarkably, prolonged repetitive tetanic stimulation had the opposite effect on mSOF activity: mSOF frequency was dramatically suppressed (from 17.6±2.2 to 7.7±1.6 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s, n=9 fibers) following 40 tetani (Fig. 4B; E; F, right). This reduction in mSOF activity was accompanied by a significant, though less dramatic, reduction in flash amplitude (Fig. 4G, right; ΔF/F0 was reduced from 0.80±0.05 to 0.65±0.03) and duration (Fig. 4H, right; FDHM was reduced from 4.3±0.3 s to 3.1±0.3 s). The reductions in flash frequency, amplitude, and duration following 40 tetani all recovered to normal levels 3–8 min following termination of the final tetanus (Fig. 4F–H, right).

Figure 4.

Biphasic regulation of mSOF activity by repetitive high-frequency tetanic stimulation. A) sd maps (100 images, 1.24 s/frame) for a representative FDB fiber before and immediately after 5 tetanic stimuli (500 ms, 100 Hz, 0.2 duty cycle). B) sd maps (100 images 1.24 s/frame) for a representative FDB fiber before, 30 s after, and 5 min after 40 tetanic stimuli (500 ms, 100 Hz, 0.2 duty cycle). Magenta borders indicate identified events. Scale bars = 10 μm. C–E) Schematic registry of individual mSOF events in representative control FDB fibers from mt-cpYFP transgenic mice before and 30 s after 2 tetani (C), before and 30 s after 5 tetani (D), and before and 30 s to 2 min after and 5–8 min after 40 tetani (E). Calculated flash frequencies Ff are indicated at left of each registry. F–H) Average ± se mSOF frequency (F), amplitude (G), and FDHM (H) before and after 2, 5, and 40 tetani (n=9–24 fibers from 7 mice). Data are normalized to control frequency, amplitude, and duration from consecutive time series taken in control fibers in the absence of stimulation in order to control for time/exposure-dependent changes in flash activity. Although no significant change in flash frequency, amplitude, and FDHM was seen for any of the 4 consecutive control time series, data were normalized against the appropriate control time series value. *P < 0.05.

Temperature-dependent regulation of mSOF production in FDB fibers from control and RYR1Y522S/WT MH knock-in mice

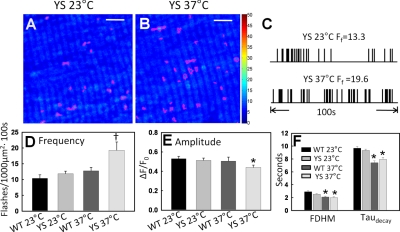

Skeletal muscle fibers from a mouse model of MH (RYR1Y522S/WT mice) exhibit marked temperature-dependent increases in ROS/RNS generation (12) that plays a central role in MH susceptibility (10, 12) and the formation of metabolically inert cores (11). Therefore, we characterized the temperature dependence of mSOF activity in skeletal muscle fibers from control and RYR1Y522S/WT MH mice. To determine whether increased mSOF activity contributes to the enhanced temperature-dependent oxidative stress of RYR1Y522S/WT mice, mt-cpYFP was expressed in FDB muscle of WT and RYR1Y522S/WT mice via in vivo electroporation. mSOF frequency (Fig. 5D; 10.4±1.1, n=34 and 11.9±0.8 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s, n=48 in WT and YS fibers, respectively), amplitude (Fig. 5E; 0.55±0.02 and 0.51±0.02 in WT and YS fibers, respectively), and duration (Fig. 5F; 2.7±0.15 and 2.5±0.1 s in WT and YS fibers, respectively) at 23°C were not significantly different for FDB fibers from WT and RYR1Y522S/WT mice. However, mSOF frequency increased 68 ± 11% at 37°C (to 19.8±2.6 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s, n=18) in FDB fibers from RYR1Y522S/WT mice, but not in fibers from WT mice (12.8±1.1 flashes/1000 μm2·100 s, n=24) (Fig. 5A–D). In addition, flash amplitude (0.44±0.1) and FDHM (2.1±0.1 s) duration were modestly reduced at 37°C in fibers from RYR1Y522S/WT mice (Fig. 5E, F).

Figure 5.

Temperature dependence of mSOF production in FDB fibers from RYR1Y522S/WT MH mice. A, B) sd maps (150 images, 0.69 s/frame) for a representative FDB fiber obtained from a RYR1Y522S/WT mouse at 23°C (A) and 37°C (B). Magenta borders indicate identified events. Scale bars = 10 μm. C) Schematic flash registry over time for the fiber depicted in A at 23°C (upper) and 37°C (lower). Calculated flash frequency Ff for each condition is indicated above the corresponding registry trace. D–F) Average ± se mSOF frequency (D), amplitude (E), and FDHM and decay rate (F) at 23°C and 37°C for FDB fibers obtained from WT and RYR1Y522S/WT mice (n=18–48 fibers from 5 WT and 5 RYR1Y522S/WT mice). *P < 0.05 vs. appropriate control; †P < 0.05 vs. all other conditions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized the properties and regulation of mSOF activity in single adult skeletal muscle fibers under physiological (rest and following tetanic stimulation) and pathological (RYR1Y522S/WT mice) conditions. A robust basal mSOF activity with highly heterogeneous spatial morphologies is detected in quiescent fibers, consistent with the complex 3-dimensional mitochondrial network inferred from electron microscopic analysis of FDB muscle. mSOF activity depends strongly on ETC and ANT functionality, consistent with mSOF activity representing stochastic transient accelerations in mitochondrial respiration, and thus are a reliable biomarker of the cellular metabolic state. In contrast to that observed in cardiac myocytes (13), mSOF activity in skeletal muscle fibers is independent of CypD-mediated mPTP activity. In addition, we provide the first evidence that mitochondrial superoxide production undergoes biphasic and reversible regulation in response to repetitive tetanic stimulation. Finally, we also demonstrate a temperature-dependent increase in mSOF production in muscle fibers from adult RYR1Y522S/WT mice that would contribute to the increased skeletal muscle oxidative stress that underlies the increased MHS, mitochondrial damage, and development of cores observed in these mice (11, 12).

Roles of the ETC, ANT, and mPTP in mSOF generation

Results presented here agree, in part, with those reported previously for basal mSOF activity in cardiac myocytes (13) and skeletal muscle fibers (14). Specifically, spontaneous mSOFs in skeletal and cardiac muscle cells exhibit similar average amplitudes (ΔF/F∼0.5–1.0), rise time (tp∼5 s), duration (τd∼10 s), and spatial width (area∼1 μm2). In addition, mSOF activity occurs coincident with transient mitochondrial membrane depolarization and is inhibited by ETC blockers. An important difference between our results and those of prior studies is that we found that mSOF frequency and magnitude are significantly reduced by 1 μM CATR (Supplemental Fig. S4A–D). Wang et al. (13) found that atractyloside modestly increased mSOF frequency in cardiac myocytes, while Pouvreau (14) found no effect of atractyloside in mouse FDB fibers. The reasons for the differential effects of atractyloside across these studies are not entirely clear. One possible reason for why we were able to resolve an inhibition in FDB fibers is that our experiments used the more readily membrane-permeant and high-affinity carboxylated form of atractyloside, while those of Pouvreau (14) used only the noncarboxylated form. Indeed, consistent with the findings in Pouvreau (14), we also failed to observe an effect using 20 μM noncarboxylated atractyloside on mSOF frequency or amplitude (Supplemental Fig. S2H, I). The ANT is the single most abundant protein in the inner mitochondrial membrane and serves as a site of convergence for oxidative phosphorylation. Since both BA and CATR inhibit ANT activity and reduce mSOF frequency and magnitude (Supplemental Fig. S2F, G), our results are consistent with an important role for ANT-mediated ADP/ATP exchange in setting the rate of mitochondrial respiration, cellular metabolism, and thus, mSOF generation.

The importance of stochastic openings of the mPTP in mSOF generation is unclear. In cardiac myocytes, mSOF activity was reduced by both CsA and CypD knockdown (13), consistent with a requisite role for the mPTP. However, Pouvreau (14) found no effect of CsA on flash activity in skeletal muscle fibers, a result also confirmed here (Fig. 3E, F). To more rigorously test the role of CypD-dependent mPTP activity in mSOF production in adult skeletal muscle, we compared flash activity in FDB fibers from control and CypD−/− mice. Consistent with the lack of an effect of CsA treatment in FDB fibers from control mice, mSOF frequency, amplitude, and properties were unaltered in FDB fibers from CypD−/− mice (Fig. 3). Thus, unlike that reported for cardiomyocytes (13), mSOF production in skeletal muscle occurs independent of stochastic mPTP openings. Thus, although the relative role of mPTP functionality in mSOF generation appears to be tissue-dependent, a more comprehensive understanding of the reasons that underlie this difference will require further work.

Spatial heterogeneity and propagation of mSOF activity

Recordings of mSOF activity in skeletal muscle fibers brought to our attention 2 key features: individual mSOF events exhibit a variety of morphological appearances; and events can spread both transversally and longitudinally (Supplemental Movie S2) over several micrometers within and between myofibrils/sarcomeres. Both features can be explained by the complex architecture of the skeletal muscle metabolic machinery. Both confocal and electron microscopic images represent projected 2-dimensional sections of a given plane across the muscle fiber, with the z depth of confocal images being much thicker (∼500 nm) than that obtained from electron micrographs (∼60 nm). Mitochondria form a very complex network in skeletal muscle fibers that develop transversally in two main networks for each I band, one on each side of the Z line (see Fig. 2A, B). In addition, each network is connected to one another by a few longitudinal branches of mitochondria that either run along the A band to connect different I bands (Fig. 1E, I) or cross the Z line to connect networks located within the same I band, but on opposite sides of the Z line (Fig. 1F, H). For instance, mSOF activity observed within elongated linear regions (e.g., Fig. 1E) and large patches (e.g., Fig. 2C) likely reflects regenerative superoxide generation through an extended mitochondrion and/or across a network of functionally interconnected and actively respiring mitochondria. Indeed, from high-resolution 2-photon excitation time-lapse imaging, nondecaying flash activity is seen to propagate within such regions at a calculated speed of 1–3 μm/s (Supplemental Movie S2). Given the highly reactive nature of superoxide (1), this nondecaying signal propagation could not reflect diffusion of superoxide from a point source. Rather, the observed signal propagation more likely reflects regenerative spread of ETC-dependent superoxide generation along the mitochondrion. Given the limited z-axis depth of confocal x,y images, the discrete punctate events observed in this study likely reflect propagation of an mSOF event within an extended mitochondrion that transits into and out of the sampled confocal plane. This notion is supported by the extensive reticulated mitochondrial network shown in EM images of I-band cross-sections (Supplemental Fig. S2A, B). Finally, the heterogeneous mSOF morphologies observed in this study could also reflect ongoing mitochondrial fission, fusion, and movement within the limited three-dimensional space of the I band.

An mSOF propagation speed of 1–3 μm/s is >20 times slower than values calculated for the propagation speed of cytosolic Ca2+ waves (27, 28) and mitochondrial membrane depolarization (29). Thus, mSOF activity is likely initiated at a hotspot of high ETC activity within the mitochondrial inner membrane, and then the signal propagates via a regenerative process of superoxide production, similar to ROS-induced ROS release (29, 30). Consistent with this idea, it has been shown that the ETC complexes I–V form oligomeric supercomplexes (or mitochondrial respirasome) that facilitate highly efficient substrate channeling (31). Given their observed propagation and strong dependence on mitochondrial respiration, mSOF activity may reflect intramitochondrial and intermitochondrial ROS signaling and energy transfer within the cell. In this case, ROS signals may be transmitted through the “mitochondrial reticulum,” a structure formed between outer-inner membranes of interconnected or end-to-end associated mitochondria (Fig. 2; ref. 32).

mSOF dependence on muscle activity

An important unexpected finding of this work is that repetitive tetanic stimulation exerts a biphasic effect on mSOF production, with an increase in frequency observed after moderate stimulation (5 tetani) and a reduction in frequency, amplitude, and duration following intense activity (40 successive tetani). Since mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is increased during muscle excitation (26), and increases in mitochondrial Ca2+ stimulate several Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenases and the ATP synthetic capacity of the F1F0-ATPase (25, 33), the increase in flash frequency observed following 5 successive stimulation may reflect Ca2+-mediated enhancement in ETC activity. Definitive evidence for this mechanism will require demonstrating that activity-dependent changes in mSOF activity are blocked by inhibitors of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. The marked reduction in flash frequency, amplitude, and duration observed after 40 tetani was surprising, since total cellular ROS levels increase substantially during repetitive high-frequency stimulation and thus contribute to a decrease in force production associated with fatigue (6, 9, 34). The decrease in mSOF frequency is unlikely due to irreversible damage of the mt-cpYFP probe, since flash activity recovered to control levels 5–8 min after the termination of stimulation. Rather, the observed reduction in flash production following prolonged tetanic stimulation could be due to the production of metabolites and/or acid accumulation that serve a protective function by inhibiting ETC activity, and thus, further ROS production. Alternatively, ROS leak through the electron transport chain may be suppressed by an increase in ADP (stage 3 respiration) or a decrease in ATP/ADP during repetitive stimulation (35, 36). In any event, the decrease in mSOF activity that occurs after prolonged tetanic stimulation indicates that uncontrolled mSOF activity is not a major contributor to increased cellular levels of ROS that occur during muscle fatigue.

Uncontrolled mSOF activity contributes to enhanced muscle oxidative stress of MH mice

mSOF activity is not only regulated by muscle activity, but when not properly controlled, can also contribute to increased oxidative stress in disease (13). The preferential temperature-dependent enhancement in mSOF production observed in FDB fibers from RYR1Y522S/WT mice (Fig. 5) parallels a similar temperature-dependent increase in RYR1 Ca2+ leak, resting myoplasmic Ca2+, and oxidative stress in muscle fibers from these mice (10, 12). Our results are consistent with a temperature-dependent increase in RYR1 Ca2+ leak and resting Ca2+-enhancing cellular ROS levels, in part, via stimulation of basal mSOF production. Increased superoxide production by mitochondria tethered immediately adjacent to the Ca2+ release unit (21), in turn, would promote RYR1 oxidation to further potentiate Ca2+ leak in a vicious feed-forward cycle of increased RyR1 Ca2+ leak, mitochondrial ROS production, and oxidative stress (12). Ultimately, this destructive feed-forward cycle may lead to the MH susceptibility, weakness, structural muscle deterioration, mitochondrial injury, and core development observed in skeletal muscle of RYR1Y522S/WT mice (10–12, 37), consistent with a central role of altered mSOF activity in the cellular pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie MH, CCD, and possibly other oxidative stress-related disorders. While our findings indicate a remarkable correlation between increased temperature-dependent mSOF generation with the increase in muscle oxidative stress of RYR1Y522S/WT mice, future work is needed to demonstrate causation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides essential new insight into the mechanism of mSOF production in skeletal muscle and the role of these events in muscle metabolism. We provide compelling evidence for mSOF as a highly sensitive biomarker of the cellular metabolic state of skeletal muscle. While ETC-dependent mSOF activity is increased initially during intense muscle activity, it decreases significantly during prolonged repetitive stimulation, an effect that acts as a protective “safety break” on mitochondrial ROS production. In addition, uncontrolled mSOF production likely contributes to the pathogenic temperature-dependent increase in oxidative stress of RYR1Y522S/WT MH mice. Indeed, the skeletal muscle-specific mt-cpYFP transgenic mice generated here will be an extremely powerful tool for future studies designed to evaluate the role of mSOF dysfunction in other oxidative stress-related skeletal muscle disorders, including aging and muscular dystrophy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jeffery D. Molkentin (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA) for providing the CypD−/− mice and skeletal muscle-specific vector used to generate the mt-cpYFP transgenic mice used in this study. The authors also thank Linda Groom (University of Rochester Medical Center) for generating the muscle-specific mt-cpYFP construct used to make the transgenic mice used in this study. The authors thank Dr. Susan L. Hamilton (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA) for constructive comments on the manuscript and for providing access to the RYR1Y522S/WT mice used in this work. The 2-photon imaging studies were performed in the Multiphoton Core Facility of the University of Rochester Medical Center.

This research was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants AR44657 (to R.T.D.) and HL033333 (to S.S.S.), Italian Telethon ONLUS Foundation grant GGP08153 (to F.P.), and the Academia Dei Lincea Fund (to L.W.).

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Droge W. (2002) Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 82, 47–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smith M. A., Reid M. B. (2006) Redox modulation of contractile function in respiratory and limb skeletal muscle. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 151, 229–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rhee S. G. (2006) Cell signalling: H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science 312, 1882–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reid M. B., Shoji T., Moody M. R., Entman M. L. (1992) Reactive oxygen in skeletal muscle. II. Extracellular release of free radicals. J. Appl. Physiol. 73, 1805–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jackson M. J., Pye D., Palomero J. (2007) The production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 102, 1664–1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Allen D. G., Lamb G. D., Westerblad H. (2008) Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol. Rev. 88, 287–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moylan J. S., Reid M. B. (2007) Oxidative stress, chronic disease, and muscle wasting. Muscle Nerve 35, 411–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jackson M. J., Edwards R. H. T., Symons M. C. R. (1985) Electron spin resonance studies of intact mammalian skeletal muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 847, 185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Powers S. K., Jackson M. J. (2008) Exercise-induced oxidative stress: cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol. Rev. 88, 1243–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chelu M. G., Goonasekera S. A., Durham W. J., Tang W., Lueck J. D., Riehl J., Pessah I. N., Zhang P., Bhattacharjee M. B., Dirksen R. T., Hamilton S. L. (2006) Heat- and anesthesia-induced malignant hyperthermia in an RyR1 knock-in mouse. FASEB J. 20, 329–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boncompagni S., Rossi A. E., Micaroni M., Hamilton S. L., Dirksen R. T., Franzini-Armstrong C., Protasi F. (2009) Characterization and temporal development of cores in a mouse model of malignant hyperthermia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 21996–22001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Durham W. J., Aracena-Parks P., Long C., Rossi A. E., Goonasekera S. A., Boncompagni S., Galvan D. L., Gilman C. P., Baker M. R., Shirokova N., Protasi F., Dirksen R., Hamilton S. L. (2008) RyR1 S-nitrosylation underlies environmental heat stroke and sudden death in Y522S RyR1 knockin mice. Cell 133, 53–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang W., Fang H., Groom L., Cheng A., Zhang W., Liu J., Wang X., Li K., Han P., Zheng M., Yin J., Mattson M. P., Kao J. P., Lakatta E. G., Sheu S. S., Ouyang K., Chen J., Dirksen R. T., Cheng H. (2008) Superoxide flashes in single mitochondria. Cell 134, 279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pouvreau S. (2010) Superoxide flashes in mouse skeletal muscle are produced by discrete arrays of active mitochondria operating coherently. PLoS ONE 5, e13035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baines C. P., Kaiser R. A., Purcell N. H., Blair N. S., Osinska H., Hambleton M. A., Brunskill E. W., Sayen M. R., Gottlieb R. A., Dorn G. W., Robbins J., Molkentin J. D. (2005) Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature 434, 658–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakagawa T., Shimizu S., Watanabe T., Yamaguchi O., Otsu K., Yamagata H., Inohara H., Kubo T., Tsujimoto Y. (2005) Cyclophilin D-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition regulates some necrotic but not apoptotic cell death. Nature 434, 652–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Basso E., Fante L., Fowlkes J., Petronilli V., Forte M. A., Bernardi P. (2005) Properties of the permeability transition pore in mitochondria devoid of cyclophilin D. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 18558–18561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schinzel A. C., Takeuchi O., Huang Z., Fisher J. K., Zhou Z., Rubens J., Hetz C., Danial N. N., Moskowitz M. A., Korsmeyer S. J. (2005) Cyclophilin D is a component of mitochondrial permeability transition and mediates neuronal cell death after focal cerebral ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 12005–12010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nagai T., Sawano A., Park E. S., Miyawaki A. (2001) Circularly permuted green fluorescent proteins engineered to sense Ca2+. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 3197–3202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. DiFranco M., Ñeco P., Capote J., Meera P., Vergara J. L. (2006) Quantitative evaluation of mammalian skeletal muscle as a heterologous protein expression system. Protein Expr. Purif. 47, 281–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boncompagni S., Rossi A. E., Micaroni M., Beznoussenko G. V., Polishchuk R. S., Dirksen R. T., Protasi F. (2009) Mitochondria are linked to calcium stores in striated muscle by developmentally regulated tethering structures. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1058–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ernster L., Schatz G. (1981) Mitochondria: a historical review. J. Cell Biol. 91, 227s–255s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rizzuto R., Bernardi P., Pozzan T. (2000) Mitochondria as all-round players of the calcium game. J. Physiol. 529, 37–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Green D. R., Kroemer G. (2004) The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science 305, 626–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balaban R. S. (2002) Cardiac energy metabolism homeostasis: role of cytosolic calcium. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 34, 1259–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rudolf R., Mongillo M., Magalhaes P. J., Pozzan T. (2004) In vivo monitoring of Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria of mouse skeletal muscle during contraction. J. Cell Biol. 166, 527–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giovannucci D. R., Bruce J. I., Straub S. V., Arreola J., Sneyd J., Shuttleworth T. J., Yule D. I. (2002) Cytosolic Ca2+ and Ca2+-activated Cl− current dynamics: insights from two functionally distinct mouse exocrine cells. J. Physiol. 540, 469–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Won J. H., Cottrell W. J., Foster T. H., Yule D. I. (2007) Ca2+ release dynamics in parotid and pancreatic exocrine acinar cells evoked by spatially limited flash photolysis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 293, G1166–G1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aon M. A., Cortassa S., O'Rourke B. (2004) Percolation and criticality in a mitochondrial network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 4447–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou L., Aon M. A., Almas T., Cortassa S., Winslow R. L., O'Rourke B. (2010) A reaction-diffusion model of ROS-induced ROS release in a mitochondrial network. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dudkina N. V., Kouril R., Peters K., Braun H.-P., Boekema E. J. (2010) Structure and function of mitochondrial supercomplexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 664–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bakeeva L. E., Chentsov Yu S., Skulachev V. P. (1978) Mitochondrial framework (reticulum mitochondriale) in rat diaphragm muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 501, 349–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brookes P. S., Yoon Y., Robotham J. L., Anders M. W., Sheu S. S. (2004) Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 287, C817–C833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jackson M. J., Papa S., Bolaños J., Bruckdorfer R., Carlsen H., Elliott R. M., Flier J., Griffiths H. R., Heales S., Holst B., Lorusso M., Lund E., Øivind Moskaug J., Moser U., Di Paola M., Cristina Polidori M., Signorile A., Stahl W., Viña-Ribes J., Astley S. B. (2002) Antioxidants, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, gene induction and mitochondrial function. Mol. Aspects Med. 23, 209–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Di Meo S., Venditti P. (2001) Mitochondria in exercise-induced oxidative stress. Biol. Signals Recept. 10, 125–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Herrero A., Barja G. (1997) ADP-regulation of mitochondrial free radical production is different with complex I- or complex II-linked substrates: implications for the exercise paradox and brain hypermetabolism. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 29, 241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andronache Z., Hamilton S. L., Dirksen R. T., Melzer W. (2009) A retrograde signal from RyR1 alters DHP receptor inactivation and limits window Ca2+ release in muscle fibers of Y522S RyR1 knock-in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 4531–4536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.