Lipoxins and resolvins regulate primary human mϕ responses to E. coli to enhance TNF production and phagocytic killing while reducing TNF production to purified LPS.

Keywords: eicosanoid, TNF, IL-6, resolution of inflammation

Abstract

Detection and clearance of bacterial infection require balanced effector and resolution signals to avoid chronic inflammation. Detection of GNB LPS by TLR4 on mϕ induces inflammatory responses, contributing to chronic inflammation and tissue injury. LXs and Rvs are endogenous lipid mediators that enhance resolution of inflammation, and their actions on primary human mϕ responses toward GNB are largely uncharacterized. Here, we report that LXA4, LXB4, and RvD1, tested at 0.1–1 μM, inhibited LPS-induced TNF production from primary human mϕ, with ATL and 17(R)-RvD1, demonstrating potent inhibition at 0.1 μM. In addition, 17(R)-RvD1 inhibited LPS-induced primary human mϕ production of IL-7, IL-12p70, GM-CSF, IL-8, CCL2, and MIP-1α without reducing that of IL-6 or IL-10. Remarkably, when stimulated with live Escherichia coli, mϕ treated with 17(R)-RvD1 demonstrated increased TNF production and enhanced internalization and killing of the bacteria. 17(R)-RvD1-enhanced TNF, internalization, and killing were not evident for an lpxM mutant of E. coli expressing hypoacylated LPS with reduced inflammatory activity. Furthermore, 17(R)-RvD1-enhanced, E. coli-induced TNF production was evident in WT but not TLR4-deficient murine mϕ. Thus, Rvs differentially modulate primary human mϕ responses to E. coli in an LPS- and TLR4-dependent manner, such that this Rv could promote resolution of GNB/LPS-driven inflammation by reducing mϕ proinflammatory responses to isolated LPS and increasing mϕ responses important for clearance of infection.

Introduction

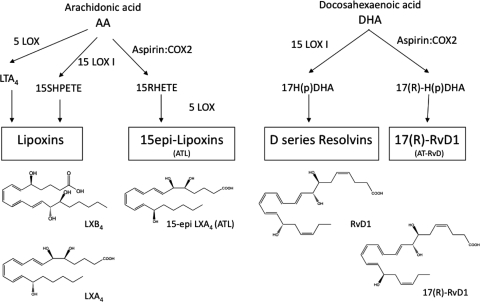

Detection and clearance of microbial infection require balanced orchestration of effector and resolution signals to avoid chronic inflammation. Detection of GNB includes recognition of bacterial LPS by TLR4 on mϕ that induces production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF [1–3]. Resolution of inflammation is an active process mediated by endogenous host factors such as eicosanoid and docosanoid lipid mediators, including proresolving LXs and Rvs (Fig. 1) [4, 5]. LXA4 and RvE1 each reduce production of proinflammatory mediators, enhance anti-inflammatory responses, promote wound healing, and are not immunosuppressive in experimental animal disease models in vivo [4, 6–10].

Figure 1. General scheme for biosynthesis of LXs, RVs, and their ATLs.

Simplified overview of LX and RV production in human tissues from AA and DHA, respectively, involving LOX and aspirin-acetylated COX-2. The structures and complete stereochemical assignments shown are established for these mediators (for review, see ref. [4]). AT-RvD, aspirin-triggered RvD.

Tissue resident mϕ are often an early point of contact of the immune system with invading pathogens at sites of tissue injury [11–13] and can enhance PMN recruitment into inflamed tissues in response to injury or infection [14]. Mϕ can phagocytose and kill bacteria [15, 16], and more virulent strains of Escherichia coli survive longer within mϕ after phagocytosis, suggesting that the efficiency of mϕ killing of internalized E. coli may play a role in determining the severity of a bacterial infection [17]. Thus, the extent and rapidity of mϕ killing of internalized bacteria affect induction and resolution of inflammation. GNB represent a substantial portion of the human commensal microbiome [18], and E. coli in particular, can cause a variety of infections [19–21]. GNB release free LPS as membrane blebs [22], and accordingly, in conditions where intestinal barrier integrity is compromised, LPS can also enter the peripheral circulation in the absence of detectable bacterial infection (i.e., despite negative blood cultures) [21, 23, 24]. GNB/endotoxemia induces TLR4-mediated TNF production that contributes to the initiation of cardiovascular shock [25, 26] and has been implicated in a wide range of inflammatory conditions [27]. Efforts to understand and modulate GNB infections and endotoxemia have been ongoing [28], and efforts to develop vaccines to treat or prevent sepsis have faced substantial challenges [29–31], necessitating further characterization of host-GNB interactions to identify approaches to modulate these responses without rendering patients immunosuppressed [32].

Detection of picogram amounts of LPS by the mϕ CD14/TLR4/MD-2 receptor complex induces production of cytokines, including TNF, which mediates cell adherence, chemotaxis, degranulation, and the respiratory burst [33, 34], and also contributes to fever and cachexia [35]. Under appropriate conditions, mϕ mediate resolution of inflammation by changing cytokine expression profiles from predominantly proinflammatory to resolving and anti-inflammatory [36–38]. Resolution of inflammation is an active process that involves time-dependent eicosanoid lipid mediator ″class switching″ from proinflammatory LTs to proresolving LXs and Rvs [4, 39], a process delayed or disrupted in chronic inflammation [40]. Quiescent human monocytes up-regulate the expression of the LXA4 receptor, ALX, as they differentiate into mϕ during inflammation [41], and LXA4 inhibits LPS-induced NF-κB activation and TNF protein production in murine mϕ [42–44]. RvD1 reduces LPS-induced TNF production in murine bone marrow-derived mϕ [7] and increases phagocytosis of apoptotic PMN and STZ by human GM-CSF-driven mϕ [45]. LXA4 and RvE1 enhance phagocytosis of apoptotic PMN, STZ, and E. coli in murine peritoneal and human HL-60- and THP-1-derived, as well as GM-CSF-driven, mϕ, and RvE1 enhances clearance of E. coli in mice in vivo [6, 7, 9, 10, 45, 46]. In addition, RvD2 enhances phagocytosis of E. coli by human PMN and increases survival and resolution of inflammation in mice challenged with E. coli [47–49]. Primary human mϕ generated in the absence of additional cytokines may reflect resident tissue mϕ more closely and might therefore be an important in vitro model for translational approaches. Recent findings showed that ATL increased nonphlogistic phagocytosis of apoptotic PMN by primary human mϕ [8], and can also enhance expression of LPS-neutralizing PBI on human mucosal epithelia [50]. Little is known regarding the effects of LXs and Rvs on responses of these cells to GNB.

Herein, we characterize for the first time the effects of specific LXs and Rvs on LPS-induced cytokine production by primary human mϕ (generated in the absence of cytokine stimuli) when exposed to purified LPS or live E. coli expressing WT or lpxM mutant LPS species [51–53] with potent and weak TLR4 agonist properties [54], respectively. We demonstrate that although the LXs and Rvs tested each reduce TNF production by primary human mϕ stimulated with purified LPS, 17(R)-RvD1 enhances LPS/TLR4-dependent TNF responses to live E. coli, which is accompanied by increased phagocytic killing by these cells. These novel observations suggest that specific Rvs can modulate primary human mϕ responses to LPS in a way that favors resolution of GNB/LPS-driven inflammation—enhancing TNF induction when presented in the context of live bacteria and promoting clearance of infection [21, 55] while blunting responses to bacteria-free LPS that may otherwise trigger excessive/chronic inflammatory responses [56].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

LX and Rv

LXA4 and ATL were purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ, USA), and LXB4, RvD1, and, 17(R)-RvD1 were from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). To ensure compound stability, LXs and Rvs were prepared in an N2-enriched atmosphere and light-free conditions, as described [57].

Blood donors

Peripheral blood was obtained after informed consent from healthy adult volunteers according to CHB Internal Review Board-approved protocols (Boston, MA, USA). Number of repeats (n) always denotes number of independent experiments. For primary human cells, no subject was studied more than once in each of the different experiments.

Mϕ isolation, culture, and stimulation

Peripheral venous blood was collected into syringes containing 5 U/ml heparin. Mononuclear cells were isolated by differential centrifugation (2200 rpm, 30 min) over Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway) and mϕ differentiated as described previously [21, 58]. Briefly, monocytes were allowed to adhere to plastic in serum-free RPMI for 2 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, nonadherent cells removed, and mϕ differentiated in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% HI FBS (Invitrogen) for 5 days. Adherent cells were scraped on Day 5 and replated at a density of 106 cells/mL in RPMI with 10% HI FBS. Plated mϕ were incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2, and then stimulated as indicated. WT and TLR4-deficient murine peritoneal exudate-derived mϕ derived from TLR4-deficient and isogenic control 129/SvJ mice, originally obtained from Dr. Shizuo Akira's laboratory (Osaka Unversity, Japan) [2], were kindly provided by Dr. Douglas Golenbock (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA) and have been described previously [59, 60].

Murine mϕ were maintained in RPMI with 5% HI FBS at 37°C, 5% CO2. Adherent cells were scraped when confluent and replated at a density of 106 cells/mL in RPMI with 5% HI FBS. Plated mϕ were incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. Stimuli used were LPS (List Laboratories, Campbell, CA, USA) at 10 ng/ml, live WT E. coli strain K12 W3110 (WT), and its isogenic lpxM mutant K12 W3110 MLK1067 strain, deficient in secondary acyl chains on lipid A (kindly provided by Dr. Christian Raetz, Duke University Medical School, Durham, NC, USA) [51–53] at a MOI of 50:1. Mϕ were incubated with LXA4, ATL, LXB4, RvD1, or 17(R)-RvD1 at a dose range of 0.01–1 μM for 30 min before other additions (see below).

MTT cell viability assay

Cell viability was ascertained by MTT assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as described [57]. Briefly, 20 μl 2.5 ng/ml MTT was added to each well and incubated for 18 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Supernatants were discarded and 100 μl/well lysis solution (90% isopropanol, 0.5% SDS, 0.04 M NH4Cl, 9.5% H2O) added to each well for 1 h at room temperature. The absorbance was read at 570 nm using a VERSAmax microplate reader and SoftMax Pro software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

ELISA

The concentrations of human TNF (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and human IL-6 and murine TNF (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) were determined by ELISA, according to the manufacturers' instructions. Absorbance (450 nm) was analyzed on a VERSAmax microplate reader using SoftMax Pro software.

Multiplex cytokine assays

The expression profile of a panel of human cytokines (TNF, IL-6, IP-10, IL-7, IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-12p70, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, IFN-α2, GM-CSF, G-CSF, IL-10, IL-8, MCP-1, MIP-1β, MIP-1α, eotaxin, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-β) in mϕ supernatants was measured using the Milliplex human cytokine-premixed 26-plex Immunoassay Kit on a Milliplex Analyzer 3.1 Luminex 200 machine using the corresponding software (Millipore, Chicago, IL, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA purification and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was prepared from mϕ, either unstimulated or stimulated with LPS or live E. coli, using the RNeasy Mini Kit with RNase-free DNase treatment and RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). OD readings were determined for OD260/OD280 and OD260/OD230 using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer and software (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA).

qRT-PCR

Expression levels of selected genes were assessed by qRT-PCR analysis using an ABI 7300 real-time PCR system machine and software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Total mRNA (100 ng) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the RT2 First-strand Kit (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The equivalent of ∼1 ng RNA/well was assayed using the RT2 Profiler PCR array system using a Custom Human RT2 Profiler PCR array (CAPH09575, SABiosciences), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were normalized to three housekeeping controls (GAPDH, β-actin, and hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase 1) and quantified using the ΔΔ comparative threshold method [61], using the analysis tool provided by SABiosciences/Qiagen (http://www.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php).

Metabolic labeling and characterization of WT and lpxM mutant E. coli LPS

The LPS of WT and lpxM mutant E. coli were metabolically labeled during bacterial growth in medium supplemented with [14C]-acetate and then purified. The purified [14C]-LPS was treated at 100°C with 4 N HCl and then 4 N NaOH to release [14C]-FA from LPS. The released [14C]-FA were extracted with CHCl3/CH3OH and recovered in the CHCl3 phase. Samples were then applied to reverse-phase-TLC to separate individual [14C]-FA species. The resolved [14C]-FAs were quantified by densitometry using a Typhoon 8600 scanner (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Infection of human and murine mϕ with live E. coli and assessment of internalization and bacterial killing

Human mϕ were preincubated with vehicle or 17(R)-RvD1 at 1 μM for 30 min (as outlined above) and infected with WT or lpxM mutant E. coli [51] at a MOI of 50:1. Mϕ phagocytosis and bacterial killing of internalized E. coli were assessed by measurement of bacterial CFUs by antibiotic exclusion assay, as described previously [62] and as illustrated in Supplemental Fig. 1A. Briefly, after mϕ were infected with E. coli for 2 h, supernatants were collected to assay for TNF (ELISA) and nonadherent bacteria, and cells were collected to assay for adherent bacteria. For assessment of internalized bacteria, mϕ were treated with antibiotics (ampicillin 100 mg/ml and gentamicin 50 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min to eliminate any remaining extracellular and surface-exposed adherent bacteria, leaving only viable, internalized bacteria for further analyses. The antibiotic-containing medium was then replaced with new medium (RPMI 10% HI FBS) and mϕ incubated for another 2 h to monitor escape or killing of internalized bacteria. At each step, supernatants were removed and mϕ lysed by osmotic rupture in dH2O for 15 min, followed by addition of 2× PBS to preserve bacterial cell-wall integrity, and viable CFUs were determined in supernatants and cell lysates. For pooled analysis of experiments, internalization for each treatment was calculated as percent of associated bacteria; survival of internalized bacteria was calculated as percent of internalized bacteria (see Supplemental Fig. 1A). Murine WT and TLR4-deficient mϕ were preincubated with vehicle or 17(R)-RvD1, as described above, and infected with WT or lpxM mutant E. coli at a 50:1 MOI for 2 h. Levels of murine TNF in supernatants were assessed by ELISA (see above).

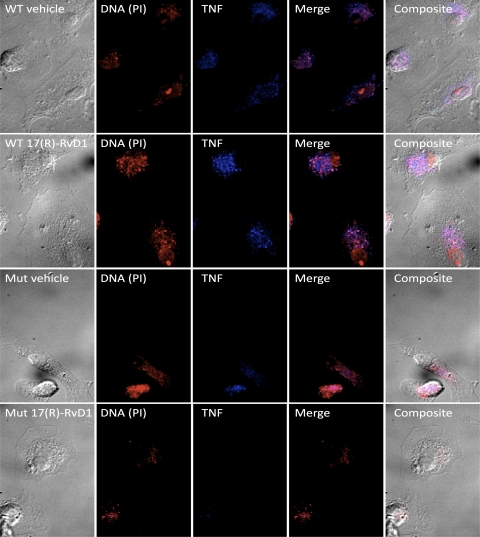

Confocal microscopy

Mϕ were plated on sterile glass 12-mm diameter circles (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in a 24-well, flat-bottom, tissue-culture plate (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in RPMI 10% HI FBS and incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were pretreated with 17(R)-RvD1, stimulated with live E. coli, and subsequently fixed with 4% (v/v) PFA in PBS and stained with PI (Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 700 anti-human TNF (BD Biosciences). Microscopy used a 100× oil immersion lens on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-E (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA), as described previously [63].

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed with biostatistical input from the CHB Clinical Research Program, using the GraphPad Prism 5 software. For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA repeat measures test with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test as post-test was applied. For two-way comparisons between individuals or murine cells, unpaired two-sample t tests were applied. For paired two-way analyses, paired two-tailed t tests were applied. Resulting P values <0.05 (95% confidence interval) were considered significant. Throughout the data figures, significance is as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001.

RESULTS

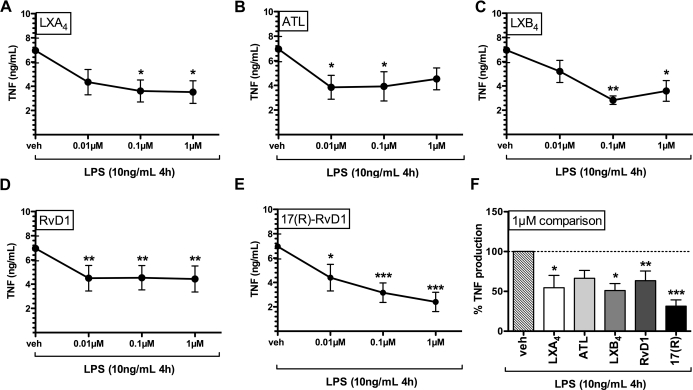

Lx and Rv counter-regulate LPS-induced TNF production in primary human mϕ

We characterized the ability of LXA4, LXB4, RvD1, and their more stable aspirin-triggered epimers, ATL and 17(R)-RvD1, to inhibit LPS-induced TNF production. Primary human mϕ were exposed to vehicle LX or Rv (0.01–1 μM range) and stimulated with LPS (10 ng/mL) for 4 h. Fig. 2 shows effects of LXA4, ATL, LXB4, RvD1, or 17(R)-RvD1 on LPS-induced TNF production. Although all compounds showed significant reduction of TNF compared with vehicle control, the patterns of inhibition for each compound varied depending on dose. Notably, only ATL and both types of RvD1 significantly reduced LPS-induced TNF production at 0.1 μM. No compound cytotoxicity was observed at any concentration tested (MTT assay; data not shown). Compared with vehicle controls, the extent of TNF inhibition at the 1-μM concentration was greatest for 17(R)-RvD1 (∼70% inhibition; Table 1 and Fig. 2F).

Figure 2. LXs and Rvs reduce LPS-induced TNF production in primary human mϕ.

LPS-induced TNF production (4 h stimulation, shown in ng/mL) by primary human mϕ pretreated with increasing doses of LX and Rv is shown (n=6 for all compounds). (A) LXA4, (B) ATL, (C) LXB4, (D) RvD1, and (E) 17(R)-RvD1. (F) Comparison of treatment at 1 μM dose with vehicle expressed as percent TNF induction (compared with vehicle set as 100%). Statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA repeat measures test and Bonferroni's multiple comparison test showed a statistically significant overall effect of treatment compared with vehicle for LXA4, ATL, LXB4, RvD1, and 17(R)-RvD1. Bonferroni post-test confirmed statistically significant differences/individual treatment compared with vehicle control denominated as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001.

Table 1. Comparing % TNF Production with LX/Rv Treatment Production with Vehicle + LPS Controls.

| μM | 0.01 |

0.1 |

1 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | P (veh) | Mean | SEM | P (veh) | Mean | SEM | P (veh) | |

| Vehicle | 100 | – | – | 100 | – | – | 100 | – | – |

| LXA4 | 65.612 | 12.928 | n.s. | 49.898 | 7.131 | P < 0.05 | 54.566 | 15.507 | P < 0.05 |

| ATL | 84.299 | 22.462 | P < 0.05 | 47.434 | 10.105 | P < 0.05 | 51.032 | 8.740 | n.s. |

| LXB4 | 59.969 | 15.755 | n.s. | 61.125 | 18.186 | P < 0.01 | 66.419 | 9.930 | P < 0.05 |

| RvD1 | 65.166 | 11.144 | P < 0.01 | 61.714 | 7.903 | P < 0.01 | 63.450 | 12.174 | P < 0.01 |

| 17(R)-RvD1 | 63.107 | 13.899 | P < 0.05 | 47.081 | 10.415 | P < 0.001 | 31.414 | 7.910 | P < 0.001 |

Percent TNF production after 4 h LPS stimulation in the presence of LXs and Rvs compared with vehicle control (100%) is shown in mean and SEM for 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μM concentrations with P values (95% confidence interval) obtained for Fig. 2 depicted as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001.

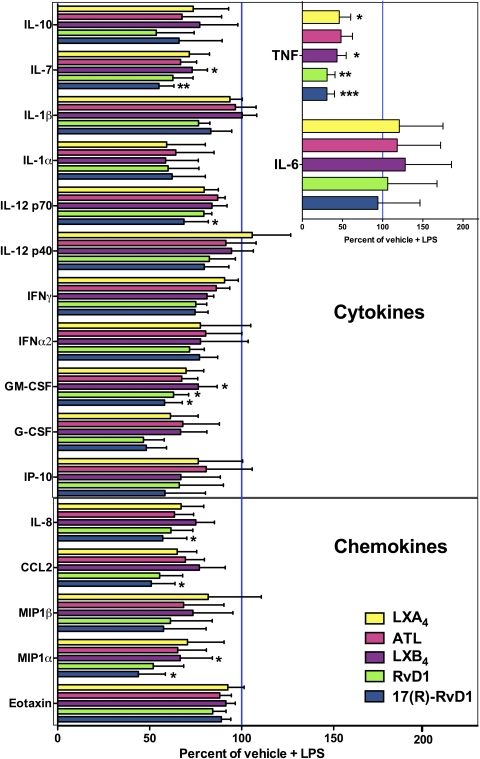

Lx and Rv reduce acute LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine responses in primary human mϕ

To obtain a broader characterization of the actions of LX and Rv on LPS-induced mϕ cytokine induction, we used multiplex cytokine assays. LPS-stimulated mϕ produced TNF, IL-6, IL-10, IL-7, IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-12p70, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, G-CSF, IP-10, IL-8, CCL2, MIP-1-α, MIP-1β, and eotaxin (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 2) but did not produce any detectable levels of IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-β after 4 h or 24 h of stimulation (data not shown). Effects of LXs and Rvs on mϕ cytokine expression profiles demonstrated that 17(R)-RvD1 inhibited cytokine production most consistently and significantly, reducing IL-7, IL-12p70, GM-CSF, IL-8, CCL2, and MIP-1α without altering IL-10 production (Fig. 3; raw data summarized in Supplemental Table 1). All LXs and Rvs tested reduced LPS-induced TNF production consistently without affecting LPS-induced IL-6 production (Fig. 3, inset). Inhibitory effects that were observed at 4 h post-LPS stimulation (Fig. 3) were no longer evident 24 h after stimulation (Supplemental Fig. 2). Mϕ up-regulated TNF and IL-6 mRNA levels in response to LPS stimulation after 4 h (Supplemental Fig. 1B), and LX/Rv-induced reduction of TNF protein production at this time-point (Figs. 2 and 3) did not correspond to alterations in TNF mRNA levels (Supplemental Fig. 1B). These findings might suggest possible post-transcriptional effects of LXs/Rvs on LPS-induced TNF mRNA stability [3], protein secretion [21], or enzymatic processing [64] or possible compound degradation [65]. Levels of IL-6 mRNA were also not altered in the presence of LX and Rv (Supplemental Fig. 1B).

Figure 3. LXs and Rvs reduce acute LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine responses in primary human mϕ.

Effects of LXA4, ATL, LXB4, RvD1, and 17(R)-RvD1 on mϕ LPS-induced production of cytokines after 4 h of stimulation were assessed by multiplex cytokine assay [n=5 for LXA4 and ATL; n=6 for LXB4, RvD1, and 17(R)-RvD1]. The expression profiles of proinflammatory cytokines (IP-10, IL-7, IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-12p70, IL-12p40, IFN-γ, IFN-α2, GM-CSF, and G-CSF), anti-inflammatory IL-10, and chemokines (IL-8, CCL2, MIP-1β, MIP-1α, and eotaxin) are shown. Expression levels of TNF and IL-6 are shown (inset). Values are shown as percent of (vehicle+LPS) control (set as 100%). Statistical analyses by one-way ANOVA repeat measures test and Bonferroni's multiple comparison test are shown as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001. Raw data (mean, sem, and n shown in pg/mL) for each cytokine for 4 h LPS stimulation and each compound are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

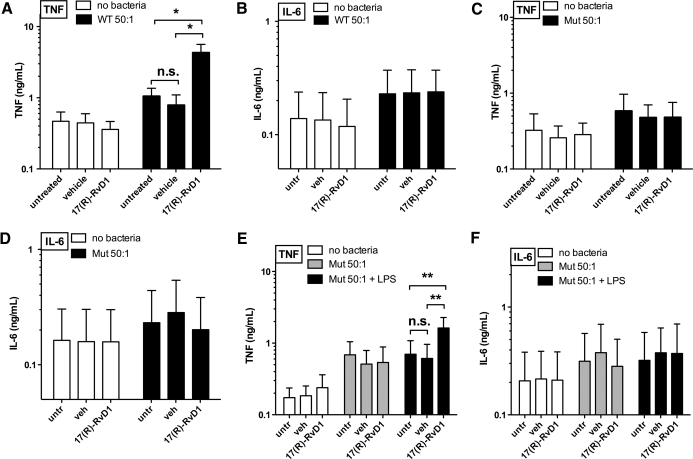

17(R)-RvD1 significantly enhances TNF production by primary human mϕ during incubation with E. coli

As mϕ encounter free and bacteria-associated LPS in vivo [15, 17, 22], we extended our analyses to effects of 17(R)-RvD1 on mϕ TNF production when mϕ were exposed to live WT E. coli rather than to isolated LPS. Remarkably, in marked contrast to the inhibitory effects of 17(R)-RvD1 on TNF production by primary human mϕ exposed to purified LPS, 17(R)-RvD1 significantly increased levels of mϕ WT E. coli-induced TNF production compared with untreated and vehicle controls (Fig. 4A). Concurrent with the selective effects of 17(R)-RvD1 on LPS-induced TNF, but not IL-6 production in mϕ, 17(R)-RvD1 did not alter WT E. coli-induced IL-6 production (Fig. 4B). 17(R)-RvD1 effects on TNF production were also observed when assaying intracellular TNF by confocal microscopy (Fig. 5, top two rows). In keeping with our findings for LPS-induced TNF production, changes in TNF protein were not reflected in TNF mRNA levels from cells treated with 17(R)-RvD1 and infected with WT E. coli (data not shown).

Figure 4. 17(R)-RvD1 significantly enhances TNF production by primary human mϕ during incubation with E. coli.

Effects of 17(R)-RvD1 exposure on (A) TNF and (B) IL-6 protein production by human mϕ infected with WT E. coli for 2 h compared with uninfected cells are shown (ng/ml; n=5). Effects of 17(R)-RvD1 pretreatment on lpxM mutant E. coli-induced TNF (C) and IL-6 (D) production after 2 h stimulation are shown (ng/ml; n=5) for uninfected and lpxM E. coli-infected human mϕ. Actions of 17(R)-RvD1 exposure and infection with lipid A lpxM mutant E. coli for 2 h in the absence or presence of exogenous LPS on (E) TNF production and (F) IL-6 production are shown in ng/ml (n=4). One-way ANOVA repeat measures test and Bonferroni's multiple comparison test showed a statistically significant overall effect of 17(R)-RvD1 treatment compared with vehicle for WT and lpxM mutant E. coli + WT LPS. Bonferroni post-test confirmed statistically significant differences between individual groups as follows: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

Figure 5. 17(R)-RvD1 enhances bacterial internalization and TNF production by human mϕ infected with WT E. coli.

Effects of 17(R)-RvD1 pretreatment and infection with WT and lipid A lpxM mutant E. coli for 2 h by confocal imaging show DNA (PI, red) and anti-TNF (Alexa Fluor 700, blue) staining in mϕ pretreated with 17(R)-RvD1 or vehicle and infected with WT or lipid A lpxM mutant E. coli for 2 h (representative of n=3).

Bacterial and mϕ molecular requirements for enhanced mϕ TNF response in the absence and presence of 17(R)-RvD1

The remarkably different effects of 17(R)-RvD1 on the mϕ TNF response to WT E. coli versus isolated LPS could reflect the impact of other bacterial agonists present in E. coli. Alternatively, differences in requirements for LPS-induced signaling when this signaling occurs as part of more complex mϕ interactions with intact bacteria (containing LPS as a very prominent outer-membrane constituent) might also be involved. To test the latter possibility, we assessed the effects of 17(R)-RvD1 on primary human mϕ TNF production in response to an isogenic lpxM mutant of WT E. coli. In contrast to the WT E. coli strain that produces mainly hexa-acylated LPS with potent TLR4-activating ability, the lpxM mutant produces hypoacylated LPS, which is mainly penta-acylated and has weak TLR4-activating ability [51–53] but comparable growth characteristics and FA composition (Supplemental Fig. 3A and B). TNF production by primary human mϕ pretreated with vehicle or 17(R)-RvD1 and stimulated with WT or lpxM mutant E. coli was assessed. In contrast to its effects of mϕ TNF production with WT E. coli, 17(R)-RvD1 treatment did not exert any effects on TNF production from mϕ stimulated with lpxM mutant E. coli (Fig. 4A and C); this was mirrored by no increase in intracellular TNF in mϕ treated with 17(R)-RvD1 and stimulated with lpxM mutant E. coli (Fig. 5, bottom two rows). In keeping with our previous findings, lpxM mutant E. coli-induced IL-6 production remained unchanged (Fig. 4D). These findings strongly suggest that the presence of potent TLR4-activating hexa-acylated LPS during E. coli stimulation is necessary for the bacterial-induced TNF response of 17(R)-RvD1-treated primary human mϕ.

To further establish the importance of fully acylated LPS and consequently TLR4 signaling for 17(R)-RvD1 treatment to enhance primary human mϕ TNF responses to E. coli, the effects of 17(R)-RvD1 treatment on TNF production in response to lpxM E. coli in the presence of exogenous LPS were assessed. Indeed, ″replenishing″ the lpxM mutant phenotype by adding exogenous, hexa-acylated LPS restored the TNF response in 17(R)-RvD1-treated human mϕ to that of WT-treated cells (Fig. 4E), without affecting concurrent IL-6 production (Fig. 4F). These data further strengthen the hypothesis that 17(R)-RvD1 requires functional signaling through TLR4 to exert its impact on E. coli-induced TNF production in these cells. In the absence of E. coli, human mϕ did not produce detectable levels of extracellular TNF protein in response to LPS after 2 h in the absence or presence of vehicle or 17(R)-RvD1 (data not shown). Thus, TNF-inducing effects of isolated LPS as well as bacteria-associated LPS can be enhanced by exposure of mϕ to 17(R)-RvD1, provided LPS is seen by the mϕ at the same time that the mϕ are exposed to/interacting with intact bacteria.

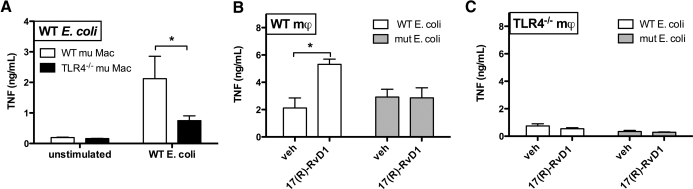

The importance of LPS acylation in the mϕ responses observed strongly suggests that 17(R)-RvD1 receptor engagement acts on signaling pathways downstream of MD-2/TLR4 in primary human mϕ stimulated with E. coli. To test this hypothesis more directly, we compared the TNF-inducing actions of WT and lpxM mutant E. coli on WT versus TLR4-deficient murine mϕ in the presence or absence of 17(R)-RvD1. As shown in Fig. 6A, the TNF response to WT E. coli was largely dependent on mϕ TLR4, as WT murine mϕ produced significantly more TNF in response to WT E. coli compared with TLR4-deficient murine mϕ. WT murine mϕ treated with 17(R)-RvD1 showed similar response patterns to primary human mϕ when stimulated with E. coli, showing the characteristic increase in TNF production in response to WT, but not lpxM mutant, E. coli (Fig. 6B). In contrast, TLR4-deficient murine mϕ treated with 17(R)-RvD1 did not exhibit any increase in TNF production, when stimulated with WT or lpxM mutant E. coli (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that E. coli-induced TNF production is largely TLR4-dependent and, as the TLR4-deficient mϕ are not deficient in any other TLRs expressed by murine mϕ [2, 66], that 17(R)-RvD1 effects on mϕ TNF production require functional signaling through TLR4.

Figure 6. 17(R)-RvD1-dependent enhancement of TNF production by mϕ requires hexa-acylated LPS and functional TLR4.

Murine WT and TLR4-deficient mϕ were infected with WT or lpxM mutant E. coli for 2 h, and TNF production in supernatants assessed by ELISA is shown as ng/mL (n=3). (A) Statistical analysis by unpaired two-tailed t test shows a significant increase in TNF production from WT compared with TLR4-deficient mϕ stimulated with WT E. coli; *P < 0.05. (B) TNF production by WT murine mϕ treated with vehicle or 17(R)-RvD1 in response to WT and lpxM mutant E. coli is shown. Statistical analysis by paired two-tailed t test shows a significant increase in TNF production with 17(R)-RvD1 treatment in cells simulated with WT E. coli; *P < 0.05. (C) TNF production by TLR4-deficient murine mϕ treated with vehicle or 17(R)-RvD1 in response to WT and lpxM mutant E. coli is shown.

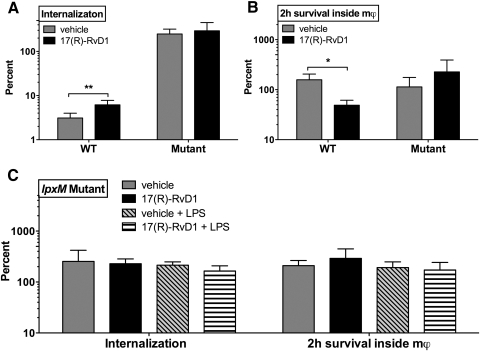

17(R)-RvD1 enhances phagocytic killing of WT E.coli

The stimulation of mϕ proinflammatory (i.e., TNF) responses by 17(R)-RvD1 during exposure of the mϕ to live E. coli raised the possibility that 17(R)-RvD1 could also affect the fate of the bacteria during their interactions with the mϕ. To explore this possibility, we made use of an antibiotic exclusion assay (Supplemental Fig. 1A and ref. [62]) to enumerate viable E. coli CFUs from primary human mϕ after external application of antibiotics and enumeration of viable intracellular bacteria after further incubation (2 h) in the absence of antibiotics. Treatment with 17(R)-RvD1 significantly increased internalization and decreased intracellular survival of WT E. coli compared with vehicle control (Fig. 7A and B). In contrast, assessment of bacterial internalization and intracellular survival of lpxM mutant E. coli revealed no significant effects of 17(R)-RvD1 treatment (Fig. 7A and B), suggesting that these effects of 17(R)-RvD1 may also be dependent on hexa-acylated, LPS-triggered TLR4 signaling. Interestingly, addition of LPS to lpxM E. coli in the presence of 17(R)-RvD1 did not rescue internalization or killing of internalized bacteria by human mϕ (Fig. 7C). This suggests distinct requirements for the LPS/TLR4-dependent TNF phenotype, which can be complemented by addition of free LPS in trans, compared to increased internalization and killing induced by 17(R)-RvD1 in human mϕ, which cannot be complemented in this manner. Although the lpxM mutant E. coli did not exhibit a growth defect compared with the WT strain and displayed comparable FA composition ratios, as assessed by TLC (Supplemental Fig. 3A and B), it should be noted that the interactions of the mutant versus WT bacteria are different with untreated primary human mϕ (Supplemental Fig. 3D and E), complicating interpretation of the apparently different effects of 17(R)-RvD1 treatment on mϕ internalization and killing of WT versus lpxM E. coli.

Figure 7. 17(R)-RvD1 enhances phagocytic killing of E. coli in a manner dependent on hexa-acylated LPS.

Effects of 17(R)-RvD1 and infection with WT E. coli for 2 h on bacterial internalization (2 h+45 min) and intracellular survival (2 h+45 min+2 h) are shown comparing lipid A lpxM mutant and WT E. coli. (A) Percent internalization and (B) intracellular survival of bacteria (WT, n=6; lpxM mutant, n=5) are shown. (C) Percent internalization and intracellular survival of lpxM mutant in the presence or absence of exogenous WT LPS are shown in vehicle and 17(R)-RvD1-treated mϕ. Internalization and intracellular survival of bacteria comparing vehicle and 17(R)-RvD1 are analyzed by paired two-tailed t test (*P<0.05 and **P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized the actions of LXs and Rvs on interactions of primary human mϕ with LPS and E. coli, demonstrating for the first time that these modulatory actions are distinct for isolated LPS and whole E. coli, based on the following key observations: 1) The proresolving mediators each inhibited LPS-induced TNF protein production without affecting corresponding mRNA in primary human mϕ. 2) LXs and Rvs generally inhibited expression of most proinflammatory cytokines by primary human mϕ without affecting LPS-induced IL-6 or IL-10 protein levels; 17(R)-RvD1 treatment significantly inhibited IL-7, IL-12p70, GM-CSF, IL-8, CCL2, and MIP-1α production. 3) 17(R)-RvD1 significantly increased E. coli-induced TNF production in human mϕ; this was dependent on the presence of fully acylated LPS in combination with bacteria, as well as functional TLR4 signaling. 4) Exposure of human mϕ to 17(R)-RvD1, prior to E. coli stimulation, increased internalization and phagocytic killing of E. coli. 5) Increased internalization and phagocytic killing of E. coli by mϕ may require the presence of hexa-acylated LPS as an integral part of the bacterial membrane.

We are the first to report that LXA4, ATL, LXB4, RvD1, and 17(R)-RvD1 reduce LPS-induced TNF production by primary human mϕ, in keeping with recent studies demonstrating that LXA4 reduced LPS-induced TNF production by murine RAW264.7 [42–44, 67] and rat pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells [42–44, 67]. In addition, we show for the first time that 17(R)-RvD1 reduces LPS-induced production of IL-7, IL-12p70, GM-CSF, IL-8, CCL2, and MIP-1α production in primary human mϕ without altering IL-6 or IL-10 production. If our novel observations for the actions of LXs and Rvs on LPS- and E. coli-induced cytokine production by primary human mϕ established in this study are applicable to in situ responses in humans, this observed phenotype would reduce inflammatory responses to free LPS and preserve cytokine-based resolution signals, including IL-6 and IL-10, thereby enhancing resolution of free, LPS-driven inflammation. The relatively higher efficacy and potency of 17(R)-RvD1 may reflect its relative resistance to metabolic enzymes and consequently, greater stability [65]. Inhibition of LPS-induced TNF production was noted with as little as 0.1 μM. The greatest extent of inhibition was noted at 1 μM, a concentration selected for the study of 17(R)-RvD1 actions on mϕ interactions with E. coli, and that may be achieved pharmacologically [41].

In marked contrast to our results on its effects on free LPS, 17(R)-RvD1 induced a significant increase in WT E. coli-induced primary human mϕ TNF production. By assessing the effects of 17(R)-RvD1 treatment of WT and TLR4-deficient murine mϕ stimulated with WT or lpxM mutant E. coli, we can conclude that 17(R)-RvD1 exerted its impact on mϕ TNF responses to E. coli in a manner dependent on the presence of fully acylated LPS in combination with bacteria and functional TLR4 signaling. Although differences in LPS acylation could also affect other molecular interactions of the bacteria with mϕ, the ability of added WT (TLR4-activating) LPS to stimulate TNF production by 17(R)-RvD1-treated mϕ when added together with lpxM E. coli (but not when added alone), strongly argues that the role of LPS in this setting is as a TLR4 agonist.

An intriguing and important question raised by our findings is how the context of LPS-induced TLR4 signaling (i.e., whether triggered by LPS alone or in conjunction with bacterial–mϕ interactions) so radically changes the effects of 17(R)-RvD1 on mϕ signaling. One could imagine that the localization of LPS-driven TLR4 signaling or the simultaneous activation of other signaling pathways by other bacterial agonists could influence the impact of 17(R)-RvD1 on LPS/TLR4-dependent mϕ signaling. Alternatively, it is also possible that the uptake of bacteria leads to cointernalization of the added purified LPS. Future studies using an alternative TLR4 agonist, such as HMGB-1, would allow further conclusions about whether LPS engagement of TLR4 in particular or TLR4 activation per se is required for 17(R)-RvD1-mediated effects on primary human mϕ.

Equally important is whether the enhancement of mϕ TNF production by 17(R)-RvD1 in response to live E. coli leads to, or is a marker of, the enhanced antibacterial phenotype of the 17(R)-RvD1-treated human mϕ that we observed, which is consistent with previous studies showing that the related compound RvE1 increases phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs and E. coli in human and murine mϕ and enhances clearance of E. coli in mice in vivo [68]. In contrast to 17(R)-RvD1 effects on TNF induction, 17(R)-RvD1-driven enhancement of internalization and phagocytic killing of WT E. coli by human mϕ could not be recapitulated by presenting lpxM mutant E. coli in conjunction with exogenous WT LPS provided in trans. These observations suggest that Rv enhancement of mϕ internalization and phagocytic killing may require WT hexa-acylated lipid A present as an integral part of the outer membrane of the bacteria. Of note, the observed baseline differences in the interactions of WT and mutant bacteria with untreated mϕ (Supplemental Fig. 3) need to be considered when interpreting these results.

In summary, our results demonstrate that 17(R)-RvD1 differentially modulates primary human mϕ responses to LPS, depending on the context in which LPS is presented to the mϕ. To our knowledge, we are the first to describe this phenomenon of differential actions of 17(R)-RvD1 on human mϕ responses to purified LPS and to LPS presented in the context of live E. coli, i.e., during a setting modeling infection. We speculate that from a teleological perspective, the divergent actions of 17(R)-RvD1 on free and bacteria-bound LPS may reflect the differing demands in the local settings in which the body must confront bacterial LPS. During infection, mϕ might encounter free LPS more frequently (e.g., shed from bacteria) if, for example, bacteria have already been killed by host defense mechanisms, at which point further TNF production might be harmful, and resolution may be favored.

In the context of whole bacteria, however, RvD-induced enhancement of rapid mϕ TNF production may amplify clearance of bacteria through rapid induction of the inflammatory response, aided by the influx of PMN and additional monocytes from the circulation that can differentiate into mϕ. This model may be consistent with a recent study using a murine peritonitis model, demonstrating that inflammatory mϕ exhibit high phagocytic activity and produce high levels of LPS-induced TNF and CCL2 early during inflammation, while ″satiated″ resolution-type mϕ display lower phagocytic activity and down-regulate LPS-induced TNF and CCL2 production and emigrate to the lymphatic tissues for clearance during later stages of inflammation [69]. In this context, we recognize that we have no direct evidence at this point linking the 17(R)-RvD1-dependent increased TNF response with enhancement in phagocytic killing, as has been shown for E. coli and Candida albicans phagocytosis by human PMN treated with RvD1 or RvE1, respectively [49, 70]. Future work should explore the effects of 17(R)-RvD1 on mϕ responses to a range of microbes, including additional GNB species, as well as endogenous danger-associated molecular patterns such as HMGB-1, which activate mϕ via TLR4 [71].

A great deal of biopharmaceutical development has focused on anti-inflammatory agents, which can provide clinical benefit but which also comes at the expense of enhanced susceptibility to infection [72, 73]. In contrast, our results suggest that the actions of 17(R)-RvD1 on human primary mϕ are such that bacterial clearance is enhanced, but inflammatory responses to shed LPS are reduced. Together with the ability of ATL to induce expression of BPI in human mucosal epithelia [74], these properties render eicosanoids and docosanoids (and their precursors AA and DHA, respectively) attractive candidates for biopharmaceutical development as agents to enhance bacterial clearance while reducing chronic inflammation. Indeed, DHA, eicosapentaenoic acid and congeners are currently in human clinical trials for chronic inflammation as seen in inflammatory bowel disease [75, 76]. Our present results suggest that LXs and Rvs and their metabolically stable analogs also hold promise in the adjunctive treatment of human GNB infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this project was provided by a Dana Human Immunology Award (to O.L. and E.C.G.), the Defense Advanced Projects Agency (DARPA; to E.C.G. and O.L.), the Greene Fund (to E.C.G.), and NIH R21 HL089659-01A1 (to E.C.G. and O.L.). C.J.M. acknowledges the support of the Thrasher Foundation. The laboratory of O.L. is supported by NIH RO1 AI067353 and an American Recovery and Reinvestmant Act NIH Administrative Supplement 3R01AI067353-05S1. Work in the C.N.S. laboratory was supported in part by NIH (Bethesda, MD, USA), grant nos. R01GM038765 and P01GM095467 (to C.N.S.). C.P. and O.L. acknowledge support from the Dartmouth Center for Medical Countermeasures Pilot Project. We thank all adult volunteers who donated blood and Drs. K. Kronforst and K. Nathe for phlebotomy. We thank biostatistician Dr. Leslie Kalish (CHB Clinical Research Program) for critical review of statistical analyses. We thank Dr. Christian Raetz (Duke University Medical School, Durham, NC, USA) for providing the WT and isogenic lpxM mutant strains of E. coli and Dr. Douglas Golenbock (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA) for providing us with WT and TLR4-deficient murine mϕ.

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

- 17(R)-RvD1

- 17(R)-resolvin D1; 7S,8R,17R-trihydroxy-4Z,9E,11E,13Z,15E,19Z-docosahexaenoic acid

- AA

- arachidonic acid

- ATL

- aspirin-triggered lipoxin; 15-epi-lipoxin A4; (5S,6R,15R)-5,6,15-trihydroxy-7,9,13-trans-11-cis-eicosatetraenoic acid

- BPI

- bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein

- CHB

- Children′s Hospital Boston

- DHA

- docosahexaenoic acid

- FA

- fatty acid

- GNB

- Gram-negative bacteria

- HI

- heat-inactivated

- HMGB-1

- high-mobility group box 1

- IP-10

- IFN-inducible protein 10

- LT

- leukotriene

- LX

- lipoxin

- LXA4

- lipoxin A4; 5(S),6(R),15(S)-trihydroxyeicosa-7-trans-9-trans-11-cis-13-trans-tetraenoic acid

- LXB4

- lipoxin B4; 5S,14R,15S-trihydroxy-6E,8Z,10E,12E-eicosatetraenoic acid

- mϕ

- macrophage

- MD-2

- myeloid differentiation protein 2

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- Rv

- resolvin

- RvD1

- resolvin D1; 7S,8R,17S-trihydroxy-4Z,9E,11E,13Z,15E,19Z-docosahexaenoic acid

- RvD2

- 7S,16R,17S-trihydroxy-4Z,8E,10Z,12E,14E,19Z-docosahexaenoic acid

- RvE1

- resolvin E1; 5S,12R,18R-trihydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid

- STZ

- serum-treated zymosan

- TLC

- thin-layer chromatography

AUTHORSHIP

C.D.P. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; C.J.M. assisted with experimental set up; C.N.S. provided vital training in handling of compounds, configuration of Fig. 1, and intellectual input and contributed to manuscript preparation, J.P.W. performed LPS extraction and TLC experiments and provided intellectual input; and E.C.G. and O.L. provided funding and intellectual input.

DISCLOSURE

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1. Horwood N. J., Page T. H., McDaid J. P., Palmer C. D., Campbell J., Mahon T., Brennan F. M., Webster D., Foxwell B. M. (2006) Bruton′s tyrosine kinase is required for TLR2 and TLR4-induced TNF, but not IL-6, production. J. Immunol. 176, 3635–3641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoshino K., Takeuchi O., Kawai T., Sanjo H., Ogawa T., Takeda Y., Takeda K., Akira S. (1999) Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the LPS gene product. J. Immunol. 162, 3749–3752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Palmer C. D., Mutch B. E., Workman S., McDaid J. P., Horwood N. J., Foxwell B. M. (2008) Bmx tyrosine kinase regulates TLR4-induced IL-6 production in human macrophages independently of p38 MAPK and NFκB activity. Blood 111, 1781–1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Serhan C. N., Chiang N., Van Dyke T. E. (2008) Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 349–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Serhan C. N., Savill J. (2005) Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1191–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schwab J. M., Chiang N., Arita M., Serhan C. N. (2007) Resolvin E1 and protectin D1 activate inflammation-resolution programmes. Nature 447, 869–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duffield J. S., Hong S., Vaidya V. S., Lu Y., Fredman G., Serhan C. N., Bonventre J. V. (2006) Resolvin D series and protectin D1 mitigate acute kidney injury. J. Immunol. 177, 5902–5911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Godson C., Mitchell S., Harvey K., Petasis N. A., Hogg N., Brady H. R. (2000) Cutting edge: lipoxins rapidly stimulate nonphlogistic phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Immunol. 164, 1663–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitchell S., Thomas G., Harvey K., Cottell D., Reville K., Berlasconi G., Petasis N. A., Erwig L., Rees A. J., Savill J., Brady H. R., Godson C. (2002) Lipoxins, aspirin-triggered epi-lipoxins, lipoxin stable analogues, and the resolution of inflammation: stimulation of macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils in vivo. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 2497–2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reville K., Crean J. K., Vivers S., Dransfield I., Godson C. (2006) Lipoxin A4 redistributes myosin IIA and Cdc42 in macrophages: implications for phagocytosis of apoptotic leukocytes. J. Immunol. 176, 1878–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gordon S. (2003) Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gordon S., Martinez F. O. (2010) Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 32, 593–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salkowski C. A., Neta R., Wynn T. A., Strassmann G., van Rooijen N., Vogel S. N. (1995) Effect of liposome-mediated macrophage depletion on LPS-induced cytokine gene expression and radioprotection. J. Immunol. 155, 3168–3179 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zarbock A., Ley K. (2009) Neutrophil adhesion and activation under flow. Microcirculation 16, 31–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jonsson S., Musher D. M., Chapman A., Goree A., Lawrence E. C. (1985) Phagocytosis and killing of common bacterial pathogens of the lung by human alveolar macrophages. J. Infect. Dis. 152, 4–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klein R. D., Su G. L., Schmidt C., Aminlari A., Steinstraesser L., Alarcon W. H., Zhang H. Y., Wang S. C. (2000) Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein accelerates and augments Escherichia coli phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages. J. Surg. Res. 94, 159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Poirier K., Faucher S. P., Beland M., Brousseau R., Gannon V., Martin C., Harel J., Daigle F. (2008) Escherichia coli O157:H7 survives within human macrophages: global gene expression profile and involvement of the Shiga toxins. Infect. Immun. 76, 4814–4822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hattori M., Taylor T. D. (2009) The human intestinal microbiome: a new frontier of human biology. DNA Res. 16, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sivick K. E., Mobley H. L. (2010) Waging war against uropathogenic Escherichia coli: winning back the urinary tract. Infect. Immun. 78, 568–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rolhion N., Darfeuille-Michaud A. (2007) Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 13, 1277–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith A. M., Rahman F. Z., Hayee B., Graham S. J., Marks D. J., Sewell G. W., Palmer C. D., Wilde J., Foxwell B. M., Gloger I. S., Sweeting T., Marsh M., Walker A. P., Bloom S. L., Segal A. W. (2009) Disordered macrophage cytokine secretion underlies impaired acute inflammation and bacterial clearance in Crohn′s disease. J. Exp. Med. 206, 1883–1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andersen B. M., Skjorten F., Solberg O. (1979) Electron microscopical study of Neisseria meningitidis releasing various amounts of free endotoxin. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. [B] 87B, 109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marshall J. C., Walker P. M., Foster D. M., Harris D., Ribeiro M., Paice J., Romaschin A. D., Derzko A. N. (2002) Measurement of endotoxin activity in critically ill patients using whole blood neutrophil dependent chemiluminescence. Crit. Care 6, 342–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levy O., Teixeira-Pinto A., White M. L., Carroll S. F., Lehmann L., Wypij D., Guinan E. (2003) Endotoxemia and elevation of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22, 978–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fallach R., Shainberg A., Avlas O., Fainblut M., Chepurko Y., Porat E., Hochhauser E. (2010) Cardiomyocyte Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in heart dysfunction following septic shock or myocardial ischemia. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48, 1236–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tracey K. J., Fong Y., Hesse D. G., Manogue K. R., Lee A. T., Kuo G. C., Lowry S. F., Cerami A. (1987) Anti-cachectin/TNF monoclonal antibodies prevent septic shock during lethal bacteremia. Nature 330, 662–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cristofaro P., Opal S. M. (2006) Role of Toll-like receptors in infection and immunity: clinical implications. Drugs 66, 15–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bahador M., Cross A. S. (2007) From therapy to experimental model: a hundred years of endotoxin administration to human subjects. J. Endotoxin Res. 13, 251–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cross A. S., Opal S. M., Palardy J. E., Drabick J. J., Warren H. S., Huber C., Cook P., Bhattacharjee A. K. (2003) Phase I study of detoxified Escherichia coli J5 lipopolysaccharide (J5dLPS)/group B meningococcal outer membrane protein (OMP) complex vaccine in human subjects. Vaccine 21, 4576–4587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cross A. S. (2010) Development of an anti-endotoxin vaccine for sepsis. Subcell. Biochem. 53, 285–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cross A. S., Opal S., Cook P., Drabick J., Bhattacharjee A. (2004) Development of an anti-core lipopolysaccharide vaccine for the prevention and treatment of sepsis. Vaccine 22, 812–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gea-Banacloche J. C., Opal S. M., Jorgensen J., Carcillo J. A., Sepkowitz K. A., Cordonnier C. (2004) Sepsis associated with immunosuppressive medications: an evidence-based review. Crit. Care Med. 32, S578–S590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akashi S., Nagai Y., Ogata H., Oikawa M., Fukase K., Kusumoto S., Kawasaki K., Nishijima M., Hayashi S., Kimoto M., Miyake K. (2001) Human MD-2 confers on mouse Toll-like receptor 4 species-specific lipopolysaccharide recognition. Int. Immunol. 13, 1595–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shimazu R., Akashi S., Ogata H., Nagai Y., Fukudome K., Miyake K., Kimoto M. (1999) MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 189, 1777–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borish L. C., Steinke J. W. (2003) 2. Cytokines and chemokines. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111, S460–S475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bystrom J., Evans I., Newson J., Stables M., Toor I., van Rooijen N., Crawford M., Colville-Nash P., Farrow S., Gilroy D. W. (2008) Resolution-phase macrophages possess a unique inflammatory phenotype that is controlled by cAMP. Blood 112, 4117–4127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jones S. A. (2005) Directing transition from innate to acquired immunity: defining a role for IL-6. J. Immunol. 175, 3463–3468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mosser D. M., Edwards J. P. (2008) Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 958–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Levy B. D., Clish C. B., Schmidt B., Gronert K., Serhan C. N. (2001) Lipid mediator class switching during acute inflammation: signals in resolution. Nat. Immunol. 2, 612–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wu S. H., Liao P. Y., Yin P. L., Zhang Y. M., Dong L. (2009) Elevated expressions of 15-lipoxygenase and lipoxin A4 in children with acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 115–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Morris T., Stables M., Hobbs A., de Souza P., Colville-Nash P., Warner T., Newson J., Bellingan G., Gilroy D. W. (2009) Effects of low-dose aspirin on acute inflammatory responses in humans. J. Immunol. 183, 2089–2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kure I., Nishiumi S., Nishitani Y., Tanoue T., Ishida T., Mizuno M., Fujita T., Kutsumi H., Arita M., Azuma T., Yoshida M. (2010) Lipoxin A(4) reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in macrophages and intestinal epithelial cells through inhibition of NF-{κ}B activation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 332, 541–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang L., Wu P., Jin S. W., Yuan P., Wan J. Y., Zhou X. Y., Xiong W., Fang F., Ye D. Y. (2007) Lipoxin A4 negatively regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced differentiation of RAW264.7 murine macrophages into dendritic-like cells. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 120, 981–987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhou X. Y., Wu P., Zhang L., Xiong W., Li Y. S., Feng Y. M., Ye D. Y. (2007) Effects of lipoxin A(4) on lipopolysaccharide induced proliferation and reactive oxygen species production in RAW264.7 macrophages through modulation of G-CSF secretion. Inflamm. Res. 56, 324–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Krishnamoorthy S., Recchiuti A., Chiang N., Yacoubian S., Lee C. H., Yang R., Petasis N. A., Serhan C. N. (2010) Resolvin D1 binds human phagocytes with evidence for proresolving receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1660–1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ohira T., Arita M., Omori K., Recchiuti A., Van Dyke T. E., Serhan C. N. (2010) Resolvin E1 receptor activation signals phosphorylation and phagocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3451–3461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. El Kebir D., Jozsef L., Pan W., Wang L., Petasis N. A., Serhan C. N., Filep J. G. (2009) 15-epi-lipoxin A4 inhibits myeloperoxidase signaling and enhances resolution of acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 180, 311–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Seki H., Fukunaga K., Arita M., Arai H., Nakanishi H., Taguchi R., Miyasho T., Takamiya R., Asano K., Ishizaka A., Takeda J., Levy B. D. (2010) The anti-inflammatory and proresolving mediator resolvin E1 protects mice from bacterial pneumonia and acute lung injury. J. Immunol. 184, 836–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Spite M., Norling L. V., Summers L., Yang R., Cooper D., Petasis N. A., Flower R. J., Perretti M., Serhan C. N. (2009) Resolvin D2 is a potent regulator of leukocytes and controls microbial sepsis. Nature 461, 1287–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Canny G., Levy O., Furuta G. T., Narravula-Alipati S., Sisson R. B., Serhan C. N., Colgan S. P. (2002) Lipid mediator-induced expression of bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI) in human mucosal epithelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 99, 3902–3907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Somerville J. E., Jr., Cassiano L., Bainbridge B., Cunningham M. D., Darveau R. P. (1996) A novel Escherichia coli lipid A mutant that produces an antiinflammatory lipopolysaccharide. J. Clin. Invest. 97, 359–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vorachek-Warren M. K., Ramirez S., Cotter R. J., Raetz C. R. (2002) A triple mutant of Escherichia coli lacking secondary acyl chains on lipid A. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14194–14205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reynolds C. M., Raetz C. R. (2009) Replacement of lipopolysaccharide with free lipid A molecules in Escherichia coli mutants lacking all core sugars. Biochemistry 48, 9627–9640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Teghanemt A., Zhang D., Levis E. N., Weiss J. P., Gioannini T. L. (2005) Molecular basis of reduced potency of underacylated endotoxins. J. Immunol. 175, 4669–4676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cui W., Morrison D. C., Silverstein R. (2000) Differential tumor necrosis factor α expression and release from peritoneal mouse macrophages in vitro in response to proliferating gram-positive versus gram-negative bacteria. Infect. Immun. 68, 4422–4429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Feldmann M. (2002) Development of anti-TNF therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 364–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. József L., Zouki C., Petasis N. A., Serhan C. N., Filep J. G. (2002) Lipoxin A4 and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxin A4 inhibit peroxynitrite formation, NF-κ B and AP-1 activation, and IL-8 gene expression in human leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13266–13271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Palmer C. D., Rahman F. Z., Sewell G. W., Ahmed A., Ashcroft M., Bloom S. L., Segal A. W., Smith A. M. (2009) Diminished macrophage apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation after phorbol ester stimulation in Crohn′s disease. PLoS ONE 4, e7787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kurt-Jones E. A., Popova L., Kwinn L., Haynes L. M., Jones L. P., Tripp R. A., Walsh E. E., Freeman M. W., Golenbock D. T., Anderson L. J., Finberg R. W. (2000) Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat. Immunol. 1, 398–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yu M., Wang H., Ding A., Golenbock D. T., Latz E., Czura C. J., Fenton M. J., Tracey K. J., Yang H. (2006) HMGB1 signals through Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR2. Shock 26, 174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bustin S. A. (2000) Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 25, 169–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cortés G., Wessels M. R. (2009) Inhibition of dendritic cell maturation by group A Streptococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 200, 1152–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nathe K. E., Parad R., Van Marter L. J., Lund C. A., Suter E. E., Hernandez-diaz S., Boush E. B., Ikonomu E., Gallington L., Morey J. A., Zeman A. M., McNamara M., Levy O. (2009) Endotoxin-directed innate immunity in tracheal aspirates of mechanically ventilated human neonates. Pediatr. Res. 66, 191–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Moss M. L., Jin S. L., Becherer J. D., Bickett D. M., Burkhart W., Chen W. J., Hassler D., Leesnitzer M. T., McGeehan G., Milla M., Moyer M., Rocque W., Seaton T., Schoenen F., Warner J., Willard D. (1997) Structural features and biochemical properties of TNF-α converting enzyme (TACE). J. Neuroimmunol. 72, 127–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sun Y. P., Oh S. F., Uddin J., Yang R., Gotlinger K., Campbell E., Colgan S. P., Petasis N. A., Serhan C. N. (2007) Resolvin D1 and its aspirin-triggered 17R epimer. Stereochemical assignments, anti-inflammatory properties, and enzymatic inactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9323–9334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liew F. Y., Xu D., Brint E. K., O′Neill L. A. (2005) Negative regulation of Toll-like receptor-mediated immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 446–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wu S. H., Liao P. Y., Dong L., Chen Z. Q. (2008) Signal pathway involved in inhibition by lipoxin A(4) of production of interleukins induced in endothelial cells by lipopolysaccharide. Inflamm. Res. 57, 430–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Oh S. F., Pillai P. S., Recchiuti A., Yang R., Serhan C. N. (2011) Pro-resolving actions and stereoselective biosynthesis of 18S E-series resolvins in human leukocytes and murine inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 569–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schif-Zuck S., Gross N., Assi S., Rostoker R., Serhan C. N., Ariel A. (2011) Saturated-efferocytosis generates pro-resolving CD11b low macrophages: modulation by resolvins and glucocorticoids. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 366–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Haas-Stapleton E. J., Lu Y., Hong S., Arita M., Favoreto S., Nigam S., Serhan C. N., Agabian N. (2007) Candida albicans modulates host defense by biosynthesizing the pro-resolving mediator resolvin E1. PLoS ONE 2, e1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Van Zoelen M. A., Yang H., Florquin S., Meijers J. C., Akira S., Arnold B., Nawroth P. P., Bierhaus A., Tracey K. J., van der Poll T. (2009) Role of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4, and the receptor for advanced glycation end products in high-mobility group box 1-induced inflammation in vivo. Shock 31, 280–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sfikakis P. P. (2010) The first decade of biologic TNF antagonists in clinical practice: lessons learned, unresolved issues and future directions. Curr. Dir. Autoimmun. 11, 180–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Arnold T. M., Sears C. R., Hage C. A. (2009) Invasive fungal infections in the era of biologics. Clin. Chest Med. 30, 279–286 (vi.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Palmer C. D., Guinan E., Levy O. (2011) Deficient expression of baclericidal permeabllhty-increasing protein immunocompromised hosts: translational potential of replacement therapy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rahimi R., Mozaffari S., Abdollahi M. (2009) On the use of herbal medicines in management of inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review of animal and human studies. Dig. Dis. Sci. 54, 471–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ruggiero C., Lattanzio F., Lauretani F., Gasperini B., Andres-Lacueva C., Cherubini A. (2009) Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and immune-mediated diseases: inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 15, 4135–4148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.