Abstract

The relevance and importance of research for understanding policy processes and influencing policies has been much debated, but studies on the effectiveness of policy theories for predicting and informing opportunities for policy change (i.e. prospective policy analysis) are rare.

The case study presented in this paper is drawn from a policy analysis of a contemporary process of policy debate on legalization of abortion in Indonesia, which was in flux at the time of the research and provided a unique opportunity for prospective analysis. Applying a combination of policy analysis theories, this case study provides an analysis of processes, power and relationships between actors involved in the amendment of the Health Law in Indonesia. It uses a series of practical stakeholder mapping tools to identify power relations between key actors and what strategic approaches should be employed to manage these to enhance the possibility of policy change.

The findings show how the moves to legalize abortion have been supported or constrained according to the balance of political and religious powers operating in a macro-political context defined increasingly by a polarized Islamic-authoritarian—Western-liberal agenda. The issue of reproductive health constituted a battlefield where these two ideologies met and the debate on the current health law amendment became a contest, which still continues, for the larger future of Indonesia. The findings confirm the utility of policy analysis theories and stakeholder mapping tools for predicting the likelihood of policy change and informing the strategic approaches for achieving such change. They also highlight opportunities and dilemmas in prospective policy analysis and raise questions about whether research on policy processes and actors can or should be used to inform, or even influence, policies in ‘real-time’.

Keywords: Health policy, policy analysis, abortion, Indonesia, theory

KEY MESSAGES.

Application of policy analysis theories and stakeholder mapping tools accurately predicted the likelihood of change on abortion policy in Indonesia.

Policy analysis theories and stakeholder mapping tools are useful to inform strategic approaches for achieving such change but academic researchers are not best placed to implement policy-change strategies.

Introduction

Policy analysis theories and tools for understanding policy change

Theories and analysis of health policy have blossomed over the past 15 years and continue to evolve, as the 2008 special edition of Health Policy and Planning (volume 23, issue 5) richly demonstrates. There are numerous theories elaborating the complexities of the policy processes and stages from Easton’s linear and mysterious ‘black box’ of policy making (Easton 1965) through diffusion theories (Mintrom 1997; Berry 2007) and ‘advocacy coalitions’ (Sabatier 1999) describing more iterative influences and process, to the contemporary consensus that health policy is a complex series of incremental and iterative cycles, feedback loops and influences (Lush et al. 2003; Walt 2004; Walt et al. 2004; Buse et al. 2005). The processes and conditions necessary to facilitate policy change have also been explored, from getting an issue onto the political agenda (Hall 1976 in Buse et al. 2005) to understanding when a ‘window of opportunity’ for change emerges (Kingdon 1984).

Understanding the different dimensions of ‘power’ and how it is exercised by a broadening network of actors is widely recognized as central to understanding policy decision-making and therefore the potential for decision-making. Power is widely understood as pluralist (Dahl 1961; Buse et al. 2005; Lukes 2005), though elitist power of authoritarian regimes is also recognized (Heywood 1999). Power can be exercised through individual agency and/or the power of structures and organizations (Giddens 1984). Further, the power of non-state decision-makers, like the media, is increasingly acknowledged (Lukes 2005), and the involvement of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and advocacy groups in policy processes has become increasingly formalized (Buse and Walt 2000; de Leeuw 2001). Related to this, theories of ‘interconnectedness’ (Bordieu 1983) have developed that seek to understand the networking between different groups and individuals towards a common goal—so called ‘policy networks’ (Marsh 1998; Walt et al. 2003) and ‘policy communities’ (Buse et al. 2005).

Attempts to map key actors, their connections and influences in the policy process led to the development of tools that enable us to understand the personalities and politics of a wide range of stakeholders who are interested in or will be affected by policy change (Blair et al. 1996 in Varvaskovsky and Brugha 2000; Reich and Cooper 2001; Roberts et al. 2004). These tools allow us to map out the stakeholders (policy actors) according to their relative power, influence and networks, and determine how to strategically manage them in order to play up or ward off their influence around a particular policy issue. Such tools represent a step from theoretical analysis towards the development of operational steps to proactively pursue policy change. As such, they are used not only by academics, but also by NGOs and interest or lobby groups. Challenges abound, however, in attempting this step from analysis to action and there is little in the published literature on this, though its dearth has been noted (Buse 2008). Some theoretical work exists on the challenges facing reformers, who tend, by definition, not to be favoured by the status quo and its institutions (Swank 2002; Oliver 2006). Most case-study applications of policy analysis have been historical (for example, Trostle et al. 1999; Shretta et al. 2001); few discuss actual strategies used by actors to leverage their position (Gonzalez-Rosetti and Bossert 2000, analysing South American countries, is an exception), and the few contemporary analyses that exist seek to understand the power and influence that explains contemporary decisions and positions, but do not seek to analyse how a change could be made (e.g. Schneider 2002).

In recognition of these gaps, this paper describes an Indonesian study that was undertaken to explore the driving forces behind a contemporary process of policy debate on legalization of abortion in Indonesia, to analyse the positions of key stakeholder groups, to assess the extent to which a window of opportunity was available for policy change and to identify what strategic approaches would be necessary to achieve a policy change. As with many academic studies, there was no funding to develop and implement strategies suggested by the identified approaches. Nevertheless, subsequent events allowed us to test the predictive power of the agenda-setting and stakeholder-mapping tools. Based on the findings—and limitations—of this study, therefore, the paper reflects on the utility and challenges of using policy analysis to predict and to influence contemporary health policy processes.

Indonesia was chosen as a case study for testing these policy theories because, at the time of the research, the debate on legalization of abortion was beginning to be taken up in public by a wider range of actors than previously. It represented a unique opportunity to analyse the power and policy positions of stakeholders in a policy debate that was unfolding.

Abortion legislation in Indonesia

A diversity of legal traditions which exist in parallel in Indonesia leads to ambiguity in the legal status of abortion (Bowen 2003; Burns 2004). Both Criminal Law [Kitab Undang-undang Hukum Pidana (KUHP) Articles 346–349] (Republic of Indonesia, undated), modelled on the Dutch colonial government, and Shari’a Law forbid abortion, but under the Health Law (Law 23/1992, Article 15) it is permitted to save the woman’s life. In addition, some clinics will provide abortions in the case of contraceptive failure because it is then deemed to be a health service failure and not the fault of the woman who had taken reasonable steps to prevent unwanted pregnancy, although clinics require women to bring their husbands and prove that they are married (Republic of Indonesia 1992; Bedner 2001). An explanatory note to the law specifies that the health worker must be a qualified obstetrician/gynaecologist.

The punishment for illegal abortion is also inconsistent across the different laws. The Health Law states that punishment for abortion is 15 years' of imprisonment, with a fine of 500 million rupiah (about £28 000) (Article 8) (Republic of Indonesia 1992). Indictments under this clause of the Health Law are based on the Criminal Code (KUHP), but this states that the punishment for illegal abortion is 5.5 years' imprisonment for the perpetrator (Article 348) and 4 years' for a woman inducing her own abortion (Article 346) (Republic of Indonesia, undated). Furthermore, the 2004 Medical Practice Law provides for a maximum sentence of 3 years' imprisonment (Republic of Indonesia 2004a). In the 1970s, an ‘understanding’ was reached by medical professionals, on the advice of the Chief Justice of the High Court, that abortions could be performed to preserve a woman’s life or health (Utomo et al. 1982; Hull et al. 1993). Since the early 1970s, there have been continuous attempts in Indonesia to reform the abortion law. The most recent debates have drawn in political, religious and social groups.

The views of abortion according to different strands of Islam and Islamic law are complex and often exacerbated by wider political concerns (Bowen et al. 1997). There are two main sects within Islam: the Shiite/Shia and the Sunni. The Shiites have historically deemed abortion illegal after implantation except to save the mother’s life, but important changes have emerged over the past two decades. Although in general abortion is discouraged, there are now many examples—most recently from Iran—where religious rulings and legislation have permitted abortions for a broader range of conditions including serious foetal abnormalities and serious social or economic hardship at various stages during the pregnancy (Hedayat et al. 2006).

Indonesia is a majority Sunni population who adhere to the teachings of elected Islamic scholars. There are four schools of thought in Sunni Islam and the Shafi’I school is prominent in Indonesia (and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, Southern Arabia and parts of East Africa). This school holds that abortions may be permitted, if for good reason, up to 120 days of pregnancy when ‘ensoulment’ is deemed to occur (Bowen 1997; Maguire 2001; Outka and Brockopp 2002; Aksoy 2005). Nevertheless, since none of the schools acknowledge a hierarchical clergy, there are considerable variations in beliefs and practices within one school. In Indonesia the leadership is divided into three principal sources: (1) the religious leaders (ulama or kyai) who work for the Ministry of Religious Affairs and other government departments; (2) the independent religious leaders and scholars who have individual followers; and (3) the major Islamic organizations. Three organizations have a significant role in influencing and changing attitudes towards policy: the Majelis Ulama Indonesia (MUI, Indonesian Religious Leaders Council), the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and the Muhammadiyah.

MUI is a consultative body to the government working closely with the Ministry of Religious Affairs, issuing fatwas on social issues, including abortion, and representing several Muslim organizations including the NU and Muhammadiyah (Kaptein 2004). In 1983 and 1992 the MUI declared that abortion was absolutely prohibited (haram). Nonetheless, the Muslim community is divided on this issue. The NU is the largest Muslim organization in Indonesia (about 40 million members, mostly rural), and often progressive including on reproductive health issues. Some of its leaders condone abortion, albeit reluctantly, as ‘just cause’ when pregnancy endangers a woman’s health, while others accept abortion as long as it occurs before ensoulment, i.e. before 120 days of pregnancy (Sciortino et al. 1996; Candland and Nurjanah 2004). NU has recommended that abortions be conducted in emergency situations when the pregnancy endangers a mother’s life, and that it be considered for cases of rape and incest—a view supported by NU’s Women’s Organization and by a number of scholars from Islamic universities who argue that unwanted pregnancies endanger the lives of mothers (Baramuli 2004). The Muhammadiyah is the most conservative of the main organizations; an independent modernist organization, it aims to restore the purity of Islamic teaching. Although its membership is quite small, it is highly influential because of its national network of schools and hospitals and its access to mass media. It opposes abortion on the grounds that it destroys valued life (Dzuhayatin 2006).

The ambiguity of the legality of abortion (judicial and religious), and the severity of punishment, leads to widespread confusion and reluctance among medical practitioners to perform abortions. Study data indicate that ambiguity also leads to an inconsistent application of the law, corruption and extortion. Consequently there are high levels of clandestine abortions resulting in a maternal mortality rate that is the highest in the sub-region: 334 deaths per 100 000 women compared with 10/100 000 in Singapore, 60/100 000 in Philippines and 50/100 000 in Thailand (Ministry of Health and World Health Organization 2003; UNDP 2007).

Aims, concepts and methods

The aim of this study was two-fold:

To document the relative power and influence of the key actors in order to understand the context in which abortion policy decisions are made;

To apply known policy analysis frameworks to test their usefulness for predicting the future direction of an abortion policy in a political climate currently in flux.

We employed a policy analysis approach drawing on concepts from two models. First, Kingdon’s concept of a convergence of three ‘streams’ (problem recognition, development and diffusion of policy alternatives, and political context) to achieve a ‘window of opportunity’ for a change in policy. In the Indonesian context we considered both immediate-historical and contemporary contexts relevant to the Health Reform Bill. Problem recognition explored how much consensus there was that the high levels of maternal mortality, including from unsafe abortion, was a problem, and how it was framed (as a health and/or rights issue). The political will affecting the development and diffusion of differing solutions required more analysis since a range of possible responses emerged. Second, Walt and Gilson’s framework investigating actors, processes and contexts was employed to better understand the factors influencing the three streams (Walt 1994; Walt and Gilson 1994; Kingdon 1995). We also used stakeholder analysis frameworks and tools to analyse the power, networking and political will of key actors in order to clearly recognize both the promoters and detractors in the political stream (Majchrzak 1984; Brugha and Varvasovsky 2000).

A total of 158 in-depth key informant interviews with 98 respondents were conducted in ‘Bahasa Indonesia’ by CS between August 2004 and January 2006. Respondents were selected through purposive and snowball sampling. Interviews with about half of respondents were tape-recorded; where permission was not given, extensive notes were taken which were verified with the respondent. All interviews were then transcribed and analysed in Bahasa Indonesia; they were only translated into English for inclusion in the written analysis. The range of respondents is shown in Table 1. In addition to a wide spectrum of key informants, media and document analysis and participant observation at political events were conducted through the study period. A personal reflective diary checked personal bias in conducting interviews and the stakeholder analysis. The data were analysed qualitatively and key emerging themes were consolidated in a code frame that was checked and refined through application.

Table 1.

Interviews conducted, by respondent type

| Interviewees | No. |

|---|---|

| Executives: presidential staff and cabinet members | 3 |

| Legislatives (Parliament Members who are members of Commissions) | 26 |

| Indonesia Forum of Parliamentarians on Population & Development (IFPPD) | 4 |

| Politicians from liberal parties (PDIP, Demokrat, Golkar, PKB) | 17 |

| Politicians from conservative parties (PAN, PPP, PKS) | 9 |

| Ministry of Health and bureaucrats | 4 |

| National Family Planning Coordination Board | 3 |

| Progressive religious groups | 5 |

| Hard-line religious groups | 3 |

| Health and women’s NGOs | 16 |

| Professional medical bodies | 18 |

| Law enforcement/judicial | 4 |

| Media/journalists | 3 |

| Academics | 7 |

| Other key informants (donors, community groups, medical practitioners, influential individuals in public life etc.) | 36 |

| TOTAL | 158 |

In addition to receiving information from key stakeholders, a system of triangulation was used to establish the validity of information. This process involved cross-checking information from one or more sources, either through interviews or official documents, to validate a statement made by a respondent. Therefore, most information here was obtained from two or more sources. In instances where information conflicted, further enquiry was made through additional interviews and document analysis to clarify the issue. In addition, a respondent validation was conducted to confirm the interpretive validity of the findings. More than half of the interviewees were shown a summary of the analysis and asked to give feedback on a one-on-one basis.

Context and process: analysis of the passage of the Health Reform Bill

The contextual and process analysis was based on analysis of documents, literature review and key informant interviews.

Historical analysis; the first health Bill: abortion as a health and rights issue

The first legal concession to abortion appeared in the 1999 ratification of the International Convention Against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, by President B J Habibie (Law 39/1999, Republic of Indonesia 1999). The new national law described abortion to save a mother’s life and a court decision to pass the death sentence as the only two permissible exceptions to the right to life. It was only after President Megawati was inaugurated in 2001 that abortion began to be taken up as a health, rather than a criminal, issue. When President Megawati came to power in July 2001 there were high hopes among women’s rights advocates and she certainly gave more attention to women’s issues, including tabling the first bill to amend the Health Law. The draft health bill allowed that ‘Qualified, safe, and responsible pregnancy cessation should be performed based on the emergency situation justified by authorized health personnel’ (Chapter IX, article 63, section 3). It was presented as part of a much wider Bill on Health including maternal health, with the maternal mortality rate (MMR) widely acknowledged as unacceptably high. Views differed, however, on the extent to which abortion contributed to the MMR, with estimates ranging from 11% (Department of Health 1995) to 50% (Director General of Community Health in the Jakarta Post 2000). Consequently, views differed on the solutions to the high MMR, with many preferring improvements to antenatal care and delivery care, education and increased family planning, over legalization of safe abortion services.

During President Megawati’s term, wide consultation was held on the draft Bill encompassing NGOs, religious and professional organizations as well as government institutions. The Health Commission presented the final draft, with academic supporting papers, to Parliament, who, after a period of internal discussion, backed it and proposed the Bill to Government to secure a Presidential Decree to pass it into law.

In parallel, however, President Megawati had to manage powerful opponents. Although her party had majority seats in the parliament, it was not enough to provide a strong, unconditional support and she therefore had to form a coalition cabinet (Mydans 2001). Recognizing the constraints of this arrangement, President Megawati embarked on constitutional reform to increase Presidential powers and restructure Parliament. This included endorsing a new regulation reforming the processes necessary to make and to amend bills (Law 30/2004, Republic of Indonesia 2004b). President Megawati’s term as president came to an end in 2004 before the Health Bill gained its presidential decree. She was not re-elected and the regulation that changed the Bill-making procedures was to stall the progress of the Health Bill under her successor.

Contemporary analysis; the second Bill’s passage: abortion becomes an ideological battleground

In 2004, when the fieldwork for this study began, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, a retired military general, had become the first president to be elected directly by voters. He won a large majority on the platform of a secular state with an international and commercial relations stance. His election, the sound defeat of the Islamic parties and his appointment of four women to his cabinet, one of whom became the Minister for Health, once again brought hopes for women’s rights. Despite a strengthened role of the President vis à vis parliament following constitutional reform, Yudhoyono was from a small party and therefore still potentially vulnerable to negative reactions in Parliament. Therefore he too sought to satisfy the different political interests by forming a large coalition cabinet, including many hard-line religious parties in opposition to his own (Zenzie 1999; Effendy 2004; President of Indonesia 2004).

To make things worse his presidency had to cope with a series of national disasters which seriously detracted from his reform agenda, including the devastating tsunami affecting Aceh (December 2004), suicide bombers in Bali (September 2002 and October 2005) and a series of natural and man-induced disasters in Java throughout 2005–06. Events on the macro-political stage further exacerbated the religious, political and ethnic divides in an already fractious political and social fabric. The fall-out from the events of 9/11 were huge and ongoing: the war on terror, further bombings in Bali and London, the war in Iraq, the publication in a Danish newspaper of a series of cartoons about Mohammed, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and more. All these events served to escalate tensions in Indonesia between Muslims in Indonesia and the West, as manifest in extensive polarized newspaper coverage at the time that was examined as part of the media/document review for the study. So, when by mid-2005 the Health Bill amendment was back in Parliament, it was coloured by the increasingly polarized macro-political climate:

“This is Western propaganda covered in humanitarian aid. One of the proofs is that ICPD provides US$15 million to fund reproductive health and reproductive rights campaigns. Do they give this for free? Is this a real humanitarian act?…this is nothing but Western trick to promulgate their secular concept of freedom.” (Member of Religious Group, Interviewee #45)

“By using the word ‘safe abortion’ instead of ‘legal abortion’ the Westerners poison our society with their secular ideas. Solving our problems the Western way means separating religion from life.” (Member of Religious Group, Interviewee #40)

The amendment of the Health Law to liberalize abortion was thus portrayed as an encroachment of Western ideology incompatible with Islamic values; a critical battlefield in the ideological war for the destiny of Indonesia, with Parliament apparently reluctant to act in the face of religious opposition:

“If [Parliamentarians] are really serious in their effort to strive for women’s reproductive rights, the legislative can use its authority to push the government to take further action about the health bill.” (NGO member, Interviewee #59)

As a direct counter to the Health Bill, an Anti-Pornography Bill was proposed in February 2006 which sought to impose mandatory clothing restrictions on women, curfews on their movement and criminalize their sexual liberties. It was listed, together with the Health Bill, in the National Legislation Programme for 2005–09 (Department of Laws and Human Rights 2008), provoking fierce debate and mass demonstrations from a whole cross-section of Indonesian society concerned by the Bill’s perceived clamp down on women’s rights. Proponents of the Anti-Pornography Bill claim ‘… this draft law is being deliberated because we are trying to protect women and children, not to criminalize them …’ (Amidhan, leader of Religious Leaders Council (MUI) and member of National Commission on Human Rights, cited in Jakarta Post, March 2006). Its opponents, who favour the Health Bill, accused the Anti-Pornography Bill of discriminating against Indonesia’s diverse cultures and traditions tantamount to an act of treason against the state ideology Pancasila (an embodiment of the principles of an independent Indonesian state formulated by Sukarno in 1945) and the 1945 constitution which protects the country’s many cultures (Effendy 2004; Gillespie 2007).

Analysis of power and linkage of key actors and use of stakeholder mapping tools

It is against the preceding contextual backdrop that the study sought to analyse the power and linkage of key actors, map their positions (both in terms of how they framed the problem and their views on the solutions), determine whether a window of opportunity existed for change and inform strategic approaches to achieve this.

Presidents Megawati and Yudhoyono had both come to power on a similar secular, pro-reform platform, but both needed to appoint inclusive cabinets to ensure broad parliamentary support, and this meant that the powerful religious parties in Parliament were able to wield increasing influence. Furthermore, macro-political events heightened the tension between ‘Western’ and ‘Islamic’ values, increasing the political bargaining power of the religious anti-reformist factions in Parliament and appearing to give them an upper hand.

Since President Soeharto’s regime (1965–98), Indonesia has maintained a secular state distancing Islam from politics, though there are a number of powerful Islamic parties in Parliament. There are seven major parties in Indonesia, which can be roughly divided according to their predominant ideology: secular or Islam. In an Indonesian context ‘liberal’ represents a pluralist, egalitarian and non-sectarian outlook, while ‘conservative’ represents a more sectarian, explicitly pro-Muslim ideology actively engaged in proselytising, as the basis for state action (Zenzie 1999). The religious outlooks of the seven major political parties on this spectrum are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Religious perspectives of Indonesia’s seven major political parties

Pro-reformists

It is perhaps no surprise that the parties’ religious outlook approximated to their official views on the abortion ‘problem’. The more liberal political parties can be generally described as pro-reformist. The PDI-P (led by former President Megawati) talked of the amendment in a rational, secular way:

“This amendment will accommodate protection of reproductive rights and reproductive health, including safe termination of pregnancy which has been profoundly discussed and debated. The objective is to have a solid policy ground on the national and local level. Reproductive health needs to be integrated in the health services, especially in health centres.” (PDI-P Representative and member of Health Commission IX, Interviewee #12)

The position of the Democratic Party (Demokrat) is similar, though they were careful to explain that the amendment was about regulating unsafe abortion to minimize maternal deaths, not to liberalize abortion:

“The high MMR is attributed to unsafe pregnancy termination due to lack of information and access to health care services. Abortion is not only the responsibility of medical professionals. Data shows that most abortions were performed by unskilled persons such as midwives and dukun (traditional healers). This is the reason why we have such a high number of unsafe abortions. This is what we want to regulate in the health bill. Thus this health bill is not created to liberalize abortion.” (Democratic Party Representative and member Women’s Empowerment Commission VIII, Interviewee #22)

The moderate parliamentary groups enjoyed an advantage in weight of numbers in parliament and its commissions. Table 2 indicates the numbers from each of the seven main parties on the three key health-related commissions.

Table 2.

Party representatives in the abortion-relevant Commissions, Parliament 2005–09

| Commissions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Political parties | VIII (Women’s empowerment) | IX (Health) | X (Education, youth) |

| Golkar | 11 | 11 | 12 |

| Indonesian Democratic Party-Struggle (PDIP) | 10 | 9 | 9 |

| National Awakening Party (PKB) | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| United Development Party (PPP) | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Democratic Party | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| National Mandate Party (PAN) | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Other small parties | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Total members | 45 | 44 | 47 |

These numbers alone boded well for passage of the amendment. In addition, pro-reformist women/health NGOs, professional bodies, progressive religious groups and academia have coalesced, led by the Women’s Health Foundation (YKP). Analysis of key stakeholders and interviews with them revealed that the political influence of YKP is high because of its connections, through blood and marriage ties, with high-level individuals at the Supreme Court, police force, the Attorney General, and the House of Representatives. Pro-reformists have worked both formally and informally to promote the Health Bill by using personal networks and links, and fostering collaboration with the media.

Despite the fact that the reform Bill had behind it a well-connected organization like YKP, and through it influential elite politicians, as well as the support of the liberal political parties in Parliament, the outcome of the Bill’s passage was not guaranteed since the anti-reform lobby was vocal and proactive.

Anti-reformists

The anti-reformist, religiously conservative parties expressed strong opposition of the amendment on the grounds that it actively legalized abortion which they oppose on religious and moral grounds:

“This is nothing but a cowardly euphemism—hiding behind subtle words such as ‘to save a woman from unsafe abortion’. This bill is clearly advocating abortion.” (PKS Representative, Health Commission IX, Interviewee #26)

“There are articles in the health bill which give a chance for people to abort and reproduce without considering religious aspects and society ethics.…these articles may precipitate free sex. It is okay to reproduce but marital status should be the requirement.” (Media reference: PPP Representative, quoted Suara Merdeka, 14th September 2005)

Being politically, legally and socially powerful, and with direct influence on policy makers, it was the religious leaders who held a pivotal role in the abortion policy debate. The MUI is the highest Islamic consultative body to the government. Its membership includes prominent religious leaders as well as government officials from the Ministry of Religious Affairs and representatives of Muslim organizations. When MUI issues a fatwa (religious order), the majority of Indonesian Muslims tend to follow it. The MUI has repeatedly declared abortion haram (forbidden) except to save the mothers’ life and in 2000 issued a fatwa to this effect (Masyhuri 2002). As noted earlier, the hostile macro-political climate has also been exploited by the religious-political opposition, who have mobilized popular media against the Bill and held up the abortion clause as evidence of corrupting Western influences.

Changing balance of power

In November 2006, after consultations with medical experts and progressive religious groups during discussions on the present Health Bill, MUI released a fatwa that abortion is allowed in pregnancies in the case of rape as long as the pregnancy is less than 40 days. With this fatwa MUI issued an explanation to society that abortion can be performed and be considered legitimate provided there is adherence to certain conditions and religious requisites. This began to open the door to reform with one of Indonesia’s most influential religious advisory groups.

At the end of 2006 when the interviews were completed, the pro- and anti-reformists appeared closely matched, each facing a tough fight to prevail. Victory hinged upon the decisions of the strategies in each camp. Having identified the key pro- and anti-reformists, a stakeholder mapping exercise was then undertaken to identify key approaches to prospectively managing these factions.

Stakeholder mapping and strategy development

As noted in the methods section, the study findings (narrative and stakeholder mapping) were verified with more than half of respondents. The stakeholder mapping that was conducted therefore represents a triangulated interpretation of the relative power and influence of key stakeholders. The two tables below summarize findings on how actors viewed the abortion problem (Table 3), whether they supported legislation (the Health Bill and its abortion clause) as the solution and their relative influence and power (Table 4).

Table 3.

Stakeholders’ views and priority on abortion issue

| Key actors | Views on abortion | Priority on issue |

|---|---|---|

| Executives | Do not acknowledge abortion as a pressing health problem | Low |

| Legislatives | Health and human rights issue | High |

| IFPPD | Health and human rights issue | High |

| Moderate political parties | Health and human rights issue | High |

| Conservative political parties | Health issue | Moderate |

| Ministry of Health and bureaucrats | Health issue | Moderate |

| National Family Planning Coordination Board (BKKBN) | Health issue | Moderate |

| Religious groups | Recognize abortion as a problem, but oppose the practice based on moral and religious reasons | On and off – depend on situation; no lobbying, act when needed |

| Health and women NGOs | Health and human rights issue | High |

| Professional bodies | Health issue and human rights issue | High |

| Private practices | Health issue and human rights issue | High |

| Law enforcement/Judicative | Recognize that the law is ambiguous | Moderate |

| Media | Health issue and human rights issue | On and off – depend on situation |

| Academia | Health and human rights issue | Moderate |

| Others | Span spectrum | Span spectrum |

IFPPD = Indonesia Forum of Parliamentarians on Population & Development.

Table 4.

Key actors’ standpoints and influence/power

| Current position on proposed solution |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Key actors | Health Bill in general | Abortion issues specifically | Influence/power |

| Executives | Neutral | Ambivalent | +/+++ |

| Legislatives | Strongly supportive | Modestly supportive | ++/++ |

| IFPPD | Strongly supportive | Strongly supportive | ++/+ |

| Liberal political parties | Supportive | Spans spectrum | ++/++ |

| Conservative political parties | Modestly supportive | Oppose | ++/++ |

| Ministry of Health and bureaucrats | Supportive | Ambivalent | +/++ |

| Family Planning Coordination Board | Modestly supportive | Ambivalent | +/− |

| Hard-line religious groups | Neutral | Strongly oppose | +++/+ |

| Progressive religious groups | Strongly supportive | Strongly supportive | +++/+ |

| Health and women NGOs | Strongly supportive | Strongly supportive | +++/− |

| Professional bodies | Strongly supportive | Predominantly supportive | +/− |

| Private practices | Strongly supportive | Predominantly supportive | −/− |

| Law enforcement/judicative | Modestly supportive | Modestly supportive | −/− |

| Media | Neutral | Opportunistically opposed | +++/− |

| Academia | Supportive | Modestly supportive | −/− |

| Others | Supportive | Spans spectrum | +/− |

IFPPD = Indonesia Forum of Parliamentarians on Population & Development.

Table 3 indicates that most key actors recognize that widespread unsafe abortion is a serious problem. Most see abortion purely as a health problem which means they often expect it to have a health service solution (an expanded family planning programme was seen by many as the answer to the problem). Fewer, though still a surprisingly large number, see the issue as both a health and a human rights one, and therefore give more weight to the proposed legislation as a probable solution.

If Table 4 is compared with Table 3 a number of correlations are evident. Actors who regard abortion as a human rights issue are, in general, in favour of the legislative amendment liberalizing access to abortion. The three groups who see abortion primarily as a health issue are ambivalent or opposed to the abortion clause, though largely supportive of the Bill itself. In fact no group opposes the Bill itself, though some are neutral, and only three groups are actively opposed to abortion. Nevertheless, as the previous analysis of the anti-reformists has also shown, these are powerful groups: vocal, hard-line religious leaders, the media and conservative parties in Parliament.

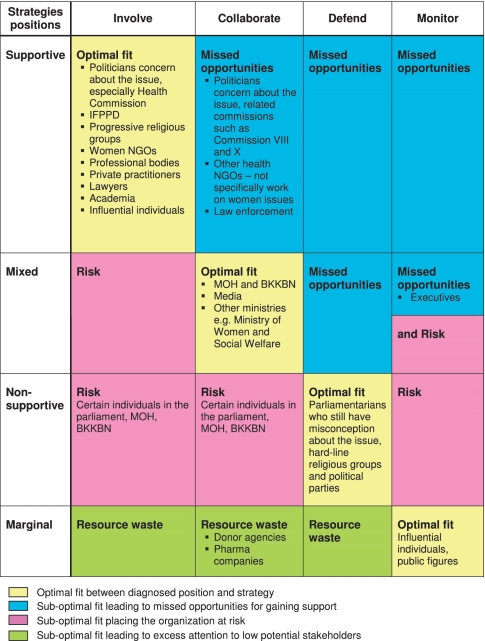

Following our mapping of stakeholders, analysis of the key-informant interviews and assessment of each actor’s perspectives on the problem and solutions and their relative power and influence, we placed the stakeholders on an ‘optimal fit model’ which determined how much and what kind of attention should be paid to stakeholders (Blair et al. 1996, adapted by Varvasovsky and Brugha 2000). This is shown in Figure 2 from the perspective of wanting to support the Health Bill. For example, pro-Bill campaigners could galvanize support through actively involving progressive religious groups, individual politicians concerned about women’s health and individual lawyers who are supportive of the Bill. Ministries with a mixed position on the Health Bill represent opportunities for collaboration; for example, discussions on the benefits of the Bill compared with other options. Those groups with a non-supportive position towards the Bill—such as hard-line religious groups—need to be defended against, in other words opposed, by campaigners for the Bill, to expose their differences and prejudices; any attempt at collaboration or more active involvement with these groups represents a risk. Finally, those who are marginal in the debate on the Bill (including various influential public figures and role models) should be monitored, and if they start to express a strong opinion for or against the Bill, they would then be either defended against or drawn into campaign collaboration or involvement.

Figure 2.

Strategies for managing stakeholders to support the Health Bill

A window of opportunity? What happened next?

Our application of the policy and stakeholder analysis tools suggested that a window of opportunity to pass the Bill did exist. Careful work of pro-reformists with the MUI and progressive religious groups, together with consolidating the support of the popular media, had the potential to turn public and Parliamentary opinion in the Bill’s favour—providing that the spectrum of actors and their delicate balance could be effectively managed, and in particular that the influence of hard-line religious leaders could be curbed.

The time-limited academic analysis ended here; the practical development and application of strategies should then have begun, but as with too many research projects there was no funding available to properly follow-up on the findings of the stakeholder analysis and the strategic approaches resulting from this study. The findings were presented to several international and national conferences and meetings on reproductive rights and abortion. In addition CS met many members of activist groups to share findings and discuss strategic approaches. In general, though, the academic researchers were not privy to the politicking and negotiations occurring between the pro-reformist groups, and could not work with the reformists for the further 3 years it took before the Health Bill was finally passed.

After ongoing media and professional spars between the pro- and anti-reformists, the anti-reformists seemed to take the upper hand in late 2008 when parliament approved the Anti-Pornography Bill which became law on 30 October 2008. Eight factions in the parliament approved, two walked out and two individuals from Golkar party (one of the eight factions who approved) also walked out, and widespread demonstrations took place. The passing of this opposing bill, however, appeared to rekindle efforts by the reformists to step-up and co-ordinate their networking and lobbying, and on Monday, 14 September 2009, the Health Bill was approved by the legislative body and passed into Law (enacted on 13 October 2009). The reproductive health (including abortion) component appears under articles 71–77 while the penalty component appears under article 194. The Bill approved still bears a lot of controversial, discriminative articles towards women and retains some ambiguity. For example, article 75 (2a) and (2b) mentions that abortions are permitted only under medical emergency detected in early pregnancy and in rape cases, indicating that medical emergency and rape will be governed in a separate government regulation 75(3). Article 76 outlines the conditions under which an abortion is permissible and indicates it can take place for any reasons up to six weeks after the first day of last menstruation except under medical emergency, and shall be under consent of the woman and her husband, except in a rape case. Article 77 stated that the government shall protect and prevent women from having non-qualified, unsafe and irresponsible abortion, and also abortions which oppose religious norms and laws/regulations provisions. Article 194 stated that performing abortion not under circumstances as laid down in article 75 (2a) and (2b) is criminalized with a maximum penalty of 10 years prison and 1 billion rupiah. YKP (the women’s foundation) and its coalitions plan to go to Mahkamah Konstitusi (Constitutional Court) to review the controversial and discriminative articles before the law can be implemented through government regulations.

Conclusions and reflections on the use and utility of policy and stakeholder tools

Clearly, the debate about incorporating reproductive rights, including abortion, into the health bill in Indonesia became a religion- and culture-driven debate and not simply a data-driven public health or rights debate. Continuing political debts have played an important role in the policy development of successive presidents and allowed religious parties to wield considerable influence. Our findings show how the moves to legalize abortion have been supported or constrained according to the balance of political and religious powers operating in a macro-political context increasingly defined by a polarized Islamic-authoritarian—Western-liberal agenda. Pro-abortion forces advocated a larger democratic and libertarian agenda for a profound break from the authoritarian past, whereas those opposed to abortion aligned their strategy to a religious authoritarian agenda. The issue of reproductive health therefore constituted a battlefield where these two ideologies met and the debate on the current health law amendment became a contest, which still continues, for the larger future of Indonesia.

In a setting where a substantive policy issue is debated as a function of political debt and credit, compounded by religious and moral pronouncements, a number of challenges are thrown down for researchers engaged in prospective policy analysis, in particular: in such settings what is the purpose of academic policy analysis; should academics be engaging in prospective analysis that overtly seeks to change policy; if so, how can they do it effectively?

What is the point of academic policy analysis?

A rigorous, academic analysis of complex policy processes and the comparison of situations and contexts are important for two reasons. First, in order for anyone to influence the policy process, and the resulting decisions, we need to understand it. Academic analysis allows a refinement of research frameworks and tools, over long years of application in multiple contexts, which deepens our understanding of policy processes and where and how interventions can most effectively be made. In practice, there are few published case studies applying political analysis theories in ‘real time’, that would allow constructive reflection on existing theories and tools. Our study confirmed the usefulness of a combined theoretical approach. The Walt–Gilson framework for analysing policy process, context and actors informed the assessment needed to apply the Kingdon model of convergence of three streams to assess the likelihood of policy change. Our findings confirmed the predictive ability of this model. Second, lessons can be learned across contexts and issues. For example, our findings regarding the critical role the YKP women’s foundation played in connecting the political actors, religious leaders and influential media is important and has resonance for many other settings.

Should academics engage in prospective analysis and if so, how?

A particular challenge faces prospective policy researchers rather than, for example, academics involved in research on a specific medical or health issue which can be presented as ‘evidence’ to influence a policy. Policy research that seeks to understand the political process itself in order to influence it may therefore be seen as overtly attempting to challenge the status quo, an aim not readily accepted by powerful policy decision-makers.

In our Indonesia case, the study identifies approaches for managing stakeholders toward a consensus and alignment of positions. These indicate with whom (e.g. progressive religious groups) a particular approach (e.g. involvement in pro-change discussions) should be used. Such knowledge may enable key policy advocates to develop strategies for action to effectively use potential windows of opportunity in the policy-making process. To be truly effective, however, the advocates themselves need to be involved in the development of strategies. To secure their engagement, academics need to be linked into the advocate/activist scene. This blurring of academic–advocacy boundaries may, in turn, raise questions of impartiality. If academics actively engage with stakeholders (either by working with them to identify strategies or ‘handing-on’ their findings to act on) do they jeopardize academia’s role as an ‘impartial’ researcher, which is what may provide them with credibility in the first place? Buse (2008) argues that there may in fact be an ethical argument that policy researchers and others should be involved in actively changing policy if this upholds internationally agreed goals such as the Millennium Development Goals. This might be a more acceptable role for ‘think-tank’ researchers rather than academic researchers.

The findings from this study suggest that policy analysis theories and stakeholder mapping tools can be applied to predict the likelihood of policy change and inform the strategic approaches for achieving such change. The jury is still out on whether researchers engaged in such research can—or should themselves—make the step from analysis to action and the partiality that this would inevitably be seen to entail.

Funding

No funding was received to undertake this research.

Ethical clearance

Ethical clearance was obtained from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Ethics Review Committee and from the Indonesian authorities in the Ministry of Health.

References

- Aksoy S. Making regulations and drawing up legislation in Islamic countries under conditions of uncertainty, with special reference to embryonic stem cell research. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2005;31:399–403. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.005827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baramuli MA. Aspirasi DPR untuk Amandemen UU Kesehatan (Parliament Initiative to Amend the Health Law); 2004. Paper presented in the seminar ‘Recent Finding on Pregnancy Termination in Indonesia’, Jakarta, Indonesia, 11 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bedner A. Administrative Courts in Indonesia: A Socio-Legal Study. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Berry FS, Berry WD. Innovation and diffusion models in policy research. In: Sabatier PA, editor. Theories of the Policy Process. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 2007. pp. 223–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Social space and symbolic power. Sociological Theory. 1989;7:14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DL. Abortion, Islam, and the (1994) Cairo Population Conference. International Journal of Middle East Studies. 1997;29:161–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen JR. Islam, Law, and Equality in Indonesia: An Anthropology of Public Reasoning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brugha R, Varvasovsky Z. Stakeholder analysis: a review. Health Policy and Planning. 2000;15:239–46. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns P. The Leiden Legacy: Concepts of Law in Indonesia. Leiden, Netherlands: KITLV Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Buse K. Addressing the theoretical, practical and ethical challenges inherent in prospective health policy analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 2008;23:351–60. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse K, Walt G. Global public-private partnerships: part I – a new development in health? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:549–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Making Health Policy. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Candland C, Nurjanah S. Women’s Empowerment through Islamic Organisations: The Role of the Indonesia’s ‘Nahdlatul Ulama’ in Transforming the Government’s Birth Control Programme into a Family Welfare Programme. 2004. Online at: http://www.wellesley.edu/Polisci/Candland/KBIndonesia.pdf (accessed 27 October 2004)

- Dahl RA, Lindblom CE. Politics, Economics, and Welfare: Planning and Politico-Economic Systems Resolved into Basic Social Processes. New York: Harper & Row; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw E. Investigating policy networks for health: theory and method in a larger organisational perspective. WHO Regional Publications, European Series. 2001;92:185–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Jakarta: National Institute for Health Research and Development, Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia; 1995. Survei kesehatan rumah tangga (SKRT) 1995 (National Household Health Survey) [Google Scholar]

- Department of Laws and Human Rights. National Legislation Programme for 2005–09. 2008. Online at: http://www.djpp.depkumham.go.id/kerja/prolegnas.php?y=n&t=%282008%29&m=2 (accessed 10 May 2008)

- Dzuhayatin SR. Gender in contemporary Islamic studies. In: Pye M, Franke E, Wasim AT, Ma’sud A, editors. Religious Harmony Problems: Indonesia Practice and Education. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co.KG; 2006. pp. 161–7. [Google Scholar]

- Easton D. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. New York: Wiley; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Effendy B. Islamic militant movements in Indonesia: a preliminary account for its socio-religious and political aspects. Studia Islamika. 2004;11:393–428. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. The Constitution of Society; Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie P. Current issues in Indonesian Islam: analysing the 2005 Council of Indonesian Ulama Fatwa No.7 opposing pluralism, liberalism and secularism. Journal of Islamic Studies. 2007;18:202–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rosetti A, Bossert T. Enhancing the Political Feasibility of Health Reform: A Comparative Analysis of Chile, Colombia, Mexico. Boston MA: Data for Decision Making project; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hedayat KM. Therapeutic abortion in Islam: contemporary views of Muslim Shiite scholars and effect of recent Iranian legislation. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2006;32:652–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.015289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessini L. Global progress in abortion advocacy and policy: an assessment of the decade since ICPD. Reproductive Health Matters. 2005;13:88–100. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(05)25168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heywood A. Political Theory: An Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hull TH, Sarwono SW, Widyantoro N. Induced abortion in Indonesia. Studies in Family Planning. 1993;24:241–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein NJG. The voice of the ulama: fatwas and religious authority in Indonesia. Archives des sciences sociales des religions. 2004;125:115–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lukes S. Power: A Radical View. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lush L, Walt G, Ogden J. Transferring policies for treating sexually transmitted infections: what's wrong with global guidelines? Health Policy and Planning. 2003;18:18–30. doi: 10.1093/heapol/18.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire DC. Sacred Choice: the Right to Contraception and Abortion in Ten World Religions. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress Press; 2001. Contraception and abortion in Islam. [Google Scholar]

- Majchrzak A. Methods for Policy Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D. The development of the policy network approach. In: Marsh D, editor. Comparing Policy Networks. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1998. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Masyhuri A. Aborsi menurut Hukum Islam. In: Anshor MU, Wan Nedra Sururin, editors. Aborsi Dalam Fiqh Kontemporer. Jakarta: Balai Penerbit Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Indonesia; 2002. pp. 148–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia / World Health Organization. Indonesia Reproductive Health Profile 2003. Jakarta: Ministry of Health; 2003. p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Mintrom M. Policy entrepreneurs and the diffusion of innovation. American Journal of Political Science. 1997;41:738–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mydans S. With politics and market in mind, Megawati picks a cabinet. The New York Times. 2001. 10 August (2001). Online at: http://www.query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D06EFD8153FF933A2575BC0A9679C8B63 (accessed 12 March 2004)

- Oliver T. The politics of public health policy. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:195–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outka G, Brockopp JE. Islamic Ethics of Life: Abortion, War and Euthanasia. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- President of Indonesia. Presidential Speech. Opening speech on the inauguration of the new cabinet, 21 October (2004) 2004. Online at: http://www.presidenri.go.id/index.php/pidato/%282004%29/10/21/259.html, accessed 19 December 2007.

- Reich MR, Cooper DM. Brookline, MA: PoliMap; 1996. PolicyMaker: computer assisted political analysis. Software, version 2.3.1. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Indonesia. 1992 Law No. 23/1992 concerning Health, 17 September 1992, State Gazette Number 100 of 1992, Additional State Gazette Number 3495.

- Republic of Indonesia. 1998 Law No. 5/1998 concerning the ratification of the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 28 September 1998, State Gazette Number 164 of 1998.

- Republic of Indonesia. 2004a Law No. 29/2004 concerning Medical Practice, 6 October 2004, State Gazette Number 116 of 2004.

- Republic of Indonesia. 2004b Law No.30/2004 concerning Regulation to Bill/Law Making Process, 22 June 2004, State Gazette Number 53 of 2004.

- Republic of Indonesia. 2009 Law No.36/2009 concerning Health, 13 October 2009, State Gazette Number 144 of 2009, Additional State Gazette Number 5063.

- Republic of Indonesia. Undated. Kitab Undang-undang Hukum Pidana (Indonesian Criminal Code Book). Book II: Crimes, Chapter XIX: Crimes against Life. Articles 346–349. Official State Document.

- Roberts MJ, Hsiao W, Berman P, Reich MR. Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Performance and Equity. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier PA. The Need for Better Theories. In: Sabatier PA, editor. Theories of the Policy Process. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1999. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schenker JG. Women’s reproductive health: monotheistic religious perspectives. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2000;70:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H. On the fault-line: the politics of AIDS policy in contemporary South Africa. African Studies. 2002;61:145–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sciortino R, Natsier LM, Mas’udi MF. Learning from Islam: advocacy of reproductive rights in Indonesian pesantren. Reproductive Health Matters. 1996;8:86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Shretta R, Walt G, Brugha R, Snow RW. A political analysis of corporate drug donations: the example of Malarone in Kenya. Health Policy and Planning. 2001;16:161–70. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank D. Global Capital, Political Institutions and Policy Change in Developed Welfare States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Trostle A, Bronfman M, Langer A. How do researchers influence decision makers? Case studies from Mexico. Health Policy and Planning. 1999;14:103–14. doi: 10.1093/heapol/14.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2007/2008. 2007. Country profile: Indonesia. Online at: http://www.hdrstats.undp.org/countries/data_sheets/cty_ds_IDN.html (accessed 20 May 2008)

- Utomo B, Jatiputra S, Tjokronegoro A. Abortion in Indonesia: A Review of the Literature. Jakarta: Faculty of Public Health, University of Indonesia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Varvasovsky Z, Brugha R. How to do (or not to do)… A stakeholder analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 2000;15:338–45. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt G. Health Policy: An Introduction to Process and Power. London: Zed books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Walt G, Gilson L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 1994;9:353–70. doi: 10.1093/heapol/9.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walt G, Lush L, Ogden J. International organizations in transfer of infectious diseases: iterative loops of adoption, adaptation, and marketing. Governance. 2004;17:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Zenzie CU. Indonesia’s new political spectrum. Asian Survey. 1999;39:243–64. [Google Scholar]