Abstract

Aims

To characterize geographic differences in clinical characteristics and care of patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HF-PEF).

Methods and results

Using data on 61 182 admissions in 307 US hospitals from March 2004 to March 2006 from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE)-United States (US) database and 10 904 admissions in 70 hospitals from 10 countries from March 2005 to January 2009 from the ADHERE-International (I) database composed of countries in Asia-Pacific and Latin-American regions, we compared characteristics, treatments, length of stay, and in-hospital mortality between patients with PEF (left ventricular EF ≥ 40%). There were 26 258 (49.6%) admissions with HF-PEF in the ADHERE-US and 4206 (45.7%) in ADHERE-I. The USA cohort was older [median 77.2 years (25th, 75th, 66.5, and 84.4) vs. 71.0 (59.0, 79.0), P< 0.001] and more likely to be female (61.8 vs. 54.7%, P< 0.001). The international cohort had a longer length of stay [median 6.0 days (4.0, 10.0)] vs. 4.0 days [3.0, 7.0], P< 0.001) and higher use of inotropes (12.5 vs. 4.8%, P< 0.001). At discharge, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers, and diuretics were prescribed more in the USA (57.6 vs. 54.4%, P< 0.001; 63.0 vs. 35.5%, P< 0.001; 78.2 vs. 76.2%, P< 0.001); digoxin was prescribed more outside the USA (26.0 vs. 17.7%, P< 0.001). After adjusting for baseline characteristics, 7-day inpatient mortality was similar between the international and the USA cohorts [hazard ratio 0.80, 95% CI (0.61–1.05); P= 0.11].

Conclusions

Clinical characteristics, inpatient interventions, discharge therapies, and length of stay vary significantly for HF-PEF patients across geographic regions. This has important implications for global clinical trials and outcome studies in HF.

Keywords: heart failure, preserved ejection fraction, registries

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (PEF) is common.1,2 Recent cross-sectional studies of ambulatory patients in the USA and Europe estimated the prevalence of HF-PEF to range from 40 to 71% (mean 56%), depending on the definition applied.3–5 In-hospital cohort studies in the USA, Europe, and Japan have found the prevalence to range from 24 to 55% (mean 41%) with some studies indicating that the prevalence is increasing.6–9

While much attention has focused on patients with HF with reduced EF, HF-PEF has several unique clinical characteristics.1,2,10–13 Patients with HF-PEF are more likely to be older and female and have a lower HF class designation.14,15 In contrast to patients with HF and reduced EF, patients with HF-PEF are less likely to have severe dyspnoea and less likely to have a good prognosis despite similar therapy.16–18 Prior studies have shown that the treatment of patients with HF-PEF is often different when compared with patients with reduced EF, in part, due to the lack of a clear evidence base for therapies.19–23 Thus, the European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines do not have any class I recommendations for medical therapy beyond management of pre-existing conditions for HFPEF.24,25 However, some may consider the use of ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and beta-blockers based on modest benefit in prior studies.20,23–26 Regardless of these differences, several studies show that patients with HF-PEF have high mortality and hospitalization rates.10,12,13

Despite HF being a global epidemic, the vast majority of studies for HF-PEF have taken place in the USA or Europe. Little is known about the clinical differences between HF-PEF patients in Asia-Pacific and Latin America and the USA. Contemporary approaches to inpatient and discharge treatment as well as inpatient outcomes are unknown. Therefore, we sought to characterize differences between patients hospitalized with HF-PEF enrolled in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE)-United States (US) registry vs. those in the ADHERE-International (I) registry enrolled from Asian-Pacific and Latin-American regions.

Methods

Data sources

Our retrospective analysis examining the differences between patients began with the use of two databases on hospital admissions for patients with HF. The ADHERE-US registry collected data on 61 182 admissions from 307 hospitals from March 2004 to March 2006. The ADHERE-I registry collected data on 10 904 admissions from 70 hospitals in 10 countries (Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, Australia, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Brazil, and Mexico) from March 2005 to January 2009.

Details of the objectives, design, and methods in ADHERE-US have been previously described.13 ADHERE hospitals, community, tertiary, and academic centres, were located throughout the USA and are demographically representative of nation as a whole.13 The registry collected information on demographic features, medical history, clinical characteristics, initial evaluations, therapeutic management, and in-hospital outcomes. Data were collected from medical records by trained abstractors at each participating site and were recorded with the use of an electronic case report form. Importantly, registry participation did not require any alteration of treatment or hospital care, and entry of data into the registry was not contingent on the use of any particular therapeutic agent or treatment regimen.

The ADHERE-I registry used a design similar to the ADHERE-US registry. Approximately 70 hospitals, ranging in size from 130 to 2 908 beds (mean = 812) participated in registry of adult inpatients (≥18 years of age) with a principal diagnosis of acute decompensated HF (identified by ICD-9/10 code). Patient medical records were reviewed by trained research personnel at every hospital to collect data on demographics, past medical history symptoms and signs upon presentation at the hospital, diagnostic procedures, inpatient treatments, in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and discharge medications including contraindications for therapies used as quality measures. Approval for the study by the local institutional human research ethics committee was obtained at each site.

Study population

Eligible patients had to be ≥18 years of age and hospitalized primarily for HF. Preserved ejection fraction was defined as a left ventricular (LV) EF ≥ 40%. Patients with missing EFs were excluded.

Outcomes

The outcomes examined included length of stay (calculated in days from admission to discharge) and all-cause in-hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and clinical outcomes such as length of stay and in-hospital mortality were compared between the USA and International HF-PEF cohorts. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous variables; Pearson's χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Percentages and medians (25th and 75th percentiles) were used to describe the distribution of categorical and continuous variables.

Multivariable regression models were performed to examine the association of patient characteristics and region with length of hospital stay. The generalized estimating equations approach was employed to adjust for within-hospital clustering. Because of a small proportion of patients with long hospital stays, length of stay was first log transformed to correct for its right-skewed distribution. Due to the log transformation in the model, the estimated parameters represent multiplicative effects (i.e. the degree to which a risk factor increases or decreases length of stay compared with those patients without the risk factor present). Thus, the ratio of length of stay among patients enrolled in ADHERE-I regions to those enrolled in the USA was reported. For this analysis, patients transferred to another hospital were excluded.

A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate the patient characteristics and region associated with all-cause mortality within 7 days of admission. As hospital length of stay varied, the Cox proportional hazard model was applied since it analyzes morality events per each hospital day at risk. In addition to region, the variables in the model included demographics; medical history; clinical characteristics and vital signs at admission; and laboratory values. The rates of missing in the data are low (<6%). A simple imputation was used to handle missing data in the model, that is, missing of categorical variables was imputed to dominant category, and missing of continuous variables was imputed to median value.

All P values are two-sided; P< 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

In ADHERE-US, 52 926 (86.5%) of 61 182 admissions had LV function measured. Of these, we identified 26 258 (49.6%) with HF and PEF. In ADHERE-I, 9208 (84.5%) of 10 904 admissions had LV function measured. Of these, we identified 4206 (45.7%) with HF and PEF.

The median age among the ADHERE-US cohort with HF and PEF was 77.2 (25th, 75th, 66.5, and 84.4) years and overall 61.8% were female; median age of the ADHERE-I cohort was 71.0 (59.0 and 79.0) years and 54.7% were female (Table 1). The US cohort had a greater percentage of patients with a history of atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease/ischaemic heart disease, prior myocardial infarction, prior cerebrovascular accident/transient ischaemic attack, pulmonary disease, renal insufficiency (higher dialysis use), anaemia, and current smoking (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| ADHERE-US | ADHERE-International | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 26 258) | (n= 4206) | ||

| Age, median (25th, 75th), years | 77.2 (66.5, 84.4) | 71.0 (59.0, 79.0) | <0.001 |

| Female, % | 61.8 | 54.7 | <0.001 |

| Medical history, % | |||

| CAD/IHD | 54.1 | 42.4 | <0.001 |

| Prior MI | 22.8 | 21.2 | 0.021 |

| Renal insufficiency | 30.2 | 21.5 | <0.001 |

| Dialysis | 5.5 | 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 33.9 | 30.8 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 47.3 | 44.2 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 81.3 | 67.8 | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 41.0 | 39.7 | 0.114 |

| Prior CVA/TIA | 17.6 | 13.4 | <0.001 |

| PVD | 17.9 | 5.6 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary disease | 33.4 | 14.1 | <0.001 |

| Anaemia | 60.5 | 57.0 | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 11.2 | 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Clinical presentation characteristics at admission, % | |||

| Dyspnoea | 90.2 | 94.9 | <0.001 |

| Dyspnoea at rest | 32.9 | 40.6 | <0.001 |

| Fatigue | 28.6 | 46.4 | <0.001 |

| Rales | 65.6 | 80.0 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral oedema | 68.0 | 62.3 | <0.001 |

| Vital signs, median (25th, 75th) | |||

| Pulse at admission, bpm | 82.0 (72.0, 97.0) | 88.0 (74.0, 105.0) | <0.001 |

| RR at admission, breath/minute | 21.0 (20.0, 24.0) | 22.0 (19.0, 26.0) | <0.001 |

| SBP at admission, mmHg | 148.0 (127.0, 171.0) | 140.0 (120.0, 161.0) | <0.001 |

| Weight change from admission to discharge, kg | −2.3 (−4.6, −0.3) | −1.6 (−4.0, 0.0) | <0.001 |

| Initial ECG characteristics, % | |||

| NSR | 46.9 | 49.6 | <0.001 |

| Paced rhythm | 9.6 | 2.6 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 22.4 | 29.4 | <0.001 |

| Bradycardia | 4.5 | 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Admission laboratory data | |||

| Sodium, median (25th, 75th), mmol/L | 139.0 (136.0, 141.0) | 138.0 (135.0, 141.0) | <0.001 |

| Potassium, median (25th, 75th), mmol/L | 4.2 (3.8, 4.7) | 4.1 (3.7, 4.5) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, median (25th, 75th), mg/dL | 1.3 (1.0, 1.9) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.8) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin, median (25th, 75th), g/dL | 11.7 (10.4, 13.1) | 11.9 (10.4, 13.4) | <0.001 |

| Pro-BNP, median (25th, 75th), pg/mL | 3087.0 (1179.0, 7674.0) | 2779.0 (1078.0, 6928.0) | 0.140 |

| Troponin positive, % | 4.7 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; bpm, beats per minute; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; ECG, electrocardiogram; HF-PEF, heart failure-preserved ejection fraction; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction; NSR, normal sinus rhythm; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; RR, respiratory rate; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Upon presentation, the US cohort had decreased reports of dyspnoea, dyspnoea at rest, fatigue, and rales but more cases of peripheral oedema (Table 1). Additionally, more patients had paced rhythm and bradycardia, and there were fewer cases of atrial fibrillation or flutter (Table 1). Also, over the course of hospitalization there was more reported total and per hospital day weight loss in the US cohort (median −2.3 kg [25th, 75th, −4.6, −0.3] vs. −1.6 kg [−4.0, 0.0]; P< 0.001) (Table 1). In the US cohort, there was increased pre-hospital use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/ARBs, beta-blockers, warfarin, lipid-lowering agents, clopidogrel, aspirin, and diuretics (loop diuretics or aldosterone antagonists), but lower use of nitrates and digoxin (Table 2).

Table 2.

Admission medications, inpatient treatment, and discharge medicationsa

| ADHERE-US | ADHERE-International | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 26 258) | (n= 4206) | ||

| Admission medications, % | |||

| ACE Inhibitor | 36.0 | 32.3 | <0.001 |

| ARB | 15.8 | 14.4 | 0.017 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 49.8 | 44.8 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 57.8 | 36.0 | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 24.2 | 15.4 | <0.001 |

| Loop Diuretic | 62.4 | 54.3 | <0.001 |

| Aldosterone Antagonist | 7.4 | 14.1 | <0.001 |

| Diuretic (loop/aldosterone antagonist) | 66.7 | 56.4 | <0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering agent | 39.6 | 36.5 | <0.001 |

| Digoxin | 16.8 | 23.7 | <0.001 |

| Nitrates | 22.8 | 30.0 | <0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 13.8 | 11.6 | <0.001 |

| Aspirin | 40.7 | 38.9 | 0.026 |

| Therapeutic interventions | |||

| Any inotrope, % | 4.8 | 12.5 | <0.001 |

| Any vasodilator, % | 21.4 | 15.9 | <0.001 |

| Defibrillation, % | 0.6 | 1.5 | <0.001 |

| CPR, % | 0.8 | 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation, % | 3.2 | 9.7 | <0.001 |

| Duration of ICU/CCU, median (25th, 75th), days | 2.3 (1.3, 4.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 7.0) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac catheterization, % | 7.7 | 10.5 | <0.001 |

| Discharge medications, % | |||

| ACE Inhibitor | 43.4 | 41.3 | 0.009 |

| ARB | 16.0 | 15.0 | 0.075 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 57.6 | 54.4 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 63.0 | 35.5 | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 25.4 | 18.5 | <0.001 |

| Loop Diuretic | 75.7 | 74.2 | <0.001 |

| Aldosterone Antagonist | 11.7 | 21.5 | <0.001 |

| Diuretic (loop/aldosterone antagonist) | 78.2 | 76.2 | 0.002 |

| Lipid-lowering agent | 40.6 | 41.4 | <0.001 |

| Digoxin | 17.7 | 26.0 | <0.001 |

| Nitrates | 26.1 | 36.6 | <0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 15.2 | 14.2 | 0.104 |

| Aspirin | 46.5 | 44.3 | 0.007 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCU, cardiac care unit; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; HF-PEF, heart failure-preserved ejection fraction; ICU, intensive care unit.

aThese values reflect all individuals who received the specified therapies.

Examining inpatient treatment, the ADHERE-I cohort had a higher use of intravenous inotropic agents (12.5%) compared with the US cohort (4.8%), but a lower use of intravenous vasodilators (15.9 vs. 21.4%) (Table 2). Additionally, the ADHERE-I cohort had a greater use of interventions like cardiopulmonary resuscitation, defibrillation, mechanical ventilation, cardiac catheterization, and longer stays in the intensive care unit. Use of inotropic agents, vasodilators, mechanical ventilation, and cardiac catheterization differed by country (Table 3).

Table 3.

Observed inpatient mortality, treatments, and procedures by countrya

| Country | Inpatient Mortality Rate (%) | Inotropic Agent (%) | Vasodilator (%) | Mechanical Ventilation (%) | Cardiac Catheterization (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil (n= 151) | 8.5 | 16.4 | 18.8 | 14.6 | 10.3 |

| Philippines (n= 232) | 6.1 | 25.9 | 14.9 | 8.9 | 6.9 |

| Australia (n= 340) | 5.3 | 3.4 | 11.7 | 10.6 | 15.9 |

| Indonesia (n= 477) | 4.9 | 10.8 | 22.1 | 9.8 | 2.8 |

| Taiwan (n= 258) | 4.8 | 25.8 | 33.2 | 15.5 | 15.8 |

| Thailand (n= 989) | 4.6 | 21.8 | 20.4 | 18.5 | 19.1 |

| Malaysia (n= 218) | 4.0 | 9.3 | 17.2 | 4.9 | 6.6 |

| Mexico (n= 33) | 2.9 | 17.6 | 38.2 | 11.8 | 8.8 |

| US (n= 25,064) | 2.7 | 4.7 | 21.2 | 7.7 | 3.2 |

| Singapore (n= 1029) | 2.2 | 1.5 | 6.4 | 2.8 | 2.0 |

| Hong Kong (n= 183) | 0.5 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 9.2 | 4.9 |

aValues are presented as percentages. Mortality rates are observed rates without censuring at 7 days.

Upon discharge, the US cohort had a higher prevalence of prescriptions for ACE inhibitors/ARBs, warfarin, beta-blockers, diuretics, clopidogrel and aspirin, but lipid-lowering agents, nitrates, and digoxin were more often prescribed for the ADHERE-I cohort (Table 2).

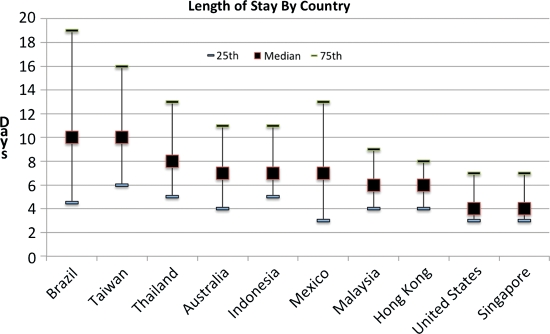

The ADHERE-I cohort had a longer median length of stay (6.0 days [4.0, 10.0]) as compared with the US cohort (4.0 days [3.0, 7.0]). After adjusting for patient characteristics, it was demonstrated that ADHERE-I cohort had a longer length of stay [adjusted ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.45–1.76; P< 0.001]. In general, Latin-American countries had a longer average length of stay when compared with Asian-Pacific countries and the USA (Figure 1). In-hospital mortality rates (unadjusted) for patients hospitalized with HF and PEF showed wide variation by the country of enrollment (Table 3). The USA had the third-lowest observed inpatient mortality rate, Brazil had the highest, and Hong Kong had the lowest. After adjusting for baseline patient characteristics and considering hospital days at risk, there was no difference in the risk of death for the ADHERE-I cohort compared with the US cohort. (hazard ratio 0.8, 95% CI 0.6–1.0; P= 0.11) (Table 4). Age, dyspnoea at rest, diagnosis of HF, fatigue, heart rate, rales, and blood urea nitrogen were associated with an increased hazard of inpatient death, while dyslipidaemia, increasing systolic blood pressure, and increasing sodium levels were associated with a lower hazard of inpatient death (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Length of stay by country. Reported values are medians with 25th and 75th interquartile ranges.

Table 4.

Cox model for all-cause in-hospital mortality

| Multivariable Modela HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| AP-LA vs. USb | 0.86 (0.61, 1.20) | 0.367 |

| AP-LA vs. USc | 0.80 (0.61, 1.05) | 0.112 |

| Age, per 1 year increase | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.70 (0.58, 0.85) | <0.001 |

| HF Dyspnoea at rest | 1.71 (1.41, 2.08) | <0.001 |

| Fatigue | 1.31 (1.08, 1.59) | 0.006 |

| Rales Heart rate, per 10 unit increase | 1.10 (1.07, 1.14) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP, per 10 unit increase | 0.82 (0.79, 0.85) | <0.001 |

| Sodium, per 1 unit increase | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | <0.001 |

| BUN, per 10 unit increase | 1.13 (1.09, 1.17) | <0.001 |

BP, blood pressure; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; AP-LA, Asian-Pacific Latin American.

aC = 0.705, multivariable analysis adjusted for patient risk factors, including age, gender, medical history of atrial fibrillation, pulmonary, diabetes, PVD, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, stroke, anaemia, CAD, MI, HF, renal insufficiency, dialysis, and smoker, congestion at first X-ray, dyspnoea, dyspnoea at rest, fatigue, oedema, rales, vital signs − heart rate, systolic BP, lab data sodium, creatinine, haemoglobin, and BUN.

bUnadjusted for patient risk factors.

cAdjusted for patient risk factors; patient risk factors not contributing to increase in in-hospital mortality: female, atrial fibrillation, COPD, HTN, diabetes mellitus, PVD, CAD, stroke, MI, anemia, HF, renal insufficiency, dialysis, smoker, congestion at first X-ray, dyspnoea, rales, oedema, and creatinine.

Discussion

This is among the largest studies evaluating international differences in HF-PEF. Overall, this study demonstrates that significant differences in HF-PEF patient characteristics are present between hospitalizations based on geographic regions. Pre-hospitalization, inpatient, and discharge treatments differ significantly by region. There are also marked variations in hospital length of stay across countries. Heart failure with PEF patients in ADHERE-I hospitals had less net weight loss during hospitalization than in the USA, despite longer length of stay. Finally, after adjustment for baseline characteristics, the risk of inpatient mortality for HF and PEF is not lower outside the USA.

Similar to prior studies, patient characteristics and clinical signs on admission were different in the USA compared with other regions.13,16,18 Patients in the US cohort were older and more likely female and were more likely to present with comorbidities (e.g. prior myocardial infarction, renal insufficiency, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc.) and peripheral oedema compared with patients outside the USA.16 Overall, these differences in patients admitted to hospitals in the USA suggest a higher risk cohort compared with admissions in other areas of the world. This may be due to HF-PEF patients having more care in the ambulatory setting in the USA or other systematic differences in care compared with other countries.

The differences in managing HF-PEF underscore, in part, the lack of a consensus in the inpatient and outpatient treatment of HF-PEF.2 We observed that patients were admitted and discharged with therapy regimens that significantly differed based on the region of the world. In terms of inpatient treatment, patients in ADHERE-I were much more likely to receive inotropic agents, although there is little evidence to guide the use of inotropes in patients with HF-PEF and observational studies indicate a higher mortality risk.21,27 This is in contrast to previous work that demonstrated a higher use of inotropes in HF-PEF patients in North America compared with other regions such as Europe.16 In addition, other procedures such as cardiac catheterization were also more common in ADHERE-I. At discharge, US patients were more likely to be prescribed ACE inhibitors/ARBs and beta-blockers than ADHERE-I patients who were more likely to be prescribed diuretics. Previously, North American patients were found to use ACE inhibitors/ARBs and diuretics less often at discharge than an international cohort, while beta-blockers were used more often.16

The observed differences in length of stay can be attributed to the types of health care systems or incentives for care as well as differences in physician practice patterns. The health care systems in the USA and other parts of the world differ in structure, administration, funding, accessibility, and delivery of care.28,29 Because of different incentives, length of stay may differ due to reimbursement or location of services. Interestingly, in the USA, patient characteristics generally highlight a sicker population yet the length of stay is much shorter than in other parts of the world. Examining care in other parts of the world may assist policymakers considering changes to the current US model of health care with its incentives for short length of stay.

The investigation of inpatient mortality did not reveal a significant difference between the USA and other regions of the world, even after adjustment for baseline characteristics and length of stay. Previous studies have revealed regional differences in mortality in HF patients.13,16 One study found that South America had the highest mortality rate followed by Western Europe, and the USA; Eastern Europe had the fewest deaths.16 ADHERE-I patients did not have a statistically significant difference in the risk of in-hospital mortality as compared with ADHERE-US patients. In general, patients hospitalized in ADHERE-I with HF-PEF are younger with less comorbidities than the ADHERE-US cohort, yet nevertheless face an equal hazard of inpatient death. Residual confounding may be present in evaluating the lack of differences in regional outcomes.

Our study also has important implications for the future research of patients with HF-PEF. With the escalating costs of conducting clinical research, there is a growing interest in conducting clinical trials in many areas around the world. However, as we have demonstrated in this study, patient characteristics, treatments, health care systems, and perhaps outcomes, differ regionally and the results of research confined to one region may not be easily generalized.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted for this analysis. First, there are temporal differences by a few years in the study period between the ADHERE-US and ADHERE-I registry cohorts. However, the differences observed are not likely to be significantly influenced by modest time frame secular trends. Second, ADHERE-US was a quality improvement project with voluntary participation; meaning it may not reflect general practice, although prior studies have suggested these patients appeared to be representative of US HF patients.30 Third, ADHERE-I represents select sites from select countries and may not be fully representative of the Asia-Pacific or Latin-American regions. Fourth, known or unknown residual confounding factors may influence the results of the models used in this observational study. Finally, outcomes are limited to the hospital stay and information on patient-reported outcomes is unavailable.

Conclusions

Our analysis from the ADHERE-US and ADHERE-I databases show significant regional differences in patient demographics, therapies, and length of stay, yet similar in-hospital mortality in patients with HF-PEF. The variation in care and the lack of evidence-based therapies illustrates the major challenges for inpatient and outpatient treatment of patients with HF-PEF. These findings have important implications for global clinical trials and outcomes studies in HF.

Funding

This research was supported in part by Duke University's CTSA grant TL1 RR024126 from NCRR/NIH. ADHERE was sponsored by Scios Inc. and ADHERE-International was sponsored by Janssen-Cilag Asia Pacific.

Conflict of interest: A.F.H. reported research funding from Johnson & Johnson (significant), Amylin (significant) and honorarium from AstraZeneca (modest), Corthera (modest), and Amgen (modest).

G.C.F. reports research funding from the NHLBI (significant), consulting for Novartis (significant), Johnson & Johnson (modest), and honorarium Medtronic (modest).

R.M.M. is an employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs and reported receiving stock in Johnson & Johnson as part of his employment.

C.M.O. reported research funding from Johnson & Johnson.

References

- 1.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paulus WJ, van Ballegoij JJ. Treatment of heart failure with normal ejection fraction: an inconvenient truth. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:526–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowie MR, Wood DA, Coats AJ, Thompson SG, Poole-Wilson PA, Suresh V, Sutton GC. Incidence and aetiology of heart failure; a population-based study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:421–428. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieminen MS, Brutsaert D, Dickstein K, Drexler H, Follath F, Harjola VP, Hochadel M, Komajda M, Lassus J, Lopez-Sendon JL, Ponikowski P, Tavazzi L EuroHeart Survey Investigators, Heart Failure Association, European Society of Cardiology. EuroHeart Failure Survey II (EHFS II): a survey on hospitalized acute heart failure patients: description of population. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2725–2736. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, Jr, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. JAMA. 2003;289:194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goda A, Yamashita T, Suzuki S, Ohtsuka T, Uejima T, Oikawa Y, Yajima J, Koike A, Nagashima K, Kirigaya H, Sagara K, Ogasawara K, Isobe M, Sawada H, Aizawa T. Prevalence and prognosis of patients with heart failure in Tokyo: a prospective cohort of Shinken Database 2004–5. Int Heart J. 2009;50:609–625. doi: 10.1536/ihj.50.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafsson F, Torp-Pedersen C, Brendorp B, Seibaek M, Burchardt H, Køber L DIAMOND Study Group. Long-term survival in patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure: relation to preserved and reduced left ventricular systolic function. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:863–870. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00845-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Hamaguchi S, Kinugawa S, Yokota T, Goto D, Yokoshiki H, Kato N, Takeshita A, Tsutsui H JCARE-CARD Investigators. Characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients with heart failure and reduced vs preserved ejection fraction. Report from the Japanese Cardiac Registry of Heart Failure in Cardiology (JCARE-CARD) Circ J. 2009;73:1893–1900. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, Takeshita A. Mortality and readmission of hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure and preserved versus depressed systolic function. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:530–533. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01732-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Sun JL, Yancy CW, Young JB OPTIMIZE-HF Investigators and Hospitals. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogg K, Swedberg K, McMurray J. Heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function; epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tribouilloy C, Rusinaru D, Mahjoub H, Soulière V, Lévy F, Peltier M, Slama M, Massy Z. Prognosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a 5 year prospective population-based study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:339–347. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW, De Marco T, Fonarow GC ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam CS, Donal E, Kraigher-Krainer E, Vasan RS. Epidemiology and clinical course of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:18–28. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Kinugawa S. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: lessons from epidemiological studies. J Cardiol. 2010;55:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blair JE, Zannad F, Konstam MA, Cook T, Traver B, Burnett JC, Jr, Grinfeld L, Krasa H, Maggioni AP, Orlandi C, Swedberg K, Udelson JE, Zimmer C, Gheorghiade M EVEREST Investigators. Continental differences in clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with worsening heart failure results from the EVEREST (Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure: Outcome Study with Tolvaptan) program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1640–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleland JG, Tendera M, Adamus J, Freemantle N, Polonski L, Taylor J. The Perindopril in Elderly People with Chronic Heart Failure (PEP-CHF) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2338–2345. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMurray JJ, Carson PE, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Zile MR, Ptaszynska A, Staiger C, Donovan JM, Massie BM. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: clinical characteristics of 4133 patients enrolled in the I-PRESERVE trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, Zile MR, Young JB, Kitzman DW, Love TE, Aronow WS, Adams KF, Jr, Gheorghiade M. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114:397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holland C, Kumbhani DJ, Ahmed SH, Marwick TH. Effects of treatment on exercise tolerance, cardiac function, and mortality in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1676–1686. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abraham WT, Adams KF, Fonarow GC, Costanzo MR, Berkowitz RL, LeJemtel TH, Cheng ML, Wynne J ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators; ADHERE Study Group. In-hospital mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure requiring intravenous vasoactive medications: an analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mebazaa A, Nieminen MS, Packer M, Cohen-Solal A, Kleber FX, Pocock SJ, Thakkar R, Padley RJ, Põder P, Kivikko M SURVIVE Investigators. Levosimendan vs dobutamine for patients with acute decompensated heart failure: the SURVIVE Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1883–1891. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.17.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003;362:777–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW. 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:1977–2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, McMurray JJ, Ponikowski P, Poole-Wilson PA, Strömberg A, van Veldhuisen DJ, Atar D, Hoes AW, Keren A, Mebazaa A, Nieminen M, Priori SG, Swedberg K ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:933–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.v van Veldhuisen DJ, Cohen-Solal A, Böhm M, Anker SD, Babalis D, Roughton M, Coats AJ, Poole-Wilson PA, Flather MD SENIORS Investigators. Beta-blockade with nebivolol in elderly heart failure patients with impaired and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: Data From SENIORS (Study of Effects of Nebivolol Intervention on Outcomes and Rehospitalization in Seniors With Heart Failure) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2150–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felker GM, O'Connor CM. Inotropic therapy for heart failure: an evidence-based approach. Am Heart J. 2001;142:393–401. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.117606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desai M, Rachet B, Coleman MP, McKee M. Two countries divided by a common language: health systems in the UK and USA. J R Soc Med. 2010;103:283–287. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2010.100126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mays GP, Smith SA, Ingram RC, Racster LJ, Lamberth CD, Lovely ES. Public health delivery systems: evidence, uncertainty, and emerging research needs. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heidenreich PA, Fonarow GC. Are registry hospitals different? A comparison of patients admitted to hospitals of a commercial heart failure registry with those from national and community cohorts. Am Heart J. 2006;152:935–939. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]