Abstract

Purpose

Colorectal cancer (CRC) develops as a result of a series of accumulated genomic changes that produce oncogene activation and tumor suppressor gene loss. These characteristics may classify CRC into subsets of distinct clinical behaviors.

Patients and Methods

We studied two of these genomic defects—mismatch repair deficiency (MMR-D) and loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q (18qLOH)—in patients enrolled onto two phase III cooperative group trials for treatment of potentially curable colon cancer. These trials included prospective secondary analyses to determine the relationship between these markers and treatment outcome. A total of 1,852 patients were tested for MMR status and 955 (excluding patients with MMR-D tumors) for 18qLOH.

Results

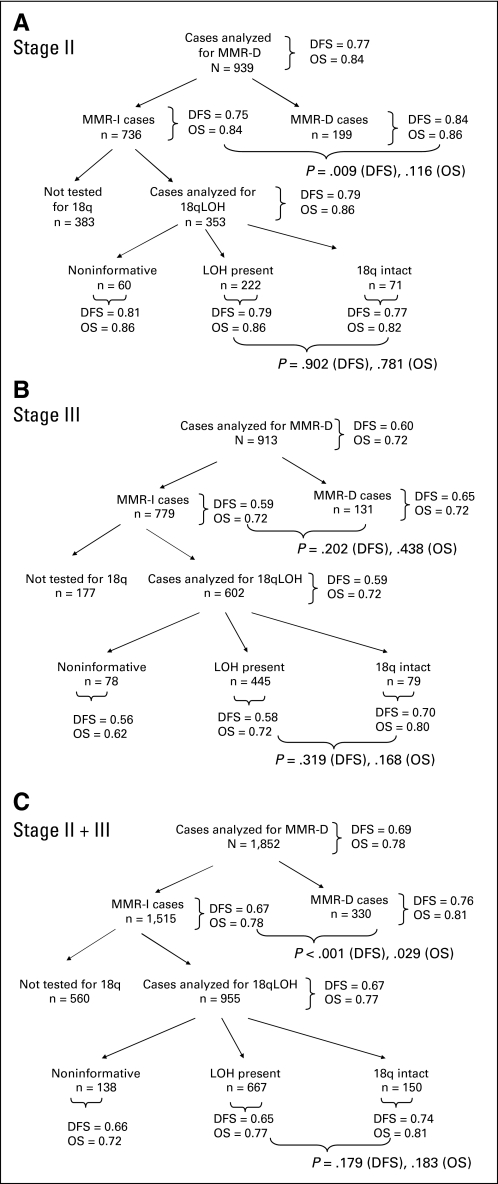

Compared with stage III, more stage II tumors were MMR-D (21.3% v 14.4%; P < .001) and were intact at 18q (24.2% v 15.1%; P = .001). For the combined cohort, patients with MMR-D tumors had better 5-year disease-free survival (DFS; 0.76 v 0.67; P < .001) and overall survival (OS; 0.81 v 0.78; P = .029) than those with MMR intact (MMR-I) tumors. Among patients with MMR-I tumors, the status of 18q did not affect outcome, with 5-year values for patients with 18q intact versus 18qLOH tumors of 0.74 versus 0.65 (P = .18) for DFS and 0.81 versus 0.77 (P = .18) for OS.

Conclusion

We conclude that MMR-D tumor status, but not the presence of 18qLOH, has prognostic value for stages II and III colon cancer.

INTRODUCTION

In potentially curable colorectal cancer (CRC), current staging methods do not optimally distinguish between patients cured by surgery alone and those at high risk of disease recurrence after surgery. When classified using current clinicopathologic staging, roughly 20% of patients with stage II colon cancer will develop postsurgical disease recurrence, and it is not possible to identify a high-risk subset of patients with stage II disease who might benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. For patients with stage III CRC, adjuvant chemotherapy has an established role; however, a significant percentage of patients receive chemotherapy without benefit. These patients include approximately one third of stage III patients whose disease is cured after surgery alone and another 25% whose disease recurs despite adjuvant treatment. It is clear from these observations that both patient care and health care resource utilization would be dramatically improved by developing tumor-specific markers that identify high- and low-risk CRC subsets.

CRCs accumulate specific genetic changes as they develop from benign lesions to invasive tumors, and the nature of these changes can divide CRCs into distinct subsets.1 This study reports a prospective analysis of two genetic defects as predictors of outcome for patients with stages II and III colon cancer. The first marker involves an acquired defect that produces an inability to repair single-nucleotide DNA mismatches, a condition known as mismatch repair deficiency (MMR-D). Sporadic CRCs commonly acquire MMR-D by methylation-associated silencing of MLH-1, a gene encoding a key mismatch repair protein. Tumors with MMR-D can be identified by frequent alterations in di- and trinucleotide repeat sequences known as microsatellites, a condition termed microsatellite instability high (MSI-H). A substantial body of data indicates that patients with CRC whose tumors demonstrate MMR-D (or MSI-H) have less aggressive disease. Studies from randomized clinical trials have associated MMR-D status with better prognosis after treatment of stages II and III disease and suggested that these patients do not benefit from treatment with fluorouracil (FU) -based adjuvant chemotherapy.2–8

Chromosomal instability (CIN), a condition of faulty segregation of sister chromatids during mitosis, is another genomic alteration commonly observed in CRC. As a result of CIN, CRCs exhibit losses at multiple tumor suppressor loci, particularly those located on 5q, 8p, 17p, and 18q. This process is distinct from MMR-D (ie, CRCs that demonstrate CIN do not have MMR-D, and vice versa). Early studies showed that patients whose tumors lacked regions on 18q as a result of CIN experienced poor overall survival (OS) when compared with patients whose tumors maintained intact 18q alleles.4,9 The most common method used to detect 18q loss relies on assays that examine two distinct alleles at a particular chromosomal location, a condition known as heterozygosity. A normal tissue specimen is compared with a tumor sample from the same patient, and DNA loss is identified if one of the alleles present in the normal specimen is lost in the tumor, a condition termed loss of heterozygosity (LOH). Although multiple studies have examined the relationship between 18qLOH and treatment outcome in patients with CRC, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the current literature because of conflicting data and lack of comparability between studies.

Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) conducted separate randomized trials of adjuvant therapy in patients with stages II (CALGB protocol 9581) and III (CALGB protocol 89803) CRCs. Each of these trials also included prospective determination of the relationship between tumor MMR and 18q status and treatment outcome as secondary study end points.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

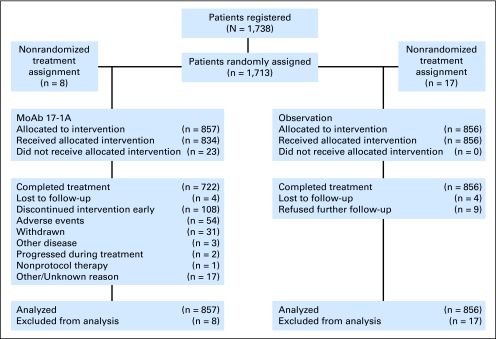

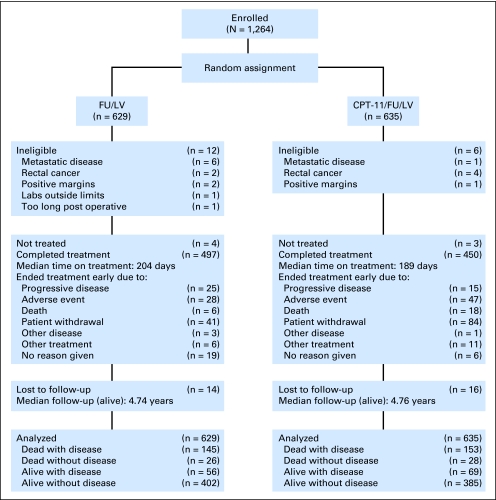

After tumor resection, patients with stage II CRC (n = 1,738) were randomly assigned to either receive edrecolomab or undergo observation (CALGB 9581), and patients with stage III CRC (n = 1,264) were randomly assigned to receive either FU plus leucovorin (FU/LV) or FU, leucovorin, and irinotecan (IFL; CALGB 89803; Figs 1, 2).10 The primary end point for both trials was OS; disease-free survival (DFS) was a secondary end point. Secondary aims addressed the relationship between tumor-associated risk factors and treatment outcome. These protocols were reviewed by the institutional review board of each center; all patients provided written informed consent.

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram, Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9581.

Fig 2.

CONSORT diagram, Cancer and Leukemia Group B 89803. CPT-11, irinotecan; FU, fluorouracil; LV, leucovorin.

The CALGB Statistical Center (Durham, NC) maintained the research database. Eligible patients were assigned by randomized fixed block to either undergo observation or receive edrecolomab (CALGB 9581) or IFL or FU/LV (CALGB 89803). Treatment description and results of CALGB 9581 are provided in Journal of Clinical Oncology by Niedzwiecki et al11; they have been published previously for CALGB 89803.10

Detection of MSI and MMR-D

For each patient case, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded primary tumor and normal colon underwent histology confirmation by central pathology review. Laboratory analysis was performed at Brigham and Women's Hospital (Boston, MA). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) detected the presence of mutL homolog 1 (MLH1) and mutS homolog 2 (MSH2) proteins in primary tumor specimens. Patient cases were scored as positive (defined as ≥ 10% of tumor cells staining) or negative (< 10% tumor cells staining); MMR-D tumors had a negative IHC score for either MLH1 or MSH2, whereas MMR intact (MMR-I) tumors retained expression of both proteins.

DNA extracted from tumor was polymerase chain reaction amplified using the following microsatellite markers: BAT25, BAT26, D17S250, D5S346, ACTC, D18S55, BAT40, D10S197, BAT34c4, and MycL. Normal control tissue was obtained from a separate nontumor tissue block; otherwise, non-neoplastic control tissue was obtained by microdissection. Microdissection was performed when necessary to ensure greater than 60% tumor within the sample. Tumors were designated MSI-H if instability was identified at more than 50% of the loci screened, MSI low (MSI-L) if at least one but fewer than 50% of the loci showed instability, and microsatellite stable (MSS) if all loci were stable. For analysis, MSI-L and MSS patient cases were combined and designated as MMR-I. Genotyping and IHC results showed substantial agreement for both cohorts tested. Tumors classified as MMR-D either lacked expression of MLH1 or MSH2 by IHC or were MSI-H by genotyping.

18qLOH Determination

Tumor DNA was polymerase chain reaction amplified using the following 18q markers: D18S69, D18S64, D18S61, D18S58, and D18S55. 18qLOH was only scored in the absence of MSI-H (MMR-D by IHC or genotyping) and was defined as peak ratio of tumor to normal greater than 1.35 or less than 0.67 for any individual marker. Markers with monoallelic results or microsatellite instability were determined to be noninformative. Tumors were classified as having 18qLOH if two or more markers were informative and demonstrated this feature. Tumors were classified as 18q intact if two or more markers were informative and did not indicate LOH.

Statistical Methods

The primary study end point was OS measured from trial entry until death as a result of any cause. DFS was measured from study entry until documented disease progression or death as a result of any cause. Secondary goals determined whether tumor MMR or 18qLOH status identified better response to a particular study treatment. Relationships between tumor marker status and clinical pathologic factors were studied using Pearson χ2 and Satterthwaite t tests; continuous factors with more than two groups were tested using Wilcoxon rank sum test. In the combined data set, moderate to large DFS hazard ratios (HRs; > 1.7) were detectable for MMR with adequate power (> 0.7) with the numbers of DFS events observed (two-sided α = 0.025); only large DFS HRs (> 1.90) were detectable for 18qLOH. Differences detectable with adequate power for OS and within trial and treatment subgroups were even greater (> 2.0).

A Cox model tested interactions between study and marker status and treatment arm and marker status, and log-rank test compared survival among categories defined by marker status and study or treatment and within study, marker, and treatment subgroups. The proportional hazards model was used compare survival controlling for study, treatment, and other clinicopathologic factors. Graphical techniques and Schoenfeld residuals assessed the validity of model assumptions and model fit. The Kaplan-Meier method estimated the DFS and OS curves and 3- and 5-year survival probabilities. Pointwise CIs for the product limit estimate of the survival function were based on Greenwood's formula. All outcome analyses were conducted in the subset of patients in which MMR status was available by either IHC or genotyping, and data were analyzed with continued follow-up for DFS and OS as of December 4, 2009 (CALGB 9581), and November 9, 2009 (CALGB 89803).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Population

At least one marker was tested in specimens from 939 (54%) of the 1,738 patients randomly assigned in CALGB 9581 and 913 (72%) of the 1,264 patients enrolled onto CALGB 89803 (Figs 3A to 3C). For both studies combined, a total of 1,852 (62%) patients were tested for MMR status and 955 (32%; excludes those with MMR-D tumors) for 18qLOH. There was no imbalance in treatment assignment for either trial overall or for the MMR and 18qLOH analysis subsets (Table 1; Appendix Table A1, online only). Of tumors tested, technical issues (eg, insufficient tissue quality, allelic dropout) led to a 0.4% noninformative rate for MMR and 14.5% noninformative rate for 18qLOH testing.

Fig 3.

Association between marker status and treatment outcome. Results of analysis examining association between mismatch repair (MMR) and 18q status and protocol treatment outcome (disease-free survival [DFS] and overall survival [OS] denote Kaplan-Meier estimates at 5 years; P values are associated with the log-rank test). Cohorts included (A) stage II patients treated on Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 9581, (B) stage III patients treated on CALGB 89803, and (C) stage II and III patients treated on either CALGB 9581 or 89803. 18qLOH, loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q; MMR-D, mismatch repair deficiency; MMR-I, mismatch repair intact.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Characteristic | Stage II Patients: CALGB 9581 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMR-D |

18qLOH |

|||||||||

| Analyzed |

Not Analyzed |

P | Analyzed |

Not Analyzed |

P | |||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| No. of patients | 939 | 799 | 353 | 1,385 | ||||||

| Treatment | .35 | .039 | ||||||||

| MoAb 17-1A | 477 | 50.8 | 388 | 48.6 | 193 | 54.7 | 672 | 48.5 | ||

| Observation | 462 | 49.2 | 411 | 51.4 | 160 | 45.3 | 713 | 51.5 | ||

| Age, years | .09 | .74 | ||||||||

| Mean | 65 | 64 | 64 | 64 | ||||||

| Range | 30–90 | 24–88 | 33–89 | 24–90 | ||||||

| Sex | .62 | .23 | ||||||||

| Female | 447 | 47.6 | 390 | 48.8 | 160 | 45.3 | 677 | 48.9 | ||

| Male | 492 | 52.4 | 409 | 51.2 | 193 | 54.7 | 708 | 51.1 | ||

| Tumor location | .87 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Distal | 367 | 39.2 | 304 | 38.8 | 169 | 48.0 | 502 | 36.7 | ||

| Proximal | 569 | 60.1 | 479 | 61.2 | 183 | 52.0 | 865 | 63.3 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | .98 | .049 | ||||||||

| Well | 80 | 8.6 | 66 | 8.4 | 33 | 9.4 | 113 | 8.3 | ||

| Moderate | 709 | 70.0 | 596 | 75.8 | 278 | 79.2 | 1,027 | 75.0 | ||

| Poor/undifferentiated | 144 | 15.4 | 124 | 15.8 | 40 | 11.4 | 228 | 16.7 | ||

| Mean No. of nodes sampled | 14.0 | 14.8 | .12 | 13.6 | 14.6 | .07 | ||||

| Stage III Patients: CALGB 89803 |

||||||||||

| MMR-D |

18qLOH |

|||||||||

| Analyzed |

Not Analyzed |

Analyzed |

Not Analyzed |

|||||||

| No. |

% |

No. |

% |

P |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

P |

|

| No. of patients | 913 | 351 | 602 | 662 | ||||||

| Treatment | .65 | .78 | ||||||||

| FU/LV | 458 | 50.2 | 171 | 48.7 | 302 | 50.2 | 327 | 49.4 | ||

| IFL | 455 | 49.8 | 180 | 51.3 | 300 | 49.8 | 335 | 50.6 | ||

| Age, years | .97 | .91 | ||||||||

| Mean | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | ||||||

| Range | 21–85 | 26–82 | 24–85 | 21–85 | ||||||

| Sex | .25 | .33 | ||||||||

| Female | 415 | 45.5 | 147 | 41.9 | 2,590 | 43.0 | 303 | 45.8 | ||

| Male | 498 | 54.5 | 204 | 58.1 | 343 | 57.0 | 359 | 54.2 | ||

| Tumor location | .84 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Distal | 382 | 42.4 | 139 | 41.7 | 286 | 48.0 | 235 | 36.8 | ||

| Proximal | 519 | 57.6 | 194 | 58.3 | 310 | 52.0 | 403 | 63.2 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | .93 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Well | 50 | 5.5 | 20 | 6.0 | 32 | 5.4 | 38 | 6.0 | ||

| Moderate | 629 | 69.7 | 232 | 69.9 | 451 | 75.5 | 410 | 64.3 | ||

| Poor/undifferentiated | 224 | 24.8 | 80 | 24.1 | 114 | 19.1 | 190 | 29.8 | ||

| Positive nodes | .66 | .48 | ||||||||

| Mean | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.6 | ||||||

| Range | 1–29 | 0–22 | 1–24 | 0–29 | ||||||

| Nodal ratio | .44 | .43 | ||||||||

| Mean | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.30 | ||||||

| Range | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–1 | ||||||

| Nodes sampled | .14 | .019 | ||||||||

| Mean | 14.6 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 15 | ||||||

| Range | 1–99 | 1–68 | 1–99 | 1–68 | ||||||

Abbreviations: 18qLOH, loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q; CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; FU/LV, fluorouracil plus leucovorin; IFL, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan; MMR-D, mismatch repair deficiency; MoAb 17-1A, monoclonal antibody 17-1A.

Relationships Between Marker Status and Clinicopathologic Factors

Tumors with MMR-D were more proximally located and more poorly differentiated in both the stage II and III cohorts (Table 2). Stage III MMR-D tumors were more common in women than in men (55% v 45%; P = .020) and had a lower mean nodes ratio than MMR-I tumors (0.25 v 0.31; P = .005). Stage II cancers with 18qLOH were more likely to be in a distal location (51.4% v 38%; P = .046).

Table 2.

Marker Prevalence and Association With Histopathologic Variables

| Characteristic | Stage II Patients: CALGB 9581 |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMR Status |

18q Status |

|||||||||||

| Patients With MMR-D Tumors |

Patients With MMR-I Tumors |

P | Patients With 18q Intact |

Patients With 18qLOH Tumors |

Patients With Noninformative 18qLOH |

P | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| No. of patients | 199 | 736 | 71 | 222 | 60 | |||||||

| Treatment | .76 | .54 | ||||||||||

| MoAb 17-1A | 103 | 51.8 | 372 | 50.5 | 43 | 60.6 | 118 | 53.2 | 32 | 53.3 | ||

| Observation | 96 | 48.2 | 364 | 49.5 | 28 | 39.4 | 104 | 46.8 | 28 | 46.7 | ||

| Age, years | .24 | .66 | ||||||||||

| Mean | 65 | 64 | 63 | 65 | 64 | |||||||

| Range | 30–87 | 33–90 | 36–87 | 33–89 | 38–79 | |||||||

| Sex | .002 | .37 | ||||||||||

| Male | 85 | 42.7 | 405 | 55.0 | 35 | 49.3 | 121 | 54.5 | 37 | 61.7 | ||

| Female | 114 | 57.3 | 331 | 45.0 | 36 | 50.7 | 101 | 45.5 | 23 | 38.3 | ||

| Site of tumor | < .001 | .13 | ||||||||||

| Distal | 27 | 13.6 | 339 | 46.6 | 27 | 38.0 | 114 | 51.4 | 28 | 46.7 | ||

| Proximal | 72 | 86.4 | 394 | 53.5 | 44 | 62.0 | 107 | 48.2 | 32 | 53.3 | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 3 | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | ||||||

| Tumor differentiation | < .001 | .40 | ||||||||||

| Well | 12 | 6.0 | 68 | 9.2 | 6 | 8.4 | 21 | 9.5 | 6 | 10.0 | ||

| Moderate | 122 | 61.3 | 584 | 79.4 | 53 | 74.6 | 175 | 78.8 | 50 | 83.3 | ||

| Poor/undifferentiated | 64 | 32.2 | 79 | 10.7 | 12 | 16.9 | 25 | 11.3 | 3 | 5.0 | ||

| Unknown | 1 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.7 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 1.7 | |||

| Nodes sampled | < .001 | .24 | ||||||||||

| Mean | 16.6 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 13.8 | 11.8 | |||||||

| Range | 3–49 | 0–59 | 3–59 | 1–51 | 0–47 | |||||||

| Stage III Patients: CALGB 89803 |

||||||||||||

| MMR Status |

18q Status |

|||||||||||

| Patients With MMR-D Tumors |

Patients With MMR-I Tumors |

Patients With 18q Intact |

Patients With 18qLOH Tumors |

Patients With Noninformative 18qLOH |

||||||||

| No. |

% |

No. |

% |

P |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

P |

|

| No. of patients | 131 | 779 | 79 | 445 | 78 | |||||||

| Treatment | .47 | .58 | ||||||||||

| FU/LV | 62 | 47.3 | 395 | 50.7 | 39 | 49.4 | 228 | 51.2 | 35 | 44.9 | ||

| IFL | 69 | 52.7 | 384 | 49.3 | 40 | 50.6 | 217 | 48.8 | 43 | 55.1 | ||

| Age, years | .52 | .025 | ||||||||||

| Mean | 61 | 60 | 59 | 60 | 63 | |||||||

| Range | 21–85 | 24–85 | 35–80 | 24–85 | 39–85 | |||||||

| Sex | .020 | .82 | ||||||||||

| Male | 59 | 45 | 436 | 56 | 45 | 57.0 | 251 | 56.4 | 47 | 57.0 | ||

| Female | 72 | 55 | 343 | 44 | 34 | 43.0 | 194 | 43.6 | 31 | 43.0 | ||

| Site of tumor | < .001 | .69 | ||||||||||

| Distal | 14 | 10.7 | 366 | 47 | 39 | 49.37 | 208 | 46.7 | 39 | 50.0 | ||

| Proximal | 115 | 87.8 | 403 | 51.7 | 37 | 46.84 | 235 | 52.8 | 38 | 48.7 | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 1.5 | 10 | 1.3 | 3 | 3.8 | 2 | 0.4 | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | < .001 | .20 | ||||||||||

| Well | 2 | 1.5 | 48 | 6.2 | 0 | 26 | 5.8 | 6 | 7.8 | |||

| Moderate | 63 | 48.1 | 564 | 72.4 | 63 | 79.8 | 332 | 74.6 | 56 | 72.7 | ||

| Poor/undifferentiated | 64 | 48.9 | 159 | 20.4 | 13 | 16.5 | 86 | 19.3 | 15 | 19.5 | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 1.5 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | |||

| Positive nodes | .95 | .28 | ||||||||||

| Mean | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3.4 | 3.5 | |||||||

| Range | 1–23 | 1–29 | 1–16 | 1–24 | 1–23 | |||||||

| Nodal ratio | .005 | .64 | ||||||||||

| Mean | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.3 | 0.33 | |||||||

| SD | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.27 | |||||||

| Nodes sampled | .007 | .32 | ||||||||||

| Mean | 16.7 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 14.0 | 12.4 | |||||||

| Range | 2–68 | 1–99 | 4–45 | 1–99 | 1–27 | |||||||

Abbreviations: 18qLOH, loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q; CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; FU/LV, fluorouracil plus leucovorin; IFL, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan; MMR, mismatch repair; MMR-D, mismatch repair deficiency; MMR-I, mismatch repair intact; MoAb 17-1A, monoclonal antibody 17-1A; SD, standard deviation.

Stage-Associated Differences in Marker Prevalence

Comparison of the two study cohorts revealed stage-associated differences in marker prevalence (Appendix Table A2, online only). As expected from previous studies, more stage II tumors were MMR-D (21.3% v 14.4%; P < .001). Patient cases tested for 18qLOH were those that did not demonstrate MMR-D. Among these, fewer stage III tumors were intact at 18q (15.1% v 24.2%; P = .001). These relationships remained the same with and without correction for noninformative patient cases.

Prognostic Marker Evaluation

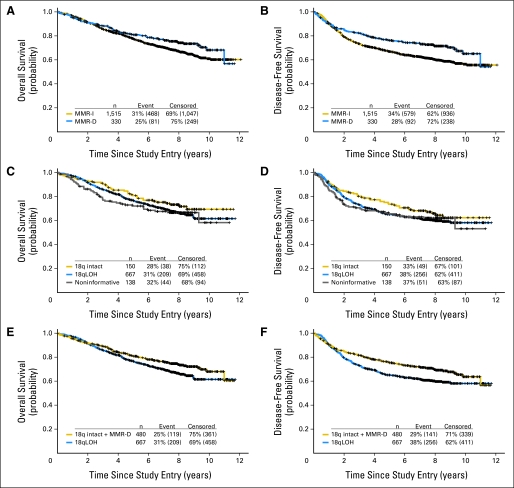

No significant interactions for DFS or OS were detected by testing for interaction between marker status and study for MMR and 18qLOH results. The relationships between marker status and outcome were then examined for the stage II and III study cohorts combined. Patients with MMR-D tumors experienced better 5-year DFS (0.76 v 0.67; HR, 0.69; log-rank P < .001) and 5-year OS (0.81 v 0.78; HR, 0.77; log-rank P = .029) than those with MMR-I tumors (Table 3; Figs 4A, 4B). Tumor 18qLOH status was not associated with a difference in outcome when patients of both stages were considered together (Figs 4C, 4D).

Table 3.

Effect of Tumor Marker Status for DFS and OS

| Treatment Group | No. of Patients | DFS |

OS |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Year DFS | 95% CI | Log-Rank P | HR | 95% CI | 5-Year OS | 95% CI | Log-Rank P | HR | 95% CI | ||

| All-patient analysis | 3,002 | 0.72 | 0.70 to 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.78 to 0.81 | ||||||

| All patients with MMR-I tumors | 1,515 | 0.67 | 0.64 to 0.69 | < .001 | 0.78 | 0.75 to 0.80 | .029 | ||||

| All patients with MMR-D tumors | 330 | 0.76 | 0.71 to 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.55 to 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.76 to 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.61 to 0.97 | ||

| All patients with 18q intact tumors | 150 | 0.74 | 0.66 to 0.80 | .18 | 0.81 | 0.73 to 0.86 | .18 | ||||

| All patients with 18qLOH tumors | 667 | 0.65 | 0.61 to 0.69 | 1.2 | 0.91 to 1.68 | 0.77 | 0.73 to 0.80 | 1.26 | 0.89 to 1.79 | ||

| All patients with noninformative 18qLOH | 138 | 0.66 | 0.57 to 0.73 | .39* | 1.01 | 0.97 to 1.05 | 0.72 | 0.63 to 0.79 | .30* | 1.02 | 0.98 to 1.06 |

| Stage II patients (CALGB 9581) | |||||||||||

| Stage II patients with MMR-I tumors | 736 | 0.75 | 0.72 to 0.78 | .008 | 0.84 | 0.81 to 0.86 | .12 | ||||

| Stage II patients with MMR-D tumors | 199 | 0.84 | 0.77 to 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.47 to 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.81 to 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.54 to 1.07 | ||

| Stage II patients with 18q intact tumors | 71 | 0.77 | 0.65 to 0.86 | .90 | 0.82 | 0.70 to 0.89 | .78 | ||||

| Stage II patients with 18qLOH tumors | 222 | 0.79 | 0.73 to 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.62 to 1.73 | 0.87 | 0.82 to 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.53 to 1.61 | ||

| All patients with noninformative 18qLOH | 60 | 0.80 | 0.67 to 0.89 | .79* | 0.98 | 0.91 to 1.05 | 0.85 | 0.73 to 0.92 | .85* | 0.98 | 0.91 to 1.06 |

| Stage III patients (CALGB 89803) | |||||||||||

| Stage III patients with MMR-I tumors | 779 | 0.59 | 0.56 to 0.63 | .20 | 0.72 | 0.68 to 0.75 | .42 | ||||

| Stage III patients with MMR-D tumors | 131 | 0.65 | 0.56 to 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.60 to 1.11 | 0.72 | 0.64 to 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.63 to 1.22 | ||

| Stage III patients with 18q intact tumors | 79 | 0.70 | 0.59 to 0.79 | .32 | 0.80 | 0.69 to 0.87 | .17 | ||||

| Stage III patients with 18qLOH tumors | 445 | 0.58 | 0.54 to 0.63 | 1.22 | 0.83 to 1.78 | 0.72 | 0.67 to 0.76 | 1.38 | 0.87 to 2.17 | ||

| All patients with noninformative 18qLOH | 78 | 0.55 | 0.43 to 0.65 | .24* | 1.03 | 0.99 to 1.08 | 0.62 | 0.50 to 0.72 | .09* | 1.04 | 1.00 to 1.09 |

Abbreviations: 18qLOH, loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q; CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; MMR-D, mismatch repair deficiency; MMR-I, mismatch repair intact; OS, overall survival.

Statistics when tested as a third group with the 18qLOH tumors and 18qLOH intact tumors.

Fig 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for the combined data set of stage II (Cancer and Leukemia Group B [CALGB] 9581) and stage III (CALGB 89803) patients, representing comparisons between different marker-defined subsets. (A) Overall survival (OS; all-cause death) by mismatch repair (MMR) status (log-rank P = .029); (B) disease-free survival (DFS; documented recurrence of primary colon cancer or death as a result of any cause) by MMR status (log-rank P < .001); (C) OS by 18q status (log-rank P = .32); (D) DFS by 18q status (log-rank P = .39); (E) OS by 18q status with MMR deficiency (MMR-D) included among 18q intact (log-rank P = .021); (F) DFS by 18q status with MMR-D included among 18q intact (log-rank P = .002). 18qLOH, loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q; MMR-I, mismatch repair intact.

The prognostic significance of the markers was examined for each trial independently. Among patients with stage II disease (CALGB 9581), those with MMR-D tumors experienced significantly better DFS than those with MMR-I tumors (Table 3; 0.84 v 0.75; HR, 0.65; P = .008). This association was similar for OS; however, statistical significance was not reached (0.86 v 0.84; P = .12). The presence of tumor 18qLOH was not prognostic for patients with stage II disease. In patients with stage III disease (CALGB 89803), neither tumor MMR status nor 18qLOH was associated with a significant difference in treatment outcome.

Most studies of the relationship between tumor 18q status and clinical behavior have excluded MMR-D patient cases from comparisons between 18qLOH and 18q intact patient cases.12–22 However, in a few often-cited reports, MSI-H patient cases were analyzed together with others that showed no 18qLOH.4,9,23 To compare our results with those from these earlier studies, we combined the MMR-D and the 18q intact patient cases and studied differences in outcome between these patients and those whose tumors had 18qLOH (Figs 4E, 4F). This analysis showed significantly worse 5-year DFS and OS for patients whose tumors demonstrated 18qLOH. In the combined cohort of stage II and III patients, 5-year DFS was 0.65 (95% CI, 0.61 to 0.69) versus 0.75 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.79; log-rank P = .021), and OS was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.73 to 0.80) versus 0.81 (95% CI, 0.77 to 0.84; log-rank P = .002), for those with and without 18qLOH, respectively.

The following variables were considered simultaneously in a regression model with MMR: study, sex, age, performance status, race, tumor location, tumor grade, number of nodes sampled, tumor invasion depth, and extramural vascular invasion. Of these, study, sex, age at study entry, performance status, tumor grade, number of nodes sampled, tumor invasion depth, and extramural vascular invasion were significantly related to DFS and OS (Appendix Table A3, online only). MMR-D remained significant for DFS (P = .012) and OS (P = .016) when other prognostic variables were considered in the respective models. Enrollment onto study CALGB 9581, female sex, having more nodes examined, and tumor MMR-D decreased the risk of recurrence or death. All other variables increased the risk of recurrence or death as they increased in value.

Predictive Marker Evaluation

Neither CALGB 9581 nor CALGB 89803 demonstrated significant differences in outcome between study treatment arms. When we examined the relationship between study treatment and marker status, neither MMR-D nor 18qLOH predicted better response to a particular regimen (Table 4). An earlier report from CALGB 89803 examined the association between tumor MMR-D status and response to adjuvant chemotherapy and found improved DFS in patients receiving IFL whose tumors were MMR-D.24 The analysis presented here uses an available IHC result preferentially over an available genotyping result, whereas the previous paper reported results in the subset of patients with agreement between IHC and genotyping. Consequently, the number of patients with MMR results was increased from 702 in the previous study to 913 in the current study. Using the updated data set for patients with agreement between IHC and genotyping results, a significant interaction between MMR status and treatment in stage III patients continued to be observed (interaction HR, 0.41; P = .026).

Table 4.

Effect of Tumor Marker Status on Treatment Outcome for DFS and OS

| Treatment Group | No. of Patients | DFS |

OS |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Year DFS | 95% CI | Log-Rank P | HR | 95% CI | 5-Year OS | 95% CI | Log-Rank P | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Stage II predictive analysis | |||||||||||

| Patients with MSI deficient tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with MoAb 17-1A | 103 | 0.86 | 0.77 to 0.91 | .52 | 0.87 | 0.79 to 0.93 | .52 | ||||

| Observation | 96 | 0.82 | 0.72 to 0.88 | 1.21 | 0.68 to 2.18 | 0.86 | 0.77 to 0.91 | 1.22 | 0.66 to 2.26 | ||

| Patients with MSI intact tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with MoAb 17-1A | 372 | 0.74 | 0.70 to 0.79 | .75 | 0.85 | 0.81 to 0.88 | .84 | ||||

| Observation | 364 | 0.76 | 0.71 to 0.80 | 0.96 | 0.74 to 1.24 | 0.83 | 0.79 to 0.87 | 1.03 | 0.78 to 1.37 | ||

| Patients with 18qLOH tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with MoAb 17-1A | 118 | 0.76 | 0.67 to 0.83 | .06 | 0.88 | 0.80 to 0.92 | .26 | ||||

| Observation | 104 | 0.83 | 0.74 to 0.89 | 0.61 | 0.36 to 1.03 | 0.86 | 0.78 to 0.92 | 0.72 | 0.40 to 1.28 | ||

| Patients with 18q intact tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with MoAb 17-1A | 43 | 0.74 | 0.57 to 0.85 | .99 | 0.82 | 0.66 to 0.91 | .60 | ||||

| Observation | 28 | 0.82 | 0.61 to 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.40 to 2.50 | 0.81 | 0.61 to 0.92 | 1.29 | 0.50 to 3.34 | ||

| Patients with noninformative tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with MoAb 17-1A | 32 | 0.80 | 0.61 to 0.91 | .91 | 0.83 | 0.64 to 0.95 | .81 | ||||

| Observation | 28 | 0.80 | 0.58 to 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.32 to 2.80 | 0.88 | 0.67 to 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.26 to 2.84 | ||

| Stage III predictive analysis | |||||||||||

| Patients with MMR-D tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with FU/LV | 62 | 0.60 | 0.46 to 0.71 | .18 | 0.71 | 0.57 to 0.81 | .62 | ||||

| Treated with IFL | 69 | 0.69 | 0.57 to 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.38 to 1.20 | 0.74 | 0.61 to 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.46 to 1.59 | ||

| Patients with MMR-I tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with FU/LV | 395 | 0.61 | 0.56 to 0.65 | .44 | 0.73 | 0.68 to 0.77 | .78 | ||||

| Treated with IFL | 384 | 0.58 | 0.52 to 0.62 | 1.09 | 0.88 to 1.34 | 0.70 | 0.65 to 0.74 | 1.03 | 0.82 to 1.31 | ||

| Patients with 18qLOH tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with FU/LV | 228 | 0.58 | 0.51 to 0.64 | .49 | 0.72 | 0.66 to 0.78 | .39 | ||||

| Treated with IFL | 217 | 0.59 | 0.52 to 0.65 | 0.90 | 0.68 to 1.20 | 0.71 | 0.65 to 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.64 to 1.19 | ||

| Patients with 18q intact tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with FU/LV | 39 | 0.72 | 0.55 to 0.83 | .63 | 0.79 | 0.62 to 0.89 | .54 | ||||

| Treated with IFL | 40 | 0.69 | 0.52 to 0.81 | 1.20 | 0.58 to 2.45 | 0.81 | 0.64 to 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.32 to 1.81 | ||

| Patients with noninformative tumors | |||||||||||

| Treated with MoAb 17-1A | 35 | 0.60 | 0.42 to 0.74 | .51 | 0.69 | 0.50 to 0.81 | .57 | ||||

| Observation | 43 | 0.51 | 0.35 to 0.65 | 1.24 | 0.65 to 2.37 | 0.57 | 0.40 to 0.70 | 1.22 | 0.61 to 2.44 | ||

Abbreviations: 18qLOH, loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q; DFS, disease-free survival; FU/LV, fluorouracil plus leucovorin; HR, hazard ratio; IFL, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan; MMR-D, mismatch repair deficiency; MMR-I, mismatch repair intact; MoAb 17-1A, monoclonal antibody 17-1A; MSI, microsatellite instability; OS, overall survival.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms an association between tumor MMR status and CRC clinical behavior, showing that tumors with MSI-H are less likely to metastasize or recur after surgery. These data also indirectly support those of other stage III colon cancer adjuvant trials, suggesting that patients with MMR-D tumors do not benefit from FU-based treatment.6,7 In our study, the association between favorable outcome and MMR-D status was significant for DFS in the stage II cohort alone and in the stages II and III combined analysis but not in the stage III cohort. Because none of the stage II and all of the stage III patients received adjuvant chemotherapy containing FU, it is possible that better outcome for the MMR-D stage III subset was not observed because it was negated by MMR-D–associated lack of response to FU. In addition, for the stage II patients, DFS but not OS was better for patients whose tumors were MMR-D. This would be explained if the patients with MMR-D tumors whose disease recurred went on to receive, and not benefit from, second-line chemotherapy containing FU.

The region of 18q lost during CRC development contains a number of important tumor suppressor genes.25–27 Losses of 18q alleles were first associated with CRC treatment outcome in a 1996 retrospective analysis of DCC protein expression by Shibata et al.28 Although a large number of subsequent studies have examined the relationship between 18qLOH and CRC clinical outcome, the results are difficult to interpret. Available reports are almost equally divided between those finding that tumor 18qLOH predicted poor survival4,9,14–16,23,26,29–32 and those showing no association between tumor 18q status and treatment outcome.12,13,17,19–21,33–36 Most studies involved retrospective analysis of archival specimens from surgical cohorts, with only four studies reporting retrospective analyses of tumors from patients participating in either a randomized treatment trial or prospective cohort study. Of these, one found worse outcome for patients with 18qLOH-positive tumors,4 one reported better outcome for a subset of patients with 18qLOH-positive tumors,18 and two found no association between 18q status and outcome.17,19 Finally, two prospective clinical trials studied the relationship between tumor 18q status and outcome as secondary end points in a colon cancer treatment study.20,21 Neither of these studies found a significant association between tumor 18q status and outcome.

One reason for difficulty interpreting the data on the association between tumor 18q loss and clinical response has been confusion introduced by variable assignment of the MMR-D subset. Two early studies showing an association between 18qLOH and poor treatment outcome included patients with MMR-D tumors as well as those with 18q intact tumors and compared this combined group with patients whose tumors demonstrated 18qLOH.4,9 Given the better outcome among the MMR-D patient cases, the 18q result could have been affected by confounding. This issue was addressed by Halling et al,17 who found worse outcome in patients with 18qLOH tumors when compared with a combined group of patients with 18q intact and MMR-D tumors. For this study, prognostic significance of tumor 18qLOH was no longer present when the patients with MMR-D tumors were excluded. The results of our study are in agreement with those of Halling et al and show that independent of MMR-D status, tumor 18qLOH determination does not have prognostic significance.

In a previous analysis of CALGB 89803, we found that patients with MMR-D tumors who received IFL experienced improved treatment outcome, with 5-year DFS of 0.76 versus 0.59 (P = .03) and OS of 0.78 versus 0.70 (P = .23). When a predictive analysis was conducted within the MMR-D/MSI-H tumor subtype, this result failed to achieve significance (DFS, P = .07; OS, P = .27; n = 96). In the current analysis, MMR status was determined using an algorithm that selected the IHC result when available and the genotyping result when no IHC result was available. This increased the sample size by more than 200 patients to the 913 patients in the current study, and follow-up was also updated to November 9, 2009. In this updated analysis, we continued to observe a marginally significant increase in DFS among patients with MMR-D tumors treated with IFL versus patients with MMR-I tumors treated with IFL (P = .055). The interaction HR for MMR status by treatment using this definition was 0.612 (P = .12). However, when MMR/MSI status was defined based on agreement between IHC and genotyping results, as previously reported, we again observed a significant interaction of MMR/MSI status by treatment (interaction HR, 0.418; P = .026). Thus, the previous results were strengthened with additional follow-up.

In conclusion, we found that patients with MMR-D stage II colon cancers had improved outcome after surgical resection. Analysis of tumor 18q status was of prognostic value for neither stage II nor III patient cases. Finally, neither of these markers predicted differential response to either adjuvant chemotherapy with edrecolomab or IFL,and additional study is required to understand the benefit of FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with MMR-D colon cancer.

Acknowledgment

Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) would like to thank Hejin Hahn, MD, for assistance with microsatellite instability tissue analyses and Scott Jewell, PhD, for oversight of the CALGB tissue repository at Ohio State University. These trials were conducted in participation with the North Central Cancer Treatment Group, National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Southwest Oncology Group, Cancer Research United Kingdom Clinical Trials Unit, and the National Cancer Institute Cancer Trials Support Unit.

The following institutions participated in this study: Baptist Cancer Institute Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP), Memphis, TN—Lee S. Schwartzberg, MD, supported by Grant No. CA71323; CALGB Statistical Center, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC—Stephen George, PhD, supported by Grant No. CA33601; Cancer Centers of the Carolinas, Greenville, SC—Jeffrey K. Giguere, MD, supported by Grant No. CA29165; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA—Alan T. Lefor, MD; Christiana Care Health Services CCOP, Wilmington, DE—Stephen Grubbs, MD, supported by Grant No. CA45418; Community Hospital Syracuse CCOP, Syracuse, NY—Jeffrey Kirshner, MD, supported by Grant No. CA45389; Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA—Harold J Burstein, MD, PhD, supported by Grant No. CA32291; Dartmouth Medical School–Norris Cotton Cancer Center, Lebanon, NH—Konstantin Dragnev, MD, supported by Grant No. CA04326; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC—Jeffrey Crawford, MD, supported by Grant No. CA47577; Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC—Minetta C. Liu, MD, supported by Grant No. CA77597; Grand Rapids Clinical Oncology Program, Grand Rapids, MI—Martin J. Bury, MD; Green Mountain Oncology Group CCOP, Bennington, VT—Herbert L. Maurer, MD, supported by Grant No. CA35091; Greenville CCOP, Cancer Centers of the Carolinas, Greenville, SC; Heartland Cancer Research CCOP, St Louis, MO—Alan P. Lyss, MD, supported by Grant No. CA114558 (Missouri Baptist); Hematology-Oncology Associates of Central New York CCOP, Syracuse, NY—Jeffrey Kirshner, MD, supported by Grant No. CA45389; Illinois Oncology Research Association, Peoria, IL—John W. Kugler, MD, supported by Grant No. CA35113; Kaiser Permanente CCOP, San Diego, CA—Han A. Koh, MD, supported by Grant No. CA45374; Kansas City Community Clinical Oncology Program CCOP, Kansas City, MO—Rakesh Gaur, MD; Long Island Jewish Medical Center, Lake Success, NY—Kanti R. Rai, MD, supported by Grant No. CA35279; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA—Jeffrey W. Clark, MD, supported by Grant No. CA32291; McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada—Gerald Batist, MD; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC—Mark Green, MD, supported by Grant No. CA03927; Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY—Clifford A. Hudis, MD, supported by Grant No. CA77651; Missouri Valley Consortium CCOP, Omaha, NE—Gamini S. Soori, MD; Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami, FL—Rogerio C. Lilenbaum, MD, supported by Grant No. CA45564; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY—Lewis R. Silverman, MD, supported by Grant No. CA04457; Nevada Cancer Research Foundation CCOP, Las Vegas, NV—John A. Ellerton, MD, supported by Grant No. CA35421; North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System, New Hyde Park, NY—Daniel Budman, MD, supported by Grant No. CA35279; NorthShore University HealthSystem CCOP, Evanston, IL—David L. Grinblatt, MD; Northern Indiana Cancer Research Consortium CCOP, South Bend, IN—Rafat Ansari, MD, supported by Grant No. CA86726; Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI—William Sikov, MD, supported by Grant No. CA08025, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY—Ellis Levine, MD, supported by Grant No. CA59518; Southeast Cancer Control Consortium CCOP, Goldsboro, NC—James N. Atkins, MD, supported by Grant No. CA45808; State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY—Stephen L. Graziano, MD, supported by Grant No. CA21060; The Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH—Clara D. Bloomfield, MD, supported by Grant No. CA77658; University of Alabama Birmingham, Birmingham, AL—Robert Diasio, MD, supported by Grant No. CA47545; University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA—Barbara A. Parker, MD, supported by Grant No. CA11789; University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA—Charles J. Ryan, MD, supported by Grant No. CA60138; University of Chicago, Chicago, IL—Hedy L. Kindler, MD, supported by Grant No. CA41287; University of Illinois Minority-Based CCOP, Chicago, IL—David J. Peace, MD, supported by Grant No. CA74811; University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA—Daniel A. Vaena, MD, supported by Grant No. CA47642; University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center, Baltimore, MD—Martin Edelman, MD, supported by Grant No. CA31983; University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA—William V. Walsh, MD, supported by Grant No. CA37135; University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN—Bruce A. Peterson, MD, supported by Grant No. CA16450; University of Missouri/Ellis Fischel Cancer Center, Columbia, MO—Michael C. Perry, MD, supported by Grant No. CA12046; University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE—Anne Kessinger, MD, supported by Grant No. CA77298; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC—Thomas C. Shea, MD, supported by Grant No. CA47559; University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, OK—Shubham Pant, MD, supported by Grant No. CA37447; University of Tennessee Memphis, Memphis, TN—Harvey B. Niell, MD, supported by Grant No. CA47555; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX—Debasish Tripathy, MD; University of Vermont, Burlington, VT—Steven M. Grunberg, MD, supported by Grant No. CA77406; Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center CCOP, Richmond, VA—John D. Roberts, MD, supported by Grant No. CA52784; Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC—David D. Hurd, MD, supported by Grant No. CA03927; Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC—Brendan M. Weiss, MD, supported by Grant No. CA26806; Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO—Nancy Bartlett, MD, supported by Grant No. CA77440; Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY—John Leonard, MD, supported by Grant No. CA07968; Western Pennsylvania Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, PA—John Lister, MD; Yale University, New Haven, CT—W. Kevin Kelly, DO, supported by Grant No. CA16359; New Hampshire Oncology-Hematology, Concord, NH—Douglas J. Weckstein; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Philadelphia, PA—Robert L. Comis, MD, chairman, supported by Grant No. CA21115; Southwest Oncology Group, San Antonio, TX—Laurence H. Baker, DO, chairman, supported by Grant No. CA32102; North Central Cancer Treatment Group, Rochester, MN—Jan Buckner, MD, chairman, supported by Grant No. CA25224; The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project, Pittsburgh, PA—Norman Wolmark, MD, supported by Grant No. CA12027; National Cancer Institute of Canada, Toronto, Ontario, Canada—Elizabeth Eisenhauer, MD, president, supported by Grant No. CA77202; and Radiation Therapy Oncology Group, Philadelphia, PA—Walter J. Curran Jr, supported by Grant No. CA21661.

Appendix

Table A1.

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Characteristic | Stage II Patients: CALGB 9581 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients |

Patients With Tumors Analyzed for MMR-D |

Patients With Tumors Analyzed for 18qLOH |

||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| No. of patients | 1,738 | 939 | 353 | |||

| Treatment | ||||||

| MoAb 17-1A | 865 | 49.8 | 477 | 50.8 | 193 | 54.7 |

| Observation | 873 | 50.2 | 462 | 49.2 | 160 | 45.3 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean | 64 | 65 | 64 | |||

| Range | 24–90 | 30–90 | 33–89 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 837 | 48.2 | 447 | 47.6 | 160 | 45.3 |

| Male | 901 | 51.8 | 492 | 52.4 | 193 | 54.7 |

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Distal | 671 | 38.6 | 367 | 39.1 | 169 | 47.9 |

| Proximal | 1,048 | 60.3 | 569 | 60.6 | 183 | 51.8 |

| Unknown | 19 | 1.1 | 3 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Tumor differentiation | ||||||

| Well | 146 | 8.4 | 80 | 8.5 | 33 | 9.4 |

| Moderate | 1,305 | 75.1 | 709 | 75.5 | 278 | 78.8 |

| Poor | 262 | 15.1 | 140 | 14.9 | 40 | 11.3 |

| Undifferentiated | 6 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.4 | 0 | |

| Unknown | 19 | 1.1 | 6 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Mean nodes sampled | 14.4 | 14.1 | 13.6 | |||

| Stage III Patients: CALGB 89803 |

||||||

| All Patients |

Patients With Tumors Analyzed for MMR-D |

Patients With Tumors Analyzed for 18qLOH |

||||

| No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

| No. of patients | 1,264 | 913 | 602 | |||

| Treatment | ||||||

| FU/LV | 629 | 49.8 | 458 | 50.2 | 302 | 50.2 |

| IFL | 635 | 50.3 | 455 | 49.8 | 300 | 49.8 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean | 60 | 60 | 60 | |||

| Range | 21–85 | 21–85 | 24–85 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 562 | 44.5 | 415 | 45.5 | 259 | 43.0 |

| Male | 702 | 55.5 | 498 | 54.5 | 343 | 57.0 |

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Distal | 521 | 41.2 | 382 | 41.8 | 286 | 47.5 |

| Proximal | 713 | 56.4 | 519 | 56.8 | 310 | 51.5 |

| Unknown | 30 | 2.4 | 12 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.0 |

| Tumor differentiation | ||||||

| Well | 70 | 5.5 | 50 | 5.5 | 32 | 5.3 |

| Moderate | 861 | 68.1 | 629 | 68.9 | 451 | 74.9 |

| Poor | 299 | 23.7 | 220 | 24.1 | 112 | 18.6 |

| Undifferentiated | 5 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.3 |

| Unknown | 29 | 2.3 | 10 | 1.1 | 5 | 0.8 |

| Positive nodes | ||||||

| Mean | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 | |||

| Range | 1–29 | 1–29 | 1–24 | |||

| Nodal ratio | ||||||

| Mean | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.31 | |||

| Range | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–1 | |||

| Nodes sampled | ||||||

| Mean | 14.4 | 14.6 | 13.8 | |||

| Range | 1–99 | 1–99 | 1–99 | |||

Abbreviations: 18qLOH, loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q; CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; FU/LV, fluorouracil plus leucovorin; IFL, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan; MMR-D, mismatch repair deficiency; MoAb 17-1A, monoclonal antibody 17-1A.

Table A2.

Frequencies of Specimens Analyzed for Each Marker by Stage

| Characteristic | All Patients |

Stage II |

Stage III |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| No. of patients | 3,002 | 1,738 | 1,264 | |||

| Patient cases analyzed for MMR | ||||||

| MMR-I | 1,515 of 1,852 | 81.8 | 736 of 939 | 78.4 | 779 of 913 | 85.3 |

| MMR-D | 330 of 1,852 | 17.8 | 199 of 939 | 21.2 | 131 of 913 | 14.4 |

| MMR noninformative | 7 of 1,852 | 0.4 | 4 of 939 | 0.4 | 3 of 913 | 0.3 |

| Patient cases informative for MMR | ||||||

| MMR-I | 1,515 of 1,845 | 82.1 | 736 of 935 | 78.7 | 779 of 910 | 85.6 |

| MMR-D | 330 of 1,845 | 17.9 | 199 of 935 | 21.3 | 131 of 910 | 14.4 |

| Patient cases analyzed for 18qLOH | ||||||

| 18q intact | 150 of 955 | 15.7 | 71 of 353 | 20.1 | 79 of 602 | 13.1 |

| 18qLOH present | 667 of 955 | 69.8 | 222 of 353 | 62.9 | 445 of 602 | 73.9 |

| 18qLOH noninformative | 138 of 955 | 14.5 | 60 of 353 | 17.0 | 78 of 602 | 13.0 |

| Patient cases informative for 18qLOH | ||||||

| 18q intact | 150 of 817 | 18.4 | 71 of 293 | 24.2 | 79 of 524 | 15.1 |

| 18qLOH present | 667 of 817 | 81.6 | 222 of 293 | 75.8 | 445 of 524 | 84.9 |

| Patient cases not analyzed for MMR or LOH18q | 1,150 of 3,002 | 38.3 | 799 of 1,738 | 50.0 | 351 of 1,264 | 27.8 |

Abbreviations: 18qLOH, loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q; MMR, mismatch repair; MMR-D, mismatch repair deficiency; MMR-I, mismatch repair intact.

Table A3.

Multivariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors for DFS and OS

| Factor | DFS* |

OS† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P‡ | HR | 95% CI | P‡ | |

| Stage (II v III) | 0.56 | 0.47 to 0.66 | < .001 | 0.55 | 0.46 to 0.66 | < .001 |

| Sex (F v M) | 0.85 | 0.73 to 1.00 | .05 | 0.78 | 0.65 to 0.93 | .0055 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.017 | 1.01 to 1.02 | < .001 | 1.02 | 1.01 to 1.03 | < .001 |

| Performance status (0 v 1 v 2) | 1.39 | 1.18 to 1.63 | < .001 | 1.47 | 1.23 to 1.76 | < .001 |

| Tumor grade (I v II v III/IV) | 1.29 | 1.10 to 1.50 | .0014 | 1.38 | 1.16 to 1.64 | < .001 |

| No. of nodes sampled (continuous) | 0.98 | 0.97 to 0.99 | < .001 | 0.98 | 0.97 to 0.99 | .008 |

| Depth of tumor invasion (Tis/T1/T2 v T3 v T4a/T4b) | 1.66 | 1.35 to 2.04 | < .001 | 1.83 | 1.45 to 2.31 | < .001 |

| Extramural vascular invasion (yes v no) | 1.26 | 1.05 to 1.51 | .012 | 1.35 | 1.11 to 1.65 | .0025 |

| Mismatch repair deficiency (yes v no) | 0.76 | 0.62 to 0.94 | .012 | 0.75 | 0.59 to 0.94 | .016 |

Abbreviations: DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival.

DFS: n = 1,813; 660 events.

OS: n = 1,813; 539 events.

χ2.

Footnotes

See accompanying article on page 3146

Supported in part by Grants No. CA31946 from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, to CALGB (M.M.B.) and No. CA33601 to the CALGB Statistical Center (Daniel J. Sargent, Group Statistician and principal investigator).

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00002968.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Leonard B. Saltz, Genzyme (C), Assuragen (C), Genomic Health (U), Illumina Diagnostics (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Monica M. Bertagnolli, Mark Redston, Donna Niedzwiecki, Robert J. Mayer, Richard M. Goldberg, Thomas A. Colacchio, Robert S. Warren

Financial support: Monica M. Bertagnolli, Robert S. Warren

Administrative support: Monica M. Bertagnolli, Robert S. Warren

Provision of study materials or patients: Robert S. Warren

Collection and assembly of data: Monica M. Bertagnolli, Mark Redston, Carolyn C. Compton, Donna Niedzwiecki

Data analysis and interpretation: Monica M. Bertagnolli, Mark Redston, Carolyn C. Compton, Donna Niedzwiecki, Robert J. Mayer, Leonard B. Saltz, Robert S. Warren

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3219–3226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thibodeau S, Bren G, Schaid D. Microsatellite instability in cancer of the proximal colon. Science. 1993;260:616–619. doi: 10.1126/science.8484122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watanabe T, Wu TT, Catalano PJ, et al. Molecular predictors of survival after adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1196–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104193441603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samowitz WS, Curtin K, Ma KN, et al. Microsatellite instability in sporadic colon cancer is associated with an improved prognosis at the population level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:917–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:247–257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Thibodeau SN, et al. Confirmation of deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) as a predictive marker for lack of benefit from 5-FU based chemotherapy in stage II and III colon cancer: A pooled molecular reanalysis of randomized chemotherapy trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:180s. suppl; abstr 4008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerr D, Gray R, Quirke P, et al. A quantitative multigene RT-PCR assay for prediction of recurrence in stage II colon cancer: Selection of the genes in four large studies and results of the independent, prospectively designed QUASAR validation study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. suppl; abstr 4000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jen J, Kim H, Piantadosi S, et al. Allelic loss of chromosome 18q and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:213–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407283310401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saltz LB, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Irinotecan fluorouracil plus leucovorin is not superior to fluorouracil plus leucovorin alone as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer: Results of CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3456–3461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niedzwiecki D, Bertagnolli MM, Warren RS, et al. Documenting the natural history of patients with resected stage II adenocarcinoma of the colon after random assignment to adjuvant treatment with edrecolomab or observation: Results of CALGB 9581. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3146–3152. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang SC, Lin JK, Lin TC, et al. Loss of heterozygosity: An independent prognostic factor of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:778–784. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i6.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zauber NP, Wang C, Lee PS, et al. Ki-ras gene mutations, LOH of the APC and DCC genes, and microsatellite instability in primary colorectal carcinoma are not associated with micrometastases in pericolonic lymph nodes or with patients' survival. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:938–942. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.017814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogunbiyi OA, Goodfellow PJ, Herforth K, et al. Confirmation that chromosome 18q allelic loss in colon cancer is a prognostic indicator. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:427–433. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jernvall P, Mäkinen MJ, Karttunen TJ, et al. Loss of heterozygosity at 18q21 is indicative of recurrence and therefore poor prognosis in a subset of colorectal cancers. Br J Cancer. 1998;79:903–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi SW, Lee KJ, Bae YA, et al. Genetic classification of colorectal cancer based on chromosomal loss and microsatellite instability predicts survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2311–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halling KC, French AJ, McDonnell SK, et al. Microsatellite instability and 8p allelic imbalance in stage B2 and C colorectal cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1295–1303. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.15.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barratt PL, Seymour MT, Stenning SP, et al. DNA markers predicting benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil in patients with colon cancer: A molecular study. Lancet. 2002;360:1381–1391. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogino S, Nosho K, Irahara N, et al. Prognostic significance and molecular associations of 18q loss of heterozygosity: A cohort study of microsatellite stable colorectal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4591–4598. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popat S, Zhao D, Chen Z, et al. Relationship between chromosome 18q status and colorectal cancer prognosis: A prospective blinded analysis of 280 patients. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:627–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth AD, Tejpar S, Yan P, et al. Stage-specific prognostic value of molecular markers in colon cancer: Results of the translational study on the PETACC 3-EORTC 40993-SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:169s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3452. suppl; abstr 4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez-López E, Abad A, Font A, et al. Allelic loss on chromosome 18q as a prognostic marker in stage II colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1180–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanza G, Matteuzzi M, Gafá R, et al. Chromosome 18q allelic loss and prognosis in stage II and III colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 1998;79:390–395. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980821)79:4<390::aid-ijc14>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertagnolli MM, Niedzwiecki D, Compton CC, et al. Microsatellite instability predicts improved response to adjuvant therapy with irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in stage III colon cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Protocol 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1814–1821. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fearon ER, Cho KR, Nigro JM, et al. Identification of a chromosome 18q gene that is altered in colorectal cancers. Science. 1990;247:49–56. doi: 10.1126/science.2294591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alazzouzi H, Alhopuro P, Salovaara R, et al. SMAD4 as a prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2606–2611. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eppert K, Scherer SW, Ozcelik H, et al. MADR2 maps to 18q21 and encodes a TGF-beta-regulated MAD-related protein that is functionally mutated in colorectal carcinoma. Cell. 1996;86:543–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shibata D, Reale MA, Lavin P, et al. The DCC protein and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1727–1732. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612053352303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kern SE, Fearon ER, Kasper WF, et al. Allelic loss in colorectal carcinoma. JAMA. 1989;261:3099–3103. doi: 10.1001/jama.261.21.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Font A, Abad A, Monzó M, et al. Prognostic value of K-ras mutations and allelic imbalance on chromosome 18q in patients with resected colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:549–557. doi: 10.1007/BF02234328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diep CB, Thorstensen L, Meling GI, et al. Genetic tumor markers with prognostic impact in Dukes' states B and C colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:820–829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laurent-Puig P, Olschwang S, Delattre O, et al. Survival and acquired genetic alterations in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1136–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carethers JM, Hawn MT, Greenson JK, et al. Prognostic significance of allelic loss at chromosome 18q21 for stage II colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1188–1195. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70424-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindforss U, Fredholm H, Papadoglannakis N, et al. Allelic loss is heterogeneous throughout the tumor in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:2661–2667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bisgaard ML, Jäger AC, Dalgaard P, et al. Allelic loss of chromosome 2p21-16.3 is associated with reduced survival in sporadic colorectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:405–409. doi: 10.1080/003655201300051252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]