ABSTRACT

Purpose: Fatigue is one of the most frequent debilitating symptoms reported by people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on haemodialysis (HD) therapy. A wide range of underlying abnormalities, including skeletal muscle weakness, have been implicated as causes of this fatigue. Skeletal muscle weakness is well established in this population, and such muscle weakness is amenable to physical therapy treatment. The purpose of this review was to identify morphological, electrophysiological, and metabolic characteristics of skeletal muscles in people with ESRD/HD that may cause skeletal muscle weakness.

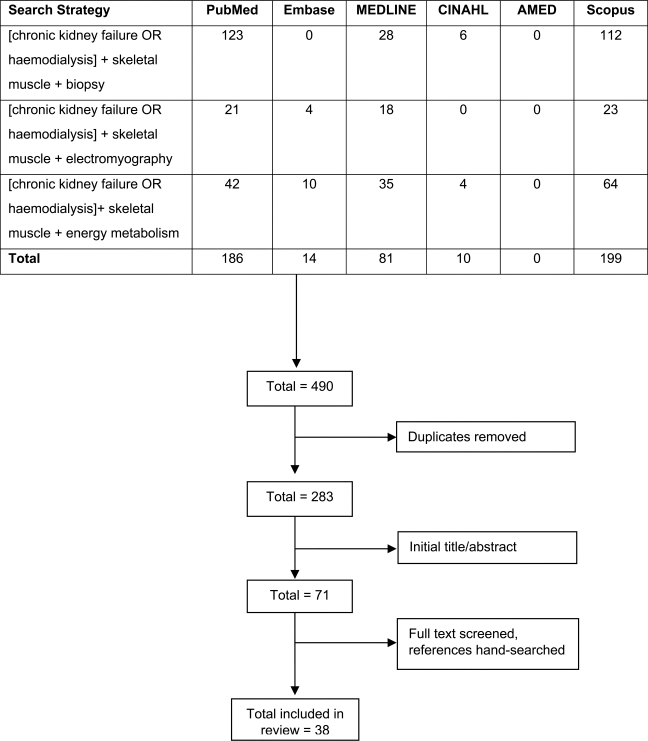

Method: Electronic databases were searched for relevant literature from inception to March 2010. Inclusion criteria were English language; adult subjects with ESRD/HD; and the use of muscle biopsy, electromyography, and nuclear magnetic spectroscopy (31P-NMRS) techniques to evaluate muscle characteristics.

Results: In total, 38 studies were included. All studies of morphological characteristics reported type II fibre atrophy. Electrophysiological characteristics included both neuropathic and myopathic skeletal muscle changes. Studies of metabolic characteristics revealed higher cytosolic inorganic phosphate levels and reduced effective muscle mass.

Conclusion: The results indicate an array of changes in the morphological, electrophysiological, and metabolic characteristics of skeletal muscle structure in people with ESRD/HD that may lead to muscle weakness.

Key Words: electromyography, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), metabolism, muscle weakness, skeletal muscle

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : La fatigue est l'un des symptômes débilitants signalés chez les personnes aux prises avec une insuffisance rénale chronique au stade ultime avec l'hémodialyse (IRSU/HD). Un large éventail d'anomalies sous-jacentes, y compris de la faiblesse du muscle squelettique, ont été mises en cause dans cette fatigue. La faiblesse du muscle squelettique est courante au sein de cette population; une telle faiblesse musculaire peut faire l'objet de traitements en physiothérapie. L'objectif de cette analyse était d'identifier les caractéristiques morphologiques, électrophysiologiques et métaboliques des muscles squelettiques qui pourraient susciter une faiblesse du muscle squelettique chez les personnes avec IRSU/HD.

Méthode : Une recherche a été réalisée dans les bases de données électroniques de leur création à mars 2010 afin de répertorier la documentation pertinente. Les critères d'inclusion étaient que ces documents soient en anglais, qu'ils concernent des adultes avec IRSU/HD et que des techniques de biopsie musculaire, d'électromyographie et de spectroscopie magnétique nucléaire (31P-NMRS) avaient été utilisées pour évaluer les caractéristiques des muscles concernés.

Résultats : Au total, 38 documents ont été répertoriés et utilisés. Toutes les études des caractéristiques morphologiques faisaient état d'atrophie des fibres de type II. Les caractéristiques électrophysiologiques incluaient à la fois les changements névropathiques et myopathiques. Les études des caractéristiques métaboliques ont révélé des niveaux de phosphate inorganique cytosolique plus élevés et ont réduit la masse musculaire effective.

Conclusion : Les résultats font état d'une gamme de changements dans les caractéristiques morphologiques, électrophysiologiques et métaboliques de la structure du muscle squelettique chez les personnes avec IRSU/HD susceptibles de provoquer une faiblesse musculaire.

Mots clés : électromyographie, faiblesse musculaire, insuffisance rénale chronique au stade ultime (IRSU), métabolisme, muscle squelettique

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of chronic renal disease, defined as progressive loss of renal function over a period of months or years, has increased in the last decade. According to a report published by the Canadian Organ Replacement Register (CORR), the rate of incident renal replacement therapy has increased by 19% in Canada since 1999.1 At the end of 2008, more than 36,638 Canadians registered with CORR (an increase of 57% since 1999) were either on renal replacement therapy (21,754) or living with a kidney transplant (14,884).1 Renal disease affects multiple organ systems, resulting in a constellation of symptoms related to anaemia, impaired cardiac function, changes in skeletal muscle strength, and reduced aerobic capacity.2 In the end stages of renal disease (ESRD), renal replacement therapies such as haemodialysis (HD), peritoneal dialysis (PD), or kidney transplant are required to prevent death. A successful kidney transplant provides a better quality of life because it allows greater freedom and is often associated with increased energy levels and a less restricted diet.3

Haemodialysis is considered to have more pronounced deleterious effects on skeletal muscle than PD.4 The two types of dialysis differ in both technique and function. One difference is fluctuation in toxin levels: people on PD dialyze every four hours or daily, whereas HD is typically conducted three times per week, and toxin levels therefore range from very low immediately after dialysis to very high before dialysis.4 The permeability of the dialyzer used for HD may also contribute to the catabolic effect on muscle mass.5 This review focuses only on people with chronic ESRD receiving HD.

Fatigue is one of the most common debilitating symptoms reported by people with ESRD/HD: the prevalence of fatigue in this population ranges from 60% to 97%.6 Various factors—including (a) physiological (decreased aerobic capacity and muscle strength); (b) psychological and behavioural (anxiety, stress, depression, sleep disorders); (c) dialysis-related (dialysis-related fatigue, frequency of dialysis, associated changes in lifestyle leading to physical limitations); and (d) socio-demographic (employment status, social support)—have been implicated as causative mechanisms associated with this fatigue.6 Some of these underlying mechanisms of fatigue, such as skeletal muscle weakness, can be treated by physiotherapists working regularly with this population.7–9

Several reviews have confirmed the presence of muscle weakness and reduced physical function in this population.2,10–12 A similar report of reductions in physical function in a Canadian ESRD/HD sample was reported by Overend et al.;13 mean scores of the physical function measures were in the tenth percentile of established normative values for community-dwelling residents between 65 and 85 years of age.14

Observations of progressive proximal muscle weakness in people with ESRD/HD by Floyd et al.,15 Lazaro and Kirshner,16 and others were ascribed to myopathy (skeletal muscle damage). However, other factors related to ESRD/HD, such as sensorimotor neuropathy from uremia and defects of the neuromuscular junction, have also been considered as possible causes of muscle weakness in people with ESRD/HD.17 Myopathy is characterized by structural changes in skeletal muscle that modify its morphological features and its electrophysiological and metabolic responses to exercise. For example, accumulation of metabolic by-products such as inorganic phosphate (Pi) inhibits force generation in the first dorsal interosseous muscle of both healthy people and those with myophosphorylase deficiency.18 Knowledge of underlying mechanisms underpins the rationale of safe exercise administration;19 this may be particularly important in people with ESRD/HD who have documented evidence of muscle weakness and progressive deterioration of strength. For example, exercise administration in people with neurological disorders is targeted at improving neural plasticity20 and strength,21 whereas for people with myopathic disorders, exercise interventions require careful monitoring to avoid muscle damage.22 According to Phillips and Mastaglia,23 further research is required to determine optimum training protocols for people with various types of myopathies. There is no current review of changes intrinsic to skeletal muscle at rest or during activity in people with ESRD/HD. The aim of our review, therefore, was to identify the underlying morphological, electrophysiological, and metabolic changes in skeletal muscle that may cause skeletal muscle weakness in people with ESRD/HD and to discuss the clinical relevance of these findings.

METHODS

Literature Search

Electronic databases (AMED, CINAHL, EMBASE, Medline, PubMed, and SCOPUS) were searched from their inception until March 2010, using different strategies reflecting the heterogeneity of the causes of skeletal muscle weakness and/or endurance. The following keywords were searched as MeSH or “mapped terms” and as text-words:

[Chronic kidney failure OR chronic renal failure OR haemodialysis] AND skeletal muscle AND biopsy

[Chronic kidney failure OR chronic renal failure OR haemodialysis] AND skeletal muscle AND electromyography

[Chronic kidney failure OR chronic renal failure OR haemodialysis] AND skeletal muscle AND energy metabolism

Reference lists in retrieved articles were hand-searched to identify citations not captured by the primary search strategy.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) paper was published in English; (b) study participants were adults (>18 years of age) receiving haemodialysis; and (c) studies used skeletal muscle biopsy, electromyography (EMG), or magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-NMRS) as tools to identify structural, electrophysiological, and metabolic changes in skeletal muscle (these tools have been identified for evaluation of changes associated with muscle damage17).

Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were the following: (a) ESRD was a complication of an underlying disease mechanism other than renal disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus or Wegener's disease; (b) study participants received haemodialysis following acute renal failure (the aim of our review was to identify changes in skeletal muscle as a sequel to maintenance haemodialysis for ESRD); (c) the paper described an animal study; or (d) energy metabolism was studied using techniques other than 31P-NMRS.

Methodological Quality

To identify the relationship between muscle weakness and changes in skeletal muscle, case-control studies in which people with ESRD were compared to people without the disease were considered appropriate.24 Internal and external validity were assessed according to criteria recommended by Elwood for critical appraisal of case-control studies.24 As statistical criteria, sample size, and power need to be considered for establishing possible type I or type II errors, these were included in the critical appraisal. Case series were also included in this review, as case-control studies have been considered a progression of case series.24 However, case-series studies were not critically appraised, since a case study or case series, by definition, consists of a description of one or several people with the outcome of interest and documents one or more unusual conditions.25

RESULTS

The primary search retrieved a total of 490 citations. After removal of duplicates, the remaining citations were subjected to sequential title, abstract, and full-text screens for final inclusion in the review. The reference sections of articles that met the inclusion criteria were hand-searched for citations missed during the electronic searches. Finally, 38 studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in the study (see Figure 1). All studies included in this review were either case-control (cross-sectional) studies (n=26) or case series (including one single case report) (n=12).

Figure 1.

Search and selection process for included studies

Methodological Quality

Description of the participants obtained from 10 case-control studies26–35 provided adequate evidence of equal opportunity of inclusion in the study to demonstrate absence of selection bias. Of the remaining case-control studies, seven15,36–41 included participants with chronic renal disease not on HD and with comorbidities (clinical evidence of polyneuropathy, varying degrees of paresis, myopathy, renal bone disease, cerebrovascular accident, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, etc.); four included male participants only;42–45 and five46–50 did not provide adequate description of the participants included in the study. Inclusion of participants with clinical evidence of neuromuscular involvement, wide age ranges, and comorbidities that could contribute to neuromuscular impairment suggested possible selection bias that could confound the outcomes of these studies.24

None of the studies blinded outcome assessors, a protocol that has been recommended for credibility of study results of muscle biopsy.51 Although the outcomes included for this review appear to be objective measures, interpretation of outcomes such as interference patterns obtained during EMG52 and interpretation of skeletal muscle biopsy with prior knowledge of diagnosis have been considered subjective.51 In order to minimize potential subjectivity associated with lack of blinding to participant diagnosis, however, computerized detection and quantification of outcomes in accordance with standardized criteria were employed in studies using muscle biopsy and EMG. None of the studies reported power analyses or sample-size calculations justifying an adequate number of participants to guard against type II error, although studies that demonstrated statistical significance had sufficient power, by convention, to protect against type I error.

Muscle Biopsy Studies

Table 1 summarizes the data from the 16 studies that used muscle biopsy as a tool to evaluate morphological characteristics of skeletal muscle in people with ESRD/HD. Atrophy of type II fibres was a common finding in all studies. Five studies9,27,34,37,53 objectively measured muscle strength using laboratory measures such as isokinetic muscle dynamometry,27 maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) with strain gauge/dynamometry,9,34,37,53 or functional strength measures.37 Two of these studies27,37 reported statistically significant reductions in muscle strength in all participants with ESRD/HD. Of these, one27 suggested an association of muscle weakness with mixed (neuropathic and myopathic) changes; the biopsy findings from the second study37 were comparable between participants with ESRD/HD and control subjects. The remaining three studies9,34,53 reported lower or reduced values of muscle strength in people on HD. One of these studies9 suggested that muscle weakness was associated with mixed (neuropathic and myopathic) changes. Giovenali et al.53 observed atrophy of Type I and II fibres (changes similar to those following myopathy and/or disuse atrophy54) but did not attribute these to myopathic or neuropathic changes, as their primary objective was to evaluate changes in muscle morphometry following L-carnitine intervention. Biopsy findings from the final study34 were comparable between participants with ESRD/HD and controls. All five studies investigated the same muscle (quadriceps), so the variation in results may reflect the differences in the techniques used to analyze the biopsy results or the influence of ESRD/HD on different components of the motor-unit complex, as suggested by Griggs et al.17

Table 1.

Muscle Biopsy Studies in People with End-Stage Kidney Disease on Haemodialysis

| Author (Date) | Study Design | Muscle; Biopsy Type | Measure of Muscle Strength | Sample (n) | Results |

Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I Fibres | Type II Fibres | Other Microscopic Changes | ||||||

| Adeniyi (2004)55 | Single case report | Quadriceps; type of biopsy not indicated | Clinical assessment of muscle strength (measures not reported); report of difficulty rising from the chair | HD=1 | Scattered atrophic fibres | Scattered atrophic fibres | Type I and II fibres equally involved, consistent with neuropathic myopathy | Reports do not support myopathy as a primary cause of weakness. |

| Ahonen (1980)36 | Case-control | Gastrocnemius (medial head); open muscle biopsy | Implicit suggestions of muscle weakness based on prior published reports of myopathy in people with ESRD/HD | HD=11 Con=9 |

Diameter of type I fibres slightly larger than reference group (type I hypertrophy) (p>0.01) |

|

|

|

| Bautista (1983)56 | Case series | Deltoid; method of biopsy not indicated | Clinical evaluation demonstrated proximal muscle weakness (measures not reported) | HD=10 |

|

|

|

Myofibrillar changes suggestive of myopathic factors contributing to muscular weakness |

| Crowe (2007)26 | Case-control | Quadriceps femoris (lateral); percutaneous needle biopsy | Implicit suggestions of muscle weakness based on prior published reports of limited exercise capacity contributing to poor quality of life | HD=10 Con=10 |

Fibre diameter reduced by 15% (p=0.04) | Fibre diameter reduced by 20% (p=0.03) | No difference in proportion of type I and II fibres compared to Con (p=0.9) |

|

| Diesel (1993)27 | Case-control | Vastus lateralis; open muscle biopsy |

|

HD=8 Athl=7 Con=5 |

Hypertrophy of type I fibres (n=2) |

|

|

|

| Fahal (1997)37 | Case-control | Quadriceps femoris (lateral); percutaneous conchotome biopsy |

|

HD=12 Con=10 |

|

|

|

|

| Floyd (1974)15 | Case-control | Quadriceps or biceps; open muscle biopsy | Clinical assessment of strength (measures not reported) | HD=10 Non- dialyzed=4 |

Variation in muscle fibre size was outside normal limits in the majority of the cases | Type II fibre atrophy in each case |

|

Results support myopathic changes associated with renal failure as possible cause of muscular weakness. |

| Giovenali (1994)53 | Case series | Vastus lateralis; open muscle biopsy |

|

HD=26 | Atrophy of type I fibres | Atrophy of type II fibres | N/A | The main objective of the study was to assess the effect of L-carnitine on muscle strength. The baseline data were included. |

| Kouidi (1998)9 | Case series | Vastus lateralis; open muscle biopsy | MVC using dynamometer | HD=7 | Changes in HD:

|

|

|

|

| Lazaro (1980)16 | Case series | Quadriceps femoris; open muscle biopsy | Clinical assessment of strength (measures not reported), participant reports of gait abnormalities such as waddling gait or difficulty walking, difficulty rising from chair | HD=4 | No comment on changes in type I fibres |

|

|

|

| Moore (1993)57 | Case series | Rectus femoris; percutaneous needle biopsy | Implicit suggestions of muscle weakness based on prior published reports of uremic myopathy | HD=11 | Numerous atrophic type I fibres | Numerous atrophic type II fibres | Variability in type I and type II fibres was large | Peripheral factors contributing to skeletal muscle weakness |

| Molsted (2007)31 | Case-control | Vastus lateralis; open muscle biopsy |

|

HD=14 Con=12 |

Several patients on HD had <15% type I fibres p<0.001 | More of type IIx fibres | N/A |

|

| Sakkas (2003)58 | Case series | Medial head of gastrocnemius; percutaneous muscle biopsy using conchotome technique | Implicit suggestions of muscle weakness based on prior published reports of reduced exercise capacity in people on HD | HD=12 | Dominance of type I fibres | Type IIa fibres dominant in the distribution of type II fibres | Proportion of fibres with central nuclei within the normal range |

|

| Sakkas (2004)4 | Case series | Medial head of gastrocnemius; percutaneous muscle biopsy using conchotome technique | Implicit suggestions of muscle weakness based on prior published reports of uremic myopathy | HD=12 | No data | No significant difference between mean CSA of type IIa and IIx fibres | No data |

|

| Shah (1983)49 | Case-control | Quadriceps; method of biopsy not indicated | Complaints of proximal muscle weakness in all participants | HD=10 Con=8 |

Atrophy of type I fibres | Preferential atrophy of type II fibres | Abundant lipid droplets in type I and II fibres |

|

| van den Ham (2007)34 | Case-control | Vastus lateralis; needle biopsy techniques | MVC using dynamometry HD=Reduced MVC |

HD=14 Con=18 |

Similar to that of Con group | Similar to Con group | N/A | Physical inactivity in people on HD contributes to muscle weakness. |

Athl=athletes; CAPD=continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; Con=control group; CSA=cross-sectional area; HD=haemodialysis; MVC=maximim voluntary contraction; N/A=not applicable

Five studies15,16,49,55,56 reported the presence of muscle weakness based on clinical assessment or subjective reports of muscle weakness in the participants on HD. Based on the pattern of atrophy observed, two studies16,55 suggested neuropathic changes preceding myopathic changes; in the remaining three studies,15,49,56 myopathic changes were observed.

Six studies4,26,31,36,57,58 suggested, based on previous literature, that muscle weakness exists in people with ESRD/HD. Five of these studies4,26,31,57,58 observed myopathic changes on biopsy, and the remaining study36 observed myopathic changes in three participants, neuropathic changes in seven participants, and mixed neuropathic and myopathic changes in one participant.

A review of changes detectable via electron microscopy was beyond the scope of this review. However, findings of streaming and degenerating Z-bands in two studies9,27 on electron microscopy by two studies included in this review were considered notable, as these changes indicate muscle damage.

Electrophysiological Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the findings of the 15 studies that assessed electrophysiological associations of muscle weakness with varying electrophysiological protocols using surface or needle electrodes. Various electrophysiological techniques—(1) motor-unit recruitment pattern or interference pattern; (2) compound muscle action potential (CMAP), a measure of summed electrical activity in the muscle; (3) total muscle power analysis using computer techniques; and (4) single-fibre EMG—were used to detect motor-unit characteristics in the studies included in this review.

Table 2.

Electrophysiological Studies of People with End-Stage Renal Disease on Haemodialysis

| Author (Date) | Study Design | Muscle; Type of Investigation | Measure of Muscle Strength | Sample (n) | Results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeniyi (2004)55 | Single case report | Iliopsoas, quadriceps, and TA; EMG recordings (type of electrode used not clearly indicated) | Clinical assessment of muscle strength (measures not reported); participant report of difficulty rising from chair | HD=1 | Brief, small, abundant polyphasic potentials characteristic of myopathy | EMG studies suggestive of neuropathic and myopathic changes |

| Albertazzi (1980)46 | Case-control |

|

Unclear | HD=20 Con=20 |

|

Results support myopathy as a possible cause of muscular weakness. |

| Bautista (1983)56 | Case series | Deltoid; type of electrodes used not indicated | Clinical evaluation demonstrated proximal muscle weakness (measures not reported) | HD=8 | Normal interference pattern | Normal EMG changes |

| Blank (1986)61 | Case series | BB; EMG using needle electrode | Implicit suggestions of muscle weakness based on prior published reports of common complaints of muscle weakness in people on haemodialysis | HD=9 |

|

Observations suggest neuropathic origin in 4 participants and myopathic origin in 5 participants. |

| Fahal (1997)37 | Case-control |

|

|

HD=19 Con=27 |

|

|

| Floyd (1974)15 | Case-control | Quadriceps and deltoid; EMG recordings using needle electrode | Clinical assessment of strength (measures not reported) | HD=10 Con=7 |

|

Results suggest skeletal muscle weakness of neuropathic and myopathic origin. |

| Gambaro (1987)29 | Case-control | ABD and EDB (authors have not clearly indicated the muscles explored); EMG using needle electrode to study motor unit action potential following stimulation of ulnar and CPN | Symptoms of peripheral nervous system involvement, including muscle weakness, present in 55% of participants on HD (measures not reported) | HD=31 Con=30 |

|

|

| Harrison (2006)59 | Case series | 1st dorsal interrosseous and vastus lateralis; EMG recordings using surface electrode | 30-second chair-stand test (12±0.8); no comparison with Con | HD=25 | EMG frequency recorded prior to HD was generally low and abnormal. |

|

| Isaacs (1969)63 | Case series |

|

Participant complaints of muscle weakness by the participants on HD associated with functional limitations (measures not reported) | HD=15 |

|

|

| Johansen (2005)38 | Case-control | TA; CMAP before and after exercise protocol; start @ 10% MVC and ↑ 10% every 2 min. End-of-exercise MVC and CMAP obtained | MVC using dynamometry (p=0.04) | HD=33 Con=12 |

CMAP was lower at baseline and did not change significantly after the exercise (p=0.003). |

|

| Konishi (1981)30 | Case-control | EDC; SFEMG using needle electrode to obtain fibre-density and jitter values | Implicit suggestions of muscle weakness based on presence of peripheral neuropathy in people on HD as per prior published reports | HD=19 Con=20 |

|

|

| Lazaro (1980)16 | Case series | Variable proximal muscles | Clinical assessment of strength (measures not reported), participant reports of gait abnormalities such as waddling gait or difficulty walking, difficulty rising from the chair | HD=4 | Bizarre high-frequency discharges in one participant; all participants demonstrated short-amplitude and short-duration polyphasic potentials in all muscles examined. | Changes attributed to uremic myopathy |

| Rochhi (1986)48 | Case-control |

|

Possible presence of weakness based on presence of myopathy and neuropathy as per prior published reports | HD=20 Comparison with normal values for the laboratory |

8 HD participants showed significant shift of the peak frequency of the spectral array toward values higher than Con group. |

Results support myopathy as cause of muscle weakness. |

| Sobh (1992)62 | Case series | BB representative of proximal muscle, and APB representative of distal muscle; EMG study including duration of MUAP amplitude, and interference pattern | Possible presence of weakness based on presence of neuropathy as per prior published reports | HD=6 |

|

Results indicate distal involvement and neuropathic pattern. |

| Tilki (2009)25 | Case-control |

|

Possible presence of weakness based on presence of neuropathy as per prior published reports | HD=30 Comparison with normal values for the laboratory |

|

|

APB=abductor pollicis brevis; ABD=abductor digiti minimi; BB=biceps brachii; Con=control group; CPN=common peroneal nerve; CMAP=compound muscle action potential; CRF=chronic renal failure; EDB=extensor digitorum brevis; EDC=extensor digitorum communis; EMG=electromyography; E-C coupling=excitation–contraction coupling; FFT=fast Fourier transform; HD=haemodialysis group; Hz=hertz; MAPD=mean action-potential duration; MAPA=mean action-potential amplitude; MUAP=motor-unit action potential; MVC=maximum voluntary contraction; NCS=nerve-conduction studies; QEMG=quantitative electromyography; SFEMG=single-fibre electromyography; TA=tibialis anterior; UE=upper extremity

Three studies measured muscle strength objectively, using dynamometry and functional measures of strength.37,38,59 Two of these studies37,38 found statistically significant reductions in muscle strength in participants with ESRD/HD. However, Johansen et al.38 suggested neural mechanisms contributing to muscle weakness, while Fahal et al.37 identified causes intrinsic to the muscle. The variation in results may be related to the differences in the electrophysiological techniques used by these studies: Johansen et al.38 used CMAP, whereas Fahal et al.37 used EMG (interferential pattern). The third study,59 a case series, reported the presence of myopathic changes. The functional measures of strength reported in this study implicitly suggested muscle weakness, since the performance of the ESRD/HD group (age 54.5±2.6 years) on the 30-second chair-stand test (12±0.8 reps) was comparable to that of women between 75 and 79 years of age.60

Of the four studies15,16,55,56 that reported muscle weakness based on clinical assessments (measures not reported), two15,55 suggested neuropathic changes preceding myopathic changes, based on the motor-unit recruitment pattern; one case series16 observed myopathic changes; and the final study56 observed EMG changes comparable to those observed in the control group.

Blank et al.61 observed both myopathic and neuropathic changes, one sub-group demonstrating myopathic changes and a second showing neuropathic changes. While no objective measure of participants' muscle strength was reported by Blank et al.,61 association of muscle weakness with these electrophysiological changes is a possibility, as people with ESRD/HD commonly complain of muscle weakness. Neuropathic changes found in one sub-group by Blank et al.61 are supported by three studies30,35,62 that have suggested possible muscle weakness based on the presence of polyneuropathy in people with ESRD/HD and one study63 reporting muscle weakness based on subjective reports of muscle weakness and functional limitations observed in the study participants. The finding of myopathic changes in another sub-group by Blank et al.61 is supported by similar findings in two studies46,48 that did not suggest (implicitly or otherwise) the presence of muscle weakness in their participants.

Energy Metabolism: In Vivo Studies

Table 3 summarizes the findings of the 13 case-control studies that investigated energy metabolism using 31P-NMRS at rest and during sub-maximal exercise protocols at varying intensities. All studies that used sub-maximal exercise protocols reported reduced exercise durations in all participants with ESRD/HD. Eight studies33,39–42,44,45,50 reported increased cytosolic inorganic phosphates (Pi) at rest in people with ESRD/HD, while four28,38,43,47 reported similar Pi values for the experimental and control groups. One case-control study32 observed lower Pi values in the ESRD/HD group than in the control group, and another33 did not clearly indicate whether the absolute cytosolic Pi values were lower or higher for the ESRD/HD group.

Table 3.

31P-NMR Spectroscopy Studies of Skeletal Muscle in People with End-Stage Renal Disease on Haemodialysis

| Author (Date) | Study Design | Muscle | Exercise Protocol | Sample (n) | Resting Muscle | End Exercise | Recovery | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durozard (1992)28 | Case-control | Calf— dominant side |

Pedal against 98.1N @ 2 Hz (Isotonic) until exhaustion | HD=6 Con=6 |

pH, PCr, Pi, PCr/Pi, ATP were not statistically different (p-value unavailable) |

|

|

|

| Johansen (2005)38 | Case-control | Dorsiflexors | 10%MVC ↑10%MVC every 2 min to fatigue | HD=18 Con=11 |

At-rest Pi, PCr, Pi/PCr, H2PO4-, and pH similar between the two groups |

|

Delayed recovery of MVC returning to ∼85% of pre-exercise MVC after 10 min of rest; Con group recovered fully within same duration (p=0.006) | Excess fatigue attributed to poor oxidative metabolism and greater accumulation of metabolic by-products in people on HD affecting CAR |

| Kemp (1995)42 | Case-control | FDS | Finger flexion @40/min @ 0.75 kg resist for 5 min,↑by 0.25 kg / 1.25 | HD=6 Con=10 |

|

|

|

Reduced effective muscle mass of FDS by 30% of normal in HD group based on metabolic data |

| Kemp (2004)43 | Case-control | Lateral gastrocnemius | 3–5 min voluntary 0.5 Hz, isometric plantar flexion at 50% MVC and 75% of MVC each, 5 min recovery | HD=23 Con=15 |

pH, PCr/γATP, and Pi/γATP similar in both groups | HD group exerted less force (p=0.04). |

|

|

| Moore (1993)47 | Case-control | FDS |

|

HD=11 Con=9 |

Data presented in the graphs suggest no differences in pH, [PCr]/[PCr+Pi] at rest |

|

|

|

| Nishida (1991)44 | Case-control | Biceps femoris, dominant side |

|

HD=8 Con=6 |

|

|

|

|

| Tàborsky (1993)50 | Case-control | Gastrocnemius | Data collected with muscle at rest | HD=21 Con=24 |

PCr/Pi and PCr/ATP ratios higher than Con group (p<0.01) | Examination at rest only—no data | Examination at rest only—no data | Authors suggest possible effect of the impaired metabolism and uremic myopathy. The increase in resting PCr/Pi levels reflects the subjective complaints of muscle weakness. |

| Thompson (1993)45 | Case-control | FDS | Finger flexion @ 40/min against 0.75 kg resistance for 5 min and then↑by 0.25 kg every 1.25 min | HD=5 Con=6 |

|

|

Duration of exercise significantly shorter in HD group (p=0.006) |

Impaired oxidative ATP synthesis and reduced effective muscle mass |

| Thompson (1994)39 | Case-control | Calf | PF of R ankle 30×/min @ 10% of LBM↑2% of LBM after every 1 min, to fatigue | Uremics+ HD=9 Con =18 |

|

End-exercise pH and [PCR]/[PCr+Pi] similar between two groups |

|

|

| Thompson (1996)32 | Case-control | FDS | Ramp exercise protocol requiring participants to frequency of 0.5 Hz through a ROM of 700 and↑0.13 W/min from 0.50 W until exhaustion | HD=5 Con=8 |

Lower values of Pi/Pcr in the HD group (p<0.05) |

|

|

Metabolic data suggest possible higher percentage/predominance of type II fibres, de-conditioning, or impaired aerobic metabolism. |

| Thompson (1996)40 | Case control | Calf | PF of R ankle 30×/min @ 10% of LBM↑2% of LBM after every 1 min, to fatigue | HD=9 Con=9 |

|

|

|

|

| Thompson (1997)41 | Case-control | Calf | PF of R ankle 30×/min @ 10% of LBM↑2% of LBM after every 1 min, to fatigue | PD+HD=10 Con=33 |

|

|

|

|

| Vaux (2004)33 | Case-control | Calf | PF of R ankle 30×/min @ 10% of LBM↑2% of LBM after every 1 min, to fatigue | HD=13 Comparison with normal lab values for people without the disease as Con |

Decreased mitochondrial capacity | Drop in muscle pH during exercise to below 6.9 mmol.min−1 (p=0.01) | Slow proton efflux, reduced exercise duration, slow metabolic recovery, and low QMAX in HD vs. normal lab values |

|

ADP=adenosine diphosphate; ATP=adenosine triphosphate; CAR=central activation ratio; Con=control group; FDS=flexor digitorum superficialis; HD=haemodialysis group; LBM=lean body mass; MVC=maximum voluntary contraction; PCr=creatine phosphate; PD=peritoneal dialysis; pH=potential hydrogen (concentration of hydrogen ion); Pi=inorganic phosphate; PF=plantarflexion; RCT=randomized controlled trial

Of the four studies that reported similar Pi values for the experimental and control groups,28,38,43,47 one investigated the calf muscle,28 one investigated the dorsiflexors,38 and two43,47 investigated the finger flexors. Specific differences among these four studies could not be clearly identified to establish why the cytosolic Pi was comparable to controls; they investigated the same muscles (calf and finger flexors) as the group of studies reporting increased cytosolic Pi, with the exception of the dorsiflexor muscle.38 Perhaps these findings can be attributed to differences in the techniques used to measure the metabolites at rest, as one study28 reported using “unique” methods of measuring absolute cytosolic Pi.

Four studies40–42,45 suggested “reduced effective muscle mass” based on the rate of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis during incremental sub-maximal exercise. Four studies39–42 investigated QMAX (maximum rate of mitochondrial ATP production) in people with ESRD/HD; values ranged from 44% to 77% of control values, indicating impaired ATP production in this population.

Seven studies28,38,39,42,43,45,47 found resting phosphocreatine (PCr) and ATP concentrations comparable to control-group values, including Johansen et al.,38 who also documented reduced MVC force in people with ESRD/HD. Higher levels of PCr and ATP concentration were noted by three studies.40,41,50 According to Nishida et al.,44 however, muscle weakness may be associated with lower concentrations of resting PCr and ATP values in people with ESRD/HD, since these lowered concentrations are consistent with reduced energy production at rest. Nishida et al.'s44 suggestion is supported by findings of lowered resting PCr and ATP in one other case-control study.32 This variability in resting PCr and ATP concentrations may be explained by differences in measurement techniques used, muscles investigated, and/or characteristics of participants included in these studies.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate an array of changes in the morphological, electrophysiological, and metabolic characteristics of skeletal muscle structure in people with ESRD/HD that, alone or in combination, may lead to muscle weakness. These changes include (1) myopathic, (2) neuropathic, and (3) mixed (neuropathic and myopathic) changes existing independently; (4) initial neuropathic changes leading to myopathic changes; and (5) reduced effective muscle mass. Thus, a single potential mechanism associated with muscle weakness in people with ESRD/HD could not be established, since the studies reviewed here indicated neuropathic and myopathic changes together with morphological and electrophysiological changes related to disuse atrophy. Also, because not all studies measured muscle strength directly, consistent relationships between muscle weakness and changes in morphological and electrophysiological characteristics can only be inferred.

The general observation of type II fibre atrophy in all studies using muscle biopsy suggests the presence of weakness linked to sedentary lifestyle in people with ESRD/HD, since type II fibre atrophy is essentially the result of disuse. According to Henneman's size principle, type II motor units are the last to be recruited in voluntary actions.64 The poor health status of people with ESRD/HD may thus restrict activities that require large force production, necessitating recruitment of type II motor units. The findings of muscle damage observed on electron microscopy by Diesel et al.27 and Kouidi et al.9 are similar to changes observed following muscle damage due to eccentric contraction in people without ESRD/HD.65 These findings may support suggestions of progression of proximal muscle weakness15,16 resulting from ongoing muscle damage associated with eccentric contractions of proximal muscles carrying out their postural stabilization role during antigravity activities such as sitting on a chair, standing, or walking.66

The observed electrophysiological changes and the morphological changes in muscle characteristics are similar; both indicate myopathic, neuropathic, and mixed (neuropathic and myopathic) changes in skeletal muscle. These findings support the suggestion of a possible effect of ESRD/HD on the different components of the muscle motor-unit complex. Interestingly, Bautista et al.56 observed morphological characteristics suggestive of myopathy with no changes in electrophysiological characteristics, which implies that these changes could be present independently of each other. This finding may be attributed to the nature of the tools used and the status of the muscle during the test performed, given that EMG reflects muscle characteristics during activity whereas biopsy provides insight into muscle morphology at rest (Bautista et al.56 did not perform muscle biopsy during exercise). Thus, the difference in these outcomes may be related to measurement methods.

Since the exercises prescribed by physiotherapists for people with neuropathic disorders differ from those for people with myopathic conditions,19 an EMG examination to differentiate between neuropathy and myopathy could be recommended for patients with ESRD/HD in order to guide treatment. For example, people with inflammatory polyneuropathy (e.g., Guillain-Barré syndrome) require careful exercise prescription to include activities that facilitate recruitment of type II fibres (speed or rapid rises and falls in muscle force production).67 In the presence of myopathic conditions such as Duchenne's muscular dystrophy, on the other hand, strength training usually begins at a low percentage of the person's one RM (repetition maximum) and requires monitoring for signs and symptoms of overuse, such as myalgias.22

Kemp et al.42 defined “effective muscle mass” as the product of true muscle mass and metabolic efficiency of exercising muscle fibres, basing their calculations of metabolic efficiency on the initial rate of non-oxidative ATP synthesis during incremental sub-maximal exercise, measured using 31P-NMRS. Observations of exercising muscle metabolism were therefore ascribed to “reduced effective mass,” as muscle atrophy alone could not explain the changes in muscle metabolism during incremental sub-maximal exercise in people with ESRD/HD. These observations of reduced effective muscle mass suggest reduced intrinsic contractile efficiency.68 The findings of increased cytosolic Pi lend further support to the theory of reduced contractile efficiency; according to Cady et al.,18 high concentrations of Pi within the muscle have been shown to inhibit maximal force in skeletal muscle. However, using isometric exercise at intensities of 50% and 75% of MVC, Kemp et al.43 showed normal contractile efficiency (measured as force per unit cross-sectional area per unit ATP turnover) of the calf muscle in people with ESRD/HD, and suggested that the reduced oxidative contribution during exercise was due to mitochondrial defects measurable during recovery. The above findings relating to contractile efficiency of skeletal muscle require further exploration, using exercises with various combinations of metabolic demands to establish contractile efficiency of the muscles. Whether such reduced effective muscle mass is also associated with changes in electrophysiological parameters also requires further study; muscle atrophy alone could not account for the lack of correlation between compound muscle action potential (CMAP) and the anterior tibial muscle cross-sectional area observed by Johansen et al.38

In their study, Johansen et al.38 used EMG and spectroscopy techniques suggested by Kent-Braun et al.69 to provide a thorough understanding of electrophysiological and metabolic characteristics during exercise. They suggested that changes in EMG (expressed as central activation ratio) could be associated with poor oxidative metabolism and greater accumulation of metabolic byproducts. The metabolic changes observed in people with ESRD/HD following sub-maximal exercise were comparable to those observed following high-intensity (90% maximal) isometric exercise in people without the disease,28 which suggests a significant reduction in exercise capacity, changes in the EMG, and high energy demands during activities requiring sub-maximal effort, such as activities of daily living. The high energy demands of sub-maximal activity and reduced effective muscle mass provide a rationale for the difficulty with activities of daily living experienced by people with ESRD/HD and, as such, may be an important cause of their functional limitation.

Implications for Physiotherapy

Exercise interventions to address skeletal muscle weakness are important, as people with ESRD/HD have identified management of complications related to dialysis, including fatigue, as the second-highest priority for research.70 The range of changes in the morphological, electrophysiological, and metabolic characteristics associated with muscle weakness in people with ESRD/HD suggest that interventions at an early stage to strengthen the weakened muscles may be beneficial. Kouidi et al.9 were able to demonstrate muscle-fibre hypertrophy and an increase in proportion of type II fibres following six months of exercise (including low-weight resistance training) in this population. Johansen et al.38 did not observe any change in the CMAP (an electrophysiological characteristic of skeletal muscle) following a single bout of exercise. The question of whether a prolonged exercise intervention leads to any changes in electrophysiological and metabolic characteristics requires further investigation.

Sub-maximal isometric contractions in the shortened positions of the muscle are known to be more effective than dynamic training in maintaining type II fibres.71,72 However, this strengthening option has yet to be adequately explored as an intervention strategy in people with ESRD. Although progressive muscle weakness resulting from eccentric muscle contractions has been implicated, research on eccentric muscle damage indicates that practice with eccentric contractions may provide a protective effect for future eccentric contractions. However, the effect of eccentric contractions in muscle demonstrating myopathic changes has not been adequately explored.

The metabolic impairments observed at rest that are suggestive of reduced effective muscle mass or of an anaerobic metabolism may require considerations for appropriate prescription of specific exercise, such as resistance training at lower intensities, for optimal benefits. Several studies have implicated proximal muscle weakness as one of the clinical symptoms of myopathy in people with ESRD/HD. Other studies, however, have demonstrated involvement of the distal muscles as well. This variability in findings is consistent with McElroy et al.'s73 finding of a variable pattern of muscle weakness in people with ESRD/HD. Physiotherapists working with this patient population should therefore perform a complete strength assessment of both proximal and distal muscles prior to prescribing resistance exercise. The impact of ESRD/HD on multiple organ systems, cardiovascular and nutrition status, and the effect of comorbid conditions should also be assessed to determine an individual's ability and tolerance to participate in resistance exercises.

LIMITATIONS

Only studies published in English were included in our review, and we restricted the review to morphological, electrophysiological, and metabolic characteristics of skeletal muscles. Other factors associated with skeletal muscle weakness, such as malnutrition, comorbidities associated with ESRD, vitamin D abnormalities, and impaired glycolytic metabolism, have not been explored in the current review.

CONCLUSION

We reviewed the current best evidence to identify possible muscle-characteristic causes of muscle weakness in people with ESRD/HD. Our findings suggest that numerous changes in the muscle (myopathic, neuropathic, mixed neuropathic and myopathic, and impaired contractile efficiency) may be associated with muscle weakness in this population. The presence of skeletal muscle weakness indicates a need for physiotherapists to adequately assess skeletal muscle strength when people with ESRD/HD report fatigue. Assessment should be followed by initiation of low-intensity strength training as appropriate to each individual's overall physiological status.

KEY MESSAGES

What Is Already Known On This Topic

Physiotherapists treat people with ESRD/HD. There is a high incidence of fatigue in this population, which results in significant functional limitation. Several factors contribute to fatigue, including skeletal muscle weakness. Skeletal muscle weakness is amenable to exercise, but the actual causes of such weakness in people with ESRD/HD have not been determined.

What This Study Adds

This study reviews the best available evidence to identify the morphological, electrophysiological, and metabolic characteristics of skeletal muscle in people with ESRD/HD. The results indicate muscle changes associated with these characteristics, including myopathic changes, neuropathic changes, changes resulting from disuse, and reduced effective muscle mass. A comprehensive assessment is recommended prior to initiating strength training to address skeletal muscle weakness in this patient population.

Sawant A, Garland SJ, House AA, Overend TJ. Morphological, electrophysiological, and metabolic characteristics of skeletal muscle in people with end-stage renal disease: a critical review. Physiother Can. 2011;preprint. doi:10.3138/ptc.2010-18

REFEERENCES

- 1.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Treatment of end-stage organ failure in Canada, 1999 to 2008—CORR 2010 annual report. Ottawa: The Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansen KL. Exercise in the end-stage renal disease population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1845–54. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010009. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidney Transplant [homepage on the Internet] Available from: http://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/kidneytransnewlease.cfm.

- 4.Sakkas GK, Ball D, Sargeant AJ, Mercer TH, Koufaki P, Naish PF. Skeletal muscle morphology and capillarization of renal failure patients receiving different dialysis therapies. Clin Sci. 2004;107:617–23. doi: 10.1042/CS20030282. doi: 10.1042/CS20030282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raj DSC, Sun Y, Tzamaloukas AH. Hypercatabolism in dialysis patients. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:589–94. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32830d5bfa. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32830d5bfa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jhamb M, Weisbord SD, Steel JL, Unruh M. Fatigue in patients receiving maintenance dialysis: a review of definitions, measures, and contributing factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:353–65. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.005. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheema B, Abas H, Smith B, O'Sullivan A, Chan M, Patwardhan A, et al. Progressive exercises for anabolism in kidney disease (PEAK): a randomized controlled trial hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1594–601. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121329. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansen KL, Painter PL, Sakkas GK, Gordon P, Doyle J, Shubert T. Effects of resistance exercise training and nandrolone deconate on body composition and muscle function among patients who receive hemodialysis: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2307–14. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010034. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kouidi E, Albani M, Natsis K, Megalopoulos A, Gigis P, Guiba-Tziampiri O, et al. The effects of exercise training on muscle atrophy in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:685–99. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.3.685. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.3.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheema BSB. Tackling the survival issue in end-stage renal disease: time to get physical on haemodialysis [review article] Nephrology. 2008;13:560–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01036.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moinuddin I, Leehey DJ. A comparison of aerobic exercise and resistance training in patients with and without chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15:83–96. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.10.004. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Painter P. Physical functioning in end-stage renal disease patients: update 2005. Hemodial Int. 2005;9:218–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2005.01136.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2005.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overend T, Anderson C, Sawant A, Perryman B, Locking-Cusolito H. Relative and absolute reliability of physical function measures in people with end-stage renal disease. Physiother Can. 2010;62:122–8. doi: 10.3138/physio.62.2.122. doi: 10.3138/physio.62.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Functional fitness normative scores for community-residing older adults, ages 60–94. J Aging Phys Activity. 1999;7:162–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Floyd M, Ayyar DR, Barwick DD, Hudgson P, Weightman D. Myopathy in chronic renal failure. Q J Med. 1974;43:509–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazaro R, Kirshner H. Proximal muscle weakness in uremia. Arch Neurol. 1980;37:555–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1980.00500580051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griggs RC, Mendell JR, Miller RG. Myopathies of systemic disease. In: Griggs RC, Mendell JR, Miller RG, editors. Evaluation and treatment of myopathies. Philadelphia: FA Davis Co.; 1995. pp. 355–85. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cady EB, Jones DA, Lynn J, Newham DJ. Changes in force and intracellular metabolites during fatigue in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1989;418:311–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilodeau M, Yue GH, Enoka RM. Why understand motor unit behavior in human movement? Neurol Rep. 1994;18:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf SL, Blanton S, Baer H, Breshears J, Butler A. Repetitive task practice: a critical review of constraint-induced movement therapy in stroke. Neurologist. 2002;8:325–38. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000031014.85777.76. doi: 10.1097/00127893-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeJong G, Horn SD, Gassaway HJ, Slavin MD, Dijkers MP. Towards taxonomy of rehabilitation interventions: using an inductive approach to examine the “black-box” of rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:678–86. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.033. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wade CK, Forstch J. Exercise and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Phys Ther. 1996;2:20–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philips BA, Mastaglia FL. Exercise therapy in patients with myopathy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2000;13:547–52. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200010000-00007. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elwood JM. Critical appraisal of epidemiological studies and clinical trials. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Hall Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crowe AV, McArdle A, McArdle F, Pattwell DM, Bell GM, Kemp GJ, et al. Markers of oxidative stress in the skeletal muscle of patients on haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1177–83. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl721. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diesel W, Emms M, Knight BK, Noakes TD, Swanepoel CR, Smit RVZ, et al. Morphologic features of the myopathy associated with chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;22:677–84. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durozard D, Pimmel P, Baretto S, Caillette A, Labeeuw M, Baverel G, et al. 31PNMR spectroscopy investigation of muscle metabolism in haemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1993;43:885–92. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.124. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gambaro P, Bottacchi E, Camerlingo M, D'Alessandro G, Nebiolo PE, Aloatti S, et al. Central and peripheral involvement in hemodialysed subjects: neurophysiological and nephrological relationships. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1987;8:31–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02361432. doi: 10.1007/BF02361432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Konishi T, Nishitani H, Motomura S. Single fiber electromyography in chronic renal failure. Muscle Nerve. 1982;5:458–61. doi: 10.1002/mus.880050607. doi: 10.1002/mus.880050607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molsted S, Eidemak I, Sorensen HT, Kristensen JH, Harrison A, Andersen JL. Myosin heavy-chain isoform distribution, fibre-type composition and fibre size in skeletal muscle of patients on haemodialysis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2007;41:539–45. doi: 10.1080/00365590701421330. doi: 10.1080/00365590701421330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson RT, Muirhead N, Marsh GD, Gravelle D, Potwarka JJ, Driedger AA. Effect of anaemia correction on skeletal muscle metabolism in patients with end-stage renal disease: 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment. Nephron. 1996;73:436–41. doi: 10.1159/000189107. doi: 10.1159/000189107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaux EC, Taylor DJ, Altmann P, Rajagopalan B, Graham K, Cooper R, et al. Effects of carnitine supplementation on muscle metabolism by the use of magnetic resonance spectroscopy and near-infrared spectroscopy in end-stage renal disease. Nephron. 2004;97:c41–8. doi: 10.1159/000078399. doi: 10.1159/000078399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Ham ECH, Kooman JP, Schols AMWJ, Nieman FHM, Does JD, Akkermans MA, et al. The functional, metabolic and anabolic responses to exercise training in renal transplant and hemodialysis patients. Transplantation. 2007;83:1059–68. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000259552.55689.fd. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000259552.55689.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tilki HE, Akpolat T, Coskun M, Stalberg E. Clinical and electrophysiological findings in dialysis patients. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2009;19:500–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2007.10.011. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahonen RE. Striated muscle ultrastructure in uremic patients and in renal transplant recipients. Acta Neuropathol. 1980;50:163–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00692869. doi: 10.1007/BF00692869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fahal IH, Bell GM, Bone JM, Edwards RH. Physiological abnormalities of skeletal muscle in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:119–27. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.1.119. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johansen KL, Doyle J, Sakkas GK, Kent-Braun JA. Neural and metabolic mechanisms of excessive muscle fatigue in maintenance haemodialysis patients. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:R805–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00187.2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00187.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson CH, Kemp GJ, Barnes PR, Rajagopalan B, Styles P, Taylor DJ, et al. Uraemic muscle metabolism at rest and during exercise. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9:1600–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson CH, Kemp GJ, Taylor DJ, Radda GK. Bioenergetic effects of erythropoietin in skeletal muscle. Nephron. 1996;74:239–40. doi: 10.1159/000363082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson CH, Irish AB, Kemp GJ, Taylor DJ, Radda GK. The effect of propionyl L-carnitine on skeletal muscle metabolism in renal failure. Clin Nephrol. 1997;47:372–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kemp GJ, Thompson CH, Taylor DJ, Radda GK. ATP production and mechanical work in exercising skeletal muscle: a theoretical analysis applied to 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopic studies of dialyzed uremic patients. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33:601–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kemp GJ, Crowe AV, Anijeet HKI, Gong QY, Bimson WE, Frostick SP, et al. Abnormal mitochondrial function and muscle wasting, but normal contractile efficiency, in haemodialysed patients studied non-invasively in vivo. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:1520–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh189. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishida A, Kubo K, Nihei H. Impaired muscle energy metabolism in uremia as monitored by 31P-NMR. Nippon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 1991;33:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson CH, Kemp GJ, Taylor DJ, Ledingham JG, Radda GK, Rajagopalan B. Effect of chronic uraemia on skeletal muscle metabolism in man. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8:218–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albertazzi A, Spisni C, Del Rosso G, Palmieri PF, Rossini PM. Electromyographic changes induced by oral carnitine treatment in dialysis patients. Proc Clin Dial Transplant Forum. 1980;10:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore GE, Bertocci LA, Painter PL. 31P-magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment of subnormal oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle of renal failure patients. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:420–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI116217. doi: 10.1172/JCI116217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rocchi L, Feola I, Calvani M, D'Iddio S, Alfarone C, Frascarelli M. Effects of carnitine administration in patients with chronic renal failure undergoing periodic dialysis, evaluated by computerized electromyography. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1986;12:707–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shah AJ, Sahgal V, Quintanilla AP, Subramani V, Singh H, Hughes R. Muscles in chronic uremia—a histochemical and morphometric study of human quadriceps muscle biopsies. Clin Neuropathol. 1983;2:83–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taborsky P, Sotornik I, Kaslikova J, Schuck O, Hajek M, Horska A. 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy investigation of skeletal muscle metabolism in uremic patients. Nephron. 1993;65:222–6. doi: 10.1159/000187478. doi: 10.1159/000187478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brooke MH, Engel WK. The histographic analysis of human muscle biopsies with regard to fiber types, 2: diseases of the upper and lower motor neuron. Neurology. 1969;19:378–93. doi: 10.1212/wnl.19.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blum AS, Rutkove SB. The clinical neurophysiology primer. Totowa (NJ): Humana Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giovenali P, Fenocchio D, Montanari G, Cancellotti C, D'Iddio S, Buoncristiani U, et al. Selective trophic effect of L-carnitine in type I and IIa skeletal muscle fibers. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1616–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.460. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dubovitz V, Sewry C. Muscle biopsy: a practical approach. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adeniyi O, Agaba EI, King M, Servilla KS, Massie L, Tzamaloukas AH. Severe proximal myopathy in advanced renal failure: diagnosis and management. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2004;33:385–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bautista J, Gil-Necija E, Castilla J, Chinchon I, Rafel E. Dialysis myopathy: report of 13 cases. Acta Neuropathol. 1983;61:71–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00688389. doi: 10.1007/BF00688389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore GE, Parsons DB, Stray-Gundersen J, Painter PL, Brinker KR, Mitchell JH. Uremic myopathy limits aerobic capacity in haemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;22:277–87. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sakkas GK, Sargeant AJ, Mercer TH, Ball D, Koufaki P, Karatzaferi C, et al. Changes in muscle morphology in dialysis patients after 6 months of aerobic exercise training. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1854–61. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg237. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harrison AP, Nielsen AH, Eidemak I, Molsted S, Bartels EM. The uremic environment and muscle dysfunction in man and rat. Nephron Physiol. 2006;103:33–42. doi: 10.1159/000090221. doi: 10.1159/000090221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bohannon RW. Quantitative testing of muscle strength: issues and practical options for the geriatric population. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2002;18:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blank A, Gonen B, Zilberman S, Magora A. Electrophysiological pattern of development of muscle fatigue in patients undergoing dialysis. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1986;26:489–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sobh MA, el-Tantawy AE, Said E, Atta MG, Refaie A, Nagati M, et al. Effect of treatment of anaemia with erythropoietin on neuromuscular function in patients on long term haemodialysis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1992;26:65–9. doi: 10.3109/00365599209180398. doi: 10.3109/00365599209180398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Isaacs H. Electromyographic study of muscular weakness in chronic renal failure. S Afr Med J. 1969;43:683–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Henneman E. Relation between size of the neuron and their susceptibility to discharge. Science. 1957;126:1345–7. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3287.1345. doi: 10.1126/science.126.3287.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tiidus PM. Skeletal muscle damage and repair. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Edwards RH, Newham DJ, Jones DA, Chapman SJ. Role of mechanical damage in pathogenesis of proximal myopathy in man. Lancet. 1984;1:548–52. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90941-3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)90941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bassile CC. Guillain-Barré syndrome and exercise guidelines. J Neurol Phys Ther. 1996;2:31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thompson CH, Kemp GJ. 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy of skeletal muscle in chronic renal failure. Med Biochem. 1999;1:97–121. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kent-Braun JA, Miller RG, Weiner MW. Human skeletal muscle metabolism in health and disease: utility of magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1995;23:305–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Carter SM, Hall B, Harris DC, Walker RG, et al. Patients' priorities for health research: focus group study of patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3206–14. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn207. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Duchateau J, Hainaut K. Isometric or dynamic training: differential effects on mechanical properties of a human muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1984;56:296–301. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hurst JE, Fitts RH. Hindlimb unloading-induced muscle atrophy and loss of function: protective effect of isometric exercises. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1405–17. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00516.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McElroy A, Silver M, Morrow L, Heafner BK. Proximal and distal muscle weakness in patients receiving haemodialysis for chronic uremia. Phys Ther. 1970;50:1467–81. doi: 10.1093/ptj/50.10.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]