Abstract

The search for new biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and therapeutic monitoring of diseases continues in earnest despite dwindling success at finding novel reliable markers. Some of the current markers in clinical use do not provide optimal sensitivity and specificity, with the prostate cancer antigen (PSA) being one of many such examples. The emergence of proteomic techniques and systems approaches to study disease pathophysiology has rekindled the quest for new biomarkers. In particular the use of protein microarrays has surged as a powerful tool for large scale testing of biological samples. Approximately half the reports on protein microarrays have been published in the last two years especially in the area of biomarker discovery. In this review, we will discuss the application of protein microarray technologies that offer unique opportunities to find novel biomarkers.

Keywords: Autoantibodies, Autoantigens, Antibody array, Biochip, Biomarkers, Microarrays, Protein array, Reverse phase array

1 Introduction

The discovery of novel biomarkers for the early detection of disease, patient stratification, monitoring therapy and disease progression are a major thrust of biomedical research. Biomarkers are surrogate measurements that enable the prediction of a clinical or physiological state. Ideally, they are easy to measure, inexpensive, non-invasive and highly accurate in making their intended predictions. In clinical practice, there are a handful of biomarkers in use today [1, 2]. For example, elevated troponin in serum suggests myocardial infarction [3], increases in some cancer antigen levels, like CA 125 and PSA, are used to detect and monitor ovarian and prostate cancer, respectively [4, 5]. The detection of autoantibodies to antinuclear proteins may reveal patients with autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus [6]. The increasing shift towards personalizing the care of individuals based upon their specific disease has created a greater demand for biomarkers that can both diagnose and stratify patients. Yet, there exist no biomarkers for the majority of diseases and the sensitivity and specificity of many current markers are not ideal. Despite this large demand, the current rate of discovery of validated molecular diagnostic markers is on the decline.

Large scale approaches, such as genomics and proteomics, provide tools that enable asking questions at the global systems level empowering screening methods for discovering biomarkers [7]. Recent advances in proteomic technologies, including both mass spectrometry and protein microarrays, have enabled large-scale screening of proteins in tissues and serum from patients that are applicable for biomarker discovery. Protein microarrays allow for the simultaneous and rapid analysis of thousands of proteins in high-throughput (HT). Microarrays are used for surveying both antigens and antibodies in blood samples and other biological fluids for informative biomarkers. However, significant challenges still remain to develop, validate and apply these technologies effectively to identify biomarkers for clinical use. This article reviews the application of various types of protein microarray technologies in biomarker discovery.

2 Tools for discovering peptide antigens

2.1 Developing antibody based capture arrays

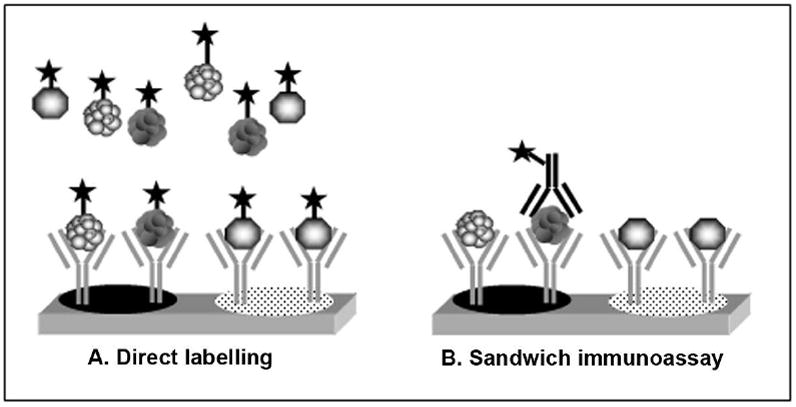

Antibody arrays, for which antibodies are printed onto array surfaces, are designed to capture and measure the relative abundance of their cognate antigens (Fig. 1). They offer the capability to measure levels of multiple analytes in biological samples like serum, plasma, tissue etc., simultaneously. The ability of antibodies to capture and detect analytes with high affinity and selectivity makes these arrays well suited for detecting rare analytes in complex samples.

Figure 1.

Antibody array assay formats. Two assay formats are commonly used (A) Direct labeling – samples are directly chemically modified with fluorescent labels. (B) Sandwich immunoassay – detection of a captured analyte is accomplished with a fluorescently labeled second antibody that binds to a different epitope than the capture antibody. The direct labeling approach depends entirely on the specificity of the capture antibody and is therefore more prone to aberrant signal.

As selective and high affinity reagents, antibodies have found broad applications in solution assays such as western blots, ELISAs, immunohistochemical stains etc. Early use of antibodies in protein microarrays was demonstrated by Haab et al [8]. The authors tested 115 pairs of antibody-antigen interactors in the context of protein arrays. Despite strong evidence that all of these antibodies bound well in solution assays, they found that on the arrays, 60% of printed antibodies could detect their cognate antigens in a pool of all 115 antigens, and only 20% of the antibodies could quantitatively detect differences in the concentrations of the antigen. This study illustrates that although many antibodies work well as solution-based detection reagents, only a fraction of them may work when printed on arrays. This may be due to loss of antibody activity by denaturation during printing or array storage. Alternatively, it might reflect that many antibodies are characterized against denatured protein and thus recognize linear epitopes. When antigens are added to the arrays in solution, the linear epitopes may be buried in the folded protein. Many antibodies that work well on westerns and ELISAs fail to work for immunoprecipitation, for example. Interestingly, when the experiment was inverted, that is, antigen arrays were probed with a pool of antibodies; a much larger number of antibody-antigen pairs were both detected and behaved quantitatively. Finally, as the authors point out, certain antigens may be more labile or sensitive to direct labeling whereas antibodies are more likely to label uniformly. This early work by Haab et al. demonstrated the use of antibody arrays for measuring low concentrations of analyte, and highlights the importance of qualifying antibodies for use with microarrays.

2.2 Detection of antigens in complex lysates

To test whether antibody arrays can be used to detect antigens in complex protein lysates, Sreekumar et al. profiled cancer antigens [9]. The authors used cancer cell lysates from cells that had been treated with and without direct exposure to radiation to probe an antibody array comprising 146 antibodies. The proteins from each treatment were differentially labeled with dual color fluorophores and mixed together. Cross labeling of the lysates was done to avoid the experimental bias due to dye effects. Several antigens were up regulated in radiation-induced cells, namely p53, DFF44 and 45, ICAD as well as TRAIL among others. A majority of the proteins were unchanged while one protein, CEA, was down regulated. This study demonstrated the first use of antibody arrays to monitor changes in levels of antigens in fluorescently labeled complex protein samples. Because the measurements of these candidate antigens relied on the specificity of only a single targeting antibody, the authors confirmed the specificity of their findings using an immunoblot assay.

2.3 Sandwich immunoassay for the detection of cytokines

Several technical issues arise with the use of direct protein labeling, including differential labeling efficiencies and the need to rely solely on the specificity of the printed capture antibody for specificity. To reduce the risk of cross reactivity, Huang et al. used a sandwich assay to measure the levels of 24 cytokines in conditioned media and patient sera [10]. Using antibody pairs that recognize different epitopes on a single antigen, one antibody was immobilized on the array to capture the antigen and the other coupled to HRP for chemiluminescent detection (Fig. 1B). The sensitivity and dynamic range for detecting cytokines by this approach was comparable to or better than that obtained with commercial ELISAs. The improved specificity of a sandwich assay minimizes concerns about aberrant signals from cross reacting signals from single antibodies. However, there exist only a limited set of antibodies that can satisfy the requirements for a sandwich assay: first, the need for two high quality antibodies that recognize different epitopes on the antigen and, second, the absence of cross reactivity between the antibodies and the other antigens being tested in the assay. In the case of cytokines, there are numerous well-established antibody pairs that can be used in sandwich immunoassays; however, for most antigens, compatible antibody pairs with good antigen specificity do not yet exist.

2.4 Application of antibody arrays for cancer biomarker profiling

Most recent studies have focused on the use of antibody arrays to identify cancer related antigens. In a heterogeneous disease like cancer, a single biomarker is not expected to capture the complexity of the disease; rather a panel of antigens is expected to be more informative [11]. Antibody arrays provide sufficient density and throughput for parallel testing of many biological samples for discovering antigens across patient populations.

Serum from patients with cancers of the prostate, lung, pancreas, and bladder were profiled by antibody arrays [12-17; Table 1]. Several antigens were found to be differentially expressed in cancer patients. Miller et al profiled fluorescently labeled prostate cancer sera and identified five proteins that differed in cancer patient sera [12]. In this study, the authors improved their detection limit of the antigens by 6 fold to 200 ng/mL by using a three dimensional acrylamide gel surface as opposed to the traditional chemically derivatized planar surface. Improved sensitivity may reflect a higher binding capacity of the surface or the improved ability to preserve antibody function. Using this chemistry, they observed that the detected antigens were mostly abundant proteins in serum with concentrations in either micrograms or milligrams per milliliter of sera. For antigens like PSA, typically found in the range of nanograms per milliliter, only sera with highly abundant PSA were detected.

Table 1.

Antibody microarrays for biomarker discovery

| Method | Detection Method(s) | Advantages | Limitations | Samples | Results/ Identified markers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Printed on array | Sample Tested | Disease | 1Antigen confirmation | |||||

| Antibody array (antibodies attached to a matrix) | Samples directly labeled with fluorophore |

1 Multiplexed assay 2High throughput |

a Requires an array-compatible capture antibody or affinity reagent b Chemical modification of samples c Poor antibody specificity may lead to signal cross reactivity |

146 antibodies | Cell lysate | Colon cancer | 5 antigens (p53, DFF44 and 45, ICAD, TRAIL) [Ref. 9] | + |

|

| ||||||||

| 184 antibodies | Serum (33 case and 20 control) | Prostate cancer | 5 antigens (von Willebrand Factor, immunoglobulinM, alpha 1-antichymotrypsin, villin and immunoglobulinG) [Ref. 12] | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 378 antibodies | Tissue extract (1 case and control) | Breast cancer | 7 antigens (casein kinase Ie, p53, annexin XI, CDC25C, eIF-4E and MAP kinase 7,14-3-3e) [Ref. 13] | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 224 antibodies | Cell lysate (Doxorubicin-resistant cell line) | Breast cancer | 6 antigens (MAP–activated monophosphotyrosine, cyclin D2, cytokeratin 18, cyclin B1, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein m3 [Ref. 88]) | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Signal amplified using RCA | 1 & 2 apply 3 Improved sensitivity due to signal amplification |

a & c apply | 86 antibodies | Serum (276 cases and 92 controls) | Prostate cancer | 5 antigens differentiate control from benign prostatic disease (anti-thrombospondin-1, -PSA, -gelsolin, -IL-1a and -IGF-1). 1 antigen differentiates benign from malignant prostate (Thrombospondin-1) [Ref. 14] | + | |

|

| ||||||||

| 254 antibodies | Serum (37 cases and 58 controls) | Bladder cancer | 28 antigens (Nephropontin 1, CDC28 protein kinase 2, DNA-dependent protein kinase and procollagen C among others) [Ref. 15] | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 92 antibodies | Serum (92 cases and 50 controls) | Pancreatic cancer | 16 antigens (anti-CRP, -PIVKA-II, -α-1-trypsin, -IgA, -cathepsin D, -alkaline phosphatase, Anti-gelsolin, -TNFa, -MPM2, -IL-6, -IL-8, - transferrin, -troponin, -thioredoxin, - α –2 antiplasmin, -IGF-I) [Ref. 16] | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 84 antibodies | Serum (56 cases and 24 controls) | Lung cancer | 6 antigens (CRP, serum amyloid A, mucin 1, α-1-antitrypsin, transferrin, gelsolin) [Ref. 17] | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Sandwich immunoassay | 1, 2, & 3 apply 4Avoids labeling sample 5Reduced cross reactivity |

d Requires two analyte specific reagents for each target eCross reactivity problematic when multiplexing more than 30 analytes in this format |

24 antibodies | Cell culture supernatant and sera | Glioblastoma | 2 antigens (MCP-1, IL-8) [Ref. 10] | + | |

|

| ||||||||

| 51 antibodies | Cell culture supernatant | Dendritic cells induced by LPS or TNFα | 8 antigens (MIP, IL-8, IP-10, eotaxin-2, I-309, TARC, sTNF-RI, sIL-6R) [Ref. 85] | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 35 antibodies | Cell culture | Breast cancer | 1 antigen (IL-8) [Ref. 89] | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 42 antibodies | Cell culture and Serum (2 cases and 1 control) | Breast cancer | 2 antigens (IL-8 and Growth-related oncogene (GRO)) [Ref. 87] | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Recombinant antibody array | Samples biotinylated with EZ-link SulfoNHS-LC-Biotin | 1, 2, & 3 apply 6Antibodies can be produced in E.coli |

a, b & c apply | 127 antibodies | Stomach tissue (20 cases and 15 controls) | H. pylori infection | 5 antigens (IL-9, IL-11, MCP4, INF-γ, and TGF-β) [Ref. 24] | - |

|

| ||||||||

| 129 antibodies | Serum (20 cases and 20 controls) | Breast cancer | 6 antigens (IL-5, IL-7, IL-8, C3, C4, C5) [Ref. 25] | - | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Reverse phase arrays (Cell/tissue lysates are immobilized) | Staining using a biontinyl-linked peroxidase catalyzed signal amplification | 1, 2, 3 & 4 apply 7Rapid comparison of specific protein levels across many samples under the same condition |

a & c apply fAntigen identification can be challenging |

Cellular lysate | Tissue (40 case) | Prostate cancer | Increased phosphorylation of Akt and decreased phosphorylation of ERK [Ref. 28] | + |

|

| ||||||||

| ” | Tissue (7 case) | Prostate cancer | Activation of AKT, PKC-α, GSK3β, p38; ERK and PKCα in tumor phenotype [Ref. 31] | - | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| ” | 60 human cancer cell lines (NCI-60) | Various cancer | 2 antigens (villin and moesin) [Ref. 43] | + | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| ” | Tissue (40 case) | Ovarian cancer | Higher levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 [Ref. 29] | - | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| ” | Blood lymphocyte (120 normal) | Testing DNA repair capacity | 4 antigens (p27, CCND1, ATM, MDM2) [Ref. 38] | - | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| ” | Cell lines (9) | Bladder cancer | Association of gelsolin to TP53 status during bladder cancer progression [Ref. 86] | + | ||||

Antigen confirmation - if investigators validated hits by other experimental methods e.g. western blot, ELISA, Immunohistochemistry (+ indicates yes, - indicates no).

Validation - Unless otherwise noted, the biomarkers listed here were not validated in an independent sample set of patients and controls

To further improve the sensitivity of the assay, several studies used rolling circle amplification (RCA) to enhance the detection of the antigen [12, 14-17]. Serum from patients with pancreatic cancer and lung cancer were conjugated to either biotin or digoxigenin [16, 17]. Antibodies to these labels were modified with a circular detection DNA template for signal amplification by RCA. This improved the limit of detection of some antigens to as low as 5-30 ng/mL [16]. Using this method several common antigens such as C reactive protein, serum amyloid A and α-1-antitrypsion were found to be significantly different in both cancer sera compared to their respective controls. To ensure the responses were not due to cross reacting signal, the authors confirmed their observations by western blot analysis of the serum.

One challenge of printing antibodies is deciding which analytes to target. An approach used by Sanchez-Carbayois et al. was to target genes overexpressed in cancer [15]. Genes overexpressed in patients with bladder cancer were identified using DNA arrays, and antibodies to those genes were then used to measure the corresponding protein levels in serum. The detected antigens were biased to cell cycle regulation proteins such as p53, cyclin D3, p21 etc and not considered to be specific to bladder cancer.

The potentials of antibody microarrays for molecular profiling of biomarkers were successfully demonstrated by several abovementioned studies; however, sensitivity of the assays and the absence of high quality antibodies (or other analyte specific reagents) for most proteins remain challenges for the success of this technology. Assays that rely on single antibody measurements are often not reliable due to signal cross reactivity and require follow up experiments to eliminate false positives and to confirm the findings. Sandwich assays avoid this problem because of the increased specificity of two antibodies, but the availability of two high quality antibodies for every antigen has been limiting.

2.5 Recombinant antibody microarrays for biomarker profiling

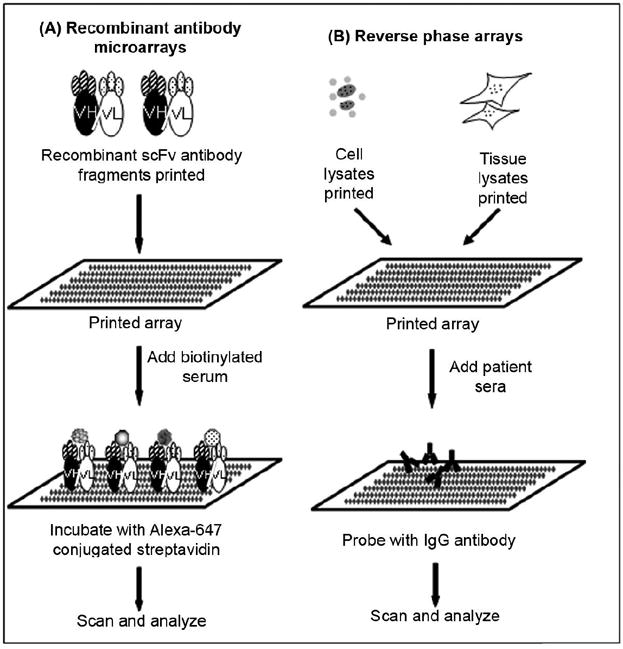

Alternative methods for rapidly producing diverse content of high affinity capture reagents for stably printing on arrays are needed to address the concerns about stability, specificity and diversity of the current antibody collections [18]. An approach developed by Söderlind et al. [19], relied on producing only the single chain variable fragments (scFv) of an antibody that still contained the antigen recognition motif. The resulting product was a fifth in size of a whole antibody, but retained specificity and can be stably produced in E. coli at high levels [19]. The use of recombinant scFv represents a novel twist on the antibody arrays that hold great promise for biomarker discovery. Borrebaeck and colleagues selected human recombinant scFv antibody fragments from a large phage display library for developing recombinant scFv capture arrays [18-20]. To improve the limit of detection for profiling low-abundant protein analytes in nonfractionated samples, the authors selected surface chemistries with improved binding capacity for the scFvs. They also labeled the analyte with biotin allowing the amplification of the signal using fluorescently labeled streptavidin. This approach yielded picomolar sensitivity for the multiplexed analysis of low abundance analytes in complex samples [21-23] (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of recombinant antibody and reverse-phase arrays for biomarker discovery. (A) Recombinant antibody microarrays - recombinant single chain variable-fragment (scFv) antibody fragments selected from a recombinant antibody library and printed on array. Biotinylated serum samples added on array. Array is washed, incubated with Alexa-647 conjugated streptavidin and dried immediately under nitrogen gas. Slides are scanned and analyzed. (B) Reverse-phase array - cell or tissue lysate are printed on arrays. Arrays are incubated with patient’s sera which are then probed with specific antibody to determine relative abundance. Slides are scanned and data analyzed.

A study by Ellmark et al. [24] utilized this approach to generate scFvs from a single framework of recombinant antibody fragments obtained from a phage display library [19]. An array of 127 scFv antibodies was constructed to identify a protein expression signature in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma in the setting of Helicobacter pylori infection. This study showed altered levels of interleukins (IL-2, IL-6, IL-9 etc), INF-α, and TGF-β in tissue infected with H. pylori. The further onset of tumor resulted in the altered abundance of other interleukins (IL-8, IL-4, IL-16 etc) as well as complement proteins (C5, C1a) and monocyte chemotactic proteins (MCP -1, -3, and -4; however, these findings were not further experimentally validated [24]. Another study used a 129 recombinant scFv antibody microarray directed against 60 serum proteins to classify metastatic breast cancer patients and healthy controls, based on differential serum protein profiling [25]. Using a limited number of serum samples (20 healthy controls and 20 breast cancer patients), the authors identified differences in the levels of abundance for 15% of the tested proteins. The changes were mostly observed among several interleukins (IL-5, IL-7, IL-8) and complement proteins (C3, C4, C5). For two antigens (IL-8 and IL-7), the observed changes in abundance between control and disease was observed by two different scFv’s targeting the same antigen adding assurance that the responses reflect changes in the specific target antigen. It is more difficult to explain the cases where multiple scFv’s were available to an antigen but only one showed significant changes in signal. These observations require follow up experiments to eliminate concerns about cross reacting signals. However, these early studies identified several candidate tumor associated inflammatory markers like IL-8, IL-7 as well as complement proteins like C3 and C5 with altered levels in the serum of breast cancer patients and the tissue of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma but not in the tissue of H. pylori infected tissue. These findings require further validation, but they demonstrate the potential for recombinant antibody microarrays in biomarker discovery.

2.6 Reverse phase arrays for biomarker discovery

An alternative approach to protein microarrays, reverse phase arrays (RPAs), immobilizes samples of interest in a manner reminiscent of a dot blot. The array then comprises a variety of samples (e.g. cultured cells, tissue lysates, blood samples, or other), which are then probed with a specific antibody to determine the relative abundance of the targeted antigen in the various samples (Fig. 2B). Detection is accomplished by fluorescent, colorimetric or chemiluminescent [26] and can be amplified by coupling detection antibody with tyramide based avidin/ biotin signal amplification systems [27]. RPA was first introduced by Paweletz et al. [28] where authors printed cell lysates from prostate cancer specimens microdissected to represent tissue cell populations undergoing disease transitions. Results from this study demonstrated that cancer progression was associated with increased phosphorylation of Akt, suppression of apoptosis pathways, as well as decreased phosphorylation of ERK.

A powerful application of reverse phase arrays has been profiling signaling pathways in various cancers, including: ovarian [29, 30], prostate [28, 31] and breast [32, 33]. Using antibodies specific for particular phosphoproteins, RPA can create multiplex readouts of several phosphorylation events simultaneously to profile the state of signaling pathways [26, 34-37]. The abundance of 8 cell-cycle checkpoint-related proteins with DNA repair capacity was assessed in peripheral blood lymphocytes by using RPA [38]. It has also been used to find potential therapeutic agents for malignant glioma [39, 40] and in translational research and biomarker discovery [27, 41].

High throughput molecular profiling of human cancer cell lines (NCI-60) using RPA was performed by Nishizuka et al. [42]. They profiled 60 human cancer cell lines using antibodies to the products of genes that they identified as candidates in previous DNA microarrays experiments [43]. Serial dilutions helped capture the dynamic range. This study identified two pathological markers, villin and moesin, that distinguished colon from ovarian adenocarcinomas.

If antibodies to a protein of interest are available, RPA offers the potential for rapidly comparing the levels of that protein across many samples (cell or tissue) side by side on same array and in the same conditions [27, 42]. The use of RPA presupposes that the researcher has already identified analytes of interest and has access to very high quality antibodies available for use on the arrays. Fundamentally, RPA is a single antibody assay. Thus, identifying antibodies of sufficient specificity requires careful screening for antibody specificity by western blot as well as other methods to ensure there will be no cross-reactivity in reporting signal [44]. Moreover, it is essential to confirm any findings from RPA using traditional assays, such as monitoring changes by western blot. Thus, RPA fits between a pure discovery tool and a validation tool.

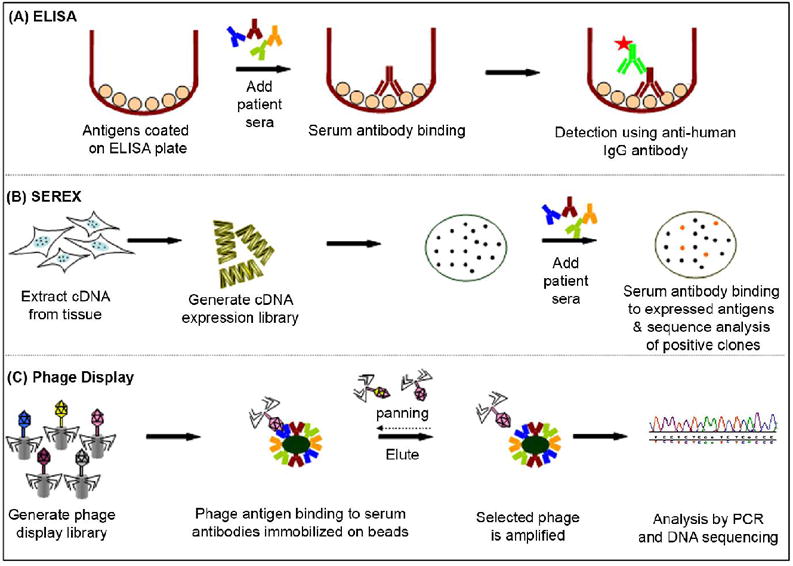

3. Tools for discovering immune responses

Humoral immune responses have been detected in cancer, infectious diseases, autoimmune diseases and other chronic diseases. Standard approaches for detecting humoral immune responses have relied on ELISAs where wells of a 96 well plate are coated with purified antigen (Fig. 3A). Immune responses are measured by detecting the binding of immunoglobulins to the bound antigen using appropriate anti-immunoglobulins. Standard ELISA is easy to adapt and offers a sensitive method for detecting immune responses at low cost. Because ELISA basically studies proteins one at a time, it is too cumbersome and costly to use as a screening tool to discover new antigens.

Figure 3.

Standard tools for discovering immune responses. (A) ELISA – typically wells of microtiter plates are coated with antigen. Patients’ serum samples are incubated in the wells and probed with an enzyme-conjugated anti-human IgG antibody to detect serum response. (B) Serological analysis of recombinant cDNA expression libraries (SEREX) – a cDNA library is typically produced from the tissue- or cell line-based mRNA, expressed by phage in bacteria and then blotted to membranes. Patient’s serum is incubated on arrays and those antibodies that bind to expressed antigens are detected. Positive clones are identified through sequence analysis of phage DNA. (C) Phage display – cDNA expressed and displayed on phage surface. Protein A/G beads are coated with pool of serum IgG antibodies and the phage antigens are incubated with serum antibodies. Adherent phage is eluted and enriched during successive rounds of panning and propagation. Selected phage are analyzed by DNA sequencing.

An early approach used to discover cancer antigens that elicit a humoral response is SEREX technology (serological analysis of recombinant cDNA expression libraries) (Fig. 3B) [45-51]. Phage-based cDNA expression libraries were generated from the relevant cancer tissue and used to produce a large number of tumor antigens in E. coli [47]. The advantage of this approach is that the expression library derives from genes expressed in the tumor, thus producing antigens that are likely to be relevant to the disease. This approach has been successful in discovering over 2,000 antigens relevant to cancer [47, 51]. Most of the antigens discovered to date by SEREX still remain to be validated in controlled studies to determine if the responses are disease specific.

3.1 Validating antigen arrays for detecting serum antibodies

Antigen microarrays have emerged as a versatile tool for HT immune response profiling (Table 2). These arrays allow large number of antigens to be tested across many serum samples simultaneously. Moreover, because replicate arrays can be tested on both patient and control sera, discovery and initial validation can be done in a single step. Some of the earlier work with antigen microarrays focused on validating them for the detection of serum antibodies. Antigen microarrays rely on printing small amounts of antigen onto microscopic features on a planar surface as opposed to coating macroscopic plate wells (Fig. 4A). This raises concerns about the integrity of antigens during printing and storage and whether adequate antigen is presented on the array for sensitive detection. The first test of antigen micorarrays to monitor immune responses was demonstrated by Joos et al [52]. Well known recombinant autoantigens such as Ro and La for Sjorgren’s syndrome, CENP B for Crest syndrome, antinuclear antigens for rheumatoid arthritis and several others were purified either from insect cells, E. coli or tissue and then printed onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The arrays were probed with autoimmune serum containing documented antigenic responses, and the expected selective binding of the serum antibodies to their respective antigens was observed in all cases. To test the sensitivity of detection, the authors performed serial dilution of the serum and established detection limits for serum antibody binding to five autoantigens. In most cases, sensitivities were comparable to standard ELISAs. However in some cases, they noted that sensitivity of the protein spotted arrays was adversely affected upon storage.

Table 2.

Antigen microarrays for biomarker discovery

| Method | Detection Method (s) | Advantages | Limitations | Samples | Results/ Identified markers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Printed on array | Sample Tested | Disease | 1Antigen confirmation | ||||||

| Reverse phase arrays (Cell/tissue lysates are immobilized) | Biotinylated goat-anti-human-Ig followed by phycoerythrin-streptavidin |

1 Raid source of antigens 2 No need for antigen selection 3Disease relevant aberrant gene products 4Availability of PTMs |

a Difficult to identify responding antigen b Samples require complicated fractionation prior to printing |

Complex lysates separated by LC 2D | Serum (25 cases and 25 controls) | Prostate cancer | No antigens identified [Ref. 75] | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| ” | Serum (18 cases and 15 controls) | Lung cancer | No antigens identified [Ref. 76] | - | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| ” | Serum (139 cases and 66 controls) | Prostate cancer | 1 antigen (Kallikrein 11 protein) [Ref. 78] | + | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Reverse capture array | Autoantibodies labeled with CyDyes | 1, 3, & 4 apply 5 Antigens are readily identified |

c Relies on the availability of the capture antibody d Poor antibody specificity may lead to signal cross reactivity |

500 mAb | Serum (10 prostate and 10 BPH cases) | Prostate cancer and BPH | 2 antigens (53BP2 and MUPP1) [Ref. 79] | + | |

|

| |||||||||

| 500 mAb | Serum (10 prostate and 5 BPH cases) | Prostate cancer and BPH | 28 antigens [Ref. 80] | - | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Phage display combined with protein microarrays | Cy3/Cy5-labeled-antibody | 6 Enriches rare disease-specific antigens |

e Majority of the polypeptides are out of frame or truncated gene products f Antigens need to be identified |

Biopanning of phage display library and their lysates arrayed (2304 clones) | Serum (119 cases and 138 controls) | Prostate cancer | 4 antigens, 18 out of frame products (BRD2, eIF4G1, RPL13a, RPL22). An independent validation set (60 case and 68 control) of 22 antigen panel revealed 82% sensitivity and 88% specificity [Ref. 46] | + | |

|

| |||||||||

| 480 clones | Serum (32 cases and 25 controls) | Ovarian cancer | 5 antigens (RCAS1, signal recognition protein-19, AHNAK-related sequence, Nibrin, ribosomal protein L4, casein kinase II) [Ref. 45] | + | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| 4000 clones | Plasma (23 cases and 23 controls) | Lung cancer | 5 antigens (paxillin, SEC15L2, BAC clone RP11-499F19, XRCC5, MALAT1) [Ref. 84] | + | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| High density antigen arrays (Antigens purified and printed – most common method, other methods are also used – Fig. 4) | Anti-IgG Cy3- or Cy5-labelled antibody | 5 applies | h High throughput protein isolation for printing high density arrays remains a challenge | 37200 redundant, recombinant human proteins | Plasma (10 cases and controls) | Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) | 4 antigens (LRPAP1, KCNIP1, PEX13, PHP2) [Ref. 55] | + | |

|

| |||||||||

| 67 human recombinant proteins | Serum (20 cases and controls) | Meningitis | 1 antigen (OpaV) [Ref. 66] | + | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| 82 coronavirus recombinant proteins | Serum (400 cases and controls) | SARS | Constructed coronavirus protein microarrays from six coronavirus proteomes and used them to classify sera from potential SARS infected patients. In a double-blind experiment on 56 serum collected from Chinese patients; classified SARS-infected and uninfected with 98% accuracy, 100% sensitivity, and 95% specificity [Ref. 67] | + | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1741 F. tularensis proteins | Serum (Group of 5-10 immunized and control mice) | Tularemia | 48 antigens (chaperone protein groEL, pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 among others). [Ref. 58] | - | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| 5,005 human proteins | Serum (30 cases and 30 controls) | Ovarian cancer | 94 antigens (Lamin A/C, SSRP1, RALBP1 etc.) [Ref. 83] | + | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| 37200 redundant, recombinant human proteins | Serum (24 case and controls) | Alopecia areata | 8 antigens (cDNA clone GLCDAC05; cDNA FLJ12693 fis, clone NT2RP1000324NOL8; endosulfine; signal recognition particle subunit 14; FGFR3; endemic pemphigus foliaceus autoantigen; dematin; Neuron-specific growth-associated protein) | + | |||||

Antigen confirmation - if investigators validated hits by other experimental methods e.g. western blot, ELISA, Immunohistochemistry (+ indicates yes, - indicates no).

Validation - Unless otherwise noted, the biomarkers listed here were not validated in an independent sample set of patients and controls

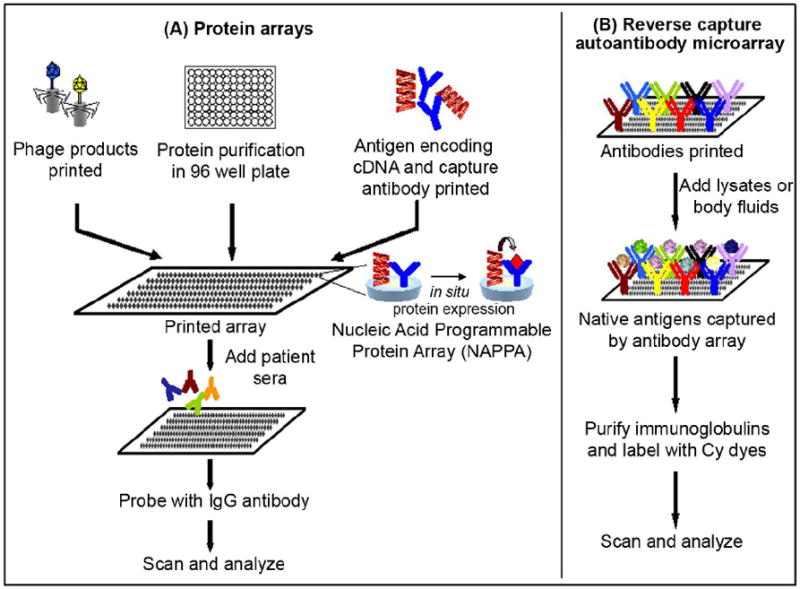

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of various strategies to fabricate protein microarrays for displaying antigens. (A) Purified proteins or phage products are printed on arrays. Alternatively, plasmid DNA encoding full length genes are printed onto an array surface along with a capture antibody. A mammalian cell free expression system such as a T7 coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate is added to simultaneously express all proteins on the array. Protein arrays are incubated with patient’s sera and probed with IgG antibody. (B) In reverse capture autoantibody microarray, well-characterized monoclonal antibodies are printed on an array. Samples (e.g. lysates or body fluids) are incubated and native antigens captured by the antibodies on an array. Immunoglobulins are purified from patient sera and labeled with different cyanine dyes (Cy3 and Cy5), which are then added to the captured antigens on the array. In both cases slides are scanned and data analyzed.

A similar study was performed by Robinson et al. to characterize serum autoimmune responses to known autoantigens from eight autoimmune diseases [53]. In their study, they found the serum antibody binding to the antigen to be selective and observed 4-8 fold higher sensitivity than conventional ELISA. They demonstrated that by using overlapping peptides, immunodominant epitopes can be identified and immune responses can be sub-typed using sub-type specific detection antibodies. These early reports established that the sensitivity and specificity of antigen arrays were adequate for detecting serum antibodies in autoimmune diseases.

3.2 Generating content for high density antigen arrays

There are many diseases for which the immune response is poorly characterized; the discovery of new and informative antigens would benefit if whole proteomes could be analyzed. An early approach was to generate cDNA expression libraries from human tissue such as human fetal brain to create a redundant set of cDNA clones (37,200), which were then expressed in E. coli, and spotted onto large filters without purification. These arrays were then probed either with pooled sera from patients with alopecia areata or with plasma from individual patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) [54-57]. The authors identified 23 antigens which elicited an immune response in two or more pools of patient sera with alopecia areata and 48 antigens in two or more patients with DCM [55]. To confirm the responses, the antigens were purified and printed on a focused array to test individual sera from patients and controls. In the alopecia areata study, 8 of the 23 antigens were confirmed, while 26 of 48 antigens continued to show elevated responses in patients with DCM. No shared immune responses were observed in patients with alopecia areata and DCM.

This approach offers the same advantages as the SEREX technology in using cDNA libraries as a rich source of antigens but combines this with the convenience of printing expressed products for parallel processing. Some potential drawbacks of using cDNA libraries are challenges in expressing rare transcripts, and the presence of out of frame, or truncated gene products. An earlier study estimated that only 6 to 8% of a cDNA library may yield clones that produce polypeptides in the natural reading frame [54].

3.3 Immune profiling pathogen antigens for infectious diseases

The most established method for HT production of antigens relies on expression and purification of recombinant proteins in E. coli. Although not all human proteins express well in E. coli, good success has been observed with pathogenic proteins [58-60]. Rapid methods for identifying immunodominant antigens of infectious agents are important for developing effective vaccines. Current strategies of using live attenuated strains as vaccines can lead to toxic effects caused by the non immunogenic antigens [61]. The challenge has been to identify the rare immunodominant antigens that confer protection within the large pathogen proteome.

Recent efforts to sequence, annotate and clone full length ORFs for several pathogens have been successful and many of these reagents are now publicly available [60, 62-64]. What remains is the development of methods to produce proteins for printing high density protein arrays. Some early work focused on developing sub-proteome arrays or proteomes of smaller pathogens to identify immunodominant antigens [58, 65-69]. A study by Steller et al [66] produced 67 of the 102 phase variable genes in Nisseria meningitidis to test immune responses in sera from 20 patients infected with bacterial meningitis [66]. They found that 70% (47/67) of the tested antigens were immunogenic in at least one patient, responses to nine of the antigens tested were shared by at least three patients and response to an outer membrane protein called OpaV was detected in over 50% of the patients tested. Another study by Zhu et al focused on identifying immune responses in patients from Canada and China who suffered from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) due to infection by the coronavirus [67]. They constructed an array representing 82 proteins from six coronaviruses and tested sera from infected patients and healthy controls. In a small double blinded study using 56 serum samples of patients and controls, they found the coronavirus protein microarray was able to classify the patients with 100% sensitivity and 95% specificity. Again, they observed that antigen microarrays were as sensitive or in some cases more sensitive than commercially available ELISAs for detecting immune response to viral antigens.

Another study used commercially available coupled in vitro transcription and translational (IVTT) E. coli extract to produce pathogen proteins for testing serum antibodies [58, 68-70]. Using genomic DNA, ORFs were amplified by PCR, recombined into an expression vector and expressed using E. coli IVTT. The expressed products were directly printed without purification onto a nitrocellulose membrane. This approach was successfully used to detect protein signal based on an epitope tag for over 190 vaccinia viral proteins and 1,700 proteins from Francisella tularensis [58, 68]. The vaccinia antigens were tested with serum from vaccinated humans and infected mice. Of the commonly recognized antigens, the responses were biased towards membrane proteins which serve as favorable candidates for diagnostics or vaccine development. The F. tularensis antigen array was probed with serum from immunized mice, which revealed 12 already documented antigens and 31 previously unreported candidate antigens [58]. Again, a majority (50%) of the immunodominant responses were biased towards membrane proteins.

Using IVTT extracts to produce proteins from amplified ORFs offers an advantage over conventional in vivo methods in that it is simple, fast, and easy to adapt for HT applications. Surprisingly, these studies show membrane proteins produced by IVTT serve as viable antigens for serum antibody binding. This approach works well for detecting strong responses against pathogen proteins. However, this approach is costly and protein yields are low [71]. Moreover, printing unpurified proteins may affect how much antigen is presented at each feature. A majority (99%) of the printed protein is from the lysate which can compete with the expressed antigen for binding to the array surface [68]. Higher background signals may also be observed from cross reacting serum antibodies to spotted lysate proteins.

3.4 Immune profiling human antigens for autoimmune diseases and cancer

Serum antibody responses to autoantigens or tumor antigens vary significantly in the titer of their response. Moreover, target antigens could be the products of any of the ~23,000 human genes including their various splice forms [72, 73] that are further modified post-translationally with glycosylation, myristoylation, acetylation, etc. [11, 74]. Therefore, discovering new serum antibodies against human proteins requires methods to produce large numbers of proteins in HT and methods for sensitive detection of rare serum antibodies.

One approach is to use reverse phase array technology which entails immobilizing complex protein lysates from biological samples of interest in a manner reminiscent of a dot blot (Fig. 2B). The array is then probed with serum antibodies to discover immune responses. A study by Bouwman et al took lysates from disease-related cell lines and separated the lysate into > 1,700 fractions by 2D liquid chromatography. The fractions were lyophilized, resuspended in printing buffer and printed onto a glass microscope slide [75]. This was done for prostate and lung cancer cell lines to derive a disease specific panel of antigen fractions for discovering serum antibodies [75, 76]. They found 38 fractions that produced higher signals in prostate cancer patients than in controls, and 63 fractions in ovarian cancer sera. The responding antigens within the fractions were not identified in this study.

In a later study by Madoz-Gurpide, the authors highlighted challenges in identifying antigens in fractions [77]. First, the putative antigen could be spread over many fractions due to the separation process, and second, the antigen could be 1of as many as 66 proteins in a given fraction [78]. This was addressed by grouping immunoreactive fractions by the order of elution and patterns of immunoreactivity. They used multiple MS based approaches in follow-up experiments to identify 21 immunoreactive antigens found in 3 fractions or more [78]. One protein in particular, human Kallikrein 11 (hK11), known to be overexpressed in prostate cancer was identified as a putative tumor antigen. The sensitivity (93%) and specificity (68%) of the serum response to hK11 was determined by testing 200 serum samples against a purified protein spotted array.

The reverse phase array approach has several advantages for discovering serum antibodies. First, it provides a rapid source of antigens without the need to generate cDNA expression libraries or rely on the availability of cloned ORFs. Second, it can be extended to tissue from patients that may contain relevant proteins for testing, such as proteins with native or disease-specific PTMs or aberrant gene products. This unbiased approach does not require any information a priori about which antigens to test.

A related method developed by Qin et al, called the reverse capture array, also relied on cellular antigens for testing serum antibodies (Fig. 4B) [79]. To isolate the native antigens from cells, the authors used a commercial antibody array containing 500 antibodies. Cell lysates from prostate cancer cell lines were incubated with the antibody array to allow the appropriate antigens to bind to their cognate target antibodies. As a test of antibody occupancy, in a separate experiment, fluorescently labeled lysate was added to the arrays revealing that most of the antibodies (90%) were bound by labeled protein. To determine if any of the captured antigens were recognized by serum antibodies, serum IgG was purified from pooled sera and directly labeled prior to incubating with the antigen bound array. Two antigens namely, 53BP2 and MUPP1, were found to be elevated in serum response, which was later confirmed by western blot analysis. A following study using individual serum samples as opposed to pooled sera failed to identify MUPP1 as a dominant response and 53BP2 was not tested [80]. In this study, response to MUPP1 was observed only in a small subset of patients but was not considered significant. This raises concerns about pooling sera where strong responses from a single serum may dominate the outcome.

Many interesting antigens occur at low abundance in biological specimens. One technique that attempts to enrich interesting antigens uses recombinant phage display technology [45]. A cDNA expression library derived from a relevant tissue is constructed in phage and expressed in E. coli. The phage products that elicit an immune response are captured by serum IgG bound to beads. The bound phage are eluted, amplified and reselected to continue enrichment of the responding phage (Fig. 3C and 4A).

This approach has been applied to detect serum antibodies from ovarian and prostate cancer patient sera [45, 46]. For the detection of ovarian cancer, a 65 antigen panel showed 55% and 98% sensitivity and specificity, respectively. A 22 antigen panel revealed 82% and 88% sensitivity and specificity, respectively, for the detection of prostate cancer [46]. The phage technology combined with protein microarrays provide a powerful technique that allows rare disease-specific antigens to be enriched and tested across many samples. It is worth noting that the amplification process is finite. Therefore, increasing the rounds of biopanning for further enrichment of phage antigens may select for fast growing antigens as opposed to tight binders, and reduce diversity of the putative antigen pool due to over selection.

Another approach is to express proteins from ORF libraries [64, 81, 82]. A well annotated ORF library will ensure all genes are clonally isolated and fully sequence verified. This minimizes redundancy and provides template for full length genes unlike conventional cDNA libraries. Recent work by Hudson et al used a commercially available human protein array with 5,005 proteins printed in duplicate to test sera from patients with ovarian cancer [83]. The proteins were expressed using sf9 insect cells, purified via a glutathione S transferase (GST) fusion protein, and printed onto a nitrocellulose membrane. They found a somewhat surprisingly large number, 15% (730/5005), of proteins had specific responses to sera from patients and not from the healthy controls. However, the responses were not sufficient to differentiate cancer from healthy individuals. The authors sought to measure the amounts of selected immunogenic antigens in the ovarian tissue and found that Lamin A/C, SSRP1, and RALBP1 showed high levels of staining when compared to non cancerous tissue isolated from the same individual. An advantage of using partially purified protein is that proteins are in a readily addressable format that is not obscured by an overabundance of highly expressed proteins.

4 Concluding remarks

In the recent past, there have been significant improvements in the availability of resources and the development of novel proteomic technologies to enable the discovery of protein biomarkers. Antibody microarrays have been used for profiling biological samples like serum for disease specific peptide antigens. However, most approaches have relied on single antibody measurements which are often not specific enough and have the possibility for cross reacting with other protein species. This approach requires orthogonal tests to confirm the specificity of the signals. The risk of cross reacting signal can be considerably reduced by sandwich assays; however, well-established antibody pairs for most antigens do not exist. There is tremendous need for highly specific antibodies or alternative high affinity capture reagents that can function in the context of a protein microarray.

Antigen microarrays have emerged as a powerful platform for discovering serum antibodies as potential biomarkers. There are large collections of ORF libraries and increasing number of techniques readily available for the production and detection of proteins. Efforts from several groups such as the Early Detection Research Network (EDRN), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) and others have made significant strides toward the systematic collection of biological samples from a variety of diseases for testing. The culmination of these advances has enabled the identification of several candidate serum antigen and antibody markers for several diseases including infectious diseases, autoimmune diseases and cancer. What remains is the clinical validation of these markers to measure their utility as biomarkers.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Shane Miersch and Eugenie Hainsworth for critical reading of this manuscript. Joshua LaBaer and Niroshan Ramachandran acknowledge support from the Early Detection Research Network (EDRN, NCI, Grant 5U01CA117374-02) and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (Grant 17-2007-1045). Financial support to Sanjeeva Srivastava from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- BPH

benign prostatic hyperplasia

- CA 125

cancer antigen 125

- DFF44 and 45

DNA fragmentation factors 40 and 45

- GSK3b

glycogensynthase kinase 3b

- ICAD

inhibitor of caspase-activated deoxyribonuclease

- IL

Interleukin

- KCNIP1

Kv channel interacting protein 1

- LRPAP1

low density lipoprotein-related protein associated protein 1

- MDC

macrophage derived chemokine

- MIP

macrophage inflammatory protein

- PEX13

peroxisome biogenesis factor 13

- PHP2

PAP-2-like protein 2

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

- RALBP1

ral binding protein 1

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SELDI

surface enhanced laser desorption ionization

- SSRP1

structure specific recognition protein 1

- sTNF-RI

soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I

- sIL-6R

soluble interleukin-6 receptor

- TARC

thymus and activation-regulated chemokine

- TRAIL

tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis inducing ligand

References

- 1.Frank R, Hargreaves R. Clinical biomarkers in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:566–580. doi: 10.1038/nrd1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rifai N, Gillette MA, Carr SA. Protein biomarker discovery and validation: the long and uncertain path to clinical utility. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:971–983. doi: 10.1038/nbt1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sommerer C, Giannitsis E, Schwenger V, Zeier M. Cardiac biomarkers in haemodialysis patients: the prognostic value of amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin T. Nephron Clin Pract. 2007;107:c77–81. doi: 10.1159/000108647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sokoll LJ, Chan DW. Prostate-specific antigen. Its discovery and biochemical characteristics. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:253–259. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rustin GJ, Bast RC, Jr, Kelloff GJ, Barrett JC, et al. Use of CA-125 in clinical trial evaluation of new therapeutic drugs for ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3919–3926. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keren DF. Antinuclear antibody testing. Clin Lab Med. 2002;22:447–474. doi: 10.1016/s0272-2712(01)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker M. In biomarkers we trust? Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:297–304. doi: 10.1038/nbt0305-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haab B, Dunham M, Brown P. Protein microarrays for highly parallel detection and quantitation of specific proteins and antibodies in complex solutions. Genome Biol. 2001;2 doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-2-research0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sreekumar A, Nyati MK, Varambally S, Barrette TR, et al. Profiling of cancer cells using protein microarrays: discovery of novel radiation-regulated proteins. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7585–7593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang RP, Huang R, Fan Y, Lin Y. Simultaneous detection of multiple cytokines from conditioned media and patient’s sera by an antibody-based protein array system. Anal Biochem. 2001;294:55–62. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson KS, LaBaer J. The sentinel within: exploiting the immune system for cancer biomarkers. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1123–1133. doi: 10.1021/pr0500814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller JC, Zhou H, Kwekel J, Cavallo R, et al. Antibody microarray profiling of human prostate cancer sera: antibody screening and identification of potential biomarkers. Proteomics. 2003;3:56–63. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200390009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudelist G, Pacher-Zavisin M, Singer CF, Holper T, et al. Use of high-throughput protein array for profiling of differentially expressed proteins in normal and malignant breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;86:281–291. doi: 10.1023/b:brea.0000036901.16346.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shafer MW, Mangold L, Partin AW, Haab BB. Antibody array profiling reveals serum TSP-1 as a marker to distinguish benign from malignant prostatic disease. Prostate. 2007;67:255–267. doi: 10.1002/pros.20514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez-Carbayo M, Socci ND, Lozano JJ, Haab BB, et al. Profiling bladder cancer using targeted antibody arrays. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:93–103. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orchekowski R, Hamelinck D, Li L, Gliwa E, et al. Antibody microarray profiling reveals individual and combined serum proteins associated with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11193–11202. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao WM, Kuick R, Orchekowski RP, Misek DE, et al. Distinctive serum protein profiles involving abundant proteins in lung cancer patients based upon antibody microarray analysis. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wingren C, Ingvarsson J, Lindstedt M, Borrebaeck CA, et al. Recombinant antibody microarrays-a viable option? Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:223. doi: 10.1038/nbt0303-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Söderlind E, Strandberg L, Jirholt P, Kobayashi N, et al. Recombining germline-derived CDR sequences for creating diverse single-framework antibody libraries. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:852–856. doi: 10.1038/78458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borrebaeck CA, Ohlin M. Antibody evolution beyond Nature. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1189–1190. doi: 10.1038/nbt1202-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingvarsson J, Larsson A, Sjöholm AG, Truedsson L, et al. Design of recombinant antibody microarrays for serum protein profiling: targeting of complement proteins. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3527–3536. doi: 10.1021/pr070204f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusnezow W, Banzon V, Schröder C, Schaal R, et al. Antibody microarray-based profiling of complex specimens: systematic evaluation of labeling strategies. Proteomics. 2007;7:1786–1799. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wingren C, Ingvarsson J, Dexlin L, Szul D, et al. Design of recombinant antibody microarrays for complex proteome analysis: choice of sample labeling-tag and solid support. Proteomics. 2007;7:3055–3065. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellmark P, Ingvarsson J, Carlsson A, Lundin BS, et al. Identification of protein expression signatures associated with Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric adenocarcinoma using recombinant antibody microarrays. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1638–1646. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600170-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlsson A, Wingren C, Ingvarsson J, Ellmark P, et al. Serum proteome profiling of metastatic breast cancer using recombinant antibody microarrays. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charboneau L, Tory H, Chen T, Winters M, et al. Utility of reverse phase protein arrays: applications to signalling pathways and human body arrays. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2002;1:305–315. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/1.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calvo KR, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF. Clinical proteomics: from biomarker discovery and cell signaling profiles to individualized personal therapy. Biosci Rep. 2005;25:107–125. doi: 10.1007/s10540-005-2851-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paweletz CP, Charboneau L, Bichsel VE, et al. Reverse phase protein microarrays which capture disease progression show activation of pro-survival pathways at the cancer invasion front. Oncogene. 2001;20:1981–1999. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wulfkuhle JD, Aquino JA, Calvert VS, Fishman DA, et al. Signal pathway profiling of ovarian cancer from human tissue specimens using reverse-phase protein microarrays. Proteomics. 2003;3:2085–2590. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheehan KM, Calvert VS, Kay EW, Lu Y, et al. Use of reverse phase protein microarrays and reference standard development for molecular network analysis of metastatic ovarian carcinoma. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:346–355. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500003-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grubb RL, Calvert VS, Wulkuhle JD, Paweletz CP, et al. Signal pathway profiling of prostate cancer using reverse phase protein arrays. Proteomics. 2003;3:2142–2146. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cowherd SM, Espina VA, Petricoin EF, 3rd, Liotta LA. Proteomic analysis of human breast cancer tissue with laser-capture microdissection and reverse-phase protein microarrays. Clin Breast Cancer. 2004;5:385–392. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2004.n.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akkiprik M, Nicorici D, Cogdell D, Jia YJ, et al. Dissection of signaling pathways in fourteen breast cancer cell lines using reverse-phase protein lysate microarray. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2006;5:543–551. doi: 10.1177/153303460600500601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Speer R, Wulfkuhle JD, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF., 3rd Reverse phase protein microarrays for tissue-based analysis. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2005;7:240–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machida K, Thompson CM, Dierck K, Jablonowski K, et al. High-throughput phosphotyrosine profiling using SH2 domains. Mol Cell. 2007;26:899–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petricoin EF, 3rd, Espina V, Araujo RP, Midura B, et al. Phosphoprotein pathway mapping: Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin activation is negatively associated with childhood rhabdomyosarcoma survival. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3431–3440. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q, Bhola NE, Lui VW, Siwak DR, et al. Antitumor mechanisms of combined gastrin-releasing peptide receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor targeting in head and neck cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1414–1424. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan YH, Hu Z, Li C, Wang LE, et al. In vitro expression levels of cell-cycle checkpoint proteins are associated with cellular DNA repair capacity in peripheral blood lymphocytes: a multivariate analysis. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1560–1567. doi: 10.1021/pr060655k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yokoyama T, Kondo Y, Kondo S. Roles of mTOR and STAT3 in autophagy induced by telomere 3’ overhang-specific DNA oligonucleotides. Autophagy. 2007;3:496–498. doi: 10.4161/auto.4602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aoki H, Iwado E, Eller MS, Kondo Y, et al. Telomere 3’ overhang-specific DNA oligonucleotides induce autophagy in malignant glioma cells. FASEB J. 2007;21:2918–2930. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6941com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.VanMeter A, Signore M, Pierobon M, Espina V, et al. Reverse-phase protein microarrays: application to biomarker discovery and translational medicine. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2007;7:625–633. doi: 10.1586/14737159.7.5.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishizuka S, Charboneau L, Young L, Major S, et al. Proteomic profiling of the NCI-60 cancer cell lines using new high-density reverse-phase lysate microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14229–14234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2331323100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishizuka S, Chen ST, Gwadry FG, Alexander J, et al. Diagnostic markers that distinguish colon and ovarian adenocarcinomas: identification by genomic, proteomic, and tissue array profiling. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5243–5250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishizuka S. Profiling cancer stem cells using protein array technology. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chatterjee M, Mohapatra S, Ionan A, Bawa G, et al. Diagnostic markers of ovarian cancer by high-throughput antigen cloning and detection on arrays. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1181–1190. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Yu J, Sreekumar A, Varambally S, et al. Autoantibody signatures in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1224–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen YT, Scanlan MJ, Sahin U, Tureci O, et al. A testicular antigen aberrantly expressed in human cancers detected by autologous antibody screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1914–1918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen YT, Gure AO, Tsang S, Stockert E, et al. Identification of multiple cancer/testis antigens by allogeneic antibody screening of a melanoma cell line library. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6919–6923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen YTSM, Obata Y, Old LJ, editors. Principles and practice of the biologic therapy of cancer. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2000. Identification of human tumor antigens by serological expression cloning; pp. 557–570. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen YT. Identification of human tumor antigens by serological expression cloning: an online review on SEREX. Cancer Immun. 2004 http://www.cancerimmunity.org/SEREX/

- 51.Chen YT, Gure AO, Scanlan MJ. Serological analysis of expression cDNA libraries (SEREX): an immunoscreening technique for identifying immunogenic tumor antigens. Methods Mol Med. 2005;103:207–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joos TO, Schrenk M, Hopfl P, Kroger K, et al. A microarray enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for autoimmune diagnostics. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:2641–2650. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(20000701)21:13<2641::AID-ELPS2641>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robinson WH, DiGennaro C, Hueber W, Haab BB, et al. Autoantigen microarrays for multiplex characterization of autoantibody responses. Nat Med. 2002;8:295–301. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bussow K, Nordhoff E, Lubbert C, Lehrach H, Walter G. A human cDNA library for high-throughput protein expression screening. Genomics. 2000;65:1–8. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Horn S, Lueking A, Murphy D, Staudt A, et al. Profiling humoral autoimmune repertoire of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) patients and development of a disease-associated protein chip. Proteomics. 2006;6:605–613. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lueking A, Horn M, Eickhoff H, Bussow K, et al. Protein microarrays for gene expression and antibody screening. Anal Biochem. 1999;270:103–111. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lueking A, Huber O, Wirths C, Schulte K, et al. Profiling of alopecia areata autoantigens based on protein microarray technology. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1382–1390. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500004-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eyles JE, Unal B, Hartley MG, Newstead SL, et al. Immunodominant Francisella tularensis antigens identified using proteome microarray. Proteomics. 2007;7:2172–2183. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li B, Jiang L, Song Q, Yang J, et al. Protein microarray for profiling antibody responses to Yersinia pestis live vaccine. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3734–3739. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3734-3739.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murthy T, Rolfs A, Hu Y, Shi Z, et al. A full-genomic sequence-verified protein-coding gene collection for Francisella tularensis. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Janeway CA. Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease. 6 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu Y, Rolfs A, Bhullar B, Murthy TV, et al. Approaching a complete repository of sequence-verified protein-encoding clones for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genome Res. 2007;17:536–543. doi: 10.1101/gr.6037607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Labaer J, Qiu Q, Anumanthan A, Mar W, et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 gene collection. Genome Res. 2004;14:2190–2200. doi: 10.1101/gr.2482804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zuo D, Mohr SE, Hu Y, Taycher E, et al. PlasmID: a centralized repository for plasmid clone information and distribution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D680–684. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pedersen SK, Sloane AJ, Prasad SS, Sebastian LT, et al. An immunoproteomic approach for identification of clinical biomarkers for monitoring disease: application to cystic fibrosis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1052–1060. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400175-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steller S, Angenendt P, Cahill DJ, Heuberger S, et al. Bacterial protein microarrays for identification of new potential diagnostic markers for Neisseria meningitidis infections. Proteomics. 2005;5:2048–2055. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu H, Hu S, Jona G, Zhu X, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome diagnostics using a coronavirus protein microarray. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4011–4016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510921103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davies DH, Liang X, Hernandez JE, Randall A, et al. Profiling the humoral immune response to infection by using proteome microarrays: high-throughput vaccine and diagnostic antigen discovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:547–552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408782102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davies DH, Wyatt LS, Newman FK, Earl PL, et al. Antibody profiling by proteome microarray reveals the immunogenicity of the attenuated smallpox vaccine modified vaccinia virus ankara is comparable to that of Dryvax. J Virol. 2008;82:652–663. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01706-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davies DH, Molina DM, Wrammert J, Miller J, et al. Proteome-wide analysis of the serological response to vaccinia and smallpox. Proteomics. 2007;7:1678–1686. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murthy TV, Wu W, Qiu QQ, Shi Z, et al. Bacterial cell-free system for high-throughput protein expression and a comparative analysis of Escherichia coli cell-free and whole cell expression systems. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;36:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robinson WH. Antigen arrays for antibody profiling. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bouwman K, Qiu J, Zhou H, Schotanus M, et al. Microarrays of tumor cell derived proteins uncover a distinct pattern of prostate cancer serum immunoreactivity. Proteomics. 2003;3:2200–2207. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qiu J, Madoz-Gurpide J, Misek DE, Kuick R, et al. Development of natural protein microarrays for diagnosing cancer based on an antibody response to tumor antigens. J Proteome Res. 2004;3:261–267. doi: 10.1021/pr049971u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Madoz-Gurpide J, Kuick R, Wang H, Misek DE, Hanash SM. Integral protein microarrays for the identification of lung cancer antigens in sera that induce a humoral immune response. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:268–281. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700366-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Forrester S, Qiu J, Mangold L, Partin A, et al. Ion experimental strategy for quantitative analysis of the humoral immune response to prostate cancer antigens using natural protein microarrays. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007;1:494–505. doi: 10.1002/prca.200600802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Qin S, Qiu W, Ehrlich JR, Ferdinand AS, et al. Development of a “reverse capture” autoantibody microarray for studies of antigen-autoantibody profiling. Proteomics. 2006;6:3199–3209. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ehrlich JR, Cauazzo R, Qiu W, Tassinari O, et al. A natie antigen “reverse capture” microarray platform for autoantibody profiling of prostate cancer sera. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007;1:476–485. doi: 10.1002/prca.200700012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Temple G, Lamesch P, Milstein S, Hill DE, et al. From genome to proteome: developing expression clone resources for the human genome. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 1):R31–43. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rolfs A, Hu Y, Ebert LDH, et al. A Biomedically enriched collection of 7000 human ORF clones. PLOS One. 2008;3:e1528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hudson ME, Pozdnyakova I, Haines K, Mor G, Snyder M. Identification of differentially expressed proteins in ovarian cancer using high-density protein microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17494–17499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708572104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhong L, Coe SP, Stromberg AJ, Khattar NH, et al. Profiling tumor-associated antibodies for early detection of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:513–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schweitzer B, Roberts S, Grimwade B, Shao W, et al. Multiplexed protein profiling on microarrays by rolling-circle amplification. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nbt0402-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sanchez-Carbayo M, Socci ND, Richstone L, Corton M, et al. Genomic and proteomic profiles reveal the association of gelsolin to TP53 status and bladder cancer progression. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1650–1658. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vazquez-Martin A, Colomer R, Menendez JA. Protein array technology to detect HER2 (erbB-2)-induced’cytokine signature’ in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smith L, Watson MB, O’Kane SL, Drew PJ, et al. The analysis of doxorubicin resistance in human breast cancer cells using antibody microarrays. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2115–2120. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lin Y, Huang R, Chen L, Li S, et al. Identification of interleukin-8 as estrogen receptor-regulated factor involved in breast cancer invasion and angiogenesis by protein arrays. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:507–515. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]