Abstract

Background

The ER chaperone GRP78/BiP is a homolog of the Hsp70 family of heat shock proteins, yet GRP78/BiP is not induced by heat shock but instead by ER stress. However, previous studies had not considered more physiologically relevant temperature elevation associated with febrile hyperthermia. In this report we examine the response of GRP78/BiP and other components of the ER stress pathway in cells exposed to 40°C.

Methodology

AD293 cells were exposed to 43°C heat shock to confirm inhibition of the ER stress response genes. Five mammalian cell types, including AD293 cells, were then exposed to 40°C hyperthermia for various time periods and induction of the ER stress pathway was assessed.

Principal Findings

The inhibition of the ER stress pathway by heat shock (43°C) was confirmed. In contrast cells subjected to more mild temperature elevation (40°C) showed either a partial or full ER stress pathway induction as determined by downstream targets of the three arms of the ER stress pathway as well as a heat shock response. Cells deficient for Perk or Gcn2 exhibit great sensitivity to ER stress induction by hyperthermia.

Conclusions

The ER stress pathway is induced partially or fully as a consequence of hyperthermia in parallel with induction of Hsp70. These findings suggest that the ER and cytoplasm of cells contain parallel pathways to coordinately regulate adaptation to febrile hyperthermia associated with disease or infection.

Introduction

The induction of GRP78/BiP by pharmacological reagents that perturb homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum led to the discovery of the ER stress response. Although, GRP78/BiP is a homolog of the hsp70 heat shock proteins, it is not induced by severe heat shock [1], [2], [3]. The functions of the rough ER, including protein folding, protein quality control, and trafficking of client proteins to the Golgi, are sensitive to changes in calcium and the redox state, which in turn are influenced by physiological changes in the rest of the cell and extracellular environment [4], [5]. Severe perturbations in calcium levels, redox state, or the amount or nature of client proteins can activate a cascade of events for the purpose of restoring ER homeostasis [6], [7]. Three ER resident proteins, PERK, ATF6, and IRE1, act as sensors of ER perturbations and act to mobilize the ER stress response. ATF6 and IRE1 are largely responsible for inducing the transcription of ER chaperone and folding genes (e.g. Bip, Dnajc3, and Erp72), while PERK has a dual role in temporarily repressing global protein synthesis and inducing the translation of proteins that help to coordinate the ER stress response [4], [5]. PERK and IRE1 also have important functions in regulating normal physiology and development that are unrelated to the ER stress response and involve other regulatory pathways [8], [9], [10], [11]. In contrast the heat shock response is initiated by the activation of the heat shock transcription factor (HSF) that stimulates the rapid induction of the classic heat shock genes [12], [13], [14], [15]. The heat shock genes encode chaperone proteins that help to protect cytoplasmic proteins from denaturation and assist with refolding of proteins. Hence their functions are similar to the ER chaperones that are increased in expression in lumen of the ER during ER stress. Global protein synthesis is inhibited by both heat shock and ER stress, and the mechanism of inhibition is largely mediated by phosphorylation of eIF2α which results in the inhibition of recycling of eIF2-GDP necessary for new rounds of translation initiation [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. In the case of ER stress the recovery of protein synthesis is regulated by Gadd34 [19], [20], [21], a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase-1, which targets the dephosphorylation of eIF2α. Gadd34 is likely to play an important role in regulating the recovery from heat shock as well but this has not been demonstrated.

We speculated that the ER does experience stress during heat shock, but this stress had previously gone undetected because the very high temperatures typically used in heat shock experiments resulted a global repression of transcription and translation [17], [18], [22], [23]. In particular, we surmised that the response to a milder heat shock that corresponds to the normal febrile-range hyperthermia over several hours might reveal an ER stress response.

Results

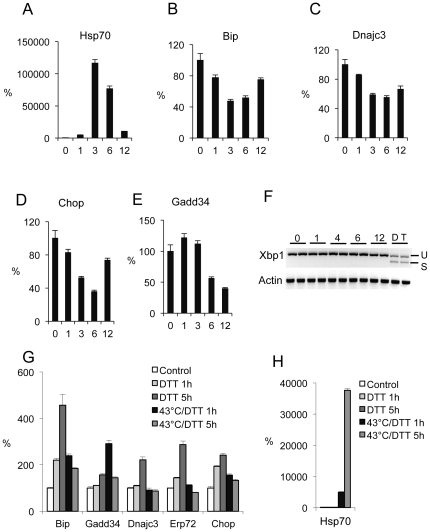

To confirm earlier studies that the key ER stress genes are not induced by a severe heat shock, AD293 transformed kidney cells were subjected to 43°C heat shock for 1–12 hours. As expected, HSP70 mRNA was potently induced, peaking at 3 hours (120,000 fold), whereas Bip, Chop, and Dnajc3 mRNA expression were repressed by approximately 50% at 3 hrs (Fig. 1A–D). Gadd34 exhibited a very small induction before being repressed at the later time points (Fig. 1E). Xbp1 splicing, a downstream target of IRE1, was not observed in heat shocked cells in contrast to a robust induction of seen in control cells treated with ER stress inducers DTT or thapsigargin (Fig. 1F). To determine if heat shock would repress the ER stress response, AD293 were treated with the potent ER stress inducer DTT at 43°C and compared to cell treated with DTT at 37°C. DTT treatment elicited the normal induction of BiP, Dnajc3, Erp72, and Chop in cells incubated at 37°C but this response to DTT was completely or partially ablated in cells incubated at 43°C (Fig. 1G). Gadd34, which is known to be induced by both ER stress and heat shock, was strongly induced in cells treated with DTT at 43°C for one hour. The meteoric induction of Hsp70 mRNA by heat shock, however, was unfazed by treatment with DTT (Fig. 1H).

Figure 1. The ER stress response pathway is repressed by a 43°C heat shock in AD293 cells.

Relative levels of Hsp70 (A), Bip (B), Gadd34 (C), Chop (D), Dnajc3 (E) mRNAs in AD293 cells incubated at 43°C for 1, 3, 6, 12 hours and normalized to mRNAs levels in control cells incubated at 37°C (mean±SEM, n = 3). (F) Xbp1 splicing in AD293 cells at 1, 4, 6, 12 hours after 43°C incubation and control cells incubated at 37°C. Positive controls of Xbp1 splicing were included as DTT (D) and thapsigargin (T) treatments. Actin mRNA levels were used as an internal control. Relative mRNA levels of ER stress related genes (G) and Hsp70 (H) in AD293 cells treated with DTT at 37°C or 43°C for 1 or 5 hours and compared to control cells at 37°C (mean±SEM, n = 3).

AD293 cells subjected to 40°C, a temperature corresponding to febrile hyperthermia, also exhibited a strong induction in HSP70 mRNA levels (Fig. 2A). However, in contrast to severe heat shock, Bip mRNA was induced 6–7 fold by 5 hours at 40°C (Fig. 2B). BIP protein level (Fig. 2G) closely followed the induction of Bip mRNA. The expression of other ER stress genes was examined including Erp72, Dnajc3, Chop, and Gadd34 (Fig. 2C–F). Erp72, Dnajc3, and Chop mRNA levels exhibited a similar pattern of delayed induction as seen for Bip. However, Gadd34 exhibited a more rapid response to 40°C hyperthermia, typically peaking at one hour and then declining thereafter. Xbp1 splicing was also strongly induced although not to the extent seen by treatment with DTT (Fig. 2H). Induction of GADD34, a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase -1 (PP1), is dependent upon phosphorylation of eIF2α in the ER stress response, and therefore we examined the phosphorylated state of eIF2α during the 40°C heat shock response of AD293 cells. As expected eIF2α phosphorylation was rapidly stimulated by 40 minutes and continued at a high level for 12 hours (Fig. 2I). A similar induction of these markers of the ER stress response was also seen at 39°C (data not shown).

Figure 2. The ER stress response pathway is induced by 40°C hyperthermia in AD293 cells.

Relative levels of Hsp70 (A), Bip (B), Erp72 (C), Dnajc3 (D), Gadd34 (E) and Chop (F) mRNAs in AD293 cells incubated at 40°C for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 hours and normalized to expression levels of cells incubated at 37°C (mean±SEM, n = 3). (G) BiP/GRP78 protein levels in AD293 cells incubated at 40°C for 0–16 hours with tubulin expression as the loading control. (H) Xbp1 mRNA splicing in AD293 cells incubated at 37°C or 40°C for 6 hours. Positive controls were included as Xbp1 mRNA splicing induced by DTT treatment. Actin mRNA levels were used as an internal control. (I) Phosphorylated eIF2α induced by 40°C from 0–12 hours with tubulin protein levels as loading controls.

The response of three other cell types to 40°C hyperthermia was determined to assess the generality of these findings. The mRNA expression of the ER stress inducible ER chaperones Bip, Erp72, and Dnajc3 were either not induced or substantially declined in human HepG2 and mouse Hepa-1 hepatocyte cell lines (Fig. 3A–D). However, Gadd34 was strongly induced whereas Chop was not. Xbp-1 RNA splicing was assessed in HepG2 cells and found to be induced to a high level (Fig. 3E) and eIF2α phosphorylation was also induced (data not shown). The pancreatic insulin secreting beta cell line, INS1-832/13 exhibited a strong induction of Gadd34 and Chop but the three ER chaperone genes, Bip, Erp72, and Dnajc3 all showed a modest decline in mRNA expression over 12 hours treatment at 40°C (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3. Hepatic and pancreatic beta cell lines display partial induction of ER stress genes in response to hyperthermia.

Relative mRNA levels of ER stress related genes (A & C) and Hsp70 (B & D) in Hepa1 and HepG2 cells, respectively, incubated at 40°C for 1, 4, 6, 12 hours and normalized to mRNA levels of cells incubated at 37°C (mean±SEM, n = 3). (E) Xbp1 splicing in HepG2 cells at 0, 1, 4, 6, 12 hours incubated at 40°C. (F) Relative mRNA levels of ER stress related genes in INS1 832/13 pancreatic beta cells incubated at 40°C for 1, 4, 6, 12 hours and normalized to mRNA levels of cells incubated at 37°C (mean±SEM, n = 3).

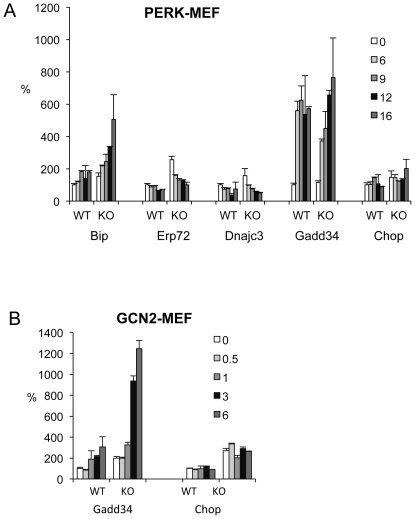

PERK eIF2α kinase is required for the induction of GADD34 and CHOP in the ER stress response induced pharmacologically by DTT, thapsigargin, or tunicamycin. To determine if induction of Gadd34 and/or Chop by hyperthermia was PERK-dependent, Perk KO mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were incubated 40°C for 0–16 hours. In wildtype MEF control cells Bip mRNA exhibited a modest induction whereas Erp72 and Dnajc3, and Chop failed to be induced or were moderately repressed (Fig. 4A). Curiously Bip mRNA was even more strongly induced in Perk KO MEFs. Erp72 and Dnajc3 both exhibited higher basal expression and were repressed by hyperthermia. Gadd34 was strongly induced in both WT and Perk KO MEFs, demonstrating that PERK is not required for the induction of Gadd34. Xbp1 RNA splicing was stimulated in both Perk KO and WT cells (not shown). GCN2 eIF2α kinase, which is widely expressed in mammalian tissues, was also examined as a candidate for regulating Gadd34 and Chop during hyperthermia. Gcn2 KO MEFs exhibit higher basal levels of Gadd34 mRNA and show a 6-fold induction by hyperthermia, whereas Gcn2 WT MEFs exhibited a more modest 3-fold induction (Fig. 4B). Similarly basal levels of Chop are considerably higher in Gcn2 KO MEFs, but Chop is not induced by hyperthermia in either genotype.

Figure 4. Deficiency of Perk or Gcn2 predisposes mouse embryonic fibroblasts to increased ER stress response induced by hyperthermia.

(A) Relative mRNA levels of ER stress related genes in Perk wildtype (WT) and knockout (KO) MEFs incubated at 40°C for 6, 9, 12, 16 hours and normalized to mRNA levels of cells incubated at 37°C (mean±SEM, n = 3). (B) Relative mRNA levels of Gadd34 and Chop in Gcn2 wildtype (WT) and knockout (KO) MEFs incubated at 40°C for 0.5, 1, 3, 6 hours and normalized to mRNA levels of cells incubated at 37°C (mean±SEM, n = 3).

Discussion

Heat shock and ER stress were previously thought to be stimulated under different circumstances, largely because GRP78/BiP was shown at the time of its discovery not to be induced by severe heat shock. We found that a more modest elevation of temperature to 40°C, which corresponds to physiological hyperthermia, elicits an ER stress response in the human AD293 kidney cell line along with a robust induction of Hsp70 in the absence of a chemical ER stress inducer. The downstream ER stress targets of ATF6 including Bip, Erp72, and Dnajc3, the downstream targets of eIF2α phosphorylation including Chop and Gadd34, and Xbp1 mRNA splicing, the downstream target of IRE1 were all induced in AD293 incubated at 40°C. Raising the temperature only 3°C, however, repressed the ER stress response seen at 40°C or in the presence of a chemical inducer of ER stress. These findings are consistent with earlier studies that showed that severe heat shock strongly represses general transcription and translation, and only the heat shock genes are transcribed [23], [24]. Therefore failure to see transcriptional induction of the ER stress genes under severe heat shock, even in the presence of a chemical inducer of ER stress, was expected. However, under more physiologically relevant conditions of febrile hyperthermia, general transcription and translation are not repressed or at least not to the extent seen in at 43°C. Thus under conditions similar to febrile hyperthermia, a heat shock response and ER stress response can occur simultaneously. Induction of both pathways simultaneously may have synergistic effects in reducing cytoplasmic and ER stress as has been suggested in studies in yeast where the heat shock response can relieve ER stress [25].

Although downstream targets of the ATF6 arm of the ER stress pathway were induced in AD293 at 40°C, generally they were not induced in the other wild-type cell types tested including two hepatocyte cell lines, a pancreatic beta cell line, and mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Targets of the PERK and IRE1 arms of the ER stress pathway, however, were generally induced in these other cell types. Bip mRNA was modestly induced in Perk and Gcn2 wildtype MEFs and strongly induced in Perk KO MEFs. Chop mRNA also exhibited considerable variation among cell lines–strongly induced in pancreatic beta cells, repressed in Hepa-1 and unchanged in HepG2 cells. Gadd34 was consistently induced in all cell lines and typically during the first hour. Although the ER stress pathway has been characterized as an integrated response that requires the activation of all three regulatory arms (IRE1, PERK, and ATF6), there are a number of examples of induction of only one or two of these regulators [26], [27], [28]. Moreover, IRE1 and PERK are known to be activated by physiological stimuli that are unrelated to ER stress or other cellular stresses [8], [11], [29], [30], [31], [32]. We have previously proposed that the normal, non-stress, functions of these regulators are co-opted during ER stress to regulate different pathways to alleviate stress [9].

Gadd34 expression was shown previously to be induced during ER stress or amino acid deprivation, as mediated by PERK and GCN2, respectively [19], [20], [21]. Curiously, Gadd34 mRNA was still strongly induced in mouse embryonic fibroblasts deficient for either Perk or Gcn2. Perhaps one or both of the other two eIF2α kinases, namely PKR and HRI, may be responsible for the induction of Gadd34 during hyperthermia [33], [34]. Basal or induced levels of some of the ER stress genes were elevated in either Perk or Gcn2 KO MEFs, suggesting that basal expression of PERK and GCN2 provides protection against hyperthermia.

In summary the ER stress response pathway can be fully activated as consequence of hyperthermia in AD293 kidney cells or partially activated in other cell lines. Because the endoplasmic reticulum faces the same challenges of protein folding and quality control during hyperthermia as does the cytoplasm we postulate that the activation of the ER stress pathway in parallel with the heat shock response orchestrate adaptation to febrile hyperthermia that occurs as consequence of disease and infection.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and treatments

AD293 [35] cells and HepG2 [36] cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1X antibiotic/antimycotic solution (Sigma, Inc.). Hepa1 [37] cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM with 8% FBS and 1X antibiotic/antimycotic solution. The INS1-832/13 [38] cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Mediatech Cellgro) supplemented with 11 mM glucose, 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 µM β-mercaptoethanol and antibiotic/ antimycotic solution. Perk+/+, Perk-/-, Gcn2+/+ and Gcn2-/- Mouse Embryo Fibroblasts (MEFs) [39], [40] were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.1 mM mercaptoethanol, 10 mM MEM nonessential amino acids (GIBCO) and antibiotic/antimycotic solution. All cell lines were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 and then switched to a 40°C or 43°C incubator in 5% CO2 during hyperthermia experiments.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted with Qiagen RNAeasy® Micro Kit (Qiagen) from all cell lines. RNA was quantitated by Quant-It ™ RiboGreen® RNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen). 1 µg RNA was used for reverse transcription with qScript™ cDNA supermix (Quanta) to generate cDNA in a 20 ul reaction volume. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with qPCR core kit for SYBR® Green I (Eurogentec/AnaSpec) by 7000 Sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). GAPDH was coamplified with genes of interest as a normalization control. The cycle differences with GAPDH are used to determine the relative intensity of genes of interests. Primers used for real-time PCR are listed in Fig. S1.

XBP-1 splicing

Human Xbp1 mRNA from AD293 cells was reverse transcribed to cDNA and amplified by PCR at an annealing temperature at 55°C and cycle number of 40 as previously described [8]. PCR products were run on 2–3% agarose gel to separate spliced Xbp1 (398 base pairs) and unspliced Xbp1 (434 base pairs).

Western blotting

Whole cell lysates were extracted with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 1 and 2 (Sigma) and subjected to Western blot analysis. Primary antibodies for BiP/GRP78 (Santa Cruz), phospho-eIF2α (Cell Signaling) and α tubulin (Sigma) were used.

Data Analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SEM (n = 3) in arbitrary units normalized to control group as indicated (%). The two-tailed Student's test was used to evaluate statistical differences between the control group and experimental groups.

Supporting Information

Primers used for quantitative real-time PCR with ABI 7000 RT PCR System.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Rong Wang for technical assistance and Christopher Newgard (Duke University) for providing the INS1 832/13 cell line.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM56957) to D.R.C. and from the American Heart Association fellowship to S.G. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Shiu RP, Pouyssegur J, Pastan I. Glucose depletion accounts for the induction of two transformation-sensitive membrane proteinsin Rous sarcoma virus-transformed chick embryo fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:3840–3844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munro S, Pelham HR. An Hsp70-like protein in the ER: identity with the 78 kd glucose-regulated protein and immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein. Cell. 1986;46:291–300. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90746-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang SC, Wooden SK, Nakaki T, Kim YK, Lin AY, et al. Rat gene encoding the 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein GRP78: its regulatory sequences and the effect of protein glycosylation on its expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:680–684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wek RC, Cavener DR. Translational control and the unfolded protein response. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:2357–2371. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorlach A, Klappa P, Kietzmann T. The endoplasmic reticulum: folding, calcium homeostasis, signaling, and redox control. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1391–1418. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sitia R, Molteni SN. Stress, protein (mis)folding, and signaling: the redox connection. Sci STKE 2004. 2004. pe27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gupta S, McGrath B, Cavener DR. PERK (EIF2AK3) regulates proinsulin trafficking and quality control in the secretory pathway. Diabetes. 2010;59:1937–1947. doi: 10.2337/db09-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavener DR, Gupta S, McGrath BC. PERK in beta cell biology and insulin biogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:714–721. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iida K, Li Y, McGrath BC, Frank A, Cavener DR. PERK eIF2 alpha kinase is required to regulate the viability of the exocrine pancreas in mice. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei J, Sheng X, Feng D, McGrath B, Cavener DR. PERK is essential for neonatal skeletal development to regulate osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:693–707. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu C. Heat shock transcription factors: structure and regulation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:441–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lis J, Wu C. Protein traffic on the heat shock promoter: parking, stalling, and trucking along. Cell. 1993;74:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morimoto RI, Sarge KD, Abravaya K. Transcriptional regulation of heat shock genes. A paradigm for inducible genomic responses. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21987–21990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murtha-Riel P, Davies MV, Scherer BJ, Choi SY, Hershey JW, et al. Expression of a phosphorylation-resistant eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha-subunit mitigates heat shock inhibition of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12946–12951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan RF, Cavener DR, Qu S. Heat shock effects on phosphorylation of protein synthesis initiation factor proteins eIF-4E and eIF-2 alpha in Drosophila. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2985–2997. doi: 10.1021/bi00009a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duncan RF, Hershey JW. Protein synthesis and protein phosphorylation during heat stress, recovery, and adaptation. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1467–1481. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Jungreis R, Harding HP, et al. Stress-induced gene expression requires programmed recovery from translational repression. Embo J. 2003;22:1180–1187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kojima E, Takeuchi A, Haneda M, Yagi A, Hasegawa T, et al. The function of GADD34 is a recovery from a shutoff of protein synthesis induced by ER stress: elucidation by GADD34-deficient mice. FASEB J. 2003;17:1573–1575. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1184fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novoa I, Zeng H, Harding HP, Ron D. Feedback inhibition of the unfolded protein response by GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2alpha. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1011–1022. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenzie SL, Henikoff S, Meselson M. Localization of RNA from heat-induced polysomes at puff sites in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1117–1121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashburner M. Patterns of puffing activity in the salivary gland chromosomes of Drosophila. V. Responses to environmental treatments. Chromosoma. 1970;31:356–376. doi: 10.1007/BF00321231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiDomenico BJ, Bugaisky GE, Lindquist S. The heat shock response is self-regulated at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Cell. 1982;31:593–603. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Chang A. Heat shock response relieves ER stress. Embo J. 2008;27:1049–1059. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeGracia DJ, Montie HL. Cerebral ischemia and the unfolded protein response. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Civelek M, Manduchi E, Riley RJ, Stoeckert CJ, Davies PF. Chronic endoplasmic reticulum stress activates unfolded protein response in arterial endothelium in regions of susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2009;105:453–461. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakayama Y, Endo M, Tsukano H, Mori M, Oike Y, et al. Molecular mechanisms of the LPS-induced non-apoptotic ER stress-CHOP pathway. J Biochem. 2010;147:471–483. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipson KL, Fonseca SG, Ishigaki S, Nguyen LX, Foss E, et al. Regulation of insulin biosynthesis in pancreatic beta cells by an endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein kinase IRE1. Cell Metab. 2006;4:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta S, McGrath B, Cavener DR. PERK regulates the proliferation and development of insulin-secreting beta-cell tumors in the endocrine pancreas of mice. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang W, Feng D, Li Y, Iida K, McGrath B, et al. PERK EIF2AK3 control of pancreatic beta cell differentiation and proliferation is required for postnatal glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2006;4:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Iida K, O'Neil J, Zhang P, Li S, et al. PERK eIF2alpha kinase regulates neonatal growth by controlling the expression of circulating insulin-like growth factor-I derived from the liver. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3505–3513. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu L, Han AP, Chen JJ. Translation initiation control by heme-regulated eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha kinase in erythroid cells under cytoplasmic stresses. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7971–7980. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.7971-7980.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wek RC. eIF-2 kinases: regulators of general and gene-specific translation initiation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:491–496. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graham FL, Smiley J, Russell WC, Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J Gen Virol. 1977;36:59–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz AL, Fridovich SE, Knowles BB, Lodish HF. Characterization of the asialoglycoprotein receptor in a continuous hepatoma line. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:8878–8881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikeguchi M, Teeter LD, Eckersberg T, Ganapathi R, Kuo MT. Structural and functional analyses of the promoter of the murine multidrug resistance gene mdr3/mdr1a reveal a negative element containing the AP-1 binding site. DNA Cell Biol. 1991;10:639–649. doi: 10.1089/dna.1991.10.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, et al. Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2000;49:424–430. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang P, McGrath B, Li S, Frank A, Zambito F, et al. The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha kinase is required for the development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the function and viability of the pancreas. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3864–3874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3864-3874.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang P, McGrath BC, Reinert J, Olsen DS, Lei L, et al. The GCN2 eIF2alpha kinase is required for adaptation to amino acid deprivation in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6681–6688. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6681-6688.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primers used for quantitative real-time PCR with ABI 7000 RT PCR System.

(PDF)