Abstract

Levels of messenger RNA (mRNA) for the α1 subunit of the GABAA receptor, which is present in 60% of cortical GABAA receptors, have been reported to be lower in layer 3 of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) in subjects with schizophrenia. This subunit is expressed in both pyramidal cells and interneurons, and thus lower α1 subunit levels in each cell population would have opposite effects on net cortical excitation. We used dual-label in situ hybridization to quantify GABAA α1 subunit mRNA expression in calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II α (CaMKIIα)-containing pyramidal cells and glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 kDa (GAD65)-containing interneurons in layer 3 of the PFC from matched schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. In subjects with schizophrenia, mean GABAA α1 subunit mRNA expression was significantly 40% lower in pyramidal cells, but was not altered in interneurons. Lower α1 subunit mRNA expression in pyramidal cells was not attributable to potential confounding factors, and thus appeared to reflect the disease process of schizophrenia. These results suggest that pyramidal cell inhibition is reduced in schizophrenia, whereas inhibition of GABA neurons is maintained. The cell type specificity of these findings may reflect a compensatory response to enhance layer 3 pyramidal cell activity in the face of the diminished excitatory drive associated with the lower dendritic spine density on these neurons.

Keywords: basket cell, calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II alpha, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 kDa, parvalbumin, working memory

INTRODUCTION

Prefrontal cortical (PFC) dysfunction in schizophrenia is associated with impaired local inhibitory signaling (Coyle, 2004; Lewis et al, 2005). For example, lower levels of the major γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-synthesizing enzyme, glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 kDa (GAD67), are consistently found in postmortem studies (Gonzalez-Burgos et al, 2010), and a single-nucleotide polymorphism in the GAD67 gene (GAD1) is associated with impaired cognitive performance and decreased PFC GAD67 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in schizophrenia subjects (Straub et al, 2007). However, the relationship of this presynaptic deficit to the fast inhibitory neurotransmission mediated by GABAA receptors on different populations of postsynaptic cells is not well studied.

Most GABAA receptors are composed of 2α, 2β and 1γ or δ-subunit (Mohler, 2006). The α1 subunit is present in over 60% of cortical GABAA receptors, and its expression is enriched in both pyramidal cells and interneurons of PFC layers 3-superficial 5 (Beneyto et al, 2011). Some (Akbarian et al, 1995; Beneyto et al, 2011; Hashimoto et al, 2008a, 2008b), but not all (Duncan et al, 2010), well-controlled studies have reported lower levels of GABAA α1 subunit mRNA in PFC gray matter from schizophrenia subjects, with this decrease most prominent in layers 3 and 4 (Beneyto et al, 2011).

As the effects of disease on gene expression might differ across subsets of neurons, analysis of α1 subunit expression in specific cell populations should have greater sensitivity for detecting disease-related differences than tissue level approaches, and thus provide greater explanatory power for determining the functional significance of disease-related differences in expression. For example, GABAA α1 receptors are present in both pyramidal cells and interneurons, and they are especially prominent at the powerful inhibitory inputs from parvalbumin (PV) basket neurons to the perisomatic region of pyramidal cells and between PV neurons (Klausberger et al, 2002; Nusser et al, 1996; Nyíri et al, 2001). Thus, lower levels of GABAA α1 receptors in pyramidal cells would increase net cortical excitation, whereas lower levels in interneurons would have the opposite effect. The present study was designed to discriminate between these alternatives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Subjects

Brain specimens from 32 subjects were recovered during autopsies conducted at the Allegheny County Medical Examiner's Office (Pittsburgh, PA) after obtaining consent from the next of kin. Inclusion criteria included ages 16–85 years, death by accident, natural causes or suicide, and death suddenly, out of the hospital, and without evidence of an agonal process. Exclusion criteria included history of intravenous drug use, hepatitis or HIV infection, neurodegenerative disorders, or mental retardation. Neuropathological examination of each brain revealed no abnormalities, except for subject 622 who had an infarction limited to the distribution of the inferior branch of the right middle cerebral artery, but PFC area 9 appeared unaffected. An independent committee of experienced research clinicians made consensus DSM-IV diagnoses for each subject, using the results of structured interviews conducted with family members and review of medical records, as previously described (Glantz and Lewis, 2000). None of the comparison subjects had any lifetime history of an Axis I diagnosis, except for one subject who had an earlier diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder that had been in remission for 39 years. Toxicology screens for all subjects revealed positive plasma alcohol levels (<0.02%) in two comparison subjects. None of the schizophrenia subjects tested positive for drugs of abuse. The two schizophrenia subjects who died of drug overdoses were positive for propoxyphene, diazepam and acetaminophen (581) and salicylate, imipramine and phenytoin (539).

To control experimental variance and reduce biological variance between groups, each schizophrenia subject (n=16) was matched for sex, and as closely as possible for age, with one healthy comparison subject. Subject groups did not differ in mean age, postmortem interval (PMI), RNA integrity number (RIN), brain pH, or freezer storage time (Table 1). The schizophrenia subject in each pair has previously been shown to express lower GABAA α1 subunit mRNA in PFC area 9, relative to its matched-comparison subject (Beneyto et al, 2011). All procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh's Committee for the Oversight of Research Involving the Dead, and Institutional Review Board for Biomedical Research.

Table 1. Comparison and Schizophrenia Subject Characteristics.

|

Comparison subjects |

Schizophrenia subjects |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair | Case | Sex/ race | Age (years) | PMI | Storage time (months) | RIN | pH | Cause of death | Case | DSM IV diagnosis | Sex/race | Age (years) | PMI | Storage time (months) | RIN | pH | Cause of death |

| 1 | 592 | M/B | 41 | 22.1 | 160.5 | 9.0 | 6.7 | ASCVD | 533 | Chronic undifferentiated schizophrenia | M/W | 40 | 29.1 | 170.3 | 8.4 | 6.8 | Accidental asphyxiation |

| 2 | 567 | F/W | 46 | 15.0 | 164.5 | 8.9 | 6.7 | Mitral valve prolapse | 537 | Schizoaffective disorder | F/W | 37 | 14.5 | 169.6 | 8.6 | 6.7 | Suicide by hanging |

| 3 | 604 | M/W | 39 | 19.3 | 158.2 | 8.6 | 7.1 | Hypoplastic coronary artery | 581 | Chronic paranoid schizophrenia; ADC; OAC | M/W | 46 | 28.1 | 162.7 | 7.9 | 7.2 | Accidental combined drug overdose |

| 4 | 1406 | M/B | 27 | 14.6 | 29.3 | 8.3 | 6.4 | Peritonitis | 547 | Schizoaffective disorder | M/B | 27 | 16.5 | 168.2 | 7.4 | 7.0 | Heat stroke |

| 5 | 685 | M/W | 56 | 14.5 | 147.6 | 8.1 | 6.6 | Hypoplastic coronary artery | 622 | Chronic undifferentiated schizophrenia | M/W | 58 | 18.9 | 155.3 | 7.4 | 6.8 | Right MCA infarction |

| 6 | 822 | M/B | 28 | 25.3 | 124.1 | 8.5 | 7.0 | ASCVD | 787 | Schizoaffective disorder; ODC | M/B | 27 | 19.2 | 130.3 | 8.4 | 6.7 | Suicide by gun shot |

| 7 | 727 | M/B | 19 | 7.0 | 141.1 | 9.2 | 7.2 | Trauma | 829 | Schizoaffective disorder; ADC; OAR | M/W | 25 | 5.0 | 122.0 | 9.3 | 6.8 | Suicide by salicylate overdose |

| 8 | 871 | M/W | 28 | 16.5 | 113.5 | 8.5 | 7.1 | Trauma | 878 | Disorganized schizophrenia; ADC | M/W | 33 | 10.8 | 112.5 | 8.9 | 6.7 | Myocardial fibrosis |

| 9 | 700 | M/W | 42 | 26.1 | 145.2 | 8.7 | 7.0 | ASCVD | 539 | Schizoaffective disorder; ADR | M/W | 50 | 40.5 | 169.4 | 8.1 | 7.1 | Suicide by combined drug overdose |

| 10 | 988 | M/W | 82 | 22.5 | 92.1 | 8.4 | 6.2 | Trauma | 621 | Chronic undifferentiated schizophrenia | M/W | 83 | 16.0 | 155.6 | 8.7 | 7.3 | Accidental asphyxiation |

| 11 | 852 | M/W | 54 | 8.0 | 121.0 | 9.1 | 6.8 | Cardiac tamponade | 781 | Schizoaffective disorder; ADR | M/B | 52 | 8.0 | 136.0 | 7.7 | 6.7 | Peritonitis |

| 12 | 987 | F/W | 65 | 21.5 | 92.1 | 9.1 | 6.8 | ASCVD | 802 | Schizoaffective disorder; ADC; ODR | F/W | 63 | 29.0 | 127.3 | 9.2 | 6.4 | Right ventricular dysplasia |

| 13 | 818 | F/W | 67 | 24.0 | 125.2 | 8.4 | 7.1 | Anaphylactic reaction | 917 | Chronic undifferentiated schizophrenia | F/W | 71 | 23.8 | 105.2 | 7.0 | 6.8 | ASCVD |

| 14 | 857 | M/W | 48 | 16.6 | 115.3 | 8.9 | 6.7 | ASCVD | 930 | Disorganized schizophrenia; ADR; OAR | M/W | 47 | 15.3 | 101.8 | 8.2 | 6.2 | ASCVD |

| 15 | 739 | M/W | 40 | 15.8 | 140.2 | 8.4 | 6.9 | ASCVD | 933 | Disorganized schizophrenia | M/W | 44 | 8.3 | 101.2 | 8.1 | 5.9 | Myocarditis |

| 16a | 546a | F/W | 37 | 23.5 | 168.5 | 8.6 | 6.7 | ASCVD | 587a | Chronic undifferentiated schizophrenia; AAR | F/B | 38 | 17.8 | 161.3 | 9.0 | 7.0 | Myocardial hypertrophy |

| Mean | 44.9 | 18.3 | 127.4 | 8.7 | 6.8 | Mean | 46.3 | 18.8 | 140.5 | 8.3 | 6.8 | ||||||

| SD | 16.7 | 5.8 | 35.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | SD | 16.3 | 9.4 | 26.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | ||||||

| Meana | 45.5 | 17.9 | 124.7 | 8.7 | 6.8 | Meana | 46.9 | 18.9 | 139.2 | 8.2 | 6.7 | ||||||

| SDa | 17.2 | 5.8 | 34.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | SDa | 16.7 | 9.7 | 26.7 | 0.7 | 0.4 | ||||||

Abbreviations: ADC, alcohol dependence, current at time of death; ADR, alcohol dependence, in remission at time of death; AAR, alcohol abuse, in remission at time of death; ODC, other substance dependence, current at time of death; ODR, other Substance dependence, in remission at time of death; OAC, other substance abuse, current at time of death; OAR, other substance abuse, in remission at time of death; M, male; F, female; B, black; W, white; PMI, postmortem interval; RIN, RNA integrity number; ASCVD, arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease; MCA, middle coronary artery.

Subject pair excluded from GAD65/α1 analysis.

Tissue Preparation

The right hemisphere of each brain was blocked coronally, immediately frozen and stored at −80 °C (Volk et al, 2000). Sections (20 μm) from the anterior–posterior level, corresponding to the middle portion of the superior frontal sulcus, were cut serially on a cryostat and collected into tubes containing Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for RNA isolation and RIN determination (Eggan et al, 2008), or mounted on SuperFrost Plus glass slides (VWR International, West Chester, PA) for in situ hybridization (ISH). The localization of dorsolateral PFC area 9 was determined by cytoarchitectonic criteria from the Nissl-stained sections (Rajkowska and Goldman-Rakic, 1995). Four sections from each subject were used in total for both experiments, such that there were two consecutive sets of sections approximately 300 μm apart. Each experiment used one section from each set, resulting in two sections per subject per experiment. Thus, a total of 64 slides were analyzed in the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II α (CaMKIIα)/α1 condition. Technical issues resulted in 13 subject pairs with two slides each, and 2 subject pairs with one slide each, for a total of 56 slides analyzed in 15 subject pairs, in the glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 kDa (GAD65)/α1 condition.

Dual Label ISH

Pyramidal cells were identified using riboprobes against CaMKIIα because its mRNA expression is specific to pyramidal cells and is unaltered in schizophrenia (Albert et al, 2002; Jones et al, 1994b; Liu and Jones, 1996; Longson et al, 1997). Interneurons were identified using riboprobes against GAD65 because its mRNA expression is specific to interneurons and is unaltered in schizophrenia (Guidotti et al, 2000; Ribak, 1978). Templates for the synthesis of riboprobes against human CaMKIIα, GAD65 and GABAA α1 subunit were generated by polymerase chain reaction. Specific primer sets amplified a 366 bp fragment corresponding to bases 2787–3153 of the human CAMK2A gene (GenBank NM_015981), a 484 bp fragment corresponding to bases 156–640 of the human GAD2 gene (GenBank NM_000818), and a 587 bp fragment corresponding to bases 846–1433 of the human GABRA1 gene (GenBank NM_000806). Nucleotide sequencing revealed 99% homology for the amplified CAMK2A and GAD2 fragments, and 100% homology for the amplified GABRA1 fragment to previously reported sequences. Sense and antisense riboprobes were transcribed in vitro in the presence of 35S-CTP (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) for the GABAA α1 subunit, and in the presence of digoxigenin (DIG) -11-UTP (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) for CaMKIIα and GAD65, using T7 or SP6 polymerases. The riboprobes were purified by centrifugation through RNeasy mini spin columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and reduced to approximately 100 bp by alkaline hydrolysis to increase tissue penetration. Sense riboprobes showed no specific labeling for either CaMKIIα or GAD65 (Supplementary Figure 1), or for GABAA α1 (Beneyto et al, 2011).

Following fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline, sections were hybridized with 35S-labeled α1 subunit riboprobe (1 × 107 cpm/ml) and DIG-labeled CaMKIIα riboprobe (100 ng), or 35S-labeled α1 subunit riboprobe (1 × 107 cpm/ml) and DIG-labeled GAD65 riboprobe (250 ng) in a standard hybridization buffer at 56 °C for 16–20 h. After hybridization, sections were washed in a 50% formamide solution at 63 °C, treated with RNase A at 37 °C, washed in 0.1 × SSC (150 mM sodium chloride, 15 mM sodium citrate) at 66 °C and air-dried. Sections were then incubated in blocking solution (3% BSA in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100) for 30 min, followed by anti-DIG antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase diluted 1 : 500 in 1% BSA, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100 (Roche) for 3 h at 4 °C. After washing and air-drying, sections were exposed to BioMax MR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 3 days to confirm 35S α1 subunit signal. Upon confirmation, slides were coated with NTB2 emulsion (Kodak), exposed for 16 days at 4 °C, developed with D-19 (Kodak), and washed. The slides were then incubated with detection buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.5), 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2; Roche) for 5 min at room temperature, then in 0.34 mg/ml nitroblue tetrazolium chloride and 0.18 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (color substrate solution) for 62–96 h at 4 °C. The color reaction was stopped with RNase-free water, the slides were air-dried, liquid overlay (VWR) was applied, and allowed to dry for 48 h, and then slides were coverslipped using Permount (Fisher Scientific).

Quantification of GABAAα1 Subunit mRNA Expression in Pyramidal Cells and Interneurons

Counting of 35S α1 subunit silver grains on coded slides was performed using a Microcomputer Imaging Device system (MCID; InterFocus Imaging, Linton, England). On each tissue section, five 1 mm-wide cortical traverses extending from the pial surface to the white matter were placed where area 9 was cut perpendicular to the cortical surface. Layer deep 3, defined as extending from 35–50% of the distance from the pial surface to the layer 6-white matter border (Glantz and Lewis, 2000), was sampled because tissue levels of α1 subunit mRNA are significantly lower in schizophrenia (Beneyto et al, 2011) and because PV cells are a predominant proportion of GABA neurons in primate PFC in this laminar location (Conde et al, 1994; Gabbott and Bacon, 1996). Four sampling frames (170 × 120 μm) were placed in layer deep 3, such that the edges of the frame were equidistant from the border of the traverse and the edge of the next sampling frame, and the top or bottom of the frames was equidistant from the layer deep 3 upper or lower border (Morris et al, 2008). In a bright-field image of the sampling frame, circles with a 30 μm diameter (708.4 μm2 area) for pyramidal cells, or 22 μm diameter (380.3 μm2 area) for interneurons (Hashimoto et al, 2003; Pierri et al, 2001; Rajkowska et al, 1998; Volk et al, 2000) were centered over each purple DIG-labeled neuron not touching the frame exclusion lines. In a dark-field image of the same sampling frame, the number of grains within each circle was calculated by the MCID system. Background grain signal was determined in each sampling frame by first free drawing around the largest area devoid of grain clusters. Next, the average number of background grains per 708.4 μm2 for pyramidal cells, or 380.3 μm2 for interneurons was calculated for each tissue section. This background measure was subtracted from each neuronal measure, resulting in the background-corrected number of α1 subunit grains per pyramidal cell or interneuron. These values were averaged across neurons for a subject, resulting in a single measure for each subject of the number of α1 subunit grains per pyramidal cell and interneuron. Total numbers of pyramidal cells (comparison: 1934; schizophrenia: 2070; t(1,15)=−0.926, p=0.369) and interneurons (comparison: 932; schizophrenia: 1033; t(1,14)=−1.774, p=0.098) sampled did not differ between subject groups.

Statistical Analysis

Two analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models were performed. The first model assessed the effect of diagnostic group on number of α1 subunit grains per neuron, using subject pair as a blocking factor, and PMI, RIN, pH, and tissue storage time as covariates because they may affect mRNA integrity, quantity, and preservation (Beneyto et al, 2009). A second unpaired ANCOVA model was performed to validate the first model, using diagnostic group as the main effect, and sex, age, PMI, pH, RIN, and storage time as covariates. These ANCOVAs revealed age as the only covariate with a significant effect. Thus, the reported unpaired ANCOVAs include only age as a covariate. As age was a pairing factor, the paired ANCOVAs include only pair as a blocking factor.

The influences of potential confounding factors on the number of α1 subunit grains per neuron in subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia were assessed with ANCOVA models, using each confounding variable (schizoaffective disorder; suicide; antidepressants, benzodiazepines, or sodium valproate, or antipsychotics at time of death; diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence ATOD) as the main effect, and sex, age, pH, RIN, PMI, and tissue storage time as covariates.

RESULTS

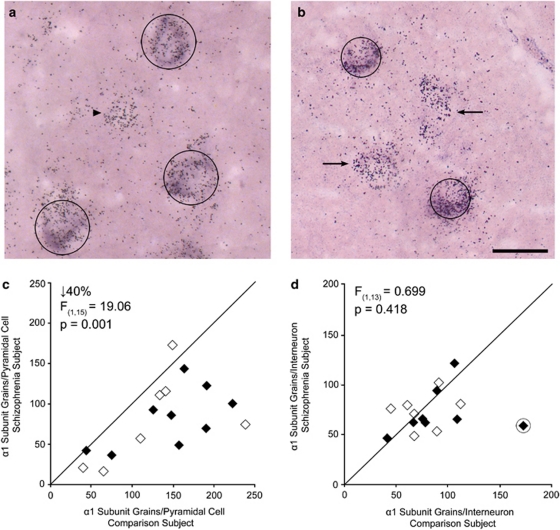

In CaMKIIα-labeled tissue, both large, DIG-labeled, pyramidal neurons with α1 subunit grain clusters, and fewer, smaller, single-labeled grain clusters, likely to be interneurons, were observed (Figure 1a). Mean (SD) α1 subunit grains per pyramidal cell were significantly 40% lower (paired: F(1,15)=19.06, p=0.001; unpaired: F(1,32)=9.774, p=0.004) in schizophrenia subjects (82.2±44.2) than in comparison subjects (136.9±59.1). In 15/16 subject pairs, the schizophrenia subject exhibited fewer α1 subunit grains per pyramidal cell than its matched comparison subject (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Representative micrographs of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II α (CaMKIIα)/α1 subunit labeling (a), and glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 kDa (GAD65)/α1 subunit labeling (b). Pyramidal cells and interneurons were identified by the purple digoxigenin (DIG) reaction product, and circles of 30 μm (a) or 22 μm (b) diameter were centered over the DIG label. GABAA α1 subunit silver grains were quantified within each circle. Note the presence of single GABAA α1-labeled grain clusters in (a; arrowhead, presumed interneuron) and (b; arrows, presumed pyramidal cells). Comparison of GABAA α1 subunit messenger RNA (mRNA) levels in pyramidal cells (c) and interneurons (d) in matched pairs of comparison subjects, and subjects with schizophrenia (filled) or schizoaffective disorder (open). Markers below the diagonal unity line indicate lower mean α1 subunit grains per neuron in the schizophrenia subject relative to its comparison subject. In (d), the outlier pair is circled. Scale bar is 30 μm.

In GAD65-labeled tissue, smaller DIG-labeled interneurons with α1 subunit grain clusters, and more numerous, larger, single-labeled grain clusters, likely to be pyramidal cells, were observed (Figure 1b). Mean α1 subunit grains per interneuron did not differ (paired: F(1,14)=1.794, p=0.202; unpaired: F(1,27)=1.515, p=0.229) between schizophrenia (72.7±20.7) and comparison (84.8±32.3) subjects (Figure 1d). The 14% difference in the group means was largely driven by one comparison subject with α1 subunit mRNA levels nearly three SD greater than the group mean. Excluding that subject pair confirmed that the group means for interneuron α1 subunit mRNA levels (schizophrenia subjects: 73.6±21.1; comparison subjects 78.5±22.2) were nearly identical (paired: F(1,13)=0.699, p=0.418; unpaired: F(1,25)=0.324, p=0.574).

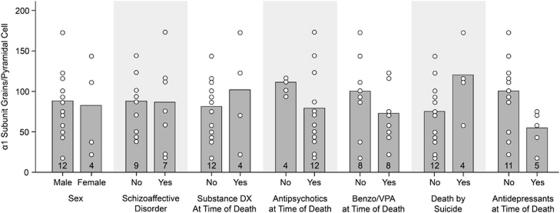

In the schizophrenia subjects, α1 subunit grains per pyramidal cell (all F(1,8)<2.909, all p>0.127) (or per interneuron (all F(1,6)<2.238, all p>0.185)) did not differ as a function of sex; schizoaffective diagnosis; a diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence ATOD; benzodiazepines, sodium valproate or antipsychotics use ATOD; or suicide (Figure 2). Eight schizophrenia subjects had a current or past diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence, and seven had no lifetime history of any substance-use diagnosis. The density of α1 subunit grains per pyramidal cell was 43 and 45% lower, respectively, in these schizophrenia subjects relative to their comparison subjects, further confirming that the group differences are associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and not an effect of substance abuse. Antidepressants ATOD did have a significant effect on the number of α1 subunit grains per pyramidal cell in schizophrenia subjects (F(1,8)=8.091, p=0.022); however, in schizophrenia subjects not on antidepressants ATOD, the density of α1 subunit grains per pyramidal was still significantly 32% lower than in comparison subjects (t(1,10)=3.520, p=0.006). Age was significantly correlated with α1 subunit mRNA expression in pyramidal cells (r=0.404, F(1,30)=5.863, p=0.022) and interneurons (r=0.451, F(1,26)=6.619, p=0.016).

Figure 2.

The effect of potential confounding factors on pyramidal cell GABAA α1 subunit mRNA levels in subjects with schizophrenia. Sex, diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, substance abuse, or dependence at time of death (ATOD); antipsychotic, benzodiazepine and/or valproic acid medications ATOD; or death by suicide did not significantly affect pyramidal cell α1 subunit messenger RNA (mRNA) levels (all p⩾0.127). Antidepressants ATOD did significantly affect pyramidal cell α1 subunit mRNA levels (p=0.022). Numbers at the bottom of bars indicate number of schizophrenia subjects per group. DX, diagnosis; Benzo, benzodiazepine; VPA, valproic acid.

DISCUSSION

In schizophrenia subjects, α1 subunit mRNA expression was significantly 40% lower in layer deep 3 pyramidal cells, but was not altered in interneurons. The selective reduction of α1 subunit mRNA in pyramidal cells appears to be a consequence of the illness, and not of factors commonly associated with the illness. Expression of α1 subunit mRNA in pyramidal cells did not differ as a function of antipsychotic medication use ATOD, consistent with earlier findings that cortical α1 subunit mRNA levels are not altered in monkeys chronically treated with haloperidol or olanzapine (Beneyto et al, 2011). Similarly, pyramidal cell levels of α1 mRNA were significantly lower in schizophrenia subjects independent of antidepressant use ATOD, consistent with previous findings that cortical α1 subunit mRNA levels are not altered in mice chronically treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Surget et al, 2009).

Lower pyramidal cell α1 subunit transcript levels could indicate: (1) downregulation of postsynaptic receptors in response to increased presynaptic GABA, (2) fewer inputs from PV basket cell axons, or (3) a homeostatic synaptic plasticity response to maintain excitatory–inhibitory (E/I) balance in the face of reduced excitatory drive to pyramidal cells. The first interpretation seems unlikely, as cortical GABA levels appear to be lower in schizophrenia due to reduced expression of the predominant synthesizing enzyme, GAD67 (Gonzalez-Burgos et al, 2010). The second interpretation is supported by the finding that the density of PV-immunoreactive boutons (putative basket cell axon terminals) is significantly lower selectively in PFC layers 3–4 in schizophrenia (Lewis et al, 2001). Additionally, genetic reductions of GAD67 in PV interneurons during development results in diminished PV basket cell axonal arborization and synapse formation (Chattopadhyaya et al, 2007). Thus, the undetectable levels of GAD67 mRNA in ∼45% of PFC PV interneurons in schizophrenia (Hashimoto et al, 2003), if present early in life, could lead to fewer PV basket cell inputs, and thus fewer synapses needing GABAA α1 receptors in postsynaptic cells. However, diminished PV basket cell axonal arbors would be expected to affect all postsynaptic cells, including other PV basket cells (Melchitzky et al, 1999), and we did not find lower α1 subunit mRNA in layer 3 interneurons, ∼50% of which express PV (Conde et al, 1994; Gabbott and Bacon, 1996). Furthermore, the lower density of PV-immunoreactive boutons in PFC layers 3–4 in schizophrenia (Lewis et al, 2001) may reflect lower levels of PV protein/axon terminal, rather than fewer axon terminals, an interpretation supported by the lower levels of PV mRNA in these same layers in schizophrenia (Hashimoto et al, 2003).

The existing data may be most consistent with a compensatory, pyramidal cell-specific downregulation of GABAA α1 receptors to maintain E/I balance in the face of fewer excitatory inputs to layer 3 pyramidal cells. The density of dendritic spines, which reflect the number of glutamatergic synapses to pyramidal cells (Gray, 1959; Harris and Kater, 1994), is significantly decreased in schizophrenia (Glantz and Lewis, 2000; Sweet et al, 2009), and this deficit is most pronounced in layer 3 (Kolluri et al, 2005). Excitatory spine deficits may represent an upstream pathology which induces homeostatic synaptic plasticity responses of lower presynaptic GABA production in PV interneurons (Hashimoto et al, 2003) and fewer postsynaptic GABAA α1 receptors in pyramidal cells, while maintaining GABAA α1 receptor levels in, and the inhibition of, interneurons. Consistent with this interpretation, experimental reductions in network activity produce fewer inputs to pyramidal cells from PV interneurons, but not other interneurons (Bartley et al, 2008), and an activity-dependent downregulation of GAD67 (Jones et al, 1994a).

Although reductions in inhibitory input from PV basket cells to pyramidal cells may restore E/I balance, the new level of balance may not be conducive to tasks requiring cognitive control. That is, strong inhibition from PV basket cells to layer 3 pyramidal cells via α1-containing GABAA receptors is critical for the neural network oscillations at γ frequency (30–80 Hz) (Gonzalez-Burgos et al, 2010; Sohal et al, 2009; Wulff et al, 2009) associated with cognitive control tasks. Thus, pre- and postsynaptic reductions in PV basket cell inhibition of layer 3 pyramidal cells, while partially restoring E/I balance, may contribute to the impaired γ-oscillations and poorer performance seen in schizophrenia subjects under tasks conditions requiring high levels of cognitive control (Cho et al, 2006; Minzenberg et al, 2010).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Holly Bazmi, Dr Stephen Eggan, and Dr Monica Beneyto. This work was supported by NIH grants F32 MH088160 to JRG, and MH084053 and MH043784 to DAL.

Dr Glausier has no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr Lewis currently receives investigator-initiated research support from the BMS Foundation, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Curridium Ltd and Pfizer, and in 2008–2010, served as a consultant in the areas of target identification and validation and new compound development to AstraZeneca, BioLine RX, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Neurogen, and SK Life Science.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Akbarian S, Huntsman MS, Kim JJ, Tafazzoli A, Potkin SG, Bunney WE, Jr, et al. GABAA receptor subunit gene expression in human prefrontal cortex: comparison of schizophrenics and controls. Cereb Cortex. 1995;5:550–560. doi: 10.1093/cercor/5.6.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert KA, Hemmings HC, Adamo AIB, Potkin SG, Akbarian S, Sandman CA, et al. Evidence for a decreased DARPP-32 in the prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:705–712. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley AF, Huang ZJ, Huber KM, Gibson JR. Differential activity-dependent, homeostatic plasticity of two neocortical inhibitory circuits. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1983–1994. doi: 10.1152/jn.90635.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneyto M, Abbott A, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Lamina-specific alterations in cortical GABAA receptor subunit Expression in schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:999–1011. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneyto M, Sibille E, Lewis DA.2009Human postmortem brain research in mental illness syndromesIn: Charney DS, Nestler EJ (eds).Neurobiology of Mental Illness Oxford University Press: New York; 202–214. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya B, Di Cristo G, Wu CZ, Knott G, Kuhlman S, Fu Y, et al. GAD67-mediated GABA synthesis and signaling regulate inhibitory synaptic innervation in the visual cortex. Neuron. 2007;54:889–903. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho RY, Konecky RO, Carter CS. Impairments in frontal cortical gamma synchrony and cognitive control in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19878–19883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609440103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde F, Lund JS, Jacobowitz DM, Baimbridge KG, Lewis DA. Local circuit neurons immunoreactive for calretinin, calbindin D-28k or parvalbumin in monkey prefrontal cortex: distribution and morphology. J Comp Neurol. 1994;341:95–116. doi: 10.1002/cne.903410109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT. The GABA-glutamate connection in schizophrenia: which is the proximate cause. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1507–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan CE, Webster MJ, Rothmond DA, Bahn S, Elashoff M, Shannon WC. Prefrontal GABA(A) receptor alpha-subunit expression in normal postnatal human development and schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Res. 2010;44:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggan SM, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Reduced cortical cannabinoid 1 receptor messenger RNA and protein expression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:772–784. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PLA, Bacon SJ. Local circuit neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (areas 24a,b,c, 25 and 32) in the monkey: II. Quantitative areal and laminar distributions. J Comp Neurol. 1996;364:609–636. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960122)364:4<609::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:65–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Burgos G, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Alterations of cortical GABA neurons and network oscillations in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EG. Axo-somatic and axo-dendritic synapses of the cerebral cortex: an electron microscopic study. J Anat. 1959;93:420–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, Gerevini VD, Dwivedi Y, Grayson DR, et al. Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Kater SB. Dendritic spines: cellular specializations imparting both stability and flexibility to synaptic function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:341–371. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Arion D, Unger T, Maldonado-Aviles JG, Morris HM, Volk DW, et al. Alterations in GABA-related transcriptome in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2008a;13:147–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Bazmi HH, Mirnics K, Wu Q, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Conserved regional patterns of GABA-related transcript expression in the neocortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2008b;165:479–489. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07081223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Volk DW, Eggan SM, Mirnics K, Pierri JN, Sun Z, et al. Gene expression deficits in a subclass of GABA neurons in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6315–6326. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Hendry SHC, DeFelipe J, Benson DL.1994aGABA neurons and their role in activity-dependent plasticity of adult primate visual cortexIn: Peters A, Rockland KS (eds).Cerebral Cortex, Vol. 10: Primary Visual Cortex in Primates Plenum Press: New York; 61–140. [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Huntley GW, Benson DL. Alpha calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II selectively expressed in a subpopulation of excitatory neurons in monkey sensory-motor cortex: comparison with GAD-67 mRNA expression. J Neurosci. 1994b;14:611–629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00611.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Roberts JD, Somogyi P. Cell type- and input-specific differences in the number and subtypes of synaptic GABAA receptors in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2513–2521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02513.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolluri N, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Lamina-specific reductions in dendritic spine density in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1200–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Cruz DA, Melchitzky DS, Pierri JN. Lamina-specific reductions in parvalbumin-immunoreactive axon terminals in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia: evidence for decreased projections from the thalamus. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1411–1422. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:312–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XB, Jones EG. Localization of alpha type II calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase at glutamatergic but not gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) synapses in thalamus and cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7332–7336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longson D, Longson CM, Jones EG. Localization of CAM II kinase-alpha, GAD, GluR2 and GABA(A) receptor subunit mRNAs in the human entorhinal cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:662–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchitzky DS, Sesack SR, Lewis DA. Parvalbumin-immunoreactive axon terminals in monkey and human prefrontal cortex: laminar, regional and target specificity of type I and type II synapses. J Comp Neurol. 1999;408:11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minzenberg MJ, Firl AJ, Yoon JH, Gomes GC, Reinking C, Carter CS. Gamma oscillatory power is impaired during cognitive control independent of medication status in first-episode schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharm. 2010;35:2590–2599. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H. GABA(A) receptor diversity and pharmacology. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:505–516. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris HM, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Alterations in somatostatin mRNA expression in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:1575–1587. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Benke D, Fritschy J-M, Somogyi P. Differential synaptic localization of two major γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor α subunits on hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11939–11944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyíri G, Freund TF, Somogyi P. Input-dependent synaptic targeting of α2-subunit-containing GABAA receptors in synapses of hippocampal pyramidal cells of the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:428–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierri JN, Volk CLE, Auh S, Sampson A, Lewis DA. Decreased somal size of deep layer 3 pyramidal neurons in the prefrontal cortex in subjects with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:466–473. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowska G, Goldman-Rakic PS. Cytoarchitectonic definition of prefrontal areas in the normal human cortex: I. Remapping of areas 9 and 46 using quantitative criteria. Cereb Cortex. 1995;5:307–322. doi: 10.1093/cercor/5.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowska G, Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS. Neuronal and glial somal size in the prefrontal cortex: a postmortem morphometric study of schizophrenia and Huntington disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:215–224. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribak CE. Aspinous and sparsely-spinous stellate neurons in the visual cortex of rats contain glutamic acid decarboxylase. J Neurocytol. 1978;7:461–478. doi: 10.1007/BF01173991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal VS, Zhang F, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature. 2009;459:698–702. doi: 10.1038/nature07991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub RE, Lipska BK, Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Callicott JH, Mayhew MB, et al. Allelic variation in GAD1 (GAD67) is associated with schizophrenia and influences cortical function and gene expression. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:854–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surget A, Wang Y, Leman S, Ibarguen-Vargas Y, Edgar N, Griebel G, et al. Corticolimbic transcriptome changes are state-dependent and region-specific in a rodent model of depression and of antidepressant reversal. Neuropsychopharm. 2009;34:1363–1380. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet RA, Henteleff RA, Zhang W, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Reduced dendritic spine density in auditory cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharm. 2009;34:374–389. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Austin MC, Pierri JN, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Decreased glutamic acid decarboxylase67 messenger RNA expression in a subset of prefrontal cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons in subjects with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:237–245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff P, Ponomarenko AA, Bartos M, Korotkova TM, Fuchs EC, Bahner F, et al. Hippocampal theta rhythm and its coupling with gamma oscillations require fast inhibition onto parvalbumin-positive interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3561–3566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813176106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.