Abstract

Maintenance and replication of mitochondrial DNA require the concerted action of several factors encoded by nuclear genome. The mitochondrial helicase Twinkle is a key player of replisome machinery. Heterozygous mutations in its coding gene, PEO1, are associated with progressive external ophthalmoplegia (PEO) characterised by ptosis and ophthalmoparesis, with cytochrome c oxidase (COX)-deficient fibres, ragged-red fibres (RRF) and multiple mtDNA deletions in muscle. Here we describe clinical, histological and molecular features of two patients presenting with mitochondrial myopathy associated with PEO. PEO1 sequencing disclosed two novel mutations in exons 1 and 4 of the gene, respectively. Although mutations in PEO1 exon 1 have already been described, this is the first report of mutation occurring in exon 4.

Keywords: Progressive external ophthalmoplegia, PEO1 (C10ORF2), Mitochondrial myopathy, mtDNA multiple deletions, COX deficiency

1. Introduction

Multiple deletions of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) are associated with different mitochondrial disorders inherited as Mendelian autosomal dominant and recessive traits. Causative mutations have been found in seven genes, mainly involved in mtDNA replication and stability maintenance. They include POLG1 (encoding the catalytic subunit of mtDNA γ-polymerase) [1], POLG2 (encoding its accessory subunit) [2], SLC25A4 (encoding the adenine nucleotide translocator ANT1) [3], PEO1 (which encodes for Twinkle, a key helicase involved in mtDNA replication) [4], TYMP (encoding thymidine phosphorylase) [5], OPA1 (encoding a dynamin-related GTPase linked to mitochondrial fusion) [6,7] and RRM2B (encoding the p53-R2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase) [8].

Recessive PEO1 mutations result in severe and early clinical presentations such as infantile-onset spinocerebellar ataxia [9] and a hepatocerebral mtDNA depletion disorder [10,11]. Conversely, dominantly inherited mutations account for autosomal dominant progressive external ophthalmoplegia (adPEO) characterised by ptosis and ophthalmoparesis, with COX-deficient and ragged-red fibres and multiple mtDNA deletions in muscle [12].

We previously reported that PEO1 mutations occur in 17.9% of PEO cases in a large cohort of patients with muscle multiple mtDNA deletions [13].

Here we present clinical and molecular features of two independent probands mainly showing ptosis and PEO. Two novel mutations were detected in PEO1 affecting exon 1 and, for the first time, exon 4, respectively.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

Patient 1 is a 43-year-old woman who came to our observation at age 20 years with a five-year history of progressive bilateral ptosis without diplopia and minimal bilateral ophthalmoplegia with referred worsening at the end of day. For this reason she underwent diagnostic screening for Myasthenia Gravis (EMG with repetitive stimulation and jitter, anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody dosage), which was normal. She therefore underwent skeletal muscle biopsy of left brachial biceps muscle. Both ptosis and ophthalmoplegia got worse in the following two years, thereafter she refused any medical follow-up and she did not change her mind even when we contacted her to inform her about the genetic results. More recently, however, we were able to contact her 76 years old mother and 79 years old father who, though initially reluctant, finally agreed in coming to our Outpatient Department to undergo clinical and genetic assessment. Their neurological examination is normal and their clinical history is poor (the mother suffers from migraine with aura and the father has mildly elevated blood pressure and benign prostatic hypertrophy). Talking with them we came to know that their daughter got progressively worse in terms of both ptosis and ophthalmoparesis to the point that her driving licence was recalled. She is otherwise strong and healthy with no overt medical problems (she refuses any medical follow-up). She got married 13 years ago and has an 11 years old healthy daughter whose picture, taken at age 10 years, does not show any eyelid ptosis.

Patient 2 is a 39-year-old woman with a several-year history of familial thyroid-hormone resistance syndrome (mother and a 34 years old brother also affected). She did not have any neuromuscular problems until 27 years of age, when she developed mild left ptosis which got progressively worse with involvement, nine years later, of the contralateral eyelid. Neurological examination now shows bilateral ptosis, external ophthalmoplegia in all gaze directions with occasional fixation diplopia in the upward gaze, mild weakness of eye orbicular muscles and moderate proximal lower limb weakness (ileopsoas muscle). She refers easy fatigability, but denies dyspnoea, dysphonia or dysphagia. EMG examination shows mild myopathic signs in orbicularis oculi and orbicularis oris muscles, as well as in limb girdle and proximal muscles of all four limbs. Cardiological examination, including EKG and echocardiography, is normal and so are serum CK and glycemia levels. At age 37 years she underwent left brachial biceps muscle biopsy.

Family history is negative for similar problems, her mother died in her fifties of cardio-pulmonary complications (she was affected with a severe form of chronic obstructive–restrictive bronchopneumopathy and secondary cardiopathy) and her father, whose parents were first cousins, is healthy. Her older sister is also healthy, whereas her 34 years old brother underwent the insertion of a pace-maker at age 28 years for cardiac arrest. He also had thyroid-hormone resistance syndrome, but did not have PEO, ptosis, muscle weakness or any central nervous system involvement.

2.2. Histochemical studies

After obtaining written informed consent, left biceps skeletal muscle biopsies were performed according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the “IRCCS Foundation Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico”. 8 μm cryostatic cross sections were processed according to standard histological/histochemical techniques. Mitochondrial enzymatic activity was demonstrated by COX, SDH and double reaction for COX and SDH [14].

The percentage of fibres lacking COX activity was calculated on skeletal muscle sections double-stained for COX and SDH. In detail, we counted the number of COX-positive and COX-negative/deficient fibres in at least 20 different fields of about 100 fibres each for every patient. For each muscle biopsy, the selected fields belonged to two sections from different muscle samples.

2.3. Molecular studies

Southern blot analysis of muscle mitochondrial DNA and PCR assay for multiple deletions were performed as described [15].

The coding sequences and splicing sites of SLC25A4, PEO1 (C10ORF2), POLG1, POLG2 and RRM2B genes were analysed as previously described [13]. GenBank reference sequence for human PEO1 is NM_021830.4.

3. Results

Muscle histochemistry on Patient 1 revealed absence of COX activity in several scattered muscle fibres, many of which also showed mitochondrial proliferation (intense SDH-positivity, RRFs). The percentage of COX-negative fibres was estimated at 10%.

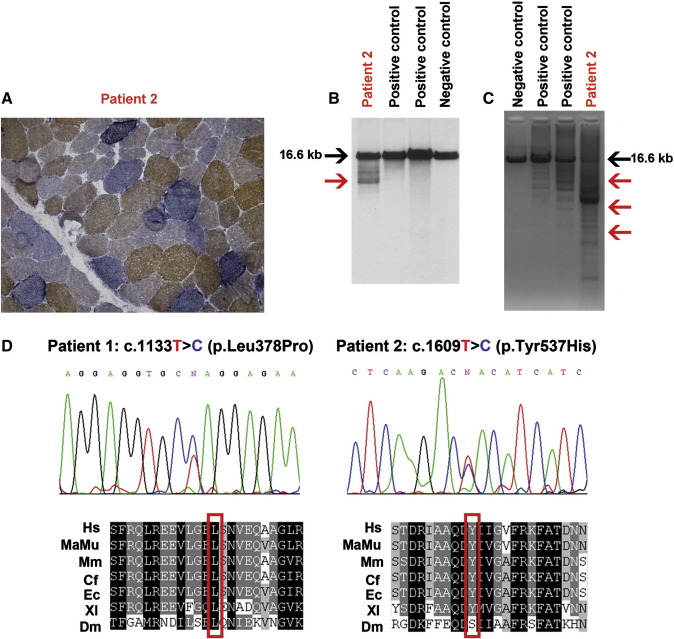

Histochemical studies on muscle from Patient 2 showed absent or severely reduced COX activity in several muscle fibres, half of which were ragged red. Considering both COX-negative and severely COX-deficient fibres, the percentage of fibres lacking COX activity was higher than 40% (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A: Histochemical double staining for COX and SDH shows severe COX deficiency and evidence of RRFs (Patient 2, 40X). B: Southern blot analysis of muscle-derived mtDNA of Patient 2, two positive controls (POLG1-mutated patients) and a negative control (adult healthy subject). The black arrow indicates wild type molecules of 16.6 kb. The red arrow indicates bands with a lower molecular weight corresponding to deleted mitochondrial genomes. C: PCR analysis of muscle-derived mtDNA of Patient 2, two positive controls and a negative control. Red arrows indicate products of amplification corresponding to deleted mitochondrial genomes. D: Electropherograms showing novel variants identified in Patient 1 (c.1133T>C) and Patient 2 (c.1609T>C) resulting in p.Leu378Pro and p.Tyr537His, respectively. The affected residues in the Twinkle protein are highly conserved in different species. Hs: Homo sapiens, MaMu: Macaca mulatta; Mm: Mus musculus; Cf: Canis familiaris; Ec: Equus caballus; Xl; Xenopus laevis; Dm: Drosophila melanogaster.

Southern blotting and long-PCR analysis on muscle-derived mtDNA molecules from the two probands showed the presence of several bands corresponding to multiple-deleted genomes (Fig. 1B and C).

PEO1 sequencing, together with SLC25A4, POLG2 and RRM2B gene analysis, was performed after the initial screening for POLG1 mutations resulted negative. Molecular analysis revealed two novel heterozygous mutations: c.1133T>C (exon 1) in Patient 1 and c.1609T>C (exon 4) in Patient 2, which are likely to result in p.Leu378Pro and p.Tyr537His changes at the protein level, respectively (Fig. 1D). The novel variants were absent in a cohort of 279 Italian and 145 pan-ethnics control subjects as well as in public available databases. The variant c.1133T>C was absent in both the parents of Patient 1 suggesting it arose de novo in the proband. The variant c.1609T>C was not found in blood-extracted DNA from the healthy father and two siblings of Patient 2. Maternal DNA was not available for molecular analysis.

4. Comment

Although the number of mitochondrial disorders caused by genetically defined defects of nuclear genes is still relatively small, great progress in this field has been made in recent years [16]. In particular, we gained an extensive (although far from complete) knowledge of nuclear encoded factors involved in mtDNA replication and stability. Mutations affecting some of these factors (POLG1, PEO1, and RRM2B) are associated with paediatric severe presentations when inherited according to a recessive pattern [17]. Conversely, dominantly inherited mutations result in an adult-onset mitochondrial disease, featuring PEO and ptosis at the clinical level and the accumulation of mtDNA multiple deletions in muscle at the molecular level [1,4,8]. As previously observed in our cohort of PEO patients, POLG1 represents the most commonly mutated gene (19.4%) followed by PEO1 (17.9%), while mutations in ANT1 are relatively rare [13]. As far as familial PEO is concerned, the involvement of PEO1 is even more significant: the occurrence of mutations increases to 26.8% of adPEO patients in our cohort.

Fratter and colleagues presented the clinical and laboratory findings in a large cohort of 33 adPEO patients, investigating their phenotypic spectrum. They disclosed a number of PEO1 molecular defects in 16 probands from 26 unrelated families [18]. A literature review of PEO1-mutated patients has been recently reported along with the description of a novel French family affected with adPEO [19].

Considering the clinical reports so far described, it is now possible to outline some conclusions: i) PEO1 mutations are more frequent in adult-onset cases than in paediatric subjects; ii) the most common clinical features are PEO and ptosis, whilst syndromic features and central nervous system involvement are less frequent than in other genetic backgrounds, such as in POLG1-mutated patients; iii) clinical onset of patients with PEO1 dominant mutations is often before the fifth decade (two thirds of the reported cases); iv) histochemical analysis of muscle biopsy confirms the presence of COX-deficient fibres in most but not all the patients; v) detection of mtDNA-deleted molecules in muscle tissue is often, but not always, observed.

The present study identifies two novel mutations in PEO1 gene associated with PEO. Our patients are two women presenting with ptosis and progressive ophthalmoparesis. The onset was at age 15 and 27 years respectively. Laboratory investigations revealed a marked defect in COX activity and the accumulation of mtDNA multiple deletions in skeletal muscle in both of them.

The mutation p.L378P affects a conserved residue located in T7 primase/helicase linker region, a known hot-spot for adPEO-linked mutations.

On the other hand, the variant p.Y537H is, to our knowledge, the first mutation arose in PEO1 exon 4 ever described so far. Indeed, all previously identified PEO1 heterozygous mutations were found in exons 1 and 2 suggesting that mutations at the 3′ end of the gene are either lethal or more tolerated than mutations at the NH2 terminus. Nevertheless, the C-terminus region of Twinkle harbours the Walker A and B motifs and the DNA binding loops: these domains are very well conserved across species because of their critical importance for the protein function; therefore a mutation occurring in this region might affect not only the structure but also directly target the functionality of the enzyme.

Matsushima and colleagues demonstrated that Drosophila mutants carrying carboxyl-terminal changes display a dose-dependent depletion of mtDNA in vitro and in vivo [20].

The tyrosine residue at position 537 is part of a highly conserved module across higher eukaryotes except for Drosophila, in which it's replaced by a serine.

Although we can't provide a definitive proof of the pathogenicity for the identified variants, some elements support their causative role in producing PEO: i) they are not found in a wide number of ethnic-matched and pan-ethnics control subjects; ii) healthy siblings of the patients don't harbour the mutations; iii) the variants affect residues located in regions important for a proper structure and function of Twinkle; iv) the signs of mitochondrial pathology disclosed in our patients are related to an impairment in mtDNA replication and their early age of onset is compatible with PEO1 mutations; v) the screening of other PEO-associated genes was negative.

Hence, it's likely that the molecular defects here described contribute to the heterogeneity of PEO1 mutations leading to human mitochondrial disease. Molecular findings in Patient 2 underline the importance of a complete sequence analysis of PEO1 coding regions.

Acknowledgements

Gratitude has to be expressed to the patients for participating in this research. We wish to thank especially the ‘Associazione Amici del Centro Dino Ferrari’ for their support.

The financial support of the research grants of Telethon projects GTB07001ER, Eurobiobank project QLTR-2001-02769 and GUP09004C is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Horvath R., Hudson G., Ferrari G., Fütterer N., Ahola S., Lamantea E. Phenotypic spectrum associated with mutations of the mitochondrial polymerase gamma gene. Brain. 2006;129:1674–1684. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longley M.J., Clark S., Yu Wai Man C., Hudson G., Durham S.E., Taylor R.W. Mutant POLG2 disrupts DNA polymerase gamma subunits and causes progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:1026–1034. doi: 10.1086/504303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaukonen J., Juselius J.K., Tiranti V., Kyttälä A., Zeviani M., Comi G.P. Role of adenine nucleotide translocator 1 in mtDNA maintenance. Science. 2000;289:782–785. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spelbrink J.N., Li F.Y., Tiranti V., Nikali K., Yuan Q.P., Tariq M. Human mitochondrial DNA deletions associated with mutations in the gene encoding Twinkle, a phage T7 gene 4-like protein localized in mitochondria. Nat Genet. 2001;28:223–231. doi: 10.1038/90058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishino I., Spinazzola A., Hirano M. Thymidine phosphorylase gene mutations in MNGIE, a human mitochondrial disorder. Science. 1999;283:689–692. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hudson G., Amati-Bonneau P., Blakely E.L., Stewart J.D., He L., Schaefer A.M. Mutation of OPA1 causes dominant optic atrophy with external ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, deafness and multiple mitochondrial DNA deletions: a novel disorder of mtDNA maintenance. Brain. 2008;131:329–337. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amati-Bonneau P., Valentino M.L., Reynier P., Gallardo M.E., Bornstein B., Boissière A. OPA1 mutations induce mitochondrial DNA instability and optic atrophy ‘plus’ phenotypes. Brain. 2008;131:338–351. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tyynismaa H., Ylikallio E., Patel M., Molnar M.J., Haller R.G., Suomalainen A. A heterozygous truncating mutation in RRM2B causes autosomal-dominant progressive external ophthalmoplegia with multiple mtDNA deletions. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikali K., Suomalainen A., Saharinen J., Kuokkanen M., Spelbrink J.N., Lönnqvist T. Infantile onset spinocerebellar ataxia is caused by recessive mutations in mitochondrial proteins Twinkle and Twinky. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2981–2990. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakonen A.H., Isohanni P., Paetau A., Herva R., Suomalainen A., Lönnqvist T. Recessive Twinkle mutations in early onset encephalopathy with mtDNA depletion. Brain. 2007;130:3032–3040. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarzi E., Goffart S., Serre V., Chrétien D., Slama A., Munnich A. Twinkle helicase (PEO1) gene mutation causes mitochondrial DNA depletion. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:579–587. doi: 10.1002/ana.21207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis S., Hutchison W., Thyagarajan D., Dahl H.H. Clinical and molecular features of adPEO due to mutations in the Twinkle gene. J Neurol Sci. 2002;201:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virgilio R., Ronchi D., Hadjigeorgiou G.M., Bordoni A., Saladino F., Moggio M. Novel Twinkle (PEO1) gene mutations in mendelian progressive external ophthalmoplegia. J Neurol. 2008;255:1384–1391. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0926-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sciacco M., Prelle A., Comi G.P., Napoli L., Battistel A., Bresolin N. Retrospective study of a large population of patients affected with mitochondrial disorders: clinical, morphological and molecular genetic evaluation. J Neurol. 2001;248:778–788. doi: 10.1007/s004150170094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moraes C.T., Atencio D.P., Oca-Cossio J., Diaz F. Techniques and pitfalls in the detection of pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations. J Mol Diagn. 2003;5:197–208. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60474-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanrooij S., Falkenberg M. The human mitochondrial replication fork in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Aug;1797(8):1378–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rötig A., Poulton J. Genetic causes of mitochondrial DNA depletion in humans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Dec;1792(12):1103–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fratter C., Gorman G.S., Stewart J.D., Buddles M., Smith C., Evans J. The clinical, histochemical, and molecular spectrum of PEO1 (Twinkle)-linked adPEO. Neurology. 2010 May 18;74(20):1619–1626. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181df099f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin-Negrier M.L., Sole G., Jardel C., Vital C., Ferrer X., Vital A. TWINKLE gene mutation: report of a French family with an autosomal dominant progressive external ophthalmoplegia and literature review. Eur J Neurol. 2010 Sep 29 doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03171.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsushima Y., Farr C.L., Fan L., Kaguni L.S. Physiological and biochemical defects in carboxyl-terminal mutants of mitochondrial DNA helicase. J Biol Chem. 2008 Aug 29;283(35):23964–23971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803674200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]