Abstract

AIM: To investigate whether there were symptom-based tendencies in the Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication in functional dyspepsia (FD) patients.

METHODS: A randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled study of H. pylori eradication for FD was conducted. A total of 195 FD patients with H. pylori infection were divided into two groups: 98 patients in the treatment group were treated with rabeprazole 10 mg twice daily for 2 wk, amoxicillin 1.0 g and clarithromycin 0.5 g twice daily for 1 wk; 97 patients in the placebo group were given placebos as control. Symptoms of FD, such as postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea, belching, epigastric pain and epigastric burning, were assessed 3 mo after H. pylori eradication.

RESULTS: By per-protocol analysis in patients with successful H. pylori eradication, higher effective rates of 77.2% and 82% were achieved in the patients with epigastric pain and epigastric burning than those in the placebo group (P < 0.05). The effective rates for postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea and belching were 46%, 36%, 52.5% and 33.3%, respectively, and there was no significant difference from the placebo group (39.3%, 27.1%, 39.1% and 31.4%) (P > 0.05). In 84 patients who received H. pylori eradication therapy, the effective rates for epigastric pain (73.8%) and epigastric burning (80.7%) were higher than those in the placebo group (P < 0.05). The effective rates for postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea and belching were 41.4%, 33.3%, 50% and 31.4%, respectively, and did not differ from those in the placebo group (P > 0.05). By intention-to-treat analysis, patients with epigastric pain and epigastric burning in the treatment group achieved higher effective rates of 60.8% and 65.7% than the placebo group (33.3% and 31.8%) (P < 0.05). The effective rates for postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea and belching were 34.8%, 27.9%, 41.1% and 26.7% respectively in the treatment group, with no significant difference from those in the placebo group (34.8%, 23.9%, 35.3% and 27.1%) (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The efficacy of H. pylori eradication has symptom-based tendencies in FD patients. It may be effective in the subgroup of FD patients with epigastric pain syndrome.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Functional dyspepsia, Eradication, Symptom

INTRODUCTION

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is considered to possess a wide spectrum of nonspecific upper gastrointestinal symptoms without any organic alteration[1], accounting for 60% of patient referrals to gastroenterology clinics[2]. Despite being barely life-threatening, this disease can lead to a poor quality of life and a high economic burden in the patients[3].

However, without a clear understanding of its pathogenesis, the optional clinical strategy for FD remains a controversial issue. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is considered to play a role in the pathogenesis of FD, and therefore, H. pylori detection and eradication are performed for FD treatment. But it is still dubious that patients with FD can benefit from H. pylori eradication. In our opinion, one of the factors that could contribute to the various outcomes of trials regarding the efficacy of H. pylori eradication for FD may be the diversity and inconsistency in FD symptoms, suggesting that this strategy might be effective only for certain dyspeptic symptoms in FD patients.

We conducted a prospective randomized, single-blind and placebo-controlled study and analyzed the efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapy for FD patients with H. pylori infection to find symptom-based predictors that can guide the clinical application of H. pylori detection and eradication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients with FD were admitted to the digestive outpatient clinics of three medical centers.

Patients who met the following criteria were enrolled into this study: (1) aged 18-75 years; (2) a definitive diagnosis of FD defined by Rome III criteria (2006)[1]; (3) absence of organic diseases, such as ulcer, bleeding, erosion, atrophy, tumor, and esophagitis in gastroscopic examination; (4) laboratory tests, ultrasonography, and X-ray showing no structural diseases in other organs, such as liver, gall bladder, pancreas, kidney, intestine, and colon; (5) both rapid urease test (RUT) and 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) confirmed H. pylori infection; and (6) not receiving antacids, antibiotics, prokinetic drugs, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs within the previous 4 wk.

We excluded the patients who (1) had a drug hypersensitivity history; (2) were previously treated with H. pylori eradication therapy; (3) were complicated with irritable bowel syndrome (defined by Rome III criteria); (4) were pregnant or nursing; (5) could not describe subjective complaint accurately; (6) were complicated with diabetes, connective tissue disease, neuromuscular disease, or any other severe systematic diseases; (7) had a history of abdominal surgeries; and (8) drank alcohol more than 40 g a day.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of each medical center and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before enrollment into this study.

Intervention

Gastroscopy and 13C-UBT were performed, and samples of the gastric mucosa were collected during gastroscopy and used for further RUT testing. Patients who were positive in both the RUT and 13C-UBT tests were considered suitable candidates for the proposed H. pylori eradication therapy. Patients were blinded to this study and randomly assigned by an independent investigator using a computer-generated random number table into one of the two groups, the treatment group and placebo group. The allocation ratio was 1:1. Patients in the treatment group were administered with rabeprazole 10 mg bd for 2 wk, and amoxycillin 1 g bd and clarithromycin 500 mg bd for 1 wk; patients in the placebo group were given placebos as control. No other medication was used during the proposed treatment.

Data collection and follow-up

The symptoms of suitable candidates were recorded on admission, and the proposed 2-wk eradication therapy was administered. Patients were returned for a 13C-UBT test 4 wk after completing the therapy, wherein negative results were considered as definitive evidence of successful eradication. All patients were followed up for 3 mo.

Assessment of clinical efficacy

Six common symptoms of FD, including postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea, belching, epigastric pain and epigastric burning, were assessed before and 3 mo after the eradication therapy. Symptom scores were graded according to severity as follows: (0) absent; (1) being aware of symptoms but no interference with daily activities; (2) having persistent discomfort with some interference with daily activities; (3) having severe discomfort and being unable to conduct daily work; and (4) suffering from worsening symptoms and having an extreme influence on daily life.

Clinical efficacy was calculated using the reduction rate of the total score of the six symptoms with the following formula: Reduction rate = (total score before treatment - total score after treatment)/ total score before treatment × 100%.

If the reduction rate was ≥ 75%, the patient was considered to experience clinical recovery; a reduction rate ≥ 50% referred to a significant improvement, a reduction rate ≥ 25% meant an improvement, and a rate < 25% meant invalidation. The total effective rate was calculated based on the clinical recovery rate and the significant improvement rate.

Safety assessment

Before treatment and during the follow-up, the basic vital signs and laboratory results, including routine blood, urine and stool tests, were monitored and documented. Any suspected adverse events observed during treatment were also recorded for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated based on the assumption of a 40% response in the drug arm vs 20% in placebo arm using the z statistic to compare dichotomous variables with α = 0.05 (two-tailed) and β = 0.20. The estimated sample size was 81 patients per arm. All data were processed using SPSS 11.0. The effective rates of symptoms were analyzed according to per-protocol (PP) and intent-to-treat (ITT) methods. The χ2 test with 2 × 2 tables was used to analyze the efficacy. P < 0.05 was considered significant difference.

RESULTS

Patient population

From September 2008 to May 2010, 195 FD patients with H. pylori infection were enrolled into this study. Number, mean age, gender distribution and total scores of symptoms before treatment were similar in the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patient population

| Treatment group | Placebo group | |

| No. of patients | 98 | 97 |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 49.2 ± 14.1 | 45.5 ± 14.9 |

| Gender (male/female) | 47/51 | 42/55 |

| Total scores of symptoms before treatment (mean ± SD) | 9.0 ± 2.8 | 8.4 ± 2.6 |

H. pylori eradication rate and safety analysis

Totally, 195 FD patients with H. pylori infection were included. Twenty-two were excluded for discontinuation of medication due to severe diarrhea (3 in the treatment group) or for being lost to follow-up (11 in the treatment group and 8 in the placebo group). The others (84 in the treatment group and 89 in the placebo group) received complete treatment and follow-up examinations on schedule. In the treatment group, the successful H. pylori eradication rate was 85.7% (72/84).

Adverse reactions documented during treatment included: mild diarrhea in 7 cases, severe diarrhea in 3 cases, stomach discomfort in 4 cases, and simultaneous diarrhea and stomach discomfort in 1 case. Except for one patient who withdrew due to severe, unbearable diarrhea, the adverse events in the patients disappeared spontaneously after the eradication treatment. The basic vital signs and routine blood, urine and stool tests were normal in all the participants.

Total clinical efficacy

By PP analysis, in 72 patients with successful H. pylori eradication, the total effective rate was 44.4% 3 mo after treatment. In 84 patients who received H. pylori eradication therapy, the total effective rate was 42.9%, which was higher than that in the 89 patients of the placebo group (21.4%) (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Total efficacy of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in functional dyspepsia patients with Helicobacter pylori infection n (%)

| Group | n | Clinical recovery | Significant improvement | Improvement | Invalidation | Total effective rates | |

| PP | Treatment group | ||||||

| Patients with successful H. pylori eradication | 72 | 11 (15.3) | 21 (29.1) | 30 (41.7) | 10 (13.9) | 32 (44.4)a | |

| Patients receiving H. pylori eradication therapy | 84 | 12 (14.3) | 24 (28.6) | 33 (39.3) | 15 (17.8) | 36 (42.9)a | |

| Placebo group | 89 | 3 (3.4) | 16 (18.0) | 34 (38.2) | 36 (40.4) | 19 (21.4) | |

| ITT | Treatment group | 98 | 12 (12.2) | 24 (24.5) | 33 (33.7) | 29 (29.6) | 36 (36.7)a |

| Placebo group | 97 | 3 (3.1) | 16 (16.5) | 34 (35.1) | 44 (45.4) | 19 (19.6) |

P < 0.05 vs the placebo group. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; PP: Per-protocol; ITT: Intent-to-treat.

By ITT analysis, the total effective rate was 36.7% in the treatment group, and 19.6% in the placebo group. There was significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Efficacy for symptom improvement

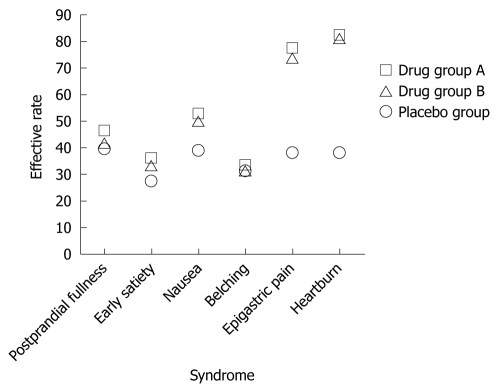

By PP analysis 3 mo after treatment, among the 72 patients with successful H. pylori eradication, those with epigastric pain and epigastric burning achieved higher effective rates of 77.2% and 82% than the patients in the placebo group (38.2% and 38.2%) (P < 0.05). The effective rates for postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea and belching were 46%, 36%, 52.5% and 33.3%, and 39.3%, 27.1%, 39.1% and 31.4%, respectively in the placebo group (P > 0.05) (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Table 3.

Respective efficacy for six common symptoms in functional dyspepsia patients n (%)

| Group | n |

Effective rates |

||||||

|

Postprandial distress syndrome |

Epigastric pain syndrome |

|||||||

| Postprandial fullness | Early satiety | Nausea | Belching | Epigastric pain | Epigastric burning | |||

| PP | Treatment group | |||||||

| Patients with successful H. pylori eradication | 72 | 23 (46.0) | 18 (36.0) | 21 (52.5) | 15 (33.3) | 44 (77.2)a | 41 (82.0)a | |

| Patients receiving H. pylori eradication therapy | 84 | 24 (41.4) | 19 (33.3) | 23 (50.0) | 16 (31.4) | 48 (73.8)a | 46 (80.7)a | |

| Placebo group | 89 | 24 (39.3) | 16 (27.1) | 18 (39.1) | 16 (31.4) | 26 (38.2) | 21 (38.2) | |

| ITT | Treatment group | 98 | 24 (34.8) | 19 (27.9) | 23 (41.1) | 16 (26.7) | 48 (60.8)a | 46 (65.7)a |

| Placebo group | 97 | 24 (34.8) | 16 (23.9) | 18 (35.3) | 16 (27.1) | 26 (33.3) | 21 (31.8) | |

P < 0.05 vs the placebo group. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; PP: Per-protocol; ITT: Intent-to-treat.

Figure 1.

Respective effective rates of six common symptoms in functional dyspepsia patients by per-protocol analysis.

Correspondingly, in 84 patients who received H. pylori eradication therapy, the effective rates for epigastric pain (73.8%) and epigastric burning (80.7%) were higher than in the placebo group (P < 0.05). The effective rates for postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea and belching were 41.4%, 33.3%, 50% and 31.4%, respectively, and did not differ from those in the placebo group (P > 0.05) (Table 3 and Figure 1).

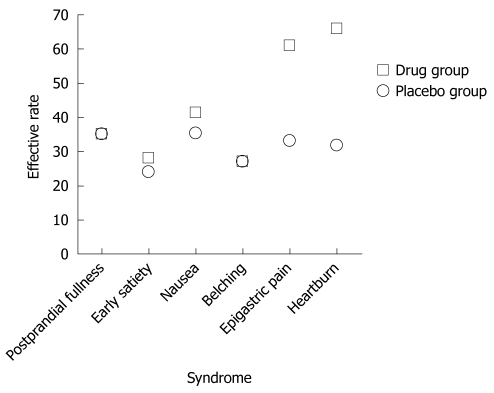

Similar results were obtained by ITT analysis. In the treatment group, patients with epigastric pain and epigastric burning also achieved higher effective rates of 60.8% and 65.7% than those in the the placebo group (33.3% and 31.8%) (P < 0.05). The effective rates for postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea and belching were 34.8%, 27.9%, 41.1% and 26.7% in the treatment group, and 34.8%, 23.9%, 35.3% and 27.1% in the placebo group (P > 0.05) (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Respective effective rates of six common symptoms in functional dyspepsia patients by intent-to-treat analysis.

DISCUSSION

FD is a common disease, accounting for a majority of upper gastrointestinal symptoms. The pathogenesis of FD is unknown. Various pathophysiological mechanisms, such as gastroduodenal dyskinesia[4], visceral paraesthesia[5], vagal dysfunction[6], H. pylori infection[7], and psychosocial factors[8], have been proposed to promote the development of FD. Without a clear understanding of its pathogenesis, it is not surprising that standard and effective strategies for treatment of this disease are still unavailable. Consequently, patients with FD now receive symptomatic treatment with prokinetics, antacids, and digestive enzymes empirically, which are prone to unfavorable responses and an extremely high risk of relapse.

H. pylori infection is the sole cause of FD that can be successfully eliminated by well-established medical interventions. Furthermore, 40%-60% of FD patients suffer from a detectable H. pylori infection[9,10], which can induce chronic inflammation and in turn the development of symptoms[11]. Evidence suggests that H. pylori-associated dyspepsia is caused by effects of the bacteria, such as increased secretion of gastric acid, elevated fasting and postprandial levels of serum gastrin, and declines in somatostatin in gastric mucosa. All these abnormalities can be corrected after H. pylori eradication[12]. If symptomatic benefits can be achieved after H. pylori eradication, the potential implications for this treatment will be enormous.

Unfortunately, whether H. pylori eradication is beneficial in FD remains controversial. Several studies have demonstrated that H. pylori eradication is efficacious[13-17]. A double-blind study of Asian populations suggested that patients with FD benefit from the H. pylori treatment, who gained as much as a 13-fold greater chance for symptom improvement[18]. Another systematic review of FD patients with H. pylori infection showed that improvement of symptoms could be achieved by up to 3.5 folds with H. pylori eradication therapy[19].

Other clinical trials, however, have noted that H. pylori eradication therapy has a moderate but statistically significant effect on FD patients with H. pylori infection[13,20]. A long-term study attributed the relief of symptoms to natural fluctuations in dyspeptic symptoms[21]. Evenly, low relief rates[22] and the persistence of symptoms[23] were observed in some reports, indicating no benefit of H. pylori eradication. Some researchers also found that dyspeptic symptoms had a negative correlation with the severity of H. pylori-associated inflammation and oxidative damage in FD patients[11].

Nevertheless, in most trials, the follow-up period was less than 1 year, creating a dearth of information about the long-term effects of H. pylori eradication. Recently, several long-term prospective researches have shown promising benefits[24,25]. Maconi et al[24] reported that at a 7-year follow-up, 33.9% of patients with successful H. pylori eradication were more likely to be asymptomatic. This percentage was slightly higher than in symptom-free patients with persisted bacteria infection. Yet, there were some confounding factors in the study. Some patients continued to use antisecretory agents, and 40% of patients still used or had been using anti-dyspeptic medications, which might bias the results and render them disputable[24]. Therefore, the evidence that FD patients with H. pylori infection benefit from H. pylori eradication therapy is inconclusive[26].

The consensus on H. pylori treatment in China, reached in 2003[27], and its new version published in 2007[28], recommended but did not stipulate H. pylori eradication therapy in “some patients with FD” or those who had “dyspeptic symptoms that were accompanied by chronic gastritis.” As such, questions on whether routine H. pylori detection should be applied in patients with FD, whether H. pylori eradication treatment must be conducted in these patients, and whether the relief of symptoms can be expected following successful eradication have become critical issues. These issues can result in negative consequences, including over-examination and over-treatment, vague evaluations of prognoses, panic psychology in patients with H. pylori infection, and decreased treatment compliance among irresponsive patients.

To our knowledge, no study has yet focused on the symptom-based tendencies of H. pylori eradication. Based on our prospective study, patients with epigastric pain and epigastric burning could experience greater improvement 3 mo after treatment than those with postprandial fullness, early satiety, nausea, and belching. The Rome III consensus classifies FD into two subgroups: postprandial distress syndrome, which presents with postprandial fullness, early satiety, postprandial nausea and over-belching; and epigastric pain syndrome, which features epigastric pain or epigastric burning[1]. This indicated that H. pylori eradication might be more effective in the subgroup of FD patients with epigastric pain syndrome.

But the mechanism of this symptom selectivity and tendency of H. pylori eradication therapy, however, is unknown. Gastric emptying in patients with FD is usually delayed or accelerated. The former can lead to abdominal distention, early satiety and nausea, and the latter can result in epigastric pain[15]. H. pylori infection is associated with faster gastric emptying and aggravates abdominal pain[15]. This result supports our findings that H. pylori eradication significantly improves the symptoms of epigastric pain. With regard to the relief of epigastric burning in our patients, the intake of antacids might be a half-convincing explanation.

In the further study, we will classify FD patients into two subgroups by the Rome III consensus to observe the symptom response to H. pylori eradication therapy, in order to investigate whether the efficacy of H. pylori eradication can be predicted by assessing the initial dyspeptic symptoms.

There are, however, regional differences in the prevalence of various dyspeptic symptoms in patients with FD. For instance, compared with Asian populations, the symptoms of epigastric pain and epigastric burning are more common in Western FD patients[29]; there is a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection in Asian populations than in Western populations[30]. Hence, global multicenter studies regarding the symptom-based tendencies of H. pylori eradication treatment are needed for further evaluation of this regimen.

COMMENTS

Background

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication is performed commonly as a treatment in functional dyspepsia (FD) patients with H. pylori infection. But whether H. pylori eradication is beneficial for the improvement of symptoms in FD is still controversial.

Research frontiers

Characteristics of FD patients with H. pylori infection who benefit from H. pylori eradication are being investigated.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Up to now, no study has yet focused on the symptom-based tendencies of H. pylori eradication in FD patients. The authors conducted a prospective randomized, single-blind and placebo-controlled study and analyzed the efficacy of H. pylori eradication therapy for FD patients with H. pylori infection to find symptom-based predictors that can guide the clinical application of H. pylori detection and eradication.

Applications

This article indicated that H. pylori eradication might be more effective in the subgroup of FD patients with epigastric pain syndrome.

Peer review

The authors hypothesized that H. pylori-infected FD patients should have significant improvement of symptoms after H. pylori eradication, and the study was designed to test it. This study (hypothesis and methodology) is simple and clearly presented. The manuscript is well organized. However, a little bit more details are expected in the methodology section.

Footnotes

Supported by The Endoscope Center of the People’s Hospital of Henan Province, Zhengzhou, China

Peer reviewer: Justin C Wu, Professor, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 9/F, Clinical Science Building, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong, China

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu P, Malagelada JR, Stanghellini V. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oshima T, Miwa H. Treatment of functional dyspepsia: where to go and what to do. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:718–719. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1865-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Epidemiology of functional dyspepsia: a global perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2661–2666. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch KL, Hong SP, Xu L. Reproducibility of gastric myoelectrical activity and the water load test in patients with dysmotility-like dyspepsia symptoms and in control subjects. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:125–129. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mertz H, Fullerton S, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Symptoms and visceral perception in severe functional and organic dyspepsia. Gut. 1998;42:814–822. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muth ER, Koch KL, Stern RM. Significance of autonomic nervous system activity in functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:854–863. doi: 10.1023/a:1005500403066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenstock S, Kay L, Rosenstock C, Andersen LP, Bonnevie O, Jørgensen T. Relation between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastrointestinal symptoms and syndromes. Gut. 1997;41:169–176. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drossman DA, Creed FH, Olden KW, Svedlund J, Toner BB, Whitehead WE. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II25–II30. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Mario F, Cavallaro LG, Nouvenne A, Stefani N, Cavestro GM, Iori V, Maino M, Comparato G, Fanigliulo L, Morana E, et al. A curcumin-based 1-week triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: something to learn from failure? Helicobacter. 2007;12:238–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Management of nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1376–1381. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811053391907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turkkan E, Uslan I, Acarturk G, Topak N, Kahraman A, Dilek FH, Akcan Y, Karaman O, Colbay M, Yuksel S. Does Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation of gastric mucosa determine the severity of symptoms in functional dyspepsia? J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:66–70. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moss SF, Legon S, Bishop AE, Polak JM, Calam J. Effect of Helicobacter pylori on gastric somatostatin in duodenal ulcer disease. Lancet. 1992;340:930–932. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92816-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American gastroenterological association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1756–1780. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Artaza Varasa T, Valle Muñoz J, Pérez-Grueso MJ, García Vela A, Martín Escobedo R, Rodríguez Merlo R, Cuena Boy R, Carrobles Jiménez JM. [Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on patients with functional dyspepsia] Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100:532–539. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082008000900002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machado RS, Reber M, Patrício FR, Kawakami E. Gastric emptying of solids is slower in functional dyspepsia unrelated to Helicobacter pylori infection in female children and teenagers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:403–408. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318159224e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz García A, Gordillo López FJ, Hermosa Hernán JC, Arranz Martínez E, Villares Rodríguez JE. [Effect of the Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with functional dyspepsia: randomised placebo-controlled trial] Med Clin (Barc) 2005;124:401–405. doi: 10.1157/13072839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malfertheiner P, MOssner J, Fischbach W, Layer P, Leodolter A, Stolte M, Demleitner K, Fuchs W. Helicobacter pylori eradication is beneficial in the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:615–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gwee KA, Teng L, Wong RK, Ho KY, Sutedja DS, Yeoh KG. The response of Asian patients with functional dyspepsia to eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:417–424. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328317b89e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin X, Li YM. Systematic review and meta-analysis from Chinese literature: the association between Helicobacter pylori eradication and improvement of functional dyspepsia. Helicobacter. 2007;12:541–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, Delaney B, Harris A, Innes M, Oakes R, Wilson S, Roalfe A, Bennett C, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD002096. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002096.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.di Mario F, Stefani N, Bò ND, Rugge M, Pilotto A, Cavestro GM, Cavallaro LG, Franzé A, Leandro G. Natural course of functional dyspepsia after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a seven-year survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2286–2295. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, Delaney B, Harris A, Innes M, Oakes R, Wilson S, Roalfe A, Bennett C, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD002096. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002096.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawakami E, Machado RS, Ogata SK, Langner M, Fukushima E, Carelli AP, Bonucci VC, Patricio FR. Furazolidone-based triple therapy for H pylori gastritis in children. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5544–5549. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i34.5544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maconi G, Sainaghi M, Molteni M, Bosani M, Gallus S, Ricci G, Alvisi V, Porro GB. Predictors of long-term outcome of functional dyspepsia and duodenal ulcer after successful Helicobacter pylori eradication--a 7-year follow-up study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:387–393. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283069db0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harvey RF, Lane JA, Nair P, Egger M, Harvey I, Donovan J, Murray L. Clinical trial: prolonged beneficial effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on dyspepsia consultations - the Bristol Helicobacter Project. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:394–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuipers EJ. Helicobacter pylori virulence: does it matter in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:11–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chinese Society of Gastroenterology. Consensus about Helicobacter pylori (2003, Tongcheng, Anhui) Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2004;24:126–127. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinese Society of Gastroenterology. Consensus about Helicobacter pylori (2007, Lusan) Zhonghua Neike Zazhi. 2008;47:346–349. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho KY, Kang JY, Seow A. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in a multiracial Asian population, with particular reference to reflux-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1816–1822. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam SK, Talley NJ. Report of the 1997 Asia Pacific Consensus Conference on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]