Abstract

AIM: To describe survival trends in patients in Northeast China diagnosed as gastric cancer.

METHODS: A review of all inpatient and outpatient records of gastric cancer patients was conducted in the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University. All the gastric cancer patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria from January 1, 1980 through December 31, 2003 were included in the study. The main outcomes were based on median survival and 3-year and 5-year survival rates, by decade of diagnosis.

RESULTS: From 1980 through 2003, the median survival for patients with gastric cancer (n = 1604) increased from 33 mo to 49 mo. The decade of diagnosis was not significantly associated with patient survival for gastric cancer (P = 0.084 for overall survival, and P = 0.150 for 5-year survival); however, the survival rate of the 2000s was remarkably higher than that of the 1980s (P = 0.019 for overall survival, and P = 0.027 for 5-year survival).

CONCLUSION: There was no significant difference of survival among each period; however, the survival rate of the 2000s was remarkably higher than that of the 1980s.

Keywords: Survival trends, Gastric cancer, Northeast China

INTRODUCTION

Although the prognosis of gastric cancer have improved due to early diagnosis, radical operation, and the development of adjuvant therapy, patients with gastric cancer still have a poor prognosis[1,2]. Since the 1980s, there have been substantial changes in the incidence of gastric cancer[3,4] and the causes for this change remain highly debated. Possible causes include the obesity epidemic, decreasing Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) prevalence, and dietary changes[5,6].

Currently, various surgical approaches are being practiced, including conventional surgery, function preserving surgery, minimally invasive surgery and less extensive lymph node dissection. Previously, surgical interventions had been associated with significant perioperative risk; recently, however, this risk appears to be decreasing[7,8]. The role of chemotherapy, both preoperatively and postoperatively, has been extensively studied[9-11]. Despite these changes in treatment, it is unclear whether the survival of patients with gastric cancer has significantly improved since the 1980s.

The purpose of the current study was to use a sample population over a 24-year period to describe changes in the survival of gastric cancer patients. We compared patient survival in the 1980s with the 1990s and the 2000s, since patient survival might have improved as a result of advances in the quality of surgical techniques and other medical management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We enrolled 1604 histologically confirmed gastric cancer patients who underwent an operation at the First Affiliated Hospital of the China Medical University between 1980 and 2003. Of these patients, 496 were allocated to 1980s, 673 to 1990s and 435 to 2000s. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) gastric cancer was histologically confirmed; (2) an operation was performed; and (3) a complete medical record was available.

Follow-up for all patients was conducted by mailing letters or telephone interviews. The follow-up was completed in December 2008, with a total follow-up rate of 89%. Clinical findings, surgical findings, pathological findings and every follow-up were collected and recorded in the database. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to estimate patient survival. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to assess associations of risk factors with survival. For univariate analyses, we put the prognostic factor of interest and the diagnosis period as covariates in the Cox regression model. In multivariate analyses, the prognostic factor detected in univariate analysis and the diagnosis period were the covariates included in the Cox regression model.

Two-sided P values were calculated for all tests and are reported here. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 16.0.

RESULTS

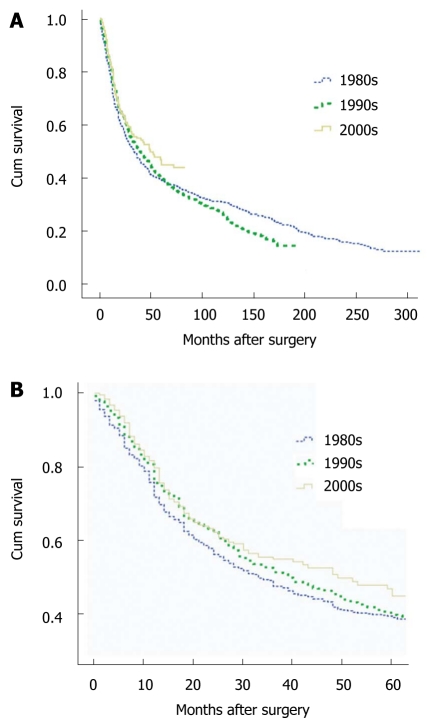

In total, 1604 patients diagnosed with gastric cancer were enrolled in the 24-year study period. The median survival for gastric cancer patients increased during the 2 decades studied from 33 mo in the 1980s, and 39 mo in the 1990s to 49 mo in the 2000s. The 3-year survival for patients in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s was 47.6% (95% CI: 43.3%-51.9%), 51.4% (95% CI: 47.7%-55.1%), and 55% (95% CI: 49.5%-60.5%), respectively. Five-year survival estimates were 39.1% (95% CI: 34.8%-43.4%), 39.8% (95% CI: 36.1%-43.5%), and 45% (95% CI: 37.9%-52.1%) in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, respectively. There was no significant difference in survival among the three periods (P = 0.084 for overall survival, and P = 0.150 for 5-year survival); however, the survival rate in the 2000s was remarkably higher than that of the 1980s (P = 0.019 for overall survival, and P = 0.027 for 5-year survival). Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with gastric cancer, by decade, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with gastric cancer by decade. A: Overall survival for gastric cancer patients; B: Five-year survival for gastric cancer patients.

For those patients who had undergone resection with curative intent, the median survival of patients was 85 mo in the 1980s, 58 mo in the 1990s, and 72 mo in the 2000s, respectively The 3-year survival for patients in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s were 65.3% (95% CI: 60.0%-70.6%), 60.8% (95% CI: 56.5%-65.1%), and 61.0% (95% CI: 55.3%-66.7%), respectively. Five-year survival estimates were 55.6% (95% CI: 50.1%-61.1%), 48.9% (95% CI: 44.6%-53.2%), and 50.4% (95% CI: 42.8%-58.0%) in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, respectively. There was no significant difference in survival among the three time periods (P = 0.169 for 5-year survival).

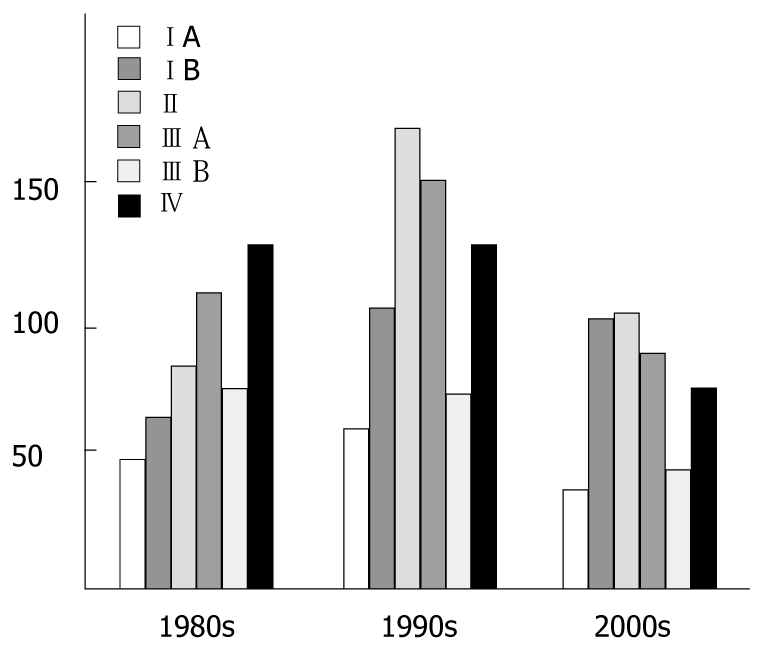

The distributions of patient characteristics by decade are shown in Table 1. Significant changes were detected in all areas except in the distribution of number of involved lymph nodes, hepatic metastasis and type of gastrectomy during the 24 years studied (P = 0.072, 0.244 and 0.073, respectively). The median age was 56 in the 1st period, 60 in the 2nd period, and 58 in the 3rd period. There was also a change in male to female ratio from 4:1 to 7:3. Among tumor factors, whole stomach tumors decreased from 12% to 5%, while T1 stage tumor and node negative cancers were found more frequently in the later periods, though this may not be significant, as early gastric cancers increased only from 20% to 24%. Curative resection rates were markedly increased during the 24-year period. Most recently, the curative resection rate was 92% (Table 1). Most cases were diagnosed at advanced stages (T2-T4, N1-N3) throughout the 2-decade period. Figure 2 shows the shift in the distribution of TNM stage of disease at diagnosis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of population from the three periods (n = 1604)

| Characteristics | 1980s (n = 496) | 1990s (n = 673) | 2000s (n = 435) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 0.000 | |||

| Median | 56 | 60 | 58 | |

| Sex (%) | 0.000 | |||

| Male | 397 (80) | 469 (70) | 306 (70) | |

| Female | 99 (20) | 204 (30) | 129 (30) | |

| Number of lymph nodes removed | 0.000 | |||

| Mean | 12 | 12 | 18 | |

| Number of involved lymph nodes | 0.072 | |||

| Mean | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.000 | |||

| Median | 6 | 5 | 5 | |

| Site of tumor (%) | 0.000 | |||

| Whole stomach | 60 (12) | 49 (7) | 23 (5) | |

| Upper stomach | 55 (11) | 80 (12) | 44 (10) | |

| Middle stomach | 39 (8) | 69 (10) | 49 (11) | |

| Lower stomach | 213 (43) | 298 (44) | 254 (58) | |

| > 2/3 stomach | 129 (26) | 177 (26) | 65 (15) | |

| Pathological tumor stage (%) | 0.003 | |||

| T1 | 99 (20) | 148 (22) | 104 (24) | |

| T2 | 179 (36) | 215 (32) | 121 (28) | |

| T3 | 154 (31) | 242 (36) | 178 (41) | |

| T4 | 64 (13) | 68 (10) | 32 (7) | |

| Pathological nodal stage (%) | 0.006 | |||

| N0 | 159 (32) | 195 (29) | 152 (35) | |

| N1 | 193 (39) | 269 (40) | 161 (37) | |

| N2 | 84 (17) | 155 (23) | 94 (22) | |

| N3 | 60 (12) | 54 (8) | 28 (6) | |

| TNM stage (%) | 0.000 | |||

| IA | 47 (10) | 58 (9) | 36 (8) | |

| IB | 62 (13) | 102 (15) | 98 (23) | |

| II | 81 (16) | 168 (25) | 100 (23) | |

| IIIA | 108 (22) | 149 (22) | 86 (20) | |

| IIIB | 73 (15) | 71 (11) | 42 (10) | |

| IV | 125 (25) | 125 (19) | 73 (17) | |

| Gross type (%) | 0.000 | |||

| Borrmann I | 15 (3) | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Borrmann II | 158 (35) | 97 (16) | 44 (11) | |

| Borrmann III | 227 (50) | 439 (71) | 311 (77) | |

| Borrmann IV | 50 (11) | 79 (13) | 47 (12) | |

| Surgery (%) | 0.000 | |||

| Absolutely curative | 277 (56) | 357 (53) | 172 (40) | |

| Relatively curative | 47 (10) | 163 (24) | 225 (52) | |

| Palliative | 172 (35) | 153 (23) | 38 (9) | |

| Lymph node dissection (%) | 0.000 | |||

| D1 | 51 (10) | 52 (8) | 46 (11) | |

| D2 | 188 (38) | 399 (59) | 347 (80) | |

| D3 | 90 (18) | 73 (11) | 16 (4) | |

| Palliative resection | 167 (34) | 149 (22) | 26 (6) | |

| Complication (%) | 0.001 | |||

| Intestinal obstruction | 16 (3) | 7 (1) | 11 (3) | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 10 (2) | 12 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Pneumonia | 3 (1) | 3 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| Abdominal abscess | 8 (2) | 11 (2) | 7 (2) | |

| Anemia | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | 4 (1) | |

| Other | 7 (1) | 12 (2) | 22 (5) | |

| Hepatic metastasis (%) | 21 (4) | 21 (3) | 10 (2) | 0.244 |

| Peritoneum metastasis (%) | 67 (14) | 50 (7) | 25 (6) | 0.000 |

| Adjunctive therapy (%) | 0 (0) | 41 (6) | 153 (35) | 0.000 |

| Type of gastrectomy (%) | 0.073 | |||

| Total | 94 (19) | 95 (14) | 76 (17) | |

| Subtotal | 402 (81) | 578 (86) | 359 (83) | |

| Combined organ resection | 0.000 | |||

| Pancreas or spleen | 53 (11) | 56 (8) | 18 (4) | |

| Liver or gall | 11 (2) | 12 (2) | 19 (4) | |

| Transverse colon | 20 (4) | 51 (8) | 52 (12) | |

| Other | 15 (3) | 20 (3) | 12 (3) |

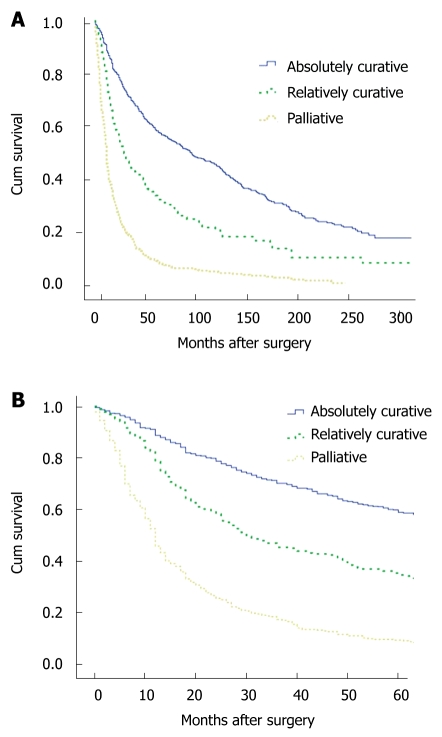

Figure 2.

The shift in the distribution of TNM stage of disease at diagnosis.

The operative mortality rate in the 1st period was 2% and 1.3% in the 2nd period, whereas it was less than 1% in the 3rd period. The multivariate Cox proportional hazards models for gastric cancer are shown in Table 2. In the Cox model for gastric cancer, adjusting for sixteen variables, there was no significant association between the decade of diagnosis and patient survival (P = 0.385). For the decade of the 1990s relative to the 1980s, the hazard ratio for gastric cancer cases was 1.025 (95% CI: 0.807-1.301), and for the decade of the 2000s relative to the 1980s, the hazard ratio was 0.914 (95% CI: 0.674-1.241). Patient survival was significantly associated with surgical extent (P = 0.000). Cases involving curative surgery were associated with prolonged survival. Figure 3 illustrate the Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with gastric cancer, by surgical intervention (absolutely curative, relatively curative, and palliative). Stage-by-stage comparison was performed among the 3 periods; for the II stage patients the survival rate of 1990s was significantly worse than that of the 1980s.

Table 2.

HR for death in population (n =1604) - univariable and multivariable analyses

|

Univariable analyses |

Multivariable analyses |

|||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (yr) | 0 | 0.005 | ||

| ≤ 55 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| > 55 | 1.383 (1.222-1.565) | 0 | 1.240 (1.036-1.484) | 0.019 |

| Sex | 0.734 | 0.582 | ||

| Male | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Female | 0.977 (0.855-1.117) | 0.734 | 1.030 (0.854-1.241) | 0.760 |

| Tumor size | 0 | 0.024 | ||

| ≤ 5 cm | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| 5-7 cm | 1.782 (1.534-2.071) | 0 | 1.250 (1.006-1.553) | 0.044 |

| > 7 cm | 2.587 (2.244-2.982) | 0 | 1.211 (0.956-1.533) | 0.113 |

| Tumor site | 0 | 0.071 | ||

| Whole stomach | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Upper stomach | 0.625 (0.489-0.798) | 0 | 1.247 (0.825-1.886) | 0.295 |

| Middle stomach | 0.358 (0.273-0.471) | 0 | 0.844 (0.541-1.315) | 0.453 |

| Lower stomach | 0.401 (0.327-0.490) | 0 | 0.846 (0.574-1.247) | 0.399 |

| > 2/3 stomach | 0.588 (0.475-0.727) | 0 | 0.845 (0.590-1.210) | 0.358 |

| Gross appearance | 0 | 0.002 | ||

| Borrmann types I | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Borrmann types II | 0.541 (0.338-0.867) | 0.011 | 0.405 (0.179-0.915) | 0.030 |

| Borrmann types III | 0.807 (0.510-1.278) | 0.361 | 0.626 (0.284-1.381) | 0.246 |

| Borrmann types IV | 1.357 (0.841-2.191) | 0.211 | 1.328 (0.317-1.672) | 0.454 |

| Tumor stage | 0 | 0.408 | ||

| T1 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| T2 | 3.336 (2.542-4.377) | 0 | 1.458 (0.797-2.667) | 0.221 |

| T3 | 4.275 (3.218-5.678) | 0 | 1.780 (0.510-2.287) | 0.841 |

| T4 | 7.873 (5.689-10.894) | 0 | 1.991 (0.459-2.590) | 0.844 |

| Lymph-node stage | 0 | 0.874 | ||

| N0 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| N1 | 2.980 (2.411-3.682) | 0 | 1.176 (0.913-2.073) | 0.127 |

| N2 | 3.430 (2.754-4.271) | 0 | 1.443 (0.595-1.826) | 0.883 |

| N3 | 5.174 (3.934-6.804) | 0 | 1.756 (0.324-2.766) | 0.518 |

| TNM stage | 0 | 0.019 | ||

| IA | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| IB | 1.920 (1.381-2.671) | 0 | 0.642 (0.288-1.431) | 0.279 |

| II | 2.645 (1.938-3.608) | 0 | 0.779 (0.293-2.068) | 0.616 |

| IIIA | 4.306 (3.171-5.847) | 0 | 1.303 (0.429-3.961) | 0.641 |

| IIIB | 4.847 (3.510-6.693) | 0 | 1.459 (0.409-5.204) | 0.561 |

| IV | 8.982 (6.613-12.199) | 0 | 3.286 (0.779-13.857) | 0.105 |

| Surgery | 0 | 0 | ||

| Absolutely curative | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Relatively curative | 1.907 (1.631-2.230) | 0 | 1.372 (1.114-1.690) | 0.003 |

| Palliative | 4.368 (3.782-5.044) | 0 | 3.361 (1.752-6.448) | 0 |

| Lymph node dissection | 0 | 0.867 | ||

| D1 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| D2 | 0.931 (0.750-1.155) | 0.515 | 1.169 (0.821-1.664) | 0.387 |

| D3 | 0.807 (0.616-1.058) | 0.121 | 1.146 (0.738-1.780) | 0.543 |

| Palliative resection | 3.236 (2.573-4.070) | 0 | 1.359 (0.457-1.612) | 0.636 |

| Joint organ removal | 0 | 0.007 | ||

| None | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Pancreas or spleen | 1.997 (1.640-2.433) | 0 | 1.086 (0.709-1.372) | 0.933 |

| Liver or gall | 1.514 (1.029-2.227) | 0.035 | 1.108 (0.649-1.891) | 0.707 |

| Transverse colon | 2.093 (1.699-2.579) | 0 | 1.466 (1.107-1.942) | 0.008 |

| Other | 2.453 (1.797-3.350) | 0 | 1.008 (0.586-1.731) | 0.978 |

| Gastrectomy | 0 | 0.512 | ||

| Total | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Subtotal | 0.573 (0.494-0.664) | 0 | 0.912 (0.693-1.200) | 0.511 |

| Hepatic metastasis | 0 | 0.796 | ||

| No | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 4.002 (2.991-5.354) | 0 | 1.285 (0.403-1.529) | 0.476 |

| Peritoneum metastasis | 0 | 0.947 | ||

| No | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 2.835 (2.359-3.406) | 0 | 1.127 (0.382-1.381) | 0.329 |

| Complication | 0.41 | 0.157 | ||

| None | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Intestinal obstruction | 0.796 (0.522-1.216) | 0.292 | 1.311 (0.670-2.565) | 0.428 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 1.474 (0.946-2.294) | 0.086 | 1.893 (0.904-3.965) | 0.091 |

| Pneumonia | 1.069 (0.400-2.856) | 0.894 | 1.207 (0.323-4.525) | 0.929 |

| Abdominal abscess | 1.212 (0.795-1.850) | 0.372 | 1.295 (0.700-2.397) | 0.410 |

| Anaemia | 0.487 (0.157-1.514) | 0.214 | 0.479 (0.116-1.980) | 0.309 |

| Other | 0.702 (0.421-1.172) | 0.176 | 0.488 (0.240-0.992) | 0.047 |

| Adjunctive therapy | 0.022 | 0.364 | ||

| No | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Yes | 0.744 (0.577-0.959) | 0.022 | 0.850 (0.643-1.124) | 0.254 |

| Diagnosis period | 0.395 | 0.385 | ||

| 1980s | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| 1990s | 1.072 (0.937-1.226) | 0.311 | 1.025 (0.807-1.301) | 0.840 |

| 2000s | 0.884 (0.735-1.063) | 0.191 | 0.914 (0.674-1.241) | 0.565 |

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with gastric cancer, by surgical intervention (absolutely curative, relatively curative, palliative). A: Overall survival for gastric cancer patients; B: Five-year survival for gastric cancer patients.

DISCUSSION

In this study of gastric cancer diagnosed in Northeast China, we found that the median survival of patients with gastric cancer actually appeared to increase between 1980 and 2000. There was a significant change in patient survival in the 2000s compared to that in the 1980s, and decade of diagnosis was not significantly associated with patient survival for gastric cancer during the 24 years. The improving prognosis of gastric cancer in recent years has been reported[12-18]. For example, the 5-year relative survival rate for gastric cancer increased from 13% to 18% in Sweden from 1960-1964 to 1985-1986[13]. However, for those patients who had a curative intent resection, there was no significant difference in survival between 1980 and 2000. As the patients operated on for palliative purpose decreased with percentages over time, it is possible that the inclusion of these patients could explain some of the trend of increasing survival between 1980 and 2000.

In this study, we found that the proportion of patients with early gastric cancer increased to 24% in the 3rd period. With the increasing incidence of early gastric cancer, node negative cancers were also increased; however, as the increasing proportions were too little and may not be significant, there were still too many patients diagnosed at an advanced stage. We also found that the incidence among women increased in the later period from 20% to 30%. We speculate that this may be due to the changes in lifestyle of Chinese women, such as more smoking and greater alcohol intake, suggesting that we should strengthen the primary prevention of gastric cancer. Currently, a surgical cure remains the only intervention that may significantly improve a patient’s chance of survival; moreover, surgery is the only treatment modality offering hope for a cure. Nevertheless, most patients die from locoregional recurrence or distant metastasis even after curative surgery for advanced stage cancers[19]. As metastasis to lymph nodes is linked to the outcome, extensive lymph node dissection is a statistically favorable prognostic factor[20]. Without surgical intervention, 2-year survival for patients with gastric cancer remained essentially zero[21]. Baba et al[22] reported that the rate of recurrence was higher in patients treated with dissection of group 1 lymph nodes than for those with dissection of group 2 or 3 nodes. In our study, 84% of the patients were treated with D2 or D3 lymph node dissection in the later period, which was much more than in the previous two periods. Besides the increase of early gastric cancer patients, advances in treatment factors mostly contributed to the improved survival.

Early diagnosis has markedly improved the survival of patients with gastric cancer, and mass screening has a definite role in diagnosing gastric cancer in its early stages[23]. In Japan, where the incidence of gastric cancer is high, survival of patients with gastric cancer does seem to be improving. This improvement appears to be the result, at least in part, of the frequent diagnosis of early-stage gastric cancer in a mass population screening program in Japan[24]. The high curative resectability rate in the screened group is related to a smaller tumor size and to a lower incidence of lymph node metastasis, liver metastasis and peritoneal dissemination than in the non-screened group. Depth of tumor invasion, lymph node involvement and distant metastasis are important prognostic factors according to the UICC/AJCC staging system of gastric cancer[25]; therefore, every attempt should be made to increase early diagnosis. Currently, gastric cancer is one of the most prevalent cancers in China, making endoscopic or radiologic examinations more common. Awareness among Chinese has also increased, similar to colorectal or prostate cancer in Western countries[26,27]. However, because of the huge rural population whose diseases are often diagnosed at a more advanced stage, current efforts at cancer prevention and early screening of high-risk populations for premalignant lesions have not resulted in a significant change in the stage of presentation of disease. Following the mass population screening being carried out widely in China, especially these past ten years, the proportion of early gastric cancer has increased very slowly.

Another important change observed in this study was the decreased prevalence of operative mortality. Although the surgical extent of recent years was more extensive than before, postoperative mortality in the 3rd period was decreased to less than 1%. The large decrease in operative mortality is due to improved surgical techniques and also to improvements in anesthesia, metabolic care and intravenous nutrition[28]. Besides these factors, the accumulation of treatment experience with gastric cancer and becoming a large volume hospital also have an impact on the improved treatment outcome of gastric cancer patients[29-34]. The specialization in gastric cancer treatment might also influence the lower mortality rate, especially in addition to technical advances.

Therefore, currently in China, we need increased efforts at refining prevention and early diagnosis of gastric cancer as only resection offers the best hope for a cure[21]. We should put emphasis on rural gastric cancer screening, improve the rural level of diagnosis and treatment, and progress the health education of gastric cancer-related knowledge.

COMMENTS

Background

Although the results of gastric cancer have improved due to early diagnosis, radical operation, and the development of adjuvant therapy, patients with gastric cancer still have poor prognosis. To describe survival trends in patients in Northeast China diagnosed as gastric cancer, the authors conducted a review of records of gastric cancer patients from 1980 to 2003 in the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University.

Research frontiers

Currently, gastric cancer in China is one of the most prevalent cancers, making endoscopic or radiologic examinations more common. However, because of the huge rural population whose diseases are often diagnosed at a later stage, current efforts at cancer prevention and early screening of high-risk populations for premalignant lesions have not resulted in a significant change in the stage of presentation of disease, and following the mass population screening being carried out widely in China, especially these ten years, the proportion of early gastric cancer has increased very slowly.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In this article, the authors found that there was no significant difference of survival among the three periods. Besides that, they also found that the proportion of patients with early gastric cancer increased in the later period, as well as the proportion of node negative cancers, and the incidence among women increased from 20% to 30%.

Applications

All the findings indicate that, nowadays in China, the authors need increased efforts at refining primary prevention and early diagnosis of gastric cancer as only resection offers the best hope for cure, and they should put emphasis on rural gastric cancer screening, improve the rural level of diagnosis and treatment, and improve health education with regard to gastric cancer-related knowledge.

Peer review

Dr. Zhang et al. described survival trends of gastric cancer among Chinese between 1980 and 2003. Although there is no significant change in survival between these periods, the authors observed a significantly increased survival rate in 2000s as compared to that of 1980s. Results of this study were supported by many previous studies. Strengths of this study are (1) a large sample size; and (2) long follow-up data.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Jong Park, PhD, MPH, MS, Associate Professor, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, College of Medicine, University of South Florida, 12902 Magnolia Dr. MRC209, Tampa, FL 33612, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Dicken BJ, Bigam DL, Cass C, Mackey JR, Joy AA, Hamilton SM. Gastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directions. Ann Surg. 2005;241:27–39. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000149300.28588.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Angelica M, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Turnbull AD, Bains M, Karpeh MS. Patterns of initial recurrence in completely resected gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240:808–816. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143245.28656.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiologic trends in esophageal and gastric cancer in the United States. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2002;11:235–256. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3207(02)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locke GR, Talley NJ, Carpenter HA, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Changes in the site- and histology-specific incidence of gastric cancer during a 50-year period. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1750–1756. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90740-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW, Fraumeni JF. Rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA. 1991;265:1287–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crane SJ, Richard Locke G, Harmsen WS, Diehl NN, Zinsmeister AR, Joseph Melton L, Romero Y, Talley NJ. The changing incidence of oesophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma by anatomic sub-site. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalrymple-Hay MJ, Evans KB, Lea RE. Oesophagectomy for carcinoma of the oesophagus and oesophagogastric junction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:626–630. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen LS, Pilegaard HK, Puho E, Pahle E, Melsen NC. Outcome after transthoracic resection of carcinoma of the oesophagus and oesophago-gastric junction. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:191–196. doi: 10.1177/145749690509400303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosset JF, Lorchel F, Mantion G, Buffet J, Créhange G, Bosset M, Chaigneau L, Servagi S. Radiation and chemoradiation therapy for esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:239–245. doi: 10.1002/jso.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urschel JD, Vasan H. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials that compared neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgery to surgery alone for resectable esophageal cancer. Am J Surg. 2003;185:538–543. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Survival of Cancer Patients in Europe: The EUROCARE-2 study. IARC Sci Publ. 1999:1–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansson LE, Sparén P, Nyrén O. Survival in stomach cancer is improving: results of a nationwide population-based Swedish study. Ann Surg. 1999;230:162–169. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maehara Y, Kakeji Y, Oda S, Takahashi I, Akazawa K, Sugimachi K. Time trends of surgical treatment and the prognosis for Japanese patients with gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:986–991. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Msika S, Benhamiche AM, Jouve JL, Rat P, Faivre J. Prognostic factors after curative resection for gastric cancer. A population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:390–396. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitamura K, Yamaguchi T, Sawai K, Nishida S, Yamamoto K, Okamoto K, Taniguchi H, Hagiwara A, Takahashi T. Chronologic changes in the clinicopathologic findings and survival of gastric cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:3471–3480. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.12.3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee WJ, Lee WC, Houng SJ, Shun CT, Houng RL, Lee PH, Chang KJ, Wei TC, Chen KM. Survival after resection of gastric cancer and prognostic relevance of systematic lymph node dissection: twenty years experience in Taiwan. World J Surg. 1995;19:707–713. doi: 10.1007/BF00295910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jatzko GR, Lisborg PH, Denk H, Klimpfinger M, Stettner HM. A 10-year experience with Japanese-type radical lymph node dissection for gastric cancer outside of Japan. Cancer. 1995;76:1302–1312. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951015)76:8<1302::aid-cncr2820760803>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoo CH, Noh SH, Kim YI, Min JS. Comparison of prognostic significance of nodal staging between old (4th edition) and new (5th edition) UICC TNM classification for gastric carcinoma. International Union Against Cancer. World J Surg. 1999;23:492–497; discussion 497-498. doi: 10.1007/pl00012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maehara Y, Moriguchi S, Kakeji Y, Orita H, Haraguchi M, Korenaga D, Sugimachi K. Prognostic factors in adenocarcinoma in the upper one-third of the stomach. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;173:223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crane SJ, Locke GR, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Romero Y, Talley NJ. Survival trends in patients with gastric and esophageal adenocarcinomas: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1087–1094. doi: 10.4065/83.10.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baba H, Maehara Y, Takeuchi H, Inutsuka S, Okuyama T, Adachi Y, Akazawa K, Sugimachi K. Effect of lymph node dissection on the prognosis in patients with node-negative early gastric cancer. Surgery. 1995;117:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abe S, Lightdale CJ, Brennan MF. The Japanese experience with endoscopic ultrasonography in the staging of gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:586–591. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arisue T, Tamura K, Tebayashi A. [End results of gastric cancer detected by mass survey: analysis using the relative survival rate curve] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1988;15:929–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz A, Balch CM, Haller DG, Morrow M. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korean Gastric Cancer Association. Nationwide Gastric Cancer Report in Korea. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2002;2:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee HJ, Yang HK, Ahn YO. Gastric cancer in Korea. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:177–182. doi: 10.1007/s101200200031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sue-Ling HM, Johnston D, Martin IG, Dixon MF, Lansdown MR, McMahon MJ, Axon AT. Gastric cancer: a curable disease in Britain. BMJ. 1993;307:591–596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6904.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, Welch HG, Wennberg DE. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bach PB, Cramer LD, Schrag D, Downey RJ, Gelfand SE, Begg CB. The influence of hospital volume on survival after resection for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:181–188. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, Cohen AM, Warren JL, Begg CB. Influence of hospital procedure volume on outcomes following surgery for colon cancer. JAMA. 2000;284:3028–3035. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, Brennan MF. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA. 1998;280:1747–1751. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hillner BE, Smith TJ, Desch CE. Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: importance in quality of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2327–2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.11.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birkmeyer JD, Sun Y, Wong SL, Stukel TA. Hospital volume and late survival after cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2007;245:777–783. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000252402.33814.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]