Abstract

Purpose

Queen's Heart, the cardiac service line at the Queens Medical Center (QMC), Honolulu, Hawai‘i, recognizes the importance of closing the health disparity gap that affects the Native Hawaiian population. The purpose of this study was to examine the process and outcomes of health care among Native Hawaiians with heart disease, and to evaluate the impact of a multidisciplinary, culturally sensitive effort to improve quality of care.

An inpatient program was created by assembling a team of practitioners who have an affinity for Native Hawaiian culture to address the health care of the Native Hawaiian people.

Methods

All Native Hawaiian patients who were admitted to The Queen's Medical Center from January 2007 to December 2008 became participants of the program. Baseline outcomes data for cardiac core measures, length of stay, 30 day readmission rates, and adverse events were reviewed by the team before the study was initiated. Educational materials were developed to provide culturally specific disease management information to patients and family members. The patient educators and discharge counselors provided patients with the education and tools they needed to engage in self care management. Heart failure disease management ensured that all Native Hawaiian patients receive appropriate quality care, individualized heart failure education, and a definitive plan for out patient follow up. The Integrative Care Program provided a holistic perspective of healing.

Results

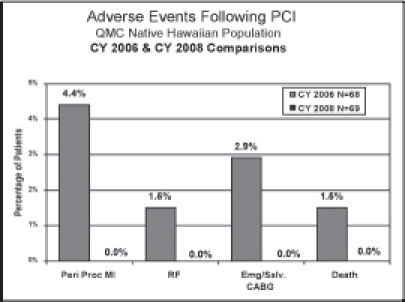

All quality indicators for Native Hawaiian patients with cardiac disease have improved. Patient satisfaction rates have remained at the 99th percentile. There has been a marked improvement in adverse events following percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) for Native Hawaiian patients. Readmissions that occurred in less than 30 days for patients admitted with myocardial infarctions and heart failure have improved and are now essentially the same as all other patient populations.

Conclusions

Culturally sensitive and patient centered care, delivered by the team of specialists from Queen's Heart, has allowed patients to incorporate cultural preferences into their care and recovery. Readmission rates have decreased, mortality rates have improved, and patient and family satisfaction is enhanced.

Introduction

There is an increasing burden of cardiometabolic disorders among minority populations in the United States.1 Most of the studies evaluating health care disparities have focused on the differences between African American populations and those with a primarily European ancestry. The State of Hawai‘i has the largest number of peoples who identify themselves as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders in the United States. In 2007, Queen's Heart developed a program to address the cardiometabolic health disparities of hospitalized Native Hawaiians. The Queen's Heart Native Hawaiian Health Initiative (QHNHHI) was supported by the Board of Trustees and CEO of The Queen's Health Systems.

Until recently the health care disparities of this population of people have been under studied.2 The data for Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders with heart disease are scarce. The available data does indicate that these ethnic groups have a higher rate of risk factors for cardiovascular related conditions including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.2–3 Asian and Pacific Islanders, with heart failure, were found to have extended hospitalizations and require more medical interventions than Caucasians.3 The purpose of this study was to examine the process and outcomes of health care among Native Hawaiians with heart disease, and to evaluate the impact of a multidisciplinary and culturally sensitive effort to improve quality of care.

Methods

The Queen's Heart Native Hawaiian Health Initiative was based on The Queen's Medical Center (QMC) philosophy of care, Lokomaika‘i (Inner Health) and was guided by principles of patient and family centered care, culturally centered care, collaboration between all health care team members, and delivery of care with an emphasis on education. Building on an ongoing performance improvement infrastructure, QHNHHI was specifically tailored to address health care disparities among Native Hawaiians and also to provide high-quality care for all hospitalized patients.

A team of specialized practitioners, with an affinity for Native Hawaiian culture, developed educational materials that would provide culturally appropriate disease management information to patients and families. Patients were provided with scales for daily weights and blood pressure cuffs. Educators and discharge counselors presented patients with the education and tools needed to engage in self management.

All Native Hawaiian patients were seen by an Advance Practice Registered Nurse (APRN) for education, review of treatment plan, and a definitive plan for out patient follow up. A process for discharge medication reconciliation was developed and physician order sets were changed to insure accurate medication reconciliation, and include pharmacy oversight.

All Native Hawaiian patients that were admitted to QMC from January 2007 through December 2008 became participants in the program. Outcome data for quality core measures, length of stay, 30 day readmission rates, and adverse events following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were reviewed prior to the initiation of the study and compared between the Native Hawaiian patient population and all others for the time period from 12-2006 to 12-2008. Data and technical support were provided by existing staff. The program concentrated on three areas of intervention: Education and self care management, disease management, and stress reduction and wellness.

1. Education and Self-Care Management

Education in cardiac disease management is a key component to promoting quality self care in patients. QHNHHI utilizes an APRN and a clinical pharmacist, both with expertise in cardiology, to educate patients and their families on disease process and self care management. The goal of the education and counseling intervention is to increase the patient's and family's knowledge, enhance their involvement in care, and promote improved compliance with a self care treatment regimen.5–6 The ability to self manage minimizes hospital readmissions, increases quality of life and provides patients with control over their disease process.3 The APRN and clinical pharmacist partner in discharge education and consultation to ensure comprehensive life style education and to ensure accurate reconciliation of home and hospital medications that will promote a successful transition from hospital to home.

The Clinical Pharmacist provides medication information that promotes adherence and helps to prevent medication related adverse events after discharge. A medication schedule is generated for each patient prior to discharge. A pill box is provided for patients with complex medication schedules, significant amounts of medication, and perceived difficulties with medication compliance. The APRN's focus is on the patients understanding of their disease, life style changes required to promote wellness, and stressing the importance of ongoing out patient follow up. Studies have shown that Native Hawaiians do not trust traditional western medicine and are less likely to comply if a trusting relationship is not formed.7 Since forming trust between care provider and patient is imperative to promoting effective communication patient educators use a technique called “talk story” this style of communication is informal and relaxed and allows the patient and care provider to get to know each other and build a therapeutic relationship.3

The QHNHHI team have adapted traditional education strategies to ensure that the material is culturally acceptable. For example, salt reduction is an essential part of dietary education for all cardiac patients. However Pa‘akai (salt) traditionally has spiritual cleansing properties and is highly treasured in the Native Hawaiian culture. Therefore, dietary salt reduction presents a challenge for many Native Hawaiians. Educational material was developed to recognize and appreciate the cultural significance of salt, but also demonstrates the importance of a reduced sodium diet. Culturally sensitive, and disease specific printed materials, have been developed to ensure that the cultural aspects of disease management have been addressed.

Another important concept of culturally sensitive teaching is to include families in the educational process. “Ohana” or family is an integral part of the lives of the Native Hawaiian community and can often be a major component in successful disease management. Families are encouraged to be a part of patients' care and education.

2. Disease Management

Disease management is an integral part of QHNHHI. Heart failure (HF) is among the most common chronic diseases in the United States. It results in frequent hospitalizations with high readmission rates, and complex compliance issues. The literature suggests that heart failure affects minority communities in a disproportionate manner and treatment options that affect outcomes may be influenced by racial or ethnic differences.8

The heart failure population at QMC is made up of approximately 25% Native Hawaiians. Heart failure is a complex cardiometabolic syndrome that is frequently made more difficult to treat because of the high incidence of diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and lung disease. These co-morbidities can also be causative factors in the diagnosis and have a disproportionate incidence in Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander peoples.1–8 Heart failure patients often have frequent hospitalizations with high readmission rates, and complex compliance issues.

The APRN follows the heart failure patients throughout their hospitalization and provides the patients with a scale for daily weights and blood pressure cuffs along with education on the importance of monitoring daily weights, for enhanced fluid management, and blood pressure control. Attending physicians are consulted to ensure that treatment plans are initiated early in the hospitalization, the treatment plan is updated, and quality measures of care are met.

Heart failure patients often have multiple co-morbid conditions such as diabetes and renal failure. These conditions require complex medication schedules, dietary restrictions, and are accompanied by functional impairment and poor adherence to follow up. These factors often contribute to exacerbation of symptoms of heart failure and contribute to frequent readmissions.9 Readmission rates for heart failure that occur in less than 30 days of a previous admission exceed 20% nation wide.10 That number has traditionally been higher for the Native Hawaiian patients than for non-Hawaiians at The Queen's Medical Center. One of the reasons for the higher percentage of Native Hawaiians being readmitted can be attributed to lack of out patient follow-up due to geographic location, transportation, insurance issues and a general mistrust of western medicine. QHNHHI has broken down some of these barriers. While in-patients a trust is developed between the patient and care provider. Part of the APRN's assessment is identifying known barriers to out patient follow-up and putting into place strategies to optimize the chances of follow up occurring. These could include providing services at The Queen Emma Clinic where the same APRN who followed the patient in the hospital, would follow the patient as an out-patient in collaboration with a physician, Social Worker, and Clinical Pharmacist. Heart failure symptoms can be managed, medications adjusted, education reinforced, and housing concerns or insurance issues can be promptly addressed. The multi-disciplinary team addresses the heart failure patients' needs on an on-going basis and readmissions can be prevented.

3. Stress Reduction and Wellness

In March 2008 an integrative care program was implemented that offers wellness education, stress management and complementary healing modalities to Native Hawaiian patients. Services are provided by two holistic APRN's and a licensed massage therapist. In order to promote a healing environment a Ti leaf (La‘i) welcome is offered as well as poi being on the hospital menu. Both La‘i and poi have special meaning for health and healing to Native Hawaiians. On admission to the hospital the holistic APRN conducts a wellness consult, assessing pre-admission levels of psychosocial stress, existing coping mechanisms, patient perception of illness, and life meaning. After the initial evaluation integrative therapies are offered to help manage stress, provide symptom control, relieve anxiety, and improve sleep. These therapies include massage, refl exology, guided imagery, guided meditation, aromatherapy, and Healing Touch.

Music is an essential part of Hawaiian culture. CD's with a variety of music are provided upon patient or family request. A hospital volunteer also visits patients, at their request, to play live ukulele music and sing Hawaiian songs. It has been demonstrated that music lifts the spirits, reduces pain, improves blood pressure, heart rate and calms the nervous system.11–13

Prior to discharge a “wellness prescription” is provided. It offers individualized recommendations which may include sleep hygiene and stress management tips, and other areas of focus for enhanced well being.

Research suggests that Native Hawaiians prefer traditional healing that provides a more holistic approach to care.10 This “whole person” model of care has been shown to enhance patients' overall satisfaction and their willingness to participate in self care management.15 Further evidence suggests that the addition of a holistic approach may reduce readmissions as well as reduce the long term risks of heart disease.14–15

Analysis

The authors used existing data sets to evaluate the process of care (quality of care) among Native Hawaiians (NH) compared with non-Native Hawaiians. Information on outcomes related to percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), heart failure (HF), myocardial infarction (MI), and quality measures were obtained from clinical databases that are maintained by trained nurse coordinators. Utilization, including readmission rates and length of stay were obtained from hospital admission data. Data from 2006, prior to initiation of the QHNHHI were considered as baseline, with data from 2008 considered follow-up or post intervention. Data from 2007, during the planning and initiation of QHNHHI were not evaluated. Changes in measures between 2006 and 2008 were compared among NHand non-NH.

Results

Table 1 displays performance measures (percentages based on the number of eligible patients), readmission rates, and length of stay for NH and non-NH discharged in 2006 and 2008. In general, adherence to performance measures for acute MI and HF were excellent at baseline and generally similar between NH and non-NH. For example both AMI and HF generally ranked above 90% compliance for both groups. An exception is the provision of discharge instructions for HF patients, which was lower for both groups at ∼82%. Consistent with published data, the readmission rate for MI was lower than for HF, with NH having a higher readmission rate than non-NH for HF (33% vs. 23%). Conversely, compared with non-NH, average length of stay for NH was longer for MI and shorter for HF. At follow up, adherence to performance measures improved for both NH and non- NH, achieving>99% for both MI and HF, except for the provision of discharge instructions which, nonetheless, improved to 88%–89%.

Table 1.

Performance Measures, 30-day Readmission Rates and Length of Stay: 2006 vs. 2008

| Baseline: 2006* | Follow-up: 2008* | |||

| Acute MI | NH | Non NH | NH | Non NH |

| Aspirin at Arrival | 92% | 97% | 99% | 100% |

| Aspirin at discharge | 98% | 96% | 100% | 99% |

| Ace-Inhibitor for LVSD | 94% | 86% | 100% | 100% |

| Smoking Cessation | 95% | 95% | 100% | 100% |

| Beta blocker at discharge | 100% | 98% | 99% | 99% |

| Beta blocker at admission | 100% | 98% | 100% | 99% |

| 30 Day Readmit Rate | 12% | 13% | 10% | 9% |

| Average LOS | 9.10 days | 7.81 days | 7.41days | 6.66 days |

| Heart Failure | ||||

| Discharge instructions | 82% | 83% | 89% | 88% |

| LV Function | 95% | 94% | 99% | 100% |

| Ace-Inhibitor | 92% | 88% | 100% | 100% |

| Smoking Cessation | 94% | 98% | 100% | 100% |

| 30 Day Readmission Rate | 33% | 23% | 17% | 19% |

| Average LOS | 6.8 days | 7.6 days | 7.8 days | 7.7 days |

NH = Native Hawaiian; MI: Myocardial infarction; LVSD: Left ventricular systolic dysfunction; LOS: Length of stay; LV: Left ventricular

Percentages are based on number of eligible patients.

Quality Core Measures have shown improvement in both groups during the time of the study. There are several unrelated factors that have contributed to these outcomes. There have been changes made to physician order sets and discharge instructions that promote compliance with core measures. Adherence to core measure compliance is monitored by the staff of the Center for Outcomes and Research and the cardiac APRN's diligently document contra indications to core measure quality indicators.

NH patients underwent 68 percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in 2006 and 69 in 2008. The number of periprocedural myocardial infarctions, renal failure, emergent/urgent coronary bypass surgery, and death substantially improved between baseline and follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adverse events following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) among Native Hawaiians: 2006 vs. 2008

Discussion

In general, we found that the quality of cardiovascular care of NH at QMC was excellent at baseline. The quality core measures have improved among the entire patient population following the implementation of a multi-disciplinary team. Some improvements in quality core measures were notable among the NH population. The less than 30 day readmission rates for NH with acute myocardial infarction have been reduced by 2% and NH heart failure patients with less than 30 day readmissions have decreased from 33% to 17%. The national average for HF readmissions in the United States is 19% to 21%.

The length of stay (LOS) for patients following an acute myocardial infarction has decreased slightly, and the LOS for heart failure patients remains unchanged. The length of stay continues to be of concern and the NH population has the largest room for improvement. The extended LOS in this patient population may be related to the severity of illness at the time of admission.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, this study was observational and not randomized. The QHNHHI intervention was implemented in the setting of ongoing, long-standing performance improvement programs, and the impact of the intervention cannot be clearly determined. For example, the implementation of computer- based order sets and physician report cards likely improved adherence to performance measures and resource utilization. Second, the overall adherence to performance measures and resource utilization was high for both the NH and non NH. The difference between the two groups was less than expected, which may have limited the potential impact of the intervention (ceiling effect). Nonetheless, improvements between baseline and follow up indicate that the results may be clinically meaningful.

In summary, the authors have found that the quality of care among NH and non-NH hospitalized with MI and HF is excellent. The implementation of a multidisciplinary, patient centered intervention, focused on reducing disparities in cardiovascular disease, when added to an ongoing performance program, can have a positive impact on quality of care, patient satisfaction, and promotes the reduction of health care disparities for all Hawaiian People.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Dr. Gerard Akaka, VP Medical Affairs, Cathy Young, VP Cardiac/Geriatric, and Diane Paloma, Director Native Hawaiian Health Program for administrative support. We would like to thank Suzanne Beauvallet, Clinical Data Base Coordinator, and Desiree Uehara, Clinical Data Analyst for taking the time to provide us with outcomes data. Finally we wish to express our deep appreciation to Dr. Todd Seto, Medical Director of the Center for Outcomes Research for his support, his invaluable input, and his precious time during this process.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Yancy Clyde W. the Prevention of heart failure in minority communities and discrepancies in health care delivery systems. The Med Clin N Am. 2004;88:1347–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mau MK, Sinclair K, Saito EP, Baumhofer KN, Kaholokula JK. Cardiometabolic health disparities in native Hawaiians and other pacific islanders. Epidemiologic Reviews. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp004. “in press”. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaholokula JK, Saito E, Mau MK, Latimer R, Seto TB. Pacific islanders' perspective on heart failure management. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;70:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenheimer T, MacGregor K, Shafiri C. Helping patients manage chronic conditions. [July 14, 2009]. http:www.chcf.org/topics/chronicdisease.

- 5.Jerant AF, von Frederichs-Fitzwater MM, Moore Monique. Patients' perceived barriers to active selfmanagement of chronic conditions. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;75:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mau MK, West M, Sugihara J, Kamaka M, Mikami J, Cheng SF. Renal disease disparities in asian and pacific-based populations in Hawai'i. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2003;95(10):955–963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown DW, Haldeman GA, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Racial or ethnic differences in hospitalization for heart failure among elderly adults: medicare, 1990 to 2000. American Heart Journal. 2005;150:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trail. JAGS. 2004;52(675):676–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hospital bedside technology solution results in 74 percent reduction in heart failure readmission rate. 2009. Jul 21, http.//www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/

- 10.Young N, Braun K. La'au lapa'au and westeren medicine in Hawai‘i: experiences and perspectives of patients who use both. Hawaii Med J. 2007;(66):176–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsson U. the Effects of music intervention in stress response to cardiac surgery in a randomized clinical trail. Heart Lung. 2009;38(3):201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebneshahidi A, Moheseni M. the Effect of patient selected music on early postoperative pain, anxiety, and hemodynamic profile in cesarean section surgery. Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(7):827–831. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan MF, Wong OC, Chan HL, et al. Effects of music on patients undergoing a c-clamp procedure after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(6):669–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]