Abstract

Intravenous vascular access is technically challenging in the adult mouse and even more challenging in neonatal mice. The authors describe the technique of retro-orbital injection of the venous sinus in the adult and neonatal mouse. This technique is a useful alternative to tail vein injection for the administration of non-tumorigenic compounds. The authors report that they have routinely used this technique in the adult mouse to administer volumes up to 150 µl without incident. Administration of retro-orbital injections is more challenging in neonatal mice but can reliably deliver volumes up to 10 µl.

For intravascular delivery of agents to the adult mouse, personnel typically use the lateral tail veins1. This procedure is technically challenging and often has a high rate of failure. In preparation for tail vein venipuncture, the mouse is often placed under a heat lamp to promote peripheral vasodilation and is then mechanically restrained1. In our opinion, this approach can cause distress in the animals, especially if the initial venipuncture is unsuccessful and repeated attempts are made.

Intravenous injections in the neonatal mouse are even more challenging. Percutaneous injection of the superficial temporal vein has been described2,3, but this method has several disadvantages. First, it requires two people3. Second, owing to increased pigmentation and skin thickness in older neonates, it might not be useful for mice that are older than 4 d (ref. 3). Third, it is technically challenging.

Retro-orbital injections may seem aesthetically distasteful, but we argue that this easily mastered technique is ultimately more humane than alternative intravascular injection techniques in mice. We routinely use this method for bone marrow transplantation4, leukemia induction5, administration of experimental compounds6 and gene therapy7. Although researchers have reported using this technique on both neonatal and adult mice8–11, we have not found a thorough description of the use of this technique in adults and neonates in the literature. Here we describe our technique for retro-orbital injections in adult and neonatal mice.

The procedures described below were approved by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) ACUC. These procedures were carried out in a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals12.

ADULT MOUSE INJECTION TECHNIQUE

We prepare the syringes first. We prefer to use a 27.5-gauge (or smaller), 0.5-in insulin needle and syringe (e.g., Terumo U-100, Terumo Medical Corporation, Elkton, MD). A tuberculin syringe with a 27-gauge (or smaller), 0.5-in hypodermic needle can also be used. When using a tuberculin syringe, a large volume (50–70 µl; ref. 13) of the injectate is lost in the dead space of the syringe hub and needle, which is important to keep in mind if the injectate is valuable. We recommend that injectate volumes not exceed 150 µl.

Because the needle is being placed in the retro-bulbar space (the region behind the globe of the eye) the mouse should be anesthetized so that it remains still during the procedure. We prefer to use an inhalant anesthetic, because of its rapid induction and recovery times. We place the mouse in a plexiglas chamber and use isoflurane to induce anesthesia. The size of the plexiglas chamber we use varies depending on the procedure space being used. We sometimes use a plexiglas chamber that is 10 in wide × 4 in high × 4.5 in deep (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA).

We then place a funnel-shaped nose cone connected to a non-rebreathing apparatus (Surgivet, Dublin, OH) on the anesthetized mouse. We use a down-draft table or a charcoal scavenging device to manage waste anesthetic gases and decrease exposure of personnel to the gases. A down-draft table pulls the inhalant gas away, whereas a charcoal scavenging device absorbs the gas. To decrease the likelihood of the mouse developing hypothermia, the mouse can be placed on a warming device, such as a disposable hand warmer (Grabber Warmer, Grabber Inc., Grand Rapids, MI; Fig. 1). Because the surface temperature of the hand warmer can approach 130–150 °F, the warming device should be covered with a protective layer of paper toweling or gauze to prevent thermal injury to the mouse.

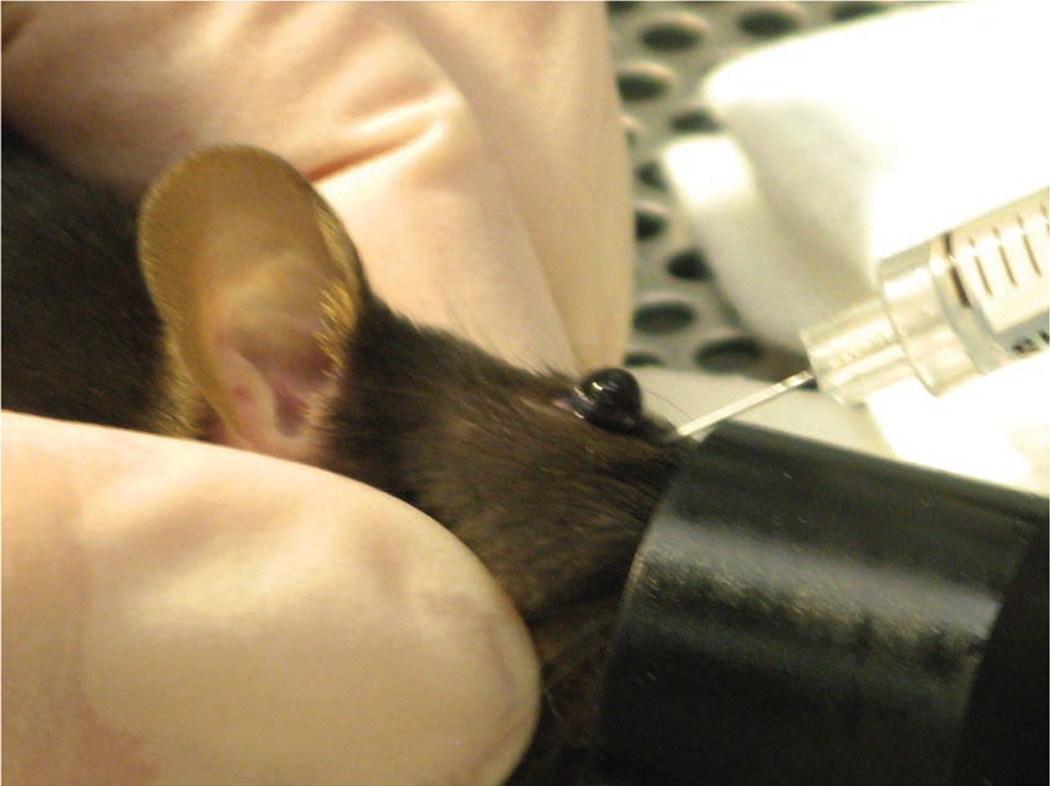

FIGURE 1.

An anesthetized adult mouse placed on a protected warming device. A funnel-shaped face mask is attached to the non-rebreathing apparatus. A down-draft table is used to capture waste anesthetic gases.

A right-handed operator will probably find it easiest to administer the injection into the right retro-orbital sinus of the mouse. The mouse is placed in left lateral recumbency with its head facing to the right. The operator then partially protrudes the mouse’s right eyeball from the eye socket by applying gentle pressure to the skin dorsal and ventral to the eye (Fig. 2). Both the trachea and the ventral cervical (neck) vessels (the jugular veins and carotid arteries) run along the ventral cervical area. The veins drain the head area and the arteries supply this area. Care must be taken not to apply excessive pressure to the ventral cervical vessels, because this could impede blood flow and impede the injection. It is also important not to apply pressure to the trachea, because this could cause the trachea to collapse, thereby stopping the mouse from being able to breathe.

FIGURE 2.

The mouse’s eye is partially protruded from the socket by applying gentle downward pressure to the skin dorsal and ventral to the eye.

In addition to using the inhalant anesthetic, we also place a drop of ophthalmic anesthetic (0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution, Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX) on the eye that will receive the injection (Fig. 3). This provides additional procedural and post-procedural analgesia. While being careful not to scratch the cornea, the operator can remove excess ophthalmic anesthetic by holding an absorbent gauze pad to the medial canthus. The needle is carefully introduced, bevel down, at an angle of approximately 30°, into the medial canthus (Fig. 4). Most injections are carried out with the bevel of the needle facing up, but for retro-orbital injections, placing the needle so the bevel faces down decreases the likelihood of damaging the eyeball. The operator uses the needle to follow the edge of the eyeball down until the needle tip is at the base of the eye (Fig. 5). The operator then slowly and smoothly injects the injectate. We do not aspirate before injection. Once the injection is complete, the needle is slowly and smoothly withdrawn. We believe that slowly withdrawing the needle gives the injectate a brief moment to redistribute so that the injectate does not follow the needle path out. There should be little or no bleeding.

FIGURE 3.

The operator places a drop of topical ophthalmic anesthetic on the eye of the mouse before carrying out the injection.

FIGURE 4.

The operator inserts the needle, bevel down, at the medial canthus, into the retro-orbital sinus.

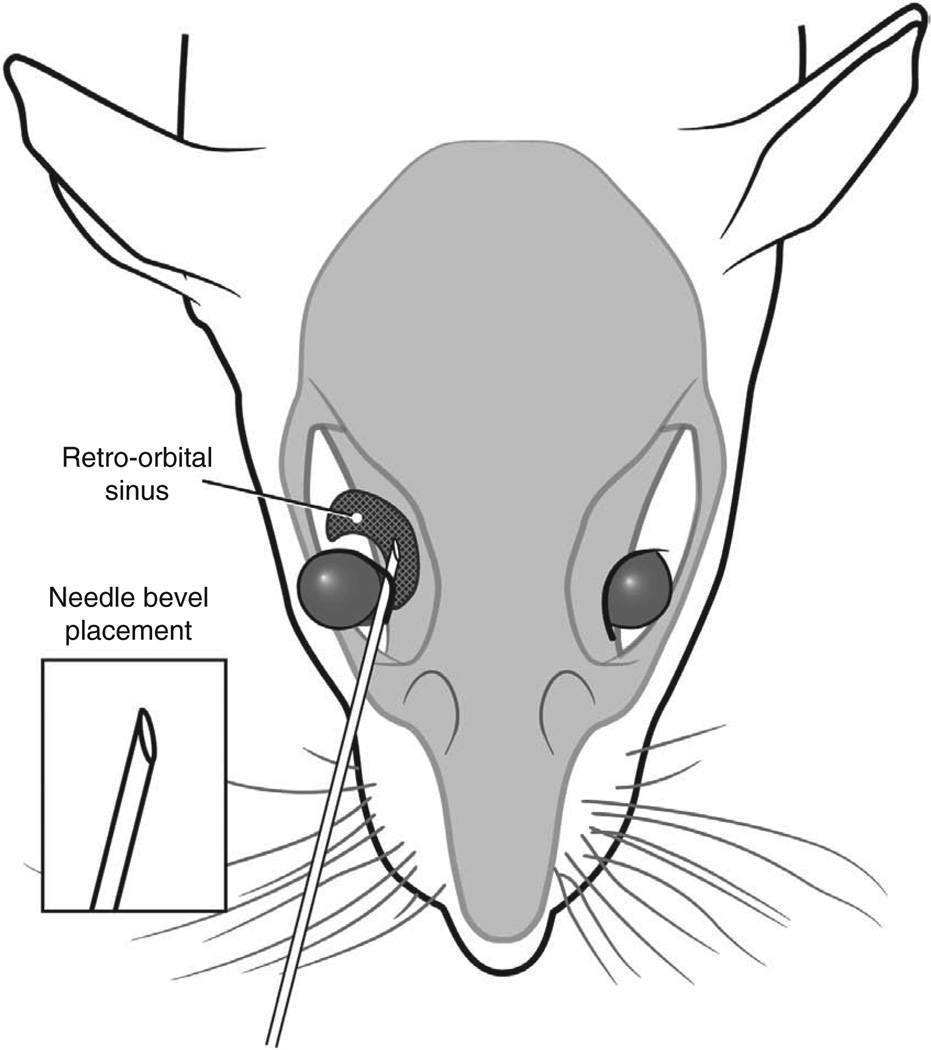

FIGURE 5.

Correct placement of the needle relative to the retro-orbital sinus, the eyeball and the back of the orbit. Illustration by Darryl Leja.

After the injection is complete, the mouse is placed back into its cage for recovery. A protected warming device can be placed in the cage, but this is usually not necessary because the injection procedure takes only a short time (it takes about 1 min to induce anesthesia and the injection itself takes less than 15 s) and the mouse is usually ambulatory within 30–45 s.

NEONATAL MOUSE INJECTION TECHNIQUE

We use this technique for injecting substances into mouse pups that are 1–2 d old. First, we place all of the pups from a litter into a small container in which we have made a ‘nest’ that includes a protected warming device and soft gauze (Nu Gauze, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) and then cover the mice with an additional gauze pad to provide added warmth. As long as the pups are kept warm, any sort of container or cage can be used. We typically use 16-ounce vented hot food containers (Solo Cup Co., Lake Forest, IL). We prepare a second ‘nest’ to place the pups in after they have received the injections. We leave the mother in her cage in the animal holding room and carry out the injections in a procedure room. This way, the mother is not exposed to the potentially distressing audible and ultrasonic vocalizations that the pups may emit during restraint and administration of injections.

To administer retro-orbital injections in pups, we use a 31-gauge, 0.3125-in needle attached to a 0.3-ml insulin syringe (BD Ultra-Fine II, Becton, Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ). We do not inject more than 10 µl of liquid. The pups are not anesthetized for this procedure, because they can be adequately manually restrained without being anesthetized.

To carry out the injections, we use a dissecting microscope (8–10× magnification is usually sufficient). We also place a light source, such as a ringlight or a fiber optic point-source light, above the procedure area. Depending on which procedure space we are using, we use different types of dissecting microscopes and light sources. We sometimes use a Nikon SMZ-U dissecting microscope (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, NY). We use a Crescent 150 fiber optic light source (Nikon Instruments, Inc.) and a NCL 150 ringlight (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), among other types of light sources. To provide additional warmth for the mice, we turn on the stage light in the microscope and cover it with a gauze pad. For neonatal mice, like adult mice, a right-handed operator will find it easiest to place the pup in left lateral recumbency, with its head facing to the right, and administer the injection into the right retro-orbital sinus. The pup’s head is gently restrained with the tip of the thumb and forefinger (Fig. 6). The operator must be careful not to place pressure on the trachea or impede venous flow. The rest of the pup’s body is nestled between the thumb and forefinger. In our experience, once the mouse is comfortably restrained, there is little struggling and the mouse does not emit audible vocalizations (we have not tried to record ultrasonic vocalizations).

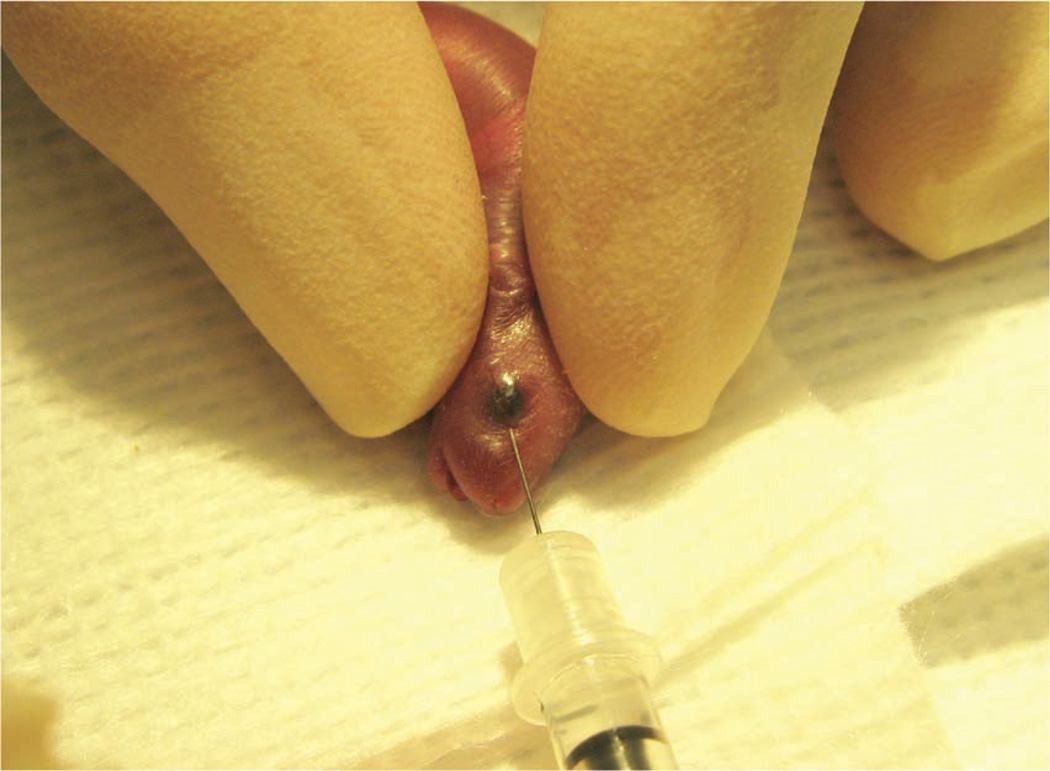

FIGURE 6.

The operator gently restrains the pup between his or her thumb and forefinger.

The operator uses sterile saline and a cotton-tipped applicator to gently clean the area above the eye. This helps to remove any skin flakes that may get in the way of the injection and helps to make the skin slightly more transparent. Care must be taken not to overly wet the pup, because this could increase the risk of hypothermia. We do not use alcohol or a topical ophthalmic anesthetic. The ophthalmic anesthetic will not penetrate the skin, and we think that alcohol might irritate the pup’s facial skin. The operator then inserts the needle, bevel down, at the ‘3 o’clock’ position into the eye socket (the area that will become the medial canthus) at an angle of approximately 30° (Fig. 7). The operator mentally visualizes the back of the socket and advances the needle to the area of the retro-orbital sinus. The injection is made in a gentle, smooth, fluid motion. If the injection is successful, the operator might observe blanching of the superficial temporal vein, but this does not always occur. Regardless of whether blanching is noted, we have seen the injectate in the target organs7. The needle should be withdrawn slowly, allowing a brief moment for the injectate to redistribute. We sometimes see a small drop of blood at the injection site, which can be gently cleaned with a cotton-tipped applicator. The operator then places the pup in the second prepared nest. When all the pups in a group have received injections, the pups are checked for any additional bleeding and cleaned, if necessary. We then return the pups to their mother in the home cage.

FIGURE 7.

The operator inserts the needle, bevel down, at a 30° angle in the area that will become the medial canthus.

RETRO-ORBITAL SINUS MORPHOLOGY

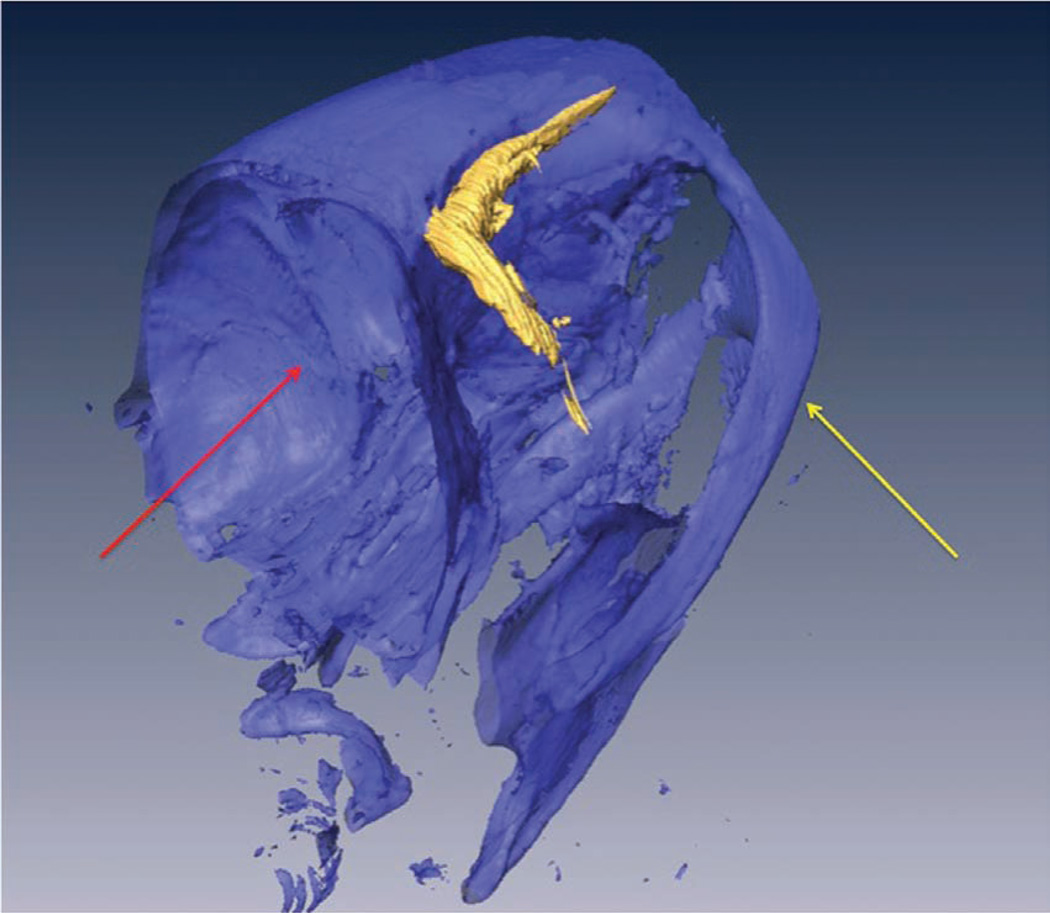

An exact description of the retro-orbital sinus of the mouse seems to be lacking in the literature, but it may be best described as a confluence, pool or sinus of several vessels, likely including the supraorbital vein, inferior palpebral vein, dorsal nasal vein and the superficial temporal veins (Fig. 8; refs. 14,15). We have been able to visualize the retro-orbital sinus area as a large area with a substantial amount of blood flow (Fig. 9) by using X-ray computed tomography (CT; SkyScan 1172 MicroCT; SkyScan, Kontich, Belgium) and an intravascular X-ray CT contrast agent (Fenestra VC; ART Advanced Research Technologies, Inc., Montreal, Canada). We acquired the CT data with an accelerating voltage of 51 kV, a 0.5-mm aluminum filter and a true three-dimensional image resolution of 6.5 µm.

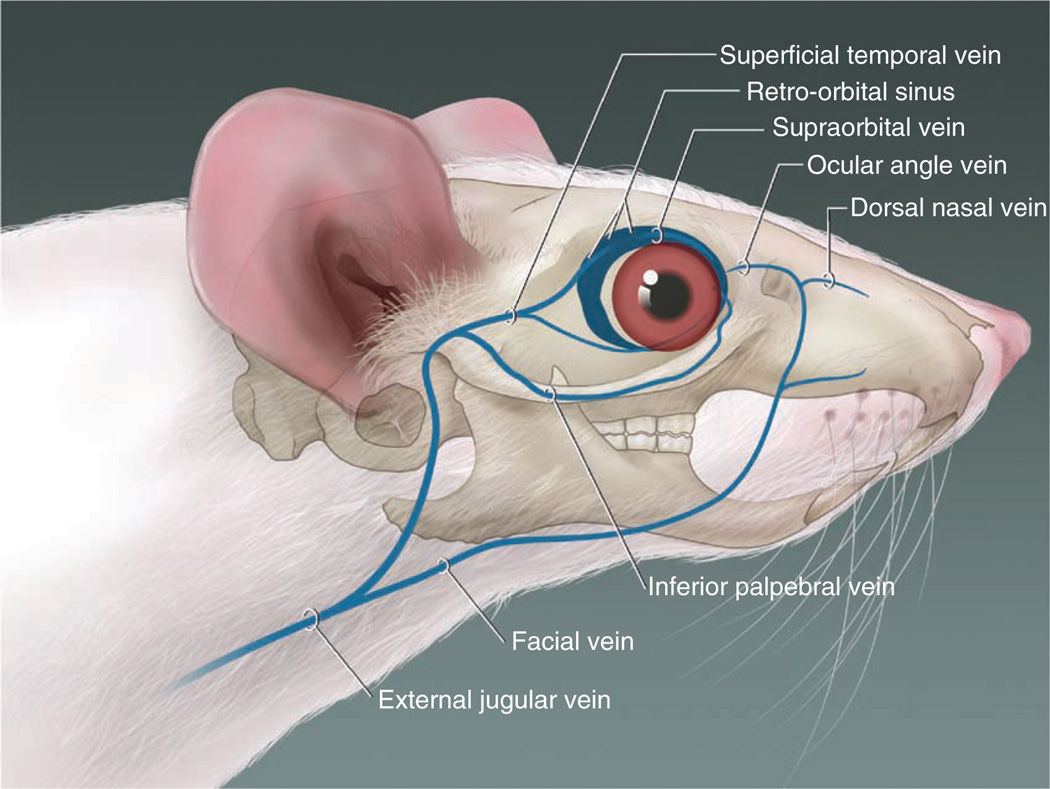

FIGURE 8.

The blood vessels contributing to the retro-orbital sinus of the mouse. Illustration by Darryl Leja.

FIGURE 9.

A volume-rendered three-dimensional computed tomography scan of the head of a mouse (facing right) that received a retro-orbital injection of an intravascular contrast agent. The retro-orbital sinus is in high contrast (shown in gold). The underlying bone structures are selected out with a bone-window (shown in blue) as a structural reference. The yellow arrow points to the zygomatic arch. The red arrow points to the cranial vault.

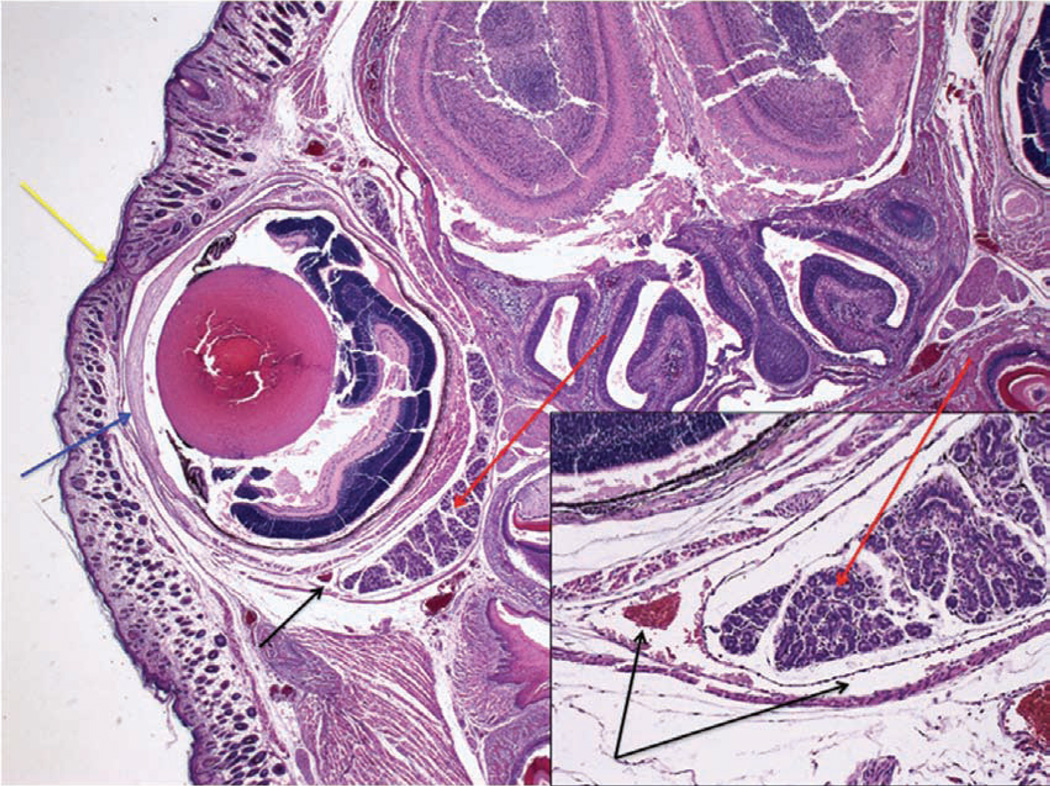

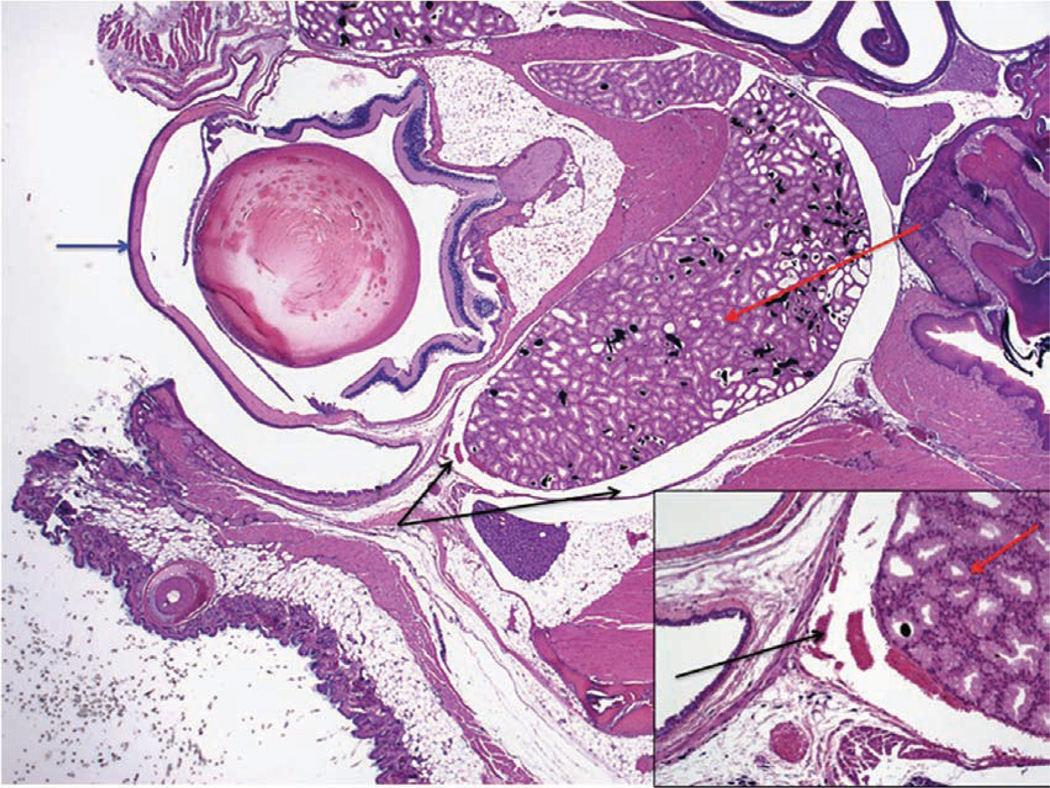

To assess the accuracy of the injections, we have collected post-mortem histological samples from neonates (Fig. 10) and adults (Fig. 11) at 30 min and 7 d after these mice received retro-orbital injections. We have observed some leakage of the injectate from and around the sinus. However, the various experiments in which we use this technique have reported 100% success in adults and neonates. This indicates that the injectate reached its target site 100% of the time. We say that we have achieved 100% success because we see the expected outcome (for example, leukemia develops when we inject leukemic cells) 100% of the time.

FIGURE 10.

Section through the right eye and surrounding tissue of a 1-d-old mouse pup 30 min after administration of a retro-orbital injection (12.5× magnification; hematoxylin and eosin staining). The inset shows the injected retro-orbital sinus (100× magnification). The retro-orbital sinus (black arrows) and surrounding tissue appear normal. Red arrows point to the Harderian gland. Blue arrow points to the corneal surface of the eyeball. Yellow arrow points to the fused eyelids.

FIGURE 11.

Section through the right eye and surrounding tissue of an adult mouse 30 min after administration of a retro-orbital injection (12.5× magnification; hematoxylin and eosin staining). The inset shows the injected retro-orbital sinus (100× magnification). The retro-orbital sinus (black arrows) and surrounding tissue appear normal. Red arrows point to the Harderian gland. Blue arrow points to the corneal surface of the eyeball.

DISCUSSION

Researchers have published studies comparing the effectiveness of retro-orbital injections and tail vein injections in adult mice10,11. These reviews have shown that the two routes can be used interchangeably and that both routes are equally effective10,11. Retro-orbital injections in neonates have also been mentioned8,9 but, to our knowledge, not described in detail.

We think that retro-orbital injection is an easy and reliable method for intravascular delivery of many agents. We have used this method to inject substances into hundreds of adult mice, without incident. We have also used this method to administer intra-orbital injections in more than 50 litters (more than 400 pups (1–2 d old)) with complications rarely observed. Occasionally, we have noted a temporary paleness or cyanosis in a pup that has received an injection, which we attribute to a combination of the restraint and the injection itself. These side effects could perhaps be lessened or alleviated by warming the injectate to body temperature instead of administering the injectate at room temperature. We have never observed this phenomenon in adults, in which we routinely inject compounds at room temperature. We also occasionally inject compounds into adult mice that must be maintained on ice until just before the injection. We allow these to warm up only briefly before we inject them. We have not experienced any problems with maternal rejection of any pup that has received a retro-orbital injection. This could be due to the precautions we take in separating the mothers from their pups before the injections or to the good maternal abilities of the particular dams.

As with any intravenous route, injection volume is limited. Although researchers have described administering intravenous injection volumes of 200–300 µl for adults16,17, we think that injectate volumes should not exceed 150 µl for adults. In an ‘average’ 30-g mouse, the estimated blood volume is approximately 2.2 ml (7.2% of the body weight16). An injection volume of 200–300 µl, even if given slowly, may result in temporary vascular overload. A newborn mouse pup weighs approximately 1–1.5 g. Even though neonates have slightly higher blood volume per unit of body weight than do adult mice18, the circulating blood volume in a neonatal mouse probably does not exceed 0.08 ml (80 µl). In light of this and the very small retro-orbital space in a pup, we feel that a maximum injection volume of 10 µl in the neonate is reasonable.

Post-mortem histological samples from neonates (Fig. 10) and adults (Fig. 11) that received retro-orbital injections showed normal morphology of the injected sinus and surrounding tissue. Because there can be leakage of the injectate from and around the sinus, retro-orbital injection might not be an acceptable route by which to carry out solid tumor transplantation. If the retro-orbital route is used for injecting cell suspensions, only single-cell suspensions can be used. Personnel can make a one-cell suspension by using a 70-µm cell strainer (BD Falcon, BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) to filter the suspension before using it. Failure to filter cell suspensions could lead to obstruction of vessels supplying critical organs and subsequent death of the animal.

Although we believe that retro-orbital injection is an easy and reliable method for intravascular delivery of various compounds in mice, a novice operator must receive sufficient training on cadavers and terminally anesthetized mice before using the technique in live mice. For initial training, we recommend administering injections of dyes (e.g., India ink, new methylene blue) or microbeads (6-µm Polybead, Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA) that are approximately the size of a mouse red blood cell, because these allow the novice to see the location of the injection.

In conclusion, retro-orbital sinus injection of both neonatal and adult mice is a useful method for intravascular delivery of many agents. In the hands of a skilled operator, the incidence of complications is rare and distress to the animal is minimized. We believe this is a useful alternative method for intravascular administration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Brenda Klaunberg and Danielle Donahue from the NIH Mouse Imaging Facility and Darryl Leja from the NHGRI Intramural Publication Support Office for their assistance with this project. This work was carried out in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a PhD degree for T.Y. (Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel). This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NHGRI, the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Suckow MA, Danneman P, Brayton C. In: The Laboratory Mouse. Suckow MA, editor. Roca Raton, FL: CRC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billingham RE, Brent L. Acquired tolerance of foreign cells in newborn animals. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1956;146:78–90. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1956.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sands MS, Barker JE. Percutaneous intravenous injection in neonatal mice. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1999;49:328–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannons JL, et al. Optimal germinal center responses require a multistage T cell:B cell adhesion process involving integrins, SLAM-associated protein, and CD84. Immunity. 2010;32:253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyde RK, et al. Cbfb/Runx1 repression-independent blockage of differentiation and accumulation of Csf2rb-expressing cells by Cbfb-MYH11. Blood. 2010;115:1433–1443. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song H, et al. Mammalian Mst1 and Mst2 kinases play essential roles in organ size control and tumor suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:1431–1436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911409107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yardeni T, et al. A non-viral, GNE-Lipoplex treatment to correct sialylation defects in Gne-mutant (M712T) mice American Society of Gene Cell Therapeutics 2010 Annual Meeting; Washington, DC. Abstract #144. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerbtsova M, Liu XH, Ye X, Ray PE. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to glomerular cells in newborn mice. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2005;20:1395–1400. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1882-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jerbtsova M, Ye X, Ray PE. A simple technique to establish a long-term adenovirus mediated gene transfer to the heart of newborn mice. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2009;9:136–140. doi: 10.2174/187152909788488645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price JE, Barth RF, Johnson CW, Staubus AE. Injection of cells and monoclonal antibodies into mice: comparison of tail vein and retroorbital routes. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1984;177:347–353. doi: 10.3181/00379727-177-41955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steel CW, Stephens AL, Hahto SM, Singletary SJ, Ciavarra RP. Comparison of the lateral tail vein and the retro-orbital venous sinus as routes of intravenous drug delivery in a transgenic mouse model. Lab Anim. (NY) 2008;37:26–32. doi: 10.1038/laban0108-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhambhani V, Beri RS, Puliyel JM. Inadvertent overdosing of neonates as a result of the dead space of the syringe hub and needle. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal. Ed. 2005;90:F444–F445. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.070045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook MJ. The Anatomy of the Laboratory Mouse. New York: Academic; 1965. pp. 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timm KI. Orbital venous anatomy of the rat. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1979;29:636–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox JG, et al., editors. The Mouse in Biomedical Research. 2nd edn. vol. III. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauck L, Bihun C. Basic anatomy, physiology, husbandry, and clinical techniques. In: Hillyer EV, Quesenberry KE, editors. Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 1997. p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain NC, editor. Veterinary Hematology. 4th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lee & Febiger; 1986. [Google Scholar]