Abstract

Background

The practice of traditional bone setting (TBS) is extensive in Nigeria and it enjoys enormous patronage by the populace. However, the outcome of the intervention of TBS treatment is usually poor with profound effects on the patient. There are many publications highlighting different aspects of this subject but none has summarized the entire practice and problems as a single publication.

Objective

This work aims at reviewing the entire subject of traditional bone setting in Nigeria in a single article to enable easy understanding and appreciation of the practice and problems of traditional bone setting by orthodox practitioners.

Method

A total of thirty-one relevant published original scientific research papers involving all aspects of the subject were reviewed and the practices and problems were documented.

Results

The results showed that the origin of the practice is shrouded in mystery but passed on by practitioners from one generation to another. There is no formal training of bonesetters. Though the methods of treatment vary, the problems caused by them are usually similar with extremity gangrene being the worst. When attempts have been made to train the bone setters, improvement have been noted in their performance.

Conclusion

In other to prevent some of the most debilitating outcomes like amputation, it is suggested that the TBS practitioners undergo some training from orthopaedic practitioners.

Keywords: traditional bone setting, Nigeria, practice

Introduction

In many developing countries, the traditional care of diseases and afflictions remain popular despite civilization and the existence of modern health care services.1,2 In Nigeria, the traditional bone setters perhaps more than any other group of traditional care-givers enjoy high patronage and confidence by the society2,3. Indeed, the patrons of this service cuts across every strata of the society including the educated and the rich2. Many reasons account for this including the belief that diseases and accidents have spiritual components that need to be tackled along with treatment2. The age of their clients vary from the newborn with musculoskeletal deformity to the very elderly with fractures4 The commonest problems treated by them are fractures and dislocations 4,5,6,7,8,9,10. The practice is wide-spread in Nigeria including areas well served with healthcare facilities such as Lagos, Ibadan and Enugu3,4. Unfortunately, however, the outcome of their intervention in trauma care frequently leads to loss of limbs, lifelong deformities and sometimes death. A thorough study of this practice is therefore an issue of public health importance.

Methods

A literature search of relevant published articles in standard recognized scientific journals was done by the authors including publications from all regions of Nigeria and other countries. A search of PubMed and AJOL was also done using search terms - bone setter, traditional bone setters and traditional bone setting in Nigeria. Cross references of the articles which did not appear in PubMed were also reviewed. Thirty-one articles detailing the following areas which were considered most relevant by the authors were reviewed and analysed.

History/training methodology

Reasons for patronage

Different methods of treatment

Problems/complications.

Results

History/Training Methodology

Virtually all the reviewed publications agreed that this method had existed for decades 1,2,3,4 and indeed clusters of family and tribes practice it and practitioners keep it as a family secret. The training is passed from one generation to another through skills and experience acquired as part of an ancestral heritage 1,3,5. However, there are no scientific inquisitions and there is no peer review of the results obtained. The training is also not formal and not structured. There is no certification and anyone can actually claim to be a practitioner particularly in the big cities.

Reasons for Patronage

Several of the studies identified the following as reasons for the patronage of TBS:

Methods used in treatment

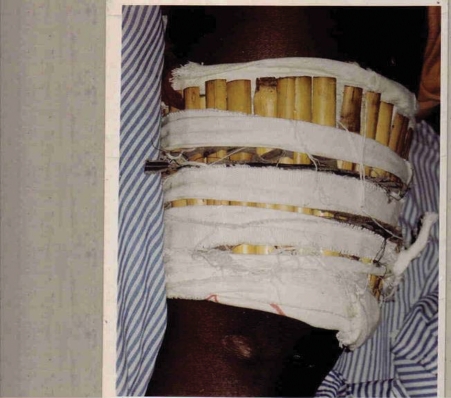

The different methods used in Nigeria are: Use of splints and bamboo stick 4 or rattan cane or palm leaf axis3 with cotton thread or old cloth. This is rapped tightly on the injured part and left in place for the first 2–3 days before intermittent release and possible treatment with herbs and massage 3,4. This release of the splint is however not uniformly practiced.

Massage and manual traction of the affected bone. This may be done exclusively or in conjunction with the use of traditional splint and herbs application. Fractures that fail to heal with the routine treatment of splinting and massaging may be given further traditional treatment by way of scarifications, sacrifices and incantations 3,4.

Some recent reports from South-Western and Central Nigeria confirm that some of the practitioners have started inculcating some orthodox practices into their treatment albeit wrongly. This includes wound dressing and suturing 12 and even use of radiological aids13.

Limitations

The problems identified in the literature have no regional variation in Nigeria. All documentations reviewed, agreed that the commonest cause of extremity gangrene in musculoskeletal injuries is the intervention in management by the TBS14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Other complications frequently seen include chronic osteomylitis, non-union, malunion, joint stiffness, chronic joint dislocations, Volkmann ischaemia, sepsis and tetanus 4,6,7,8,24,25. In addition some of practitioners actually come to orthodox centres to canvass and take away patients posing as relations.

Discussion

In Nigeria, about 85% of patients with fractures present first to traditional bone setters27. It is therefore of public health importance that the practice of this discipline be well understood.

One of the most important flaws of the practice of the TBS presently in Nigeria is the process of training and acquiring skills in bone setting, which is not formal, undocumented and uncontrolled with attendant continuous decline in imparted knowledge and hoarding of information2,3,4,12,14.

Furthermore, the practice is passed on by oral tradition and there is no regulation, review and even peer-criticism. Quality is therefore not guaranteed and complications are high27. This is unlike orthodox training, which is regulated, open and subject to regular review on the basis of new evidences. In China, Chinese and Western care had existed together for decades28, indeed by 1949 there were about 500,000 Chinese-style doctors trained in care of diseases including pain control, fracture and sprains management. The practice is regulated and practitioners undergo structured training.25 In view of the lack of structured training for TBS in Nigeria, it is therefore not surprising that the practice is associated with so many problems, which include the process of establishment of diagnosis that is shrouded in mystery 12,14 and a notorious inability to identify cases beyond their ability and consequent non-existence of a referral system. Usually, following failure of a bone setter, the patient usually will voluntarily discharge himself/herself to another bone setter13 or to the hospital. This infact is also unlike what happens in Turkey, where the practitioners usually refer difficult cases.26

In recognition of this deficiencies therefore, some authors have advocated a formal training for the TBS and their incorporation into the primary care system in Nigeria27. This idea is worth trying as training programmes targeted at the bone setters in Nigeria and other countries have been known to had to an improvement in their performance and a reduction in complications.26,28,30,31

Though patronage of the TBS is influenced by quite a number of factors, a major reason is the perceived cheaper fees28. However, this has been better characterized to be that multiple little payments are allowed by bonesetters and even payment in kind with clothes and life animals2,27. Other reasons include the wide belief in our community that sickness and afflictions usually have spiritual aspects that need to be cured with traditional means like the use of incantations and concortions2,27. Furthermore, in Nigeria strong social and family ties still exist. Friends and family are therefore an important group in the choice of the type of treatment and injured or sick relative will receive28. However, there are some valid reasons for patronage of the TBS and these include easy accessibility and quick service 2,3 rendered by the TBS compared to hospitals where there are protocols and queues before patients can be seen. Indeed, in a number of communities especially in Northern Nigeria and to some extent in Southern Nigeria, orthodox centers are several hundreds of kilometers away. It is important to state that the patronage of traditional treatment in Nigeria is independent of educational status and religious belief29

The treatment methods are essentially similar with minor variations depending on family and community practice 3,4,13. The complication of treatment is usually a function of the method applied. Where splints have been applied, compartment syndrome, extremity gangrene and Volkmann ischaemia are known and regularly occurring complications 4,7,8 and where massaging and pulling are the preferred treatment option, they usually lead to hetrotophic ossification and non-union and scarifications have been known to lead to chronic osteomylitis, sepsis and tetanus. These problems however will continue to exist except urgent steps are taken to regulate the present practice of the trade in Nigeria. Successes, which have been, acknowledged by some authors 3, are few with majority of authors agreeing that the practice is dangerous as presently practiced28,29,30,31.

Though the practice in Nigeria is similar in many respects to what obtains in other countries6,26,31, an important difference is the total absence of referral in the practice of the practitioners in nigeria28, lack of any form of structured training26 and the near impunity with which they practice their trade28.

Conclusion

In view of the societal confidence, which the TBS enjoy in Nigeria, it is important that efforts be made at regulating their practice including the establishment of a sound referral system and adoption of a standard training curriculum. Though a number of deficiencies of the bone setters have been highlighted in this paper, it is obvious that they can be trained to function at the primary level especially in the rural areas.

Figure 1.

Traditional splint

Figure 2.

Another Traditional Splint

References

- 1.Orjioke CJG. Does traditional medicine have a place in Primary Health Care? Orient J of Medicine. 1995;7(1and2):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thanni LOA. Factors influencing patronage of traditional bonesetters. WAJM. 2000;19(3):220–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oginni LM. The use of Traditional fracture splint for bone setting. Nig Medical Practitioner. 1992;24(3):49–51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onuminya JE, Onabowale BO, Obekpa PO, Ihezue CH. Traditional Bonesetter's Gangrene. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 1999;23:111–112. doi: 10.1007/s002640050320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onuminya JE. The role of the traditional bone setter in Primary fracture care in Nigeria. S Afr Med J. 2004 Aug;94(80):652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agaja SB. Prevalence of limb amputation and role of TBS in Nigeria. Nig J surgery. 2000;7(2):79. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ofiaeli RO. Complication of methods of fracture treatment used by traditional healers a report of 3 cases necessitating amputation at Ihiala, Nigeria. Trop Doctor. 1991;21:182–183. doi: 10.1177/004947559102100419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eze CB. Limb gangrene in traditional Orthopaedic (Bone Setters) practice and amputation at the NOHE - facts and fallacies. Nig Med J. 1991;21:125. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green SA. Orthopaedic Surgeons, Inheritors of tradition. Clin Orthopaedic Relat Res. 1999 Jun;(363):258–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adebule GT. The Bone Setters Elbow the Question of a justifiable But Difficult Moral Dilemma for the Orthopaedic surgeon. Nig Med J. 1991;21:126. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solagberu BA. The complications seen from the treatment by TBS. WAJM. 2003;22(4):343–345. letter. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonge TO, Dongo AE, Nottidge TE, Omololu AB, Ogunlade SO. Traditional bone setters in South Western Nigeria - Friends or Foes? WAJM. 2004;23(1):81–84. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v23i1.28091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solagberu BA. Long bone fractures treated by TBS; A study of patients' behaviour. Tropical doctor. 2005;35:106–107. doi: 10.1258/0049475054036797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oyebola DD. Yoruba traditional bonesetters: the practice of orthopaedics in a primitive setting in Nigeria. J trauma. 1980 Apr;20(4):312–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onuminya JE. Misadventure in traditional Medicine Practice: an unusual indication for limb amputation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Jun;97(6):824–825. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nwankwo OE, Katchy AU. Limb gangrene following treatment of limb injury by traditional bone setter (Tbs): a report of 15 consecutive cases. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2005 Mar;12(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onuminya JE, Obekpa PO, Ihezue HC, et al. Major amputations in Nigeria: a plea to educate traditional bone setters. Trop Doct. 2000 Jul;30(3):133–135. doi: 10.1177/004947550003000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekere AU. The scope of extremity amputations in a private hospital in South-South region of Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2003 Oct-Dec;12(4):2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.OlaOlorun DA, Oladiran IO, Adeniran A. complications of fracture treatment by traditional bone setters in Southwest Nigeria. Fam Pract. 2001 Dec;18(6):635–637. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garba ES, Deshi PJ. Traditional bone setting: a risk factor in limb amputation. East Afr Med J. 1988 Sep;75(9):553–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yakubu A, Mohammad I, Mabogunye O. Limb amputation in children in Zaria, Nigeria. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1995 Jun;15(2):163–165. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1995.11747766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eshete M. The prevention of traditional bone setter's gangrene. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005 Jan;87(1):102–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garba ES, Deshi PJ, Iheirka KE. The role of traditional bone setters in limb amputation in Zaria. Nig J Surg Res. 1999;1:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oguachuba HN. Mismanagement of elbow joint fractures and dislocations by traditional bone setters in Plateau State, Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1986;38(2):167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oguachuba HN. Dislocation and fracture dislocation of hip joints treatment by traditional bone setters in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1986;38(2):172–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatipoglu S, Tatar K. The strength and weaknesses of Turkish bone setters. World Health forum. 1995;16(2):203–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omololu AB, Ogunlade SO, Gopaldsani VR. The practice of Traditional Bonesetting: Training algorithin. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2392–2398. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dada A, Giwa SO, Yinusa W, Ugbeye M, Gbadegesin S. Complications of Treatment of Musculoskeletal Injuries by Bone Setters. WAJM. 2009;28(i):43–47. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v28i1.48426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikpeme IA, Udosen AM, Okereke-Okpa I. Patients Perception of traditional Bones Setting in Calabar. Port Harcourt Med J. 2007;1:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onuminya JE. performance of a trained traditional bonesetter in primary fracture care. S Afr Med J. 2006 Apr;96(4):320–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eshete E. The Prevention of traditional bonesetters gangrene. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87-B:102–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]