Abstract

The typical mammalian visual system is based upon three photoreceptor types: rods for dim light vision and two types of cones (M and S) for color vision in daylight. However, the process that generates photoreceptor diversity and the cell type in which diversity arises remain unclear. Mice deleted for thyroid hormone receptor β2 (TRβ2) and neural retina leucine zipper factor (NRL) lack M cones and rods, respectively, but gain S cones. We therefore tested the hypothesis that NRL and TRβ2 direct a common precursor to a rod, M cone, or S cone outcome using Nrlb2/b2 “knock-in” mice that express TRβ2 instead of NRL from the endogenous Nrl gene. Nrlb2/b2 mice lacked rods and produced excess M cones in contrast to the excess S cones in Nrl−/− mice. Notably, the presence of both factors yielded rods in Nrl+/b2 mice. The results demonstrate innate plasticity in postmitotic rod precursors that allows these cells to form three functional photoreceptor types in response to NRL or TRβ2. We also detected precursor cells in normal embryonic retina that transiently coexpressed Nrl and TRβ2, suggesting that some precursors may originate in a plastic state. The plasticity of the precursors revealed in Nrlb2/b2 mice suggests that a two-step transcriptional switch can direct three photoreceptor fates: first, rod versus cone identity dictated by NRL, and second, if NRL fails to act, M versus S cone identity dictated by TRβ2.

Introduction

The visual capability of a species depends upon the generation of distinct photoreceptor types. Most mammals, including mice, possess three photoreceptor types: rods for dim light vision and two cone types for bright light vision. Cone types are defined by expression of medium-long (M) and short (S) wavelength-sensitive opsin photopigments, respectively, that allow color discrimination (Nathans, 1999). In the retina, multipotent, proliferative progenitor cells produce postmitotic progeny, or precursors, with diverse neuronal fates (Carter-Dawson and LaVail, 1979b; Cepko et al., 1996; Adler and Raymond, 2008). Progenitors are thought to change their properties as development progresses, thereby permitting the generation of the requisite variety of neuronal types, including rods, cones, horizontal, amacrine, bipolar, and ganglion cells that constitute the mature retina (Livesey and Cepko, 2001; Brzezinski and Reh, 2010). Classical cell birth-dating studies using 3H-thymidine pulses in early mouse development followed by morphological identification of cell types at adult ages indicated that cones are generated in the embryo, whereas rods are produced over a longer time extending into the postnatal period (Carter-Dawson and LaVail, 1979b; Young, 1985). However, rods and cones remain morphologically indistinct for much of their early life history, which has hindered direct studies of the events that generate photoreceptor diversity.

Transcription factors play critical roles throughout the course of photoreceptor differentiation from multipotent progenitor cell to postmitotic precursor to terminally differentiated neuron. Regarding the mechanisms by which photoreceptor diversity arises, we previously reported that neural retina leucine zipper factor (NRL, encoded by Nrl) and thyroid hormone receptor 2 (TRβ2, one of the receptor isoforms encoded by Thrb), profoundly influence photoreceptor fates. Nrl−/− mice lack rods but gain excess S cones (Mears et al., 2001), whereas Thrb2−/− mice lack M cones, and all cones instead express S opsin (Ng et al., 2001). Moreover, bromodeoxyuridine labeling indicates that NRL and TRβ2 are expressed in postmitotic precursors rather than dividing progenitors (Akimoto et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2007), leading us to hypothesize that in mice, photoreceptor diversity originates in a common, postmitotic photoreceptor precursor with default S cone properties.

To investigate the nature of the cell type in which photoreceptor diversity arises, we analyzed mice in which Nrl was replaced with a Thrb mini-gene that expresses TRβ2. The data demonstrate that postmitotic precursors that would normally form rods can alternatively produce M cones, S cones, or rods, depending upon the relative activities of NRL and TRβ2. We propose that the innate plasticity of this precursor allows a sequential, two-step transcriptional switch to direct three photoreceptor cell fates.

Materials and Methods

Mouse strains.

Nrl−/− mice were on a C57BL/6J background (Mears et al., 2001) and Tshr−/− mice on a 129/Sv × C57BL/6J background (Marians et al., 2002). Thrbtm2/tm2 (Thrb2−/−) mice (Ng et al., 2001) on a 129/Sv × C57BL/6J × DBA background carried a targeted replacement of lacZ in the TRβ2-specific exon of Thrb, resulting in expression of β-galactosidase from the endogenous TRβ2 promoter. The Nrlp-GFP transgene (Akimoto et al., 2006) was on a wild-type C57BL/6 background; these mice also carried a Thrb2p-lacZ transgene with the natural TRβ2 promoter and intron enhancer that direct expression in immature cones (Jones et al., 2007) to allow triple fluorescent analyses. Nrlb2/b2 mice on a C57BL/6 background were derived by targeted mutagenesis in C57BL/6 ES cells by Ozgene Pty Ltd. The targeting vector carried 5′ and 3′ homology arms of 4.7 and 4.3 kb, respectively, of Nrl genomic DNA flanking a mouse TRβ2 cDNA (gift from W. Wood and E. C. Ridgway, University of Colorado, Denver, Colorado) (Wood et al., 1991) with a 59 bp 5′ non-coding sequence before the TRβ2 ATG codon, a 126 bp 3′ untranslated sequence after the stop codon, an SV40 polyadenylation site, and a neomycin (Neo)-resistance gene flanked by loxP sites. Chimeric mice derived from a recombinant ES cell clone were crossed with Cre-transgenic mice to remove Neo; the Cre transgene was removed by out-crossing. Targeting was ascertained by Southern blot analysis. Nrl+/b2 mice were crossed to produce +/+, +/b2, and b2/b2 progeny for analyses. Genotypes were determined using a three-primer PCR with primers: Nrl-104F, 5′-GAACACCTCTCTCTGCTCAGTCCC; Thrb2-1522R, 5′-GGCTGAGGGCCATGTCCAAGTC; Nrl-512R, 5′CTGGACATGCTGGGCTCCTGTCTC, giving bands of 450 and 250 bp for wild-type and Nrl-b2 alleles, respectively. For developmental studies before adult ages, mice of either sex were analyzed. For histology and electroretinogram studies at adult ages, the sex of mice analyzed is given. Studies were performed according to approved protocols at NIDDK/NIH.

In situ hybridization and quantitative PCR analysis.

In situ hybridization was performed with riboprobes as described previously (Jia et al., 2009). For 8-week-old mice (see Fig. 4A), groups of 3 mice of either sex for each genotype were analyzed. The Thrb probe spanned the common C terminus of TRβ2 and TRβ1 (accession no. NM_001113417, coordinates 124–1701). For real-time quantitative PCR, retinal RNA was pooled from 3–5 mice. Gene expression levels were normalized to actin (Jia et al., 2009). Primers, accession numbers, and amplicon sizes are as follows: Opn1mw NM_008106, 162 bp, forward (F), 5′TCGAAACTGCATCTTACATCTC, reverse (R), 5′GGAGGTAAAACATGGCCAAA; Opn1sw AF190670, 176 bp, F, 5′TGCTGGGGATCTGAGATGAT, R, 5′AATGAGGTGAGGCCATTCTG, Thrb2 NM_009380.3, 208 bp, F, 5′CCTGTAGTTACCCTGGAAACCTG, R, 5′TACCCTGTGGCTTTGTCCC; Actb NM_007393.3, 222 bp, F, 5′TGCTGTCCCTGTATGCCTCTG, R, 5′TTGATGTCACGCACGATTTCC. Most primers were designed using PrimerBank guidelines (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank).

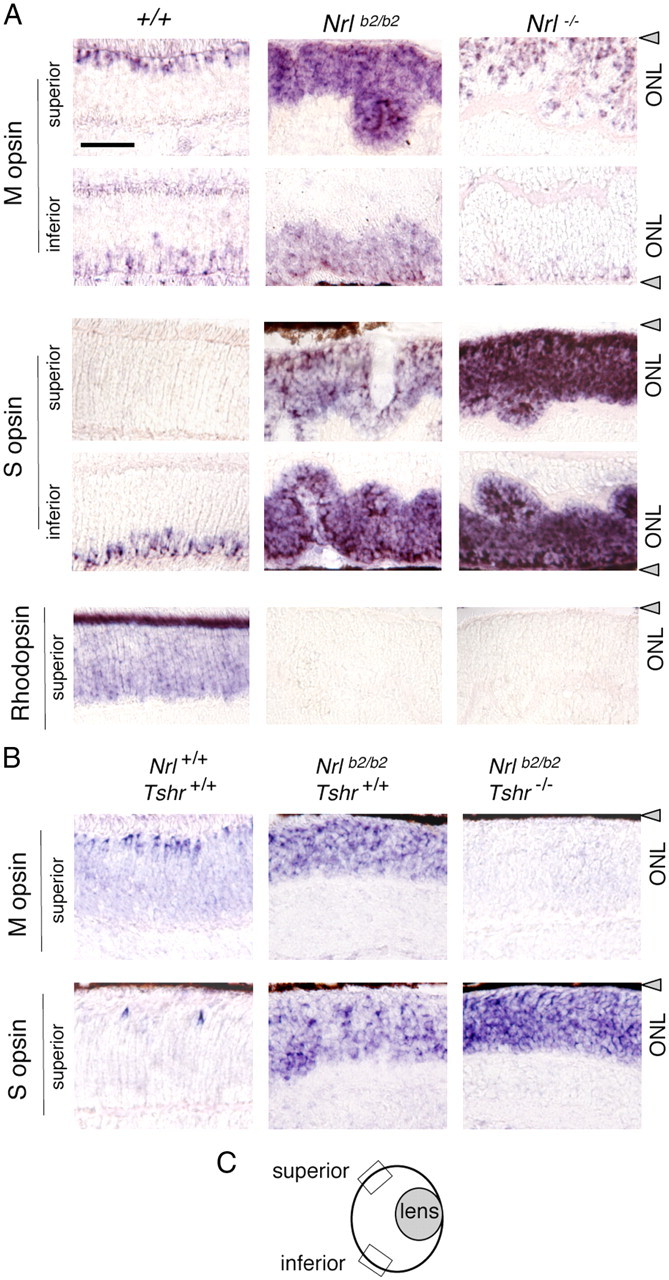

Figure 4.

Differential distribution of M and S opsins in Nrlb2/b2 and Nrl−/− mice. A, In situ hybridization analysis of cone opsin and rhodopsin mRNA in superior and inferior retinal regions in 8-week-old mice. Nrlb2/b2 mice overexpressed M and S opsins with a normal distribution trend, whereas in Nrl−/− mice, S opsin was strongly overexpressed in all retinal regions. Nrl−/− mice showed a small increase in the density of M opsin-positive cells in superior regions compared with +/+ mice, partly due to ONL folding in Nrl−/− mice. B, In situ hybridization analysis of opsin mRNA in hypothyroid Nrlb2/b2 mice at P17. On a hypothyroid Tshr−/− background, M opsin expression was retarded and S opsin overexpression exacerbated in Nrlb2/b2 mice. Scale bar: A (for A, B), 50 μm. C, Diagram of mouse eye section indicating location of superior and inferior retinal fields examined (boxes). Gray triangles, Retinal pigmented epithelium.

Western blot analysis.

Retinas from 2–4 embryos or mice were pooled to prepare whole-cell protein extracts as described previously (Lu et al., 2009). For adults, 15 μg samples and for embryos or neonates, 25 μg samples (unboiled) were analyzed by PAGE; rhodopsin was analyzed in 3 μg samples. Antibodies, dilutions, and sources are as follows: Nrl, rabbit polyclonal, 1:10,000 (Swain et al., 2001); TRβ2, rabbit polyclonal, 1:2500 (Ng et al., 2009); M opsin, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000 (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents Ab5405); S opsin, goat polyclonal, 1:250 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc14363); rhodopsin, mouse monoclonal, 1:2000 (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents MAb5316); actin, mouse monoclonal, 1:5000 (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents MAb1501).

Immunohistochemistry.

Ten-micrometer cryosections were incubated with antibodies and analyzed using a Leica SPE or Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope and a 63× oil-immersion lens (NA 1.4). Counts of TRβ2+ and GFP+ cells were determined in a single, 1 μm z-plane in mid-retinal sections. Counts were determined in 3 fields in the outer neuroblastic layer in the superior, middle, and inferior regions each of retina for groups of 3–5 mice. Antibody types, dilutions for use, and sources are as follows: S opsin, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000 (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents AB5407); β-galactosidase (E. coli), mouse monoclonal, 1:200 (Promega Z378A); TRβ2, rabbit polyclonal, 1: 2500 (Ng et al., 2009). The polyclonal antiserum raised in rabbit against full-length mouse NRL, described previously (Swain et al., 2001), was purified to select for the IgG fraction using protein A-Sepharose beads. This IgG fraction was used at 1:1000 dilution for immunohistochemistry.

Histology.

Three-micrometer glycol methacrylate sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Jia et al., 2009). Cone and rod nuclei were counted in 165-μm-long fields of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) in 2 representative fields per section on 3 mid-retinal, vertical sections in groups of 3 mice (all males). Statistical tests used Student's t test.

Electroretinogram analysis.

The electroretinogram (ERG) was recorded using an Espion Electrophysiology System (Diagnosys LLC) on 8- to 10-week-old mice anesthetized with (in milligrams per gram body weight) 25 ketamine, 10 xylazine, and 1000 urethane, as described previously (Lyubarsky et al., 1999; Ng et al., 2010). Briefly, photopic cone b-wave responses were measured with rod responses suppressed by constant green light (λ 520 nm) at 10 cd/m2. S opsin responses were evoked with a UV light-emitting diode (LED) with a peak at 367 nm and intensities of 0.0001, 0.0002, 0.00032, 0.00056, 0.001, 0.0018, 0.0032, 0.0056, 0.01, 0.0178, 0.0316, and 0.056 cd/m2. M opsin responses were evoked using an LED with a peak at 520 nm and intensities of 0.5, 1, 1.26, 1.58, 2, 2.51, 3.16, 3.98, 5.01, 6.31, 7.94, 10, 12.59, 15.84, 19.95, 25.12, 32, and 38 cd/m2. Scotopic rod responses were evoked after overnight dark adaptation using an LED with a peak at 520 nm at intensities of 1 × 10−6, × 10−5, × 10−4, × 10−3, and × 10−2 cd/m2. The ERG was recorded twice on separate groups of 4–6 mice (7–8 weeks old) of either sex, with males and females in approximately equal proportions for each of the six genotypes analyzed.

Results

Ectopic expression of TRβ2 from the Nrl gene

Our hypothesis that three photoreceptor types originate from a common, postmitotic precursor with default S cone properties was suggested by the profound shifts in photoreceptor fates observed in Nrl−/− and Thrb2−/− mice, both of which gain S cones at the expense of rods and M cones, respectively (Swaroop et al., 2010). To define the roles of NRL and TRβ2 in a common precursor, we investigated photoreceptor fates and function in mice in which the Nrl gene was replaced with a TRβ2-expressing cassette (Thrb2) by homologous recombination (Fig. 1A). This model would allow us to determine: (1) in heterozygotes, the consequence of coexpression of NRL and TRβ2 in a defined precursor population that normally forms rods; and (2) in homozygotes, the role of TRβ2 in the absence of NRL in this same precursor population.

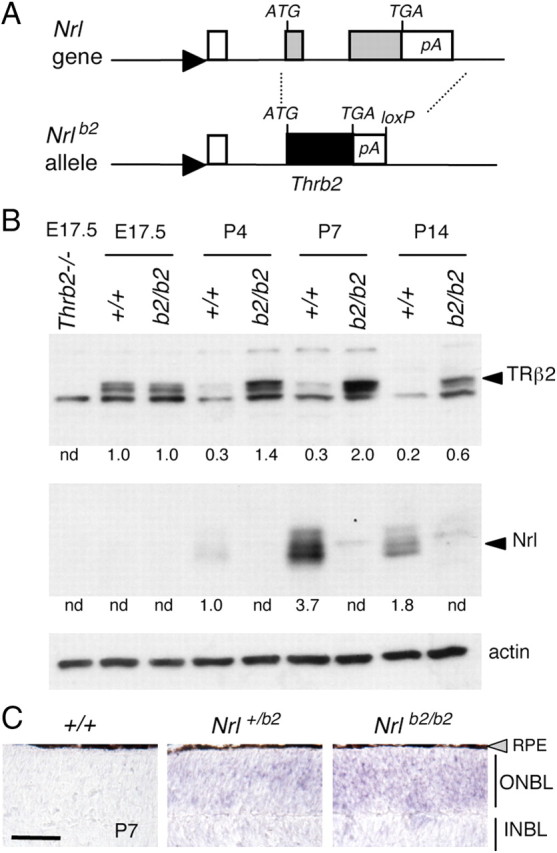

Figure 1.

Targeted replacement of Nrl gene with a Thrb2 gene. A, A Thrb2 cDNA, inserted at the start codon of Nrl, replaced both Nrl coding exons (gray boxes), creating the Nrlb2 allele. Filled triangle, Nrl gene promoter, open box, 5′-non-coding exon; TGA, stop codon; pA, polyadenylation site; loxP, residual loxP site after deletion of Neo selection gene. B, Western blot analysis showing expression of TRβ2 in Nrlb2/b2 mice. Arrowheads, specific bands for TRβ2 (∼58 kDa) and NRL (29–35 kDa). Thrb2−/− lane, TRβ2-deficient control at embryonic day 17.5 (E17.5). Numbers below lanes are signals quantified by densitometry relative to an arbitrary value of 1.0 in +/+ mice at the earliest age of detection; nd, not detectable. C, In situ hybridization showing ectopic expression of TRβ mRNA over the outer neuroblastic layer (ONBL) in Nrl+/b2 and Nrlb2/b2 mice at P7. Endogenous TRβ2 mRNA drops to low levels in the small cone population in +/+ neonates. Scale bar, 50 μm. INBL, Inner neuroblastic layer. RPE, Retinal pigmented epithelium (gray triangle).

Western blot analysis revealed the predicted loss of NRL and ectopic expression of TRβ2 in the retina of mice homozygous for this Nrlb2 allele (Fig. 1B). Normally, Nrl expression peaks during the first postnatal week, whereas TRβ2 peaks in utero (Akimoto et al., 2006; Ng et al., 2009), correlating with the peaks of birth of immature rods and cones, respectively (Carter-Dawson and LaVail, 1979b). In Nrlb2/b2 mice, TRβ2 showed protracted postnatal expression with a peak at postnatal day 7 (P7), as expected when expressed from the endogenous Nrl promoter. In situ hybridization analysis revealed ectopic expression of TRβ2 mRNA over the entire outer neuroblastic layer (ONBL) of the retina in Nrlb2/b2 and Nrl+/b2 mice at P7, consistent with expression in the large precursor population that normally forms rods (Fig. 1C). In contrast, TRβ2 mRNA expression in the small cone population in wild-type (+/+) mice had declined to nearly undetectable levels at P7.

Histology of the photoreceptor layer in Nrl+/b2 and Nrlb2/b2 mice

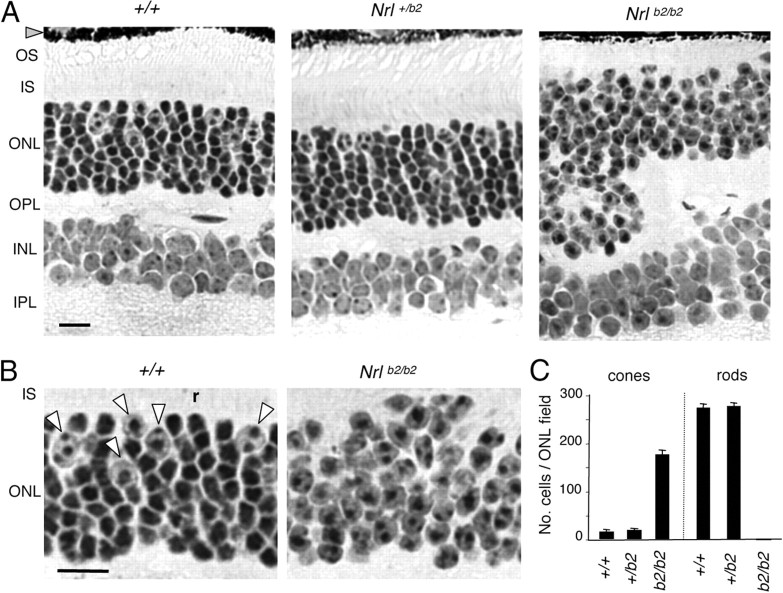

The retina of adult Nrlb2/b2 mice was morphologically indistinguishable from that of Nrl−/− mice in displaying excess cones and a complete absence of rods, as expected following loss of Nrl (Fig. 2A,B). Nrlb2/b2 mice, like Nrl−/− mice (Daniele et al., 2005), also displayed shortened outer segments and “rosette” distortions of the ONL, possibly due to aberrant packing and displacement of cone cell bodies, which are larger than rod cell bodies. In contrast, in heterozygous Nrl+/b2 mice, normal numbers of cones and rods were present (Fig. 2A,C). Cones were identified by their large nuclei with dispersed chromatin and their location near the outer edge of the ONL, whereas rods were distinguished by their small, densely stained nuclei and their large numbers distributed throughout the ONL (Carter-Dawson and LaVail, 1979a). Thus, ectopic expression of TRβ2 in heterozygous Nrl+/b2 mice did not alter retinal morphology or the numbers of rods and cones compared with +/+ mice, indicating that coexpression of TRβ2 with NRL in rod precursors did not divert differentiation from a rod outcome.

Figure 2.

Retinal histology in Nrl+/b2 and Nrlb2/b2 mice. A, Retinal histology in 3-month-old mice. The ONL in Nrl+/b2 mice contains cones (large nuclei with dispersed chromatin) and rods (smaller, denser nuclei) in the same proportions as +/+ mice. Nrlb2/b2 mice, like Nrl−/− mice, lack rods, have excess cones, and also display ONL folding and shortened outer segments (OS). INL, Inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; IS, inner segments; OPL, outer plexiform layer. B, Higher magnification from images in A indicating cone nuclei (arrowheads) and a representative rod nucleus (r) in a +/+ mouse. Nrlb2/b2 mice possess only cone-like nuclei. Scale bars: A, B, 20 μm. C, Counts (mean ± SD) of cone and rod nuclei in ONL fields, determined on 3-μm-thick plastic sections like those in A. Fields avoided grossly folded areas in Nrlb2/b2 mice. Gray triangle, Retinal pigmented epithelium.

Distinct photoreceptor outcomes in Nrl+/b2, Nrl b2/b2 and Nrl−/− mice

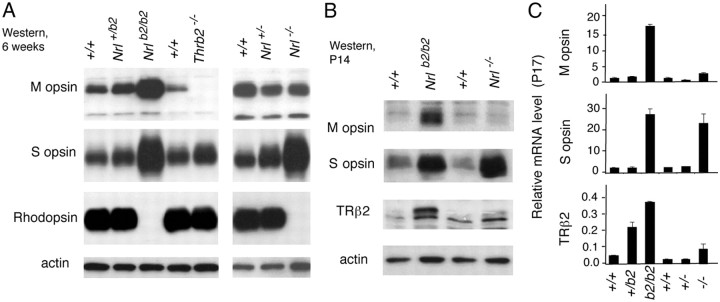

The photoreceptor outcomes of the different mouse strains were further determined by analysis of expression of cone and rod photopigments (Fig. 3), by analysis of the spatial distribution of cone photopigments over the retina (Fig. 4A), and by testing the dependence of photopigment expression upon thyroid hormone (Fig. 4B). First, Western blot and mRNA analyses demonstrated that in Nrlb2/b2 mice, like Nrl−/− mice, the retina overexpressed S opsin and lacked the rod photopigment rhodopsin (Fig. 3A,C). However, Nrlb2/b2 mice differed from Nrl−/− mice in the key property of overexpression of M opsin. Heterozygous Nrl+/b2 mice showed little or no abnormality in cone opsin or rhodopsin expression, indicating that TRβ2 is largely constrained from regulating cone opsins in a rod cellular context. The overexpression of M opsin in Nrlb2/b2 mice displayed an early onset and was already pronounced at P14 (Fig. 3B). Similar findings were made at the mRNA level using quantitative PCR analysis (Fig. 3C), indicating that the phenotypic difference between Nrlb2/b2 and Nrl−/− mice reflected changes in the transcriptional program.

Figure 3.

Distinct photoreceptor outcomes in Nrlb2/b2 and Nrl−/− mice. A, Western blot analysis of cone opsins and rhodopsin in retina from 6-week-old mice of the indicated Nrl genotypes. Thrb2−/− lane, Sample from TRβ2-deficient mice as a negative control for M opsin. B, Western blot analysis of cone opsins and TRβ2 in retina from P14 mice of the indicated Nrl genotypes. The initial induction of M opsin is pronounced in Nrlb2/b2 mice at this juvenile age. C, Quantitative PCR analysis of M opsin, S opsin, and TRβ2 mRNA levels in retina of mice of the indicated Nrl genotypes at P17.

Normally, M and S opsins are differentially distributed across the mouse retina, with M opsin predominating in superior and S opsin in inferior retinal regions, while cones in middle regions express varying proportions of both M and S opsins (Lyubarsky et al., 1999; Applebury et al., 2000; Szél et al., 2000). In the excess S cones in Nrl−/− mice, this pattern is lost, with S opsin being strongly overexpressed regardless of regional location in the retina, as shown by in situ hybridization analysis (Fig. 4A). However, ectopic TRβ2 expression imposed a normal distribution trend on M and S opsins in the excess cones in Nrlb2/b2 mice such that M opsin was predominantly expressed in superior and S opsin in inferior retinal regions.

Further experiments demonstrated that the excess cones in Nrlb2/b2 mice, like normal cones, were dependent on provision of thyroid hormone for M and S opsin patterning. Nrlb2/b2 mice were made congenitally hypothyroid by crossing with Tshr−/− mice (Marians et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2009). Tshr−/− mice have very low serum levels of thyroid hormones from birth because of an underdeveloped thyroid gland resulting from loss of the thyrotropin receptor. In Nrlb2/b2 mice on a Tshr−/− background, M opsin expression was retarded and S opsin overexpression was exacerbated in both superior and inferior retinal regions (Fig. 4B). Rhodopsin remained undetectable in Nrlb2/b2 mice regardless of Tshr genotype.

Distinct photoreceptor functions in Nrl+/b2, Nrlb2/b2, and Nrl−/− mice

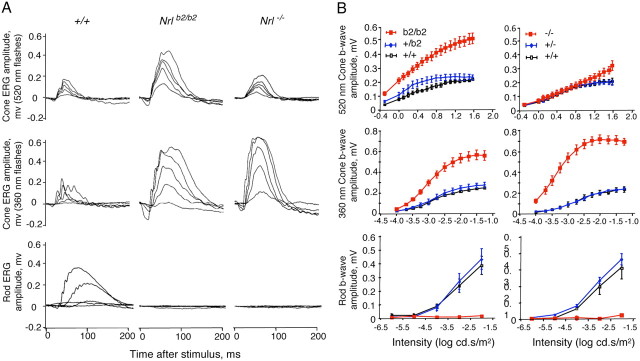

Analysis of the photopic ERG revealed a striking enhancement of M cone function in Nrlb2/b2 mice, consistent with the presence of M opsin in the excess cone photoreceptors in this mouse strain. Cone b-wave magnitudes were substantially elevated in response to a monochromatic light stimulus with a wavelength of 520 nm that optimally activates mouse M opsin (Lyubarsky et al., 1999; Ng et al., 2010) (Fig. 5A, top row). In contrast, Nrl−/− mice displayed M cone responses in the normal range. Both Nrlb2/b2 and Nrl−/− mice displayed markedly enhanced S cone responses to a stimulus at 360 nm, a wavelength that optimally activates mouse S opsin (Fig. 5A, middle row). However, the magnitude of the enhanced S cone response was somewhat lower in Nrlb2/b2 mice than in Nrl−/− mice, as shown in the stimulus intensity–response plots (Fig. 5B). The smaller enhancement of the S cone response in Nrlb2/b2 mice is consistent with the more restricted distribution of S opsin in the retina in Nrlb2/b2 mice than Nrl−/− mice. Both Nrlb2/b2 and Nrl−/− mice lacked scotopic ERG responses as expected in the absence of rods (Fig. 5A, bottom row). In conclusion, these results indicate that in the absence of NRL, both Nrlb2/b2 and Nrl−/− mice produce excess, functional cones instead of rods. However, the results in Nrlb2/b2 mice indicate that precursors that would normally become rods are capable of forming functional M cones, as an alternative to the S cones found in Nrl−/− mice. Finally, heterozygous Nrl+/b2 mice displayed rod responses in the normal range, indicating that in mice with this genotype, the rod population (Fig. 2) was functionally intact.

Figure 5.

Distinct cone and rod functional responses in Nrl+/b2, Nrlb2/b2, and Nrl−/− mice. A, Representative electroretinogram traces for Nrlb2/b2 and Nrl−/− mice at ∼8 weeks of age. Top and middle rows, Photopic cone responses to stimuli with wavelengths of 520 and 360 nm that optimally activate mouse M and S opsins, respectively. Bottom row, Scotopic rod responses. Enhanced M and S cone responses were detected in Nrlb2/b2 mice, but only enhanced S cone responses in Nrl−/− mice. Families of traces are shown for light intensities of 0.5, 1.26, 2, 3.16, and 7.94 cd · s/m2 at 520 nm and 0.0001, 0.00032, 0.001, 0.0032 and 0.0316 cd · s/m2 at 360 nm for cones and 1 × 10−6, × 10−5, × 10−4, × 10−3, and × 10−2 cd · s/m2 for rods. B, Intensity–response curves of average ERG responses for groups of 4–6 mice (means ± SEM). Cone (top and middle rows) and rod (bottom row) ERG responses to varying stimulus intensities were determined for +/+, Nrl+/b2, and Nrlb2/b2 mice and, separately, for +/+, Nrl+/−, and Nrl−/− mice. Nrlb2/b2 and Nrl−/− mice were each compared with their own +/+ and heterozygous groups on comparable genetic backgrounds.

Transient coexpression of Nrl and TRβ2 in retinal development

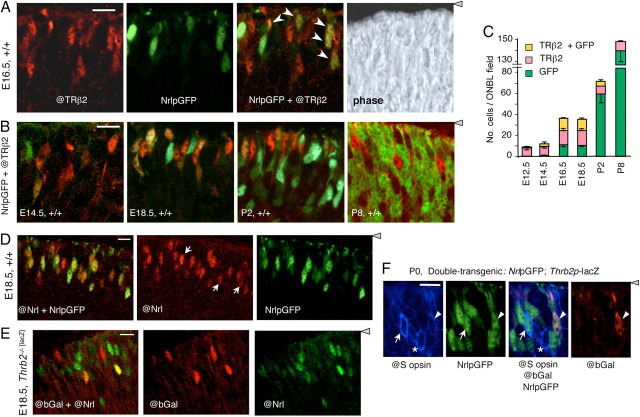

The above evidence from mouse strains carrying genetic alterations demonstrated that precursors that normally form rods are capable of forming M cones, S cones, or rods, depending upon the relative expression levels of NRL and TRβ2. We therefore tested whether common photoreceptor precursors in the normal retina may coexpress the early rod (NRL) and cone (TRβ2) markers at immature stages. TRβ2 was detected by immunofluorescence using antiserum against TRβ2 (@TRβ2), and Nrl expression was monitored by direct detection of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expressed from an Nrl promoter-GFP transgene (NrlpGFP) on a wild-type mouse background. This direct identification of immature cones and rods based on early markers revealed that the appearance of TRβ2-positive (TRβ2+) and NrlpGFP-positive (GFP+) cells followed the profiles of cone and rod genesis, respectively, determined indirectly in previous studies using 3H-thymidine labeling in mice (Carter-Dawson and LaVail, 1979b) (Fig. 6A,B). Thus, the cone peak preceded that of rods. However, up to 50% of TRβ2+ cells at later embryonic stages were also GFP+ (Fig. 6C). Postnatally, GFP+ cell numbers rose sharply, correlating with the peak of rod generation. By P8, no doubly positive cells were detected. The results revealed a transient population of cells that coexpressed TRβ2 and GFP, raising the possibility that some photoreceptor precursors originate in an indeterminate rather than fixed rod or cone state.

Figure 6.

Transient coexpression of TRβ2 and Nrl in photoreceptor precursors. A, Double fluorescence analysis of cells positive for TRβ2 (@TRβ2 antibody, red), NrlpGFP (transgene, green), or both @TRβ2 and NrlpGFP (yellow or orange, arrows in merged image) in the outer neuroblastic layer of +/+ mouse retina at E16.5. Right, Phase contrast image of the same field. Confocal microscope images represent a single 1–1.5 μm z-plane obtained from 10-μm-thick mid-retinal cryosections (same in B–E). For orientation, the gray arrowhead indicates location of retinal pigmented epithelium. B, Double fluorescence analysis of cells positive for TRβ2 and NrlpGFP in +/+ mouse retina during development at E14.5, E18.5, P2, and P8. Doubly positive cells (yellow or orange) were most evident at E16.5–E18.5. Scale bars: A, B, 14 μm. C, Counts of cells positive for TRβ2, GFP, or both TRβ2 and GFP, determined on single z-plane confocal images from experiments shown in A and B. Counts shown were determined in mid-retinal fields. Counts in superior and inferior fields gave similar results. D, Verification of NrlpGFP transgene as a marker for cells expressing endogenous Nrl using an antibody against NRL protein (@Nrl) and direct fluorescence for NrlpGFP in +/+ embryos at E18.5. The @Nrl+ population included almost all GFP+ cells (yellowish and orange cells, merged image on the left) and a few @Nrl+ cells that were negative for GFP (white arrows, middle). E, Independent identification of cells that coexpress TRβ2 (@bGal) and endogenous NRL protein (@Nrl) (yellow or orange cells in merged image, left). Analysis was performed on E18.5 embryos homozygous for a targeted insertion of lacZ in the TRβ2-specific exon of the Thrb gene. Scale bars: D, E, 10 μm F, Immunofluorescence analysis for coexpression of S opsin (@S opsin antibody, blue), NrlpGFP (direct fluorescence, green) and Thrb2p-lacZ transgenes (@bGal antibody, red, indicator for TRβ2) in +/+ mice at P0. Arrows, S opsin/GFP doubly positive cell; arrowheads, S opsin/GFP/bGal triply positive cell; asterisks, S opsin-positive cell with no detectable GFP or bGal. Gray triangle, Retinal pigmented epithelium.

The validity of the NrlpGFP transgene as a marker for cells expressing endogenous Nrl was verified by analysis with an antibody against NRL protein (@Nrl) (Fig. 6D). Both the antibody and NrlpGFP transgene detected cells with a range of signal strengths in the late embryonic retina. Almost all GFP+ cells were also positive for @Nrl. However, the @Nrl antibody detected some additional cells that were not GFP+ (Fig. 6D, white arrows, middle panel), suggesting that NrlpGFP had a slightly lower detection sensitivity than @Nrl antiserum. The presence of cells that were positive for both Nrl and TRβ2 was independently demonstrated in a reciprocal analysis using @Nrl to detect endogenous NRL protein and an antibody against β-galactosidase (@bGal) to detect expression of a targeted lacZ insertion in the TRβ2-specific exon of the endogenous Thrb gene (Ng et al., 2001). Cells positive for both @bGal and @Nrl were detected in these mice (Fig. 6E).

Using mice carrying NrlpGFP, we investigated whether any GFP+ precursors coexpressed S opsin, an indicator of the putative default S cone state of a precursor before acquisition of a fixed fate. These mice also carried a Thrb2p-lacZ transgene, a reporter of TRβ2 expression, thus allowing triple analysis of cells expressing Nrl, TRβ2, and S opsin. At late embryonic and neonatal stages, occasional doubly positive GFP+/S opsin+ cells were detected (Fig. 6F). Rare triply positive GFP+/TRβ2+/S opsin+ cells were also detected in neonates, suggesting that some precursors may originate in an indeterminate state.

Discussion

This study of Nrlb2/b2 mice demonstrates that postmitotic precursors that normally form rods possess an innate plasticity and can be directed to three functionally distinct photoreceptor outcomes by NRL and TRβ2 in vivo. This evidence, based upon manipulation of rod precursors, supports a hypothesis whereby photoreceptor diversity originates in a malleable precursor in response to two, stepwise decisions (Swaroop et al., 2010), as follows. (1) If NRL attains a critical threshold of expression, it suppresses a default S cone outcome and directs a rod fate. The retention of rods in Nrl+/b2 mice suggests that TRβ2 has little ability to deflect such a cell away from a rod outcome, consistent with NRL exerting transcriptional dominance (Oh et al., 2007). (2) If NRL expression fails to reach a threshold, differentiation proceeds by default as an S cone. In a subpopulation of these cells, TRβ2 determines an M opsin identity depending upon the spatial location of the cone in the retina and the developmental rise in thyroid hormone levels in the circulation (Roberts et al., 2006; Pessôa et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2009; Glaschke et al., 2010). Consequently, the plastic precursor acquires a fixed commitment to a particular photoreceptor fate. A distinctive feature of the hypothesis is the sequential, two-step control, with each step yielding a new outcome (rod or M cone) relative to a common default outcome (S cone). This contrasts with other models of cell fate determination in which two transcription factors exert mutual antagonism, as has been proposed, for example, for GATA1 and PU.1 in directing erythroid versus myeloid fates in blood cell differentiation (Graf and Enver, 2009).

Other evidence suggests that precursors of all cone and rod types, not only the rod type, possess innate plasticity. Thus, both TRβ2-deficient and NRL-deficient mice gain S cones at the expense of M cones and rods, respectively (Mears et al., 2001; Ng et al., 2001). Moreover, ectopic expression of NRL in all types of photoreceptor precursors using a Crx promoter suppresses cone development and gives a rod-only retina (Oh et al., 2007), indicating that cone precursors are susceptible to the dominant activity of NRL. Based on this evidence and the results from Nrlb2/b2 mice, we may speculate that photoreceptor precursors possess equivalent plasticity when first generated from dividing progenitors. If so, the first distinction between rod and cone precursors may be set by the presently undefined signals that induce a threshold level of NRL expression in the population that will become rods.

We also detected precursors in normal retina that coexpressed TRβ2 and Nrl using two immunofluorescent approaches. This transient population of doubly positive cells was most evident at late embryonic stages and may reflect the presence of some normal precursors that exist in an indeterminate state before final commitment to a given photoreceptor fate. However, the developmental significance of these doubly positive precursors awaits future investigation, for example by cell lineage-tracing experiments. We note that a technical limitation in monitoring early differentiation stages concerns the changing and, at times very low, expression levels of cone and rod markers in development. For example, TRβ2 peaks in utero and declines postnatally, whereas Nrl expression is relatively weak in utero but increases postnatally. Such low and dynamically varying expression levels may lead to an underestimation of the number of doubly positive cells at some stages but would not change the major finding of this analysis.

Much interest has focused on multipotent progenitor cells as a source of neuronal diversity, with differentiation fates being programmed in the progenitor before or during exit from the cell cycle (Jacob et al., 2008; Agathocleous and Harris, 2009; Jukam and Desplan, 2010). Indeed, as development progresses, retinal progenitors are thought to change their differentiation properties, or competence, thereby allowing the generation of appropriate populations of photoreceptors, interneurons, ganglion cells, and glia (Livesey and Cepko, 2001). Nonetheless, concerning the cell type in which photoreceptor diversity arises, our study points to a postmitotic precursor rather than a progenitor as the source of diversity. The process that produces such a generic, plastic photoreceptor precursor from a progenitor is probably complex, involving, for example, Otx2 (Nishida et al., 2003), Blimp1 (Brzezinski et al., 2010; Katoh et al., 2010), and Notch signaling genes (Jadhav et al., 2006; Yaron et al., 2006; Riesenberg et al., 2009). However, NRL and TRβ2 are not required at this step. Rather, the requirement for NRL and TRβ2 is postponed until a malleable precursor is made that can be directed to a rod, M cone, or S cone fate by a limited combination of transcriptional switches.

Genes such as Nr2e3 (Haider et al., 2000), Crx (Chen et al., 1997; Furukawa et al., 1999), and Pias3 (Onishi et al., 2009, 2010) are also critical at various stages of photoreceptor differentiation and encode accessory factors or downstream effectors that participate closely with NRL or TRβ2. For example, NRL initially induces expression of orphan receptor NR2E3, and these two factors together activate rod genes and suppress cone genes (Oh et al., 2007). Coup-TF, retinoid-related orphan nuclear receptors, and retinoid receptors cooperate with TRβ2 in setting cone opsin distribution patterns (Roberts et al., 2005; Srinivas et al., 2006; Fujieda et al., 2009; Satoh et al., 2009; Alfano et al., 2011). Although the mechanisms of these interactions remain to be elucidated, current evidence does not indicate that other factors substitute for NRL and TRβ2 in the central decisions that initiate the generation of photoreceptor diversity.

It is of interest that analogous controls may direct photoreceptor diversity in non-mammalian species. The Drosophila compound eye consists of ommatidial units but nonetheless resembles the mammalian eye in containing both color-sensing and dim light-sensing photoreceptors. In the Drosophila eye, a mosaic of color-sensing photoreceptors is generated by stochastic expression of spineless factor in precursor cells. Spineless dictates which particular opsin is expressed, thereby generating “yellow” or “pale” ommatidial fates (Wernet et al., 2006). Although the factors differ, similarities in the transcriptional switches used in mice and insects may point to common themes underlying the generation of photoreceptor diversity.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the NIH intramural research program at NIDDK and NEI. We thank M. Ma and J. Nellissery for assistance, W. Wood and E. C. Ridgway for plasmids, T. F. Davies for Tshr−/− mice, and E. N. Pugh Jr and R. Bush for advice on ERG analyses.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Adler R, Raymond PA. Have we achieved a unified model of photoreceptor cell fate specification in vertebrates? Brain Res. 2008;1192:134–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agathocleous M, Harris WA. From progenitors to differentiated cells in the vertebrate retina. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:45–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto M, Cheng H, Zhu D, Brzezinski JA, Khanna R, Filippova E, Oh EC, Jing Y, Linares JL, Brooks M, Zareparsi S, Mears AJ, Hero A, Glaser T, Swaroop A. Targeting of GFP to newborn rods by Nrl promoter and temporal expression profiling of flow-sorted photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3890–3895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508214103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano G, Conte I, Caramico T, Avellino R, Arnò B, Pizzo MT, Tanimoto N, Beck SC, Huber G, Dollé P, Seeliger MW, Banfi S. Vax2 regulates retinoic acid distribution and cone opsin expression in the vertebrate eye. Development. 2011;138:261–271. doi: 10.1242/dev.051037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebury ML, Antoch MP, Baxter LC, Chun LL, Falk JD, Farhangfar F, Kage K, Krzystolik MG, Lyass LA, Robbins JT. The murine cone photoreceptor: a single cone type expresses both S and M opsins with retinal spatial patterning. Neuron. 2000;27:513–523. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski J, Reh T. Retinal histogenesis. In: Dartt D, Besharse J, Dada R, editors. Encyclopedia of the eye. Vol 4. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski JA, 4th, Lamba DA, Reh TA. Blimp1 controls photoreceptor versus bipolar cell fate choice during retinal development. Development. 2010;137:619–629. doi: 10.1242/dev.043968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Dawson LD, LaVail MM. Rods and cones in the mouse retina. I. Structural analysis using light and electron microscopy. J Comp Neurol. 1979a;188:245–262. doi: 10.1002/cne.901880204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Dawson LD, LaVail MM. Rods and cones in the mouse retina. II. Autoradiographic analysis of cell generation using tritiated thymidine. J Comp Neurol. 1979b;188:263–272. doi: 10.1002/cne.901880205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko CL, Austin CP, Yang X, Alexiades M, Ezzeddine D. Cell fate determination in the vertebrate retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:589–595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Wang QL, Nie Z, Sun H, Lennon G, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Zack DJ. Crx, a novel Otx-like paired-homeodomain protein, binds to and transactivates photoreceptor cell-specific genes. Neuron. 1997;19:1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele LL, Lillo C, Lyubarsky AL, Nikonov SS, Philp N, Mears AJ, Swaroop A, Williams DS, Pugh EN., Jr Cone-like morphological, molecular and physiological features of the photoreceptors of the Nrl knockout mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2156–2167. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujieda H, Bremner R, Mears AJ, Sasaki H. Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor α regulates a subset of cone genes during mouse retinal development. J Neurochem. 2009;108:91–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Morrow EM, Li T, Davis FC, Cepko CL. Retinopathy and attenuated circadian entrainment in Crx-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1999;23:466–470. doi: 10.1038/70591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaschke A, Glösmann M, Peichl L. Developmental changes of cone opsin expression but not retinal morphology in the hypothyroid Pax8 knockout mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1719–1727. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf T, Enver T. Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature. 2009;462:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nature08533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider NB, Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Swiderski R, Streb LM, Searby C, Beck G, Hockey R, Hanna DB, Gorman S, Duhl D, Carmi R, Bennett J, Weleber RG, Fishman GA, Wright AF, Stone EM, Sheffield VC. Mutation of a nuclear receptor gene, NR2E3, causes enhanced S cone syndrome, a disorder of retinal cell fate. Nat Genet. 2000;24:127–131. doi: 10.1038/72777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob J, Maurange C, Gould AP. Temporal control of neuronal diversity: common regulatory principles in insects and vertebrates? Development. 2008;135:3481–3489. doi: 10.1242/dev.016931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav AP, Mason HA, Cepko CL. Notch 1 inhibits photoreceptor production in the developing mammalian retina. Development. 2006;133:913–923. doi: 10.1242/dev.02245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Oh EC, Ng L, Srinivas M, Brooks M, Swaroop A, Forrest D. Retinoid-related orphan nuclear receptor RORβ is an early-acting factor in rod photoreceptor development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17534–17539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902425106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones I, Ng L, Liu H, Forrest D. An intron control region differentially regulates expression of thyroid hormone receptor β2 in the cochlea, pituitary, and cone photoreceptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1108–1119. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukam D, Desplan C. Binary fate decisions in differentiating neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Omori Y, Onishi A, Sato S, Kondo M, Furukawa T. Blimp1 suppresses Chx10 expression in differentiating retinal photoreceptor precursors to ensure proper photoreceptor development. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6515–6526. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0771-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey FJ, Cepko CL. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: lessons from the retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:109–118. doi: 10.1038/35053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu A, Ng L, Ma M, Kefas B, Davies TF, Hernandez A, Chan CC, Forrest D. Retarded developmental expression and patterning of retinal cone opsins in hypothyroid mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1536–1544. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubarsky AL, Falsini B, Pennesi ME, Valentini P, Pugh EN., Jr UV- and midwave-sensitive cone-driven retinal responses of the mouse: a possible phenotype for coexpression of cone photopigments. J Neurosci. 1999;19:442–455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00442.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marians RC, Ng L, Blair HC, Unger P, Graves PN, Davies TF. Defining thyrotropin-dependent and -independent steps of thyroid hormone synthesis by using thyrotropin receptor-null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15776–15781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242322099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears AJ, Kondo M, Swain PK, Takada Y, Bush RA, Saunders TL, Sieving PA, Swaroop A. Nrl is required for rod photoreceptor development. Nat Genet. 2001;29:447–452. doi: 10.1038/ng774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathans J. The evolution and physiology of human color vision: insights from molecular genetic studies of visual pigments. Neuron. 1999;24:299–312. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng L, Hurley JB, Dierks B, Srinivas M, Saltó C, Vennström B, Reh TA, Forrest D. A thyroid hormone receptor that is required for the development of green cone photoreceptors. Nat Genet. 2001;27:94–98. doi: 10.1038/83829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng L, Ma M, Curran T, Forrest D. Developmental expression of thyroid hormone receptor β2 protein in cone photoreceptors in the mouse. Neuroreport. 2009;20:627–631. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832a2c63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng L, Lyubarsky A, Nikonov SS, Ma M, Srinivas M, Kefas B, St Germain DL, Hernandez A, Pugh EN, Jr, Forrest D. Type 3 deiodinase, a thyroid-hormone-inactivating enzyme, controls survival and maturation of cone photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3347–3357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5267-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida A, Furukawa A, Koike C, Tano Y, Aizawa S, Matsuo I, Furukawa T. Otx2 homeobox gene controls retinal photoreceptor cell fate and pineal gland development. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1255–1263. doi: 10.1038/nn1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh EC, Khan N, Novelli E, Khanna H, Strettoi E, Swaroop A. Transformation of cone precursors to functional rod photoreceptors by bZIP transcription factor NRL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1679–1684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605934104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi A, Peng GH, Hsu C, Alexis U, Chen S, Blackshaw S. Pias3-Dependent SUMOylation Directs Rod Photoreceptor Development. Neuron. 2009;61:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi A, Peng GH, Chen S, Blackshaw S. Pias3-dependent SUMOylation controls mammalian cone photoreceptor differentiation. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1059–1065. doi: 10.1038/nn.2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessôa CN, Santiago LA, Santiago DA, Machado DS, Rocha FA, Ventura DF, Hokoç JN, Pazos-Moura CC, Wondisford FE, Gardino PF, Ortiga-Carvalho TM. Thyroid hormone action is required for normal cone opsin expression during mouse retinal development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2039–2045. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesenberg AN, Liu Z, Kopan R, Brown NL. Rbpj cell autonomous regulation of retinal ganglion cell and cone photoreceptor fates in the mouse retina. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12865–12877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3382-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MR, Hendrickson A, McGuire CR, Reh TA. Retinoid X receptor γ is necessary to establish the S-opsin gradient in cone photoreceptors of the developing mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2897–2904. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MR, Srinivas M, Forrest D, Morreale de Escobar G, Reh TA. Making the gradient: thyroid hormone regulates cone opsin expression in the developing mouse retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6218–6223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509981103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh S, Tang K, Iida A, Inoue M, Kodama T, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, Furuta Y, Watanabe S. The spatial patterning of mouse cone opsin expression is regulated by bone morphogenetic protein signaling through downstream effector COUP-TF nuclear receptors. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12401–12411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0951-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas M, Ng L, Liu H, Jia L, Forrest D. Activation of the blue opsin gene in cone photoreceptor development by retinoid-related orphan receptor β. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1728–1741. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain PK, Hicks D, Mears AJ, Apel IJ, Smith JE, John SK, Hendrickson A, Milam AH, Swaroop A. Multiple phosphorylated isoforms of NRL are expressed in rod photoreceptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36824–36830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaroop A, Kim D, Forrest D. Transcriptional regulation of photoreceptor development and homeostasis in the mammalian retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:563–576. doi: 10.1038/nrn2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szél A, Lukáts A, Fekete T, Szepessy Z, Röhlich P. Photoreceptor distribution in the retinas of subprimate mammals. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2000;17:568–579. doi: 10.1364/josaa.17.000568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernet MF, Mazzoni EO, Celik A, Duncan DM, Duncan I, Desplan C. Stochastic spineless expression creates the retinal mosaic for colour vision. Nature. 2006;440:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature04615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood WM, Ocran KW, Gordon DF, Ridgway EC. Isolation and characterization of mouse complementary DNAs encoding α and β thyroid hormone receptors from thyrotrope cells: the mouse pituitary-specific β2 isoform differs at the amino terminus from the corresponding species from rat pituitary tumor cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1049–1061. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-8-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaron O, Farhy C, Marquardt T, Applebury M, Ashery-Padan R. Notch1 functions to suppress cone-photoreceptor fate specification in the developing mouse retina. Development. 2006;133:1367–1378. doi: 10.1242/dev.02311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RW. Cell differentiation in the retina of the mouse. Anat Rec. 1985;212:199–205. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092120215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]