Abstract

We identify employees at seven companies whose 401(k) investment choices are dominated because they are contributing less than the employer matching contribution threshold despite being vested in their match and being able to make penalty-free 401(k) withdrawals for any reason because they are older than 59½. At the average firm, 36% of match-eligible employees over 59½ forego arbitrage profits that average 1.6% of their annual pay, or $507. A survey educating employees about the free lunch they are foregoing raised contribution rates by a statistically insignificant 0.67 percent of income among those completing the survey.

Do households make savings and investment mistakes? It is typically difficult to prove that they do, despite widespread concern about household financial literacy (e.g. Campbell, 2006; Bernheim, 1994, 1995, 1998; Lusardi and Mitchell, 2007). The household investment problem is sufficiently complex and economic theory sufficiently rich that few restrictions can be imposed on the range of optimal investment behaviors we should observe. Hence, there is substantial disagreement on important questions about household financial competence, such as whether Americans are under-saving for retirement1 and whether the common practice of holding undiversified portfolios is a mistake.2

But sometimes, incentives are strong enough to create sharp normative restrictions. In this paper, we identify a large class of employees who commonly make choices that are dominated by other options in their choice set. These employees have the following attributes: they are over 59½ years old; they have their 401(k) contributions up to a threshold matched by their employer; those matching contributions are at least partially vested (i.e., the employees can keep at least some of the matching funds even if they immediately separate from the firm); and because they are older than 59½, they can make withdrawals from their 401(k) for any reason without penalty, even while still employed by the firm.

For workers who satisfy these criteria, contributing to the 401(k) at a rate below the match threshold is dominated by a deviation that raises the contribution rate up to the match threshold. The contribution increase triggers instant windfall gains because of the employer match. If the employee then needs access to the additional money contributed, she can withdraw those funds from the plan without penalty and still keep the match.

We calculate a lower bound for money-metric welfare losses from imperfect optimization by computing the difference between the payoff to contributing less than the match threshold and the payoff to the following undominated “contribute and withdraw” strategy: Increase the before-tax 401(k) contribution rate so that total contributions are at the match threshold, and withdraw the additional contribution amounts shortly after they are made from either the before-tax or match account. Relative to the original strategy, the arbitrage raises the employee’s wealth inside the 401(k) plan while leaving her resources outside the plan unaffected.3

We find that at the average firm (equally weighting each firm) in our sample of seven firms, 36% of the match-eligible employees over 59½ years old could gain arbitrage profits using the “contribute and withdraw” strategy because they are contributing less than the match threshold. Under the null hypothesis of rationality and unsatiated utility, none of these employees would be under the match threshold. An employee’s arbitrage losses are bounded above by the total matching contributions available to her. Among employees with a strictly positive loss, the average loss within a firm ranges from 24% to 98% of the employee’s maximum possible arbitrage loss. As a percent of salary, this translates into an average annual loss that ranges from 0.7% ($162) at the company with the least generous match to 2.3% ($782) at the company with the most generous match; the average across companies (equally weighting each company) is 1.6% of annual pay, or $507. There are much larger losses in the right tail. For example, in the company with the most generous match, the largest loss was $7,596 in 1998, or 6.0% of the worker’s salary. We find that substantial losses remain even after accounting for reasonable costs for the time required to execute the “contribute and withdraw” strategy.

Although the “contribute and withdraw” strategy dominates the original policy of contributing less than the match threshold, it may not be the optimal savings strategy. That is why the utility difference between the “contribute and withdraw” strategy and the original strategy is a lower bound on the total utility losses from imperfect optimization. If an employee’s portfolio fails to clear the minimal hurdle of no-arbitrage, the employee may be making other more subtle optimization errors in her consumption and investment choices.

The fact that so many employees in our sample fail to take full advantage of the employer match is especially surprising because one would expect this population to be aware of the benefits of a 401(k) savings plan. Since the people that we study are at least 59½ years old, the need for retirement savings should be salient to them. Having decades of experience managing their money, they should be more financially savvy than their younger counterparts. And at the average company, their mean tenure is 16 years, so they have had ample time to familiarize themselves with their 401(k) plans.

To better understand why older employees do not take full advantage of their 401(k) match, we conducted a field experiment at one of our sample companies with the help of Hewitt Associates, the firm that supplied our 401(k) data. The experiment consisted of randomly assigning employees to receive one of two surveys about their 401(k). The treatment survey contained questions highlighting the foregone match money and the fact that there is no loss of liquidity from contributing up to the match threshold. The control survey did not include these explanatory questions, but was otherwise identical.

The information treatment produced only a small intent-to-treat response, raising the average 401(k) contribution rate by a statistically insignificant 0.10 percentage points of income. Using assignment to the treatment group as an instrumental variable for actually getting treated, we estimate a larger but still statistically insignificant average treatment effect on contribution rates of 0.67 percentage points. We find evidence that employees who are not fully exploiting the employer match are more prone to delay taking other profitable actions than employees at or above the threshold, suggesting that time-inconsistent preferences play some role in undermining optimal investment choices. Survey responses also indicate that direct transactions costs do not explain the failure to contribute to the match threshold. Rather, these individuals appear to have high indirect decision-making costs, as they are much less financially sophisticated and knowledgeable about their firm’s 401(k) plan.

Several previous papers have argued that households fail to exploit apparent arbitrage opportunities. Gross and Souleles (2002) document that some households simultaneously hold high-interest credit card debt and low-interest checking balances, but some have argued that such holdings are not no-arbitrage violations because demand deposits and credit cards are not perfect substitutes, differing in transaction utility and treatment under bankruptcy (Lehnert and Maki, 2002; Zinman, 2007; Bertaut, Haliassos, and Reiter, 2009). Bergstresser and Poterba (2004) and Barber and Odean (2004) identify unexploited tax arbitrage, showing that many households hold heavily taxed assets in taxable accounts and lightly taxed assets in tax-deferred accounts.4 Here also, theoretical research has been divided on whether such allocations are in fact suboptimal (Amromin, 2003; Dammon, Spatt, and Zhang, 2004; Garlappi and Huang, 2006). Amromin, Huang, and Sialm (2007) argue that some U.S. households who pay their mortgages down more quickly than a 30-year amortization schedule requires would be better off saving the prepayment amounts in a tax-deferred account instead, although they note that this strategy is not risk-free because it is vulnerable to factors such as interest rate changes and moving-related mortgage prepayment risks. Warshawsky (1987) highlights unexploited arbitrage opportunities available to individuals with whole life insurance policies who, due to increases in market interest rates subsequent to their policy purchase, could borrow against their policy’s cash value at rates below what they could earn by investing in similarly risky outside assets. But in this case, the extent of such unexploited arbitrage depends on assumptions about the rate of return on other assets, individuals’ access to outside investments of similar risk, individuals’ marginal tax rates, and the amount of measurement error in the survey data used. Relative to this previous work, our 401(k) arbitrage opportunity has the advantage of being theoretically unambiguous and requiring few additional assumptions to identify.

Our paper proceeds as follows. Section I describes our data and the characteristics of the 401(k) plans and employees in our sample. Section II discusses the methodology we use to calculate arbitrage losses in the 401(k) plan. Section III presents the arbitrage loss calculation results. Section IV examines the frequency with which employees forego matching money, whether or not doing so constitutes a no-arbitrage violation. Section V presents the employee and plan correlates of arbitrage losses and foregone match money. Section VI presents the field experiment and discusses potential reasons why individuals are reluctant to contribute up to the match threshold. Section VII concludes.

I. Data Description

A. Data structure

Our data come from Hewitt Associates, a large benefits administration and consulting firm. The sample consists of a year-end 1998 cross-section of all employees at seven firms which span many different industries: consumer products, electronics, health care, manufacturing, technology, transportation, and utilities. We will refer to these firms as Company A through Company G. The cross-section contains employee information such as birth date, hire date, gender, and compensation. It also contains point-in-time information on each employee’s 401(k) on the date of the snapshot, including participation status in the plan, date of first participation, elected contribution rate, and total balances. In addition, the cross-section has annual measures of individual and employer contribution flows into the 401(k) plan.

At Company F, we were able to conduct a field experiment described in Section VI. At this company we have additional cross-sectional snapshots for August 1, 2004 and November 1, 2004. We also have data from surveys mailed during August 2004 to 889 Company F employees over the age of 59½, which we can link to the administrative data.5

B. Sample 401(k) plan rules

We selected our seven sample firms because they offer an employer match and allow employees over the age of 59½ to make withdrawals from their 401(k) balances for any reason (even in the absence of documented financial hardship) without penalty, whether or not they are still employed at the company. Companies are not required to allow withdrawals for workers they still employ, so these firms have made an active decision to permit such in-service withdrawals. There are two potential penalties associated with making a withdrawal, neither of which affectss the “contribute and withdraw” strategy’s payoffs for our sample employees over 59½. First, there is a 10% federal tax penalty levied on individuals under the age of 59½. Second, some companies prohibit employee contributions for a period of time after a withdrawal, which precludes receipt of matching contributions during that time. Our sample firms do not limit future contributions after withdrawals of before-tax and match balances.

Table 1 summarizes the other 401(k) plan rules that are relevant for understanding the payoffs to the “contribute and withdraw” strategy at the seven firms. These can be divided into rules that govern who is allowed to contribute to the plan and in what form, rules that govern the match, and rules that govern withdrawals from the plan.

Table 1.

401(k) Plan rules of seven firms in 1998

| Company A | Company B | Company C | Company D | Company E | Company F | Company G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eligibility to participate |

Only non-union employees after 1,000 hours of service in a year |

January 1 following hire |

Immediate | Non-temporary employees after 1 month of service |

Salaried employees immediate; union employees after 3 months of service |

Immediate | 3 months of service |

|

Contribution types allowed |

Before-tax and after-tax |

Before-tax | Before-tax | Before-tax and after-tax |

Before-tax and after- tax |

Before-tax and after-tax |

Before-tax (aftertax allowed only under a prior regime) |

|

Employer match rate |

50% match on first 4% of pay contributed |

25% match on first 3% of pay contributed (before-tax contributions only) |

100% match on first 3% of pay contributed; 50% match on next 3%. No match in 1st service year. |

75% match on first 2% of pay contributed; 50% match on next 3% contributed |

20% to 35% match on first 6% of pay contributed, depending on employee group |

25% to 100% match on first 6% of pay contributed, depending on employee group |

100% match on first 3% of pay contributed; 50% match on next 3% contributed |

|

Match invested in employer stock |

No | No | No | Yes; diversification restricted if < 50 years old |

Yes; diversification restricted |

Yes; diversification restricted |

Yes; diversification restricted |

| Vesting schedule | 5-year cliff, or 100% at age 65 |

5-year graded from 3 to 7 years of tenure, or 100% at age 65 |

4-year graded from 2 to 5 years of tenure, or 100% at age 60 |

5-year cliff, or 100% upon retirement at or after age 55 |

5-year graded from 1 to 5 years of tenure |

5-year cliff | Immediate |

|

Withdrawal restrictions for employees older than 59½ |

No restrictions | Matching contributions not available for withdrawal until termination of employment |

Order of account depletion: rollover, before-tax, match |

1-year contribution suspension after withdrawals from matched after-tax dollars. Can withdraw match only if the money has been in plan for 2 years |

$100 minimum; no more than 6 per year. Order of account depletion: after-tax, before-tax, match |

$250 minimum; no more than 1 per month. Order of account depletion: after-tax, match, before-tax |

No more than 1 per month. Order of account depletion: after-tax, match dollars that have been in plan for more than 2 years, rollover, before-tax |

|

Withdrawal procedures |

Call toll-free number. Checks cut within 2 business days |

Call toll-free number. Checks mailed in 2–3 weeks |

Call toll-free number. Check processing time not in documents |

Call toll-free number. Withdraw- als processed within 1 week |

Call toll-free number. Check processing time not in plan documents |

Call toll-free number. Checks mailed next week |

Call toll-free number. Check processing time not in plan documents |

Note: This table shows the 401(k) plan rules at our sample firms as of 1998, according to the firms’ plan documents.

Most employees at these firms are eligible to participate in the 401(k) plan either immediately after hire or after a short waiting period. At Company A, union employees are excluded from the plan. Eligible employees at all firms can make contributions using before-tax money, and some firms also allow contributions using after-tax money.

The maximum gain from the match in our sample is 6% of annual salary for certain employees at Company F who are matched at a 100% rate for the first 6% of their pay contributed to the 401(k) plan. Company B offers the smallest potential gain of 0.75% of annual salary, as it only matches 25 cents per dollar for the first 3% of pay contributed. Four of the firms in our sample (Companies D, E, F, and G) invest the match in employer stock and restrict diversification of match balances. These restrictions are lifted for Company D employees age 50 and over. In the remaining three companies, restrictions apply even for those over age 59½, but diversification is not entirely prohibited. Company E allows salaried employees to diversify half of the match after age 55 or five years of service at the company. Company F employees who have participated in the plan for five years can completely diversify money that has been in the plan for at least two years. And Company G allows complete diversification of money that has been in the plan for at least two years.

Employees do not have access to their employer match money until it is vested. If an employee is only 80% vested when he leaves the company, he forfeits 20% of the balances accrued in his match account. If the employer allows withdrawals from the match account while the employee is still working at that firm, the employee can only withdraw the vested amount. In our sample of firms, the fraction of match money vested is a function of an employee’s tenure at the company (and not time since a specific contribution was made to the 401(k) plan).6 For example, once an employee crosses the tenure requirement for 60% vesting, all of her existing match balances are immediately 60% vested, and new matching contributions going forward will also be 60% vested.

Matching contributions at Company G are fully vested from the first day of an employee’s tenure. Companies B, C, and E use a graded vesting schedule in which the fraction of match balances vested increases gradually with years of service until the employee is 100% vested. For instance, employees at Company B are 0% vested until the end of their second year at the company. At the beginning of their third year at the company, they are 20% vested, and their vesting percentage increases by 20% at the beginning of each subsequent year until they are 100% vested at the beginning of their seventh year. In contrast, Companies A, D, and F have cliff vesting schedules in which employees are not vested at all before achieving five years of tenure and are 100% vested thereafter. Four of the companies with graded or cliff vesting schedules fully vest employees who reach a certain age even if they would not be fully vested based on their tenure alone (Companies A, B, C, and D).

With the exception of Company A, our sample firms impose some restrictions on withdrawals from the 401(k) while a worker is still employed at the firm. Only some of these restrictions affect the “contribute and withdraw” strategy. At Company E, accounts must be depleted in the following order: after-tax balances, before-tax balances, and finally match balances. That is, accounts earlier in the order must be completely empty before accounts later in the order can be accessed. At Company F, the mandated order is after-tax, match, and finally before-tax balances. At Company G, the mandated order is after-tax balances, match balances that have been in the plan for more than two years, rollover balances, and finally before-tax balances; match balances that have been in the plan for less than two years may not be withdrawn. Companies E, F, and G also impose withdrawal frequency restrictions that cap withdrawals at either six or twelve per year. Companies E and F respectively impose a $100 and $250 minimum withdrawal amount. We discuss the impact of the withdrawal order rules in Section II, and the impact of the withdrawal frequency and amount restrictions in Section III.B.

All seven firms allow participants to request withdrawals by calling a toll-free number. Four of our firms specify in their plan documents how quickly withdrawal checks are issued. Three issue them within one week of the request, and the fourth mails checks in two to three weeks.

C. Sample employee characteristics

Table 2 reports summary employee characteristics as of year-end 1998 for the 5,045 active employees in our sample who were older than 59½ at the beginning of 1998, eligible to receive matching contributions in 1998, and whose 1998 salary exceeded that of a full-time worker earning the federal minimum wage.7 For the sake of comparison, we also present employee attributes for the match-eligible population younger than 59½ earning more than the salary cutoff at these firms. Our sample generally has a male worker majority, but includes one firm (Company B) that is predominantly female. Firm-level median salary among older workers ranges from $11,829 to $57,788, and median 401(k) balance among plan participants also exhibits considerable dispersion from $7,635 to $117,151. At most firms, the average tenure among older workers is greater than 12 years, but at Company A, this average is 5.9 years.

Table 2.

Employee characteristics of seven firms at year-end 1998

| Company A | Company B | Company C | Company D | Company E | Company F | Company G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total active employees | Over 4,000 | Over 50,000 | Over 10,000 | Over 20,000 | Over 30,000 | Over 20,000 | Over 10,000 |

| Match-eligible employees older than 59½ | |||||||

| Number of employees | 537 | 2,084 | 242 | 383 | 841 | 816 | 142 |

| Fraction male (%) | 82.7% | 16.7% | 58.9% | 73.3% | 65.2% | 91.7% | 70.4% |

| Average age (years) | 68.2 | 64.4 | 63.6 | 62.7 | 63.0 | 62.6 | 62.6 |

| Average tenure (years) | 5.9 | 14.9 | 12.1 | 22.5 | 22.2 | 16.0 | 18.4 |

| Median salary | $11,829 | $24,705 | $43,711 | $40,830 | $45,812 | $32,444 | $57,788 |

| Fraction who have ever enrolled in the 401(k) |

72.6% | 64.0% | 97.1% | 92.2% | 84.5% | 90.7% | 98.6% |

| Fraction contributing to 401(k) at year-end 1998 |

33.3% | 51.2% | 90.1% | 88.3% | 79.5% | 82.8% | 97.2% |

| Median 401(k) balance of participants |

$7,635 | $16,259 | $69,440 | $117,151 | $90,983 | $46,830 | $47,382 |

| Match-eligible employees younger than 59½ | |||||||

| Fraction male | 49.5% | 19.1% | 66.0% | 70.6% | 65.7% | 81.7% | 76.9% |

| Average age (years) | 38.2 | 41.3 | 39.2 | 42.3 | 43.2 | 43.7 | 44.0 |

| Average tenure (years) | 5.5 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 14.1 | 15.3 | 10.9 | 17.7 |

| Median salary | $23,229 | $29,267 | $44,932 | $38,605 | $46,854 | $32,326 | $62,111 |

| Fraction who have ever enrolled in the 401(k) |

64.2% | 57.9% | 88.5% | 92.8% | 86.7% | 86.2% | 99.6% |

| Fraction contributing to 401(k) at year-end 1998 |

44.9% | 46.6% | 79.9% | 85.0% | 83.7% | 81.1% | 96.7% |

| Median 401(k) balance of participants |

$11,521 | $9,136 | $31,669 | $45,215 | $52,951 | $30,258 | $53,078 |

Note: The sample for all rows but the first is employees who are eligible to receive a 401(k) matching contribution in 1998 and whose 1998 salary is more than that of a full-time minimum wage worker. The first row includes all employees at each company, whether or not they meet the eligibility and salary requirements. We sort employees into age subsamples based on their age on January 1, 1998. However, all statistics are reported as of year-end 1998. To maintain the confidentiality of the companies analyzed, we report only the approximate number of total active employees, and we do not report the number of employees under the age of 59½.

At the average firm, 86% of employees over 59½ have enrolled in the 401(k), and 75% made a 401(k) contribution in the last pay cycle of 1998. The analogous averages for employees under 59½ are 82% and 74%, respectively. As a point of comparison, 63% of all eligible U.S. workers were participating in a 401(k) or 403(b) plan in 1998 (Copeland, 2009).

II. Arbitrage Loss Calculation Methodology

For an employee contributing less than the match threshold, the “contribute and withdraw” strategy consists of raising his before-tax contribution rate so that total contributions are at the match threshold, and then withdrawing this extra contribution amount shortly afterwards from the before-tax or match account. Withdrawals from before-tax and match 401(k) balances are taxed at the ordinary income tax rate on the entire withdrawal. Thus, under our strategy, when the incremental contribution is withdrawn, its entirety is taxed as ordinary income. If the employee were to continue contributing less than the match threshold, the incremental contribution amount would have been immediately taxed as ordinary income anyway. Therefore, the strategy does not affect the employee’s current tax liability.8

To calculate arbitrage losses, we start with the difference between the maximum possible matching contributions individuals could have received in 1998 and the match they actually received.9 This difference represents the additional 401(k) balances they would have accrued (before capital gains) by following the “contribute and withdraw” strategy. We then make a few adjustments to this number to arrive at our final arbitrage loss figures.

Not being vested can eliminate the arbitrage gains from contributing up to the match threshold. If an employee is not vested and knows that she will leave the company before becoming even partially vested, the employer match is worth nothing to her.10 On the other hand, the employer match should be fully valued if the currently unvested employee is completely confident that she will stay at the company until she is fully vested. In practice, incomplete vesting does not significantly affect our calculation of arbitrage losses because almost all sample employees over 59½ years old are fully vested as of January 1, 1998. We handle the small fraction of employees who are not fully vested in the following way.

Because we do not know each unvested employee’s subjective probability of leaving the company before becoming vested, we adopt a conservative approach. The loss from not contributing up to the employer match threshold is calculated as the employer match foregone multiplied by the employee’s vested percentage at the time of the contribution.11 For example, consider an employee in a firm with a dollar-for-dollar (100%) match up to 5% of pay whose vesting percentage increases from 0% to 20% on July 1, 1998. In calculating the arbitrage losses in calendar year 1998, we do not include any foregone matching contributions prior to July 1, 1998. After this date, when the employee’s vesting percentage increases to 20%, her calculated losses are only 20% of the foregone employer match. So if this employee contributed 2% of her salary every pay period, then her arbitrage losses for the year as a fraction of her annual salary would be defined as

Note that this calculation will understate expected losses by ignoring all continuation values from receiving the match. In unreported results, we find that calculating ex post losses using the employee’s actual subsequent employment history at the company yields numbers that are only slightly greater.12 The results are similar because almost all sample employees over 59½ years old are fully vested.

In some of our companies, employees can contribute to the 401(k) using after-tax dollars. Withdrawals from after-tax balances are taxed only on accumulated capital gains. Therefore, if one has after-tax balances, the ability to shift withdrawals from those balances into years when one’s marginal tax rate is high is a potentially valuable option.13 At Companies E, F, and G, after-tax 401(k) balances must be depleted first when withdrawing money from the plan.14 Executing the “contribute and withdraw” strategy at these companies would require withdrawing after-tax balances in the current year, eliminating the option to delay those withdrawals.

Only 17% of employees older than 59½ who contribute less than the match threshold at these three firms have after-tax 401(k) balances. In order to avoid having to calculate the loss caused by early withdrawals from the after-tax account, we simply do not attribute arbitrage losses to anybody at Companies E, F, and G who had a positive balance in her after-tax account at year-end 1998, regardless of her 401(k) contribution rate. This conservative assumption leads us to understate the fraction of employees who are foregoing a free lunch.

Companies E, F, and G also invest their match balances in employer stock and restrict diversification for employees older than 59½. This constraint is not binding at Companies E and F because their employees are allowed to withdraw match balances, and the match can be converted to cash upon withdrawal.15 The constraint does bind at Company G, which does not allow diversification or withdrawal of match balances held in the plan for less than two years. A match in employer stock is worth less than a match that can be diversified.16 However, it is not clear how large the bias is, since employees can sell employer stock short in a non-401(k) account, so a sophisticated employee could hedge herself against its idiosyncratic risk. We do not make further adjustments to the arbitrage losses calculated for Company G’s employees, but note that their loss magnitudes may be somewhat overstated.

Finally, to allow for the possibility of rounding error, we do not classify an employee as failing to fully exploit the employer match if her calculated arbitrage loss is less than 0.1% of annual income.

III. Frequency and Magnitude of Arbitrage Losses

A. Baseline results

Table 3 reports the frequency and magnitude of unexploited 401(k) arbitrage in 1998. At the average company in our sample, 36% of match-eligible employees over 59½ did not receive the full employer match despite being at least partially vested and not having after-tax balances that must be depleted before before-tax balances can be withdrawn. The most an individual can lose due to unexploited arbitrage is the total matching contribution available to him that immediately vests. At Company B, which offers the smallest match, the upper bound is 0.75% of salary. At the other extreme, Company F offers a match as large as 6% of salary for some of its employees. Among those with arbitrage losses, the average loss as a fraction of the maximum potential loss ranges from 24% to 98%; the cross-company average is 68%. Conditional on having a loss, the average loss ranges from 0.66% of salary ($162) at Company B to 2.32% of salary ($782) at Company F; the cross-company average is 1.57% ($507).17 The proportion lost relative to the maximum possible loss is driven largely by the fraction of employees who contributed nothing at all. Companies C and G are notable for having a relatively small number of non-participants; at the other five companies, at least half of those with arbitrage losses gave up the entire match.

Table 3.

Arbitrage losses in 1998: employees over age 59½

| Company A | Company B | Company C | Company D | Company E | Company F | Company G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number with arbitrage losses | 320 | 973 | 113 | 78 | 263 | 196 | 36 |

| Fraction of sample who have arbitrage losses | 59.6% | 46.7% | 46.7% | 20.4% | 31.3% | 24.0% | 25.4% |

| Maximum possible loss as a fraction of pay Among those with arbitrage losses: |

2% | 0.75% | 4.5% | 3% | 1.2 to 2.1% | 1.5 to 6% | 4.5% |

| Average fraction of maximum possible loss realized | 97.5% | 96.8% | 34.2% | 69.2% | 81.4% | 72.4% | 23.7% |

| Fraction contributing nothing | 95.0% | 93.7% | 21.2% | 73.1% | 69.6% | 54.1% | 11.1% |

| Among those contributing nothing, fraction who have never enrolled in the 401(k) |

34.2% | 71.0% | 25.0% | 52.7% | 71.0% | 38.6% | 50.5% |

| Average loss, percent of annual pay | 1.71% | 0.66% | 1.53% | 2.07% | 1.63% | 2.32% | 1.07% |

| Average loss, $ | $215 | $162 | $642 | $722 | $677 | $782 | $350 |

| Distribution of losses as a percent of annual pay ($) | |||||||

| Maximum | 2.00% ($947) |

0.75% ($1,200) |

4.50% ($6,357) |

3.00% ($2,651) |

2.10% ($3,360) |

6.00% ($7,596) |

4.50% ($1,182) |

| 95th percentile | 2.00% ($379) |

0.75% ($367) |

4.50% ($2,192) |

3.00% ($1,560) |

2.10% ($1,756) |

4.45% ($1,521) |

4.50% ($1,168) |

| 90th percentile | 2.00% ($320) |

0.75% ($291) |

4.50% ($1,650) |

3.00% ($1,397) |

2.10% ($1,412) |

3.00% ($1,098) |

4.50% ($1,004) |

| 75th percentile | 2.00% ($252) |

0.75% ($195) |

2.62% ($953) |

3.00% ($1,048) |

2.10% ($859) |

3.00% ($938) |

1.44% ($489) |

| Median | 2.00% ($204) |

0.75% ($134) |

0.51% ($268) |

3.00% ($662) |

2.10% ($582) |

2.51% ($747) |

0.25% ($121) |

| 25th percentile | 1.57% ($181) |

0.75% ($89) |

0.17% ($65) |

0.88% ($262) |

1.05% ($257) |

1.50% ($429) |

0.17% ($80) |

| 10th percentile | 0.75% ($93) |

0.31% ($66) |

0.17% ($50) |

0.41% ($126) |

0.37% ($173) |

0.91% ($262) |

0.17% ($60) |

| 5th percentile | 0.42% ($42) |

0.22% ($42) |

0.17% ($47) |

0.24% ($89) |

0.33% ($106) |

0.45% ($132) |

0.17% ($48) |

| Minimum | 0.11% ($11) |

0.10% ($11) |

0.11% ($33) |

0.10% ($36) |

0.15% ($41) |

0.13% ($40) |

0.17% ($47) |

Note: The sample is employees age 59½ and older on January 1, 1998 who are eligible to receive a 401(k) matching contribution and whose 1998 salary is more than that of a full-time minimum wage worker. Arbitrage losses arise from not contributing at least to the match threshold, being at least partially vested in the match, and not having after-tax balances that must be depleted before other balances can be withdrawn.

The bottom half of Table 3 shows the distribution of arbitrage losses, both in absolute dollars and as a percent of pay, among those whom we classify as having an arbitrage loss.18 In companies with a generous match, the losses at the right tail of the distribution are considerable. For example, the 75th percentile arbitrage losses at Companies C, D, and F are around $1,000 and 3% of salary. At the 90th percentile, arbitrage losses at Company E and G also exceeded $1,000, or 2.1% and 4.5% of salary, respectively. The maximum dollar arbitrage loss ranges from $947 (2% of salary) at Company A to $7,596 (6% of salary) at Company F.

The absolute dollar losses in Table 3, which are calculated over only one year, are likely to be much smaller than the cumulative absolute dollar losses over time. Among those who contributed nothing to their 401(k) plan in 1998, 49% at the average company are not enrolled in the plan, which means that they have never contributed to the plan, thus giving up matching contributions during their entire tenure with the company. We do not attempt an exact calculation of cumulative losses for all employees because doing so would require information on 401(k) eligibility, the 401(k) match, employee compensation, and employee contribution rates for many years before 1998, which we do not have. But a simple extrapolation from Table 3 suggests that substantial cumulative losses are probable for many of these individuals.

B. Accounting for the time costs of the “contribute and withdraw” strategy

We have so far ignored the cost of the time required to execute the “contribute and withdraw” strategy. If this cost is large, it could wipe out the potential arbitrage gains. In this subsection, we estimate arbitrage profits net of time costs.

In the survey described in Section VI, respondents who had already enrolled in their 401(k) reported spending 1.4 hours on average doing so. Respondents who had made further transactions in their 401(k) reported spending 0.6 hours on average to change either their contribution rate or asset allocation for the very first time. If taking a withdrawal from the plan is as time-consuming as changing one’s asset allocation or contribution rate for the first time and does not get faster as the employee gains experience, then a non-participant would spend 8.6 hours on average in the first year of the “contribute and withdraw” strategy enrolling in the plan and then withdrawing his contributions once a month; a current plan participant would spend 7.8 hours on average increasing his contribution rate to the match threshold and then withdrawing monthly.

Taking these numbers as a baseline, we consider a range of annual time requirements for executing the “contribute and withdraw” strategy: three, six, and twelve hours per year. We also consider two different assumptions about the value of this time: the hourly wage, and half the hourly wage. Neoclassical labor supply theory suggests the value of the marginal hour is the wage rate. The literature on travel costs finds on average that time spent commuting is valued at about 50 percent of the wage rate (Small, 1992). Since we do not have information on weekly hours or hourly wages, we divide annual salary by 1,750 yearly hours to approximate the hourly wage.

Table 4 shows that at all companies, under the most conservative estimate of the “contribute and withdraw” strategy’s time cost (three hours at half the hourly wage rate), the fraction of our sample with net arbitrage losses is the same as the fraction with arbitrage losses ignoring time costs, although the average size of the net arbitrage losses conditional on having a net loss is slightly smaller (between $10 and $37). As we increase either the time required or the value of a marginal hour, the fraction of the sample with net arbitrage losses falls. But even under our most aggressive assumptions about the time cost (twelve hours at the hourly wage rate), 26% of older employees at the average firm continue to have net arbitrage losses averaging $476.

Table 4.

Incidence of arbitrage losses net of time costs in 1998: employees over age 59½

| Company A | Company B | Company C | Company D | Company E | Company F | Company G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (from Table 3) | 59.6% ($215) |

46.7% ($162) |

46.7% ($642) |

20.4% ($722) |

31.3% ($677) |

24.0% ($782) |

25.4% ($350) |

| Value of marginal hour = ½ hourly wage | |||||||

| 3 hours annually to execute arbitrage | 59.6% ($205) |

46.7% ($140) |

46.7% ($606) |

20.4% ($692) |

31.3% ($642) |

24.0% ($754) |

25.4% ($313) |

| 6 hours annually to execute arbitrage | 58.8% ($196) |

45.1% ($124) |

36.8% ($723) |

19.8% ($680) |

31.0% ($611) |

23.7% ($738) |

12.7% ($554) |

| 12 hours annually to execute arbitrage | 57.5% ($179) |

41.2% ($91) |

25.6% ($955) |

18.8% ($657) |

29.3% ($573) |

23.2% ($697) |

12.0% ($513) |

| Value of marginal hour = hourly wage | |||||||

| 3 hours annually to execute arbitrage | 58.8% ($196) |

45.1% ($124) |

36.8% ($723) |

19.8% ($680) |

31.0% ($611) |

23.7% ($738) |

12.7% ($554) |

| 6 hours annually to execute arbitrage | 57.5% ($179) |

41.2% ($91) |

25.6% ($955) |

18.8% ($657) |

29.3% ($573) |

23.2% ($697) |

12.0% ($513) |

| 12 hours annually to execute arbitrage | 54.4% ($145) |

36.1% ($15) |

21.1% ($998) |

15.9% ($644) |

26.3% ($489) |

22.2% ($613) |

10.6% ($428) |

Note: This table shows the fraction of the sample that suffered arbitrage losses in 1998 exceeding the time costs of executing the “contribute and withdraw” strategy under various assumptions about the value of the marginal hour and the number of hours per year it takes to execute the strategy. In parentheses are the average dollar arbitrage losses net of time costs, conditional on having a positive net arbitrage loss. The sample is employees who are age 59½ and older on January 1, 1998, eligible to receive a 401(k) matching contribution in 1998, and whose 1998 salary is more than that of a full-time minimum wage worker. Arbitrage losses arise from not contributing at least to the match threshold, being at least partially vested in the match, and not having after-tax balances that must be depleted before other balances can be withdrawn. Hourly wage is computed by dividing annual salary by 1,750 hours.

Time costs can be substantially reduced by withdrawing less frequently—e.g., once every three months rather than every month. Little efficiency is lost by this modification because the implicit financing costs of infrequent withdrawals are small. Even if the cost of capital is a typical credit card interest rate of 15%, an employee with a $50,000 annual salary will pay only $14 per quarter to borrow the funds necessary to finance a 6% increase in his 401(k) contribution rate.19 If the cost of capital is the foregone after-tax earnings in a money market account (5% interest), the cost is about $3 per quarter. Small carrying costs also imply that the maximum withdrawal frequency restrictions, minimum withdrawal amounts (which, if binding, can be dealt with by reducing the frequency of withdrawals), and check processing delays listed in the penultimate row of Table 2 do not substantially reduce arbitrage profits.

IV. Frequency and Magnitude of Foregone Match Money

Table 5 displays calculations similar to those in Table 3 (which does not account for time costs), but using a much simpler loss definition. In Table 5, we include the full amount of any matching contribution foregone, without regard to the employee’s age, vesting status, or after-tax account balances.20 Note that the arbitrage losses in Table 3 are a strict subset of the matches foregone in Table 5.

Table 5.

Foregone employer matching contributions in 1998

| Company A | Company B | Company C | Company D | Company E | Company F | Company G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Match-eligible employees older than 59½ | |||||||

| Number contributing less than match threshold | 386 | 1,088 | 114 | 78 | 267 | 246 | 51 |

| Fraction of ≥ 59½ sample contributing less than match threshold |

71.9% | 52.2% | 47.1% | 20.4% | 31.7% | 30.1% | 35.9% |

| Among those below the threshold: | |||||||

| Average fraction of maximum possible match foregone |

96.5% | 96.6% | 33.9% | 69.2% | 80.6% | 74.0% | 20.2% |

| Fraction contributing nothing | 93.5% | 93.5% | 21.1% | 73.1% | 68.5% | 56.9% | 7.8% |

| Among those contributing nothing, fraction who have never enrolled in the 401(k) |

40.7% | 73.6% | 25.1% | 52.7% | 71.1% | 53.6% | 50.0% |

| Average match foregone, percent of annual pay | 1.73% | 0.72% | 1.52% | 2.07% | 1.67% | 2.38% | 0.91% |

| Average match foregone, $ | $221 | $180 | $638 | $722 | $693 | $768 | $313 |

| Match-eligible employees younger than 59½ | |||||||

| Fraction of < 59½ sample contributing less than match threshold |

70.6% | 61.8% | 66.2% | 30.6% | 37.1% | 37.3% | 46.9% |

| Among those below the threshold: | |||||||

| Average match foregone as percent of maximum available match |

87.8% | 93.8% | 46.0% | 67.9% | 69.7% | 69.6% | 23.2% |

| Fraction contributing nothing | 77.5% | 86.4% | 30.4% | 60.2% | 48.8% | 50.7% | 7.1% |

| Among those contributing nothing, fraction who have never enrolled in the 401(k) |

63.9% | 78.8% | 56.9% | 39.0% | 73.0% | 72.0% | 12.7% |

| Average match foregone, percent of annual pay | 1.44% | 0.70% | 2.06% | 2.04% | 1.40% | 2.53% | 1.04% |

| Average match foregone, $ | $340 | $194 | $907 | $726 | $629 | $840 | $533 |

Note: The sample is all employees eligible to receive a 401(k) matching contribution in 1998 and whose 1998 salary is more than that of a full-time minimum wage worker. The ages used to sort employees into subsamples are computed as of January 1, 1998. To maintain the confidentiality of the companies analyzed, we do not report the number of employees under the age of 59½.

We present Table 5 for two reasons. First, we would like to compare the behavior of employees older than 59½ to that of employees younger than 59½. However, the “contribute and withdraw” strategy is largely infeasible for employees younger than 59½ because they must demonstrate financial hardship in order to withdraw money from their 401(k).21 Thus, the arbitrage losses calculated in Table 3 for employees older than 59½ do not extend in a straightforward way to younger workers. We can, however, simply compare the total matching contributions foregone by older and younger employees. Second, other 401(k) datasets may not contain all of the information needed to calculate arbitrage losses as we have here. The simpler measure in Table 5 allows for easier comparison of this paper’s results with tabulations from other data sources.

The top half of Table 5 presents statistics on employees older than 59½. At the average company, 41% of employees over 59½ contribute below the match threshold, foregoing an average of 1.6% of their salary, or $505. Matches foregone are similar to arbitrage losses because most older employees under the match threshold can unambiguously profit from the “contribute and withdraw” strategy; almost all are fully vested in the employer match, and only a small minority have after-tax balances that must be depleted before before-tax withdrawals are allowed.

The bottom half of Table 5 presents statistics on match-eligible employees younger than 59½. Interestingly, the fraction of employees contributing below the match threshold is generally similar among employees under age 59½ and employees over age 59½, differing by no more than 11 percentage points, with the exception of Company C. There is, however, one notable difference: employees younger than 59½ under the match threshold are more likely to be contributing something to the 401(k), whereas older employees under the match threshold are more prone to be contributing nothing at all. There is no systematic tendency for younger employees under the threshold to forego more match dollars as a percent of their salary than older employees under the threshold. However, the absolute dollar amounts forfeited by younger employees under the threshold are usually higher.

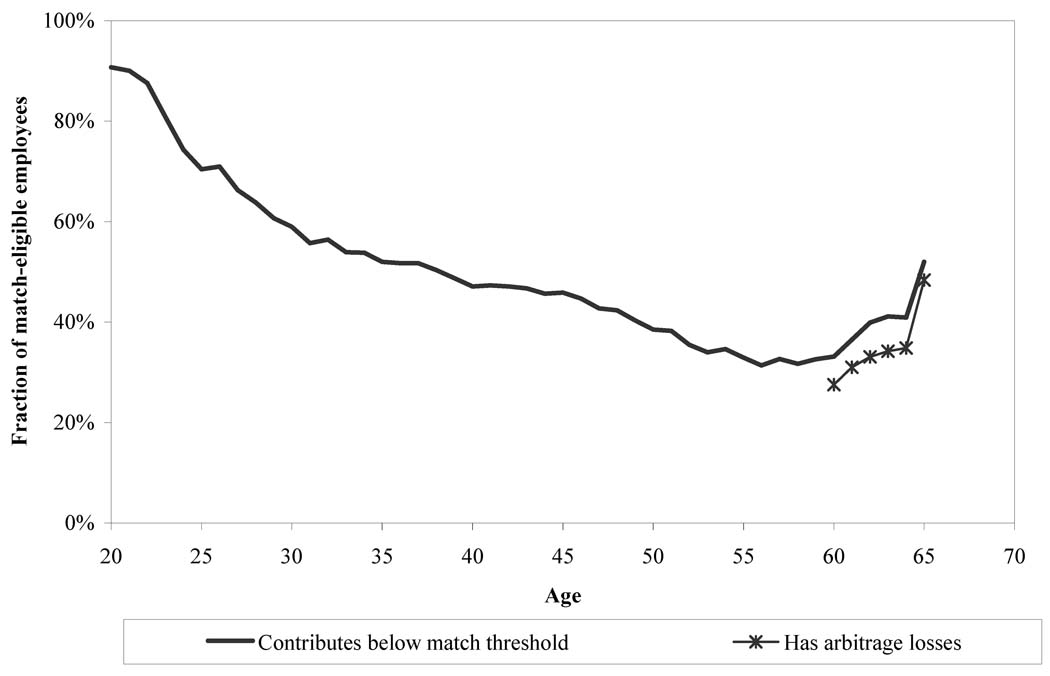

In Figure 1, we pool all of the match-eligible employees in our seven companies and plot, by age, the fraction of employees over the age of 59½ with arbitrage losses, as well as the fraction of employees at all ages who contribute below the match threshold. Consistent with the results in Table 3 and Table 5, these two series are similar for employees above age 59½. Over the entire working life, the likelihood of contributing below the match threshold is U-shaped, declining with age until the mid-50s and increasing afterwards. Interestingly, this pattern mirrors the finding in Agarwal et al. (2009) that the quality of financial decision making peaks in the 50s in a variety of other domains (e.g., credit card and mortgage choices). One might have expected a discrete drop in the likelihood of contributing below the match threshold at age 59½, when the 401(k) essentially becomes a liquid asset. It is thus surprising that the failure to exploit the match is increasing at the age when the economic reasons for 401(k) participation become most compelling.22 The increase may arise from a selection effect generated by low savers who are less able to afford to retire and thus remain in the labor force longer. Alternatively, this phenomenon may reflect consumption smoothing by older employees whose wages are falling and who are unaware of the 401(k) withdrawal privileges available only to older workers. (Table 2 shows that the older employees at our firms usually have a lower median wage than their younger counterparts.)

Figure 1. Failure to Fully Exploit the 401(k) Match in 1998, by Age.

Note: This graph shows, by age, the fraction of match-eligible employees who either contributed below the match threshold or who had positive arbitrage losses in 1998. Employees in all seven sample firms are pooled in this graph.

V. Correlates of Arbitrage Losses and Foregone Match Money

In this section, we explore the individual and plan characteristics that are correlated with arbitrage losses (for employees older than 59½) or foregone match money. We consider four different dependent variables: a dummy for having any arbitrage loss, a dummy for contributing below the match threshold, the size of an individual’s arbitrage loss as a percent of pay, and the size of an individual’s foregone matching contributions as a percent of pay.

Table 6 shows regression results that control for gender, marital status, log of tenure at the firm, log of salary, age dummies, and firm fixed effects. We pool the match-eligible employees in our seven firms and run separate regressions for employees over 59½ and employees under 59½. The regressions with binary dependent variables (having an arbitrage loss or contributing below the match threshold) are probits for which marginal effects at the sample means are reported; the other regressions (arbitrage losses or foregone matching contributions as a percent of salary) are tobits where the dependent variable is censored below at 0% and above at the maximum possible value for each employee.23

Table 6.

Predictors of arbitrage losses or foregone employer matching contributions in 1998, including plan fixed effects

| Employees older than 59½ |

Employees younger than 59½ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has arbitrage losses |

Contributes < match threshold |

Arbitrage losses (% of salary) |

Matching contributions foregone (% of salary) |

Contributes < match threshold |

Matching contributions foregone (% of salary) |

|||

| Male | 0.129** | 0.133** | 0.723** | 0.706** | Male | 0.063** | 0.277** | |

| (0.019) | (0.020) | (0.111) | (0.106) | (0.003) | (0.015) | |||

| Married | −0.066** | −0.083** | −0.401** | −0.436** | Married | −0.047** | −0.270** | |

| (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.095) | (0.092) | (0.003) | (0.014) | |||

| Log(Tenure) | 0.041** | −0.093** | 0.147* | −0.361** | Log(Tenure) | −0.091** | −0.397** | |

| (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.062) | (0.052) | (0.002) | (0.008) | |||

| Log(Salary) | −0.348** | −0.373** | −1.775** | −1.838** | Log(Salary) | −0.354** | −1.623** | |

| (0.016) | (0.017) | (0.097) | (0.093) | (0.003) | (0.016) | |||

| Age = 60 | 0.022 | 0.027 | 0.170 | 0.152 | Age 20–29 | −0.143** | 0.018 | |

| (0.025) | (0.026) | (0.146) | (0.139) | (0.036) | (0.124) | |||

| Age = 61 | 0.028 | 0.036 | 0.308* | 0.305* | Age 30–39 | −0.160** | −0.054 | |

| (0.027) | (0.028) | (0.155) | (0.147) | (0.037) | (0.124) | |||

| Age = 62 | 0.025 | 0.049 | 0.361* | 0.333* | Age 40–49 | −0.152** | −0.025 | |

| (0.030) | (0.031) | (0.172) | (0.163) | (0.037) | (0.124) | |||

| Age = 63 | 0.015 | 0.011 | 0.109 | 0.042 | Age 50–59½ | −0.216** | −0.376** | |

| (0.033) | (0.033) | (0.186) | (0.178) | (0.035) | (0.125) | |||

| Age = 64 | 0.145** | 0.088* | 0.559** | 0.487* | ||||

| (0.038) | (0.039) | (0.207) | (0.200) | |||||

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.213** | 0.123** | 0.805** | 0.670** | ||||

| (0.028) | (0.029) | (0.156) | (0.148) | |||||

| Sample size | 5,043 | 5,043 | 4,395 | 5,043 | Sample size | 158,894 | 158,894 | |

Note: This table presents the results of regressions with one of four dependent variables: (1) a binary indicator for whether an employee had arbitrage losses, (2) a binary indicator for whether an employee contributed less than the match threshold, (3) arbitrage losses as a percent of salary, and (4) matching contributions foregone as a percent of salary. Regressions with binary dependent variables are probits, and regressions with continuous dependent variables are tobits censored below at 0% and above at the maximum possible value for each individual. The sample is restricted to employees eligible for their 401(k) match and whose 1998 salary is more than that of a full-time minimum wage worker. The sample for the arbitrage loss as a percent of pay regression is further restricted to exclude participants who contribute below the match threshold but whom we do not categorize as having arbitrage losses due to their after-tax balances or vesting status. The ages used to sort employees into subsamples are computed as of January 1, 1998. The explanatory variables are a male dummy, a married dummy, the participant’s age on January 1, 1998, the log of the number of years since the participant’s original hire date as of December 31, 1998, and the log of the participant’s salary in 1998. Firm fixed effects are included, although their coefficients are not reported. For the probit regressions, the point estimates are marginal effects evaluated at the means of the explanatory variables; the marginal effect reported for dummy variables is the effect of changing the variable from 0 to 1. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Significant at the 5% level.

Significant at the 1% level.

We find that among over-59½ year olds, men are 13 percentage points more likely to have an arbitrage loss, the married are 7 percentage points less likely to have an arbitrage loss, and a 1 percent increase in salary is associated with a 0.35 percentage point decrease in the likelihood of having an arbitrage loss. A 1% increase in tenure is associated with a 0.04 percentage point increase in the likelihood of having an arbitrage loss, since at six of our seven companies, having very low tenure means one is completely unvested and thus never classified as having an arbitrage loss. There is no significant age gradient in the probability of arbitrage losses from age 59 to 63, but the incidence of arbitrage losses is 15 percentage points higher among 64 year olds than 59 year olds, and 21 percentage points higher among those at least 65 years old than among 59 year olds. The results are directionally similar when arbitrage loss as a percent of salary is the dependent variable. Males have a latent (uncensored) loss as a percent of salary that is larger by 0.7 percentage points, the married have a loss that is smaller by 0.4 percentage points, a 1% increase in tenure is associated with a loss that is larger by 0.001 percentage points, a 1% increase in salary is associated with a loss that is smaller by 0.02 percentage points, and losses are generally increasing in age.

When the dependent variable is an indicator for simply contributing less than the match threshold, the coefficients on the explanatory variables are mostly similar to those when the dependent variable is an indicator for having arbitrage losses. The one exception is log tenure, which positively predicts the probability of having an arbitrage loss but negatively predicts the likelihood of contributing less than the threshold. This difference is driven by the tenure-based vesting rules, which affect the arbitrage loss calculations but not the classification of whether an employee is contributing less than the match threshold. The regression of matching contributions foregone as a percent of salary exhibits similar patterns with respect to the regression of arbitrage losses as a percent of salary.

Turning to the sample of under-59½ year olds, we find that the coefficients of most variables are qualitatively similar for employees above and below 59½ years of age. Among younger employees, being male, unmarried, recently hired, and low-salaried increase the likelihood of contributing less than the match threshold. The variable with qualitatively different results is age. Among employees younger than 59½, age is negatively related to leaving match money on the table, while the reverse is true for employees older than 59½—a pattern consistent with Figure 1.

In Table 7, we replace the firm fixed effects with three variables associated with the 401(k) plan rules: the rate at which the first dollar of employee contributions to the plan is matched, the maximum possible match the employee can receive as a percent of salary, and the employee’s vesting percentage as of January 1, 1999. As expected, once vesting percentage is controlled for, the probability of having an arbitrage loss and the size of arbitrage losses are decreasing in tenure. The coefficients on the other employee characteristics remain qualitatively similar to those in the firm fixed effects regressions, except that marital status loses significance in predicting the presence of an arbitrage loss.

Table 7.

Predictors of arbitrage losses or foregone employer matching contributions in 1998, including 401(k) plan rule controls

| Employees older than 59½ |

Employees younger than 59½ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has arbitrage losses |

Contributes < match threshold |

Arbitrage losses (% of salary) |

Matching contributions foregone (% of salary) |

Contributes < match threshold |

Matching contributions foregone (% of salary) |

||

| Male | 0.064** | 0.058** | 0.582** | 0.519** | Male | 0.027** | 0.180** |

| (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.096) | (0.093) | (0.003) | (0.015) | ||

| Married | −0.029 | −0.044** | −0.320** | −0.309** | Married | −0.054** | −0.309** |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.090) | (0.087) | (0.003) | (0.014) | ||

| Log(Tenure) | −0.067** | −0.063** | −0.198** | −0.233** | Log(Tenure) | −0.046** | −0.105** |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.067) | (0.065) | (0.003) | (0.014) | ||

| Log(Salary) | −0.272** | −0.298** | −1.584** | −1.616** | Log(Salary) | −0.290** | −1.507** |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.088) | (0.084) | (0.003) | (0.015) | ||

| Age = 60 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.174 | 0.143 | Age 20–29 | −0.164** | −0.058 |

| (0.025) | (0.026) | (0.146) | (0.139) | (0.035) | (0.124) | ||

| Age = 61 | 0.039 | 0.037 | 0.321* | 0.302* | Age 30–39 | −0.177** | −0.072 |

| (0.027) | (0.028) | (0.155) | (0.148) | (0.036) | (0.124) | ||

| Age = 62 | 0.042 | 0.054 | 0.398* | 0.344* | Age 40–49 | −0.177** | −0.087 |

| (0.030) | (0.031) | (0.172) | (0.164) | (0.037) | (0.124) | ||

| Age = 63 | 0.020 | 0.015 | 0.146 | 0.049 | Age 50–59½ | −0.251** | −0.477** |

| (0.033) | (0.033) | (0.186) | (0.178) | (0.033) | (0.125) | ||

| Age = 64 | 0.122** | 0.094* | 0.561** | 0.517** | |||

| (0.039) | (0.039) | (0.208) | (0.201) | ||||

| Age ≥ 65 | 0.110** | 0.128** | 0.752** | 0.726** | |||

| (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.157) | (0.152) | ||||

| First dollar | 0.127 | 0.143 | −1.011* | 0.021 | First dollar | 0.533** | 1.896** |

| match rate | (0.090) | (0.092) | (0.516) | (0.493) | match rate | (0.013) | (0.065) |

| Maximum | −6.685** | −4.948** | 16.082 | −6.530 | Maximum | −9.741** | −19.483** |

| match % | (1.666) | (1.678) | (9.774) | (9.024) | match % | (0.254) | (1.250) |

| % vested | 0.544** | −0.112** | 0.292 | −0.547** | % vested | −0.132** | −0.923** |

| (0.041) | (0.039) | (0.306) | (0.195) | (0.007) | (0.031) | ||

| Sample size | 5,043 | 5,043 | 4,395 | 5,043 | Sample size | 158,894 | 158,894 |

Note: This table presents the results of regressions with one of four dependent variables: (1) a binary indicator for whether an employee had arbitrage losses, (2) a binary indicator for whether an employee contributed less than the match threshold, (3) arbitrage losses as a percent of salary, and (4) matching contributions foregone as a percent of salary. Regressions with binary dependent variables are probits, and regressions with continuous dependent variables are tobits censored below at 0% and above at the maximum possible value for each individual. The sample is restricted to employees eligible for their 401(k) match and whose 1998 salary is more than that of a full-time minimum wage worker. The sample for the arbitrage loss as a percent of pay regression is further restricted to exclude participants who contribute below the match threshold but whom we do not categorize as having arbitrage losses due to their after-tax balances or vesting status. The ages used to sort employees into subsamples are computed as of January 1, 1998. The explanatory variables are a male dummy, a married dummy, the participant’s age on January 1, 1998, the log of the number of years since the participant’s original hire date as of December 31, 1998, the log of the participant’s salary in 1998, the rate at which the first dollar contributed is matched, the maximum possible match the employee can receive as a percent of salary, and the employee’s vesting percentage as of January 1, 1999. For the last three variables, 1% is coded as 0.01. For the probit regressions, the point estimates are marginal effects evaluated at the means of the explanatory variables; the marginal effect reported for dummy variables is the effect of changing the variable from 0 to 1. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Significant at the 5% level.

Significant at the 1% level.

The coefficients on the plan rule variables themselves indicate that among over-59½ year olds, a higher first-dollar match rate is associated with lower arbitrage loss magnitudes, and a higher maximum possible match is associated with a lower probability of having an arbitrage loss or contributing less than the match threshold. Vesting percentages are positively correlated with the probability of having an arbitrage loss, but negatively correlated with the probability of contributing less than the match threshold and the amount of matching contributions foregone. Among younger employees, a higher first-dollar match rate is associated with a higher likelihood of contributing less than the match threshold and a higher amount of matching contributions foregone. But a higher maximum possible match is negatively associated with these two outcomes. The plan rule coefficients must be interpreted with caution. The correlations may not be causal, because the firms could be adjusting their plan rules in response to their employees’ savings propensities, and employees could be self-sorting into firms based on the fit between their savings propensities and the firms’ 401(k) plan rules.

VI. Field Experiment

To gain further insight into why employees are contributing sub-optimally to their 401(k), and to see if providing information about the employer match and withdrawal rules would increase 401(k) contributions, we conducted a field experiment at Company F in partnership with Hewitt Associates. On August 3 and 4, 2004, we mailed treatment and control surveys to 889 Company F employees over the age of 59½. The survey sample includes all 689 employees at Company F who were contributing less than the match threshold as of May 2004, as well as 200 randomly selected employees contributing at or above the match threshold.

We randomly divided our sample of 689 employees contributing below the match threshold into two equal-sized subgroups: a control group and a treatment group. The control group survey included questions about the employee’s satisfaction with and knowledge about the 401(k) plan, general financial literacy, and savings preferences.24 The control survey was also sent to all of the 200 employees contributing at or above the match threshold. The treatment group survey was identical to the control survey, except that it included five additional questions designed to educate the respondent, which we describe later. We estimate that it would take employees about 15 minutes to complete the control survey and 20 minutes to complete the treatment survey.

To 200 employees in each of the three groups (below the match threshold control group, above the match threshold control group, below the match threshold treatment group), we promised a $50 American Express Gift Cheque if they responded no later than August 27, 2004. Even in non-401(k) domains, employees below the match threshold appear less willing or able to collect cheap money than employees at or above the match threshold. The survey response rate among employees at or above the match threshold was much higher (52%) than among employees below the threshold who were offered $50 (24%), even though the former group’s median income is higher than the latter’s.25 The average respondent contributing at least up to the match threshold took 15.1 days to mail the survey back to us, while the average respondent below the threshold who received $50 took 17.6 days, suggesting that employees below the threshold are more prone to procrastinate.

Due to the low overall response rate, we only briefly summarize the key findings from the survey. A more detailed discussion is in Choi, Laibson, and Madrian (2005).

Consistent with the difference in response delays, fewer respondents at or above the match threshold (11%) than respondents under the threshold (16%) report themselves to often or almost always leave things to the last minute. We find little evidence that direct transactions costs are prohibitive. The average respondent who was not participating in the 401(k) plan believed that it would take 1.7 hours to join the plan, 1.3 hours to change his plan contribution rate for the first time, and 1.5 hours to change his plan asset allocation for the first time. The average respondent who had actually engaged in these transactions reported even lower averages of 1.4, 0.6, and 0.6 hours, respectively. Among employees who claimed that they did not ever plan on enrolling in the 401(k), none cited the time it takes to enroll as a reason for non-participation. There is a striking lack of financial literacy among those below the match threshold. Fifty-three percent incorrectly believe their own employer’s stock to be less risky than a large U.S. stock mutual fund, a belief shared by only 26% of employees contributing at or above the match threshold.26 Employees saving below the match threshold are also not particularly knowledgeable about their 401(k) plan features, as only 21% were able to correctly state their employer match rate, and only 27% were able to correctly state the match threshold. In contrast, employees at or above the threshold were able to correctly state these figures 41% and 59% of the time, respectively.

The main purpose of the survey was to see whether employees under the match threshold would increase their 401(k) contributions if the benefits of the employer match and the penalty-free withdrawal rules were explained to them. To accomplish this, the survey sent to the treatment group included an additional five questions at the end. The first three asked when the respondent became aware of the following facts: (1) the company matches the first 6% of salary contributed to the 401(k), (2) transactions in the 401(k) could be made via the Internet, a touch-tone phone system, or by speaking to a benefits center representative on the phone, and (3) penalty-free withdrawals from the 401(k) were available for any reason for participants over age 59½. The fourth question asked respondents to calculate the amount of employer match money they would lose each year if they did not contribute at all to the 401(k). Respondents received a matrix of match amounts corresponding to various match rates and salaries to aid this calculation. The median respondent calculated that he would lose $1,200 each year if he contributed nothing. The final question asked if the employee was interested in raising his contribution rate to 6% in light of the losses just calculated.

Table 8 presents the average 401(k) contribution rates—adding together the before-tax and after-tax rates—on August 1, 2004 (immediately prior to the survey mailing) and November 1, 2004 (approximately two months after the survey response deadline) for employees who were under the match threshold in May 2004 (when the survey mailing list was finalized) and still with the company on November 1, 2004. The average contribution rates of the control and treatment groups increase over this period, but by a very small amount (0.07% and 0.17% of pay for the control and treatment groups, respectively). The intent-to-treat effect, which is the difference in the average contribution rate change between the two groups, is only an increase of 0.10% of pay, which is statistically insignificant.27 Using receipt of the treatment survey as an instrument for reading and returning the treatment survey, we estimate a larger treatment effect—a 0.67 percentage point increase in the contribution rate—but this effect remains statistically insignificant, making it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the intervention’s efficacy among those it successfully reached.

Table 8.

Field experiment results, company F

| Pre-survey (8/1/2004) |

Post-survey (11/1/2004) |

Change (Post – Pre) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group (N = 315) |

1.74% (0.15) |

1.91% (0.17) |

0.17% (0.08) |

| Control group (N = 320) |

2.09% (0.16) |

2.17% (0.16) |

0.07% (0.05) |

| Difference (Treatment – Control) |

−0.35% (0.22) |

−0.26% (0.23) |

0.10% (0.09) |

| Instrumental variable estimate of treatment effect |

0.67% (0.63) |

Note: This table shows the average 401(k) contribution rates as a percent of pay on August 1, 2004 (pre-survey) and November 1, 2004 (post-survey) for the treatment and control groups, as well as differences across groups and across time. Standard errors are in parentheses. The sample is Company F employees contributing below the match threshold in May 2004. The control group received a mailed survey about their 401(k) plan. The treatment group received the control survey plus additional questions that highlighted the losses from not contributing up to the match threshold. The last row gives the instrumental variable estimate of the treatment effect, where assignment to the treatment group is an instrument for completing the survey.

VII. Conclusion

Despite the presence of employer matching contributions in 401(k) plans, a substantial fraction of employees fail to contribute up to their employer’s match threshold. For some employees, it is possible to rationalize their willingness to leave employer 401(k) matching contributions on the table by appealing to factors such as liquidity constraints, early withdrawal penalties, and lack of vesting of the match. In this paper, we examine the 401(k) contribution choices of a group of employees for whom these explanations do not apply. These employees are older than 59½, receive employer matching contributions, are vested, and can withdraw from their 401(k) for any reason without penalty. For these employees, contributing below the match threshold violates the no-arbitrage condition for their portfolio. Nevertheless, in the average firm in our sample, 36% of match-eligible employees over 59½ forego free lunches by contributing under the threshold, losing arbitrage profits that are on average 1.6% of their annual pay, or $507. The dollar amount of the arbitrage losses over a longer time horizon are likely much larger. The widespread failure of the no-arbitrage condition in this context suggests that these employees suffer additional utility losses from imperfect optimization in other areas of their investing and saving.

Based on survey evidence coupled with cost-benefit analysis, we rule out direct transactions costs as the primary reason for the failure to fully exploit the employer match. Instead, we find evidence that employees contributing below the match threshold are more prone to procrastinate and are less financially literate than those at or above the match threshold. Providing information on the size and liquidity of the employer match raises 401(k) contribution rates, but the effect is not statistically distinguishable from zero.

Our results are cause for pessimism about the ability of monetary incentives alone to increase savings in the left tail of the savings distribution. Despite offering costly matching programs with strong marginal financial incentives, the firms studied here were unable to induce many of their older employees to contribute up to the match threshold. Although matching alone does not appear sufficient to significantly increase savings in the left tail, it may be more effective when combined with other interventions that account for employee passivity (Madrian and Shea, 2001; Benartzi and Thaler, 2004; Choi, Laibson, Madrian, and Metrick, 2002, 2004; Carroll et al., 2009; Beshears et al., 2010) or sharply reduce the complexity of the savings and investment decision (Beshears et al., 2006; Duflo, et al., 2006; Mitchell, Utkus, and Yang, 2006; Choi, Laibson, and Madrian, 2009).

Finally, the results in this paper speak more generally to the role of the no-arbitrage condition in economic equilibria. Among the population studied in this paper, unexploited arbitrage opportunities are commonly observed, despite the fact that the potential gains are large and the necessary strategy to capitalize on these gains is simple. Our evidence suggests that in non-competitive domains like retirement saving where the failure to maximize cannot be exploited by others, arbitrage opportunities may persist in equilibrium.

Footnotes

This paper originally circulated under the title, “$100 Bills on the Sidewalk: Suboptimal Saving in 401(k) Plans.” We thank Hewitt Associates for providing the data and for their help in designing, conducting, and processing the survey analyzed in this paper. We are particularly grateful to Lori Lucas, Yan Xu, and Mary Ann Armatys, some of our many current and former contacts at Hewitt Associates, for their feedback on this project. Outside of Hewitt, we have benefited from the comments of Erik Hurst, Ebi Poweigha, and seminar participants at Berkeley, Harvard, and the NBER. We are indebted to John Beshears, Carlos Caro, Yeguang Chi, Keith Ericson, Holly Ming, Laura Serban, and Eric Zwick for their excellent research assistance. Choi acknowledges financial support from a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and the Mustard Seed Foundation. Choi, Laibson, and Madrian acknowledge individual and collective financial support from the National Institute on Aging (grants R01-AG021650 and T32-AG00186). The survey was supported by the U.S. Social Security Administration through grant #10-P-98363-1 to the National Bureau of Economic Research as part of the SSA Retirement Research Consortium. The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of NIA, SSA, any other agency of the Federal Government, or the NBER. Laibson also acknowledges financial support from the Sloan Foundation and the National Science Foundation (grant HSD-0527516).

Skinner (2007) surveys the debate on U.S. savings adequacy. Studies that conclude there is a significant under-saving problem include Bernheim (1997), Mitchell and Moore (1998), Warshawsky and Ameriks (2000), and Munnell, Webb, and Delorme (2006). Studies that argue under-saving is uncommon include Hubbard, Skinner, and Zeldes (1995), Engen, Gale, and Uccello (1999), and Scholz, Seshadri, and Khitatrakun (2006). Our results are not necessarily inconsistent with this latter group of papers; it may be the case that the majority of households are acting optimally, but a substantial minority is making serious mistakes.

The recommendation to hold a diversified portfolio is foundational to modern portfolio theory. However, theoretical and empirical defenses of concentrated portfolio holding include DeMarzo, Kaniel, and Kremer (2004), Ivković and Weisbenner (2005), Massa and Simonov (2006), Van Nieuwerburgh and Veldkamp (2006, 2010), and Ivković, Sialm, and Weisbenner (2008).

In the short run, the employee’s gain from increased matches is the employer’s loss. Nevertheless, employers have been rapidly adopting measures such as automatic enrollment in order to boost their 401(k) participation rates, despite the increased matching expenditures required. This is in part driven by a desire to satisfy IRS non-discrimination rules. In the long run, it is not clear that higher matching expenditures will raise compensation costs. If the firm can reduce wage growth to offset matching expenditures, then the tax advantages of compensating workers through the pension plan could actually reduce compensation costs.

Venti and Wise (1992) make a related point, noting that many individuals older than 59½ do not have IRAs, even though IRA balances are tax-advantaged and can be withdrawn without penalty by these households. They do not, however, calculate the extent of any losses associated with IRA non-participation.

We also mailed surveys to 4,000 employees below the age of 59½. Results from those respondents are available on request.

This stands in contrast to vesting practices for employee stock options, where each option grant comes with its own vesting schedule tied to when the grant was made, so that an employee may simultaneously have different option grants that are fully vested, partially vested, and not vested at all.

The annual salary cutoff we use is $5.15/hour × 35 hours/week × 50 weeks/year = $9,012.50.

Direct withdrawals from the 401(k) are subject to a mandatory 20% withholding that is credited towards the employee’s overall tax liability. This withholding can be bypassed, if desired, by rolling over the withdrawal into one’s IRA, and then withdrawing from the IRA.

This calculation takes into account two relevant IRS limits on 401(k) contributions which apply to individuals (rather than households). First, IRS section 402(g)(3) sets a maximum dollar limit on an employee’s before-tax contributions, which was $10,000 per year in 1998. Second, IRS section 415(b)(1)(A) prohibits employee 401(k) contributions out of annual compensation above a certain amount, which was $160,000 in 1998. (Both thresholds have increased in subsequent years.) In a plan that matches 100% of contributions up to 5% of salary, an employee who earned $200,000 in 1998 could only receive a maximum of $8,000 that year in matching contributions ($160,000 × 0.05). Because the match threshold for employees in our sample does not exceed 6%, the $10,000 contribution limit does not in practice constrain any employees from receiving the full employer match available under their plan rules once the $160,000 compensation limit is accounted for.