Abstract

Activated CD4 T cells are associated with protective immunity and autoimmunity. The manner in which the inflammatory potential of T cells and resultant autoimmunity is restrained is poorly understood. In this article, we demonstrate that T cell factor-1 (TCF1) negatively regulates the expression of IL-17 and related cytokines in activated CD4 T cells. We show that TCF1 does not affect cytokine signals and expression of transcription factors that have been shown to regulate Th17 differentiation. Instead, TCF1 regulates IL-17 expression, in part, by binding to the regulatory regions of the Il17 gene. Moreover, TCF1-deficient Th17 CD4 T cells express higher levels of IL-7Rα, which potentially promotes their survival and expansion in vivo. Accordingly, TCF1-deficient mice are hyperresponsive to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Thus, TCF1, a constitutively expressed T cell-specific transcription factor, is a critical negative regulator of the inflammatory potential of TCR-activated T cells and autoimmunity.

Activated CD4 T cells differentiate into distinguishable Th cell subsets to mount effective and diverse immune responses against different pathogens. CD4 T cells differentiate into Th subsets in response to cytokines, produced by cells of the innate immune system, as well as activated T cells, in the pathogenic environment. These subsets have specialized characteristics defined by the cytokines that they produce. The recently defined Th17 cells develop in response to TGF-β and IL-6 or IL-21 and produce IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, and IL-22 to clear certain classes of extracellular pathogens (1–8). In addition to TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-21, cytokines, such as IL-23 and IL-7, promote survival and expansion of Th17 cells. Conversely, IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-27 inhibit Th17 cell differentiation (1, 2, 9, 10). At the molecular level, transcription factors STAT3, RORγt, RORα, IRF-4, Runx1, BATF, and IκBζ promote Th17 lineage differentiation (1, 2, 11–13), whereas Foxp3, Gfi-1, and Ets-1 inhibit this process by inhibiting the activity of RORγt or by directly repressing Il17 gene transcription (14–16). Thus, a network of cytokines and NFs positively and negatively regulate Th17 differentiation. In addition to the protective function, Th17 cells have been causally associated with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), experimental colitis in mice, and inflammatory bowel disease in humans and mice (17–20). Evidence has shown that cytokines produced by Th17 cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of EAE (1, 2, 21, 22). However, evidence also exists to suggest that they may not be the major mediators of autoimmune inflammation (23). Thus, further characterization of the pathogenic CD4 T cells has important implications for combating autoimmune diseases.

The T cell factor (TCF) family of transcription factors activates gene expression in conjunction with β-catenin, and it represses gene expression with corepressors of the Groucho (Grg/TLE) family of proteins (24–26). The vertebrate TCF family consists of four proteins: TCF1, lymphocyte enhancer binding factor, TCF3, and TCF4 (27). TCF1 is specifically expressed in T cells in adult mice and has been shown to regulate T cell development (28, 29). However, the role of TCF1 in mature T cell function has remained less well characterized. We only recently showed that TCF1 induces GATA3 expression to promote Th2 fate in CD4 T cells (30). The mechanism by which TCF1 controls gene expression in mammalian cells remains unclear. In particular, very few mammalian genes that are repressed by TCF1 have been identified, and the mechanism by which TCF1 mediates repression is not well understood (26, 31).

In this report, we demonstrate that TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells produce higher levels of several Th17 cytokines. Taken together with the observation that TCF1 directly binds to the Il17 gene, these data are consistent with the view that Th17 cytokines may be directly negatively regulated by TCF1. This notion is also consistent with the observation that TCF1 deficiency does not affect cytokine signals or transcription factors that regulate Th17 differentiation. In addition, TCF1-deficient Th17 cells express higher levels of IL-7Rα, which was shown to enhance the survival of Th17 cells in vivo (10). Accordingly, TCF1-deficient mice are hyperresponsive to EAE. In light of these data, we propose that TCF1, a constitutively expressed T cell-specific transcription factor, protects mice from autoimmune responses by repressing inflammatory cytokine production by, and regulating IL-7Rα expression on, Th17 cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals

TCF1-deficient mice (32) were provided by H. Clevers (Hubrecht Institute, Utrecht, The Netherlands). Generation of transgenic mice that overexpress β-catenin (β-CAT–Tg) and ICAT mice were described previously (33, 34). Age-matched littermate controls or C57BL/6 mice were used in all experiments. All mice were bred and maintained in an animal facility at the National Institute on Aging according to National Institutes of Health regulations and were in compliance with the guidelines of the National Institute on Aging animal resources facility, which operates under the regulatory requirements of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Abs and flow cytometry

Cells were harvested, stained, and analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). Dead cells were excluded by forward light scatter or forward light scatter plus propidium iodide. All data were acquired and presented on log scale. Abs with the following specificities from BD Pharmingen were used for staining: allophycocyanin-CD4 (GK1.5), PerCP-Cy5.5-CD8α (53–6.7), FITC-CD69 (H1.2F3), PE-CD25 (PC61), PE-CD44 (IM7), FITC-CD62L (MEL-14), and PE-phosphoSTAT3 (4-P/STAT3). Purified anti-CD3 (145-2C11), anti-CD28 (37.51), anti–IL-4 (11B11), and anti–IFN-γ (XMG1.2) were from BD Pharmingen. PE–IL-17A (17B7), PE–IL-6Rα (D7715A7), PE–IL-21R (4A9), PE–IL-2 (JES6-5H4), and FITC–IFN-γ (XMG1.2) Abs were purchased from eBioscience.

In vitro CD4 T cell differentiation

Naive CD62L+CD4+ T cells were purified from spleen and lymph nodes by negative selection and then positive selection using a mouse CD4+CD62L+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi). The resulting cells were highly enriched for CD44loCD62Lhi naive cells. CD4 T cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (145-2C11) plus anti-CD28 (37.51). On day 3 of culture, cells were diluted with medium containing IL-2 (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems). For Th17-promoting culture, TGF-β (5 ng/ml), IL-6 (10 ng/ml) (both from R&D Systems), anti–IFN-γ (10 μg/ml), and anti–IL-4 (10 μg/ml) were added in stimulation culture. On indicated days, cells were restimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 4 h, with the addition of GolgiStop in the last 2 h. Cells were then harvested and stained for intracellular cytokines.

Quantitative (real-time) RT-PCR

Total mRNA was reversed transcribed using poly(dT) and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The cDNA was subjected to real-time RT-PCR amplification (Applied Biosystems) for 40 cycles with annealing and extension temperature at 60°C. Primer sequences are provided in Supplemental Table I.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

CD4 T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 for 1 d, and chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed using a kit from Upstate Cell Signaling, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Chromatin was precipitated with a rabbit anti-TCF1 Ab (kindly provided by Dr. Marian Waterman) or normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz), followed by salmon sperm-coated protein A-agarose (Upstate Cell Signaling). The precipitates were subjected to real-time PCR using primers specifically designed to detect TCF1-binding sites (Supplemental Table I). DNA recovered from anti-TCF1 and IgG immunoprecipitates is expressed relative to input DNA using the following formula: immunoprecipitation relative to input = (DNA in immunoprecipitate)/(DNA in total input) × 4000.

Induction of EAE

Mice were injected s.c. with 200 μg myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)35–55 peptide (AnaSpec) emulsified in CFA (Difco) and injected i.p. with 400 ng pertussis toxin (Sigma). Two days later, mice were injected with pertussis toxin again. At different times after the immunization, clinical scores were examined using the following criteria: 0, normal; 1, tail paralysis; 2, partial paralysis of hind limbs; 3, complete paralysis of hind limbs; 4, complete paralysis of hind and fore limbs (moribund); and 5, death. On day 21 after MOG injection, lymph node and splenic cells from mice were restimulated in vitro with MOG (50 ng/ml) for 1 d, and GolgiStop was added to the culture for the last 5 h. The cells were then transiently restimulated with PMA plus ionomycin and stained for intracellular IL-17.

Results

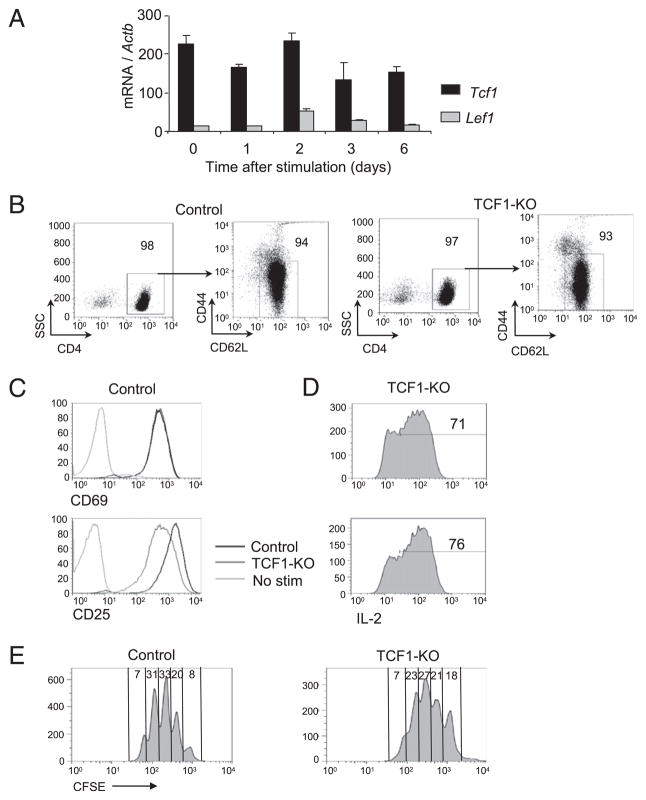

TCF1 deficiency does not affect TCR-mediated activation of CD4 T cells

Transcription factors TCF1, and, at a much lower level, lymphocyte enhancer binding factor are constitutively expressed in CD4 T cells and remain largely unaffected by TCR stimulation (Fig. 1A). In TCF1-deficient mice, peripheral CD4 T cells contain a relatively smaller percentage of naive cells and a higher frequency of effector/memory cells. We used standard purification methods to enrich for naive CD4 T cells. The resulting purity of CD4 T cells from control and TCF1-deficient mice was 98 and 97%, respectively. Moreover, the great majority of these cells (94 and 93%) were of CD62LhiCD44lo naive phenotype (Fig. 1B). TCF1-deficient naive CD4 T cells respond to TCR signals by expressing activation markers, producing IL-2, and proliferating at comparable level as control CD4 T cells (Fig. 1C–E). However, survival of TCR-activated CD4 T cells, with no added cytokines, is compromised over 3 d of activation (data not shown). These data demonstrated that TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells are activated by TCR signal, produce IL-2, and proliferate in a manner comparable to wild type CD4 T cells.

FIGURE 1.

Naive-enriched TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells show normal activation to TCR stimulation. A, Real-time PCR analysis of Tcf1 and Lef1 mRNA in cells stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for various times, presented relative to Actb. Data are pooled from two independent experiments. B, Flow cytometry of naive-enriched control and TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells used as the starting populations in most of the experiments. The purity and the high percentage of naive CD44loCD62L+ population in CD4 T cells are shown. Data are representative of at least six independent analyses. C, Flow cytometry of CD69 and CD25 expression on control and TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 1 d. Data are representative of four independent analyses. D, IL-2 production by CD4 T cells stimulated as in C and followed by intracellular IL-2 staining. Numbers represent the percentage of IL-2+ cells. Data are representative of four independent analyses. E, Dilution of CFSE by control or TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 Abs for 3 d. Numbers represent the percentage of cells in each cell division. Data are representative of eight independent analyses.

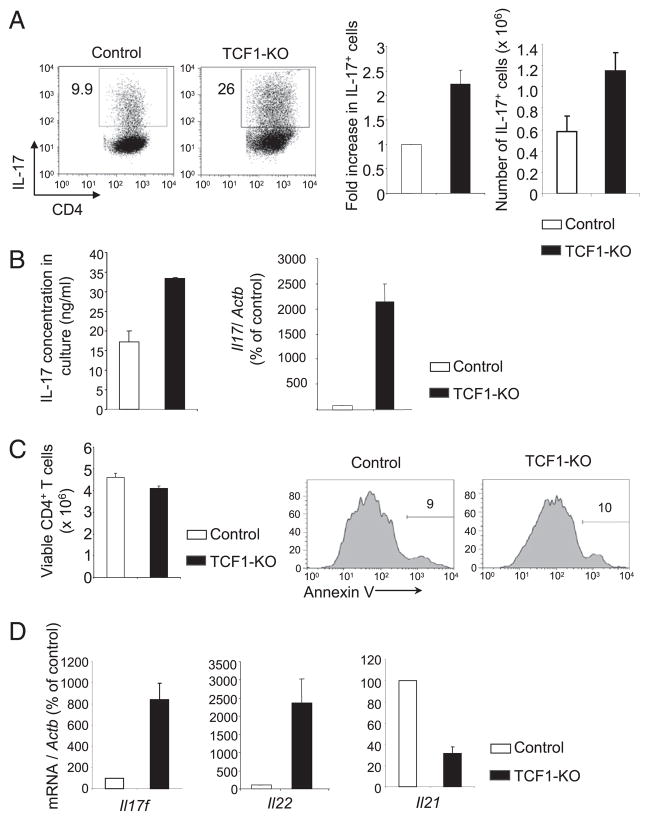

TCF1 negatively regulates IL-17 production in CD4 T cells

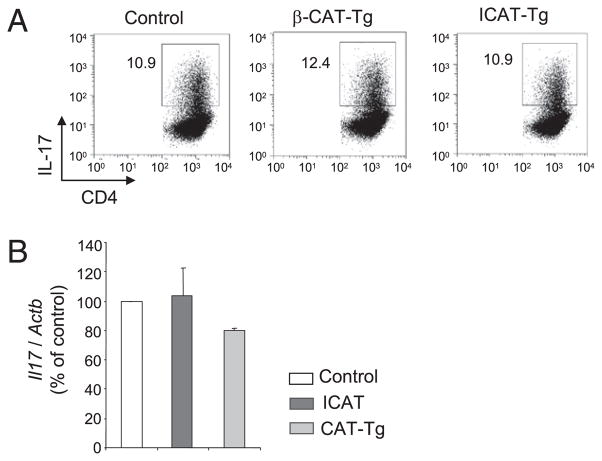

To determine whether TCF1 regulates the differentiation of IL-17–producing Th17 cells, we activated naive TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells in Th17-promoting conditions with added TGF-β and IL-6. After 3 d of culture, ~3-fold more TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells produced IL-17 compared with control CD4 T cells, both in frequency and in absolute number (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the amount of IL-17 secreted into the culture supernatant of TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells was higher, as determined by ELISA (Fig. 2B). Consistent with increased IL-17 production, we noted that TCF1-deficient Th17 CD4 T cells expressed a greater amount of Il17 mRNA compared with control CD4 T cells (Fig. 2B). This was not due to selective depletion of non–IL-17–producing TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells, because we recovered comparable numbers of viable CD4 T cells from TCF1-deficient and control cultures (Fig. 2C). In addition, Annexin V staining showed that the proportion of apoptotic cells was also comparable in cultures of TCF1-deficient and control CD4 T cells (Fig. 2C). Among other cytokines produced by Th17 cells, the relative abundance of Il17f and Il22 mRNA, but not Il21 mRNA, was increased in TCF1-deficient cells compared with control Th17 cells (Fig. 2D). Finally, to understand whether IL-17 production was dependent on TCF1 and β-catenin, we used CD4 T cells from β-CAT–Tg (33) and transgenic mice that express ICAT, a specific inhibitor of β-catenin and TCF1 interactions (34). We found that IL-17 production was not affected by overexpression of β-catenin or disruption of TCF1 and β-catenin interactions (Fig. 3). These data demonstrated that TCF1 negatively regulates IL-17 production in a β-catenin–independent manner. We concluded that TCF1 negatively regulates production of Th17-derived cytokines.

FIGURE 2.

TCF1 negatively regulates the generation of IL-17–producing CD4 T cells. A, Flow cytometry of control and TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells stimulated for 3 d with plate-bound anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 in the presence of TGF-β and IL-6 together with anti–IFN-γ plus anti–IL-4 Abs. Bar graphs show fold increase in the percentage (left) and absolute number (right) of IL-17+ CD4 T cells. Data are from eight independent samples. B, ELISA analysis of IL-17 concentration in the culture supernatant from the cells stimulated as in A. Real-time PCR analysis of Il17 mRNA in cells stimulated as in A, presented relative to Actb and relative to that of activated control CD4 T cells, set as 100%. C, Number of viable control and TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells, as assessed by trypan blue exclusion (left panel). Data are from six independent analyses. Flow cytometry of Annexin V staining in control and TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells stimulated as in A. Numbers represent the percentage of Annexin V+ cells (middle and right panels). Data are from two independent analyses. D, Real-time PCR analysis of cytokine mRNA in cells stimulated as in A, presented relative to Actb and to that of TCR-activated control CD4 T cells, set at 100%. Data are from eight independent samples.

FIGURE 3.

TCF1 represses IL-17 production independently of β-cat-enin. A, Flow cytometry of IL-17 expression in β-CAT–Tg and ICAT CD4 T cells stimulated for 3 d with plate-bound anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 under Th17-promoting conditions. Numbers in the plots indicate the percentage of IL-17+ CD4 T cells. B, Real-time PCR analysis of Il17 mRNA in cells stimulated as in A, presented relative to Actb and to that of activated control CD4 T cells, set as 100%.

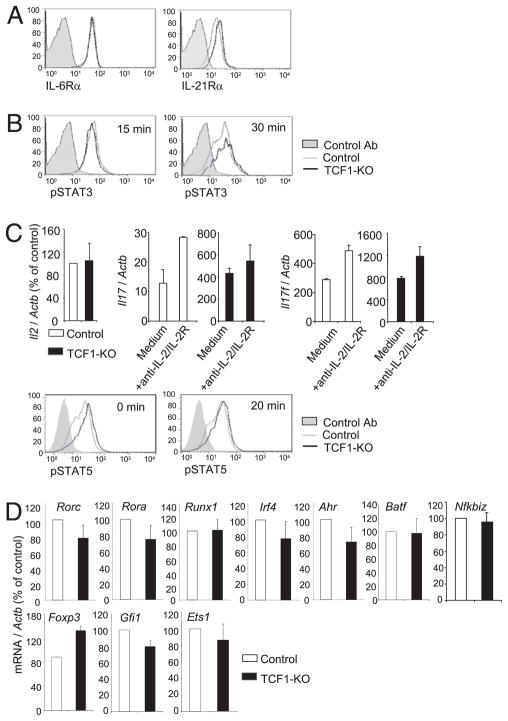

TCF1 deficiency does not affect known regulators of Th17 differentiation

The enhanced commitment of TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells to the Th17 fate could result from increased signaling by Th17-promoting cytokines IL-6 or IL-21 (4–8). We found that surface expression of IL-6Rα and IL-21Rα was comparable in TCF1-deficient and control cells (Fig. 4A). IL-6R signaling also was not affected by TCF1 deficiency, because we found no difference in the abundance of pSTAT3 in TCF1-deficient and control CD4 T cells at two different time points after IL-6 stimulation (Fig. 4B). In addition, suppressor of cytokine signaling-3, a negative regulator of IL-6 signaling and Th17 differentiation, was expressed comparably in control and TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells (data not shown). IL-2R signaling negatively regulates Th17 cells (35). TCR-activated TCF1-deficient and control CD4 T cells produce comparable amounts of IL-2 after stimulation for 1 d in Th17-promoting conditions (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, blockade of IL-2R signaling did not affect increased IL-17 expression by TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells, whereas the amount of IL-17 produced by control cells was increased (Fig. 4C). This may be explained by the observation that the response of TCF1-sufficient or -deficient CD4 T cells to IL-2 (produced by activated CD4 T cells themselves or exogenously added) was comparable, as judged by equivalent STAT5 phosphorylation (Fig. 4C). Together, these data showed that increased expression of Th17-specific cytokines in TCR-activated TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells was not caused by changes in IL-6R, IL-21R, or IL-2R expression or signaling.

FIGURE 4.

TCF1 does not affect known regulators of Th17 differentiation. A, Flow cytometry of surface IL-6Rα and IL-21Rα on freshly isolated naive CD4 T cells. Data are representative of six independent analyses. B, Freshly isolated CD4 T cells were transiently stimulated with IL-6 for 15 or 30 min and then assayed for intracellular pSTAT3. Data are representative of six independent analyses. C, Il2 mRNA in CD4 T cells stimulated under Th17-promoting conditions for 1 d (upper left panel). Il17 and Il17f mRNA in CD4+ T cells stimulated for 1 d under Th17-promoting conditions, in the presence or absence of anti–IL-2 plus anti-IL-2Rα Abs. Data are from two independent analyses (upper right panel). Intracellular pSTAT5 levels in CD4 T cells stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 1 d and then with IL-2 for 0 or 20 min. Data are representative of three independent analyses (lower panels). D, mRNA for Th17-regulating transcription factors in CD4 T cells stimulated under Th17-promoting conditions for 1 d. Data are from six independent samples.

Alternately, increased frequency of Th17 cells could result from increased expression of Th17-promoting transcription factors or decreased expression of Th17-inhibiting transcription factors. We found that the abundance of mRNA for genes that encode RORγt, RORα, RUNX1, IRF-4, aryl hydrocarbon receptor, BATF, and IκBζ, all of which promote Th17 fate, and Foxp3, Gfi-1 and Ets-1, known to inhibit Th17 fate, was comparable in TCF1-deficient and control CD4 T cells after 1 d of culture in Th17-promoting conditions (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these results demonstrated that TCF1 does not affect known regulators of Th17 cells and suggest that TCF1 might directly regulate the transcription of Th17-associated cytokine genes.

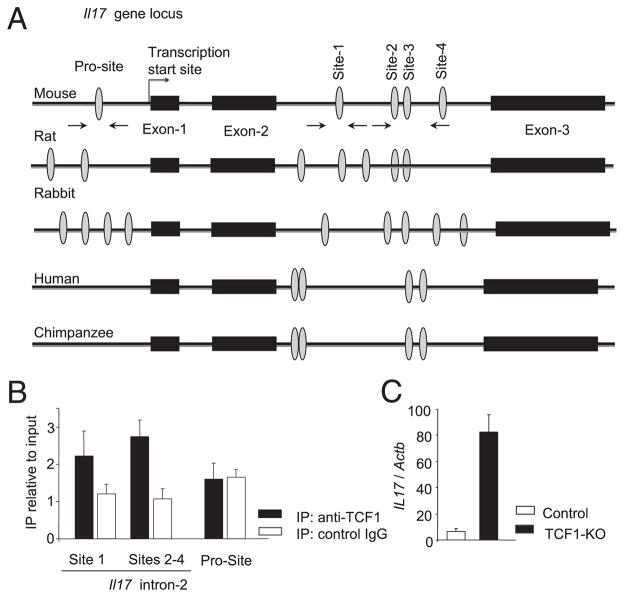

TCF1 binds to its cognate sites in the Il17 gene

The data shown above, taken with the greater abundance of IL-17 mRNA in TCF1-deficient Th17 cells compared with control cells, strongly suggested that TCF1 directly regulates Il17 gene expression. To address this issue, we searched for and identified TCF1-binding sites in the promoter region and in the second intron of the Il17 gene (Fig. 5A). Similar groups of TCF1-binding sites were found in the promoter region and the second intron of the Il17 gene in other species. Importantly, the TCF1-binding sites and their flanking sequences in the intron, but not the binding sites in the promoter of mouse Il17 gene, were conserved between mouse and rat (Fig. 5A). We designed primers to determine binding of TCF1 to these sequences in a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (Supplemental Table I). Using these primers, we determined that TCF1 bound to TCF1-binding sites in the second intron of the Il17 gene, but not to the TCF1-binding site in the promoter region, in TCR-stimulated CD4 T cells (Fig. 5B). DNA lacking TCF1-binding sites was used as a negative control (data not shown). Taken together with the observation that TCR-stimulated TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells expressed higher levels of Il17 mRNA (Fig. 5C), these data are consistent with the notion that TCF1 directly represses expression of the Il17 gene in TCR-activated CD4 T cells. We propose that TCF1, a constitutively expressed transcription factor, functions to curtail IL-17 production in CD4 T cells.

FIGURE 5.

TCF1 binds to its cognate sites in the Il17 gene. A, Schematic representation of the Il17 gene and TCF1-binding sites (ovals) in the promoter and the second intron. Arrows indicate the sites that primers bind. A comparison of TCF1-binding sites in the promoter region and the second intron of the Il17 gene in several species. B, C57BL/6 CD4 T cells that were stimulated for 1 d under neutral conditions without added cytokines were subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation with anti-TCF1 Ab or nonspecific isotype-matched control Ab (IgG). DNA sequences from the Il17 promoter and second intron that contain TCF1-binding sites were amplified by PCR and are presented relative to input DNA. Data are from four independent analyses. C, mRNA for the Il17 gene in CD4 T cells stimulated under neutral conditions without added cytokines for 1 d, presented relative to Actb. Data are from three independent samples.

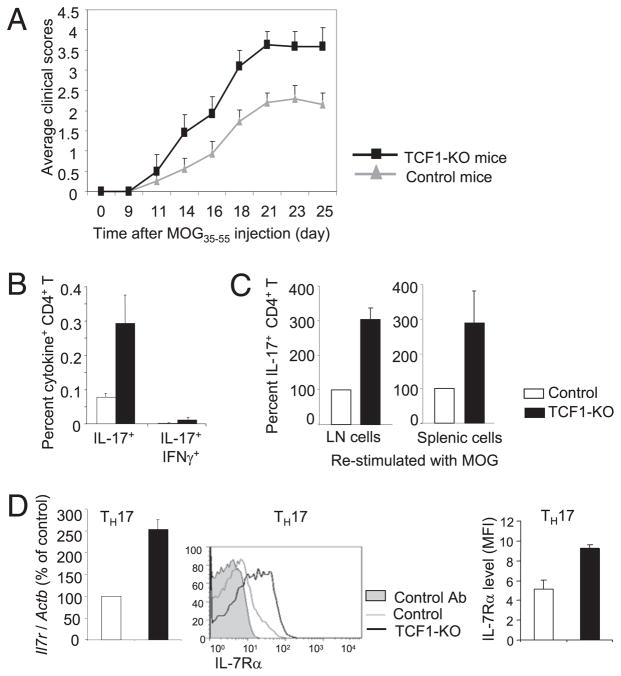

TCF1-deficient mice show increased susceptibility to EAE

Next, we tested whether increased production of IL-17 by activated TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells might render TCF1-deficient mice susceptible to EAE. To test this hypothesis, we injected control and TCF1-deficient mice with MOG35–55 peptide in CFA. We found that TCF1-deficient mice showed more severe symptoms as indicated by markedly higher clinical scores right from the start (Fig. 6A). Further analysis showed that a greater frequency and number of IL-17–producing CD4 T cells were found in MOG-injected TCF1-deficient mice compared with control mice (Fig. 6B, 6C). Because IFN-γ–producing cells have also been implicated in EAE, we tested whether TCF1 deficiency resulted in an increase in the frequency of the IL-17 and IFN-γ double-producing cells. We found that the frequency of double producers was much lower compared with IL-17–producing cells (Fig. 6B). Together, these data demonstrated that TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells develop more effectively into IL-17–producing cells and, consequently, TCF1-deficient mice show greater susceptibility to EAE development. We concluded that TCF1, which is constitutively expressed in CD4 T cells, is a negative regulator of IL-17 production and restrains pathogenesis of EAE. Accordingly, we propose that constitutive expression of TCF1 in CD4 T cells restrains the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-17 and IFN-γ, by activated CD4 T cells in wild type mice, which provides protection from autoimmune responses.

FIGURE 6.

TCF1 restrains EAE by inhibiting Th17 response and IL-7R expression on Th17 cells. A, Mice were injected with MOG35–55 in CFA, as well as pertussis toxin. Clinical scores were assessed at various times after injection. Data are from ≥21 mice for each group in three independent experiments. B, On day 21 after MOG injection, lymph node cells were analyzed for the frequency of IL-17 and IL-17 and IFN-γ double-producing CD4 T cells from control and TCF1-deficient mice. C, On day 21 after MOG injection, lymph node (LN) cells from mice were restimulated in vitro with MOG for 1 d and analyzed for intracellular IL-17. The graphs show the percentage of IL-17+ cells in CD4 T cell population, with that of control cells set at 100. D, On day 21 after MOG injection, lymph node cells were analyzed for expression of IL-7R on Th17 cells. mRNA for the Il7r gene relative to Actb (left panel) and IL-7R surface staining (middle and right panels) are shown. Shaded area, control Ab staining; grey line, control cells; black line, TCF1-KO cells.

Recently, IL-7Rα was shown to regulate survival and expansion of pathogenic Th17 effector cells in mouse EAE (10). Interestingly, variants in the IL-7Rα gene have also been associated with the risk for multiple sclerosis (MS) in humans (36). To determine whether TCF1 regulated IL-7R expression, we assayed its expression in control and TCF1-deficient Th17 cells. mRNA for Il7r, which encodes IL-7Rα protein, was more abundant in TCF1-deficient Th17 cells compared with control Th17 CD4 T cells (Fig. 6D). Accordingly, TCF1-deficient Th17 cells expressed greater levels of surface IL-7Rα compared with control Th17 cells (Fig. 6D). These data suggested that TCF1 negatively regulates expression of the Il7r gene in wild type Th17 cells to restrain autoimmune potential. Taken together with the recently characterized essential role of IL-7R signaling in the pathogenesis of EAE and its association with human MS (10), these data support a model in which greater IL-7Rα expression in TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells enhances survival and expansion of Th17 cells, thereby leading to an increase in the frequency of IL-17–producing CD4 T cells in TCF1-deficient mice.

Discussion

In this article, we demonstrated that TCR-activated TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells produced a greater abundance of Th17 cytokines compared with control CD4 T cells. Our data showed that TCF1 binds to regulatory regions of the Il17 gene and directly regulates Il17A and Il17F gene expression. Furthermore, we found that TCF1 regulates expression of IL-7Rα on Th17 cells, such that TCF1-deficient Th17 cells expressed higher levels of IL-7Rα on the cell surface, which enhanced their survival and expansion in vivo. These characteristics rendered TCF1-deficient mice hyperresponsive to EAE. Thus, we propose that TCF1, which is constitutively expressed in resting and TCR-activated CD4 T cells, plays an essential role in restraining production of a panel of inflammatory cytokines and expression of IL-7R, thereby protecting mice from spurious autoimmune responses.

Data from model organisms suggested that TCF1 transcription factors activate gene transcription in cooperation with β-catenin and negatively regulate gene expression with the Grg family of corepressors. However, transcriptional regulation by TCF1 is likely to be more complex, because TCFs were found to activate and repress transcription when bound to β-catenin (31). Regardless, in CD4 T cells, we recently demonstrated that TCF1 is constitutively expressed and, in cooperation with β-catenin, positively regulates GATA3 expression. We showed that TCF1 negatively regulates IFN-γ expression without affecting the expression of T-bet. Thus, a TCF1-dependent decrease in IFN-γ production and increased GATA3 expression promote Th2 differentiation (30). In this report, we demonstrated that TCF1 negatively regulated the expression of Th17-derived cytokines. Importantly, we found that TCF1 directly bound to several TCF1-binding sites in the regulatory region of the Il17 gene. Future studies will directly address whether this binding results in repression of Il17 gene transcription and whether Grg family repressors participate in this repression.

IL-7Rα expression regulates survival and homeostasis of CD4 T cells in vivo. Naive CD4 T cells express high levels of IL-7Rα, which is turned down on activated CD4 T cells and then re-expressed by Th17 and memory CD4 T cells (10, 37, 38). The mechanism by which IL-7Rα expression is regulated on CD4 T cells remains an important outstanding issue. Recent genome-wide association studies showed that polymorphisms at gene alleles encoding IL-7Rα are strongly associated with susceptibility to MS in humans (36, 39–41). Further studies showed that IL-7 is essential for the survival and expansion of pathogenic Th17 effector cells in mouse EAE (10). It was shown that Th17 cells, but not Th1 or regulatory T cells, are dependent on IL-7 for survival (10). Thus, we concluded that greater expression of IL-7Rα on TCF1-deficient Th17 cells, compared with control cells, contributes to increased clinical symptoms in TCF1-deficient mice.

Several transcription factors were shown to promote (1, 2, 11–13) or hinder (14–16) Th17 differentiation. Interestingly, expression of these remained unchanged in TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells. Expression of, and signaling by, the essential cytokine receptors were also comparable in TCF1-deficient and sufficient CD4 T cells. CD44 is an important target of β-catenin and TCF signaling in several cancers (42). We noted a slight decrease in CD44 expression on TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells, which is unlikely to play an important role because it promotes Th1 cell survival but does not have a similar role in the function of Th2 and Th17 cells (43). Response of CD4 T cells to IL-2 regulates Th17 differentiation through induction of pSTAT5 (35). We found that TCF1-deficient and control CD4 T cells produced similar levels of IL-2 and were comparably responsive to IL-2, as judged by STAT5 phosphorylation. Thus, TCF1 does not control IL-2 production or the response of CD4 T cells to IL-2. Together, these observations showed that Th17 differentiation factors remained unchanged in TCF1-deficient CD4 T cells and point to direct regulation of IL-17 by TCF1.

Failure to restrain cytokine production is the primary culprit in autoimmune responses. However, mechanisms that directly repress cytokine gene expression remain poorly defined. Transcription factors Blimp-1 and Ikaros were shown to inhibit IFN-γ expression by directly acting on genes encoding T-bet and IFN-γ (44, 45). Transcription factors Foxp3, Ets-1, and Gfi-1 were shown to negatively regulate Th17 differentiation. Among them, only Gfi-1 directly acts on Il17 genes. Gfi-1 is induced by IL-4 and IFN-γ and directly binds to Il17 genes and represses its expression in Th2 and Th1 cells (14). TGF-β downregulates Gfi-1, and this is necessary for optimal IL-17 production and Th17 cell differentiation. Unlike Gfi-1, TCF1 expression is not significantly downregulated by TGF-β and IL-6; thus, it is a constitutively present repressor of Il17 genes, which limits the production of IL-17 and IL-17F, even in an environment that favors Th17 differentiation. We suggest that this restraint might be important to elicit a measured response to the pathogen while preventing autoimmune responses. It will be important to fully characterize the mechanisms by which TCF1 inhibits IFN-γ and Th17-derived cytokines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health and in part by an appointment to the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education’s Research Associates Program at the National Institutes of Health.

We thank R. Wersto and team for cell sorting, the National Institute on Aging animal facility for maintaining animals, S. Luo and team for genotyping, K.E. Leeds for technical help, and H. Clevers for providing TCF1-deficient mice.

Abbreviations used in this article

- β-CAT–Tg

transgenic mice that overexpress β-catenin

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- TCF

T cell factor

Footnotes

The online version of the article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Awasthi A, V, Kuchroo K. Th17 cells: from precursors to players in inflammation and infection. Int Immunol. 2009;21:489–498. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez GJ, Nurieva RI, Yang XO, Dong C. Regulation and function of proinflammatory TH17 cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1143:188–211. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stockinger B, Veldhoen M. Differentiation and function of Th17 T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O’Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Wahl SM, Schoeb TR, Weaver CT. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korn T, Bettelli E, Gao W, Awasthi A, Jäger A, Strom TB, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2007;448:484–487. doi: 10.1038/nature05970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurieva R, Yang XO, Martinez G, Zhang Y, Panopoulos AD, Ma L, Schluns K, Tian Q, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Dong C. Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature. 2007;448:480–483. doi: 10.1038/nature05969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou L, I, Ivanov I, Spolski R, Min R, Shenderov K, Egawa T, Levy DE, Leonard WJ, Littman DR. IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:967–974. doi: 10.1038/ni1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ. Th17 cell differentiation: the long and winding road. Immunity. 2008;28:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Leung S, Wang C, Tan Z, Wang J, Guo TB, Fang L, Zhao Y, Wan B, Qin X, et al. Crucial role of interleukin-7 in T helper type 17 survival and expansion in autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2010;16:191–197. doi: 10.1038/nm.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou L, Littman DR. Transcriptional regulatory networks in Th17 cell differentiation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schraml BU, Hildner K, Ise W, Lee WL, Smith WA, Solomon B, Sahota G, Sim J, Mukasa R, Cemerski S, et al. The AP-1 transcription factor Batf controls T(H)17 differentiation. Nature. 2009;460:405–409. doi: 10.1038/nature08114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okamoto K, Iwai Y, Oh-Hora M, Yamamoto M, Morio T, Aoki K, Ohya K, Jetten AM, Akira S, Muta T, Takayanagi H. IkappaBzeta regulates T(H)17 development by cooperating with ROR nuclear receptors. Nature. 2010;464:1381–1385. doi: 10.1038/nature08922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu J, Davidson TS, Wei G, Jankovic D, Cui K, Schones DE, Guo L, Zhao K, Shevach EM, Paul WE. Down-regulation of Gfi-1 expression by TGF-beta is important for differentiation of Th17 and CD103+ inducible regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:329–341. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichiyama K, Hashimoto M, Sekiya T, Nakagawa R, Wakabayashi Y, Sugiyama Y, Komai K, Saba I, Möröy T, Yoshimura A. Gfi1 negatively regulates T(h)17 differentiation by inhibiting RORgammat activity. Int Immunol. 2009;21:881–889. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moisan J, Grenningloh R, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Ho IC. Ets-1 is a negative regulator of Th17 differentiation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2825–2835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC, Waldner H, Munder M, Bettelli E, Nicholson LB. T cell response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE): role of self and cross-reactive antigens in shaping, tuning, and regulating the autopathogenic T cell repertoire. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:101–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.081701.141316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouyang W, Kolls JK, Zheng Y. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity. 2008;28:454–467. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kastelein RA, Hunter CA, Cua DJ. Discovery and biology of IL-23 and IL-27: related but functionally distinct regulators of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:221–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouma G, Strober W. The immunological and genetic basis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:521–533. doi: 10.1038/nri1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, Nambu A, Ishigame H, Kakuta S, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:566–573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stromnes IM, Cerretti LM, Liggitt D, Harris RA, Goverman JM. Differential regulation of central nervous system autoimmunity by T(H)1 and T(H)17 cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nm1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovett-Racke AE, Yang Y, Racke MK. Th1 versus Th17: Are T cell cytokines relevant in multiple sclerosis? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brantjes H, Barker N, van Es J, Clevers H. TCF: Lady Justice casting the final verdict on the outcome of Wnt signalling. Biol Chem. 2002;383:255–261. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molenaar M, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Peterson-Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destrée O, Clevers H. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1996;86:391–399. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roose J, Molenaar M, Peterson J, Hurenkamp J, Brantjes H, Moerer P, van de Wetering M, Destrée O, Clevers H. The Xenopus Wnt effector XTcf-3 interacts with Groucho-related transcriptional repressors. Nature. 1998;395:608–612. doi: 10.1038/26989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arce L, Yokoyama NN, Waterman ML. Diversity of LEF/TCF action in development and disease. Oncogene. 2006;25:7492–7504. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staal FJ, Luis TC, Tiemessen MM. WNT signalling in the immune system: WNT is spreading its wings. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staal FJ, Sen JM. The canonical Wnt signaling pathway plays an important role in lymphopoiesis and hematopoiesis. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1788–1794. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Q, Sharma A, Oh SY, Moon HG, Hossain MZ, Salay TM, Leeds KE, Du H, Wu B, Waterman ML, et al. T cell factor 1 initiates the T helper type 2 fate by inducing the transcription factor GATA-3 and repressing interferon-gamma. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:992–999. doi: 10.1038/ni.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoverter NP, Waterman ML. A Wnt-fall for gene regulation: repression. Sci Signal. 2008;1:pe43. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.139pe43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verbeek S, Izon D, Hofhuis F, Robanus-Maandag E, te Riele H, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Wilson A, MacDonald HR, Clevers H. An HMG-box-containing T-cell factor required for thymocyte differentiation. Nature. 1995;374:70–74. doi: 10.1038/374070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mulroy T, Xu Y, Sen JM. beta-Catenin expression enhances generation of mature thymocytes. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1485–1494. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hossain MZ, Yu Q, Xu M, Sen JM. ICAT expression disrupts beta-catenin-TCF interactions and impairs survival of thymocytes and activated mature T cells. Int Immunol. 2008;20:925–935. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laurence A, Tato CM, Davidson TS, Kanno Y, Chen Z, Yao Z, Blank RB, Meylan F, Siegel R, Hennighausen L, et al. Interleukin-2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity. 2007;26:371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lundmark F, Duvefelt K, Iacobaeus E, Kockum I, Wallström E, Khademi M, Oturai A, Ryder LP, Saarela J, Harbo HF, et al. Variation in interleukin 7 receptor alpha chain (IL7R) influences risk of multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1108–1113. doi: 10.1038/ng2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bradley LM, Haynes L, Swain SL. IL-7: maintaining T-cell memory and achieving homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alves NL, van Leeuwen EM, Derks IA, van Lier RA. Differential regulation of human IL-7 receptor alpha expression by IL-7 and TCR signaling. J Immunol. 2008;180:5201–5210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lock C, Hermans G, Pedotti R, Brendolan A, Schadt E, Garren H, Langer-Gould A, Strober S, Cannella B, Allard J, et al. Gene-microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med. 2002;8:500–508. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gregory SG, Schmidt S, Seth P, Oksenberg JR, Hart J, Prokop A, Caillier SJ, Ban M, Goris A, Barcellos LF, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Group. Interleukin 7 receptor alpha chain (IL7R) shows allelic and functional association with multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/ng2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hafler DA, Compston A, Sawcer S, Lander ES, Daly MJ, De Jager PL, de Bakker PI, Gabriel SB, Mirel DB, Ivinson AJ, et al. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:851–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wielenga VJ, Smits R, Korinek V, Smit L, Kielman M, Fodde R, Clevers H, Pals ST. Expression of CD44 in Apc and Tcf mutant mice implies regulation by the WNT pathway. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:515–523. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65297-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baaten BJ, Li CR, Deiro MF, Lin MM, Linton PJ, Bradley LM. CD44 regulates survival and memory development in Th1 cells. Immunity. 2010;32:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cimmino L, Martins GA, Liao J, Magnusdottir E, Grunig G, Perez RK, Calame KL. Blimp-1 attenuates Th1 differentiation by repression of ifng, tbx21, and bcl6 gene expression. J Immunol. 2008;181:2338–2347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas RM, Chen C, Chunder N, Ma L, Taylor J, Pearce EJ, Wells AD. Ikaros silences T-bet expression and interferon-gamma production during T helper 2 differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2545–2553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.