Abstract

Using annual cross-sectional data from Monitoring the Future, the present study examined trends in high school seniors’ current and anticipated civic participation and beliefs over a 30-year period. We examined overall trends and patterns based on youths’ post-high school educational plans. Findings point to declines in recent cohorts’ involvement in conventional and alternative forms of engagement but greater involvement in community service. Regardless of period, the majority of youth said they intended to vote when eligible but few expressed trust in the government or elected officials. All civic indicators showed significant differences based on youths’ college aspirations: Youth who planned to graduate from a 4-year college were more civically inclined than their peers with 2-year or no college plans.

Adolescents are a barometer for the future of democracy, and over the past two decades, increased attention has been paid to the factors that engage young people in civic action. Yet, the extant work lacks a historical perspective, which is important for understanding the role of younger generations in political change. According to the life course principle of historical embeddedness, the period in which young people come of age is highly relevant to the formation of their civic identities (Elder, 1994; Stewart & McDermott, 2004). Social change occurs when younger cohorts carry these identities forward and replace their elders as voters and civic leaders (Lyons & Alexander, 2000). Thus, studying civic engagement across different historical periods and cohorts reveals the lens through which younger generations view their society and collectively contribute to shaping the body politic (Mannheim, 1952/1972). With this in mind, the present study examined trends over a 30-year period in U.S. high school seniors’ civic behaviors and beliefs. To determine whether these trends differ in relation to adolescents’ likely social class trajectories, we compared youths’ civic engagement based on their college aspirations. These analyses contribute to debates about whether certain forms of youth civic engagement have fallen out of favor over time, about whether political optimism or cynicism characterizes different generations of youth, and about whether the social class divide in civic engagement has widened.

Over the past decade, the conventional wisdom has been that youth have grown cynical about electoral politics, much as the empirical work with adults has suggested (Putnam, 2000). Galston (2002) argued that, in contrast to volunteer work through which young people feel they have an impact, many youth believe that conventional politics is ineffectual, slow, and unconnected to their deeper ideals. Among youth across nations, cynicism about the political process has been shown to undermine participation (Torney-Purta, Richardson, & Barber, 2004).

A civic divide in youths’ political and community involvement exists. In the United States, people with higher levels of education have historically participated in electoral politics and the civic affairs of their communities more than those with less education (Verba, Burns, & Schlozman, 2003). This civic divide in adult participation has roots in differential opportunities in young adulthood and in cumulative advantages in the pre-adult years (Flanagan & Levine, 2010). While some scholars fear this divide may have increased over the past several decades, this hypothesis has not been empirically tested (see National Conference on Citizenship, 2006).

When examining class differences in civic engagement, it is useful to distinguish groups of young people based on their college plans for two reasons. First, those not planning to obtain a college degree look demographically similar to individuals least likely to be civically engaged: racial and ethnic minorities, children of less educated parents, and individuals living in poorer neighborhoods (Verba et al., 2003). In contrast, youth who plan to obtain a college degree tend to come from financially stable families and have college-educated parents (Ellwood & Kane, 2000), and they are likely to have had more opportunities and encouragement to volunteer, vote, and participate in political conversations. Second, research suggests that public schools provide different opportunities for civic learning to college- and non-college-bound students. Comparisons of students in diverse academic tracking sequences have revealed that courses for college-bound students provided significantly more activities to build civic commitments and skills than did courses for their peers in lower academic tracks (Kahne & Middaugh, 2008). The communities in which disadvantaged youth grow up exacerbate these class differences: youth in high poverty school districts (from which college attendance is generally lower) have fewer opportunities to participate in service-learning and community outreach projects due to lack of resources and lower levels of political participation among adult role models (Hart & Atkins, 2002).

We examined 30-year trends in U.S. adolescents’ civic behaviors (conventional and alternative political activities as well as voting) and beliefs (trust in government and outlook for the world). Drawing on data collected over a period of three decades has the distinct advantage of allowing us to document historical patterns in youth civic engagement overall and to make comparisons based on youths’ college aspirations.

Method

Data come from Monitoring the Future, a study that has surveyed a nationally representative sample of high school seniors each year since 1976 (Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 2006). We use data spanning from 1976 to 2005. Measures come from survey forms 2 and 4; a different sample of approximately 3,000 students responded to a given question each year. Sample weights were used in all analyses to further ensure that findings are nationally representative of U.S. high school seniors. Weighted sample sizes for each analysis ranged from 81,447 to 92,538 (median N = 91,973). This repeated cross-sectional design (i.e., a different sample of high school seniors surveyed each year for 30 years) captures historical changes reflecting cohort and/or period effects, and cannot reflect changes within individuals or due to age.

Measures

Constructs were dichotomized to ease interpretation and simplify comparisons across items1.

Civic behaviors

Three items assessing conventional engagement asked whether participants had already done or planned to do the following: write to public officials, give money to a candidate or cause, and work in a political campaign. Voting in public elections was assessed by a single item. Two alternative engagement measures asked youth about participating in lawful demonstrations and boycotting certain products or stores. The response categories for all six of these items were Probably won’t do and Don’t know (both coded as 0), and Probably will do and Have already done (both coded as 1). Because many adolescents have not yet had opportunities to engage in some of these civic activities, behaviors and behavioral intentions were combined to create a category applicable to all participants. Community service was measured by a single item assessing frequency of participation in community affairs or volunteer work. The variable was recoded so that 0 = Never or A few times a year and 1 = Once or twice a month, At least once a week, or Almost everyday.

Trust and public hope

Trust in government was measured with two items: (a) “Do you think some of the people running the government are crooked?” [Response Range: None are crooked (1) to Quite a few are crooked (5)], and (b) “How much of the time do you think you can trust the government to do what is right?” [Response Range: Never (1) to Almost Always (5)]. The original 5–point response scales were dichotomized such that a score of 0 reflected distrust and 1 reflected trust in elected officials and the government. A single item assessed participants’ outlook for the world, or public hope: “When I think about terrible things, it is hard to hold much hope for the world.” This measure was recoded so that 0 = Neither agree nor disagree, Agree, or Mostly agree and 1 = Disagree or Mostly disagree.

Covariates

In addition to overall time trends in the civic indicators, analyses focused on differences in trends in terms of youths’ college aspirations. Based on responses to questions about 2-year and 4-year college attendance, adolescents were grouped into one of three mutually exclusive groups: youth with no college plans (i.e., definitely or probably will not go to 2- or 4-year college), youth with only 2-year college plans (i.e., definitely or probably will go to 2-year but not 4-year college), and youth with 4-year college plans (i.e., definitely or probably will go to 4-year college). All models controlled for sex and race.

Analytic Strategy

Each item was examined in a separate analysis using the generalized linear model with a logit link function to model a dichotomous distribution. Each regression model included explanatory variables of year (entered as a series of 29 dummy variables), sex (male vs. female), race (White, Black, and other), and college plans (4-year, 2-year, and no plans). Statistical significance for differences across the set of years was examined by calculating the likelihood ratio chi-square test comparing a full model to a model excluding dummy variables for year. Our approach treated year as a nominal variable to insure that we captured all variation over time, thereby avoiding any assumption of a specific linear or curvilinear form for these often complex time trends2. All time trends yielded significant improvement to model fit beyond the demographics of sex, race, and college aspirations (all likelihood ratio χ2 values exceed 359, df = 29, p’s < .001). Results presented in figures combine items that represent the same general construct (i.e., conventional engagement, alternative engagement, trust in government) for ease of presentation3.

Results

Forms of Civic and Political Engagement

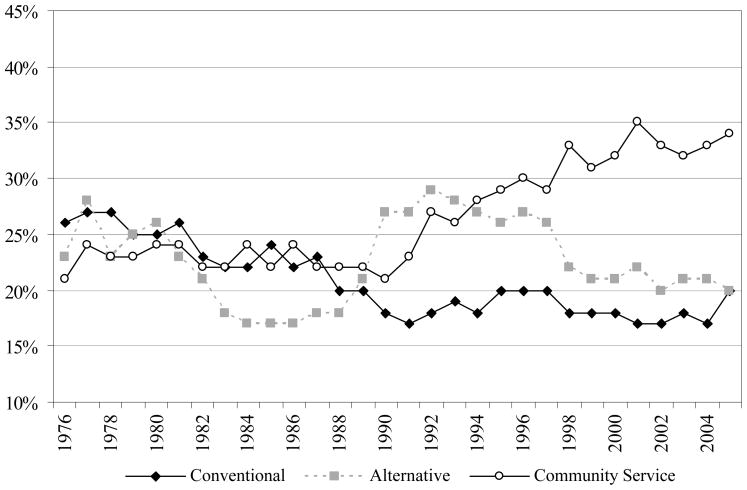

Consistent with popular perception, data revealed declines in adolescents’ conventional and alternative civic participation (see Figure 1). Trends in conventional participation peaked in 1977–1978 when 27% of youth said they had, or intended to, engage in conventional activities such as writing to public officials, giving money to political candidates or a cause, and working in a political campaign. From this time onward, conventional participation steadily waned until it reached its nadir in the first part of the new millennium (i.e., 2001–2002). Alternative forms of participation followed a similar trend during the early 1980s, falling precipitously from its near high of 28% in 1977 to a record low of 17% from 1984 to 1986. Subsequently, young people’s willingness to engage in alternative forms of engagement increased from 1989 (21%) to 1992 (29%) before the trend again receded towards a low of 20% in 2005. While alternative activities waxed and waned, conventional activities remained fairly stable with some decline between 1988 and 2004, before a slight upturn in 2005; across these years, 83–90% of youth reported that they intended to vote or had already voted.

Figure 1.

Trends in Youths’ Conventional, Alternative, and Community Service Participation.

Until 1990, the percentage of high school seniors who participated in community service at least once per month remained stable at around 23%, but participation increased steadily from 21% in 1990 to 34% by 2005. Examining trends in conventional, alternative, and community service participation in tandem (see Figure 1) revealed that in the last 15 years, high school seniors, on average, have been less and less likely to endorse alternative political engagement activities, their support for conventional political engagement remained considerably lower than in the previous 15 years, and yet they were increasingly likely to volunteer in their communities. With its stable high level, the trend in intention to vote is distinct from trends in other types of engagement.

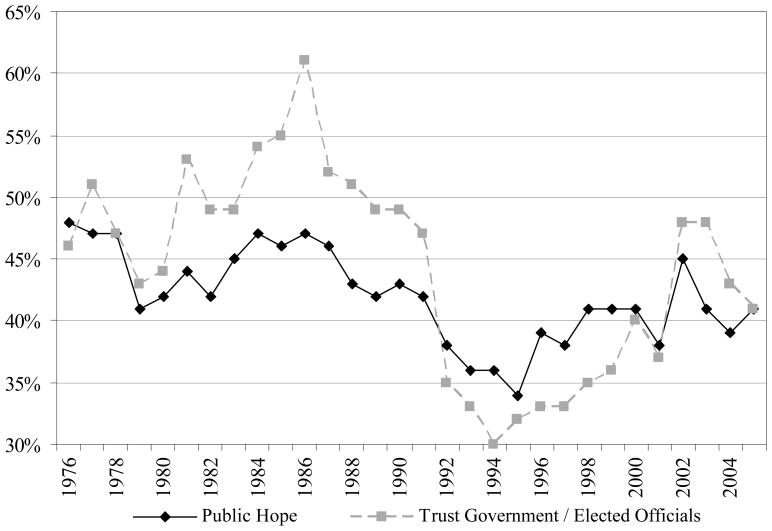

Trust in the Government and Public Hope

Regarding trust in the government, we found that in most years only a minority of high school seniors (average across years: 44%; range: 30–61%) believe that candidates for political office are honest and that the government can be trusted to do the right thing. As illustrated in Figure 2, trust in the government peaked in 1986 (61%) before dropping 31% to its lowest point in 1994, and then partially recovering across the 1990s. Youths’ outlook on the world oscillated between 34 and 48% over this same period. The trend in holding hope for the world was at its lowest in the mid-1990s, but recovered somewhat in the first part of the 2000s. Comparisons of these two trends, illustrated in Figure 2, revealed a strong similarity in trends over time (r = .85 between annual means), with peaks and valleys occurring in the same spans for both. Put simply, at times when young people on average felt the government and elected officials could be trusted, youth were also more likely to express a more hopeful outlook for the world.

Figure 2.

Trends in Youths’ Public Hope and Trust in Government and Elected Officials.

Differences in Trends by College Aspirations

Next, we examined trends in these same variables for high school seniors with 4-year, 2-year, and no college aspirations, controlling for race, sex, and the time trend. The coefficients are summarized in Table 1. Interactions between year and college aspirations were tested only for those civic indicators – voting and community service – where differences appeared to diverge over time.

Table 1.

Main Effects of College Aspirations for Civic Indicators.

| Beta | Odds Ratio | SE | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Engagement | ||||

| Write to public officials | ||||

| 4-year plans | 1.03 | 2.80 | .023 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .277 | 1.32 | .030 | <.001 |

| Give money to candidate or cause | ||||

| 4-year plans | .672 | 1.96 | .026 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .190 | 1.21 | .034 | <.001 |

| Work in a political campaign | ||||

| 4-year plans | 1.10 | 3.00 | .033 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .340 | 1.40 | .044 | <.001 |

| Voting | ||||

| 4-year plans | 1.42 | 4.14 | .026 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .627 | 1.87 | .032 | <.001 |

| Alternative Engagement | ||||

| Participate in lawful demonstration | ||||

| 4-year plans | .776 | 2.17 | .027 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .255 | 1.29 | .035 | <.001 |

| Boycott products or stores | ||||

| 4-year plans | .716 | 2.05 | .024 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .185 | 1.20 | .032 | <.001 |

| Community Service | ||||

| 4-year plans | .667 | 1.95 | .024 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .124 | 1.13 | .032 | <.001 |

| Trust in Government | ||||

| Officials are crooked (reversed) | ||||

| 4-year plans | .221 | 1.25 | .019 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .137 | 1.15 | .025 | <.001 |

| Government will do what is right | ||||

| 4-year plans | .573 | 1.77 | .020 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .216 | 1.24 | .026 | <.001 |

| Public Hope | ||||

| 4-year plans | .639 | 1.89 | .021 | <.001 |

| 2-year plans | .123 | 1.13 | .027 | <.001 |

Notes. Year (entered as a series of 29 dummy coded variables), race, and sex were included as categorical variables in all models, but effects are not shown. Reference groups: Youth with no college plans, White youth, and females.

Main effects

Across years, youth with aspirations to graduate from 4-year and 2-year colleges had higher odds of endorsing the whole range of civic indicators, compared to youth with no college aspirations. Table 1 summarizes findings from these analyses. Results showed that, compared to youth with no college plans, those with 4-year college plans had about two to three times greater odds of engaging (or planning to engage) in conventional and alternative civic activities. Likewise, they had four times greater odds of voting or intending to vote, compared to non-college-bound youth. They also had substantially (75% to 100%) higher odds of engaging in community service and holding hope for the world. Though also statistically significant, the difference in trust in government was modest (25% higher odds). While youth with 2-year college aspirations also had significantly higher odds of endorsing each of these civic indicators than youth with no college plans, the differences were considerably smaller than for those with 4-year aspirations. In fact, youth with 2-year plans had significantly lower odds of endorsing these civic behaviors and beliefs compared to youth with 4-year plans (ORs range from .45 to.92, all p’s < .001, not reported in Table 1). In sum, analyses revealed significant differences in civic behaviors and beliefs based on youths’ college aspirations: High school seniors who planned to attain a 4-year college degree had the highest civic engagement followed by their peers who planned to attain a 2-year college degree, with the lowest civic engagement reported by youth with no college plans.

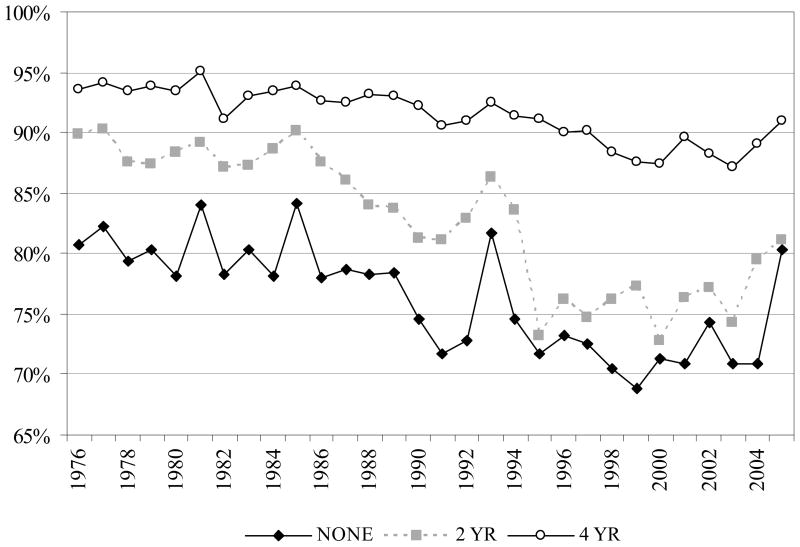

Differences in time trends

While voting trends for youth with 4-year and no college plans remained relatively stable across time, differing in level only, the trend for youth with 2-year plans declined since the mid-1980s (see Figure 3). We tested whether the gap between trends for youth with 4- and 2-year plans diverged across the 30-year period by entering interactions between year (linear term, centered at 1990) and youths’ college aspirations into the logistic regression. We chose linear time for this interaction in order to focus on a gradual and continuous divergence over the entire period. Compared to youth with 4-year college plans (i.e., the reference group) in 1990, youth with 2-year plans had 50% lower odds (OR = .51, p < .001), and youth with no college plans had 70% lower odds (OR = .29, p < .001) of endorsing voting. Interactions between college plans and the linear term for high school graduation year confirmed a significant widening between 1976 and 2005 in the gap in voting intentions between youth with 4- and 2-year college plans (β = −.013, SE = .004, p < .001), but not in the gap between those with 4-year and no college plans (β = −.001, SE =.003, p = .713). Indeed, while the trend for 4-year college aspirants showed a net decline of 3% across the 30 years, that for 2-year college aspirants declined by 9%, and by only 1% for youth with no college plans. In other words, although there has consistently been a gap in voting intentions based on youths’ college plans, from 1990 to 2005 the gap between youth with 4-year and 2-year plans has grown, thus suggesting a widening social class divide in voting intentions.

Figure 3.

Trends in Youths’ Intentions to Vote in Public Elections by College Aspirations.

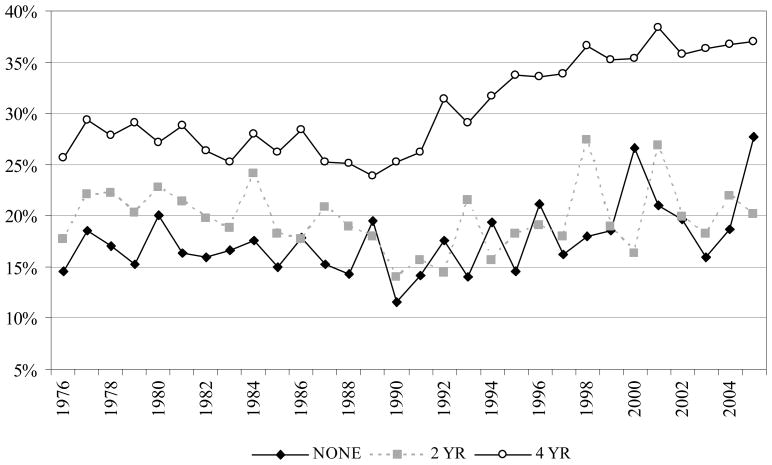

A similar growing gap appears in the community service trend. Since 1990, rates of community service participation for youth with 2-year college plans has slowed compared to that of their peers bound for 4-year colleges. We focus on the comparison of before versus after 1990 because the data suggested a relatively rapid rather than gradual change in this case. We tested the significance of this gap by adding interactions between year (dichotomously coded: pre-1990 = 0 vs. 1990 and later =1) and college aspirations in the logistic regression model. Results revealed a significant interaction between pre- versus post-1990 and 2-year college aspirations (β = − .358, SE = .051, p < .001) as well as no college plans (β = −.123, SE = .04, p = .002). As shown in Figure 4, community service levels were stable for all three groups between 1976 and 1990. Across these years, youth with 2-year plans had about 30% lower odds (OR = .710, p < .001) and youth with no college plans had about 40% lower odds (OR = .582, p < .001) of participating in community service compared to youth with 4-year college plans. Youth with no college plans, 2-year plans, and 4-year plans had average participations levels of 27%, 20%, and 18%, respectively. However, from 1991 to 2005, youth with 4-year plans showed a large and steady increase and ended at a higher level compared to the smaller and more volatile increases for youth with 2-year and no college plans. In 2005, 37% of youth with 4-year plans did community service, compared to 20% of youth with 2-year plans and 29% of youth with no college plans. Thus, although rates of community service increased for all youth, rates for youth with 4-year college aspirations increased considerably more than the rates for those with other post-high school plans, lending further evidence of a growing class divide in civic participation.

Figure 4.

Trends in Youths’ Community Service by College Aspirations.

Discussion

Our results indicate that over the past 30 years, high school seniors’ civic engagement has decreased in some areas and increased in others. Notably, the typical pattern of change was not the steady upward or downward trend often portrayed in commentaries on the civic lives of younger generations. Rather, patterns included multiple reversals and short-term plateaus. Our findings underscore the need for a historical perspective and suggest that snapshots of youths’ civic life need a wider interpretive lens.

Our data support the predominant view that recent cohorts of young people prefer volunteer work over participation in electoral politics. Since 1990, conventional and alternative participation have trended in opposite directions from community service. These trends likely reflect both the institutionalization of service-learning in high schools (National Youth Leadership Council, 2006) and the protracted transition to adulthood, which has led to a delay in conventional civic participation, such as voting (Flanagan & Levine, 2010). Finding that these indicators of civic engagement varied widely across the 30 years presents a sharp contrast to Trzesniewski and Donnellan’s (2010) analysis of these data, from which they concluded that historical cohort is not related to civic engagement. These discrepancies stem from differing analytic approaches used in the two analyses (see our footnote 2). Our approach is more open-ended in that we allowed the pattern of change to emerge from the data rather than assuming it would be linear. Our method allowed us to detect interesting and varied patterns missed by Trzesniewski and Donnellan.

Though young people’s trust in the government and elected officials has waxed and waned across the 30-year period, it has remained low throughout. As Torney-Purta and colleagues (2004) have argued, trust in the government relates to the stability of democracy and a degree of trust in the government is necessary to foster adolescents’ participation in their communities and politics. When trust is paired with trends in youths’ hope for the world, a fairly somber picture emerges, particularly during the mid-1990s. Even though we cannot discern a causal relationship, it is clear that youths’ trust in government and hopeful beliefs for the world are entwined. In fact, it has been noted that messages of hope during the 2008 presidential campaign resonated with young voters and motivated their increased engagement. Finding that more than half of youth find it hard to hold hope for the world and only slightly more than half trust the government to do what is right is disconcerting but provides additional context for understanding youths’ civic behaviors.

Comparisons based on high school seniors’ educational aspirations reveal unique insight into their civic behaviors and beliefs. For example, while community service increased for the sample as a whole, that growth was driven primarily by those planning to attend 4-year colleges. The institutionalization of graduation mandates for service likely accounts, in part, for the overall increase, while unequal access to opportunities to learn about and practice citizenship likely help explain the growing divide (e.g., Kahne & Middaugh, 2008). Similar disparities appeared with voting: youth with 2-year college plans increasingly look more like youth with no college plans than like their peers with 4-year plans when it comes to participating in the electoral process. Together these analyses provide new empirical evidence of a growing civic divide. Of course, these findings need to be considered in light of the likely change in the composition of youth with 4-year, 2-year, and no college plans over the past three decades, during which the need for a college education has increased. For example, between 1976 and 2005 the number of high school seniors aspiring to graduate from a 4-year college grew from 52% to 82%, while the proportion of those with 2-year college plans shrank from 16% to 10% and the proportion with no college plans shrunk from 32% to 8%. Although beyond the scope of this study, future research should also examine the role of changes in other demographics, such as the rise in Latino populations, on these trends. Regardless of the reason, a democratic society should be concerned by these trends, as they suggest we are preparing some youth to engage in politics and community affairs, while others are being left behind. Policymakers and civic educators should see these results as a wake-up call to find alternative ways to engage youth whose future plans do not include attaining a 4-year degree (see Zaff, Youniss, & Gibson, 2009).

When interpreting the results of this study, it is important to keep a few caveats in mind. First, though the Monitoring the Future datasets include a variety of items that assess young people’s civic engagement, they do not fully measure the breadth of participation. Civic engagement is continually being (re)invented by new cohorts of young people, often by taking advantage of technological innovations. Second, our measure of college plans reflects an aspiration, not an achievement. It is telling that plans alone so strongly differentiate civic behaviors and beliefs, perhaps because young people’s college aspirations are a central feature of their possible selves, identity, or place in the body politic. Parallel analyses were also conducted to examine whether trends based on youths’ college aspirations differed from trends based on parents’ education (i.e., high school diploma or less vs. more than a high school diploma). Very similar patterns emerged, despite the relatively low correlation between them (average phi correlation across years = .24; range .15 to .31). We presented comparisons based on youths’ college aspirations because they more clearly differentiate trends in the civic engagement measures, and because the formation of groups based on college plans provide more information about youth and their future orientations than does parents’ education, which focuses more on their origins. With that said, it is important to acknowledge that differences by college plans may be confounded with changes in the demographic profile of who plans to go to college and which college particular types of people aspire to attend.

Unlike previous studies that provide snapshots of adolescents’ civic life, our study illustrates the ways in which American adolescents, on average, have thought about and contributed to their communities and politics over the past 30 years. These historical trends, which tell a story of changing forms of civic engagement and a growing class divide, provide an important lens for developmental studies of adolescents’ civic engagement as well as for practitioners who work with youth in communities. As custodians of our democracy, it would behoove us, as a society, to reflect on these trends and consider how we can engage all young people – regardless of their college aspirations – and empower them with the skills, creativity, and hope necessary to be engaged citizens.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by The Network on Transitions to Adulthood, which was funded by The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The first and second authors’ time was supported by NIDA-funded National Research Service Awards (F31 DA 024916-01 and F31 DA 024543-01, respectively). The authors would like to thank Dr. James Cote for his thoughtful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Note. Ordinal models with the full response scales were also estimated, and they produced the same results. We chose to present the dichotomized response scales, as graphs of the percentages make the data more interpretable and accessible to a public audience.

Restricting attention to linear change, such as the approach used by Trzesniewski and Donnellan (2010), tests a narrower hypothesis that assumes change is a steady progression over time, moving up or down a fixed amount per year through the entire period. We do not make this assumption in our analyses and instead sought to characterize whatever pattern emerged. As illustrated in our figures, the change in our variables of interest were never linear.

We combined items for display in figures when items were similar in conceptual meaning and in patterns of trends over time. We judged trends similar only when the correlation over time between annual means exceeded.7.

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Conference on Emerging Adulthood (2007, February) in Tucson, Arizona.

Contributor Information

Amy K. Syvertsen, Email: amys@search-institute.org, Search Institute, 615 First Avenue NE, Suite 125, Minneapolis, MN 55413, Phone: (612) 692-5536.

Laura Wray-Lake, Email: Laura.Wray-Lake@cgu.edu, School of Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, Claremont Graduate University, 1227 N. Dartmouth Avenue, Claremont, CA 91711, Phone: 909-607-7813.

Constance A. Flanagan, Email: caflanagan@wisc.edu, School of Human Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Sterling Hall - Mailroom B605 475, N. Charter Street, Madison, WI 53706, Phone: (608) 262-2660.

D. Wayne Osgood, Email: wosgood@psu.edu, Department of Sociology, The Pennsylvania State University, 1002 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802-6207, Phone: (814) 865-1304.

Laine Briddell, Email: lbriddel@richmond.edu, Department of Sociology, University of Richmond, 28 Westhampton Way, University of Richmond, VA 23173, Phone: (804) 287-6430.

References

- Elder GH., Jr Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1994;57:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood DT, Kane TJ. Who is getting a college education? Family background and the growing gaps in enrollment. In: Danziger S, Waldfogel J, editors. Securing the future: Investing in children from birth to college. New York: Russell Sage; 2000. pp. 283–324. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan C, Levine P. Civic engagement and the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children. 2010;20:1550–1558. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galston WA. Civic education and political participation. PS: Political Science & Politics. 2004;37:263–266. doi: 10.1017/S1049096504004202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hart D, Atkins R. Civic competence in urban youth. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:227–236. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0604_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM. Monitoring the Future: A continuing study of the lifestyles and values of youth (12th Grade Survey), 1977–2005. [Data file]. Conducted by University of Michigan, Survey Research Center. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kahne J, Middaugh E. Democracy for some: The civic opportunity gap in high school (Working Paper 59) College Park, MD: CIRCLE; 2008. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- Lyons W, Alexander R. The tale of two electorates: Generational replacement and the decline of voting in presidential elections. The Journal of Politics. 2000;62:1014–1034. doi: 10.1111/0022–3816.00044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim K. The problem of generations. In: Kecskemeti P, editor. Essays on the sociology of knowledge. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1972. pp. 276–322. Original work published in 1952. [Google Scholar]

- National Conference on Citizenship. America’s civic health index: Broken engagement. Report by The National Conference on Citizenship in association with CIRCLE and Saguaro seminar; Washington, DC: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Youth Leadership Council. The national survey on service-learning and transitioning to adulthood. New York: Harris Interactive; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Shuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AJ, McDermott C. Civic engagement, political identity, and generation in developmental context. Research in Human Development. 2004;1:189–203. doi: 10.1207/s15427617rhd0103_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torney-Purta J, Richardson WK, Barber CH. Trust in government-related institutions and civic engagement among adolescents: Analyses of five countries from the IEA Civic Education Study (Working Paper 14) College Park, MD: CIRCLE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB. Rethinking “Generation Me”: A study of chort effects from 1976–2006. Perspectives on Psychology Science. 2010;5:58–75. doi: 10.1177/1745691609356789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verba S, Burns N, Schlozman KL. Unequal at the starting line: Creating participatory inequalities across generations and among groups. The American Sociologist. 2003;34:45–69. doi: 10.1007/s12108-003-1005-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaff JF, Youniss J, Gibson CM. An inequitable invitation to citizenship: Non-college-bound youth and civic engagement. Denver, CO: Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement (PACE); 2009. [Google Scholar]