Abstract

The centrosome is a major microtubule-organizing center in animal cells, and its intracellular positioning is critical for defining intracellular architecture. The centrosome positions itself at the cell center. Centrosome centration depends on the microtubule cytoskeleton. To accomplish robust centration regardless of the cell size or cell shape, it has been assumed that the force mediated by the microtubules depends on microtubule length. However, a concrete mechanism to generate forces to pull the centrosome in a microtubule length-dependent manner has been elusive. Recently, we successfully demonstrated that centrosome-directed movement of intracellular organelles along microtubules drives centrosome centration in the Caenorhabditis elegans early embryo. Based on this observation, we proposed the centrosome-organelle mutual pulling model in which the reaction forces of organelle transport generated along microtubules act as a driving force that pulls the centrosomes toward the cell center. This is the first experiment-based model that accounts for the microtubule length-dependent pulling force generated in the cytoplasm contributing to centrosome centration. Intriguingly, this model is consistent with a recent estimation that the pulling force is proportional to the cubic length of microtubules.

Key words: centrosome centration, microtubule length dependency, dynein, centrosome-organelle mutual pulling model

The Emergence of Order in Cell Architecture

The cell can be compared to a city. A population of macromolecules lives their lives inside the cell, and they utilize the network of cytoskeleton proteins as highways. An important similarity between the cell and spontaneously emerged cities is that, even though individuals (molecules or humans) act selfishly and lack a rigid and global design plan, the resultant system as a whole (cells or cities) has an astonishing degree of spatial order and harmony. Some architects, as Yoshinobu Ashihara, have been interested in the emergence of such order in cities and discussed the issue with an analogy to cells.1 Understanding the mechanisms underlying the spatial organization of cells should thus contribute not only to understanding cell function but also to understanding the design principles of natural and artificial architecture.

Positioning of the Centrosome at the Cell Center

Defining the center should be the foundation for any type of architecture. Regarding the cell, it is widely known that the cell nucleus is positioned at the cell center. The central positioning of the chromosome-containing nucleus is important for segregating genetic materials equally into daughter cells upon cell division. The central positioning of the nucleus is accomplished by the function of the centrosome.2 The centrosome is a major microtubule-organizing center in animal cells, and it functions to position itself at the cell center. Centrosome centration is important not only for the central positioning of the nucleus but also for a variety of intracellular organization functions such as organelle positioning and defining the cell division plane.3,4 The centrosome is not always positioned at the center. Positioning of the centrosome away from the center is observed during asymmetric cell division or cell migration.2,5 The mechanism of centrosome centration is important for understanding the off-center positioning of the centrosome. Indeed, the center-directed force is included in the modeling studies of the off-center positioning of centrosomes.6,7

The Mechanism of Centrosome Centration

How can the centrosome move toward and remain at the cell center? Because the central positioning is a widespread feature of cells, we believe the underlying mechanism is conserved across different species. Centrosome centration depends mostly on the microtubule cytoskeleton.4,8

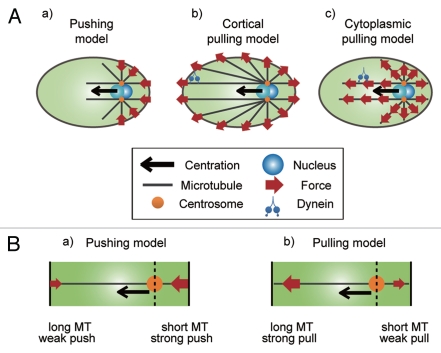

Because the centration depends on filamentous microtubules, the candidate mechanisms can be roughly divided into pushing and pulling mechanisms (Fig. 1).9–11 The pushing mechanism utilizes pushing force produced by microtubule polymerization against the cell cortex. When the growing end (“plus-end”) of the microtubule reaches and pushes against the cell cortex, the reaction force from the cortex pushes the microtubule back. The force is then transmitted through the microtubule to the other end (“minus-end”) of the microtubule where the centrosome is located. Therefore, the centrosome experiences repulsive force from the cortex [Fig. 1A(a)]. The pulling mechanism utilizes minus-end-directed motor protein activity or microtubule depolymerization.11 If minus-enddirected motor proteins are fixed at a certain structure and steps along the microtubules toward the minus-end (i.e., the centrosome), the centrosome is pulled toward the motor proteins. Similarly, if the plus-end of the microtubule is anchored to a certain structure and the microtubule depolymerizes (from the plus-end), the centrosome is pulled toward the plus-end. The pulling may occur at cortex [Fig. 1A(b)], or at cytoplasm [Fig. 1A(c)].

Figure 1.

Possible mechanisms of centrosome centration. [A(a)] The pushing model. The plusends of the growing microtubules can push the cell cortex to move the centrosome away from the cortex. [A(b)] The cortical pulling model. The centrosome centration anchors are located at the cortex and pull astral microtubules. [A(c)] The cytoplasmic pulling model. The centrosome centration anchors are distributed equally throughout the cytoplasm. (B) Microtubule-length dependency in the pushing or pulling force. [B(a)] In the pushing model, shorter microtubules should produce larger pushing forces to promote movement toward the cell center. [B(b)] In the pulling models, longer microtubules should produce larger pulling forces.

Importantly, to move toward and stop at the cell center, the amount of force exerted on each microtubule must be dependent on microtubule length (Fig. 1B). In the pushing mechanism, shorter microtubules should produce greater pushing forces than longer microtubules [Fig. 1B(a)]. In contrast, in the pulling mechanism, longer microtubules should produce greater pulling forces [Fig. 1B(b)].

Pushing Mechanism: Microtubule Length Dependency and Experimental Support

The pushing mechanism utilizes pushing force produced when growing microtubules push against the cell cortex [Fig. 1A(a)]. This pushing force has been demonstrated to be stronger when the microtubule is shorter in vitro.12 This property of microtubules is theoretically feasible because the maximum pushing force mediated by elastic rods such as microtubules should not exceed the buckling force. Longer rods are weaker and buckle with a force inversely proportional to the square of the rod's length. The pushing force mediated by microtubules should be weaker for longer microtubules and thus account for the centration of centrosomes.9,11,13,14

The pushing mechanism has been demonstrated to be sufficient for centrosome centration in vitro.15 In living cells, yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae16 and Schizosaccharomyces pombe13 use the pushing mechanism to position the spindle pole body (SPB; the centrosome counterpart in yeast) at the cell center. It has long been believed that the pushing mechanism is the major mechanism involved in centrosome centration in general.17 However, the pushing mechanism is unlikely to be the major mechanism for animal cells, as we discuss in the next section. The size of the cell may affect whether the pushing mechanism contributes majorly because long microtubules in large cells may not be able to exert sufficiently large forces to move the centrosome due to weak buckling forces.10

Pulling Mechanism: Microtubule Length Dependency and Experimental Support

The pulling mechanism uses minus-end-directed motor proteins or microtubule depolymerization to produce forces to pull the centrosome toward the plus-end of the microtubule [Fig. 1A(b and c)]. The pulling mechanism is supported by two lines of evidences. First, Hamaguchi and Hiramoto demonstrated that the centrosome is positioned at the center of the microtubule-active region independent of the cell cortex.18 On the basis of this observation, they proposed a cytoplasmic pulling model for centrosome centration [Fig. 1A(c)]. Second, a minus-end-directed motor protein, cytoplasmic dynein, is required for centrosome centration in various species such as mammalian cultured cells19 and C. elegans embryos.20 Without the activity of dynein, centrosomes do not move toward the center, although microtubules polymerize and appear to push the cortex.20 It is believed that the pulling mechanism is the major driving force for centrosome centration in animal cells.14

Here, one remaining mystery has been the location where the pulling force that moves the centrosome to the cell center is generated, i.e., which structure inside the cell functions as a substrate to anchor force generators (i.e., dynein or the plus-end of microtubules).9,21–23 We refer to the structure as the “centrosome centration anchor.”24 The centrosome centration anchor may be located at the cell cortex [Fig. 1A(b)] or throughout the cytoplasm [Fig. 1A(c)]. To solve this mystery, both identification of the centrosome centration anchor and how the generated force depends on microtubule length (L) [Fig. 1B(b)] should be considered. Importantly, a recent analysis combining systematic shape changes of sea urchin zygotes and theoretical modeling estimated that the amount of pulling force is proportional to the cubic length of microtubules (L3).4

Pulling at the Cortex

In most cells, the major localization of dynein is at the cell cortex.23 Therefore, a straightforward mechanism to generate pulling force for centrosome centration is that the centrosome centration anchor is located at the cell cortex.19 However, a simple cortical pulling mechanism in which every microtubule reaching the cortex is pulled with a constant force cannot produce force dependent on microtubule length (Fig. 2A). Several ideas have been proposed to overcome this problem and produce force dependent on microtubule length with pulling at the cortex.

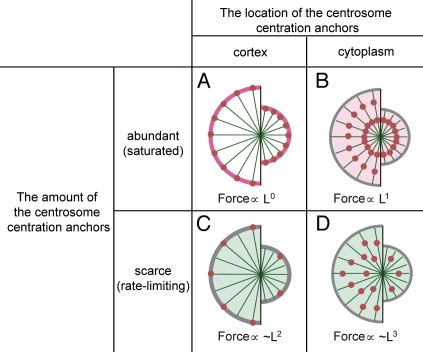

Figure 2.

Microtubule-length dependency of the amount of force. The number of force generators is abundant (A and B) or scarce (C and D) compared to the number of microtubules. The force generators are located at the cortex (A and C) or throughout the cytoplasm (B and D). Microtubules are shown in green, and the centrosome centration anchors are shown in red. The left hemisphere of each part represents the longer microtubule scenario. (A) When microtubules reaching the cortex are pulled with a constant force, the force per microtubule does not depend on its length. (B) When microtubules are pulled in the cytoplasm, where the centrosome centration anchors are abundant, the number of anchors contacting a microtubule should be proportional to the length of the microtubule (L1). Similar length dependency should appear when the cell is flat and the anchors are abundant and located at the cortex (the servomechanical model).23 (C) When the anchors are rate-limiting, the probability of microtubules to encounter the anchor is proportional to the surface area they cover21 and thus would be roughly proportional to the square length of microtubules (L2).25 (D) When cytoplasmic anchors are rate-limiting, the probability of microtubules to encounter the anchor is proportional to the volume they cover and thus be proportional to the cubic length of microtubules (L3).4

A force generator-limited model accounts for the production of length-dependent pulling force with cortical anchors.21 If the number of centrosome centration anchors is scarce and rate-limiting, the amount of pulling force depends not on the number of microtubules but on the surface area of the cortex in the direction of movement (Fig. 2C). Because the anticipated number of anchors to contact a single microtubule is proportional to the surface area covered by the microtubule, the force on a single microtubule should be roughly proportional to the squared length of the microtubule (L2).25 The assumption that the pulling force generator is limited in number is based on an experimental estimation.26

A “servomechanical model”23 assumes that in flat cells, microtubules elongate along the cell cortex until they reach the lateral cell boundaries. In this model, the number of centrosome centration anchors associated with a microtubule depends roughly on the distance between the centrosome (i.e., minus-end of the microtubule) and the lateral cell boundaries (i.e., plus-end) and thus on microtubule length. The force mediated by a single microtubule should be proportional to its length (L1) when centrosome centration anchors are abundant compared to the number of microtubules (Fig. 2B and see legend) or be proportional to the square of its length (L2) when these anchors are scarce (Fig. 2C).25

Another possible mechanism for length-dependent pulling at the cortex involves the length-dependent depolymerization of microtubules. The kinesin-8 family of motor protein has been demonstrated to depolymerize microtubules in a microtubule-length-dependent manner.27 If the plus-end of a microtubule is anchored at the cell cortex, microtubule depolymerization should pull the centrosome toward the cell cortex.11,28 Therefore, microtubule-length-dependent depolymerization can be a mechanism for centrosome centration, although there has been no experimental support for the actual involvement of this mechanism in centrosome centration thus far.

It is still questionable whether pulling at the cortex actually contributes to centrosome centration. In sand dollar eggs, centrosome centration occurs in a cortex-independent manner.18 In large amphibian eggs, the microtubules do not reach the cell cortex in the traveling direction during centrosome centration.22 In C. elegans, the major molecules involved in anchoring dynein at the cell cortex are dispensable for centrosome centration.7

Pulling in the Cytoplasm

The centrosome centration anchor may be located throughout the cytoplasm [Fig. 1A(c)]. If this is the case, the pulling force per microtubule should increase as the length of the microtubule increases because longer microtubules should be in greater contact with the anchors [Figs. 1B(b), 2B and D].9 This length-dependent pulling in the cytoplasm was initially proposed by Hamaguchi and Hiramoto in sand dollar eggs.18 In a computer simulation assuming that the anchors are located in the cytoplasm, the in vivo profile of centrosome centration was reproduced in C. elegans.14 The requirement of such a mechanism was supported by observations in early amphibian and fish embryonic cells where cells are so large that the plus-ends of microtubules hardly reach the cell cortex during centrosome centration.3 However, no reports have elucidated the actual structure in the cytoplasm that anchors cytoplasmic dynein to pull the centrosomes.

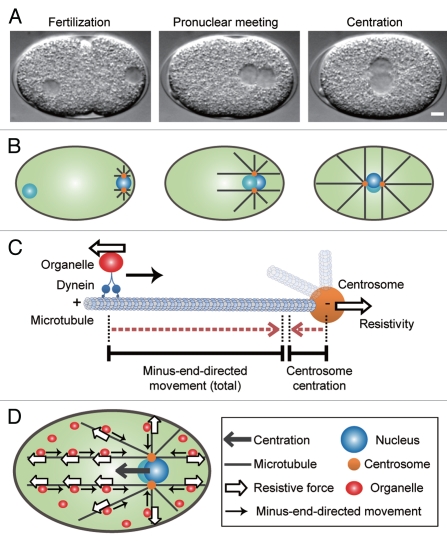

The Centrosome-Organelle Mutual Pulling Model as an Underlying Model for the Cytoplasmic Pulling Mechanism

Recently, we proposed a new mechanism for centrosome centration (Fig. 3).24 We first screened candidate genes involved selectively in the centrosome centration anchor in C. elegans embryos (Fig. 3A and B) and found DYRB-1, a light chain subunit of the cytoplasmic dynein complex. Interestingly, DYRB-1 was also required for the minus-end-directed movement of organelles, such as endosomes, lysosomes and yolk granules. Because DYRB-1 was selectively required for centrosome centration and organelle movement, we suspected a causal relationship between the two processes in a way that intracellular organelles associated with dynein serve as the centrosome centration anchor. To test this hypothesis, we knocked down genes involved in minus-end-directed organelle transport, such as rilp-1, rab-7 and rab-5. Importantly, knockdown of these genes impaired centrosome centration but not other dynein-dependent processes. On the basis of these experimental results, we proposed a mutual pulling model in which organelles function as cytoplasmic anchors to generate pulling forces for centrosome centration (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3.

The centrosome-organelle mutual pulling model for centrosome centration.24 (A) Differential interference contrast images of the 1-cell stage C. elegans embryo during centrosome centration. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) Schematic representation of the movements of centrosomes during centrosome centration in the C. elegans embryo. The right and left sides of the embryo are the posterior and anterior sides, respectively. After fertilization, the centrosomes and associated male pronucleus (blue circle) begin migrating from the posterior cortex toward the center of the cell. The centrosome-male pronucleus complex meets the female pronucleus (light blue circle) in the posterior, and then the complex reaches the center of the cell. (C) The centrosome-organelle mutual pulling model. When dynein transports organelles toward the centrosome along microtubules, a resistive force is generated as a driving force that pulls the centrosome. Consequently, both the dynein-organelle complex and the centrosome move toward each other. (D) Overview of the mutual pulling model. A resistive force of organelle transport driven by dynein via microtubules depends on microtubule length because the organelles are distributed equally throughout the cell. This mutual pulling mechanism positions the centrosomes at the center of the cell.

The idea that intracellular organelles comprise the centrosome centration anchor in the cytoplasm has been previously speculated.9 The major objection to such an idea was that because there is also plus-end-directed movement of organelles, the net force produced by the movements of plus-end- and minus-end-directed organelles may be zero.23 However, based on our theoretical estimation of the force balance, a very small number of minus-end-directed organelle movements should be sufficient for centering.24 Thus, if the number of minus-end-directed movements slightly exceeds the number of plus-end-directed movements, sufficient force would be generated to move the centrosome. Consistent with this idea, we observed less plus-end-directed movements of the organelles than minus-end-directed movements in wild-type cells of C. elegans embryos.24

The Centrosome-Organelle Mutual Pulling Model Accounts for the Volume-Sensing Mechanism

Investigation of nuclear stretching in microfablicated chambers of defined geometry estimated that the pulling force was nearly proportional to the cubic length of the microtubules (L3).4 As the underlying mechanism, the authors of the report proposed a “volume-sensing” model in which the motor proteins are located throughout the cytoplasm but are limited in number (Fig. 2D).4 The centrosome-organelle mutual pulling model is consistent with this volume-sensing model not only because force generation occurs throughout the cytoplasm but also because the force generation event (i.e., the frequency of minus-end-directed organelle movements) was scarce in our observation of C. elegans embryos.24

Implications of the Centrosome-Organelle Pulling Model in Off-Center Positioning of the Centrosome

The centrosome is occasionally positioned off-center. This off-center positioning is important for the polarization of the cell and thus, for asymmetric cell division, cell migration and cell differentiation.2,5 Because the organelle movement along the microtubule takes place in most cells, we believe that the centrosome centration force generated by the centrosome-organelle pulling model functions even during off-center positioning of the centrosome. In such cells, in addition to the centration force, asymmetric forces such as microtubule-pulling forces from a localized cortical region29 are generated to accomplish off-center positioning. In this scenario, the centration force may buffer against asymmetric forces to prevent excessive movement of the centrosome.7 Alternatively, the centrosome-organelle mutual pulling model might be involved in the off-center positioning of the centrosome in a more direct manner. If we consider that organelles are asymmetrically distributed within a cell, then the pulling forces from the organelles should not balance at the cell center but should balance at an off-center position. Currently, no experimental data are available to support this scenario, but asymmetric localization of organelles has been reported.30 It will be intriguing to determine whether and how organelle transport is involved in the off-center positioning of centrosomes.

Future Perspectives

Centrosome centration is a fundamental feature of cell architecture. Recent studies established that cytoplasmic pulling is a major driving force for centrosome centration in (some) animal cells. Of course, there may be other mechanisms involved in this centration. Recent theoretical analysis demonstrated that a combination of microtubule-based pushing and pulling mechanisms, and an actin-based mechanism collectively contributes to robust centralization.31 In fish melanophore cells, pigment granules are aggregated at the cell center in a centrosome-independent manner.32 The depolymerization of microtubules at the minus-ends (treadmilling) is proposed to drive this centration.33 One future direction of the study of defining the cell center may be the characterization of the distinct mechanisms involved and evaluation of their relative contributions in actual cells.

An interesting aspect of centrosome centration is that this macroscopic order is established not only by the assembly of macromolecules (such as microtubules) but also by the environment (such as cell size and shape). In constructing cells, the bottom-up assembly of macromolecules has been well-documented in previous studies. In addition, the environment or physicochemical field, where the molecules are placed significantly affects the assembly of the molecules and thus the spatial organization of the cell. Returning to the analogy between cells and cities, our cities do not look similar, although the basic components are similar. This is because geography and climate vary by location. Similarly, interplay between molecular assembly and the physicochemical environment should establish the commonality and diversity in cell architecture and thus in cell function. We believe that the study of centrosome centration is a good model to study this interplay and thus promote our understanding of cell architecture.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shuichi Onami, under whose mentorship A.K. began studying the mechanism of centrosome centration. We also thank Yuki Hara and Takeshi Sugawara for commenting on the manuscript. Studies in the Kimura lab are supported by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and by the Transdisciplinary Research Integration Center of the Research Organization of Information and Systems, Japan.

References

- 1.Ashihara Y. The hidden order. Tokyo: Kodansha International; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke B, Roux KJ. Nuclei take a position: managing nuclear location. Dev Cell. 2009;17:587–597. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wühr M, Tan ES, Parker SK, Detrich HW, 3rd, Mitchison TJ. A model for cleavage plane determination in early amphibian and fish embryos. Curr Biol. 2010;20:2040–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minc N, Burgess D, Chang F. Influence of cell geometry on division-plane positioning. Cell. 2011;144:414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaughan S, Dawe HR. Common themes in centriole and centrosome movements. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pecreaux J, Roper JC, Kruse K, Jülicher F, Hyman AA, Grill SW, et al. Spindle oscillations during asymmetric cell division require a threshold number of active cortical force generators. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2111–2122. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura A, Onami S. Local cortical pulling-force repression switches centrosomal centration and posterior displacement in C. elegans. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1347–1354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strome S, Wood WB. Generation of asymmetry and segregation of germ-line granules in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1983;35:15–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinsch S, Gönczy P. Mechanisms of nuclear positioning. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2283–2295. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.16.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dogterom M, Kerssemakers JW, Romet-Lemonne G, Janson ME. Force generation by dynamic microtubules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura A, Onami S. Modeling microtubule-mediated forces and centrosome positioning in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 2010;97:437–453. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(10)97023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogterom M, Yurke B. Measurement of the force-velocity relation for growing microtubules. Science. 1997;278:856–860. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tran PT, Marsh L, Doye V, Inoue S, Chang F. A mechanism for nuclear positioning in fission yeast based on microtubule pushing. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:397–411. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura A, Onami S. Computer simulations and image processing reveal length-dependent pulling force as the primary mechanism for C. elegans male pronuclear migration. Dev Cell. 2005;8:765–775. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holy TE, Dogterom M, Yurke B, Leibler S. Assembly and positioning of microtubule asters in microfabricated chambers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6228–6231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw SL, Yeh E, Maddox P, Salmon ED, Bloom K. Astral microtubule dynamics in yeast: a microtubule-based searching mechanism for spindle orientation and nuclear migration into the bud. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:985–994. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chambers EL. The Movement of the Egg Nucleus in Relation to the Sperm Aster in the Echinoderm Egg. J Exp Biol. 1939;16:409–424. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamaguchi MS, Hiramoto Y. Analysis of the role of astral rays in pronuclear migration in sand dollar eggs by the colcemid-UV method. Develop Growth and Differ. 1986;28:143–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1986.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burakov A, Nadezhdina E, Slepchenko B, Rodionov V. Centrosome positioning in interphase cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:963–969. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gönczy P, Pichler S, Kirkham M, Hyman AA. Cytoplasmic dynein is required for distinct aspects of MTOC positioning, including centrosome separation, in the one cell stage Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:135–150. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grill SW, Hyman AA. Spindle positioning by cortical pulling forces. Dev Cell. 2005;8:461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wühr M, Dumont S, Groen AC, Needleman DJ, Mitchison TJ. How does a millimeter-sized cell find its center? Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1115–1121. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.8.8150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallee RB, Stehman SA. How dynein helps the cell find its center: a servomechanical model. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura K, Kimura A. Intracellular organelles mediate cytoplasmic pulling force for centrosome centration in the Caenorhabditis elegans early embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:137–142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013275108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hara Y, Kimura A. Cell-size-dependent spindle elongation in the Caenorhabditis elegans early embryo. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1549–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grill SW, Howard J, Schaffer E, Stelzer EH, Hyman AA. The distribution of active force generators controls mitotic spindle position. Science. 2003;301:518–521. doi: 10.1126/science.1086560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varga V, Helenius J, Tanaka K, Hyman AA, Tanaka TU, Howard J. Yeast kinesin-8 depolymerizes microtubules in a length-dependent manner. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:957–962. doi: 10.1038/ncb1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozlowski C, Srayko M, Nédélec F. Cortical microtubule contacts position the spindle in C. elegans embryos. Cell. 2007;129:499–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grill SW, Gönczy P, Stelzer EH, Hyman AA. Polarity controls forces governing asymmetric spindle positioning in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Nature. 2001;409:630–633. doi: 10.1038/35054572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews R, Ahringer J. Asymmetry of early endosome distribution in C. elegans embryos. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu J, Burakov A, Rodionov V, Mogilner A. Finding the cell center by a balance of dynein and myosin pulling and microtubule pushing: a computational study. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:4418–4427. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodionov VI, Borisy GG. Self-centring activity of cytoplasm. Nature. 1997;386:170–173. doi: 10.1038/386170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malikov V, Cytrynbaum EN, Kashina A, Mogilner A, Rodionov V. Centering of a radial microtubule array by translocation along microtubules spontaneously nucleated in the cytoplasm. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/ncb1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]