Abstract

Intermediate filaments (IFs) form cytoplamic and nuclear networks that provide cells with mechanical strength. Perturbation of this structural support causes cell and tissue fragility and accounts for a number of human genetic diseases. In recent years, important additional roles, nonmechanical in nature, were ascribed to IFs, including regulation of signaling pathways that control survival and growth of the cells, and vectorial processes such as protein targeting in polarized cellular settings. The cytolinker protein plectin anchors IF networks to junctional complexes, the nuclear envelope and cytoplasmic organelles and it mediates their cross talk with the actin and tubulin cytoskeleton. These functions empower plectin to wield significant influence over IF network cytoarchitecture. Moreover, the unusual diversity of plectin isoforms with different N termini and a common IF-binding (C-terminal) domain enables these isoforms to specifically associate with and thereby bridge IF networks to distinct cellular structures. Here we review the evidence for IF cytoarchitecture being controlled by specific plectin isoforms in different cell systems, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, lens fibers, lymphocytes, myocytes, keratinocytes, neurons and astrocytes, and discuss what impact the absence of these isoforms has on IF cytoarchitecture-dependent cellular functions.

Key words: plectin, epidermolysis bullosa simplex, cytolinker protein, intermediate filament, cytoarchitecture, vimentin, desmin, keratin

Plectin is considered as a universal crosslinking element of the cytoskeleton.1 Possessing binding sites for all types of intermediate filament (IF) subunit proteins, it networks IFs by interlinking them and anchoring them to transmembrane junctional complexes, the nuclear envelope and cytoplasmic organelles. In addition, plectin harbors a functional actin-binding domain and binds to microtubules (MTs). There is overwhelming evidence that IF networking through plectin contributes to the stability and coherence of cells, as most convincingly documented by the skin blistering and muscular dystrophy phenotype exhibited by patients suffering from epidermolysis bullosa with muscular dystrophy (EBS-MD) and gene-targeted mice. The role of plectin's interaction with actin and MTs remains less clear. In fact the observations that plectin deficiency favors actin stress fiber formation and reduces MT dynamics suggest a regulatory rather than stabilizing role of plectin in actin and tubulin assembly processes.

Plectin is a multimodular cytolinker protein of gigantic size (>500 kDa) with several dozens of verified interaction partners. Its two globular multi-interactive end domains are separated by an α-helical sequence that dimerizes with another molecule to form a 190 nm-long coiled-coil rod domain. Plectin's IF-binding site was delineated to a stretch of 50 amino acid residues residing in its C-terminal domain. A special peculiarity of plectin is its isoform diversity based on the differential splicing of over a dozen alternative first exons into a common exon 2, giving rise to a variety of transcripts that encode different isoforms just varying in short N-terminal sequences. These variable sequences determine the cellular targeting of the isoforms. Plectin's isoforms show preferential binding and thus association with a variety of different cellular structures, including hemidesmosomes (HDs), focal adhesions (FAs) and costameres, mitochondria, MTs, nuclear/ER membranes or Z-disks; others probably still have to be identified. As all of these isoforms are equipped with a C-terminal high-affinity IF-binding site, they can mediate the targeting and anchorage of IFs at different, clearly defined cellular locations. In this way, depending on the combination of plectin isoforms expressed in a certain type of cell or tissue and at a certain stage of development or differentiation, IF network architecture will vary. In what follows we will discuss the evidence leading up to and providing future perspectives for a model in which plectin isoform-controlled IF cytoarchitecture not only affects the integrity of distinct cell types and tissues and influences some of their basic cellular functions, including polarization, migration and differentiation, but also serves for the fine-tuning and compartmentalization of signaling pathways.

Plectin's Influence on Vimentin IF Cytoarchitecture

From early on plectin was proposed to play an important role in IF network organization and to act as a crosslinker of vimentin filaments, as reflected by its chosen name.2,3 Later it was found that plectin not only was important for IF network-plasma membrane linkage, but also seemed to be involved in the regulation of IF dynamics.4 Monitoring the dynamics of vimentin networks in spreading and dividing mouse fibroblasts, it was shown that plectin is associated with vimentin from the early stages of filament assembly and is required for the formation of filament intermediates and their directional movement towards the cell periphery. Moreover, plectin deficiency makes fibroblasts pass faster through mitosis than wild-type cells and leads to a more even partitioning of vimentin networks to the daughter cells. Strikingly, this correlates with a more even size of postmitotic daughter cells, which in wild-type fibroblasts were found to differ in size (occupied area of cells) by a factor of almost three.5 Both phenomena, faster mitotic progression and more balanced distribution of IFs, are probably due to the fact that cells containing more loosely networked vimentin (as in the case of plectin-null cells) more readily undergo the structural reorganization that takes place during mitosis and cytokinesis.

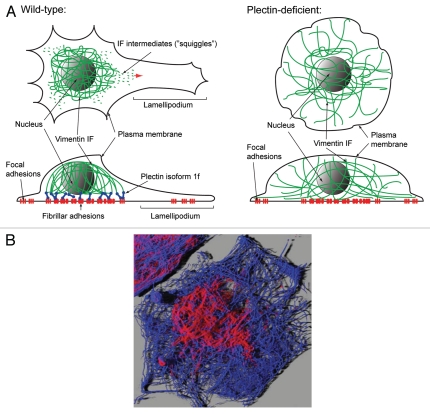

Recent studies have shown that plectin is involved in de-novo IF network formation and FA turnover.6 Forming tight connections between fibroblasts and their underlying extracellular matrix, FAs are located at both ends of actin/myosin-containing contractile stress fibers.7,8 Plectin was identified as a FA constituent already in 1992.9 Against expectations, plectin-deficient (plectin−/−) fibroblasts showed an increase in the numbers of FAs and stress fibers.10 Plectin 1f (P1f), one of several plectin isoforms expressed in fibroblasts, was shown to be an integral component of FA-evolved fibrillar adhesions (FbAs), which are characterized by their elongated structure and central cellular localization.11,12 P1f stabilizes these structures and turns them into recruitment sites for motile vimentin filament intermediates. Thus, immobilized filament intermediates lead to IF assembly via end-to-end fusion with mobile precursors and integration into a central IF network (note vimentin intermediates—so-called “squiggles”—in Figure 1A, moving towards the cell periphery and integrating into the existing, cage-like vimentin network). In this scenario the nucleus is encased and positioned by the central IF network which is firmly anchored into centrally located FbAs and thus stably connected to the exterior of the cell (Fig. 1A, wild-type; and B). In contrast, the more peripheral FAs, which are not associated with IFs and have a much faster (∼2.7-fold) turnover, are actively engaged in cell motility and formation of protrusions. The formation and plectin-dependent anchorage of the central core structure strongly affects cell shape and polarization, as revealed in an analysis of wild-type and plectin−/− fibroblast cell geometries. Although there were no differences observed for the average cell area of either cell type, plectin+/+ fibroblasts had more protrusions and a more polarized shape compared to the more rounded plectin−/− cells, correlating with a more extended and less compact IF network in these cells. In particular, the vimentin network in plectin−/− fibroblasts was not restricted to the central part of the cell like in plectin+/+ cells, but was extending to the outermost boundary of the cells, where the filaments were often found to bend at their distal ends along the plasma membranes6 (and unpublished data; compare fibroblast cytoarchitecture in wild-type and plectin-deficient cells as schematically depicted in Fig. 1A). Aberrant vimentin network organization includes lateral bundling of filaments and loosening of network compactness, making the network more susceptible to stress-induced disruption and okadaic acid-induced retraction (unpublished data).

Figure 1.

(A) Model of plectin's function as organizer and stabilizer of fibroblast cytoarchitecture. Schematic representation of a polarized fibroblast cell depicting the central localization of the vimentin IF network encasing the nucleus through its attachment to FbAs and centrally located FAs. The attachment of the IF network is mediated by plectin isoform 1f. Note the presence of vimentin filament intermediates (“squiggles”). On their way to the cell periphery (red arrow), they will be “captured” by FA-associated P1f and by tandem-fusion will extend filaments that eventually will be integrated into the centrally located cage-like network. In plectin-deficient cells, which are rounded and not polarized, the vimentin network is not restricted to the central part of the cell, but is extending to the outermost boundary of the cell. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy of primary mouse fibroblasts. Microtubules are depicted in blue, vimentin IFs in red. A maximum-intensity projection of a confocal Z-stack in the “easy 3D” mode in Imaris 4.5 software (Bitplane) is shown. Note the perinuclear cage-like vimentin core (Image: Gerald Burgstaller, University of Vienna, Max F. Perutz Laboratories, Vienna, Austria; with permission of Molecular Biology of the Cell).

Altered cytoarchitecture in plectin−/− fibroblasts results in compromised signaling (decreased Src and FAK activities) leading to a decreased migration potential10 (unpublished data). Moreover, plectin−/− fibroblasts have been shown to be less stiff than their wild-type counterparts. They have lost the capacity to propagate mechanical stress over long cytoplasmic distances and display reduced traction forces, demonstrating a direct connection between the plectin-vimentin network and stiffness, stress propagation and traction generation of cells.13

Plectin-controlled vimentin IF organization has been shown to play also an important role in endothelial cell systems. Similar to fibroblasts, it was found that in primary plectin−/− lung endothelial cells vimentin filaments were more bundled combined with an increased mesh size of the IF network (unpublished data). In contrast to their wild-type counterparts, immortalized (p53−/−) plectin-deficient endothelial cells showed a dramatic rearrangement (collapse) of their IF network when treated with the nitric oxid-donor drug SNAP.14 This suggested that plectin provides the IF network in these cells with robustness, showing for the first time that plectin can have a protective impact on IFs against oxidative stress. Moreover, it has been reported that vimentin filament recruitment to FAs of endothelial cells requires plectin and integrin β3,15 and Homan et al.16 suggested that plectin mediates the connection of the filaments to a vimentin-associating integrin α6β4-based endothelial junctional complex. Vimentin IF anchorage to the underlying substratum has been shown to play a pivotal role in reinforcing endothelial cell adhesion, thus enabling these cells to resist shear stress under flow conditions.17 Consistent with these observations, vimentin-deficient mice showed attenuated flow-induced dilatation of their mesenteric arteries.18 Thus, it is quite conceivable that hemorrhagic blisters frequently observed in EBS-MD patients19 and the extensive paw bleedings observed with plectin-deficient newborn mice20 are a consequence of increased vascular fragility, an intriguing prospect that needs further exploration.

Another tissue of great interest in the context of plectin-controlled vimentin network architecture and its potential impact on cellular functions are lens fiber cells. Since long it has been known that plectin is expressed at high levels in this tissue and constitutes a prominent component of the subplasma membrane protein skeleton.21,22 Thus we predict that vimentin IF cytoarchitecture in developing lens fiber cells is strongly dependent on plectin, especially its membrane-associating isoforms. It will also be of interest to explore whether the plectin-mediated alterations in vimentin network architecture affect fiber cell maturation and whether beaded filaments found in mature lens fibers interact with plectin, and if so, whether vimentin and beaded filaments interact with the same set of plectin isoforms.

One of the isoforms of plectin, P1, which is expressed in a variety of tissues, is most prominent in those of mesenchymal origin, including connective tissue, vascular, eye lens and white blood cells. Dermal fibroblasts isolated from P1−/− mice (deficient in just this but none of the other isoforms), similar to plectin-null fibroblasts, exhibited abnormalities in their actin cytoskeleton and impaired migration potential.23 Similarly, when T lymphocytes, in which plectin has been suggested to act as an important organizer of cytoarchitecture,24 were isolated from P1−/− mice, they displayed a diminished chemotactic in vitro migration potential compared to their wild-type counterparts. Most strikingly, on the organismic level it was found that leukocyte infiltration during wound healing was reduced, clearly indicating a role of plectin, specifically isoform P1, in immune cell motility.23 Uncovering the molecular mechanisms underlying P1/vimentin IF-regulated cell motility of immune and other types of mesenchym-derived cells presents an interesting challenge for future research. It is of interest in this context that studies in muscle tissue indicate that P1 is a major linker component between IFs and the nuclear/ER membrane (see below). Thus, P1 is also likely the isoform of plectin that docks on to the outer nuclear membrane protein nesprin-3, establishing a continuous connection between the nucleus and the extracellular matrix through the IF cytoskeleton,25 with the luminal nuclear envelope and nesprin-binding protein torsinA being part of this axis.26

Another isoform of plectin prominantly expressed in connective tissue as well as other types of cells is P1b. Carrying a mitochondrial targeting and anchoring signal in its N-terminal isoform-specific sequence, P1b inserts into the outer membrane of the organelle, thus bridging it to the IF network. In primary fibroblasts and myoblasts derived from P1b isoform-deficent mice the mitochondria were found to have undergone substantial shape changes. It was proposed that P1b forms a signaling platform on the mitochondrial surface and affects shape and network formation of the organelle by tethering it to IFs.27 Although P1b does not necessarily affect IF network cytoarchitecture by itself, architectural features and the compartimentalization of the network under the control of other isoforms, such as those linking it to the plasma membrane or nuclear envelope, will affect the spatial distribution and local positioning of the organelles.

Plectin Isoforms as the Key to Desmin IF Network Architecture and Skeletal Muscle Integrity

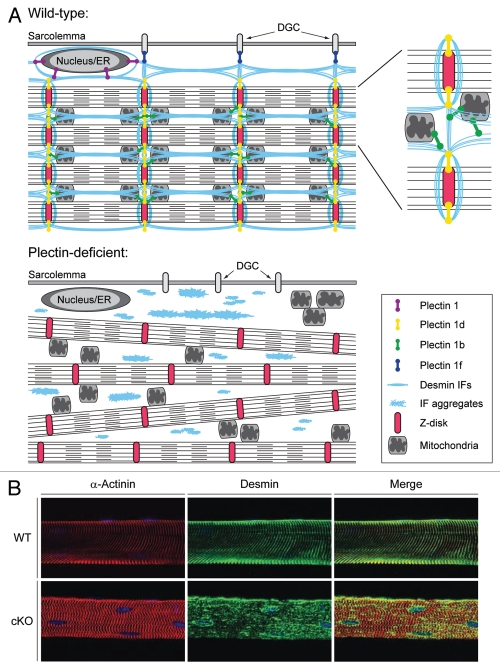

Plectin's influence on IF network organization is most prominent in skeletal muscle fibers, which loose their integrity in its absence. The major IF network in striated muscle is formed from desmin filaments. Extending throughout the extrasarcomeric space these filaments encircle myofibrils at the level of Z-disks and extend to the sarcolemma and intercalated disks, integrating nuclei, mitochondria and other organelles in their network.28 Plectin has been visualized in association with desmin filaments interlinking neighboring myofibrils and to mitochondria at the level of Z-disks and along the entire length of the sarcomere (see schematic illustration shown in Fig. 2A, wild-type). Thus, plectin colocalizes with desmin at structures forming the intermyofibrillar and the subplasma membrane protein scaffolds.20, 29–32 Most mutations in the human plectin gene cause EBS-MD.33 EBS-MD is characterized by severe skin blistering and late-onset, progressive muscular dystrophy. Plectin-deficient mice reveal abnormalities reminiscent of minicore myopathies in skeletal muscle and disintegration of intercalated disks in heart, but as they die within 2–3 days after birth due to internal blistering of the oral cavity that disallows food uptake, they are of limited use as animal models for EBS-MD.20,34 The phenotypic analysis of conditional (MCK-Cre) striated muscle-restricted plectin knockout mice was more revealing, showing progressive degenerative alterations including aggregation and partial loss of desmin IFs along with the detachment of the contractile apparatus from the sarcolemma.35 Overall, desmin-deficient and plectin-deficient mice show similar phenotypes, including detachment of the contractile apparatus from the sarcolemma, profound changes in myofiber costameric cytoarchitecture and decreased mitochondrial number and functions (Fig. 2A, plectin-deficient; and B). However, due to the additional formation of dysfunctional protein (desmin) aggregates in subplasma membrane and interior cellular compartments, the hallmark of myofibrillar myopathies, generally the phenotypes of plectin-null myofibers are more severe than those of desmin-null myofibers.

Figure 2.

(A) Scheme depicting plectin's role in skeletal muscle fibers. Different plectin isoforms bind to desmin IFs and interlink myofibrils with each other and the costameric lattice. Note the disctint anchoring functions of the four major plectin isoforms expressed in muscle. Plectin 1d, 1f, 1b, and 1 interlink desmin IFs with Z-disks, costameres (dysctroglycan complex, DGC), mitochondria, and the outer nuclear/ER membrane system, respectively. Plectin-deficiency causes detachment of desmin IFs from Z-disks, costameres, mitochondria and nuclei. Progressive degenerative alteration including massive desmin aggregation and misalignment of Z-disks can be observed. A more detailed scheme showing the localization and binding partners of isoforms P1d and P1b in the extrasarcomeric space between two Z-disks structures is shown in the upper right corner. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy of teased EDL muscle fibers from 4-month-old wildtype and muscle-specific conditional plectin knock-out (cKO) mice revealed massive longitudinal desmin aggregates (green) and misaligned α-actinin-positive Z-disks (red) in cKO mice.

Four isoforms of plectin, P1, P1b, P1d and P1f were found to be expressed at substantial levels in skeletal muscle.36 Immunofluorescence microscopy of transfected cells and teased muscle fibers revealed that they are targeted to distinct subcellular locations.37,38 P1d associates with Z-disks, P1f with the sarcolemmal dystrophin-glycoprotein complex, P1b with mitochondria and P1 with the outer nuclear/ER membrane system. In targeting desmin IFs to these structures, P1d and P1f turned out to be crucial for linking the contractile apparatus as a whole via desmin IFs to the sarcolemmal costameric protein skeleton (the different anchoring functions of distinct plectin isoforms are depicted in Fig. 2A).35 Disruption of one (P1d) or both (P1f and P1d) of these IF linking elements inevitable leads to the loss of muscle fiber integrity, as demonstrated by isoform (P1d)-specific gene targeting or conditional plectin gene knockout in mice.35

Plectin, Keratin Cytoarchitecture and MT Dynamics

Similar to the alterations in vimentin organization observed in plectin−/− fibroblasts, in plectin-deficient keratinocytes the keratin filaments appear more bundled and less flexible compared to wild-type cells, leading to IF networks of less delicate appearance and greater mesh size.39 While in plectin+/+ cells, hardly any IFs were found at the cell margins leaving a filament-free ring-shaped zone at the periphery, in plectin-deficient keratinocytes IF networks were extending further to the periphery. As a consequence, keratin networks become more susceptible to osmotic shock-induced retraction from peripheral areas, and their disruption due to hyperphosphorylation (okadaic acid-induced) proceeds faster. Interestingly, contrary to the migratory phenotype observed in plectin-deficient fibroblasts, plectin−/− keratinocytes showed increased migration rates correlating with significantly elevated basal activities of the MAP kinase Erk1/2 and of the membrane associated upstream protein kinases c-Src and PKCδ.39

The lack of plectin leads to a disruption of the keratin cytoskeleton linkage to HDs,20,40 the transmembrane junctional complexes that mediate the firm attachment of basal cell layer keratinocytes to the underlying basement membrane.41 One of several isoforms of plectin expressed in keratinocytes, P1a, binds directly and in an isoform-specific manner to the major hemidesmosomal transmembrane laminin receptor complex integrin α6β4. Thus P1a mediates the stable anchorage of basal cell layer keratinocytes by linking the intracellular IF network system to the extracellular matrix. Assembly and disassembly of HDs play an important role in keratinocyte migration during differentiation and wound healing. Binding of plectin to integrin α6β4 turned out to be a critical step in HD formation.40,42 Moreover, during Ca2+-activated differentiation, P1a interacts with the Ca2+-sensing protein calmodulin, resulting in diminished plectin-integrin β4 binding.43 Thus as an early step, dissociation of plectin from integrin β4 seems key to keratinocyte differentiation and likely plays an important role in HD disassembly and dynamics.

As a second major plectin isoform expressed in primary keratinocytes, P1c was found to partially colocalize with MTs.44 Preliminary studies indicate that P1c favors MT dynamics and has a destabilizing effect on keratinocyte MTs (unpublished data). This opens the intriguing perspective that keratin network-associated plectin regulates MT dynamics in a spatially controlled manner. Thus plectin isoform-controlled cytoarchitecture leading to IF network compartmentalization may locally regulate MT-dependent cellular processes via P1c.

Plectin's Influence on Other Types of IF Networks and Possible Consequences

Our knowledge about plectin's influence on IF architecture and possible consequences for the functions of cells that express IF network types differing from those built of vimentin, desmin or keratins, is still limited. Plectin has been shown to interact with all three neurofilament (NF) subunit proteins in vitro3 and to show widespread occurrence in neural cells and tissues.45 Furthermore, it was reported early on that neurodegeneration can accompany EBS-MD.46 The phenotypic analysis of isoform-specific (P1c) knockout mice revealed a trend toward larger distances between NFs in P1c−/− L5 ventral root axons leading to slightly reduced NF densities. A highly interesting phenotype observed in these isoform-specific as well as in conditional (neuronal precursor cell-specific) nestin-Cre/plectin knock-out mice was a significantly reduced nerve conduction velocity (NCV) in sciatic nerve.47 It will be a challenging task for future research to investigate whether alterations in NCV and NF cytoarchitecture are mechanistically linked, or alternatively, whether P1c-controlled MT dynamics (see above) influence NCV. Regarding glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-containing IF networks, insufficient amounts of plectin have been shown to promote GFAP aggregation in astrocytes, the hallmark of Alexander disease.48 Furthermore, primary astroglial cells lacking plectin show a delay in cAMP-stimulated morphological differentiation.10 Plectin was reported to interact in vitro also with lamin B, one of the three major IF components of the nuclear lamina.49 The biological significance of this interaction remains to be investigated. In view of its proposed role as architectural and networking element of IFs, functioning as a scaffolding platform for nuclear envelope proteins during mitosis seems a plausible hypothesis to be tested.

Plectin as a Scaffolding Platform in Signaling

Versatile molecular interactions and strategic cellular localization encourage the model of plectin as a mechanical stabilizer of cells by acting as a multifunctional linker and scaffolding protein in different cell types. However, beyond its mechanical support function, plectin acts as a cytoskeletal scaffolding platform that provides binding sites for proteins involved in signaling. Among others, plectin was shown to bind and sequester the receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) to the cytoskeleton, thereby influencing PKC signaling pathways,50 with effects on MAP kinase pathways.39 In fact, it has been shown for fibroblasts as well as keratinocytes, that when plectin is missing, RACK1 looses its perinuclear location and accumulates at the plasma membrane where it affects signaling pathways involving PKC and c-Src, creating a situation similar to that of wild-type cells stimulated via external signals, such as EGF. Additionally, plectin scaffolds were shown to recruit energy-controlling AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in differentiated myofibers.51 Plectin-interacting proteins and molecules involved in signaling include phosphatidyl-inositol-4,5-biphosphate (PIP2),10 calmodulin,43 nesprin-3,25 the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Fer,52 and the laminin receptors β-dystroglycan,38 integrin α6β4,40 and integrin α7β1 (unpublished data).

In conclusion, in view of plectin's universal role as regulator of IF network architecture and its consequences for the dynamics of other cytoskeletal filament systems, cell-internal and plasma membrane-located junctional complexes, cell polarity and cell migration, one can expect a wide spectrum of signaling pathways to be affected by plectin/IF systems.

Acknowledgements

Work from the authors' laboratory cited as unpublished was supported by grants from the Austrian Science Research Fund, Multilocation DFG-Research Unit 1228 and DEBRA, UK.

Abbreviations

- IF

intermediate filament

- MT

microtubule

- EBS-MD

epidermolysis bullosa with muscular dystrophy

- HD

hemidesmosome

- FA

focal adhesion

- FbA

fibrillar adhesion

- P1

P1a, P1b, P1c, P1d, P1f, plectin isoform 1, 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d and 1f, respectively

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- NF

neurofilament

- NVC

nerve conduction velocity

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- RACK1

receptor for activated C kinase 1

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- PIP2

phosphatidyl-inositol-4,5-biphosphate

References

- 1.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiche G, Baker MA. Cytoplasmic network arrays demonstrated by immunolocalization using antibodies to a high molecular weight protein present in cytoskeletal preparations from cultured cells. Exp Cell Res. 1982;138:15–29. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(82)90086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foisner R, Leichtfried FE, Herrmann H, Small JV, Lawson D, Wiche G. Cytoskeleton-associated plectin: in situ localization, in vitro reconstitution and binding to immobilized intermediate filament proteins. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:723–733. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinböck FA, Nikolic B, Coulombe PA, Fuchs E, Traub P, Wiche G. Dose-dependent linkage, assembly inhibition and disassembly of vimentin and cytokeratin 5/14 filaments through plectin's intermediate filament-binding domain. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:483–491. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spurny R, Gregor M, Castañón MJ, Wiche G. Plectin deficiency affects precursor formation and dynamics of vimentin networks. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:3570–3580. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgstaller G, Gregor M, Winter L, Wiche G. Keeping the vimentin network under control: cell-matrix adhesion-associated plectin 1f affects cell shape and polarity of fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:3362–3375. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abercrombie M, Dunn GA. Adhesions of fibroblasts to substratum during contact inhibition observed by interference reflection microscopy. Exp Cell Res. 1975;92:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(75)90636-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burridge K, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. Focal adhesions, contractility and signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:463–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seifert GJ, Lawson D, Wiche G. Immunolocalization of the intermediate filament-associated protein plectin at focal contacts and actin stress fibers. Eur J Cell Biol. 1992;59:138–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrä K, Nikolic B, Stöcher M, Drenckhahn D, Wiche G. Not just scaffolding: plectin regulates actin dynamics in cultured cells. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3442–3451. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamir E, Katz BZ, Aota S, Yamada KM, Geiger B, Kam Z. Molecular diversity of cell-matrix adhesions. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1655–1669. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.11.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zamir E, Katz M, Posen Y, Erez N, Yamada KM, Katz BZ, et al. Dynamics and segregation of cell-matrix adhesions in cultured fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:191–196. doi: 10.1038/35008607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Na S, Chowdhury F, Tay B, Ouyang M, Gregor M, Wang Y, et al. Plectin contributes to mechanical properties of living cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:868–877. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00604.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spurny R, Abdoulrahman K, Janda L, Rünzler D, Köhler G, Castañón MJ, et al. Oxidation and nitrosylation of cysteines proximal to the intermediate filament (IF)-binding site of plectin: effects on structure and vimentin binding and involvement in IF collapse. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8175–8187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharya R, Gonzalez AM, Debiase PJ, Trejo HE, Goldman RD, Flitney FW, et al. Recruitment of vimentin to the cell surface by beta3 integrin and plectin mediates adhesion strength. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1390–1400. doi: 10.1242/jcs.043042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Homan SM, Mercurio AM, LaFlamme SE. Endothelial cells assemble two distinct alpha6beta4-containing vimentin-associated structures: roles for ligand binding and the beta4 cytoplasmic tail. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2717–2728. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.18.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuruta D, Jones JC. The vimentin cytoskeleton regulates focal contact size and adhesion of endothelial cells subjected to shear stress. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4977–4984. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henrion D, Terzi F, Matrougui K, Duriez M, Boulanger CM, Colucci-Guyon E, et al. Impaired flow-induced dilation in mesenteric resistance arteries from mice lacking vimentin. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2909–2914. doi: 10.1172/JCI119840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer JW, Rouan F, Kofler B, Rezniczek GA, Kornacker I, Muss W, et al. A compound heterozygous one amino-acid insertion/nonsense mutation in the plectin gene causes epidermolysis bullosa simplex with plectin deficiency. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:617–625. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrä K, Lassmann H, Bittner R, Shorny S, Fässler R, Propst F, et al. Targeted inactivation of plectin reveals essential function in maintaining the integrity of skin, muscle and heart cytoarchitecture. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3143–3156. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weitzer G, Wiche G. Plectin from bovine lenses. Chemical properties, structural analysis and initial identification of interaction partners. Eur J Biochem. 1987;169:41–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiche G. Plectin: general overview and appraisal of its potential role as a subunit protein of the cytomatrix. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1989;24:41–67. doi: 10.3109/10409238909082551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrahamsberg C, Fuchs P, Osmanagic-Myers S, Fischer I, Propst F, Elbe-Bürger A, et al. Targeted ablation of plectin isoform 1 uncovers role of cytolinker proteins in leukocyte recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18449–18454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505380102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown MJ, Hallam JA, Liu Y, Yamada KM, Shaw S. Cutting edge: integration of human T lymphocyte cytoskeleton by the cytolinker plectin. J Immunol. 2001;167:641–645. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilhelmsen K, Litjens SH, Kuikman I, Tshimbalanga N, Janssen H, van den Bout I, et al. Nesprin-3, a novel outer nuclear membrane protein, associates with the cytoskeletal linker protein plectin. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:799–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nery FC, Zeng J, Niland BP, Hewett J, Farley J, Irimia D, et al. TorsinA binds the KASH domain of nesprins and participates in linkage between nuclear envelope and cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3476–3486. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winter L, Abrahamsberg C, Wiche G. Plectin isoform 1b mediates mitochondrion-intermediate filament network linkage and controls organelle shape. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:903–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capetanaki Y, Bloch RJ, Kouloumenta A, Mavroidis M, Psarras S. Muscle intermediate filaments and their links to membranes and membranous organelles. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2063–2076. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiche G, Krepler R, Artlieb U, Pytela R, Denk H. Occurrence and immunolocalization of plectin in tissues. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:887–901. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.3.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hijikata T, Murakami T, Imamura M, Fujimaki N, Ishikawa H. Plectin is a linker of intermediate filaments to Z-discs in skeletal muscle fibers. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:867–876. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reipert S, Steinböck F, Fischer I, Bittner RE, Zeöld A, Wiche G. Association of mitochondria with plectin and desmin intermediate filaments in striated muscle. Exp Cell Res. 1999;252:479–491. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schröder R, Warlo I, Herrmann H, van der Ven PF, Klasen C, Blumcke I, et al. Immunogold EM reveals a close association of plectin and the desmin cytoskeleton in human skeletal muscle. Eur J Cell Biol. 1999;78:288–295. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(99)80062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiaverini C, Charlesworth A, Meneguzzi G, Lacour JP, Ortonne JP. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex with muscular dystrophy. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ackerl R, Walko G, Fuchs P, Fischer I, Schmuth M, Wiche G. Conditional targeting of plectin in prenatal and adult mouse stratified epithelia causes keratinocyte fragility and lesional epidermal barrier defects. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2435–2443. doi: 10.1242/jcs.004481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konieczny P, Fuchs P, Reipert S, Kunz WS, Zeöld A, Fischer I, et al. Myofiber integrity depends on desmin network targeting to Z-disks and costameres via distinct plectin isoforms. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:667–681. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fuchs P, Zörer M, Rezniczek GA, Spazierer D, Oehler S, Castañón MJ, et al. Unusual 5′ transcript complexity of plectin isoforms: novel tissue-specific exons modulate actin binding activity. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2461–2472. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rezniczek GA, Abrahamsberg C, Fuchs P, Spazierer D, Wiche G. Plectin 5′-transcript diversity: short alternative sequences determine stability of gene products, initiation of translation and subcellular localization of isoforms. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3181–3194. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rezniczek GA, Konieczny P, Nikolic B, Reipert S, Schneller D, Abrahamsberg C, et al. Plectin 1f scaffolding at the sarcolemma of dystrophic (mdx) muscle fibers through multiple interactions with beta-dystroglycan. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:965–977. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osmanagic-Myers S, Gregor M, Walko G, Burgstaller G, Reipert S, Wiche G. Plectin-controlled keratin cytoarchitecture affects MAP kinases involved in cellular stress response and migration. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:557–568. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rezniczek GA, de Pereda JM, Reipert S, Wiche G. Linking integrin alpha6beta4-based cell adhesion to the intermediate filament cytoskeleton: direct interaction between the beta4 subunit and plectin at multiple molecular sites. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:209–225. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones JC, Hopkinson SB, Goldfinger LE. Structure and assembly of hemidesmosomes. Bioessays. 1998;20:488–494. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199806)20:6<488::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koster J, van Wilpe S, Kuikman I, Litjens SH, Sonnenberg A. Role of binding of plectin to the integrin beta4 subunit in the assembly of hemidesmosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1211–1223. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kostan J, Gregor M, Walko G, Wiche G. Plectin isoform-dependent regulation of keratin-integrin alpha6beta4 anchorage via Ca2+/calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18525–18536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andrä K, Kornacker I, Jörgl A, Zörer M, Spazierer D, Fuchs P, et al. Plectin-isoform-specific rescue of hemidesmosomal defects in plectin (−/−) keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:189–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Errante LD, Wiche G, Shaw G. Distribution of plectin, an intermediate filament-associated protein, in the adult rat central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 1994;37:515–528. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490370411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith FJ, Eady RA, Leigh IM, McMillan JR, Rugg EL, Kelsell DP, et al. Plectin deficiency results in muscular dystrophy with epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Genet. 1996;13:450–457. doi: 10.1038/ng0896-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuchs P, Zörer M, Reipert S, Rezniczek GA, Propst F, Walko G, et al. Targeted inactivation of a developmentally regulated neural plectin isoform (plectin 1c) in mice leads to reduced motor nerve conduction velocity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26502–26509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tian R, Gregor M, Wiche G, Goldman JE. Plectin regulates the organization of glial fibrillary acidic protein in Alexander disease. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:888–897. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foisner R, Traub P, Wiche G. Protein kinase A- and protein kinase C-regulated interaction of plectin with lamin B and vimentin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3812–3816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osmanagic-Myers S, Wiche G. Plectin-RACK1 (receptor for activated C kinase 1) scaffolding: a novel mechanism to regulate protein kinase C activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18701–18710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gregor M, Zeöld A, Oehler S, Marobela KA, Fuchs P, Weigel G, et al. Plectin scaffolds recruit energy-controlling AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in differentiated myofibres. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1864–1875. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lunter PC, Wiche G. Direct binding of plectin to Fer kinase and negative regulation of its catalytic activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:904–910. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]