Abstract

We describe a patient with asymptomatic apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (AHCM) who later developed cardiac arrhythmias, and briefly discuss the diagnostic modalities, differential diagnosis and treatment option for this condition. AHCM is a rare form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy which classically involves the apex of the left ventricle. AHCM can be an incidental finding, or patients may present with chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea, syncope, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, embolic events, ventricular fibrillation and congestive heart failure. AHCM is frequently sporadic, but autosomal dominant inheritance has been reported in few families. The most frequent and classic electrocardiogram findings are giant negative T-waves in the precordial leads which are found in the majority of the patients followed by left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy. A transthoracic echocardiogram is the initial diagnostic tool in the evaluation of AHCM and shows hypertrophy of the LV apex. AHCM may mimic other conditions such as LV apical cardiac tumors, LV apical thrombus, isolated ventricular non-compaction, endomyocardial fibrosis and coronary artery disease. Other modalities, including left ventriculography, multislice spiral computed tomography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imagings are also valuable tools and are frequently used to differentiate AHCH from other conditions. Medications used to treat symptomatic patients with AHCM include verapamil, beta-blockers and antiarrhythmic agents such as amiodarone and procainamide. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator is recommended for high risk patients.

Keywords: Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Electrocardiogram

INTRODUCTION

Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (AHCM) is a rare form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) which usually involves the apex of the left ventricle and rarely involves the right ventricular apex or both[1]. Historically, this condition was thought to be confined to the Japanese population but it is also found in other populations. Of all the HCM patients in Japan the prevalence of AHCM was 15%, whereas in USA the prevalence was only 3%[2].

CASE REPORT

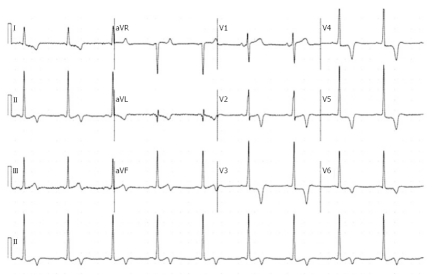

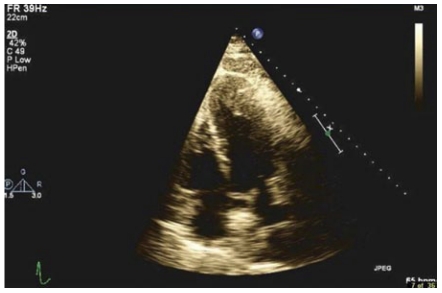

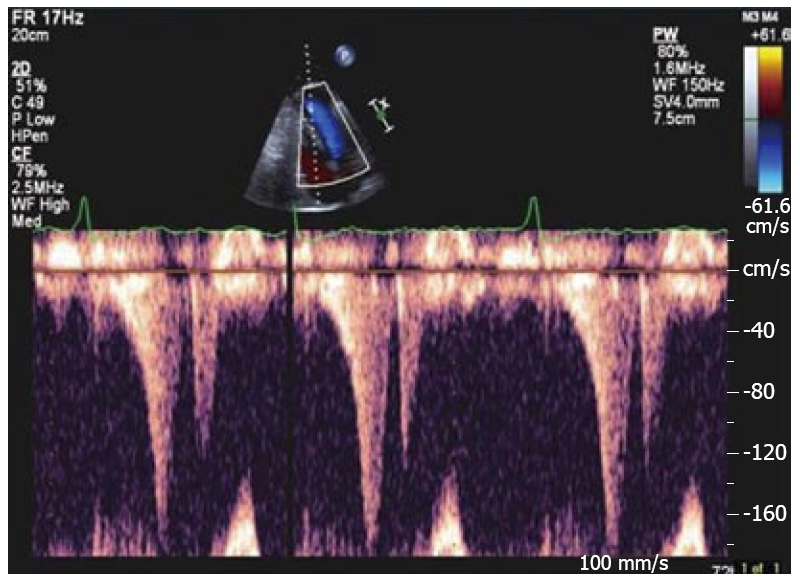

A 57-year-old white male with a history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue was seen in March 2007 for preoperative evaluation. He had no complaints of chest pain, dyspnea or palpitations. There was no family history of sudden death, congestive heart failure or cardiomyopathy. On examination his blood pressure was 125/72 mmHg, heart rate 67 bpm with no heart murmur or any signs of congestive heart failure. The rest of the examination was normal. He was evaluated again in 2008 for altered mental status. His physical examination was unremarkable. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy and inverted T-waves in V2 to V6 leads (Figure 1). All previous ECGs revealed similar findings. The cardiac enzymes and chest X-ray were normal. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed apical hypertrophy with LV end diastolic diameter of 5.1 cm and normal systolic function (Figure 2). Doppler imaging showed a dagger-shaped late peaking systolic gradient, consistent with HCM (Figure 3). The ECG findings were attributed to AHCM. Since he was asymptomatic, no further investigations or particular treatment for this condition was carried out. One year later the patient developed episodes of atrial fibrillation and supraventricular tachycardia, for which he was treated with amiodarone. He had no other cardiovascular complications and was followed in the clinic, till he passed away in June 2009, due to widespread metastatic disease.

Figure 1.

A 12-lead electrocardiogram showing left ventricular hypertrophy and inverted T-waves in the V2, V3, V4, V5 and V6 leads.

Figure 2.

A 2D transthoracic echocardiogram showing left ventricular apical hypertrophy.

Figure 3.

Doppler imaging showing a late peaking systolic gradient.

DISCUSSION

AHCM is frequently sporadic; however, a few families have been reported with autosomal dominant inheritance[3]. A sarcoma gene mutation (E101K mutation in the alpha-cardiac actin gene) has been identified in these families. A family history is more common in patients with asymmetric septal hypertrophy than with AHCM. Morphologically AHCM is divided into 3 types: pure focal, pure diffuse and mixed, of which pure focal is most common[4]. However in clinical practice this sub-classification is not widely accepted and its clinical relevance is unknown. Others have divided AHCM into two groups, based on whether they had isolated asymmetric apical hypertrophy (pure AHCM) or had co-existent hypertrophy of the interventricular septum (mixed AHCM)[5]. The diagnostic criteria for AHCM included demonstration of asymmetric LV hypertrophy, confined predominantly to the LV apex, with an apical wall thickness ≥ 15 mm and a ratio of maximal apical to posterior wall thickness ≥ 1.5 mm, based on an echocardiogram or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[5].

The mean age of presentation of AHCM is 41.4 ± 14.5 years and is most commonly seen in males[5]. About 54% of patients with AHCM are symptomatic and the most common presenting symptom is chest pain, followed by palpitations, dyspnea and syncope[5]. AHCM may also manifest as morbid events such as atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, embolic events, ventricular fibrillation and congestive heart failure[5]. Other complications of AHCM include apical aneurysm and cardiac arrest. Physical findings of an audible/palpable fourth heart sound and a new murmur are common[5]. Our patient was asymptomatic, with no family history and had no physical findings.

The most frequent ECG findings are negative T-waves in the precordial leads which are found in 93% of patients, followed by LV hypertrophy in 65% of patients[5]. Negative T-waves with a depth > 10 mm are found in 47% of patients with AHCM[5]. The ECG in our patient showed LV hypertrophy and negative T-waves with a maximum depth of 7 mm. TTE shows hypertrophy of the LV apex and is the initial diagnostic tool for AHCM. When the baseline images are suboptimal, a contrast echocardiogram is useful in establishing the diagnosis[6]. On contrast ventriculography AHCM shows a distinctive LV “spade-like” configuration[5]. On single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) myocardial perfusion imaging findings of resting “solar polar” map pattern and reduced flow reserve of the apex are the characteristics of AHCM[7]. Multislice spiral computed tomography can also be used to diagnose AHCM; besides diagnosis it provides information on cardiac anatomy, function and coronary arteries[8]. Cardiac MRI is also a valuable tool for diagnosing patients with inconclusive echocardiography and SPECT findings[9]. Although the initial diagnostic test for AHCM is most commonly TTE, the best diagnostic tool is considered to be cardiac MRI.

AHCM may mimic other conditions, including apical cardiac tumors[10], LV apical thrombus[11], isolated ventricular non-compaction[12], endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF)[13] and coronary artery disease[14] (Table 1). Chest pain in a patient with AHCM can be mistaken for ischemia from coronary artery disease[14]. Frequently these patients undergo a nuclear scan for abnormal ECG[15]. The majority of the patients with AHCM who suffer myocardial infarction have an apical infarct, and in these patients wall motion abnormalities varies from apical aneurysm to apical hyopokinesis[5]. Some patients may have asymptomatic apical infarction[5]. Hence, in clinical practice, an apical aneurysm may sometimes be seen with AHCM in asymptomatic patients.

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

| Disease | Diagnostic tool to establish diagnosis of AHCM |

| Coronary artery disease | Echocardiogram/coronary angiogram and LVG |

| Left ventricular apical tumors | Echocardiogram with contrast/CCT/CMRI |

| Left ventricular apical thrombus | Echocardiogram with contrast/CCT/CMRI |

| Isolated ventricular non-compaction | CMRI/CCT |

| Endomyocardial fibrosis | LVG/CMRI |

AHCM: Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; CMRI: Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; LVG: Left ventriculography; CCT: Cardiac computed tomography.

Isolated ventricular non-compaction may be differentiated from AHCM by high resolution images of the heart obtained by cardiac MRI[12]. An echocardiogram with contrast can be used to differentiate AHCM from a LV apical mass (thrombus or tumor)[11]. A LV angiogram shows apical obliteration during both systole and diastole in EMF, whereas in AHCM apical obliteration occurs only in systole and also there is an absence of significant ventricular hypertrophy in EMF patients[13].

In symptomatic patients with AHCM, verapamil, beta-blockers and antiarrhythmic agents are used[5]. Verapamil and beta-blockers are found to be beneficial in improving the symptoms in AHCM patients[16,17]. Amiodarone and procainamide are used in the treatment of atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias[18]. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) is recommended for high risk HCM patients with (1) previous cardiac arrest or sustained episodes of ventricular tachycardia; (2) syncope; (3) a family history of sudden death; or (4) episodes of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on serial Holter monitoring[19]. ICD has been was used in AHCM patients with cardiac arrest and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia[17].

Unlike other variants of HCM, the prognosis of AHCM is relatively benign. The overall mortality rate of AHCM patients was 10.5% and cardiovascular mortality was 1.9% after a follow-up of 13.6 ± 8.3 years[5]. Sudden death and cardiovascular events occur more commonly in patients with asymmetric septal hypertrophy than in those with AHCM[20]. A large LV end diastolic dimension may predict cardiac events in AHCM patients[21]. Some AHCM patients may develop sudden life-threatening complications, hence close follow-up of these patients is recommended[5].

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Stefan E Hardt, MD, Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Pulmology, University of Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 410, Heidelberg 69120, Germany; Dariusch Haghi, MD, I. Medizinische Klinik, Universitätsmedizin Mannheim, Theodor-Kutzer-Ufer 1-3, 68167 Mannheim, Germany

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Albanesi Filho FM, Castier MB, Lopes AS, Ginefra P. Is the apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy seen in one population in Rio de Janeiro city similar to that found in the East? Arq Bras Cardiol. 1997;69:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitaoka H, Doi Y, Casey SA, Hitomi N, Furuno T, Maron BJ. Comparison of prevalence of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Japan and the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1183–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arad M, Penas-Lado M, Monserrat L, Maron BJ, Sherrid M, Ho CY, Barr S, Karim A, Olson TM, Kamisago M, et al. Gene mutations in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112:2805–2811. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.547448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi EY, Rim SJ, Ha JW, Kim YJ, Lee SC, Kang DH, Park SW, Song JK, Sohn DW, Chung N. Phenotypic spectrum and clinical characteristics of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: multicenter echo-Doppler study. Cardiology. 2008;110:53–61. doi: 10.1159/000109407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, Rakowski P, Parker TG, Wigle ED, Rakowski H. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:638–645. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01778-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel J, Michaels J, Mieres J, Kort S, Mangion JR. Echocardiographic diagnosis of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with optison contrast. Echocardiography. 2002;19:521–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2002.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward RP, Pokharna HK, Lang RM, Williams KA. Resting "Solar Polar" map pattern and reduced apical flow reserve: characteristics of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy on SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2003;10:506–512. doi: 10.1016/s1071-3581(03)00455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou XH, Peng ZP, Peng Q, Li XM, Li ZP, Meng QF, Chen X. Clinical application of 64-slice spiral CT for apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Chin J of Radiol. 2008;42:911–915. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alpendurada F, Prasad SK. The missing spade: apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy investigation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;24:687–689. doi: 10.1007/s10554-008-9335-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veinot JP, O'Murchu B, Tazelaar HD, Orszulak TA, Seward JB. Cardiac fibroma mimicking apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a case report and differential diagnosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;9:94–99. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(96)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thanigaraj S, Pérez JE. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: echocardiographic diagnosis with the use of intravenous contrast image enhancement. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2000;13:146–149. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(00)90026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spirito P, Autore C. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or left ventricular non-compaction? A difficult differential diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1923–1924. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassan WM, Fawzy ME, Al Helaly S, Hegazy H, Malik S. Pitfalls in diagnosis and clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic findings in endomyocardial fibrosis: a 25-year experience. Chest. 2005;128:3985–3992. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duygu H, Zoghi M, Nalbantgil S, Ozerkan F, Akilli A, Akin M, Onder R, Erturk U. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy might lead to misdiagnosis of ischaemic heart disease. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;24:675–681. doi: 10.1007/s10554-008-9311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cianciulli TF, Saccheri MC, Masoli OH, Redruello MF, Lax JA, Morita LA, Gagliardi JA, Dorelle AN, Prezioso HA, Vidal LA. Myocardial perfusion SPECT in the diagnosis of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009;16:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s12350-008-9045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen SC, Wang KT, Hou CJY, Chou YS, Tsai CH. Apical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy with Severe Myocardial Bridging in a Syncopal Patient. Acta Cardiologica Sinica. 2003;19:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridjab D, Koch M, Zabel M, Schultheiss HP, Morguet AJ. Cardiac arrest and ventricular tachycardia in Japanese-type apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiology. 2007;107:81–86. doi: 10.1159/000094147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okishige K, Sasano T, Yano K, Azegami K, Suzuki K, Itoh K. Serious arrhythmias in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Intern Med. 2001;40:396–402. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maron BJ. Risk stratification and prevention of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiol Rev. 2002;10:173–181. doi: 10.1097/00045415-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang HS, Song JK, Song JM, Kang DH, Lee CW, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Park SW, Park SJ. Comparison of the clinical features of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy versus asymmetric septal hypertrophy in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2005;20:111–115. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2005.20.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suganuma Y, Shinmura K, Hasegawa H, Tani M, Nakamura Y. Clinical characteristics and cardiac events in elderly patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 1997;34:474–481. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.34.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]