Abstract

Myelin, a dielectric sheath that wraps large axons in the central and peripheral nervous systems, is essential for proper conductance of axon potentials. In multiple sclerosis (MS), autoimmune-mediated damage to myelin within the central nervous system (CNS) leads to progressive disability primarily due to limited endogenous repair of demyelination with associated axonal pathology. While treatments are available to limit demyelination, no treatments are available to promote myelin repair. Studies examining the molecular mechanisms that promote remyelination are therefore essential for identifying therapeutic targets to promote myelin repair and thereby limit disability in MS. Here, we present our current understanding of the critical extracellular and intracellular pathways that regulate the remyelinating capabilities of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) within the adult CNS.

Keywords: Cytokines, Chemokines, Growth Factors, MicroRNA, Multiple Sclerosis, Transcription Factors

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is characterized by progressive clinical decline due to axonal loss from chronic demyelination [1]. Although for many patients early disease is characterized by remyelination and recovery of function, eventually remyelination becomes limited and ultimately fails, for unclear reasons, leading to worsening disability [2]. Indeed, acutely injured axons may be found within demyelinated and actively demyelinating lesions, suggesting an intimate association between the mechanisms leading to myelin and axonal injury [3]. As oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) can be detected in MS lesions, it would seem that the endogenous repair mechanisms that normally respond to myelin damage become defective throughout the course of disease. Thus, there is great interest in understanding these mechanisms in order to identify reasons for failure and to develop therapies that promote the proliferation, migration and/or differentiation of OPCs in areas where demyelinated axons are at risk for further damage. Animal studies examining remyelination utilize a variety of approaches, which each highlight essential aspects of OPC biology. Thus, in murine models white matter damage is caused by induction of myelin-reactive immune cells via immunization or infection with mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), the latter of which leads to an acute encephalitis followed by a chronic demyelinating phase due to viral persistence within oligodendrocytes, or via use of ingestible or injectable toxins, such as cuprizone or lysolecthin, respectively, which induce apoptosis specifically in oligodendrocytes [4–5]. Findings in these models have been difficult to validate in MS patients primarily because human studies of demyelinated lesions are generally limited to analyses of postmortem tissue in patients with longstanding, progressive disease [2]. Many of these samples do not exhibit the dynamic OPC behaviors observed in animal models due to the physical and chemical barrier presented by astrogliosis. In this review, we will briefly outline the molecular pathways involved in regulation of remyelination that have been identified using animal experimentation and, where data are available, in validative studies performed using human tissues. The studies published so far provide hope that as critical myelin repair mechanisms are unraveled in the adult brain, there will be demonstrable targets for the correction of these processes in MS.

Oligodendrocyte differentiation during remyelination

Remyelination is the regeneration of an axon’s myelin sheath that has been damaged in many diseases such as MS. In general, the cellular mechanisms that mediate remyelination are a recapitulation of processes that occur during development. However, certain extracellular signaling molecules, such as chemokines, appear to function similarly during developmental myelination and remyelination. In the postnatal and adult brain, oligodendrocyte lineage cells migrate from the subventricular zone (SVZ) to the developing white matter where they stop proliferating, differentiate and myelinate axons [6–8]. Similar events have been shown to occur during remyelinating phases in mouse models of demyelination [5; 9–11]. For example, in both the lysolecithin-induced focal demyelination model, where toxin in directly injected into white matter areas, and in the cuprizone intoxication model, in which ingestion of copper chelator leads to complete demyelination of the corpus callosum, chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan positive (NG2+) cells are recruited to areas of demyelination from the subventricular zone (SVZ) [5; 12–13]. These cells differentiate and become oligodendrocytes that express myelin proteins in a sequential manner such that proteolipid protein (PLP), myelin basic protein (MBP) and 2′, 3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (CNPase) are expressed within five days of toxin cessation, whereas myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) is not expressed until 8 weeks after the initiation of remyelination [5; 9; 14]. Thus, the mechanisms that mediate remyelination are tightly regulated, orchestrating a specific sequence of events. A variety of proteins have been found to impact on remyelination including cytokines [15–16], chemokines [9; 11; 17–20], signaling molecules, [21–24], growth factors [5; 12; 25], transcription factors [26–28] and microRNA [29–32]. However, the specific role of each of these proteins during remyelination is unknown and simply inhibiting or augmenting expression of any one of these molecules may not be sufficient to promote remyelination in humans. Instead a comprehensive understanding of the functions of these molecules is necessary to devise effective treatment strategies for remyelination failure in MS.

Cytokines

Cytokines mediate inflammatory responses that promote pathogen clearance and prevent excessive tissue damage [33]. However, overproduction of cytokines may lead to excessive inflammation and cell death, as has been observed in peripheral autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease [34–36]. While successful targeting of cytokine production has led to effective treatments for some of these conditions [34–36], in the CNS certain cytokines exhibit critical roles in repair mechanisms. Thus, understanding downstream effects of cytokine signaling pathways in the CNS is essential for creating MS treatments that both prevent damage and promote repair.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, a pleiotropic cytokine that signals through TNFR1 and TNFR2, activates two different pathways: one that leads to apoptosis via death domain mediated caspase activation (TNFR1) and another that activates survival and protective pathways via nuclear factor kappa β (NFκβ) (TNFR1 and TNFR2) [37–38]. As TNFR1 binds the soluble form of TNF-α while TNFR2 binds the membrane bound form, the downstream effects of TNF-α signaling depend on the proximity of cellular sources of both ligand and receptor. Compared to unaffected individuals, MS patients exhibit high levels of TNF-α in both the cerebrospinal fluid and serum, which are positively correlated to severity of lesions [39–41]. In mice with experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) induced by immunization with myelin peptides, overexpression of TNF-α worsens demyelinating disease and administration of anti-TNF-α neutralizing antibodies or receptor fusion proteins is protective [42–47]. Despite these findings, clinical trials with, lenercept, a TNFR1 receptor extracellular domain fused to human IgG1 heavy chain, resulted in increased frequency, duration, and severity of MS exacerbations [48], suggesting alternative roles for TNF-α and/or its receptors that may depend on the disease stage. Studies using mice with targeted deletions of TNF-α or its receptors demonstrate that TNF-α mediates remyelination via TNFR2 signaling. Administration of cuprizone to TNF-α and TNFR2 knockout mice led to a significant delay in remyelination compared with wildtype control mice [15]. The attenuation in remyelination correlated with a reduction in the pool of proliferating oligodendrocyte progenitors and reduced mature oligodendrocytes. Analysis of mice lacking TNFR1 or TNFR2 indicated that TNFR2 is necessary for oligodendrocyte maturation [35]. These data suggests that TNF-α plays a role in CNS repair of myelin and explain the failure of anti-TNF agents to alleviate disease in MS patients.

Interleukin (IL)-1β is a proinflammatory cytokine associated with the pathology of demyelinating disorders such as MS and viral infections of the CNS and is induced during demyelination in animal models [16; 49–50]. Although IL-1β exerts cytotoxic effects on mature oligodendrocytes in vitro [51–52], IL-1β knockout mice do not exhibit differences in the severity of demyelination, the depletion of mature oligodendrocytes or the accumulation of oligodendrocyte progenitors within demyelinating lesions compared to wild-type mice during cuprizone-induced demyelination [16]. However, IL-1β knockout mice fail to adequately remyelinate due to lack of IL-1β–mediated expression of insulin growth factor (IGF)-1 [16; 53]. The expression of IGF-1 message and protein parallels the accumulation and differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitors within the lesion, which the IL-1β knockout mice do not exhibit [16; 53]. Similar to TNFα, IL-1β has been associated with exacerbating CNS pathology [49; 54]. Conversely, it aids in repair by inducing growth factor production to promote mature oligodendrocyte differentiation and remyelination during a pathological insult within the CNS

Chemokines and MS

Chemokines induce directed chemotaxis in nearby responsive cells, which is necessary to guide immune cells to sites of infection or injury. Many chemokines including CXCL12 and CXCL1 are induced during CNS development and direct the migration and maturation of neural precursor cells [55–57], suggesting that these molecules could mediate migration and differentiation during repair of CNS. Because remyelination failure may be due to either the lack of differentiating signals or the presence of inhibitory signals for OPCs, chemokine neurobiology has become an important area of investigation in studies of remyelination.

CXCL12 (formerly called stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1) is a potent leukocyte chemoattractant that controls B-cell lymphopoiesis and hematopoietic stem cell homing to bone marrow via signaling through G-protein-coupled receptor CXCR4 [58]. CXCR4 signaling is conserved in vertebrates, as it controls primordial germ and sensory cell migration in zebrafish [59]. Another CXCL12 receptor is the newly discovered receptor, CXCR7 that primarily acts to regulate CXCR4 activation via sequestration of CXCL12 [60]. Although studies of CXCR7 in the developing brain are limited, there have been some reports that OPCs may express CXCR7 [61]. Freshly isolated neonatal OPCs specifically respond to CXCL12 by directed chemotaxis, however, their maturation into oligodendrocytes is associated with increased and decreased expression of CXCR7 and CXCR4, respectively [61–63]. Indeed, studies using in vivo demyelinating models support the notion that CXCR4 plays an early role in the migration and differentiation of OPCs. In elegant studies by Carbajal et al., (2010), GFP+ neural stem cells (NSCs) introduced into the spinal cords of mice with chronic demyelination due to infection with MHV strain JHMV resulted in their migration, proliferation, and differentiation into mature oligodendrocytes [11]. Administration of anti-CXCL12 neutralizing antibodies or a small molecule inhibitor of CXCR4, but not CXCR7, resulted in a marked attenuation in both the migration and proliferation of the engrafted stem cells. Using the cuprizone model of remyelination, Patel et al., (2010) showed that CXCL12 specifically mediates OPC differentiation into mature, myelinating oligodendrocytes within the corpus callosum [9]. In these studies, antagonism of CXCR4 via pharmalogical blockade or in vivo RNA silencing led to arrest of OPC maturation, preventing expression of myelin proteins [9]. Taken altogether, these data suggest roles for CXCL12 and CXCR4 in the recruitment, proliferation and differentiation of OPCs during remyelination of the adult CNS.

Studies of human CNS tissues indicate that CXCL12 is expressed by endothelial cells and astrocytes (EC) within normal brain and is increased in these and other cells in a variety of diseases including neuroAIDS, stroke and MS [64–67]. Thus, analysis of active MS lesions, which exhibit some amount of remyelination, exhibit increased CXCL12 expression in astrocytes throughout lesion areas and in macrophages within vessels and perivascular cuffs, with low levels of staining on ECs [66]. In chronic MS lesions, however, less CXCL12 was observed with staining detected only within hypertrophic astrocytes near the lesion edge, suggesting a mechanism for loss of remyelination [64]. Because CXCL12 is required to recruit CXCR4+ OPCs for remyelination, but also restricts the entry of CXCR4+ immune cells at EC barriers [66; 68], therapies that promote CXCL12 expression may target both effects of CXCL12 signaling. Several studies suggest IL-1β and TNF-α may induce CXCL12 expression within endothelial cells and astrocytes [69–70] while interferon (IFN)-γ triggers decreased expression of the chemokine [71]. IFN-γ has also been shown to decrease EC expression of CXCR7, which controls levels of abluminal CXCL12 [71]. Thus, anti-cytokine biologicals are likely to impact on remyelination via both direct effects on cytokine signaling and indirect effects on patterns of chemokine expression.

CXCL1/CXCL2/CXCR2

CXCR2 plays a role in inflammation, oligodendroglial biology and myelin disorders [72]. Studies in mouse models of remyelination and of MS lesions demonstrate roles for CXCR2 and its ligands in both inflammation and repair. In active MS plaque lesions, CXCR2 is expressed by proliferating oligodendrocytes and reactive astrocytes, while its ligand, CXCL1, is expressed by activated astrocytes [20; 73], suggesting CXCL1 expression in astrocytes may recruit OPCs to the site of the lesion. However, other studies have shown that CXCR2 activation limits migration of OPCs [57]. In addition, CXCR2 expression has been detected on activated microglia at lesion borders, suggesting alternative functions for CXCR2 in response to injury [74]. Thus, CXCL1/CXCR2 may be involved in both the inflammatory component of MS and in OPC responses during remyelination.

Results in rodent models provide further support for the dual role of this chemokine and its receptor. Lui et al. (2010) detected CXCR2 expression on neutrophils, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), and oligodendrocytes in the CNS [18–19]. CXCR2-positive neutrophils contribute to demyelination in EAE and during cuprizone intoxication [18–19] and systemic injection of a small molecule inhibitor of CXCR2 at the onset of EAE decreased numbers of demyelinated lesions [19]. Bone marrow chimeric mice generated via transfer of CXCR2+/− bone marrow into nonlethally irradiated CXCR2+/+ and CXCR2−/− mice led to more proficient myelin repair in CXCR2−/− versus CXCR2+/+ recipients [19], suggesting that CXCR2 signaling inhibits repair when expressed by radiation insensitive neural cells. In vivo analysis showed that OPCs proliferated earlier in the demyelinated lesions of CXCR2−/− chimeric mice and in greater numbers than in tissues from CXCR2+/+ chimeric animals [18–19]. Demyelinated CNS slice cultures also demonstrated enhanced myelin repair when CXCR2 was blocked with either genetic deletion or neutralizing antibodies. These data suggest that loss of CXCR2 activity both attenuates demyelination and promotes OPC proliferation and differentiation. However, data in other contexts question whether this receptor may be used as a treatment target for demyelinating diseases.

CXCR2 signaling also protects oligodendrocytes and limits demyelination in murine models of virally-induced demyelination [17]. Demyelination induced by JHMV infection induced expression of the chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2 and their receptor CXCR2 within the spinal cord during the chronic infection phase [17]. CXCR2 antagonism with neutralizing antiserum in this setting delayed clinical recovery and resulted in increased numbers of apoptotic cells mainly within white matter tracts of the spinal cord [17]. Omari et al., (2009) also reported a protective role for CXCR2 during demyelination [75]. In transgenic mice during EAE, overexpression of CXCL1 in astrocytes led to a decrease in clinical severity, a decrease in demyelination and augmentation of remyelination [75]. Lane and colleagues suggest that the protective and pro-apoptotic roles of CXCR2 with regards to oligodendrocytes may be context dependent [17]. Therefore, further studies are necessary to fully determine the role of CXCR2 and its ligands during remyelination before therapeutic targets can be developed.

Toll-like Receptors

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) have well defined roles in innate immunity, but they also influence axonal pathfinding, dorsoventral patterning and hippocampal neurogenesis [76–77]. Recently, TLR-2 and its ligand, hyaluronan was detected in MS lesions and in normal appearing white matter [78–79]. OPC differentiation has been shown to be inhibited by several TLR2 agonists including hyaluronan [79]. These data suggest that TLR signaling could inhibit remyelination in MS and negatively impact on recovery during exacerbation. The development of therapies that inhibit TLR could therefore potentially alleviate failed remyelination in MS.

Growth Factors

Growth factors are defined as biologically active polypeptides that control growth and differentiation of responsive cells. Several of these growth factors were found to influence oligodendrocyte biology both in vitro and in animal models of remyelination. Growth factors have the potential to be a viable treatment option for MS. Transgenic mice overexpressing human epidermal growth factor receptor (hEGFR) exhibit increased lesion repopulation by OPCs with accelerated remyelination and functional recovery following focal demyelination of mouse corpus callosum compared to wild-type mice [5]. EGFR overexpression in SVZ and corpus callosum during early postnatal development also increased progenitor populations and promoted SVZ-to-lesion migration, enhancing oligodendrocyte generation and axonal myelination [5]. These data suggest that EGFR signaling during remyelination is similar to its role during development. EGF levels in the CSF of MS patients with relapsing-remitting or secondary progressive forms were significantly lower than those of nonclinical controls [80], suggesting that insufficient levels of EGF is associated with remyelination failure. Targeting EGF to enhance remyelination may hold promise for MS patients.

Several additional growth factors that are expressed during demyelination and implicated in remyelination include insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) [53; 81]. IGF-1 has both a protective and mitogenic role during de/remyelination in the cuprizone model. Thus, mice with targeted deletion of IGF-1 exhibit impairments in OPC proliferation and survival and inadequate remyelination after cuprizone-induced demyelination [53; 82–83]. In addition, in transgenic mice engineered to continuously express IGF-1, oligodendrocytes are protected from apoptosis during cuprizone intoxication [83]. Although a pilot study in which seven MS patients were given recombinant human IGF failed to show any significant differences, the drug was well tolerated [84]. Further studies are ongoing to determine the efficacy of IGF in promoting repair in patients with MS. PDGF and FGF are well-established trophic factors that promote the proliferation and differentiation of NSCs. In mice infected with MHV-A59 to induce focal demyelination of the spinal cord, PDGF and FGF were identified as mitogens regulating the proliferative responses of OPCs [81]. These studies demonstrate that growth factors have impact on all aspects of oligodendrocyte biology and remyelination.

Signaling Pathways

Many factors have been identified that orchestrate the differentiation and maturation of oligodendrocytes, but there are several intracellular signaling pathways that possibly mediate remyelination including, Notch-1, LINGO-1 (leucine rich repeat and Ig domain containing NOGO receptor interacting protein 1) and Wnt. Given the extensive recent reviews on Wnt signaling pathways [85–86], it will not be discussed in this review.

LINGO-1 is a protein that is abundantly expressed in the cortex of CNS and has been in implicated in the inhibition of axon regeneration [87]. It also regulates remyelination in the adult CNS by inhibiting oligodendrocyte differentiation. This process is a recapitulation of LINGO-1 function during developmental myelination [88]. Using 3 different animal models of de/remyelination: EAE, cuprizone induced demyelination, and lysophophatidylcholine (LPC) induced demyelination, Mi et al., (2009) demonstrated that LINGO-1 antagonism enhanced OPC differentiation and promoted remyelination of demyelinated axons [88]. Furthermore, LINGO-1 antagonism using monoclonal antibody 1A7 in the EAE model showed improvement in axonal integrity and the formation of new myelin sheath [89]. These data suggest that LINGO-1 antagonism has potential as a therapy for CNS repair of demyelinating disease. Recently, clinical trials have begun that will administer LINGO-1 antagonist BIIB033 to MS patients to determine CNS repair [90]. The efficacy of drug will be assessed via neurological examinations, MS performance scores, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

Notch-1 and its ligands are signaling molecules that are involved in gene regulation mechanisms including those that induce neuronal development [21; 91]. Nonmyelinating oligodendrocytes express Notch1 receptors, and neurons/axons express its ligand, Jagged1 or contactin [22; 92]. Binding of Jagged1 to Notch induces expression of the transcription factor Hes5, which blocks the maturation of Notch1-expressing cells, facilitating the migration of OPCs to white-matter tracts of the CNS [92–94]. As development proceeds, downregulation of Jagged1 is associated with the maturation of oligodendrocyte precursors and myelination [94]. In active MS lesions, Jagged1 was detected within reactive astrocytes, whereas Notch1 and Hes5 were found within oligodendrocytes [23]. In contrast, astrocytes in remyelinated areas did not show Jagged1 expression. In addition, outgrowth of processes of human oligodendrocyte cultures was blocked when cells were transfected with Jagged1 [23; 95]. These data suggest that notch-1 may inhibit differentiation of OPCs in order to facilitate their migration to the white matter.

microRNA

MicroRNA are small RNA molecules that function as posttranscriptional regulators of gene function either through translational inhibition or target RNA degradation [31]. These molecules have recently emerged as mediators of many biological functions including the proliferation and differentiation of NPCs [96] and several groups have demonstrated that microRNAs exert roles in remyelination. Junker et al., (2009) created microRNA profiles from active and inactive MS lesions via laser capture microdissection of single cells and showed dysregulation of transcripts such as CD47, which is expressed by apoptotic cells to prevent macrophage phagocytosis, specifically in active lesions [29]. The authors speculated that loss of microRNA-mediated reduction of CD47 could potentially release macrophages from inhibitory control, thereby promoting phagocytosis of myelin. This mechanism may have broad implications for miRNA-regulated macrophage activation in inflammatory diseases [29].

Several studies demonstrate that oligodendrocyte maturation may depend on microRNAs. Dugas et al (2010) showed that conditional deletion of Dicer1, a miRNA-processing enzyme, prevented OPC differentiation in vitro due to the lack of mature miRNAs. Furthermore, microRNA microarray analysis has identified two miRNAs, miRNA-219 and mi-338, necessary for oligodendrocyte differentiation. Inhibition of these specific miRNAs prevents transcription factor induction of OPC maturation [32]. The role of miRNAs in remyelination, however, is unclear as studies have yet to evaluate miRNAs in this context. Future studies will determine whether these small molecules also regulate remyelination.

Transcription Factors

Both myelination and remyelination occur through the activation of myelin protein genes that are induced by various transcription factors. The sequential activation of myelin protein correlates with both activation and inhibition of several transcription factors such as Olig1, Olig2 and Nkx2.2. Olig1 is a basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factor expressed by oligodendrocytes in the CNS [97]. This transcription factor is critical for developmental myelination and Olig1−/− mice have a shortened life span [98], resulting from a failure to induce myelin specific gene expression and arrested myelination. Recently, a critical role for Olig1 in repairing demyelinated lesions in the adult CNS has been demonstrated [97]. Olig1 translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in early remyelinating lesions in EAE as well as in oligodendrocyte precursor cells at the edge of MS lesions [97]. Another transcription factor know as SOX10 is part of the SOXE family of transcription factors, which are known to regulate oligodendrocyte fate [99]. SOX10 plays a major role in the promoting terminal oligodendrocyte differentiation and loss of SOX10 activity leads to disruption of oligodendrocyte differentiation [100]. Recent data has shown that Olig1 and SOX10 can complex together to synergistically activate MBP gene transcription [101]. Several transcription factors, such as Mash1 and Tcf4, have been used to identify cells withn the oligodendrocyte lineage but are additionally expressed by multipotent progenitor cells within neurogenic zones [102–103]. Tcf4 has also been demonstrated to function in catenin-dependent Wnt signaling [104].

Olig2 and Nkx2.2 are transcription factors expressed by OPCs and mature oligodendrocytes. Recent studies have revealed the importance of Olig2 for the differentiation of neural progenitor cells into the oligodendroglial lineage [27; 105], while Nkx2.2 regulates the maturation and differentiation of oligodendroglial progenitors [28]. Overexpression of Olig2 induces differentiation of neural stem cells into mature oligodendrocytes in vitro [106] and disruption of Olig2 in vivo leads to a lack of NG2+ OPCs and decreased numbers of oligodendrocytes in the spinal cord [27; 107]. In contrast, loss of Nkx2.2 results in increased numbers of OPCs [28]. Strong Olig2 or Nkx2.2 signals were observed in OPCs in the spinal cord of adult mice, while mature oligodendrocytes expressed low levels of these two transcription factors suggesting that a specific pattern of transcription factor coexpression correlates with the stage of OPC/oligodendrocyte maturation [26]. As transcription factors and the myelin genes they induce are the final targets of many of the molecules discussed in this review, direct targeting of myelin gene expression as a method to treat remyelination failure in MS may prove to be the most powerful approach.

Concluding Remarks

Although studies demonstrate that the CNS is capable of responding to myelin damage by triggering developmental mechanisms that induce remyelination, it is unclear why endogenous repair mechanisms ultimately fail in patients with MS. Given that OPCs and premyelinating oligodendrocytes may be detected in acute MS lesions [108], it would seem that remyelination is likely hindered by a block in differentiation pathways. Molecules that interfere with remyelination may be derived from infiltrating immune cells or activated glia, as discussed above [18; 109]. Of interest, chronically demyelinated lesions are frequently observed to contain few OPCs and mostly activated astrocytes [108; 110], suggesting that astrogliosis prevents OPC differentiation or that OPCs that fail to differentiate along the oligodendrocyte lineage induce astrogliosis or, somehow, become astrocytes themselves [111]. It is also possible that the repair mechanisms triggered by CNS damage during MS not only contribute to chronic leukocyte infiltration but also induce neuronal injury responses that prevent remyelination. Future studies will ultimately identify these context-specific molecules that impact on neural precursor cell differentiation.

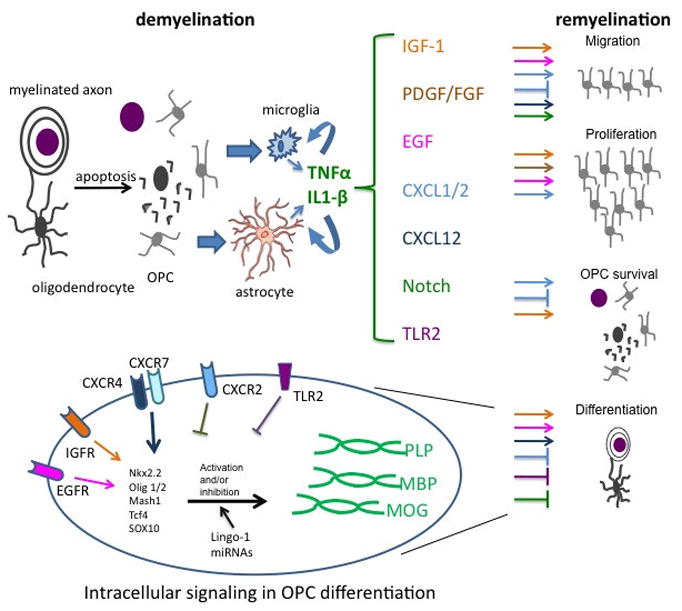

Figure 1. Putative Remyelination Mechanisms.

Depicted are roles for cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, transcription factors and other signaling proteins in remyelination of demyelinated lesions in MS. During demyelination, oligodendrocytes undergo apopotosis, leaving debris, which may contribute to the activation of microglia and astrocytes, which then express cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) [15–16]. Cytokines alter expression of chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL12) and growth factors (IGF-1, PDGF, FGF, EGF), whose activation or inhibition of various aspects of remyelination are depicted via color-coding of arrows and signs of blockade, respectively, for each biologic process (migration, proliferation, OPC survival and differentiation). For certain molecules, such as CXCL1/2, opposing effects on OPCs have been observed, depending on the animal model used. Growth factors differentially impact on cell survival and proliferation while chemokines contribute to migration and differentiation, depending on OPC position. TLR2 activation inhibits OPC differentiation [79]. Notch-1 also blocks OPC differentiation to promote migration. Molecules that regulate OPC maturation are depicted in the context of intracellular signaling during differentiation. Included are chemokine (CXCR4/7, CXCR2) and growth factor (IGF-1R, EGFR) receptors, miRNAs, Lingo-1 and several transcription factors (Nkx2.2, Olig1/2, Mash1, Tcf4, SOX10) which may negatively or positively impact on the expression of myelin proteins including proteolipid protein (PLP), myelin basic protein (MBP) and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG).

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant NS059560 and by grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (all to R.S.K).

Abbreviations

- CNS

central nervous system

- CNPase

2′, 3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- EC

endothelial cells

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1 beta

- OPC

oligodendrocyte precursor cell

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PLP

proteolipid protein

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- MHV

mouse hepatitis virus

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- SVZ

subventricular zone

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TLR

Toll-like receptors

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References Cited

- 1.Irvine KA, Blakemore WF. Remyelination protects axons from demyelination-associated axon degeneration. Brain. 2008;131:1464–1477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin RJ. Why does remyelination fail in multiple sclerosis? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:705–714. doi: 10.1038/nrn917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Stefano N, Matthews PM, Fu L, Narayanan S, Stanley J, Francis GS, Antel JP, Arnold DL. Axonal damage correlates with disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Results of a longitudinal magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 8):1469–1477. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.8.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsushima GK, Morell P. The neurotoxicant, cuprizone, as a model to study demyelination and remyelination in the central nervous system. Brain Pathol. 2001;11:107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguirre A, Dupree JL, Mangin JM, Gallo V. A functional role for EGFR signaling in myelination and remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:990–1002. doi: 10.1038/nn1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumann N, Pham-Dinh D. Biology of oligodendrocyte and myelin in the mammalian central nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:871–927. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine JM, Reynolds R, Fawcett JW. The oligodendrocyte precursor cell in health and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01691-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menn B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Yaschine C, Gonzalez-Perez O, Rowitch D, Alvarez-Buylla A. Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7907–7918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel JR, McCandless EE, Dorsey D, Klein RS. CXCR4 promotes differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitors and remyelination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11062–11067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006301107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nait-Oumesmar B, Picard-Riera N, Kerninon C, Baron-Van Evercooren A. The role of SVZ-derived neural precursors in demyelinating diseases: from animal models to multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2008;265:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carbajal KS, Schaumburg C, Strieter R, Kane J, Lane TE. Migration of engrafted neural stem cells is mediated by CXCL12 signaling through CXCR4 in a viral model of multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11068–11073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006375107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguirre A, Gallo V. Reduced EGFR signaling in progenitor cells of the adult subventricular zone attenuates oligodendrogenesis after demyelination. Neuron Glia Biol. 2007;3:209–220. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X08000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nait-Oumesmar B, Decker L, Lachapelle F, Avellana-Adalid V, Bachelin C, Van Evercooren AB. Progenitor cells of the adult mouse subventricular zone proliferate, migrate and differentiate into oligodendrocytes after demyelination. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4357–4366. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindner M, Heine S, Haastert K, Garde N, Fokuhl J, Linsmeier F, Grothe C, Baumgartner W, Stangel M. Sequential myelin protein expression during remyelination reveals fast and efficient repair after central nervous system demyelination. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34:105–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnett HA, Mason J, Marino M, Suzuki K, Matsushima GK, Ting JP. TNF alpha promotes proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitors and remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/nn738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason JL, Suzuki K, Chaplin DD, Matsushima GK. Interleukin-1beta promotes repair of the CNS. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7046–7052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07046.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosking MP, Tirotta E, Ransohoff RM, Lane TE. CXCR2 signaling protects oligodendrocytes and restricts demyelination in a mouse model of viral-induced demyelination. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu L, Belkadi A, Darnall L, Hu T, Drescher C, Cotleur AC, Padovani-Claudio D, He T, Choi K, Lane TE, Miller RH, Ransohoff RM. CXCR2-positive neutrophils are essential for cuprizone-induced demyelination: relevance to multiple sclerosis. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:319–326. doi: 10.1038/nn.2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu L, Darnall L, Hu T, Choi K, Lane TE, Ransohoff RM. Myelin repair is accelerated by inactivating CXCR2 on nonhematopoietic cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9074–9083. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1238-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omari KM, John G, Lango R, Raine CS. Role for CXCR2 and CXCL1 on glia in multiple sclerosis. Glia. 2006;53:24–31. doi: 10.1002/glia.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aguirre A, Rubio ME, Gallo V. Notch and EGFR pathway interaction regulates neural stem cell number and self-renewal. Nature. 2010;467:323–327. doi: 10.1038/nature09347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakahara J, Kanekura K, Nawa M, Aiso S, Suzuki N. Abnormal expression of TIP30 and arrested nucleocytoplasmic transport within oligodendrocyte precursor cells in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:169–181. doi: 10.1172/JCI35440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.John GR, Shankar SL, Shafit-Zagardo B, Massimi A, Lee SC, Raine CS, Brosnan CF. Multiple sclerosis: re-expression of a developmental pathway that restricts oligodendrocyte maturation. Nat Med. 2002;8:1115–1121. doi: 10.1038/nm781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brosnan CF, Selmaj K, Raine CS. Hypothesis: a role for tumor necrosis factor in immune-mediated demyelination and its relevance to multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 1988;18:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(88)90137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murtie JC, Zhou YX, Le TQ, Vana AC, Armstrong RC. PDGF and FGF2 pathways regulate distinct oligodendrocyte lineage responses in experimental demyelination with spontaneous remyelination. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitada M, Rowitch DH. Transcription factor co-expression patterns indicate heterogeneity of oligodendroglial subpopulations in adult spinal cord. Glia. 2006;54:35–46. doi: 10.1002/glia.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ligon KL, Fancy SP, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Olig gene function in CNS development and disease. Glia. 2006;54:1–10. doi: 10.1002/glia.20273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi Y, Cai J, Wu Y, Wu R, Lee J, Fu H, Rao M, Sussel L, Rubenstein J, Qiu M. Control of oligodendrocyte differentiation by the Nkx2.2 homeodomain transcription factor. Development. 2001;128:2723–2733. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Junker A, Krumbholz M, Eisele S, Mohan H, Augstein F, Bittner R, Lassmann H, Wekerle H, Hohlfeld R, Meinl E. MicroRNA profiling of multiple sclerosis lesions identifies modulators of the regulatory protein CD47. Brain. 2009;132:3342–3352. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nave KA. Oligodendrocytes and the “micro brake” of progenitor cell proliferation. Neuron. 2010;65:577–579. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao X, He X, Han X, Yu Y, Ye F, Chen Y, Hoang T, Xu X, Mi QS, Xin M, Wang F, Appel B, Lu QR. MicroRNA-mediated control of oligodendrocyte differentiation. Neuron. 2010;65:612–626. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dugas JC, Cuellar TL, Scholze A, Ason B, Ibrahim A, Emery B, Zamanian JL, Foo LC, McManus MT, Barres BA. Dicer1 and miR-219 Are required for normal oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Neuron. 2010;65:597–611. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banyer JL, Hamilton NH, Ramshaw IA, Ramsay AJ. Cytokines in innate and adaptive immunity. Rev Immunogenet. 2000;2:359–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin J, Chang Y, Wei W. Clinical application and evaluation of anti-TNF-alpha agents for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:1133–1140. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kircik LH, Del Rosso JQ. Anti-TNF agents for the treatment of psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:546–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikolaus S, Schreiber S. [Anti-TNF biologics in the treatment of chronic inflammatory bowel disease] Internist (Berl) 2008;49:947–948. 950–943. doi: 10.1007/s00108-008-2058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Micheau O, Tschopp J. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell. 2003;114:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnhart BC, Peter ME. The TNF receptor 1: a split personality complex. Cell. 2003;114:148–150. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck J, Rondot P, Catinot L, Falcoff E, Kirchner H, Wietzerbin J. Increased production of interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor precedes clinical manifestation in multiple sclerosis: do cytokines trigger off exacerbations? Acta Neurol Scand. 1988;78:318–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1988.tb03663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maimone D, Gregory S, Arnason BG, Reder AT. Cytokine levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and serum of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 1991;32:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(91)90073-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharief MK, Hentges R. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha and disease progression in patients with multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:467–472. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gimenez MA, Sim J, Archambault AS, Klein RS, Russell JH. A tumor necrosis factor receptor 1-dependent conversation between central nervous system-specific T cells and the central nervous system is required for inflammatory infiltration of the spinal cord. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1200–1209. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Probert L, Plows D, Kontogeorgos G, Kollias G. The type I interleukin-1 receptor acts in series with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) to induce arthritis in TNF-transgenic mice. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1794–1797. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruddle NH, Bergman CM, McGrath KM, Lingenheld EG, Grunnet ML, Padula SJ, Clark RB. An antibody to lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor prevents transfer of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1193–1200. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selmaj K, Papierz W, Glabinski A, Kohno T. Prevention of chronic relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;56:135–141. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)00139-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selmaj K, Raine CS, Cross AH. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy abrogates autoimmune demyelination. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:694–700. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Selmaj KW, Raine CS. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: immunotherapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors. Neurology. 1995;45:S44–49. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6_suppl_6.s44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.TNF neutralization in MS: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study. The Lenercept Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and The University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group. Neurology. 1999;53:457–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Jong BA, Huizinga TW, Bollen EL, Uitdehaag BM, Bosma GP, van Buchem MA, Remarque EJ, Burgmans AC, Kalkers NF, Polman CH, Westendorp RG. Production of IL-1beta and IL-1Ra as risk factors for susceptibility and progression of relapse-onset multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;126:172–179. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takikita S, Takano T, Narita T, Takikita M, Ohno M, Shimada M. Neuronal apoptosis mediated by IL-1 beta expression in viral encephalitis caused by a neuroadapted strain of the mumps virus (Kilham Strain) in hamsters. Exp Neurol. 2001;172:47–59. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Merrill JE. Effects of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha on astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes, and glial precursors in vitro. Dev Neurosci. 1991;13:130–137. doi: 10.1159/000112150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brogi A, Strazza M, Melli M, Costantino-Ceccarini E. Induction of intracellular ceramide by interleukin-1 beta in oligodendrocytes. J Cell Biochem. 1997;66:532–541. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19970915)66:4<532::aid-jcb12>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mason JL, Xuan S, Dragatsis I, Efstratiadis A, Goldman JE. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling through type 1 IGF receptor plays an important role in remyelination. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7710–7718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07710.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shaftel SS, Carlson TJ, Olschowka JA, Kyrkanides S, Matousek SB, O’Banion MK. Chronic interleukin-1beta expression in mouse brain leads to leukocyte infiltration and neutrophil-independent blood brain barrier permeability without overt neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9301–9309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1418-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stumm R, Kolodziej A, Schulz S, Kohtz JD, Hollt V. Patterns of SDF-1alpha and SDF-1gamma mRNAs, migration pathways, and phenotypes of CXCR4-expressing neurons in the developing rat telencephalon. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502:382–399. doi: 10.1002/cne.21336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stumm R, Hollt V. CXC chemokine receptor 4 regulates neuronal migration and axonal pathfinding in the developing nervous system: implications for neuronal regeneration in the adult brain. J Mol Endocrinol. 2007;38:377–382. doi: 10.1677/JME-06-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsai HH, Frost E, To V, Robinson S, Ffrench-Constant C, Geertman R, Ransohoff RM, Miller RH. The chemokine receptor CXCR2 controls positioning of oligodendrocyte precursors in developing spinal cord by arresting their migration. Cell. 2002;110:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nagasawa T. A chemokine, SDF-1/PBSF, and its receptor, CXC chemokine receptor 4, as mediators of hematopoiesis. Int J Hematol. 2000;72:408–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doitsidou M, Reichman-Fried M, Stebler J, Koprunner M, Dorries J, Meyer D, Esguerra CV, Leung T, Raz E. Guidance of primordial germ cell migration by the chemokine SDF-1. Cell. 2002;111:647–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valentin G, Haas P, Gilmour D. The chemokine SDF1a coordinates tissue migration through the spatially restricted activation of Cxcr7 and Cxcr4b. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gottle P, Kremer D, Jander S, Odemis V, Engele J, Hartung HP, Kury P. Activation of CXCR7 receptor promotes oligodendroglial cell maturation. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:915–924. doi: 10.1002/ana.22214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dziembowska M, Tham TN, Lau P, Vitry S, Lazarini F, Dubois-Dalcq M. A role for CXCR4 signaling in survival and migration of neural and oligodendrocyte precursors. Glia. 2005;50:258–269. doi: 10.1002/glia.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maysami S, Nguyen D, Zobel F, Pitz C, Heine S, Hopfner M, Stangel M. Modulation of rat oligodendrocyte precursor cells by the chemokine CXCL12. Neuroreport. 2006;17:1187–1190. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000227985.92551.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Calderon TM, Eugenin EA, Lopez L, Kumar SS, Hesselgesser J, Raine CS, Berman JW. A role for CXCL12 (SDF-1alpha) in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis: regulation of CXCL12 expression in astrocytes by soluble myelin basic protein. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;177:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hill WD, Hess DC, Martin-Studdard A, Carothers JJ, Zheng J, Hale D, Maeda M, Fagan SC, Carroll JE, Conway SJ. SDF-1 (CXCL12) is upregulated in the ischemic penumbra following stroke: association with bone marrow cell homing to injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:84–96. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCandless EE, Piccio L, Woerner BM, Schmidt RE, Rubin JB, Cross AH, Klein RS. Pathological expression of CXCL12 at the blood-brain barrier correlates with severity of multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:799–808. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang K, McQuibban GA, Silva C, Butler GS, Johnston JB, Holden J, Clark-Lewis I, Overall CM, Power C. HIV-induced metalloproteinase processing of the chemokine stromal cell derived factor-1 causes neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1064–1071. doi: 10.1038/nn1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCandless EE, Wang Q, Woerner BM, Harper JM, Klein RS. CXCL12 limits inflammation by localizing mononuclear infiltrates to the perivascular space during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:8053–8064. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCandless EE, Budde M, Lees JR, Dorsey D, Lyng E, Klein RS. IL-1R signaling within the central nervous system regulates CXCL12 expression at the blood-brain barrier and disease severity during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2009;183:613–620. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Han Y, He T, Huang DR, Pardo CA, Ransohoff RM. TNF-alpha mediates SDF-1 alpha-induced NF-kappa B activation and cytotoxic effects in primary astrocytes. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:425–435. doi: 10.1172/JCI12629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cruz-Orengo L, Holman DW, Dorsey D, Zhou L, Zhang P, Wright M, McCandless EE, Patel JR, Luker GD, Littman DR, Russell JH, Klein RS. CXCR7 influences leukocyte entry into the CNS parenchyma by controlling abluminal CXCL12 abundance during autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2011;208:327–339. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Charo IF, Ransohoff RM. The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:610–621. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Omari KM, John GR, Sealfon SC, Raine CS. CXC chemokine receptors on human oligodendrocytes: implications for multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2005;128:1003–1015. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Filipovic R, Jakovcevski I, Zecevic N. GRO-alpha and CXCR2 in the human fetal brain and multiple sclerosis lesions. Dev Neurosci. 2003;25:279–290. doi: 10.1159/000072275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Omari KM, Lutz SE, Santambrogio L, Lira SA, Raine CS. Neuroprotection and remyelination after autoimmune demyelination in mice that inducibly overexpress CXCL1. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:164–176. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pevsner-Fischer M, Morad V, Cohen-Sfady M, Rousso-Noori L, Zanin-Zhorov A, Cohen S, Cohen IR, Zipori D. Toll-like receptors and their ligands control mesenchymal stem cell functions. Blood. 2007;109:1422–1432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rolls A, Shechter R, London A, Ziv Y, Ronen A, Levy R, Schwartz M. Toll-like receptors modulate adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1081–1088. doi: 10.1038/ncb1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Back SA, Tuohy TM, Chen H, Wallingford N, Craig A, Struve J, Luo NL, Banine F, Liu Y, Chang A, Trapp BD, Bebo BF, Jr, Rao MS, Sherman LS. Hyaluronan accumulates in demyelinated lesions and inhibits oligodendrocyte progenitor maturation. Nat Med. 2005;11:966–972. doi: 10.1038/nm1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sloane JA, Batt C, Ma Y, Harris ZM, Trapp B, Vartanian T. Hyaluronan blocks oligodendrocyte progenitor maturation and remyelination through TLR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11555–11560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006496107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scalabrino G, Galimberti D, Mutti E, Scalabrini D, Veber D, De Riz M, Bamonti F, Capello E, Mancardi GL, Scarpini E. Loss of epidermal growth factor regulation by cobalamin in multiple sclerosis. Brain Res. 2010;1333:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frost EE, Nielsen JA, Le TQ, Armstrong RC. PDGF and FGF2 regulate oligodendrocyte progenitor responses to demyelination. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:457–472. doi: 10.1002/neu.10158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mason JL, Jones JJ, Taniike M, Morell P, Suzuki K, Matsushima GK. Mature oligodendrocyte apoptosis precedes IGF-1 production and oligodendrocyte progenitor accumulation and differentiation during demyelination/remyelination. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:251–262. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000801)61:3<251::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mason JL, Ye P, Suzuki K, D’Ercole AJ, Matsushima GK. Insulin-like growth factor-1 inhibits mature oligodendrocyte apoptosis during primary demyelination. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5703–5708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05703.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Frank JA, Richert N, Lewis B, Bash C, Howard T, Civil R, Stone R, Eaton J, McFarland H, Leist T. A pilot study of recombinant insulin-like growth factor-1 in seven multiple sderosis patients. Mult Scler. 2002;8:24–29. doi: 10.1191/1352458502ms768oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Emery B. Regulation of oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Science. 2010;330:779–782. doi: 10.1126/science.1190927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fancy SP, Kotter MR, Harrington EP, Huang JK, Zhao C, Rowitch DH, Franklin RJ. Overcoming remyelination failure in multiple sclerosis and other myelin disorders. Exp Neurol. 2010;225:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mi S, Lee X, Shao Z, Thill G, Ji B, Relton J, Levesque M, Allaire N, Perrin S, Sands B, Crowell T, Cate RL, McCoy JM, Pepinsky RB. LINGO-1 is a component of the Nogo-66 receptor/p75 signaling complex. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:221–228. doi: 10.1038/nn1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mi S, Miller RH, Tang W, Lee X, Hu B, Wu W, Zhang Y, Shields CB, Miklasz S, Shea D, Mason J, Franklin RJ, Ji B, Shao Z, Chedotal A, Bernard F, Roulois A, Xu J, Jung V, Pepinsky B. Promotion of central nervous system remyelination by induced differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:304–315. doi: 10.1002/ana.21581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mi S, Hu B, Hahm K, Luo Y, Kam Hui ES, Yuan Q, Wong WM, Wang L, Su H, Chu TH, Guo J, Zhang W, So KF, Pepinsky B, Shao Z, Graff C, Garber E, Jung V, Wu EX, Wu W. LINGO-1 antagonist promotes spinal cord remyelination and axonal integrity in MOG-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/nm1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.BiogenIdec. Safety Study of BIIB033 in Subjects with Multiple Sclerosis. 2010 http://ClinicalTrialsFeeds.org/clinical-trials/show/NCT01244139.

- 91.Gaiano N, Fishell G. The role of notch in promoting glial and neural stem cell fates. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:471–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.030702.130823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang S, Sdrulla AD, di Sibio G, Bush G, Nofziger D, Hicks C, Weinmaster G, Barres BA. Notch receptor activation inhibits oligodendrocyte differentiation. Neuron. 1998;21:63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kondo T, Raff M. Basic helix-loop-helix proteins and the timing of oligodendrocyte differentiation. Development. 2000;127:2989–2998. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ohtsuka T, Ishibashi M, Gradwohl G, Nakanishi S, Guillemot F, Kageyama R. Hes1 and Hes5 as notch effectors in mammalian neuronal differentiation. EMBO J. 1999;18:2196–2207. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brosnan CF, John GR. Revisiting Notch in remyelination of multiple sclerosis lesions. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:10–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI37786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stefani G, Slack FJ. Small non-coding RNAs in animal development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:219–230. doi: 10.1038/nrm2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Arnett HA, Fancy SP, Alberta JA, Zhao C, Plant SR, Kaing S, Raine CS, Rowitch DH, Franklin RJ, Stiles CD. bHLH transcription factor Olig1 is required to repair demyelinated lesions in the CNS. Science. 2004;306:2111–2115. doi: 10.1126/science.1103709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xin M, Yue T, Ma Z, Wu FF, Gow A, Lu QR. Myelinogenesis and axonal recognition by oligodendrocytes in brain are uncoupled in Olig1-null mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1354–1365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3034-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wegner M, Stolt CC. From stem cells to neurons and glia: a Soxist’s view of neural development. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stolt CC, Rehberg S, Ader M, Lommes P, Riethmacher D, Schachner M, Bartsch U, Wegner M. Terminal differentiation of myelin-forming oligodendrocytes depends on the transcription factor Sox10. Genes Dev. 2002;16:165–170. doi: 10.1101/gad.215802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li H, Lu Y, Smith HK, Richardson WD. Olig1 and Sox10 interact synergistically to drive myelin basic protein transcription in oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14375–14382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4456-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Flora A, Garcia JJ, Thaller C, Zoghbi HY. The E-protein Tcf4 interacts with Math1 to regulate differentiation of a specific subset of neuronal progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15382–15387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707456104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Aguirre AA, Chittajallu R, Belachew S, Gallo V. NG2-expressing cells in the subventricular zone are type C-like cells and contribute to interneuron generation in the postnatal hippocampus. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:575–589. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fancy SP, Baranzini SE, Zhao C, Yuk DI, Irvine KA, Kaing S, Sanai N, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Dysregulation of the Wnt pathway inhibits timely myelination and remyelination in the mammalian CNS. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1571–1585. doi: 10.1101/gad.1806309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ligon KL, Kesari S, Kitada M, Sun T, Arnett HA, Alberta JA, Anderson DJ, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. Development of NG2 neural progenitor cells requires Olig gene function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7853–7858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Copray S, Balasubramaniyan V, Levenga J, de Bruijn J, Liem R, Boddeke E. Olig2 overexpression induces the in vitro differentiation of neural stem cells into mature oligodendrocytes. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1001–1010. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lu QR, Sun T, Zhu Z, Ma N, Garcia M, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. Common developmental requirement for Olig function indicates a motor neuron/oligodendrocyte connection. Cell. 2002;109:75–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Snethen H, Love S, Scolding N. Disease-responsive neural precursor cells are present in multiple sclerosis lesions. Regen Med. 2008;3:835–847. doi: 10.2217/17460751.3.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Imai M, Watanabe M, Suyama K, Osada T, Sakai D, Kawada H, Matsumae M, Mochida J. Delayed accumulation of activated macrophages and inhibition of remyelination after spinal cord injury in an adult rodent model. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8:58–66. doi: 10.3171/SPI-08/01/058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wilson HC, Scolding NJ, Raine CS. Co-expression of PDGF alpha receptor and NG2 by oligodendrocyte precursors in human CNS and multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;176:162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hu JG, Wang YX, Zhou JS, Chen CJ, Wang FC, Li XW, Lu HZ. Differential Gene Expression in Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells, Oligodendrocytes and Type II Astrocytes. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2011;223:161–176. doi: 10.1620/tjem.223.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]