Abstract

Insulin/insulin-like growth factor type 1 signaling regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in worms, flies, and mammals. In a previous study, we revealed that insulin receptor (IR) mutant mice, which carry a homologous mutation found in the long-lived daf-2 mutant of Caenorhabditis elegans, showed enhanced resistance to oxidative stress cooperatively modulated by sex hormones and dietary signals (Baba et al., (2005)). We herein investigated the lifespan of IR mutant mice to evaluate the biological significance of insulin signaling in mice. Under normoxia, mutant male mice had a lifespan comparable to that of wild-type male mice. IR mutant female mice also showed a lifespan similar to that of wild-type female mice, in spite of the fact that the IR mutant female mice acquired more resistance to oxidative stress than IR mutant male mice. On the other hand, IR mutant male and female mice both showed insulin resistance with hyperinsulinemia, but they did not develop hyperglycemia throughout their entire lifespan. These data indicate that the IR mutation does not impact the lifespan in mice, thus suggesting that insulin signaling might have a limited effect on the lifespan of mice.

1. Introduction

Accumulating evidence indicates that insulin/insulin-like growth factor type 1 (IGF-1) signaling regulates lifespan in worms, flies, and mammals [1, 2]. In Caenorhabditis elegans, a mutation of the daf-2 gene that encodes an insulin/IGF-1 receptor ortholog significantly extended the lifespan and enhanced the resistance of the worms to oxidative stress [3, 4]. The lifespan extension caused by daf-2 mutations required the activity of daf-16 [3], which encodes a FOXO family transcription factor [5, 6]. Insulin/IGF-1 receptor mutations can also increase the lifespan of Drosophila [7]. In addition, mutations in chico, a downstream insulin receptor (IR) substrate-like signaling protein, increased the lifespan of the flies [8]. In mice, long-lived hereditary dwarf mice have been described [9]. Low levels of circulating growth hormone (GH) and IGF-1 in the Ames and Snell dwarf mice, which have pituitary defects, were associated with an extension of their lifespan [9]. Mutations in upstream genes that regulate insulin and IGF-1 also extended lifespan. For example, Little mice harbor a mutation in the GH-releasing hormone receptor and display reduced GH, as well as prolactin secretion [10]. Little mice also show reduced IGF-1 in blood, and have an increased mean and maximal lifespan [9]. Furthermore, GH receptor (GHR) mutant mice showed reduced circulating IGF-1 levels and an increased lifespan [11].

Although insulin/IGF-1 signaling controls the lifespan in mice, global deletion of insulin or IGF-1 causes early lethality associated with severe growth retardation. Mice lacking two nonallelic insulin genes, Ins1 and Ins2, died in the early postnatal stage [12], while more than 95% of IGF1-null mice died perinatally [13]. Unlike worms and flies, which have a single insulin/IGF-1-like receptor, mice have separate receptors for insulin and IGF-1. Mice with a global deletion of either the IR or the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) gene showed early postnatal lethality [14–16]. However, female mice with a heterozygous deletion of the IGF-1R displayed a 26% increase in mean lifespan [17]. IGF-1R heterozygous mice also showed mild growth retardation, but normal IGF-1 levels, as well as enhanced resistance to oxidative stress. In addition, mice that lack the IR gene in adipose tissue (FIRKO) live significantly longer than wild-type mice [18].

In a previous study, we generated a homologous murine model by replacing the Pro1195 of IR with Leu1195 using a targeted knock-in strategy to investigate the biological significance of longevity mutations found in the daf-2 mutant of C. elegans [19]. The homozygous mice died during the neonatal stage from diabetic ketoacidosis [19, 20], which was consistent with the phenotypes of IR-deficient mice [14, 16]. On the other hand, heterozygous mice showed suppressed kinase activity of the IR, but they grew normally without spontaneously developing hyperglycemia during adulthood. Furthermore, we demonstrated that IR mutant (Ir P1195L/wt) mice acquired an enhanced resistance to oxidative stress, such as exposure to 80% oxygen or paraquat. We also revealed that gender differences and dietary restriction are also associated with the defective insulin signaling [19].

In the present study, we investigated the lifespan of Ir P1195L/wt male and female mice under normoxia to clarify the insulin signaling resulting from a homologous mutation of daf-2 as a determinant of mammalian lifespan. Furthermore, we investigated the pathological consequences of the IR mutation related to systemic insulin resistance, because insulin signaling is generally regulated to the glucose metabolism in mammals. We herein reveal that the Ir P1195L/wt mice showed a normal lifespan and did not develop hyperglycemia, as is seen in diabetes mellitus (DM) patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Ir P1195L/wt mice [19] were backcrossed to C57BL6/NCrSlc mice (Japan SLC, Hamamatsu, Japan) for five or six generations. Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free facilities on a 12 h light/dark cycle (0800 on, 2000 off) and were fed an autoclaved standard chow (CRF-1; Oriental Yeast, Tokyo) and water ad libitum. The chow consisted of 54.5% (wt/wt) carbohydrate, 5.7% (wt/wt) fat, 22.4% (wt/wt) protein, and 3.1% (wt/wt) dietary fiber. Food intake was measured on a monthly basis until death. For measurement of the reproduction rate, we mated females with fertile males for four weeks at sexual maturity, and recorded the resulting pregnancies and offsprings. For measurement of rectal temperature, we used a digital thermometer with a rectal probe (BDT-100, Bio Research Center, Nagoya, Japan). All protocols for animal use and experiments were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology.

2.2. Lifespan Determination

By mating Ir P1195L/wt males or females with 8- to 20-week-old C57BL6/NCrSlc males or females, we generated two cohorts composed of 42 Ir P1195L/wt males and 64 Ir wt/wt males, and 50 Ir P1195L/wt females and 60 Ir wt/wt females. Male or female mice were randomly divided into four mice per a regular cage. We checked the mice daily and counted the number of dead mice. The body weights of mice were measured at 4-week intervals from 4-weeks after birth until death.

2.3. Histopathological Analysis

Mice were sacrificed via cervical dislocation. The pancreas was removed and fixed with mild formalin solution, and tissue samples were embedded in paraffin. Four-μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

2.4. Glucose Metabolism

The blood glucose concentrations were determined in fasting mice (3-, 12-, 18-, and 25-months old) using an automatic monitor, the Glucocard (Arkray, Kyoto, Japan). The serum insulin levels were measured in 4-, 9-, and 25-month-old mice. Serum obtained from nonfasting or fasting mice was analyzed for insulin using a Mouse Insulin ELISA kit (Shibayagi, Shibukawa, Japan). During glucose tolerance tests, mice fasted overnight and then received intraperitoneally injections of 2 g/kg body weight of 20% D-glucose. The blood glucose concentrations were determined in whole blood obtained from the tail at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes after the glucose injection. For the insulin tolerance tests, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 U/kg body weight of insulin (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis), then the blood glucose concentrations were measured at 0, 15, 30, and 60 minutes after the injection. The serum adiponectin concentrations were measured in nonfasting mice (4-month-old) using a Mouse/Rat Adiponectin ELISA kit (Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan).

2.5. Adipose Tissues and Bone Examination

Mice were sacrificed at 20 months of age and scanned three times using a Lunar PIXImus2 densitometer (GE Healthcare Lunar, Madison, Wis, USA). All mice were fasted for 3 hours before the DEXA.

2.6. Respirometry Monitoring Using Metabolic Cages

Oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide excretion (VCO2) values were measured in 5-month-old male mice (n = 3) using an O2/CO2 metabolism measuring system for small animals (MK-5000RQ, Muromachi Kikai). The mice were isolated in a semisealed cage, and the inner air was aspirated at a constant volume/min (approx., 0.65–0.70 l/min). The concentrations of O2 and CO2 in the aspirated air were measured per minute at intervals of 3 minutes, and automatically corrected using standard O2 and CO2 values. The respiratory quotient (RQ) values were calculated by the VCO2/VO2.

3. Results

3.1. Ir P1195L/wt Mice Have a Normal Lifespan

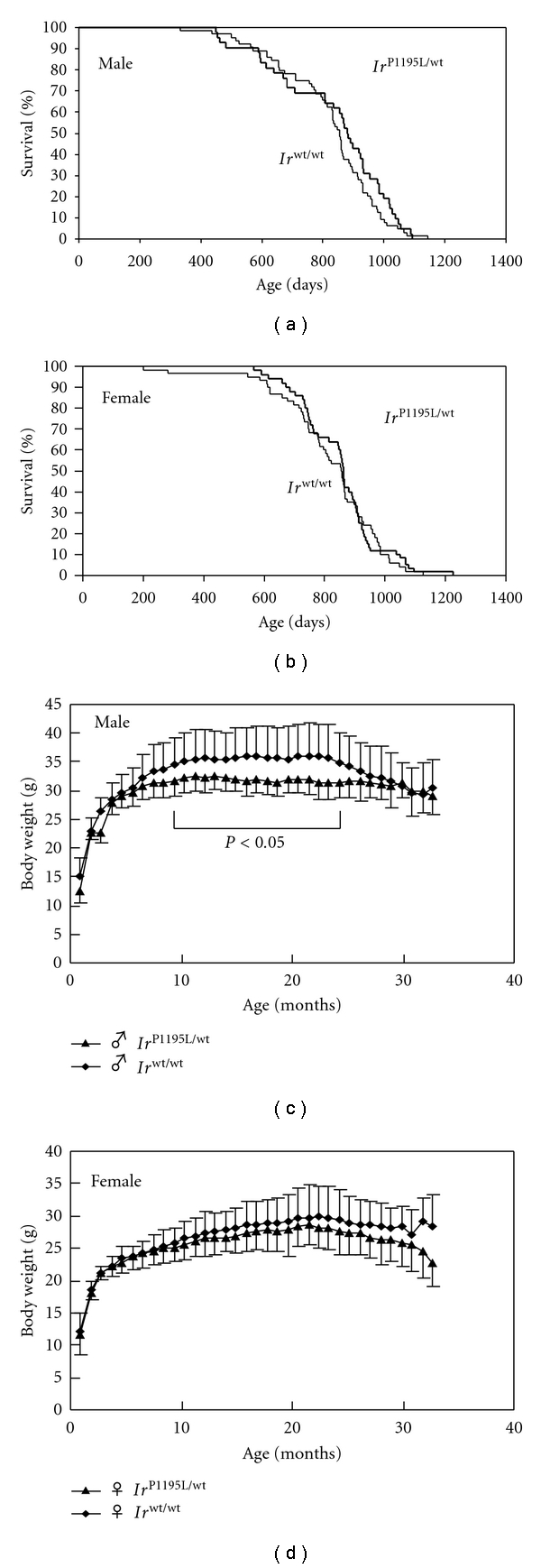

In order to evaluate the lifespan of Ir P1195L/wt mice, we compared the 50% survival and maximum lifespan of Ir P1195L/wt mice with those of wild-type (Ir wt/wt) mice. As shown in Figure 1(a), the Ir P1195L/wt male mice failed to show an extended lifespan compared to the Ir wt/wt male mice. Likewise, the Ir P1195L/wt female mice also failed to show any increase in survival compared to the Ir wt/wt female mice (Figure 1(b)). A Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the 50% survival of Ir P1195L/wt male and Ir wt/wt male mice was 883 days (29.0 months) and 855 days (28.1 months), respectively (Figure 1(a)). In females, the 50% survival of Ir P1195L/wt and Ir wt/wt mice was 863 days (28.4 months) and 856 days (28.1 months), respectively (Figure 1(b)). The maximum lifespans of the Ir wt/wt male and female mice were 1,144 days (37.6 months) and 1,226 days (40.3 months), respectively. Those of the Ir P1195L/wt male and female mice were 1,092 days (35.9 months) and 1,126 days (37.0 months), respectively (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). The results demonstrated that the introduction of an IR mutation does not extend the lifespan of male and female mice (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)).

Figure 1.

The survival curves and body weights of Ir P1195L/wt mice. (a) The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Ir P1195L/wt male (n = 42) and Ir wt/wt male (n = 64) mice (generalized Wilcoxon test, P = 0.33). Bold and thin lines indicate Ir P1195L/wt and Ir wt/wt mice, respectively. (b) The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Ir P1195L/wt female (n = 50) and Ir wt/wt female (n = 60) mice (generalized Wilcoxon test, P = 0.42). (c, d) The body weights of male (c) and female (d) mice. The Ir P1195L/wt male mice (n = 28) showed significantly decreased body weight compared to that of Ir wt/wt male mice (n = 36) from 9 to 25 months of age, while the Ir P1195L/wt female mice (n = 39) failed to show any significant difference compared to the Ir wt/wt female mice (n = 47). Closed triangles and closed diamonds indicate Ir P1195L/wt and Ir wt/wt mice, respectively.

Since the Ir P1195L/wt male and female mice exhibited a reduction in body weight at 4 months of age compared to the wild type mice [19], we measured the body weight from 1 to 32 months. The body weight of Ir P1195L/wt male mice was lower than that of the Ir wt/wt mice from 9 months to 25 months, while the Ir P1195L/wt female mice failed to exhibit any difference in body weight compared to the wild-type mice throughout their entire lifespan (Figures 1(c) and 1(d)).

3.2. Ir P1195L/wt Mice Exhibit Hyperinsulinemia but Do Not Develop Hyperglycemia

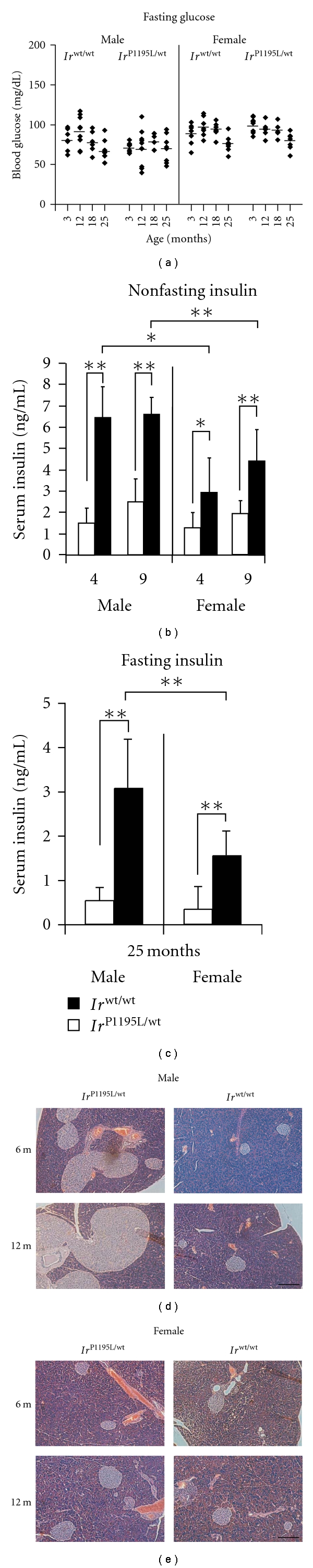

In order to determine whether the suppression of IR signaling impairs glucose metabolism in aged male and female mice, we measured the blood glucose (Figure 2(a)) and serum insulin (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)) levels in the Ir P1195L/wt male and female mice. In a fasting condition, the Ir P1195L/wt male and female mice did not develop hyperglycemia at any point throughout their entire lifespan (3 to 25 months of age, Figure 2(a)). However, the serum insulin concentrations in the non-fasting state were significantly increased in 4- and 9-month-old male and female mutant mice compared to Ir wt/wt mice (Figure 2(b)). Furthermore, we also found increased insulin concentrations in aged Ir P1195L/wt males and females compared to the Ir wt/wt male and female mice under a fasting condition (Figure 2(c)). Although we failed to detect any gender differences in the insulin concentrations of Ir wt/wt mice, the insulin concentrations of aged Ir P1195L/wt males were significantly increased compared to aged Ir P1195L/wt females (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)). The histological analysis showed the enlargement of Langerhans islets in the pancreas of Ir P1195L/wt mice at 6 and 12 months of age (Figures 2(d) and 2(e)). In particular, Ir P1195L/wt male mice exhibited an extensive hyperplasia of the islets. These results suggest that aged Ir P1195L/wt mice maintained hyperinsulinemia, due to the proliferation of β-cells in islets, and did not develop hyperglycemia during aging.

Figure 2.

The blood glucose and serum insulin concentrations in Ir P1195L/wt mice. (a) The blood glucose concentrations of fasting mutant male and female mice were assessed. All Ir P1195L/wt mice exhibited blood glucose concentrations within the same range as the Ir wt/wt mice (n = 6–10 for each genotype). (b) The serum insulin concentrations were determined in the nonfasting state of 4- and 9-month-old Ir wt/wt and Ir P1195L/wt mice (n = 7 for each genotype). (c) The serum insulin concentrations were determined in the fasting state of 25-month-old Ir wt/wt and Ir P1195L/wt mice (n = 5 for each genotype). The insulin concentrations were significantly increased in both female and male Ir P1195L/wt mice compared with the Ir wt/wt mice. (d, e) The histochemical analyses of the pancreas of Ir P1195L/wt mice. (d) The Ir P1195L/wt male mice exhibited extensive enlargement of the Langerhans islets compared to Ir wt/wt mice. (e) In addition, the size of islets in Ir P1195L/wt female mice was larger than in Ir wt/wt female mice. The scale bars indicate 200 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 by Student's t-test.

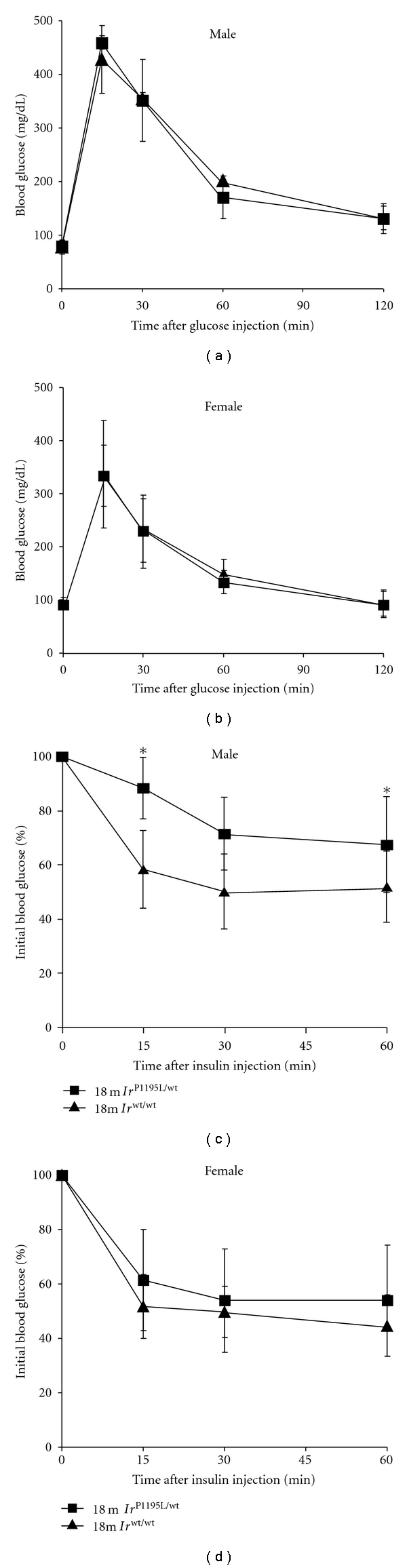

In order to determine the physiological compensation for the mutation of the IR gene, we assessed the glucose and insulin tolerances of Ir P1195L/wt mice at 18 months of age. We previously reported that young Ir P1195L/wt male mice showed glucose intolerance and reduced insulin sensitivity, while Ir P1195L/wt females did not show these tolerances, in spite of hyperinsulinemia [19]. In the glucose tolerance test, the 18-month-old Ir P1195L/wt male and female mice both showed a normal glucose tolerance (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). On the other hand, aged Ir P1195L/wt male mice had impaired insulin sensitivity (Figure 3(c)), while aged Ir P1195L/wt females and Ir wt/wt females reacted similarly to insulin administration (Figure 3(d)). Based on the data about glucose metabolism in young and aged mice, we suggested that Ir P1195L/wt male mice maintained reduced insulin sensitivity during aging, but that the Ir P1195L/wt female mice did not.

Figure 3.

The results of the glucose and insulin tolerance tests in aged Ir P1195L/wt mice. (a, b) Glucose tolerance tests were performed on 18-month-old Ir wt/wt and Ir P1195L/wt mice (n = 5 for each genotype). (c, d) Insulin tolerance tests were performed on 18-month-old Ir wt/wt and Ir P1195L/wt mice (n = 5 in each genotype). *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test.

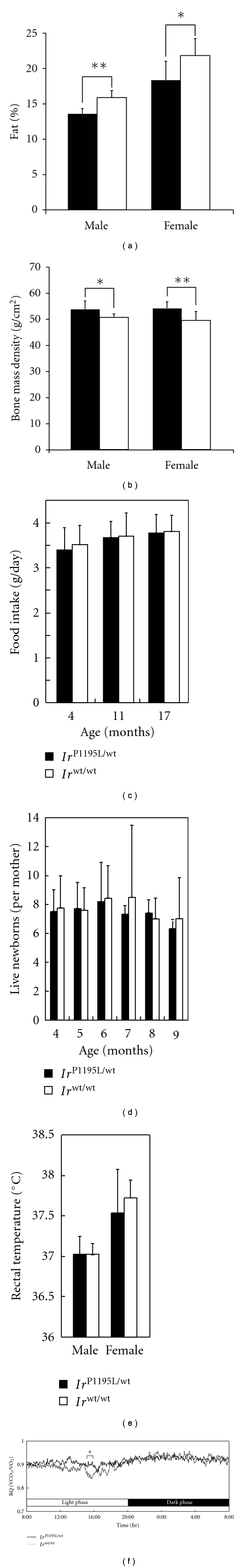

3.3. Ir P1195L/wt Mice Show a Reduction of Adipose Tissue and Enhancement of Bone Density

In the previous study, we showed a reduction of perigonadal adipose tissues in Ir P1195L/wt male and female mice [19]. To assess the overall distribution of adipose tissues in mutant mice at 20 months of age, we measured the adipose mass by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). The Ir P1195L/wt male and female mice showed a significantly reduced adipose mass (Figure 4(a)). Since the circulating adiponectin levels negatively correlate with visceral adiposity in humans [21], we measured the serum adiponectin concentrations in non-fasting Ir P1195L/wt mice. The adiponectin concentrations in the Ir P1195L/wt mice were not increased compared to Ir wt/wt mice (male; 23.7 ± 2.8 versus 27.0 ± 7.6 μg/mL, female; 44.8 ± 5.0 versus 42.3 ± 3.3 μg/ml, resp.,) at 4 months of age, suggesting that the reduced adiposity induced by altered IR signaling might be insufficient to enhance the secretion of adiponectin from adipose tissues in Ir P1195L/wt mice.

Figure 4.

Adiposity, bone density, food intake, reproduction, rectal temperature, and respiratory quotients of the Ir P1195L/wt mice. (a) Both male and female Ir P1195L/wt mice showed a significantly decreased fat ratio compared to Ir wt/wt mice at 20 months of age. (b) Both male and female Ir P1195L/wt mice showed significantly increased bone density compared to the Ir wt/wt mice at 20 months of age. Aged Ir P1195L/wt male (n = 6), Ir P1195L/wt female (n = 6), Ir wt/wt male (n = 6), and Ir wt/wt female (n = 5) mice were evaluated by DEXA. (c) The food intake of Ir P1195L/wt male and Ir wt/wt male mice at 4, 11, and 17 months of age. No significant difference was observed between the food consumption by Ir P1195L/wt (n = 10) and Ir wt/wt (n = 12) mice. (d) The reproduction rate of Ir P1195L/wt female mice. No significant difference was observed between Ir P1195L/wt and Ir wt/wt mice (at least 3 mice per genotype). (e) The rectal temperatures of Ir P1195L/wt and Ir wt/wt mice at 4 months of age. No significant differences were observed in the temperatures between the Ir P1195L/wt and Ir wt/wt mice (n = 4 for each genotype). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 by Student's t-test. (f) The mean time course of respiratory quotients (RQ = VCO2/VO2) of male mice at 5 months of age. The values represent the mean of 24 hours of measurements from each animal (n = 3, male). *P < 0.05 by Student's t-test.

Since osteoblasts and adipocytes are differentiated from common progenitor cells in the bone marrow [22–24], we assumed that the common progenitor cells of Ir P1195L/wt mice had differentiated into osteoblasts, which would lead to enhanced bone formation instead of generating adipose tissue in these mice. The DEXA analysis demonstrated that there was a significant increase in the bone density in aged Ir P1195L/wt mice (Figure 4(b)). Interestingly, 4-month-old Ir P1195L/wt mice failed to exhibit any significant difference in bone density compared to 4-month-old Ir wt/wt mice (data not shown). These results suggested that one of the beneficial effects of the Ir P1195L/wt genotype in the later stage of life is due to the reduction of adipose mass associated with the enhancement of bone density.

3.4. Ir P1195L/wt Mice Show Normal Food Intake, Reproduction Rates, Rectal Temperatures, and Metabolism

Since dietary restriction can prolong the lifespan of animals [25], we compared the food intake of Ir P1195L/wt mice with that of Ir wt/wt mice. We failed to detect any significant difference in food intake between the Ir P1195L/wt and Ir wt/wt mice (Figure 4(c)), suggesting that dietary restriction did not affect the lifespan of the Ir P1195L/wt mice. Since long-lived dwarf mice display reduced fecundity [9], we measured the reproduction rate in Ir P1195L/wt female mice. As shown in Figure 4(d), the results indicated that the Ir P1195L/wt mice reproduced to generate a number of pups comparable to the number produced by Ir wt/wt female mice.

A relationship between low body temperature and lifespan has been reported in long-lived Ames dwarf mice and rhesus monkeys on dietary restriction [26–28]. Therefore, we measured the rectal temperature of Ir P1195L/wt mice. We failed to detect any significant differences in the rectal temperatures between Ir P1195L/wt and Ir wt/wt mice (Figure 4(e)). Since metabolism may have an important role in aging, we also analyzed voluntarily running distance to evaluate the physical activity in Ir P1195L/wt mice. However, we did not observe any substantial differences in running distance for 14 days between Ir P1195L/wt male and Ir wt/wt male mice (data not shown). We also measured the VO2 and VCO2 of the mice in metabolic cages. Although the respiratory quotient value of the Ir P1195L/wt males was slightly increased in the light phase, the Ir P1195L/wt mice showed comparable metabolism to Ir wt/wt male mice (Figure 4(f)). These results suggested that the Ir P1195L/wt mice did not have modulation in their metabolism, such as reduced food intake, lower body temperature, or any differences in their physical activity, respiratory quotient, or reproductive activities.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Biological Roles of Insulin Signaling in Adipose Tissue for Lifespan Extension

Bluher et al. reported that specific deletion of the IR gene in adipose tissues extended the lifespan of FIRKO mice [18]. FIRKO mice also showed reduced adiposity, as well as normal food intake. The authors suggested in that paper that leanness, not dietary restriction, is a key contributor to an extended lifespan [18]. Since IR signaling was completely downregulated in the adipose tissues of FIRKO mice, but was normal in other tissues, the loss of insulin signaling might confer a reduction of fat mass in adipose tissues. In the present study, we observed that the Ir P1195L/wt mice displayed a reduction in fat mass with normal food intake (Figures 4(a) and 4(d)), indicating that the Ir P1195L/wt mice showed similar phenotypes to the FIRKO mice with respect to their adiposity. However, the Ir P1195L/wt mice failed to show an extended lifespan, in contrast to the FIRKO mice (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). Although the differences in the beneficial effects on lifespan in these mutant mice is still unclear, we believe that there are three possible reasons for these differences, as described below.

First, the reduced fat mass in Ir P1195L/wt mice was not sufficient to extend the lifespan of these mice, while the reduced level in the FIRKO mice was sufficient to produce a lifespan change. In fact, we failed to observe any difference in the serum adiponectin concentration between the Ir P1195L/wt and wild-type mice. Second, in contrast to the IR mutation of Ir P1195L/wt mice, the IR insufficiency, specifically in the adipose tissues of the FIRKO mice, might modulate their lifespan by an independent mechanism. The insulin signaling in adipose tissues of FIRKO mice might promote the differential regulation of the biosynthesis of adipokines such as adiponectin, leptin, tumor-necrosis factor-α, resistin, and retinol binding protein-4. Third, FIRKO mice exhibited tissue-specific reduced insulin signaling in adipose tissues. In contrast, global insulin resistance due to a systemic IR mutation might inhibit the beneficial effects of a reduced fat mass on lifespan extension in mice.

4.2. IGF-1 Receptor Signaling May Dominantly Regulate the Lifespan in Mice

It is unclear whether the IR or IGF-1R corresponds to the function of daf-2 in C. elegans with regard to the lifespan regulation in vertebrates. Holzenberger et al. reported that both male and female IGF-1R gene heterozygous mice showed an extended lifespan, with normal fertility, and that they also showed an increased resistance to oxidative stress [17]. Since the mutation introduced in the IR gene presented in this paper showed a dominant negative effect, and the tyrosine kinase activities were severely down-regulated, it is difficult to directly compare its phenotype with IGF-1R-deficient mice that show haploinsufficiency in IGF-1R signaling. Although decreased IGF-1R signaling prolonged the lifespan in IGF-1R mutant mice, altered IR signaling failed to extend the lifespan in Ir P1195L/wt mice. Another line of evidence for the importance of IGF-1R signaling in lifespan regulation is that long-lived dwarf mice display low levels of GH and circulating IGF-1 [29, 30]. Furthermore, targeted inactivation of the GH receptor also showed a decrease in the circulating IGF-1 level, and increased lifespan [11]. These results revealed that IGF-1 signaling might dominantly regulate the lifespan in mice, while insulin signaling might mainly regulate glucose and energy metabolism, rather than lifespan.

4.3. Comparison of Ir Mutant Mice with Other Long-Lived Mutant Mice, Including Klotho Tg, Irs1, Irs2, and S6K Mutant Mice, on Lifespan Extension

Kurosu et al. reported that overexpression of the Klotho gene extends the lifespan in male and female mice [31]. Two lines of Klotho Tg mice also showed reduced fecundity in females and insulin resistance in both genders. When the soluble Klotho protein was intraperitoneally administered to wild-type mice, the insulin and IGF-1 sensitivity of the mice was impaired, indicating that increased Klotho protein in the blood induced insulin resistance, as well as IGF-1 resistance. Since the Ir P1195L/wt mice also showed insulin resistance, but not IGF-1 resistance, IGF-1 resistance might be necessary for the lifespan extension in mice. This result is consistent with the reduced IGF-1 signaling observed in Igf1r +/− and long-lived dwarf mice.

Recently, Taguchi et al. and Selman et al. reported that mice with mutations in Irs1 and Irs2, components of the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway, showed an extended lifespan and reduced insulin sensitivity [32, 33]. Selman et al. also reported that deletion of ribosomal S6 protein kinase (S6K), a component of the nutrient-responsive mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway, led to an increased lifespan and loss of insulin sensitivity [34]. Taken together with these reports, our results suggest that reduced insulin sensitivity has a limited effect on the lifespan in mice.

4.4. Oxidative Stress and Lifespan in Ir P1195L/wt Mice

Long-lived nematode and fly mutants with altered insulin signaling generally acquire enhanced resistance to oxidative stress [3, 7, 8, 35]. Furthermore, long-lived dwarf, Igf1r +/−, and p66shc-/− mice also showed enhanced resistance to paraquat [9, 17, 36]. In our previous study, we reported that Ir P1195L/wt male and female mice also showed significantly enhanced resistance to oxidative stress, such as hyperoxia and paraquat [19]. Furthermore, Ir P1195L/wt female mice survived longer than Ir P1195L/wt male mice in an 80% oxygen chamber, suggesting that sex hormones modulate the resistance to oxidative stress in mice. We also demonstrated that estrogen modulated the resistance to oxidative stress by estrogen administration in male and ovariectomy in female mice. In the present study, however, the Ir P1195L/wt female mice failed to show any increase in survival under normoxia (Figure 1(c)). Likewise, the Ir P1195L/wt male mice showed a normal lifespan (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). These results indicate that the resistance to oxidative stress is not correlated with the lifespan in mice. Although we are unable to exclude the possibility that other limiting factors modulated the lifespan in Ir P1195L/wt mice, we suggest that the enhanced resistance to oxidative stress is not a major determinant for lifespan extension in mice.

4.5. Ir P1195L/wtMice Show a Normal Lifespan, without Developing Hyperglycemia

Mutations in the IR gene cause insulin resistance syndromes, such as leprehaunism, Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome, and type A insulin resistance [37, 38]. We introduced a mutation substituting a Leu1195 for the Pro1195 residue in the β chain of Ir P1195L/wt mice. This mutation corresponds to a homologous mutation substituting a Leu1178 for the Pro1178 residue of the human IR in patients with type A insulin resistance found in Japanese and British patients [39, 40]. A Japanese patient with the orthologous mutation showed obesity, moderate insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans, and hyperandrogenism with normal glucose tolerance [39]. The authors of that paper suggested that insulin resistance and the other clinical features observed in the patient were due to obesity rather than the mutation in the IR gene [39]. Interestingly, Krook et al. reported that a type A Cam-3 patient with an orthologous mutation presented with oligomenorrhea, hirsutism, and acanthosis nigricans at 13 years of age [40]. She subsequently developed hyperglycemia. Moreover, the authors described in this paper that the patient had inherited the IR mutation from her father, who was clinically normal but had a moderate elevation of his fasting insulin. The patient's mother and sister also had moderate hyperinsulinemia, which suggests that there was a second defect in this patient [40]. In this context, we speculated that there was a heterozygous mutation in the father or mother of the British patient who had hyperinsulinemia without developing hyperglycemia, while the second defect in the patient led to severe insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. Based on these reports and our present data, we suggested that the heterozygosity of the orthologous mutation with the kinase domain of the IR gene leads to moderate insulin resistance with hyperinsulinemia, but does not lead to the development of hyperglycaemia in mice or humans.

Kido et al. reported that genetic modifiers of insulin resistance influence the phenotype in IR-deficient mice [41]. On the genetic background of B6 mice, the haploinsufficiency of the IR gene caused mild hyperinsulinemia. In contrast, on the genetic background of 129/Sv mice, the same mutation caused severe hyperinsulinemia, suggesting that the 129/Sv strain harbors alleles that interact with the IR mutation and predispose these mice to insulin resistance [41]. Interestingly, these data were obtained for males, while females did not develop hyperinsulinemia on either background. These studies also indicated that 5-10% of IR+/− mice on the B6 background developed hyperglycemia, while 25% of IR+/− mice on the 129/Sv background developed hyperglycemia [41, 42]. Thus, the B6 strain is relatively resistant to the deleterious effects of the haploinsufficiency of the IR gene. Since we developed our Ir P1195L/wt mice on a B6 genetic background, further analyses in mice of a different background may provide us with information about the genetic modifier(s) and help evaluate the pathological effects of the IR mutation on the development of hyperglycemia.

5. Conclusion

In the present study, we showed that Ir P1195L/wt mice showed a normal lifespan, as well as hyperinsulinemia, and they did not develop hyperglycemia throughout their lifespan. This study provides evidence that insulin signaling does not make a major contribution to regulating the lifespan in mammals. A further analysis of altered insulin signaling using Ir P1195L/wt mice, especially those developed on another background, should provide us with a useful strategy for the prevention of age-associated diseases, such as type 2 DM in humans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Eiko Moriizumi for the histological analysis and measurement of body weight. They also thank Doctors Satoshi Uchiyama, Hirotomo Kuwahara, Hiroshi Sakuramoto, and Satoru Kawakami of the TMIG for their technical assistance. This work was supported by grants for Comprehensive Research on Aging and Health from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (T. Shir).

References

- 1.Kenyon C. The plasticity of aging: insights from long-lived mutants. Cell. 2005;120(4):449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partridge L, Gems D, Withers DJ. Sex and death: what is the connection? Cell. 2005;120(4):461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366(6454):461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimura KD, Tissenbaum HA, Liu Y, Ruvkun G. Daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;277(5328):942–946. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin K, Dorman JB, Rodan A, Kenyon C. daf-16: an HNF-3/forkhead family member that can function to double the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;278(5341):1319–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogg S, Paradis S, Gottlieb S, et al. The Fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature. 1997;389(6654):994–999. doi: 10.1038/40194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatar M, Kopelman A, Epstein D, Tu MP, Yin CM, Garofalo RS. A mutant Drosophila insulin receptor homolog that extends life-span and impairs neuroendocrine function. Science. 2001;292(5514):107–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1057987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clancy DJ, Gems D, Harshman LG, et al. Extension of life-span by loss of CHICO, a Drosophila insulin receptor substrate protein. Science. 2001;292(5514):104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1057991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartke A, Brown-Borg H. Life extension in the dwarf mouse. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2004;63:189–225. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)63006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eicher EM, Beamer WG. New mouse dw allele: genetic location and effects on lifespan and growth hormone levels. Journal of Heredity. 1980;71(3):187–190. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coschigano KT, Clemmons D, Bellush LL, Kopchick JJ. Assessment of growth parameters and life span of GHR/BP gene-disrupted mice. Endocrinology. 2000;141(7):2608–2613. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.7.7586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duvillié B, Cordonnier N, Deltour L, et al. Phenotypic alterations in insulin-deficient mutant mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(10):5137–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker J, Liu JP, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Role of insulin-like growth factors in embryonic and postnatal growth. Cell. 1993;75(1):73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Accili D, Drago J, Lee EJ, et al. Early neonatal death in mice homozygous for a null allele of the insulin receptor gene. Nature Genetics. 1996;12(1):106–109. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu JP, Baker J, Perkins AS, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Mice carrying null mutations of the genes encoding insulin-like growth factor I (Igf-1) and type 1 IGF receptor (Igf1r) Cell. 1993;75(1):59–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi RL, Lamothe B, Cordonnier N, et al. Targeted disruption of the insulin receptor gene in the mouse results in neonatal lethality. The EMBO Journal. 1996;15(7):1542–1547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzenberger M, Dupont J, Ducos B, et al. IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature. 2003;421(6919):182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature01298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blüher M, Kahn BB, Kahn CR. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science. 2003;299(5606):572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1078223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baba T, Shimizu T, Suzuki YI, et al. Estrogen, insulin, and dietary signals cooperatively regulate longevity signals to enhance resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(16):16417–16426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogino J, Sakurai K, Yoshiwara K, et al. Insulin resistance and increased pancreatic β-cell proliferation in mice expressing a mutant insulin receptor (P1195L) Journal of Endocrinology. 2006;190(3):739–747. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Shimomura I. Adiponectin and metabolic syndrome. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2004;24(1):29–33. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099786.99623.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akune T, Ohba S, Kamekura S, et al. PPARγ insufficiency enhances osteogenesis through osteoblast formation from bone marrow progenitors. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113(6):846–855. doi: 10.1172/JCI19900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beresford JN, Bennett JH, Devlin C, Leboy PS, Owen ME. Evidence for an inverse relationship between the differentiation of adipocytic and osteogenic cells in rat marrow stromal cell cultures. Journal of Cell Science. 1992;102(2):341–351. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weindruch R, Walford RL, Fligiel S, Guthrie D. The retardation of aging in mice by dietary restriction: longevity, cancer, immunity and lifetime energy intake. Journal of Nutrition. 1986;116(4):641–654. doi: 10.1093/jn/116.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter WS, Croson WB, Bartke A, Gentry MV, Meliska CJ. Low body temperature in long-lived Ames dwarf mice at rest and during stress. Physiology and Behavior. 1999;67(3):433–437. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth GS, Lane MA, Ingram DK, et al. Biomarkers of caloric restriction may predict longevity in humans. Science. 2002;297(5582):p. 811. doi: 10.1126/science.1071851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane MA, Baer DJ, Rumpler WV, et al. Calorie restriction lowers body temperature in rhesus monkeys, consistent with a postulated anti-aging mechanism in rodents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(9):4159–4164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown-Borg HM, Borg KE, Meliska CJ, Bartke A. Dwarf mice and the ageing process. Nature. 1996;384(6604):p. 33. doi: 10.1038/384033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flurkey K, Papaconstantinou J, Miller RA, Harrison DE. Lifespan extension and delayed immune and collagen aging in mutant mice with defects in growth hormone production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(12):6736–6741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111158898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, et al. Physiology: suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science. 2005;309(5742):1829–1833. doi: 10.1126/science.1112766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taguchi A, Wartschow LM, White MF. Brain IRS2 signaling coordinates life span and nutrient homeostasis. Science. 2007;317(5836):369–372. doi: 10.1126/science.1142179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selman C, Lingard S, Choudhury AI, et al. Evidence for lifespan extension and delayed age-related biomarkers in insulin receptor substrate 1 null mice. FASEB Journal. 2008;22(3):807–818. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9261com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selman C, Tullet JMA, Wieser D, et al. Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 signaling regulates mammalian life span. Science. 2009;326(5949):140–144. doi: 10.1126/science.1177221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408(6809):239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Migliaccio E, Giogio M, Mele S, et al. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature. 1999;402(6759):309–313. doi: 10.1038/46311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor SI. Lilly lecture: molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance: lessons from patients with mutations in the insulin-receptor gene. Diabetes. 1992;41(11):1473–1490. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.11.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor SI, Cama A, Accili D, et al. Mutations in the insulin receptor gene. Endocrine Reviews. 1992;13(3):566–595. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-3-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim H, Kadowaki H, Sakura H, et al. Detection of mutations in the insulin receptor gene in patients with insulin resistance by analysis of single-stranded conformational polymorphisms. Diabetologia. 1992;35(3):261–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00400927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krook A, Kumar S, Laing I, Boulton AJM, Wass JAH, O’Rahilly S. Molecular scanning of the insulin receptor gene in syndromes of insulin resistance. Diabetes. 1994;43(3):357–368. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kido Y, Philippe N, Schäffer AA, Accili D. Genetic modifiers of the insulin resistance phenotype in mice. Diabetes. 2000;49(4):589–596. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kido Y, Burks DJ, Withers D, et al. Tissue-specific insulin resistance in mice with mutations in the insulin receptor, IRS-1, and IRS-2. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;105(2):199–205. doi: 10.1172/JCI7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]