Abstract

The NudC family consists of four conserved proteins with representatives in all eukaryotes. The archetypal nudC gene from Aspergillus nidulans is a member the nud gene family, involved in maintenance of nuclear migration. This family also includes nudF whose human orthologue, Lis1, codes for a protein essential for brain cortex development. Three paralogues of NudC are known in vertebrates, NudC, NudC-like (NudCL) and NudC-like 2 (NudCL2). The fourth distantly related member of the family, CML66, contains a NudC-like domain. The three principal NudC proteins have no catalytic activity, but appear to play as yet poorly defined roles in proliferating and dividing cells. We present crystallographic and NMR studies of the human NudC protein, and discuss the results in the context of structures recently deposited by Structural Genomics centers, i.e. NudCL and mouse NudCL2. All proteins share the same core CS-domain characteristic for proteins acting either as co-chaperones of Hsp90, or as independent small heat shock proteins. However, while NudC and NudCL dimerize via an N-terminally located coiled-coil, the smaller NudCL2 lacks this motif and instead dimerizes as a result of unique domain swapping. We show that NudC and NudCL, but not NudCL2, inhibit aggregation of several target proteins, consistent with an Hsp90-independent heat shock protein function. Importantly, and in contrast to several previous reports, none of the three proteins are able to form binary complexes with Lis1. The availability of structural information will be of help in further studies of cellular functions of the NudC family.

Keywords: Protein structure, crystallography, nuclear migration, chaperones, protein-protein interactions

Introduction

The nuclear distribution (nud) gene family was originally identified in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans (or Emericella nidulans in its sexual form), as a set of genes associated with dynein-dependent, nuclear migration 1–6. In a healthy organism during the vegetative growth the nuclei migrate towards the growing tip of the hyphae5, whereas in mutants with impaired nud genes the nuclei are clustered together following karyokinesis and unable to undergo translocation2. The nud family became a focus of intense interest when it was discovered that one of its members, nudF, encoded a close homologue (42% amino acid sequence identity) of the mammalian Lis1 protein, which is mutated in a debilitating developmental genetic syndrome known as the Miller-Dieker lissencephaly 3,7–9. In afflicted individuals the brain cortex is smooth, without typical groves, or sulci, because the layer structure is partly or wholly disrupted due to the inability of young neurons to migrate from the ventricular zone to their target destinations. Thus, there has been considerable speculation that the nuclear migration pathway observed in Aspergillus has been evolutionarily conserved and acquired a new function in fetal brain development.

As expected, some of the nud genes code for components of cytoplasmic motor dynein and dynactin, directly responsible for translocation of the nucleus along microtubules10. Three nud genes that do not belong to this group are: nudF, nudE and nudC. As already stated, the 45 kDa NudF is a homologue of the mammalian Lis1 protein, which is now known to be a dynein regulator, and also a component of the brain isoform of the platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH II)11,12. The NudE protein is represented in mammalian genomes by two paralogues, NudE and NudEL, currently renamed Nde1 and Ndel113–15. Each protein, just over 300 residues in length, contains a conserved 160-residue long parallel coiled-coil domain at the N-terminus, which binds the homodimeric Lis1 16. The details of how this complex interacts with and regulates dynein are still debated, but recent data suggest that LIS1 alone, or with Nde1/Ndel1, induces a persistent-force state in dynein17.

Of all the nud gene products, NudC has been the most elusive with respect to its function. The deletion of the nudC gene in Aspergillus produces a severe phenotype with a much thicker cell wall compared to wild type 18. Recently published data suggest that NudC and NudF form a complex in the fungus essential for the proper function of the spindle pole bodies (SPB)19. Orthologues of NudC have been identified in higher eukaryotes, including C. elegans20, D. melanogaster21, amphibians (newt) 22 and mammals. In most, if not all, Metazoa, three paralogues are found: hNudC23,24, hNudC-like (NudCL, also annotated as NudC domain containing protein 3)25, and hNudC-like 2 (NudCL2, or NudC domain containing protein 2) 26. The length of polypeptide chains differs among the three, but they all contain a single globular domain with significant amino acid sequence conservation 27. A similar domain is also found in the fourth member of this family, the NudC-domain containing protein 1 28,29. This enigmatic protein, also known as CML66 is a tumor antigen implicated in stimulating tumor cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis, but its function is unknown28

The physiological functions of the mammalian NudC paralogues are far from understood. The vast majority of the reported research focused on NudC. It is expressed in all tissues, both in the fetus and in the adult organism 24, but at a particularly high level in cell lines and proliferating cells of normal tissues30, indicating a possible role in cell division. Indeed, down regulation of human NudC mRNA results in impairment of both cell proliferation and mitotic spindle formation 31. There is also evidence that NudC is involved in cytokinesis in a phosphorylation-dependent fashion32–34. As might be expected, a protein involved in mitotic cell division is also found to play a role in cancer. For example, there is an inverse correlation between NudC expression and nodal metastasis in esophageal cancer35, and an adenovirus expressing NudC was able to inhibit the growth of prostate tumors by blocking cell division36. In apparent contrast, NudC was identified as one of the over-expressed genes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma 37, and was found expressed in neuroectodermal tumors, but not in non-neoplastic brain tissue 38. Moreover, high expression levels were associated with cells infiltrating white matter or undergoing division38.

Unfortunately, the details of the specific molecular mechanisms in which NudC is involved are very elusive. Several reports implicate NudC in direct interactions with Lis1 39–42; others suggest interactions with kinesin-143, and polo-like kinase32,44. A recent study lists 131 (sic) proteins identified by mass spectrometry as potential binding partners of NudC 40. Further, there is evidence that NudC may function as a chaperone, effectively stabilizing its target proteins or enhancing folding. This potentially includes both Hsp90-dependent pathway40 and direct chaperone activity40,44. Finally, there is a set of papers exploring the hypothesis that NudC is a secreted protein which functions by binding to the extracellular domain of the thrombopoietin receptor 45–50.

The remaining two paralogues, NudCL and NudCL2 were only recently discovered and are just beginning to attract attention. So far, NudCL has been implicated in enhancing the stability of the dynein intermediate chain25, while NudCL2 in stabilizing Lis1 through the Hsp90 pathway26. An exhaustive review of the nudC-like genes has appeared recently51.

To better understand structure-function relationships in the NudC family, we undertook a systematic structural characterization of hNudC using heteronuclear NMR and X-ray crystallography. While this work was in progress, several structures of NudC homologues, or their fragments, were deposited in the Protein Data Bank by Structural Genomics Centers. In this paper, we take advantage of this novel information, and present an overview of structural features of the NudC family. Further, we re-visit the question of the interactions of NudC proteins with Lis1 and their intrinsic chaperone activities.

Results and Discussion

The amino acid sequence features of the NudC-family proteins: an overview

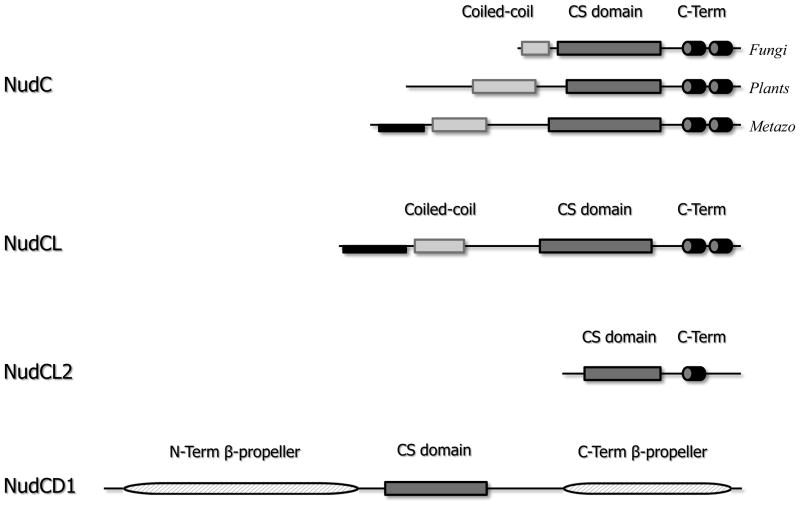

A number of important features relevant to the molecular architecture of the NudC protein family can be inferred from the amino acid sequence comparisons (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

The molecular architecture of the proteins in the NudC family. The CS-domain is shown in dark grey. The C-terminal black α-helices and black intrinsically disordered fragment at the N-terminus are the regions of highest amino acid conservation within the NudC and NudCL subfamilies. The two putative β-propeller sections (hashed) shown for NudCD1, are likely to constitute two halves of a split domain.

The prototypical member of the NudC family, the Aspergillus nidulans protein, contains 198 amino acids. The first thirty amino acids show propensity to form coiled-coil, as inferred from sequence-based prediction52. It has been predicted that a single globular domain, with apparent similarity to p23 and other small heat shock proteins 27, spans residues 36–116. Downstream of this domain, secondary structure prediction strongly suggests the presence of two α-helices, one spanning residues 147–164 and one residues 171–185. This architecture is conserved among known homologues from other filamentus fungi, including Neosartorya, Penicillium, Ajellomyces, etc. The nudC gene is stringently conserved in all of Eukaryota, including protozoans (Trypanosoma, Chlorella, Chlamydomonas, etc), invertebrates (C. elegans, Drosophila, Anopheles, etc), plants (Populus, Ricinus, Zea, Arabidopsis, etc) and vertebrates (zebra fish, salmon, newt, African clawed frog, chicken, dog, mouse, human, etc). The only significant difference is that the N-terminus portion in higher eukaryotes is longer than in fungi. In plants (e.g. Zea mays) it is ~135 residues long, with pronounced propensity for a coiled-coil within the 60–130 fragment. Among Metazoans, it is 150–160 residues in length and the predicted coiled-coil element (60–135) is separated from the globular domain by a 20-residue linker. Interestingly, the most conserved elements are outside the globular domain; in vertebrates, a stretch from residue 10 through to 43 (human NudC numbering) is nearly fully conserved between a range of species, as is the C-terminal fragment downstream of the p23-like domain.

A homologous gene, coding for the NudCL protein, is so far identified only in the animal kingdom, and appears as low on the evolutionary ladder as in Platyhelminthes (flatworms), but is then found all the way up to humans. The sequence features of the NudCL protein, which is typically slightly longer that NudC, are very similar, except that the putative coiled-coil spans fewer residues (75–99). There is also strong conservation in the NudCL subfamily, and in vertebrates there are three nearly completely conserved fragments: one at the N-terminus (residues 10–58) and two within the predicted α-helices at the C-terminus. However, these fragments differ significantly between the NudC and NudCL subfamilies: there is only ~30% amino acid identity within the N-terminal fragment between human NudC and NudCL, and ~25% identity between the C-terminal α-helices in the two proteins.

The third of the nudC family of genes, the NudCL2-coding gene appears to be ubiquitous in all eukaryotes. It is different from both NudC and NudCL in that it lacks the entire N-terminal extension, while the C-terminal fragment downstream of the putative p23-like domain, about 50 residues in length, contains a single predicted α-helix (residues 110–130 in the human sequence). There is only limited amino acid similarity between the globular domain of NudCL2 and either NudC or NudCL, with 15–20% amino acid identity; the C-terminal portion including the predicted helix, which is stringently conserved with the NudCL2 subfamily, bears no resemblance to the corresponding fragments in either NudC or NudCL.

The fourth distant relative is the NudC-domain containing protein 1, NudCD1, which appears to be a product of gene shuffling. The protein is found throughout Metazoa, including Trichoplax adhaerens, the sole member of the phylum Placozoa, and the simplest known metazoan with only 11,514 protein coding genes53. Among vertebrates it is highly conserved, and occurs as two splicing variants, 583 and 554 amino acids in length. Aside from the NudC-like domain in the center of the polypeptide chain, the remainder of the sequence does not resemble any known protein family. However, we used 3DJury54,55 to predict the tertiary folds of the N- and C-terminal regions, and we obtained results strongly suggesting that both regions contain partial β-propeller folds. Based on these results it seems possible that NudC-like domain has been inserted into a split canonical seven-blade β-propeller. The functional consequences of this unusual architecture cannot be predicted. Because this protein is only distantly related to the three principal paralogues, it was not a subject of our experimental investigation.

Identifying the boundaries of folded globular domain in hNudC

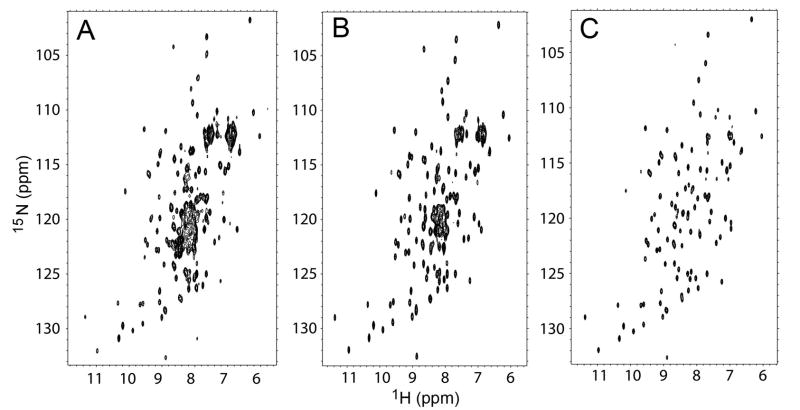

Although sequence analysis suggested that the globular domain in hNudC is limited to ~80 amino acids, a high level of sequence conservation extending into the C-terminus prompted us to investigate the actual structural boundaries of the globular domain using heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. Samples of 15N-labeled variants of different lengths were prepared and HSQC spectra were recorded (Fig. 2). The fragment encompassing residues 143–331 showed a significant number of poorly dispersed resonances, suggesting lack of secondary structure in a significant portion of the protein. Screening of variants with truncations at both ends ultimately yielded one variant encompassing residues 158–274, which showed a very well dispersed spectrum, with no indication of disorder. Further truncations (e.g. 162–274) were accompanied by chemical shift changes in the core resonances, suggesting structural rearrangements (data not shown), and were not pursued any further.

Figure 2.

NMR 2D HSQC spectra recorded for three different variants of hNudC: (A), hNudC143–331; (B) hNudC158–331; (C) hNudC158–274.

The crystal structure of the CS domain of hNudC

The wild-type recombinant 158–274 fragment did not yield single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction experiments. Therefore, we decided to apply the surface entropy reduction protocol 56–59 to obtain variants with enhanced crystallizability. Of the five variants tested, a double mutant E236A, K239A yielded good quality crystals and the structure was solved by MAD phasing using SeMet-labelled protein. The atomic model was refined using data extending to 1.75 Å resolution; the crystallographic details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data

| SeMet peak | Refinement | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Wavelength | 0.97928 | 0.97928 |

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell | a=66.73Å, b=51.82Å, c=92.85Å β=90.58° |

a=66.73Å, b=51.82Å, c=92.85Å β=90.58° |

| Resolution (Ǻ)* | 1.75(1.81-1.75) | 1.75(1.81-1.75) |

| No. of total reflections | 258,269 | 259,696 |

| No. of unique reflections | 124,203 | 63,806& |

| Redundancy | 2.1 (1.9) | 4.1(3.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (97.4) | 99.9(99.0) |

| Rsym (%) ** | 7.1 (38.0) | 9.9(41.2) |

| I/σ(I) | 11.9(2.2) | 12.0(3.1) |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Model composition | 5753 atoms (590 res + 877 waters+1 acetate ion) | |

| Resolution limits(Ǻ) | 28-1.75 | |

| Reflections in working/test sets | 60,523/3,227 | |

| Rcryst§/Rfree (%) | 17.3/20.2 | |

| Bond(Ǻ)/angle(°) | 0.006/1.03 | |

| r.m.s. deviation | ||

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Most favored regions | 457/90.7% | |

| Additional allowed regions | 47/9.3% | |

| Generously allowed regions | 0/0.0% | |

| Disallowed regions | 0/0.0% | |

| Average atomic B values protein/water (Å2) | 26.1/34.2 | |

The numbers in parentheses describe the relevant value for the last resolution shell

Rsym =Σ |Ii−<I>|/ΣI where Ii is the intensity of the ith observation and <I> is the mean intensity of the reflections;

Rcryst = Σ||Fobs| − |Fcalc||/Σ|Fobs|, crystallographic R factor, and Rfree = Σ||Fobs| − |Fcalc||/Σ|Fobs| where all

reflections belong to a test set of randomly selected data.

+/−reflections from the SeMet peak data set were scale together for the data set used in refinement

The asymmetric unit of the crystal contains five independent copies of the molecule. In each case there is interpretable electron density for all but the last 1–2 residues. The core of the molecule is formed by an all-antiparallel β-sandwich, with the larger sheet made up of strands 1,2,3,8,7 and the opposite, smaller sheet made up of strands 4,5,6. These strands are the only well defined secondary structure elements within the domain, with ~60 % of the residues occurring in loops, a 10-residue long N-terminal extension and a 29-residue long C-terminal fragment (Fig. 3a). All five copies superpose very well (with pair wise r.m.s. differences between Cα positions of 0.1 – 0.3 Å), indicating that this tertiary fold is not influenced by crystal-packing forces and faithfully represents the structure of the protein in solution.

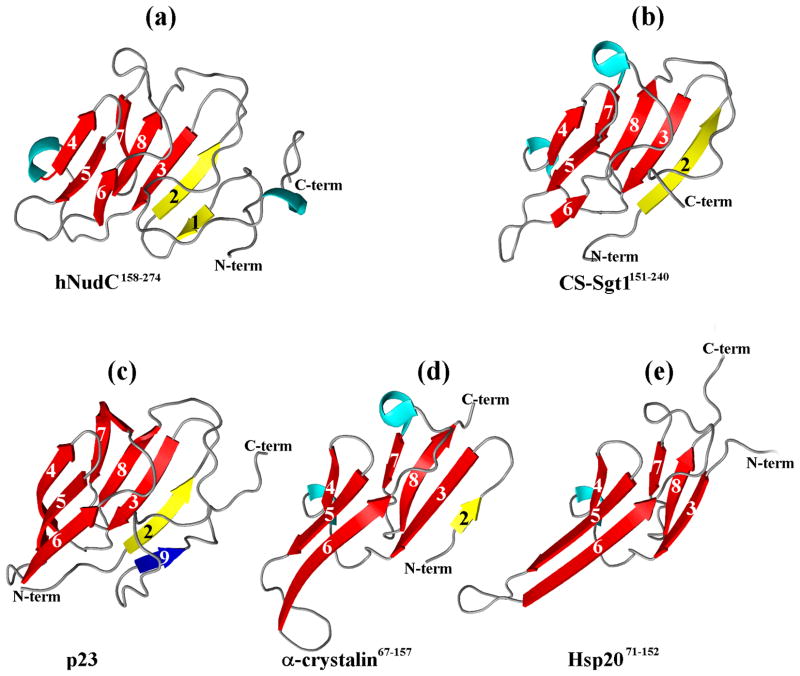

Figure 3.

A comparison of the crystal structure of the CS domain from hNudC, residues 158–274 (shown in A, this work, PDB code 3QOR) with those of (B) Sgt1 (PDB code 2XCM); (C) p23 (PDB code 1EJF); (D) α-crystallin (PDB code 2WJ7); (E) rat Hsp20 (PDB code 2WJ5)

In general terms, the core of the molecule shares the tertiary fold with the Hsp90 co-chaperone p23 60, the Hsp20 chaperone and α-crystallin core domains 61, although there are differences in the loop structures, as well as in the exact numbers and lengths of the β-strands (Fig. 3c, d and e). As indicated by DALI 62,63, the crystal structure of the hNudC core domain is most similar to the CS domain of the Arabidopsis thaliana Sgt1a protein (Z score of 11.4 and an r.m.s. deviation of 1.7Å) even though amino acid sequence identity is only 13% (Fig. 3b). The Sgt1 protein, found in fungi, plants and animals, is a co-chaperone of Hsp90, and appears to play an important role in innate immunity 64,65. Its 90-residue long CS domain is smaller than the core hNudC domain in that it lacks the N-terminal fragment including the first β-strand, while its C-terminal fragment is shorter.

There are also distinct similarities to the core domains of Sba1, another Hsp90 co-chaperone,66 and Shq1p, an essential H/ACA ribonucleoparticle assembly protein, whose function is unclear, although it is known to be Hsp90-independent 67.

While the Pfam database 68,69 classifies the Hsp20/α-crystallin proteins separately (Hsp20 or PF00011), all other sequences are grouped together as the CS (PF04969) family, which currently contains over 1,150 sequences. Among them is the functionally studied, but not structurally characterized, CS domain of the Siah1-interacting protein (SIP)70,71. We will refer henceforth to the core domains of all NudC proteins as CS domains.

The conserved C-terminal fragment of hNudC

Our initial NMR experiments strongly suggested that the C-terminal fragment of hNudC (i.e. downstream of residue 274) is not a part of the CS domain, even though it shows stringent amino acid sequence conservation within the entire NudC subfamily. This is unexpected, because typically such sequence conservation occurs within folded domains. Therefore, we decided to explore the question of the intrinsic structure of the C-terminus in more depth. In order to identify resonances corresponding to residues within the C-terminal fragment, we compared the HSQC spectra for hNudC158–331 and hNudC158–274 (Fig. 2b, c) and found 47 additional peaks for the longer construct, but with poor chemical shift dispersion. To ascertain whether the C-terminal fragment has any defined tertiary structure in solution, we measured 15N{1H} heteronuclear NOE’s for NudC158–331. Interestingly, the vast majority of residues in the C-terminal region show positive heteronuclear NOEs with an average value of 0.70 ± 0.16, which strongly indicates that this fragment adopts some ordered structure. Very limited chemical shift dispersion observed in the HSQC spectra is consistent with the presence of an α-helical structure, in agreement with secondary structure prediction. We then asked if the C-terminal fragment interacts with the CS domain. A comparison of HSQC spectra for hNudC158–331 and hNudC158–274 revealed that truncation of the C-terminus results in marginally small differences for the resonances within the CS-domain. This strongly indicates that there are no significant contacts between the C-terminal α-helical fragment and the CS-domain, and therefore the C-terminal α-helix is free to tumble independently in solution.

The structure of CS domains in other NudC family proteins

While this work was in progress, a search of the Protein Data Bank revealed several coordinate sets deposited for NudC family proteins by Structural Genomics Centers.

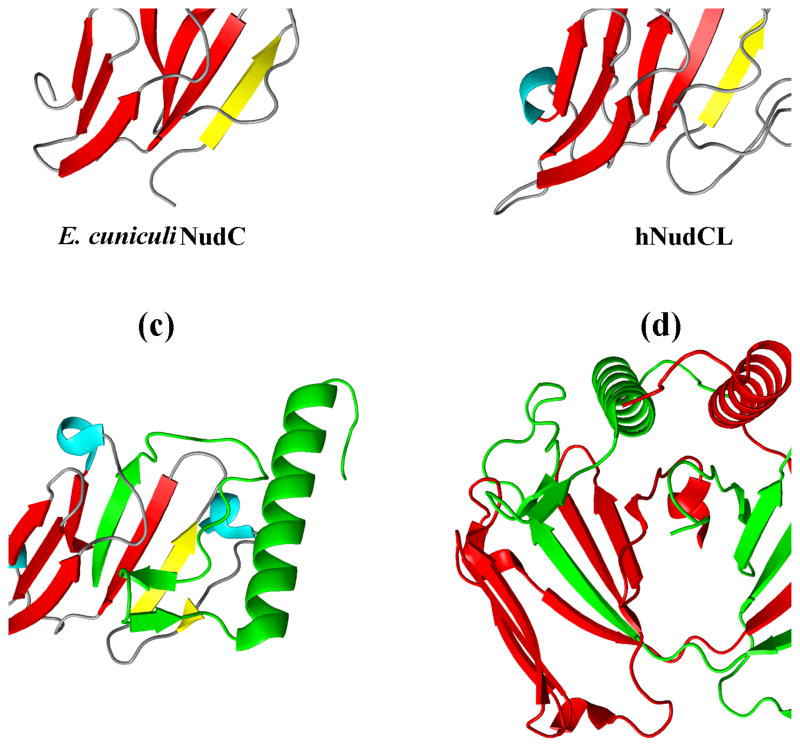

The crystal structure of the protozoan E. cuniculi NudC homologue (PDB entry 2O30) represents the shortest known NudC protein, essentially containing only the CS domain. A BLAST search shows that the sequence of this protein is most similar to plant homologues of NudC (39% amino acid identity to Zea mays), while among the human proteins it is most similar to hNudCL (29% identity). The CS domain of E. cuniculi NudC lacks the N-terminal first strand, and the loop structure makes it more similar to p23 (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

The structures of CS domains from various NudC family proteins; in all figures the core β-strands are shown in read, and the N-terminal strand in yellow: (A) The crystal structure of the CS domain from E. cuniculi (PDB entry 2O30; this structure was determined at 1.7 Å and refined to R/Rfree of 0.217 and 0.256 respectively); (B) NMR structure (best out of 20 conformers) of the 176–286 fragment of the CS domain from human NudCL (PDB 1WGV); (C) The crystal structure of the full length mouse NudCL2 (PDB 2RH0; resolution 1.95 Å, R/Rfree 0.192/0.235) – only one ‘monomer’ is shown; the red and green fragments originate from two different molecules in the asymmetric unit. (D) Complete, domain-swapped homodimer of NudCL2; the two molecules are depicted in red and green, respectively.

There is no crystal structure known of the CS domain from NudCL, but there are two solution (NMR) structures (PDB entries 1WGV and 2CR0) of fragments of the human and mouse proteins, respectively, which reveal a tertiary fold virtually identical, within experimental limits, to that seen in our crystal structure of the CS domain of hNudC (Fig. 4b).

The crystal structure of the full-length mouse NudCL2 (mNudCL2, PDB entry 2RH0) shows several unexpected features. The core of the CS domain appears deceptively similar to that of hNudC, except that downstream of the β8 strand, the last strand in the β-sandwich, there is a short antiparallel β-hairpin and a six-turn α-helix (Fig. 4c). Thus, unlike in NudC, the C-terminal fragment is a part of the globular entity. On closer inspection, the β8 strand and the downstream secondary structure elements originate from the neighboring monomer, creating a domain-swapped homodimer (Fig. 4d). The two C-terminal α-helices, one from each monomer, are aligned in this dimer in an antiparallel fashion and form a part of an intimate dimer interface.

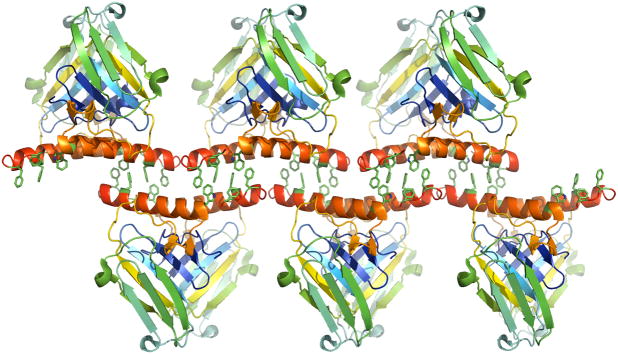

An intriguing aspect of the mNudCL2 crystal structure is the assembly of the dimers into a filament, by virtue of a non-crystallographic two-fold screw axis, which is parallel to the crystallographic a axis (Fig. 5). This filament is formed exclusively by the exposed faces of the two antiparallel α-helices, unique to NudCL2, which at each end contain a cluster of solvent exposed hydrophobic residues: Trp113, Phe127, Phe134, Phe136 (nearly 1,100 Å2 per dimer). The clusters from one dimer interlock with the dimers shifted in each direction by half a molecule’s length. The interface-forming, exposed hydrophobic residues in the C-terminal helix are among the most conserved amino acids in the known NudCL2 amino acid sequences. This strongly suggests that the surface patch mediating this crystal contact may be biologically relevant, and may be involved in hitherto unidentified protein-protein interactions.

Figure 5.

The principle crystal contacts in the NudCL2 structure showing the assembly of the homodimers into a filament via a conserved hydrophobic surface. The side chains of Trp113, Phe127, Phe134, and Phe136 are shown in detail, but not labeled.

Oligomeric state of the NudC family proteins

Although the crystal structure of hNudC CS domain contains five copies in the asymmetric unit, there is no indication that these molecules form specific oligomeric structures in solution, as is the case, for example, for the Hsp20/α-crystallin proteins 72. Moreover, the CS domain of hNudC as well as the hNudC158–331 variant, which includes the C-terminal α-helix, are both distinctly monomeric in solution, as determined by gel filtration and judged by the NMR line widths (data not shown). In contrast, full-length hNudC migrates on gel filtration with an apparent molecular weight of ~140 kDa (not shown), suggesting that it forms an oligomer. In view of the putative coiled-coil within the N-terminal fragment of the mammalian NudC sequences, we wondered if this motif was responsible for protein oligomerization. We expressed the fragment comprising residues 1–141, and using gel filtration determined that it had an apparent molecular weight of ~62 kDa (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Given that coiled-coils migrate faster and typically show near double the actual molecular weight, our result was consistent with NudC1–141 forming a homodimer. To evaluate if the fragment contains a coiled-coil structure, we used circular dichroism (CD) spectropolarimetry, and analyzed the ratio of ellipticities at 222/208 nm. We determined that the 1–141 fragment contains a stretch of approximately 50 amino acids that form a coiled–coil structure, with the remainder forming random coil (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Theoretical coiled-coil prediction 73 suggests that the sequence between residues 50 – 135 has a propensity to form a coiled-coil, but with a discontinuity at Pro102. We conclude that NudC is a dimer, with the coiled-coil motif (most likely parallel and encompassing amino acids 50 – 100) mediating dimerization.

We also evaluated the molecular weights of hNudCL and mNudCL2 in solution using gel filtration. Both proteins behaved as dimers (not shown). Given sequence similarities between the two proteins as well as structure prediction, we hypothesize that dimerization in the NudCL subfamily is mediated by its N-terminal coiled-coil motif, in a manner analogous to hNudC. In the case of NudCL2, our data are consistent with the crystal structure and suggest that dimerization occurs through domain swapping.

Chaperone activity of the mammalian NudC proteins

The structures of the CS domains in the NudC family bear distinct similarity to those found in small heat shock chaperones, such as p23 and Hsp20, suggesting that NudC proteins may play a similar role in eukaryotic physiology. It should be noted here that some of CS-domain containing proteins have been shown to function as Hsp90 co-chaperones, but may also show intrinsic chaperone activity independent of Hsp90. Interestingly, experimental evidence has been published supporting both such functions for the NudC family. Specifically, the C. elegans NudC homolog, NUD-1, has been shown to exhibit chaperone activity in vitro, preventing the aggregation of citrate synthase and luciferase 44. Human NudC has been implicated in Hsp90 mediated pathways, resulting in stabilization of Lis1, and was shown to have intrinsic chaperone activity in vitro, preventing aggregation of citrate synthase 40. Similar observations, i.e. interaction with Hsp90 and Lis1 stabilization, were reported for NudCL2, although it was not established if this paralogue has in vitro chaperone activity 26. The human NudCL was implicated in the stabilization of the dynein intermediate chain, through an unknown mechanism 74. Finally, the Arabidopsis thaliana homologue of NudC, BOBBER1, was shown to be a heat-shock protein by preventing thermal aggregation of malate dehydrogenase (MDH); it is also required for development and thermotolerance 75. In view of these results, we decided to reassess the in vitro chaperone activities of all three mammalian NudC family members, by monitoring aggregation of luciferase and citrate synthase using light scattering.

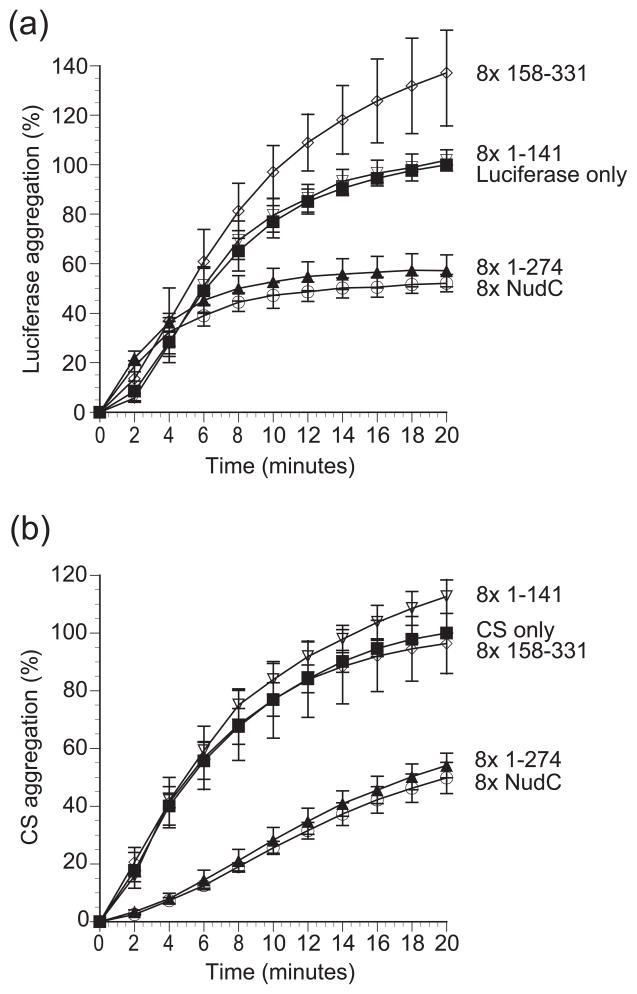

As expected, full-length hNudC clearly displayed chaperone activity and suppressed aggregation of both luciferase and citrate synthase at ~50% level (Fig. 6). We then took advantage of our knowledge of the structure of hNudC to investigate what structural requirements are necessary for the observed activity. To that end we tested several hNudC variants including hNudC 1–274, which lacks only the unstructured C-terminal tail; hNudC 158–274, i.e. the isolated CS domain; hNudC 158–331, comprising the CS domain and the C-terminal tail; and hNudC 1–141, which constitutes the dimerization domain. The hNudC 1–274 variant exhibited chaperone activity similar to the wild-type protein. In contrast, the isolated hNudC CS domain (hNudC 158–274), hNudC 158–331 and hNudC 1-–141 were unable to suppress aggregation of any of the two substrates (Fig. 6 and data not shown). Thus, it appears that dimerization, but not the C-terminal conserved tail, is essential for the chaperone activity.

Figure 6.

Dimerization is required for the chaperone activity of NudC. (A) Luciferase (0.1 μM, filled squares) was incubated at 42° C for 20 minutes in the presence and absence of 0.8 μM NudC (open circles), construct 1–274 (filled triangles), construct 158–331 (open diamonds), and construct 1–141 (open inverted triangles). Aggregation was measured by light scattering at 370 nm. Data represents the average of 3 independent trials and are expressed as a percentage of maximum aggregation of luciferase at 20 minutes with ± mean standard deviation. (B) CS (0.15 μM, filled squares) was incubated at 44 °C for 20 minutes in the presence and absence of 1.2 μM NudC (open circles), construct 1–274 (filled triangles), construct 158–331(open diamonds), and construct 1–141 (open inverted triangles). Aggregation was measured and calculated as described in A. All NudC concentrations were based off the monomeric form.

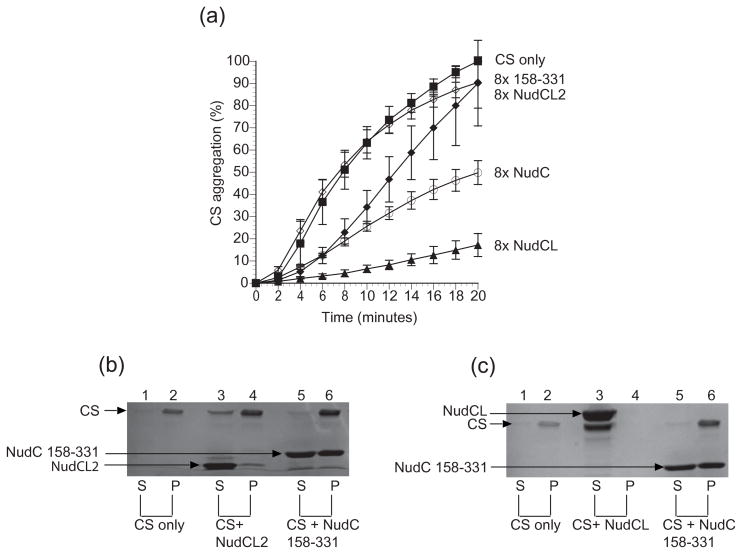

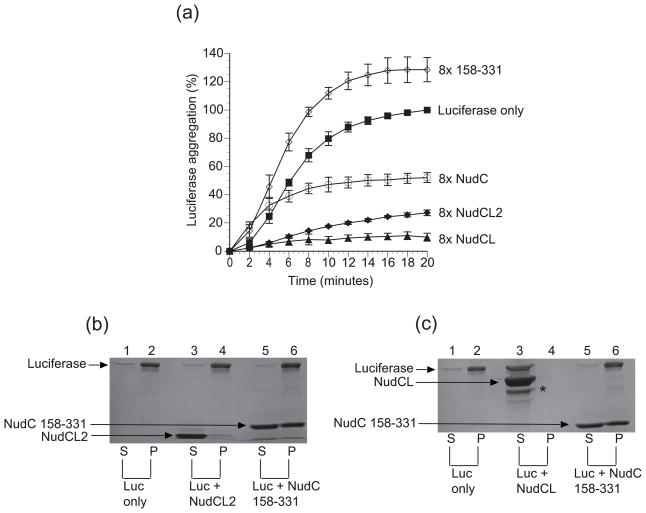

Next, we investigated if analogous intrinsic chaperone activity could be detected for hNudCL and mNudCL2 (Fig. 7 and 8). As expected, hNudCL displayed such activity, resulting in essentially complete suppression of aggregation for both protein targets using the same molar concentration as hNudC. In contrast, mNudCL2 displayed inconsistent results, suppressing ~70% of luciferase aggregation, but with no impact on aggregation of citrate synthase. Because of this substrate discrepancy, we decided to use SDS-PAGE as a secondary readout to monitor the aggregation of luciferase and citrate synthase, after incubation of these proteins with target chaperones76. This assay allows for the quantification of the suppression of protein precipitation, but not for the detection of soluble aggregates. Addition of mNudCL2 resulted in a small increase of concentration of citrate synthase in the supernatant compared with the control, while luciferase was found exclusively in the pellet fraction. In contrast, and in agreement with the light scattering data, hNudCL completely suppressed aggregation of both luciferase and citrate synthase, with both proteins found after incubation exclusively in the supernatant.

Figure 7.

Suppression of luciferase aggregation by NudC proteins. (A) Luciferase (0.1 μM, filled squares) was incubated at 42°C in the presence and absence of 0.8 μM NudC (open circles), NudCL (filled triangles), NudCL2 (closed diamonds) and the negative control, NudC construct 158–331 (open diamonds). Data represent the average of 3 independent trials and are expressed as a percentage of maximum aggregation of luciferase at 20 minutes with ± mean standard deviation. (B) Lanes 1,3, and 5 represent the soluble fractions. Lanes 2, 4, and 6 are the insoluble fractions. Lanes 1 and 2 consist of 0.82 μM luciferase by itself. Lanes 3 and 4 consist of 6.56 μM NudCL2 with 0.82 μM luciferase. Lanes 5 and 6 represent the negative control, 6.56 μM NudC construct 158–331 and 0.82 μM luciferase. (c) Lanes 1,3 and 5 represent the soluble fractions and lanes 2,4, and 6 represent the insoluble fractions. Lanes 1 and 2 consist of 0.82 μM luciferase only. Lanes 3 and 4 include 6.56 μM NudCL with 0.82 μM luciferase. Lanes 5 and 6 contain 6.56 μM NudC construct 158–331 and 0.82 μM luciferase. The asterisk represents a degradation product of NudCL. All NudC concentrations assume a monomeric state.

Figure 8.

Suppression of CS aggregation by NudC proteins. (A) CS (0.15 μM, filled squares) was incubated at 44 °C in the presence and absence of 1.2 μM NudC (open circles), NudCL2 (closed diamonds), NudCL (filled triangles), and the negative control NudC construct 158–331 (open diamonds). Data represent the average of 3 independent trials and are expressed as a percentage of maximum aggregation of citrate synthase at 20 minutes with ± mean standard deviation. (B) Lanes 1, 3, and 5 represent the soluble fractions. Lanes 2, 4, and 6 are the insoluble fractions. Lanes 1 and 2 consist of 1.6 μM citrate synthase by itself. Lanes 3 and 4 consist of 12.8 μM NudCL2 with 1.6 μM citrate synthase. Lanes 5 and 6 represent the negative control, 12.8 μM NudC construct 158–331 and 1.6 μM citrate synthase. (C) Lanes 1,3 and 5 represent the soluble fractions and lanes 2,4, and 6 represent the insoluble fractions. Lanes 1 and 2 consist of 1.6 uM citrate synthase only. Lanes 3 and 4 include 12.8 μM NudCL with 1.6 μM citrate synthase. Lanes 5 and 6 contain 12.8 μM NudC construct 158–331 and 1.6 μM citrate synthase. All NudC concentrations assumed a monomeric state.

Finally, we used a third well known chaperone substrate, malate dehydrogenase (MDH)77, and monitored the aggregation by SDS-PAGE (Supplemental Fig. 3). As before, hNudCL completely suppressed aggregation of MDH resulting in its localization solely to the soluble supernatant fraction. Neither mNudCL2 nor the negative control hNudC158–331 suppressed aggregation. True chaperones are capable of recognizing and interacting with a broad range of non-native misfolded protein, rather than only specific ones78,79 In this regard, hNudC and hNudCL both act consistently as molecular chaperones in suppressing protein aggregation across multiple substrates. Although it could be argued that the ability of NudC and NudL to suppress protein aggregation in vitro may be due to nonspecific interactions with misfolded substrates, we find this unlikely as several labs now have reported chaperone activity for quite a few different NudC homologs using various chaperone assays with a variety of misfolded substrates40,44,75. These assays are well-established for classifying small heat shock chaperones80–82. The mNudCL2 protein, however, behaves differently, exhibiting only some activity in the luciferase assay, and even then the results were not reproducible across multiple substrate readouts.

Many proteins act as chaperones in suppressing protein aggregation of misfolded substrates but also perform other functions. For example, calreticulin, torsinA, and Hsp90 are involved in nuclear export, maintaining nuclear envelope cytoskeletal structure, and cargo loading of dynein, respectively, but all have chaperone-like activities 83–87. The physiological role of NudC chaperone activity has yet to be elucidated; prior studies have suggested a possible role in protein stabilization, as the absence of NudCL or NudC results in dynein light chain aggregation or lower levels of NudF, respectively18,25. Thus, it is possible that NudC and NudCL might be interacting with certain members of the Lis1/Dynein complex for stabilization. Regardless, future studies are needed to confirm the role of NudC chaperone activity as it relates to its normal cellular function.

NudC proteins do not interact with Lis1 in vitro

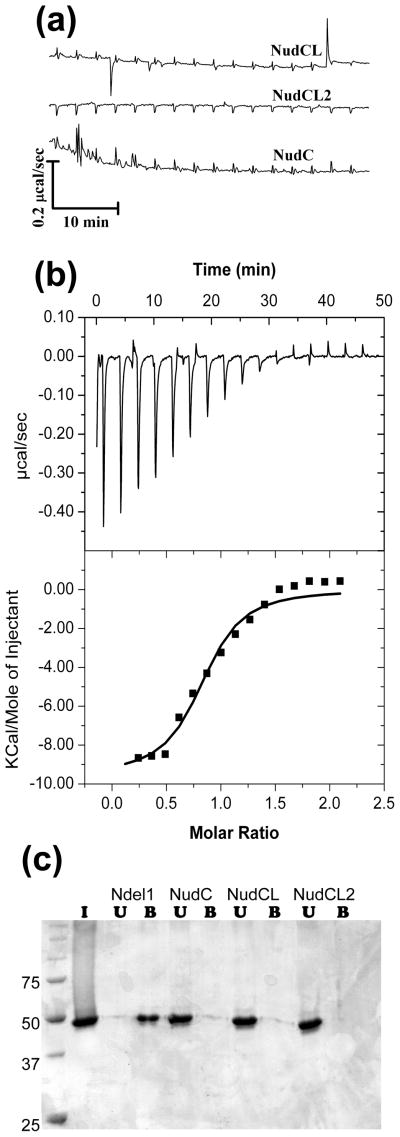

CS domains appear to occur predominantly in proteins with chaperone or co-chaperone activities, or proteins that recruit Hsp90 to regulate macromolecular assemblies. It is therefore surprising that the mammalian NudC proteins have been implicated in direct interactions with Lis1, a WD40 family member, which has no relationship to any chaperones 19,39,41. Given this apparent inconsistency, we decided to re-evaluate if such binary interactions can be observed in vitro. We used bacterially expressed NudC proteins, and sf9-expressed human Lis1, both of which are folded correctly as shown by biophysical and crystallographic studies11. As a positive control we used recombinant Ndel1 58–169 which is well documented to bind Lis1 with a dissociation constant (KD) of ~0.3 μM 11,16. In isothermal calorimetric titration (ITC) experiments we were easily able to reproduce the Lis1-Ndel1 interactions, while none of the three NudC proteins appeared to interact with Lis1, as inferred from lack of enthalpy change (Fig. 9a). Because ITC experiments detect only enthalpy changes and entropy-driven effects may be overlooked, we also conducted canonical pull-down experiments. They confirmed that NudC proteins do not form binary complexes with Lis1 (Fig. 9b).

Figure 9.

The NudC proteins do not form binary complexes with Lis1. (A) Raw calorimetric titration data for the thee NudC proteins titrated against Lis1 (see methods), showing no enthalpy change. (B) Positive control showing the titration curve of Lis1 against Ndel1, a known partner of Lis1. An ITC profile of the interaction of Ndel1 with Lis1 is shown in upper panel and individual dissipated heats plotted against the molar ratio of interacting proteins in the lower panel. The data were fitted with “one set of sites model” shown as a solid line on lower panel. The best fit resulted in Ka=6.4×105 M−1, n=0.83 and ΔH=−9.5 kcal/mol of dimer. (C) Pull-down experiments showing binary interaction of Lis1 with Ndel1 (see methods), and no interaction with any of the NudC proteins. I, input; U, unbound, i.e. flowthrough; B, bound.

Concluding remarks

The biological importance of the NudC family of proteins is undisputed. The high level of amino acid conservation in each of the three subfamilies and the ubiquitous presence of the proteins in all tissues and cells examined both during development and in adult life, are all consistent with a critical function that these proteins play in cell physiology, most probably in mitotic cell division and proliferation. However, the precise mechanism by which these proteins function is not known. Two hypotheses were particularly intriguing. First, the genetic link to the fungal NudC and therefore to other proteins of the Nud family strongly suggested a functional coupling to dynein regulation. This has inspired a number of investigators to look at direct interactions of NudC with Lis119,39,41. Second, the expected similarity of the NudC globular domain to the CS domain of p23 and Hsp20, suggested an alternative role for NudC family members, as chaperones and/or co-chaperones. In this paper we explored both these possibilities, through the analysis of structural features of NudC itself, NudCL and NudCL2, their ability to bind Lis1 in vitro, and their performance in in vitro chaperone assays.

First, it is important to note that both NudC and NudCL share the overall molecular architecture. They are homodimeric proteins with a modular structure: a coiled-coil motif stretching over a ~50–70 residue long fragment in the N-terminal section constitutes the dimerization module, followed by a flexible linker, a CS domain, and finally two highly conserved α-helices separated by a short loop, which do not seem to interact with the CS domain. This conserved architecture of the two proteins suggests possible functional redundancy, although amino acid sequence identity between the two is relatively low. It is important to realize that these molecules are obligate dimers, and biological function may well be dependent on dimerization. Thus, studies of isolated fragments, such as CS domains alone, are prone to misinterpretation, if the oligomeric structure is not taken into account. A particularly intriguing feature of both NudC and NudCL is the C-terminal α-helical element. An extremely high amino acid sequence conservation of this fragment suggests that this is a very specific targeting module which interacts with an as yet unidentified protein. There are other examples of similar architecture where a stable helix, not otherwise associated with a tertiary domain, is essential for the formation of a binary complex. One such example is the human Rho GTPase guanine dissociation inhibitor (Rho GDI), which contains a globular domain and two flexible α-helices, which do not interact with the former, but which attain an ordered structure only in complex with the target Rho GTPase88,89. However, it is possible that this element can only function within a homodimeric ensemble.

The NudCL2 protein is a good example of the danger of misinterpretations based on sequence analysis alone. While the sequence suggests that this protein is similar to NudC/NudCL, albeit without the N-terminal dimerization module and the linker, the crystal structure reveals a different story: the protein is also an obligate dimer, but the dimerization occurs due to domain swapping involving the last β-strand and the C-terminal helix, rather than an element extraneous to the CS domain. Again, this architecture must be taken into account when one designs mutants and deletion variants for functional studies. For example, dissecting NudCL2 into fragments, to assess their binding abilities, most likely destroys the protein’s integrity and results in unfolded denatured fragments.

The crystal structures cannot reveal precise cellular functions, but can provide useful hints. The presence of CS domains in all NudC homologues is consistent with a chaperone or co-chaperone role. Such domains, while ubiquitous, have not been shown to be involved in any signaling events via specific protein-protein interactions.

Intrinsic in vitro chaperone activity has been reported for the C. elegans NudC homologue44 and for the human NudC40, and chaperone or co-chaperone functions have been suggested for both NudCL and NudCL225,26. We were able to confirm that both NudC and NudCL, but not NudCL2, are able to suppress aggregation of a range of protein targets in vitro, and we find that the chaperone activities are dependent on the dimeric architecture of these proteins, but not on the presence of the highly conserved C-terminal fragment. It is therefore surprising that a L279P mutant of hNudC, where the mutation is located within the C-terminal fragment, was recently reported to lower the chaperone activity40. One possible explanation is that the mutated C-terminus somehow interferes with the remainder of the protein. It is also important to note that the dimeric structures of NudC and NudCL do not exclude the possibility that these proteins may interact with Hsp90 via the CS domain and/or C-terminal helices.

In contrast, the NudCL2 protein presents a very different picture. It is unlikely to function in the same way as NudC or NudCL, because of its different molecular architecture. However, the conserved, solvent exposed hydrophobic surface which includes Trp113, Phe127, Phe134, Phe136 contacts strongly suggests potential for protein-protein interactions. Further, it is able to form filaments in the crystal structure, indicating that it may form low-affinity polymers, or indeed interact with unstable or unfolded proteins in a fashion similar to chaperones.

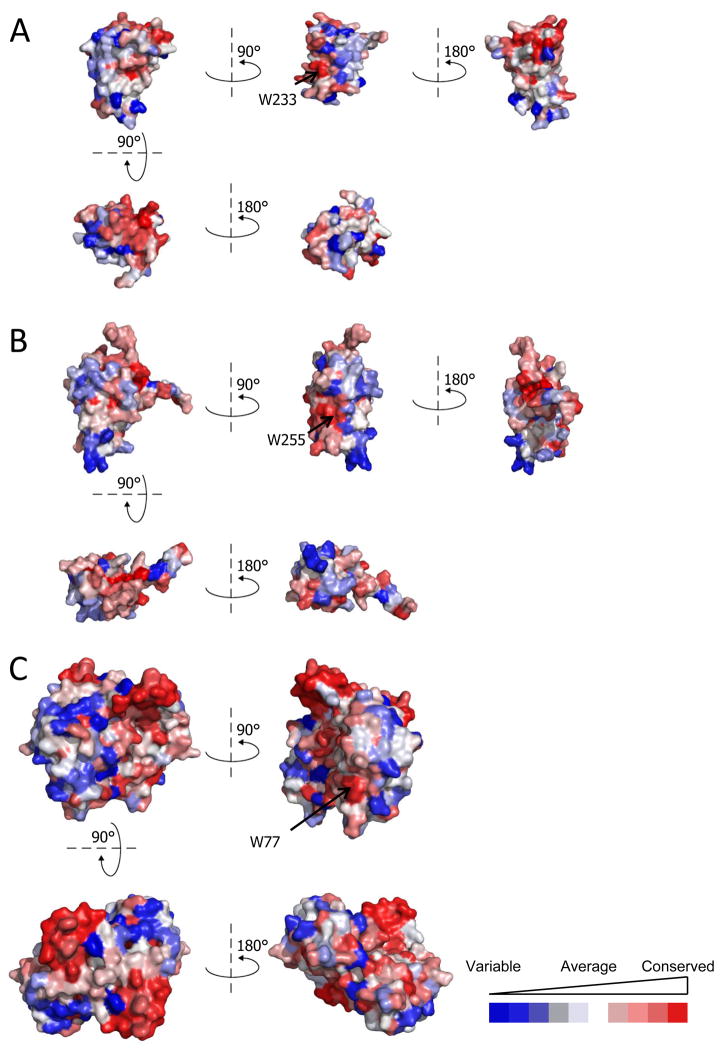

The molecular mechanisms of intrinsic chaperones are often elusive because it is difficult to identify the functional surfaces. Given that all three NudC subfamilies may function as chaperones, we wondered if surface sequence conservation might reveal some clues as to teh mechanism. Interestingly (Fig. 10), we found that each subfamily contains some conserved patches, with one in the same topological location in all three. This patch contains a single amino acid that is solvent exposed and completely conserved throughout all NudC proteins: Trp233 (NudC), Trp255 (NudCL) and Trp77 (NudCL2). Further work will be necessary to clarify if this pattern of evolutionary conservation is related to functional properties.

Figure 10.

Sequence conservation calculated as described in Methods was mapped onto (A) hNudC, (B) mNudCL, and (C) mNudCL2 (dimer) protein surfaces. The level of conservation is depicted on a colour scale - from blue (least conserved) to red (most conserved). The mNudCL structure and chain A of mNudCL2 were aligned to hNudC and rotated as indicated. The only fully invariant amino acid, based on sequence alignment and topology, is a tryptophan, in each case indicated by an arrow.

Finally, we tested if the NudC proteins bind Lis1. We took advantage of structural information and we used insect-cell derived Lis1, known to fold properly, as well as full-length, homodimeric forms of recombinant NudC, NudCL and NudCL2 proteins. Using both ITC and pull-down assays we show conclusively that no binary complexes are formed by any of these proteins with Lis1. We also tested if NudC interacts with the Lis1/Ndel1 complex – and obtained equally negative data (not shown). The original observation of NudC-Lis1 interaction was based on a yeast two-hybrid screen and a pull-down assay, using a GST-NudC fusion as bait, and rat Nb2 T cell extracts 39. It was further shown that NudC and Lis1 co-localize and can be detected using co-immunoprecipitation 39,41. Similarly, the fungal (Aspergillus) NudF protein was identified as NudC interactor through the yeast two-hybrid system19. None of these studies involved a rigorous biophysical assay of binary interaction using recombinant proteins that were shown to be properly folded. It is possible that one and more of NudC family members associate in the cell with larger complexes containing Lis1, or that the interaction is mediated by as yet uncharacterized protein, but based on our experimental data direct binding is very unlikely.

The structural characterization of the NudC family will help in further elucidation of their cellular functions.

Materials and Methods

Clones, protein expression and purification

The human nudC clone was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The expression vectors were constructed using Gateway™ (Invitrogen) technology and two templates, i.e. pDESTHisMBP containing a His6-tagged maltose binding protein (MBP), and pDEST15, containing a glutathione S-transferase (GST) as the N-terminus fusion tag. The fusion tag was followed by the TEV cleavage site, and a Ser4 spacer to improve proteolytic digestion. The vectors used were pDESTHisMBP-1 (NudC1–331), pDESTHisMBP-2 (NudC143–331), pDESTHisMBP-3 (NudC158–331), pDESTHisMBP-4 (NudC158–274) and pDESTHisMBP-5(NudC162–274), as well as pDEST15-6(NudC1–141), pDEST15-7(NudC56–141) and pDEST15-8 (NudC1–331).

An expression-ready construct, encoding a full-length mouse NudCL2 preceded by an expression-purification tag MGSDKIHHHHHH and a TEV cleavage site, was kindly provided by the Joint Center for Structural Genomics. The human NudCL and Lis1 were amplified by Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs) using reversely transcribed total human reference RNA (Clontech) as a template for PCR. The obtained cDNA fragments were cloned into a pHisParallel vectors, containing a His6-tag and a TEV cleavage site90. The Ndel58–167 was amplified from full-length cDNA16 and also cloned into a pHisParallel vector.

All hNudC variants and hNudCL were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) RIPL (Stratagene, Inc.) using routine protocols with minor variations. Briefly, expression was carried out in terrific broth (TB) with ampicillin and chloramphenicol, following induction at 37°C with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), for 16 h at 18 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by sonication. All proteins were purified using standard Ni-NTA or GST affinity chromatography. Recombinant TEV was used to cleave the His6-MBP, GST, or His6 tag, followed by gel filtration. Pure protein fractions were pooled together and concentrated to ~5–15 mg/ml for use in NMR analysis, biophysical studies and crystallization. The mNudCL2 protein was expressed and purified in a similar manner, except that BL21 cells were used and the expression was induced by the addition of L-arabinose to a final concentration of 0.3%.

To generate the selenomethionine- (SeMet-) labeled hNudC samples, the variants were expressed in E. coli B834 cells using the autoinduction medium containing SeMet. The cultures were grown for 4.5 h at 37 °C, followed by ~16 h at 20 °C and another 24 h at 10 °C. The proteins were purified as described above.

Human Lis1 was expressed in Sf9 cells and purified to homogeneity as described previously11. The rat Ndel1 fragment encompassing residues 58–167 was expressed in E. coli and purified as described elsewhere16

Crystallography

Because wild type NudC158–274 did not yield X-ray quality crystals, we designed five variants: K227A, E229A, E230A; K267A, K268A; K250A, E252A; E236A, K239A and K194A, K196A. The proteins were expressed and purified as described above. The wild type and mutant proteins were screened using the Wizard II crystallization matrix from Emerald Biosystems using reservoirs containing the screen solution. The double mutant E236A, E239A yielded diffraction-quality crystals from 25% PEG 3350, Na(CH3COO) pH 4.5, 0.1 M LiSO4 and crystallization of SeMet labeled samples was optimized starting from these conditions. A SAD data collection at Se absorption peak wavelength of 0.97928 Å was carried out at SER-CAT 22-ID beamline at Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, Chicago, USA). Data were processed and scaled using HKL2000 69. The crystals assumed monoclinic P21 symmetry with a unit cell of a = 66.7 Å, b = 51.8 Å, c = 92.9 Å and β = 90.6. The positions of Se atoms were obtained using SHELXD 91. Experimental phases of the anomalous substructure were refined using SHELXE 92.

The model was built automatically using ARP/wARP 93 which built 527 out of 580 residues. Crystallographic refinement was completed using Refmac5 94 from the CCP4 suite and Phenix 95 using. Programs ‘O’ 96 and Coot 97 were used for model display and manual model improvement. The refinement converged to an R factor of 17.2% with R free of 20.6%. The final model contains 5 copies of NudC molecule residues 158–274. Serine residue 274 in chains C and D are not well ordered and therefore were removed from the final model. All copies of the molecule contain extra electron density for serine amino acids that were inserted into the plasmid between the cloning sites for NudC and TEV proteinase for faster cleavage during the protein purification. For structure validation we used MolProbity 98 and Procheck99.

Surface sequence conservation

Surface sequence conservation was analyzed using Consurf 100,101. Homologues were automatically chosen from UniRef90 database using default parameters and aligned with MAFFT-L-INS-i algorithm.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

To produce 15N labeled samples, the respective variants were expressed in minimal media with (15NH4)2SO4 as sole source of nitrogen. The media were enhanced by the addition of labeled BioExpress (Cambridge Isotope Labs). Samples were purified using the procedure described above for wild-type proteins. NMR spectra for various CS-domain constructs were collected using Varian Inova 500 MHz spectrometer at 25 ºC. The NMR samples containing 15N-labeled hNudC fragments 143–331, 158–331, 158–274 and 162–274, were prepared in TRIS buffer, pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl. The HSQC and 15N{1H} heteronuclear NOE experiments for hNudC158–331 were also collected using Bruker Avance III 800 MHz spectrometer at 25 ºC. For the analysis of hNudC56–141 we conducted HSQC and 15N{1H} heteronuclear NOE experiments using Varian Inova 500 MHz spectrometer at 25°C. For these experiments, 1 mM 15N-labeled protein sample was prepared in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, 50 mM NaCl.

Analytical gel filtration

Analytical gel filtration was carried out using superdext 7510/300 GL(GE Healthcare) for determining the size and molecular weight of NudC proteins. By comparing its elution volume with those of known protein standards, NudC molecular weight was determined. The standard proteins used for size determination include albumin (MW, 67kD), ovalbumin (Chicken) (44 kD) chymotrypsinogen A (25kD) and ribonuclease A (13.7kD).

CD spectropolarimetry

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded on an AVIV Model 215 CD spectropolarimeter (AVIV Instruments, Lakewood, NJ) equipped with a thermoelectric temperature control. Data were recorded from 190 to 260 nm in benign buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0), and in buffer diluted 1:1 (v/v) with trifluoroethanol (TFE).

Chaperone assays

Citrate synthase (CS) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) were obtained from Sigma; Luciferase was purchased from Promega. Measurement of CS and luciferase aggregation was performed as described previously 44. Briefly, CS or luciferase were heated for 20 minutes in the presence and absence of full length NudC or its constructs and light scattering was measured with excitation and emission at 370nm with a 2.5 nm slit width on a PerkinElmer LS55 spectrofluorometer. The aggregation of luciferase, citrate synthase, and malate dehydrogenase was detected by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining as previously reported 76 by incubating luciferase, citrate synthase, or malate dehydrogenase for 1 h in the presence and absence of NudCL, NudCL2, or the negative control NudC 158–331. Reactions were then spun down in a microcentrifuge at 13,000 rpm to separate the insoluble pellet from the soluble fraction. The pellet was then resuspended in a volume equal to the supernatant and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie staining.

Pull-down experiments

The three NudC-family proteins and Ndel158–167 were each dialyzed against a solution containing 0.1 M NaHCO3 and 0.5 M NaCl, and were covalently linked to CNBr-activated Sepharose (BioRad) according to manufacturer’s instructions using 5 mg of protein per ml of Sepharose. Lis1 was dialyzed against the buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM, NaCl and 5 mM mercaptoethanol and diluted with the same buffer to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. 250 μl of Lis1 were added to 50 μl of Sepharose with covalently immobilized NudC proteins or Ndel1 and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Unbound fraction was recovered, beads were washed 3 times and boiled in sample buffer to release bound Lis1. Bound and unbound fractions were analyzed on Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was performed at 25 °C using a Microcal ITC-200 calorimeter (MicroCal, Northhampton, MA). Protein samples were dialyzed against a buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol prior to the experiment. Contents of the sample cell were stirred continuously at 300 rpm during the experiment. A typical titration of Lis1 involved 18–20 injections of the Ndel1 or one of the NudC-family proteins (0.3–0.9 mM, 2 μl, 3 minute intervals) into a sample cell containing 0.2 ml of Lis1 (70–110 μM). The baseline-corrected data were analyzed with Microcal Origin 5.0 software to determine the enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (S) association constant (Ka) and stoichiometry of binding (N) by fitting to the association model for a single set of identical sites.

Supplementary Material

Amino acid sequence alignments of proteins within the NudC family: (A) CS domain sequence alignement for the four human proteins, i.e. NudC, NudCL, NudCL2 and NudC-domain containing protein 1; (B)

Characterization of the coiled-coil fragment; (A) Analytical gel filtration of the hNudC1–141 fragment; (B) Circular-dichroism (CD) spectra of hNudC1–141 and hNudC56–141 fragments recorded in benign buffer and in the presence of 50% trifluoroethanol (TFE).

Suppression of malate dehydrogenase (MDH) aggregation by NudCL2 and NudCL by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. (A) Lanes 1, 3, and 5 represent the soluble fractions. Lanes 2, 4, and 6 are the insoluble fractions. Lanes 1 and 2 consist of 0.8 μM MDH by itself. Lanes 3 and 4 consist of 6.4 μM NudCL2 with 0.8uM MDH. Lanes 5 and 6 represent the negative control, 6.4 μM NudC construct 158–331 and 0.8uM MDH. (B) Lanes 1,3 and 5 represent the soluble fractions and lanes 2,4, and 6 represent the insoluble fractions. Lanes 1 and 2 consist of 0.8 μM MDH only. Lanes 3 and 4 include 6.4 μM NudCL with 0.8 μM MDH. Lanes 5 and 6 contain 6.4 μM NudC construct 158–331 and 0.8 μM MDH. Asterisk represents NudCL degradation product. All NudC concentrations assumed monomeric state.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NS036267) to ZSD. We thank Ms. Natalya Olekhnovich for technical assistance and Dr Jeff Elena for assistance with NMR experiments. The use of Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. Supporting institutions of SER-CAT may be found at http://www.ser-cat.org/members.html.

Footnotes

Accession numbers: The atomic coordinates and structure factors for the hNudC CS domain structure have been deposited with the PDB accession number 3QOR.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Morris NR. Mitotic mutants of Aspergillus nidulans. Genet Res. 1975;26:237–54. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300016049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiang X, Beckwith SM, Morris NR. Cytoplasmic dynein is involved in nuclear migration in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2100–2104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiang X, Osmani AH, Osmani SA, Xin M, Morris NR. NudF, a nuclear migration gene in Aspergillus nidulans is similar to the human LIS-1 gene required for neuronal migration. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:297–310. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willins DA, Xiang X, Morris NR. An alpha tubulin mutation suppresses nuclear migration mutations in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 1995;141:1287–98. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.4.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris NR, Xiang X, Beckwith SM. Nuclear migration advances in fungi. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:278–82. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckwith SM, Roghi CH, Morris NR. The genetics of nuclear migration in fungi. Genet Eng (N Y) 1995;17:165–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones KL, Gilbert EF, Kaveggia EG, Opitz JM. The MIller-Dieker syndrome. Pediatrics. 1980;66:277–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiner O, Carrozzon R, Shen Y, Wehnert M, Faustinella F, Dobyns WB, Caskey CT, Ledbetter DH. Isolation of a Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene containing G-protein β-subunits-like repeats. Nature (London) 1993;364:717–721. doi: 10.1038/364717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hattori M, Adachi H, Tsujimoto M, Arai H, Inoue K. Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene encodes a subunit of brain platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. Nature (London) 1994;370:216–218. doi: 10.1038/370216a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris NR. Nuclear migration. From fungi to the mammalian brain. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1097–101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarricone C, Perrina F, Monzani S, Massimiliano L, Kim MH, Derewenda ZS, Knapp S, Tsai LH, Musacchio A. Coupling PAF signaling to dynein regulation: structure of LIS1 in complex with PAF-acetylhydrolase. Neuron. 2004;44:809–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kardon JR, Vale RD. Regulators of the cytoplasmic dynein motor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:854–65. doi: 10.1038/nrm2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niethammer M, Smith DS, Ayala R, Peng J, Ko J, Lee M, Morabito M, Tsai L. NUDEL Is a Novel Cdk5 Substrate that Associates with LIS1 and Cytoplasmic Dynein. Neuron. 2000;28:697–711. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng Y, Olson EC, Stukenberg PT, Flanagan LA, Kirschner MW, Walsh CA. LIS1 Regulates CNS Lamination by Interacting with mNudE, a Central Component of the Centrosome. Neuron. 2000;28:665–679. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan X, Li F, Liang Y, Shen Y, Zhao X, Huang Q, Zhu X. Human Nudel and NudE as regulators of cytoplasmic dynein in poleward protein transport along the mitotic spindle. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1239–50. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1239-1250.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derewenda U, Tarricone C, Choi WC, Cooper DR, Lukasik S, Perrina F, Tripathy A, Kim MH, Cafiso DS, Musacchio A, Derewenda ZS. The structure of the coiled-coil domain of Ndel1 and the basis of its interaction with Lis1, the causal protein of Miller-Dieker lissencephaly. Structure. 2007;15:1467–81. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKenney RJ, Vershinin M, Kunwar A, Vallee RB, Gross SP. LIS1 and NudE induce a persistent dynein force-producing state. Cell. 2010;141:304–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiu YH, Xiang X, Dawe AL, Morris NR. Deletion of nudC, a nuclear migration gene of Aspergillus nidulans, causes morphological and cell wall abnormalities and is lethal. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1735–49. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.9.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmstaedt K, Laubinger K, Vosskuhl K, Bayram O, Busch S, Hoppert M, Valerius O, Seiler S, Braus GH. The nuclear migration protein NUDF/LIS1 forms a complex with NUDC and BNFA at spindle pole bodies. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1041–52. doi: 10.1128/EC.00071-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawe AL, Caldwell KA, Harris PM, Morris NR, Caldwell GA. Evolutionarily conserved nuclear migration genes required for early embryonic development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Genes Evol. 2001;211:434–41. doi: 10.1007/s004270100176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunniff J, Chiu YH, Morris NR, Warrior R. Characterization of DnudC, the Drosophila homolog of an Aspergillus gene that functions in nuclear motility. Mech Dev. 1997;66:55–68. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreau N, Aumais JP, Prudhomme C, Morris SM, Yu-Lee LY. NUDC expression during amphibian development. Int J Dev Biol. 2001;45:839–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller BA, Zhang MY, Gocke CD, De Souza C, Osmani AH, Lynch C, Davies J, Bell L, Osmani SA. A homolog of the fungal nuclear migration gene nudC is involved in normal and malignant human hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:742–50. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(98)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumoto N, Ledbetter DH. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human NUDC gene. Hum Genet. 1999;104:498–504. doi: 10.1007/s004390050994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou T, Zimmerman W, Liu X, Erikson RL. A mammalian NudC-like protein essential for dynein stability and cell viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9039–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602916103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, Yan X, Cai Y, Lu Y, Si J, Zhou T. NudC-like protein 2 regulates the LIS1/dynein pathway by stabilizing LIS1 with Hsp90. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3499–504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914307107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Ranea JA, Mirey G, Camonis J, Valencia A. p23 and HSP20/alpha-crystallin proteins define a conserved sequence domain present in other eukaryotic protein families. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:162–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Li M, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Jin S, Xie G, Liu Z, Wang S, Zhang H, Shen L, Ge H. RNA interference targeting CML66, a novel tumor antigen, inhibits proliferation, invasion and metastasis of HeLa cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:127–38. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang XF, Wu CJ, McLaughlin S, Chillemi A, Wang KS, Canning C, Alyea EP, Kantoff P, Soiffer RJ, Dranoff G, Ritz J. CML66, a broadly immunogenic tumor antigen, elicits a humoral immune response associated with remission of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7492–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131590998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gocke CD, Osmani SA, Miller BA. The human homologue of the Aspergillus nuclear migration gene nudC is preferentially expressed in dividing cells and ciliated epithelia. Histochem Cell Biol. 2000;114:293–301. doi: 10.1007/s004180000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang MY, Huang NN, Clawson GA, Osmani SA, Pan W, Xin P, Razzaque MS, Miller BA. Involvement of the fungal nuclear migration gene nudC human homolog in cell proliferation and mitotic spindle formation. Exp Cell Res. 2002;273:73–84. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou T, Aumais JP, Liu X, Yu-Lee LY, Erikson RL. A role for Plk1 phosphorylation of NudC in cytokinesis. Dev Cell. 2003;5:127–38. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aumais JP, Williams SN, Luo W, Nishino M, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Lin SH, Yu-Lee LY. Role for NudC, a dynein-associated nuclear movement protein, in mitosis and cytokinesis. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1991–2003. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishino M, Kurasawa Y, Evans R, Lin SH, Brinkley BR, Yu-Lee LY. NudC is required for Plk1 targeting to the kinetochore and chromosome congression. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1414–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hatakeyama H, Kondo T, Fujii K, Nakanishi Y, Kato H, Fukuda S, Hirohashi S. Protein clusters associated with carcinogenesis, histological differentiation and nodal metastasis in esophageal cancer. Proteomics. 2006;6:6300–16. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin SH, Nishino M, Luo W, Aumais JP, Galfione M, Kuang J, Yu-Lee LY. Inhibition of prostate tumor growth by overexpression of NudC, a microtubule motor-associated protein. Oncogene. 2004;23:2499–506. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartmann TB, Mattern E, Wiedemann N, van Doorn R, Willemze R, Niikura T, Hildenbrand R, Schadendorf D, Eichmuller SB. Identification of selectively expressed genes and antigens in CTCL. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:324–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki SO, McKenney RJ, Mawatari S, Mizuguchi M, Mikami A, Iwaki T, Goldman JE, Canoll P, Vallee RB. Expression patterns of LIS1, dynein and their interaction partners dynactin, NudE, NudEL and NudC in human gliomas suggest roles in invasion and proliferation. Acta Neuropathologica. 2007;113:591–599. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris SM, Albrecht U, Reiner O, Eichele G, Yu-Lee LY. The lissencephaly gene product Lis1, a protein involved in neuronal migration, interacts with a nuclear movement protein, NudC. Curr Biol. 1998;8:603–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu XJ, Liu X, Jin Q, Cai Y, Yang Y, Zhou T. The L279P mutation of nuclear distribution gene C (NudC) influences its chaperone activity and lissencephaly protein 1 (LIS1) stability. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29903–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aumais JP, Tunstead JR, McNeil RS, Schaar BT, McConnell SK, Lin SH, Clark GD, Yu-Lee LY. NudC associates with Lis1 and the dynein motor at the leading pole of neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riera J, Rodriguez R, Carcedo MT, Campa VM, Ramos S, Lazo PS. Isolation and characterization of nudC from mouse macrophages, a gene implicated in the inflammatory response through the regulation of PAF-AH(I) activity. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3057–62. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamada M, Toba S, Takitoh T, Yoshida Y, Mori D, Nakamura T, Iwane AH, Yanagida T, Imai H, Yu-Lee LY, Schroer T, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hirotsune S. mNUDC is required for plus-end-directed transport of cytoplasmic dynein and dynactins by kinesin-1. Embo J. 2010;29:517–31. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faircloth LM, Churchill PF, Caldwell GA, Caldwell KA. The microtubule-associated protein, NUD-1, exhibits chaperone activity in vitro. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14:95–103. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0061-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen WM, Yu B, Zhang Q, Xu P. Identification of the residues in the extracellular domain of thrombopoietin receptor involved in the binding of thrombopoietin and a nuclear distribution protein (human NUDC) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26697–709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.120956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pang SF, Li XK, Zhang Q, Yang F, Xu P. Interference RNA (RNAi)-based silencing of endogenous thrombopoietin receptor (Mpl) in Dami cells resulted in decreased hNUDC-mediated megakaryocyte proliferation and differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:3563–73. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang YS, Zhang YP, Xu P. hNUDC promotes the cell proliferation and differentiation in a leukemic cell line via activation of the thrombopoietin receptor (Mpl) Leukemia. 2008;22:1018–25. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang YP, Tang YS, Chen XS, Xu P. Regulation of cell differentiation by hNUDC via a Mpl-dependent mechanism in NIH 3T3 cells. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3210–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei MX, Yang Y, Ge YC, Xu P. Functional characterization of hNUDC as a novel accumulator that specifically acts on in vitro megakaryocytopoiesis and in vivo platelet production. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:429–39. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan RM, Yang Y, Wei MX, Yu XB, Ge YC, Xu P. A microtubule associated protein (hNUDC) binds to the extracellular domain of thrombopoietin receptor (Mpl) J Cell Biochem. 2005;96:741–50. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riera J, Lazo PS. The mammalian NudC-like genes: a family with functions other than regulating nuclear distribution. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:2383–90. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0025-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–4. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srivastava M, Begovic E, Chapman J, Putnam NH, Hellsten U, Kawashima T, Kuo A, Mitros T, Salamov A, Carpenter ML, Signorovitch AY, Moreno MA, Kamm K, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Shapiro H, Grigoriev IV, Buss LW, Schierwater B, Dellaporta SL, Rokhsar DS. The Trichoplax genome and the nature of placozoans. Nature. 2008;454:955–60. doi: 10.1038/nature07191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kajan L, Rychlewski L. Evaluation of 3D-Jury on CASP7 models. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:304. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ginalski K, Elofsson A, Fischer D, Rychlewski L. 3D-Jury: a simple approach to improve protein structure predictions. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1015–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cooper DR, Boczek T, Grelewska K, Pinkowska M, Sikorska M, Zawadzki M, Derewenda Z. Protein crystallization by surface entropy reduction: optimization of the SER strategy. Acta Cryst D. 2007;63:636–45. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907010931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldschmidt L, Cooper DR, Derewenda ZS, Eisenberg D. Toward rational protein crystallization: A Web server for the design of crystallizable protein variants. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1569–76. doi: 10.1110/ps.072914007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Derewenda ZS, Vekilov PG. Entropy and surface engineering in protein crystallization. Acta Cryst D. 2006;62:116–24. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905035237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Derewenda ZS. Rational protein crystallization by mutational surface engineering. Structure. 2004;12:529–35. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weaver AJ, Sullivan WP, Felts SJ, Owen BA, Toft DO. Crystal structure and activity of human p23, a heat shock protein 90 co-chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23045–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bagneris C, Bateman OA, Naylor CE, Cronin N, Boelens WC, Keep NH, Slingsby C. Crystal structures of alpha-crystallin domain dimers of alphaB-crystallin and Hsp20. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:1242–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holm L, Kaariainen S, Rosenstrom P, Schenkel A. Searching protein structure databases with DaliLite v.3. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2780–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holm L, Kaariainen S, Wilton C, Plewczynski D. Using Dali for structural comparison of proteins. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2006;Chapter 5(Unit 5):5. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0505s14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang M, Kadota Y, Prodromou C, Shirasu K, Pearl LH. Structural basis for assembly of Hsp90-Sgt1-CHORD protein complexes: implications for chaperoning of NLR innate immunity receptors. Mol Cell. 2010;39:269–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kadota Y, Shirasu K, Guerois R. NLR sensors meet at the SGT1-HSP90 crossroad. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ali MM, Roe SM, Vaughan CK, Meyer P, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Prodromou C, Pearl LH. Crystal structure of an Hsp90-nucleotide-p23/Sba1 closed chaperone complex. Nature. 2006;440:1013–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh M, Gonzales FA, Cascio D, Heckmann N, Chanfreau G, Feigon J. Structure and functional studies of the CS domain of the essential H/ACA ribonucleoparticle assembly protein SHQ1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1906–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807337200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, Hotz HR, Ceric G, Forslund K, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer EL, Bateman A. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D281–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bateman A, Birney E, Cerruti L, Durbin R, Etwiller L, Eddy SR, Griffiths-Jones S, Howe KL, Marshall M, Sonnhammer EL. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:276–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhattacharya S, Lee YT, Michowski W, Jastrzebska B, Filipek A, Kuznicki J, Chazin WJ. The modular structure of SIP facilitates its role in stabilizing multiprotein assemblies. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9462–71. doi: 10.1021/bi0502689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Santelli E, Leone M, Li C, Fukushima T, Preece NE, Olson AJ, Ely KR, Reed JC, Pellecchia M, Liddington RC, Matsuzawa S. Structural analysis of Siah1-Siah-interacting protein interactions and insights into the assembly of an E3 ligase multiprotein complex. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34278–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clark JI, Muchowski PJ. Small heat-shock proteins and their potential role in human disease. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:52–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lupas A. Predicting coiled-coil regions in proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:388–93. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu H, Domingues FS, Sommer I, Lengauer T. NOXclass: prediction of protein-protein interaction types. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perez DE, Hoyer JS, Johnson AI, Moody ZR, Lopez J, Kaplinsky NJ. BOBBER1 is a noncanonical Arabidopsis small heat shock protein required for both development and thermotolerance. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:241–52. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.142125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burdette AJ, Churchill PF, Caldwell GA, Caldwell KA. The early-onset torsion dystonia-associated protein, torsinA, displays molecular chaperone activity in vitro. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010;15:605–17. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0173-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cherepkova OA, Lyutova EM, Eronina TB, Gurvits BY. Chaperone-like activity of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saibil HR. Chaperone machines in action. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McHaourab HS, Godar JA, Stewart PL. Structure and mechanism of protein stability sensors: chaperone activity of small heat shock proteins. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3828–37. doi: 10.1021/bi900212j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]