Abstract

Reduction of traumatic unilateral locked facets of the cervical spine can be accomplished by closed or open means. If closed reduction is unsuccessful, then open reduction is indicated. The previously described techniques of open reduction of a unilateral locked facets of the cervical spine in the literature included drilling facet, forceful manipulation or using special equipment. We describe a reduction technique that uses a basic spinal curette, in a forceless manner, and it does not need facet drilling. We have successfully used this technique in 5 consecutive patients with unilateral locked facets. There have been no complications related to this technique.

Keywords: Cervical spine, Unilateral locked facets, Spinal reduction

Introduction

Locked facets of the spine is a result of a flexion-rotation or flexion-distraction type of injury [1]. This mechanism of injury makes the inferior facet of the rostal vertebra slip forward and over the superior facet of the caudal vertebra, and this can occur unilaterally or bilaterally (Fig. 1). Treatment of this condition requires reduction and stabilization. Reduction can be accomplished by closed or open means. In the case that a closed reduction has proved futile, open reduction is then indicated [2-5]. We present here a simple effective technique for open reduction of locked facets of the cervical spine.

Fig. 1.

Locked facets on computed tomography (CT). The reconstructed CT shows unilateral locked facets of C6-7. Note the inferior facet of the rostal vertebra is situated anterior to the superior facet of the caudal vertebra (arrow).

Technical Note

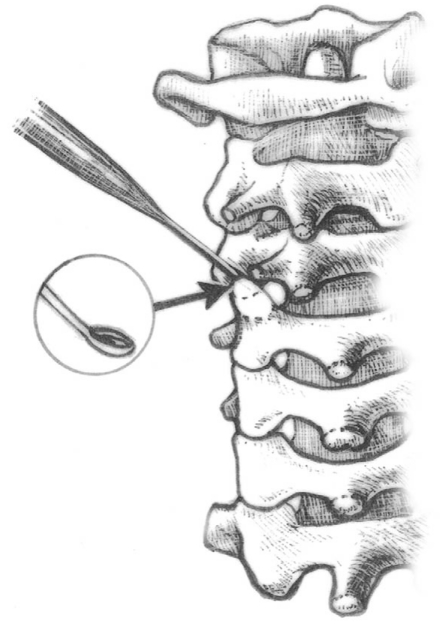

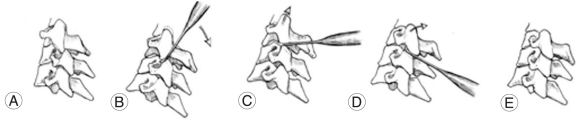

After unsuccessful closed reduction, and there is no anterior compression such as disc herniation, the injured patient is transferred to the operating theater with adequate immobilization. Following awake intubation and anesthetic induction, the patient is placed in the prone position; the head is fixed in a rigid head holder in a case of cervical-level locked facets, and on a horse shoe head support in a case of thoracic-level locked facets. The midline incision is used. The paraspinal muscles are dissected until the full extent of the injured facets is visualized. The level may be verified with fluoroscopy, if needed. After the locked facets are identified, the small straight spinal curette (Fig. 2) is placed between the inferior facet of the rostal vertebra and the superior facet of the caudal vertebra. With gentle pressure and a twisting maneuver, the curette tip will slide between them. The curette is then turned so that the cup side docks with the inferior edge of the rostal facet. Care must be taken not to place the tip of the curette more deeply than the inferior edge of the rostal facet to avoid injuring the exiting nerve root, which is located near the inferior edge of the rostal facet. The handle of the curette is then gently pulled caudally so that the rostal facet is levered up and over the caudal facet (Figs. 3 and 4). A surgeon then inspects whether or not the reduction is completed. If not, this maneuver can be repeated. In case that the dislocated facets are so impacted that the curette could not reach the inferior edge of the rostal facet, the posterior surface of the rostal facet can be used as an initial docking point for levering. After the facets are less impacted, the curette can then be placed and docked at the inferior edge of the facet, as described earlier. A fusion procedure can be performed after the reduction is completed.

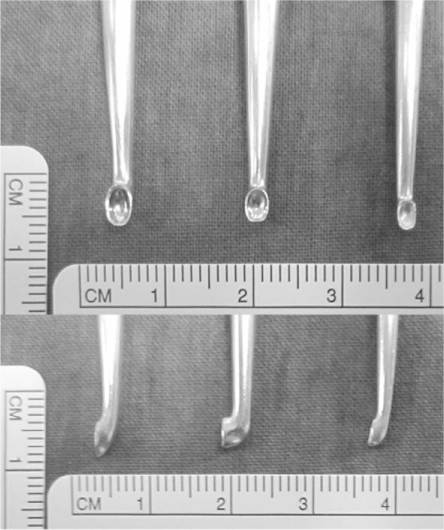

Fig. 2.

Spinal curettes. Size and shape of the tips of the straight spinal curettes used for reduction in the front and side views.

Fig. 3.

Locked facet reduction. Reducing the locked facets by a spinal curette.

Fig. 4.

Locked facet reduction maneuver. (A) Note the locked facets. (B) The curette is placed between the locked facets and the curette is turned so that the cup side docks with the inferior edge of the facet. (C, D) The curette is gently pull caudally so that the inferior facet is levered up and over the superior facet. (E) The reduction is completed.

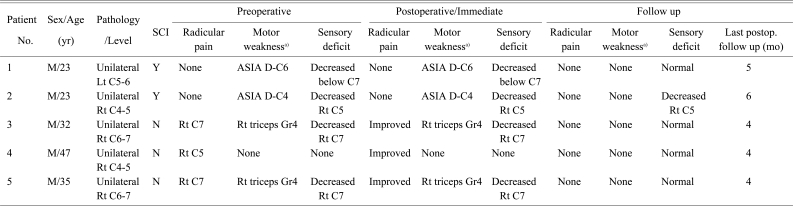

We have changed the practice from drilling facets or manual distraction of the spinous processes to this presented technique. This technique has been successfully used to treat 5 consecutive patients with unilateral cervical locked facets (Table 1). Following reduction, the spines were stabilized by spinous process wiring and fusion. There was no neurological worsening or vascular complication in these 5 patients. All the patients showed good spinal alignment and stability as determined by dynamic radiographic studies after 3-month follow up.

Table 1.

Data and preoperative and postoperative neurological status

SCI: Spinal cord injury, Postop.: Postoperative, M: Male, Lt: Left, Y/N: Presence or absence of spinal cord injury as determined by neurological status and magnetic resonance imaging, Rt: Right.

a)ASIA: American Spinal Injury Association impairment scale.

Discussion

The majority of locked facets occur at the cervical level, but they can also be found at the thoracic and lumbar spine [1,6,7]. The success rate of closed reduction is higher for bilateral locked facets as compare to the unilateral ones [2-4]. When closed reduction fails, open reduction is then indicated. When there is no anterior compression, posterior open reduction is the approach of choice [2-5,8]. The techniques described in the literature include partial superior facetectomy, using a specially made lamina spreader and spinous process traction [4,5,8,9].

We describe an alternative technique of reduction using a spinal curette. This technique has a number of advantages. First, using a long lever arm of a spinal curette allows a surgeon to use gentle force in a controlled manner to accomplish reduction. This is especially true in the unilateral locked facets where some stability remains and these unilateral locked facets usually require forceful distraction of the spinous processes for reduction. Second, this technique obviates the need to remove the superior facet of the caudal vertebra and so parts of the biomechanical properties of the facets are preserved. Third, it can be performed even if the spinous process or lamina is damaged or if they are not available. However, precautionary measures must be adhered to avoid injury to the surrounding neurovascular structures. First, the curette must not be placed too deeply beyond the tip of the inferior facet of the rostal vertebra as this may injure the anteriorly placed exiting root or vertebral artery. Second, while attempting to place the tip of the curette in between the facets, a surgeon should avoid using excessive force because slippage or plunging anterior or medially may occur and this can lead to serious damage of the exiting root, the vertebral artery or the spinal cord. Instead, a surgeon may use gentle force and twisting of the curette to help glide the tip of the curette into between the facets. Third, the size of the curette tip should be small so that it does not cause excessive anterior displacement of the inferior facet, which may in turn compress on the exiting nerve root.

As compared to Fazl's technique, the strengths of this technique are: 1) it can be performed even if the lamina is fractured or not available, 2) a spinal curette is more readily available in a basic spinal instrument set than the "modified" interlamina spreader used in Fazl's technique, and 3) the risk of inadvertent slippage of the instrument into a spinal canal is intuitively less than Fazl's technique. The weakness of this technique is the exiting root and vertebral artery at the dislocated level may be at the greater risk of injury if the curette is placed too deeply during the reduction maneuver.

The contraindication for this technique is a presence of disk herniation, which should be decompressed anteriorly [9,10]. The presence of facet fracture or bone fragments in a neuroforamina is also a contraindication as the risk of nerve root injury will increase from this technique.

This technique is an effective alternative method of reducing unilateral locked facets of the cervical spine.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Soonthorn Tansiri for illustrations in this article.

References

- 1.Crawford NR, Duggal N, Chamberlain RH, Park SC, Sonntag VK, Dickman CA. Unilateral cervical facet dislocation: injury mechanism and biomechanical consequences. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:1858–1864. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200209010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf A, Levi L, Mirvis S, et al. Operative management of bilateral facet dislocation. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:883–890. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.6.0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu ZS, Yue JJ, Wei F, Liu ZJ, Chen ZQ, Dang GT. Treatment of cervical dislocation with locked facets. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120:216–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braakman R, Vinken PJ. Unilateral facet interlocking in the lower cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1967;49:249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro SA. Management of unilateral locked facet of the cervical spine. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:832–837. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy SJ, Al-Holou WN, Leveque JC, La Marca F, Park P. Traumatic lateral spondylolisthesis of the lumbar spine with a unilateral locked facet: description of an unusual injury, probable mechanism, and management. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:576–580. doi: 10.3171/SPI.2008.6.08301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori K, Hukuda S, Katsuura A, Saruhashi Y, Asajima S. Traumatic bilateral locked facet at L4-5: report of a case associated with incorrect use of a three-point seatbelt. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:602–605. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fazl M, Pirouzmand F. Intraoperative reduction of locked facets in the cervical spine by use of a modified interlaminar spreader: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:444–445. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200102000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim MR, Mathur S, Vaccaro AR. Open reduction of unilateral and bilateral facet dislocations. In: Vaccaro AR, Albert TJ, editors. Spine surgery: tricks of the trade. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme; 2009. pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ordonez BJ, Benzel EC, Naderi S, Weller SJ. Cervical facet dislocation: techniques for ventral reduction and stabilization. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(1 Suppl):18–23. doi: 10.3171/spi.2000.92.1.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]