Abstract

Blockers of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) ameliorate cognitive deficits and some aspects of brain injury after whole-brain irradiation. We investigated whether treatment with the angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist L-158,809 at a dose that protects cognitive function after fractionated whole-brain irradiation reduced radiation-induced neuroinflammation and changes in hippocampal neurogenesis, well-characterized effects that are associated with radiation-induced brain injury. Male F344 rats received L-158,809 before, during and after a single 10-Gy dose of radiation. Expression of cytokines, angiotensin II receptors and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 was evaluated by real-time PCR 24 h, 1 week and 12 weeks after irradiation. At the latter times, microglial density and proliferating and activated microglia were analyzed in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Cell proliferation and neurogenesis were also quantified in the dentate subgranular zone. L-158,809 treatment modestly increased mRNA expression for Ang II receptors and TNF-α but had no effect on radiation-induced effects on hippocampal microglia or neurogenesis. Thus, although L-158,809 ameliorates cognitive deficits after whole-brain irradiation, the drug did not mitigate the neuroinflammatory microglial response or rescue neurogenesis. Additional studies are required to elucidate other mechanisms of normal tissue injury that may be modulated by RAAS blockers.

INTRODUCTION

Each year over 220,000 patients in the United States are diagnosed with central nervous system (CNS) cancers or brain metastases (1, 2). Many of those patients are successfully treated with large-field or whole-brain irradiation (3), but approximately 50% of survivors present months to years later with radiotherapy-associated progressive cognitive deficits that decrease their quality of life (4–6). The cellular and molecular mechanisms of chronic radiation-induced brain injury are not fully understood, but acute and chronic neuroinflammatory changes follow whole-brain irradiation and may contribute (7). Activated microglia can alter neural function by changing their production of cytokines and/or trophic factors, modulating synaptic plasticity, altering the neuronal microenvironment, and reducing ongoing neurogenesis (8–10). Inflammatory effects on neurogenesis have been linked to cognitive dysfunction (11–13), suggesting that interventions that modulate inflammation and/or protect neurogenesis may ameliorate radiation-induced neural injury. Cellular markers of the neurobiological response to radiation (7, 8, 14–16) facilitate assessment of the efficacy and possible mechanisms of action of therapeutic agents.

Blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is an attractive therapeutic target for reducing radiation-induced inflammation and brain injury. Several organs, including the brain, have an intrinsic RAAS that functions independently from the systemic RAAS (17). Angiotensin II (Ang II), the best-characterized biologically active RAAS peptide, contributes to inflammatory responses and influences neuronal function in the brain via angiotensin II type 1 (AT1R) and type 2 (AT2R) receptors (18). Previous studies demonstrated (by immunolabeling and/or receptor binding) expression of Ang II receptors on neurons and glia within the hippocampus and in other regions of the CNS (19–22). RAAS inhibition with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) and/or an AT1R antagonist (AT1RA) ameliorates radiation-induced damage in the lung, kidney and optic nerve (23–25), changes in neurogenesis (26), and cognitive dysfunction (27–29). It is easier to interpret effects of AT1R blockade than ACE inhibition, since ACE cleaves biologically active peptides that are unrelated to the RAAS (30), so we have focused on evaluating the effects of RAAS blockade with an AT1RA. L-158,809 is 10–100 times more potent in vivo than the widely used AT1RA losartan (31), attenuates radiation-induced damage in the kidney and lung (23, 24), and, like other drugs in its class, is lipophilic and crosses the blood-brain barrier (BBB, see Discussion) (32). Moreover, the drug ameliorates radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction when administered during and after fractionated whole-brain irradiation (27, 28).

We found previously that L-158,809 treatment did not alter neurogenesis or microglial markers of neuroinflammation at 6 and 12 months after fractionated irradiation (16), at which time behavioral testing demonstrated radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction that was ameliorated by L-158,809 (27). Given that L-158,809 treatment for only a few weeks after irradiation also protects rats from cognitive deficits (27), we hypothesized that benefits of the drug for cognitive function might involve reducing inflammatory processes in the period immediately after irradiation. Therefore, in this study, we assessed whether treatment with L-158,809 during and for up to 12 weeks after irradiation ameliorated radiation-induced neuroinflammation and changes in neurogenesis. We tested a single whole-brain dose of radiation in this analysis of shorter-term effects, since (1) most data concerning radiation-induced neurobiological changes in rodents are from single-dose studies (7, 14, 15 33–35), (2) a single 10-Gy dose can cause cognitive dysfunction in rodents (35–41), and (3) it is more straightforward to interpret acute and short-term neurobiological changes after a single dose than after multiple doses over an extended period. Previous studies from this and other laboratories demonstrated that 10 Gy radiation produces a microglial inflammatory response and decreases neurogenesis in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus (DG) of young adult rats (14, 37, 41–43), robust neurobiological responses against which to test the efficacy of drug treatment.

We evaluated expression of Ang II receptors and ACE2 to test for effects of the AT1RA and whole-brain irradiation on the local brain RAAS. Since activation of the AT1R produces pro-inflammatory actions (44, 45), we tested whether whole-brain irradiation and L-158,809 affected expression levels of cytokines that have been implicated in studies of radiation-induced neuroinflammation (46–48). At the cellular level, we assessed the number of microglia and the percentages of proliferating or activated microglia in the DG granule cell layer (GCL)/hilus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Methods are summarized below, and details are provided as Supplementary Information (http://dx.doi.org/10.1667/RR2560.1.S1).

Animals

Sixty male Fischer 344 rats were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). Rats were housed individually on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water and were acclimated for 3 weeks prior to irradiation at 12 weeks of age. The animal facility at Wake Forest University School of Medicine is accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and complies with Public Health Service-National Institutes of Health and institutional policies and standards for laboratory animal care. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drug and Radiation Treatment

L-158,809 treatment (20 mg/liter drinking water; average dose 2 mg/kg/day; see the Results) began 5 days before whole-brain irradiation and continued throughout the course of the study (27). Animals were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: (1) sham irradiation, (2) whole-brain irradiation, (3) sham irradiation/L-158,809 and (4) whole-brain irradiation/L-158,809. At 12 weeks of age rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and irradiated (10 Gy) in a 137Cs irradiator with collimating devices for delivery to the whole brain and lead shielding to protect the eyes and body. Sham-irradiated rats were anesthetized but not irradiated. Neurobiological changes were assessed at 24 h, 1 week and 12 weeks postirradiation. The 24-h time provided a baseline for changes in the weeks after irradiation, since previous studies demonstrated that after single-dose irradiation levels of inflammatory cytokines were at or near control levels at 24 h after a more acute increase (peaking at 4 h) (49), and since acute, radiation-induced cell death in the DG is completed by 24 h (43). The other times were based on previous evidence from young rodents for an early radiation-induced decrease in proliferation within the SGZ (24 h) followed by a transient increase (1 week) in proliferation and then a sustained decrease in proliferation and neurogenesis (12 weeks) (43). In addition, increased microglial activation in the DG GCL/hilus has been reported at 12 weeks after whole-brain irradiation (8, 34).

Tissue Processing

Rats from each group were deeply anesthetized and decapitated at the end of the designated survival period (n = 4–8/group). Brains were rapidly extracted, chilled and hemisected at the midline. The right hippocampus was removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until processing for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The left hemisphere was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde; serial coronal sections through the entire hippocampal formation (bregma −1.8 to −6.9) (50) were cut and stored at −20°C until processed for immunohistochemical or immunofluorescence labeling.

Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Gene expression analyses for interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), as well as for Ang II receptors and ACE2, were completed by qRT-PCR using fluorogenic 5′nuclease assay technology with TaqMan® probes and primers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). RNA was isolated from whole hippocampus and reverse transcribed. Amplification of individual genes was performed as described in detail in the Supplementary Information. Relative quantification was calculated by the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method as described (51).

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Primary antibodies used for immunohistochemical analysis of cell proliferation and microglia recognized the Ki67 antigen (proliferating cells) (52), ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule-1 (Iba1, macrophages and microglia) (53), and CD68 (clone ED1, upregulated in phagocytic macrophages and microglia) (54). Iba1+ and ED1+ cells are referred to here as microglia since little, if any, infiltration of peripheral macrophages likely occurred under the conditions of this study (see the Discussion). Primary antibodies were detected with biotinylated secondary antibodies and the avidin-biotin complex/diaminobenzidine method; Ki67 and Iba1 were labeled sequentially in the same series of sections using Vector SG and diaminobenzidine, respectively. For immunofluorescence labeling of neuroblasts/immature neurons in the dorso-medial DG, binding of anti-doublecortin (DCX) (55, 56) was visualized with a cyanine-5-conjugated secondary antibody.

Quantitative Analysis

Stereological estimates of the densities of microglia (Iba1+ cells), proliferating microglia (Ki67+/Iba1+), and activated microglia (ED1+) in the DG GCL/hilus were generated using the optical disector (57). Labeled cells that were present at high density (Iba1+ cells in all groups, Ki67+/Iba1+ and ED1+ cells in irradiated rats at 1 week) were counted using the optical fractionator workflow on the Stereo Investigator system (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT). The low density and non-uniform distribution of Ki67+/Iba1+ cells and ED1+ cells in the remaining groups required exhaustive counting within the entire DG GCL/hilus and was performed using the Neurolucida system (MBF Bioscience). Cell counts in the DG GCL/hilus were expressed as the density of positive cells per mm3, and the percentages of proliferating and activated microglia were calculated from their estimated densities compared to the total density of microglia. In addition to counts in the DG GCL/hilus, Ki67+/Iba1− cells and Ki67+/Iba1+ cells were counted exhaustively in the DG SGZ (14) and expressed as linear densities (cells per millimeter of SGZ). DCX+ cells were counted using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope and a 63× oil-immersion objective moving field by field along the extent of the SGZ (complete z-series through the depth of the section in approximately 25 fields per section). The length of the SGZ in each section analyzed was measured using Neurolucida, and the densities of DCX+ cells were expressed as number per millimeter of SGZ.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Sigmastat 3.0 (SYSTAT Software, San Jose, CA). With one exception (ED1+ cells at 1 week), the main effects of irradiation status (sham compared to whole brain) and drug status (water compared to L-158,809) and interactions of the main effects were evaluated using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a significance threshold of P ≤ 0.05. Where significant main effects were indicated, Holm-Sidek post hoc tests were completed. At 1 week, ED1+ cells were too rare in sham-irradiated animals for reliable quantification, so sham-irradiated animals were excluded from analysis and irradiated rats with and without drug treatment were compared by t tests. Large radiation effects on many variables resulted in non-normal distributions and/or unequal variance, violations of the assumptions of ANOVA that increased the possibility of Type I errors. The significant differences indicated in the affected cases were robust, however, and were confirmed using a non-parametric ANOVA on ranks (indicated where applicable).

RESULTS

Effects of Whole-Brain Irradiation and AT1R Antagonism on Body Weight and Water Consumption

In the 1-week survival group, whole-brain irradiation had no effect on body weight or water consumption. L-158,809 treatment increased water consumption approximately 25% [F(1,20) = 26.69, P < 0.001] but did not alter body weight. In the 12-week survival group (Supplementary Fig. 1A and B; http://dx.doi.org/10.1667/RR2560.1.S2), whole-brain irradiation slightly decreased body weight [F(1,12) = 10.50, P = 0.001] but had no effect on water consumption, whereas L-158,809 treatment decreased weight and increased drinking [body weight F(1,12) = 324.62, P < 0.001; water consumption F(1,12) = 279.08, P < 0.001]. Based on weight and water consumption, the average daily dose in L-158,809 treated rats remained at approximately 2 mg/kg/day throughout the course of the experiment and did not differ between irradiated and sham-irradiated rats (Supplementary Fig. 1C; http://dx.doi.org/10.1667/RR2560.1.S2).

Effects of Whole-Brain Irradiation and AT1R Antagonism on Cytokines and Elements of the Brain RAS

Cytokine expression

The results of quantitative RT-PCR analysis of cytokine gene expression are summarized in Table 1. At 24 h after treatment, TNF-α expression was reduced 25–30% in irradiated rats [F(1,16) = 14.66, P = 0.001], with no effect of drug treatment. At 1 week postirradiation, there were no significant differences in TNF-α mRNA levels among the experimental groups. At 12 weeks, neither WBI nor L-158,809 resulted in an overall change in TNF-α expression, but there was a significant interaction between the factors [F(1,14) = 5.74, P = 0.03]. Specifically, TNF-α expression increased in irradiated rats that did not receive L-158,809 but not in drug-treated rats, and among sham-irradiated animals a small but significant increase in TNF-α expression was evident in drug-treated rats. IL-6 expression was decreased approximately 60% by radiation at 1 week postirradiation regardless of drug treatment [main effect whole-brain irradiation F(1,14) = 20.87, P < 0.001] but was not affected by radiation or drug treatment at 24 h or 12 weeks. Expression of IL-1β and TGF-β was not affected by radiation or drug treatment at any time.

TABLE 1.

Gene Expression after Whole-Brain Irradiation and AT1R Antagonism

| Treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Gene | Sham irradiation | Sham irradiation/ L-158,809 |

Whole-brain irradiation | Whole-brain irradiation/ L-158,809 |

| 24 h | TNF-α | 1.00 (0.8–1.26) | 1.06 (0.85–1.32) | 0.67 (0.53–0.85)* | 0.73 (0.54–0.98)** |

| IL-6 | 1.00 (0.82–1.21) | 1.23 (0.95–1.59) | 1.35 (1.04–1.75) | 1.27 (1.06–1.52) | |

| AT1aR | 1.00 (0.77–1.3) | 1.04 (0.55–1.27) | 0.83 (0.7–1.02) | 1.00 (0.8–1.29) | |

| AT2R | 1.00 (0.59–1.71) | 1.28 (0.99–1.64) | 1.00 (0.73–1.37) | 1.15 (0.83–1.61) | |

| 1 week | TNF-α | 1.00 (0.88–1.13) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 1.27 (0.91–1.75) | 1.20 (1.05–1.39) |

| IL-6 | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | 1.08 (0.98–1.17) | 0.63 (0.44–0.9)* | 0.62 (0.47–0.8)** | |

| AT1aR | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | 1.38 (1.14–1.68)* | 1.05 (0.81–1.37) | 1.13 (0.81–1.58) | |

| AT2R | 1.00 (0.75–1.33) | 1.23 (0.96–1.58) | 0.87 (0.66–1.14) | 1.26 (0.99–1.59)† | |

| 12 weeks | TNF-ᆆ | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | 1.27 (0.97–1.65)* | 1.41 (1.11–1.71)* | 1.25 (1.21–1.31) |

| IL-6 | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) | 1.11 (0.66–1.91) | 0.84 (0.72–0.98) | 0.85 (0.54–1.34) | |

| AT1aR | 1.00 (0.83–1.21) | 1.14 (0.82–1.32) | 1.00 (0.76–1.32) | 1.01 (0.86–1.18) | |

| AT2R | 1.00 (0.57–1.75) | 0.93 (0.71–1.02) | 0.69 (0.56–0.86) | 1.22 (0.73–2.04) | |

Notes. Values represent mean relative induction (range) normalized to values for GAPDH, endogenous control, and relative to sham irradiation. Values significantly different (by Holm-Sidek post hoc tests)

from sham irradiation (P < 0.05),

from sham irradiation/L-158,809 (P < 0.05), or

from whole-brain irradiation (P < 0.05),

interaction (P = 0.03). Values are not shown for IL-1β, TGF-β1 or ACE2, which did not change significantly under any condition.

Ang II receptors and ACE2

Levels of mRNA for the AT1R and the AT2R were minimally affected by radiation and L-158,809 (Table 1). At 1 week postirradiation, but not at 24 h or 12 weeks, small drug-induced increases in AT1R and AT2R expression were apparent in sham-irradiated and irradiated animals, respectively [AT1R main effect drug treatment F(1,16) = 4.63, P = 0.047; AT2R main effect drug treatment F(1,15) = 6.36, P = 0.02]. Western blot analysis in a separate (comparably treated) group of rats, however, did not reveal changes in AT1R at the protein level (data not shown; antibodies suitable for Western blot analysis of the AT2R were not available). ACE2 mRNA expression was not affected by radiation or drug treatment at any time.

Effects of Whole-Brain Irradiation and AT1R Antagonism on Microglia in the DG GCL/Hilus

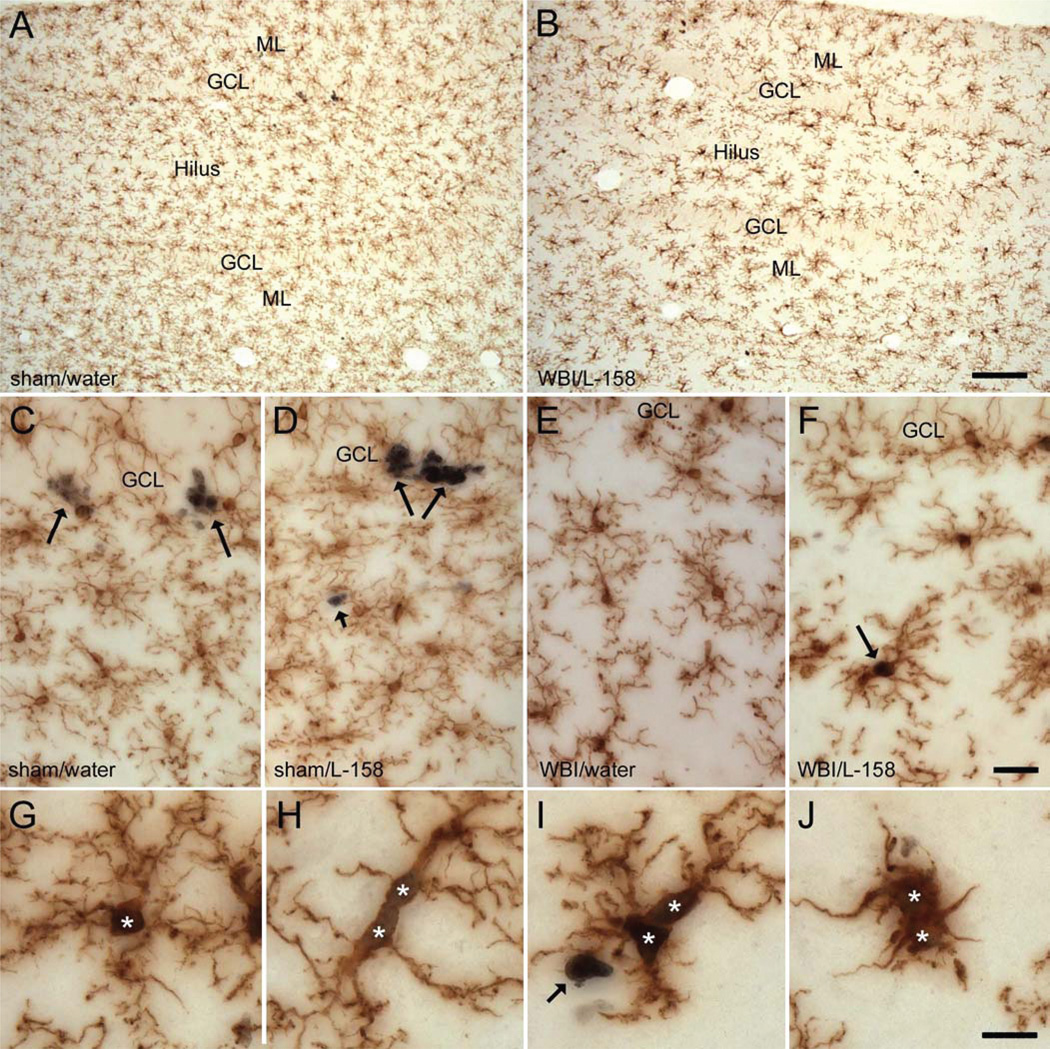

In sham-irradiated rats, Iba1-labeled cells bore the highly ramified processes indicative of “resting” microglia (Fig. 1) (58), and drug treatment had no apparent effect on the cells’ morphology. In irradiated rats, at 1 and 12 weeks after irradiation, many microglia exhibited a moderately activated phenotype; i.e., microglial processes appeared somewhat shorter and wider than in sham-irradiated animals, and the intensity of Iba1 labeling appeared increased. Iba1+ cells with the appearance of activated, macrophage-like cells (large, round cell bodies and only a few short processes, Fig. 2J) (58) were seen rarely and only in irradiated rats. Overall, there was a broad range of microglial morphologies in irradiated animals, and many cells appeared comparable to those in sham-irradiated rats. Drug treatment had no apparent effect on the morphology of microglia in irradiated rats.

FIG. 1.

Double immunohistochemical labeling of microglia and proliferating cells. The distribution of Iba1+ microglia (brown) was more or less homogeneous in both sham-irradiated (panel A) and irradiated (panel B) rats, although subtle differences in the density of microglia and processes made it possible to distinguish the GCL from the hilus and the molecular layer (ML) of the DG. Whole-brain irradiation (WBI) resulted in regression of some finer microglial processes and a moderate increase in the intensity of Iba1 labeling (compare panels B and A and panels E, F and C, D). Ki67 labeling of proliferating cells was readily resolved at higher magnification in sham-irradiated (panels C, D) and irradiated panels (panels E–J) rats. In sham-irradiated rats (panels C, D), many Ki67+/Iba1− cells (long arrows, presumptive neuronal progenitor cells) were present in the SGZ at the border of the GCL and hilus. Ki67+/Iba1− cells in other regions (short arrow in panels D and I; presumptive macroglial progenitors) typically occurred singly or in pairs. In irradiated rats (panels E, F), fewer Ki67+/Iba1− cells were evident in the SGZ while Ki67+/Iba1+ proliferating microglia were more abundant throughout the DG (arrow in panel F and cells at higher magnification in panels G–J). Ki67+/Iba1+ proliferating microglia in irradiated rats exhibited a variety of morphologies (panels G–J; asterisks indicate Ki67+ nuclei), similar to the microglial population as a whole. Drug treatment had no apparent effect on Iba1 labeling. Scale bars = 125 µm (panels A, B), 25 µm (panels C–F), 12.5 µm (panels G–J).

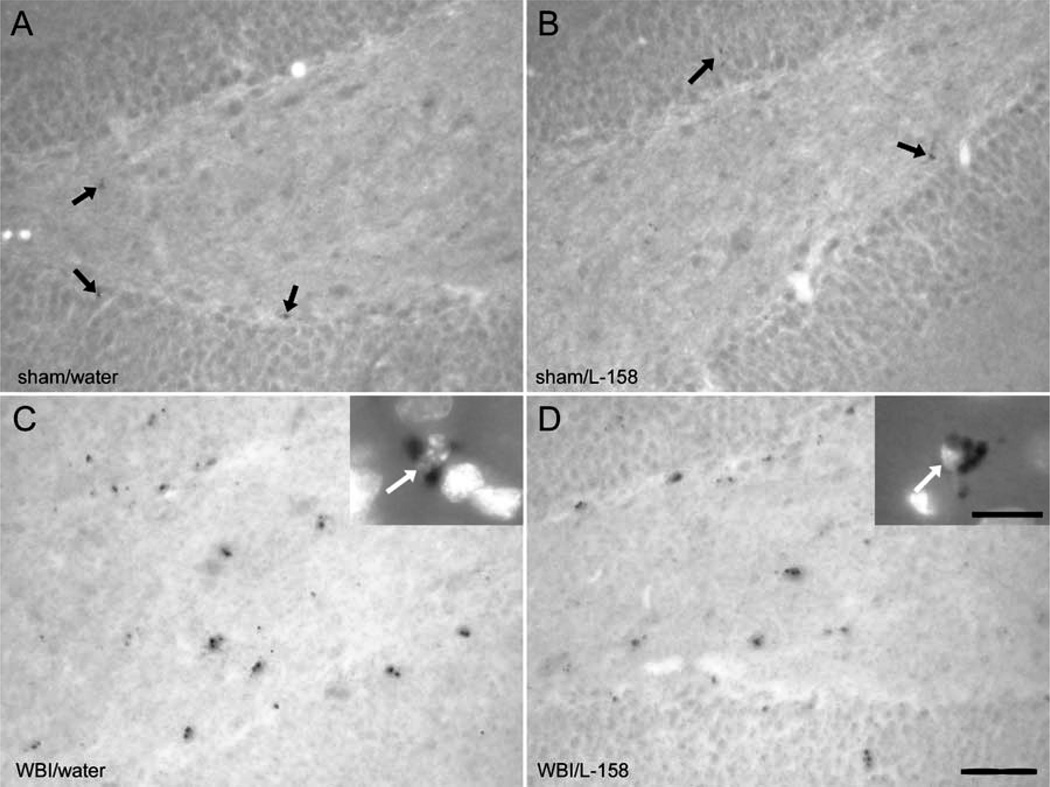

FIG. 2.

Immunolabeling of microglial activation in the DG. In the 1-week survival group, CD68-expressing cells, identified with the ED1 antibody, were rare and weakly labeled in sham-irradiated rats (arrows in panels A, B). ED1+ cells were abundant and more robustly labeled in irradiated (WBI) rats (panels C, D); DNA labeling (DAPI) confirmed that the ED1+ puncta surrounded small nuclei (arrows in insets of panels C and D). Scale bar = 50 µm (insets 8 µm).

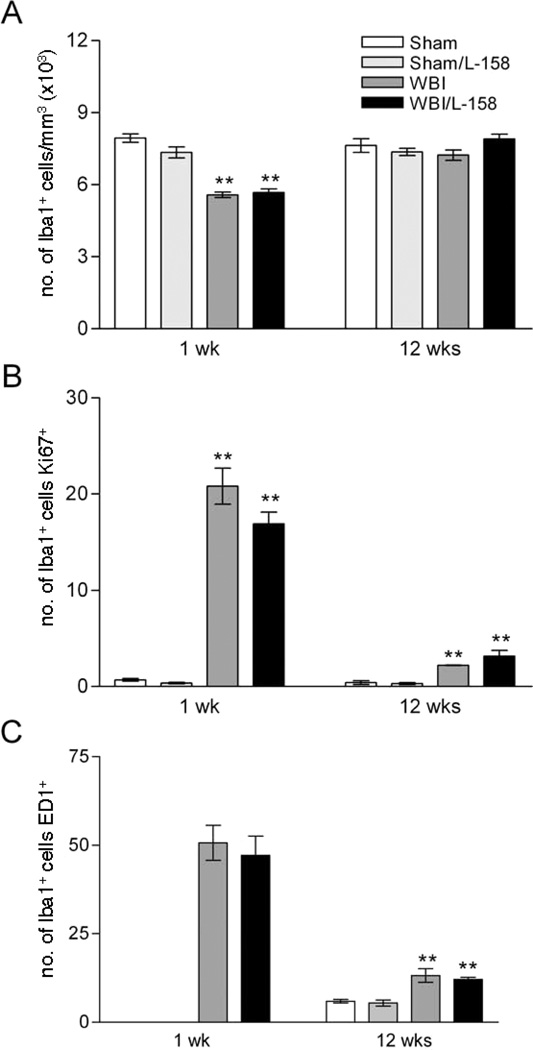

Quantitative analysis (Fig. 3A) demonstrated that the density of Iba1+ cells was reduced approximately 25% within the DG GCL/hilus of irradiated rats at 1 week [F(1,14) = 145.73, P < 0.001] but returned to the control level by 12 weeks. L-158,809 did not significantly affect microglial density at either time, although there were trends toward lower density in drug-treated sham-irradiated animals [condition × treatment interaction F(1,14) = 4.32, P = 0.06 at 1 week and F(1,14) = 3.62, P = 0.08 at 12 weeks]. Neither radiation nor L-158,809 treatment affected the mean volume of the DG GCL/hilus (sham irradiation: 6.01 ± 0.62, sham irradiation/L-158,809: 5.79 ± 0.50, whole-brain irradiation: 5.80 ± 0.48, whole-brain irradiation/L-158,809: 5.64 ± 0.40; mean ± SD in mm3).

FIG. 3.

Quantitative analysis of microglial density, proliferation and activation in the GCL/hilus. Whole-brain irradiation (WBI) significantly reduced the density of Iba1+ microglia in the GCL/hilus at 1 week but not at 12 weeks after irradiation (panel A). Despite the decrease in microglial density at 1 week, whole-brain irradiation increased the proportion of proliferating microglia (Ki67+/Iba1+ cells, panel B). Counts of ED1+ cells confirmed that whole-brain irradiation increased the proportion of activated microglia in the GCL/hilus at both survival times (activated microglia were too rare in sham-irradiated animals at 1 week to allow stereological quantification). L-158,809 treatment had no significant effect in sham-irradiated or irradiated rats. Values shown are means ± SEM for n = 5 animals per experimental group. **P < 0.001 compared to sham irradiation or sham irradiation/L-158,809 (Holm-Sidak).

Iba1+ cells expressing the proliferation marker Ki67 (Ki67+/Iba1+ cells, Fig. 1) were apparent in all animals but clearly were more abundant in irradiated rats. Most of the actively proliferating microglia bore extensive processes, and the Ki67+/Iba1+ population exhibited a range of morphologies similar to that seen in the Iba1+ population as a whole. To better assess proliferation within the changing microglial population, we analyzed the percentage of Iba1+ microglia that were proliferating (Ki67+, determined from sections double-labeled for Iba1 and Ki67). One week after irradiation, the percentage of dividing microglia (Fig. 3B) was less than 1% in sham-irradiated controls compared to 16–20% in irradiated animals [F(1,14) = 64.95, P < 0.001, confirmed by ANOVA on ranks]. Microglial proliferation was reduced to 2–3% of the total population at 12 weeks postirradiation but remained elevated in irradiated rats relative to sham-irradiated controls [F(1,15) = 48.43, P < 0.001, confirmed by ANOVA on ranks]. There was no effect of drug treatment on proliferating microglia at either survival time.

ED1 typically labeled individual or small groups of puncta near or surrounding the nucleus of labeled cells (Fig. 2C and D). As with Ki67/Iba1 labeling, qualitative assessment revealed a clear increase in ED1+ cells in irradiated rats but no apparent effect of L-158,809 treatment. At 1 week after irradiation, there were too few ED1-labeled cells in sham-irradiated animals for reliable analysis. In irradiated rats, treatment with L-158,809 did not change the density of ED1+ cells (whole-brain irradiation 2841 ± 681, whole-brain irradiation/L-158,809 2668 ± 675, mean ± SD per mm3) or the percentage of microglia (45–50%) that were ED1+ (estimated from the densities of Iba1+ cells and ED1+ cells, Fig. 3B). At 12 weeks after irradiation, ED1+ cells were sufficiently abundant in control animals to permit quantitative comparison among all experimental groups (sham irradiation 457 ± 96, sham irradiation/L-158,809 400 ± 140, whole-brain irradiation 932 ± 236, whole-brain irradiation/L-158,809 934 ± 76, mean ± SD per mm3). The percentage of ED1+ microglia (Fig. 3B) remained elevated in irradiated animals [12–13% after whole-brain irradiation compared to 5–6% in sham-irradiated controls, F(1,14) = 43.93, P < 0.001], although the magnitude of the radiation response at 12 weeks clearly was reduced compared to the 1-week survival time. L-158,809 treatment did not affect the percentage of activated microglia.

Effects of Whole-Brain Irradiation and AT1R Antagonism on Cell Proliferation and Neurogenesis in the SGZ

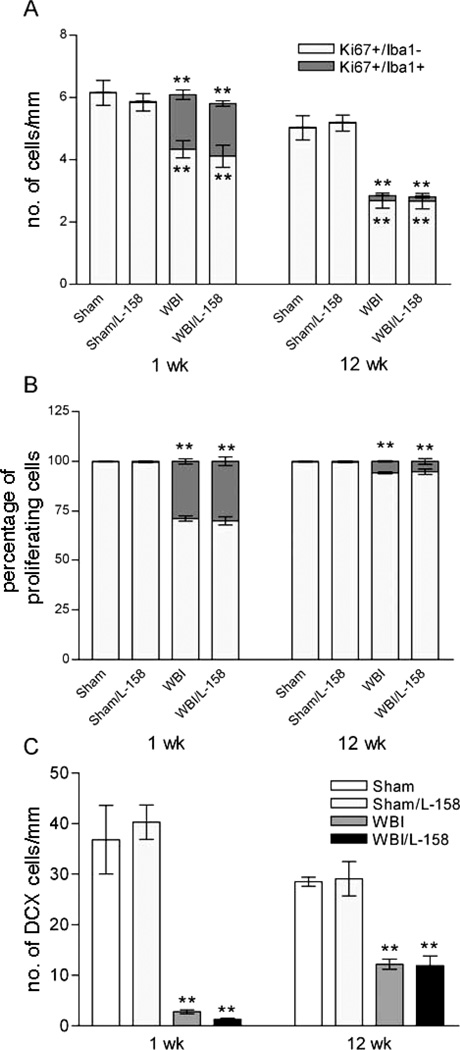

In the SGZ of the DG, we assessed the densities of proliferating microglia (Ki67+/Iba1+), proliferating non-microglial cells (Ki67+/Iba1−, presumptive neuronal progenitors), and neuroblasts/differentiating neurons (DCX+, Supplementary Fig. 2; http://dx.doi.org/10.1667/RR2560.1.S2). At 1 week after irradiation, counts of proliferating microglia and of presumptive neuronal progenitors demonstrated that the former increased dramatically (>50-fold) while the latter declined approximately 30% [Fig. 4A, Ki67+/Iba1+ F(1,27) = 86.99, P < 0.001, confirmed by ANOVA on ranks; Ki67+/Iba1− F(1,27) = 24.44, P < 0.001]. Within the population of proliferating cells in the SGZ, the fraction representing microglia increased substantially after irradiation while the fraction of neuronal progenitors decreased [Fig. 4B, F(1,27) = 86.65, P < 0.001; confirmed by ANOVA on ranks]. L-158,809 treatment had no effect on the radiation responses and no effect alone in sham-irradiated animals (Fig. 4A and B).

FIG. 4.

Effects of whole-brain irradiation (WBI) and AT1R antagonism on proliferation and neurogenesis in the SGZ. At both 1 and 12 weeks survival (panel A), whole-brain irradiation increased microglial proliferation (Ki67+/Iba1+) in the SGZ and decreased the density of proliferating, presumptive neuronal progenitor cells (Ki67+/Iba1−), significantly increasing the proportion of microglia within the population of proliferating cells (panel B). whole-brain irradiation also reduced the density of DCX+ cells at 1 week (panel C), with evidence of a partial recovery by 12 weeks. Values shown are means ± SEM for n = 5 animals per experimental group. **P < 0.001 compared to sham irradiation or sham irradiation/L-158,809 (Holm-Sidak).

At 12 weeks, the density of proliferating microglia remained higher in irradiated than in sham-irradiated rats [Fig. 4A, F(1,27) = 36.13, P < 0.001]; this radiation-induced increase was not affected by L-158,809. The densities of presumptive neuronal progenitors in irradiated rats were approximately half those in sham-irradiated controls, regardless of drug treatment [Fig. 4A; main effect whole-brain irradiation F(1,16) = 35.18, P < 0.001]. At 12 weeks postirradiation, radiation decreased the percentage of microglia and increased the percentage of non-microglial cells among the proliferating population. The radiation-induced change remained significant [F(1,27) = 36.13, P < 0.001] but appeared smaller at 12 weeks than at 1 week (Fig. 4B) and was not affected by drug treatment.

At 1 and 12 weeks after irradiation there were robust reductions in the density of neuroblasts/differentiating neurons in irradiated rats compared to sham-irradiated controls [Fig. 4C; whole-brain irradiation < 8% of sham at 1 week F(1,16) = 62.50, P < 0.001; whole-brain irradiation ~ 40% of sham irradiation at 12 weeks F(1,14) = 42.00, P < 0.001, confirmed by ANOVA on ranks]. Treatment with L-158,809 had no significant effect at either time. The experimental design did not support direct statistical comparisons between the two survival periods, but the density of immature neurons in sham-irradiated, control animals appeared to be reduced at 12 weeks compared to 1 week, presumably due to aging. Despite the approximately 25% aging-related decrease in sham-irradiated animals, the density of immature neurons in irradiated rats (regardless of drug treatment) was several fold higher at 12 weeks after irradiation than at 1 week.

DISCUSSION

RAAS blockade with L-158,809 prevents cognitive dysfunction in a rodent model of radiation-induced normal tissue injury (27), but the mechanisms are not clear. Demonstrations that RAAS blockade has anti-inflammatory effects in the lung and kidney (23, 47) and can modulate proliferation and neurogenesis in the brain (17, 26, 59) suggest possible mechanisms. In this and a previous study (16), we tested whether L-158,809 alleviates WBI-induced inflammation and/or rescues neurogenesis, neurobiological changes that have been implicated in experimental studies of WBI-induced cognitive dysfunction (7, 35). We reported previously that L-158,809 treatment did not alter neurogenesis or microglial markers of neuroinflammation at 6 and 12 months after fractionated irradiation (16) in a group of rats in which radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction was apparent and ameliorated by L-158,809 treatment (27). The observation that L-158,809 treatment for only a few weeks after fractionated irradiation also protected cognitive function (27) suggested that the drug’s benefits might involve earlier anti-inflammatory effects after irradiation; therefore, we tested effects of the drugs immediately and for several weeks after irradiation.

Cytokine Expression after Whole-Brain Irradiation and AT1R Antagonism

Cytokine expression increases after irradiation, peaking within 2 to 4 h and then typically returning to control levels by 24 h (46, 47, 49), a pattern similar to that seen after other nervous system injuries (48, 60–62). Although the most robust cytokine responses occur acutely after irradiation, longer-term cytokine changes also may occur (47). Moreover, drugs with anti-inflammatory efficacy may alter the time course as well as the extent of cytokine responses. We tested whether TNF-α or the other cytokines showed elevations in the hippocampus from 1 day to 12 weeks after a 10-Gy dose and found that radiation- and AT1RA-induced changes in cytokine expression at those times were small, consistent with previous reports of levels near controls by 24 h after irradiation (49). TNF-α expression was moderately suppressed by radiation at 1 day (presumably after a robust increase several hours earlier) (49); this decrease was observed with or without AT1RA treatment. Recovery of TNF-α expression to sham-irradiated levels at 1 week postirradiation was accompanied by decreased expression of IL-6, consistent with previous reports of feedback interactions between the two cytokines (63). As for TNF-α, the modest effects of radiation on IL-6 expression were not affected by the AT1RA. A radiation-induced increase in TNF-α expression at 12 weeks was significant only in rats that were not treated with L-158,809, suggesting the AT1RA modestly reduced a chronic, radiation-induced increase in TNF-α expression. Overall, however, this study revealed little effect of the AT1RA on cytokine expression at the level of the whole hippocampus in the period after the acute, peak cytokine response. Additional studies will be required to assess whether there is greater modulation of cytokines at the level of individual tissues or cells within the hippocampus.

Ang II Receptor Expression after Whole-Brain Irradiation and AT1R Antagonism

AT1R antagonism raises Ang II levels (27) and increases the availability of Ang II to bind to AT2R; thus an AT1RA may affect both receptors. In the present study, AT1aR mRNA expression was modestly increased in L-158,809-treated, sham-irradiated rats, consistent with upregulation in response to reduced ligand binding (64), but Western blot analysis in a separate group of rats did not reveal changes in the AT1R at the protein level. Drug treatment increased AT2R mRNA expression modestly when L-158,809 was combined with single-dose radiation, possibly due to increased availability of Ang II to the AT2R after AT1R blockade, since Ang II binding upregulates AT2R expression (65). Although upregulation of AT2R expression has been reported after a number of neural injuries and may have neuroprotective functions (17, 66), radiation alone did not alter its expression.

Microglial Responses to Whole-Brain Irradiation and AT1R Antagonism

Our cellular analysis of the inflammatory response focused on microglia in the DG, where radiation-induced changes in inflammatory cells and neuronal progenitors have been linked to cognitive deficits. In principle, the cells identified here as microglia may have included some peripherally derived macrophages; anti-Iba1 and other commonly used markers label both microglia and macrophages, and the cells develop common morphologies when highly activated. It is likely, however, that the Iba1+ population and proliferating and ED1+ cells within the Iba1+ population represented primarily, if not exclusively, intrinsic microglia. Although some investigators reported changes in the blood-brain barrier (BBB) in response to 10 Gy radiation (67, 68), a recent study demonstrated that brain irradiation at 10 Gy was not sufficient to result in migration of macrophage precursors from the periphery into the CNS (69).

Whole-brain irradiation, but not AT1R blockade, significantly altered microglial population dynamics in the hippocampus. At 1 week after irradiation, many more microglia were proliferating and/or activated in irradiated rats than in control animals, even though the total density of microglia was reduced [see also ref. (14)]. Greater proliferation in a smaller population indicates substantial microglial turnover in the days after irradiation (70). This increased proliferation at 1 week after irradiation was similar to that seen in other injury models (58, 70). radiation-induced microglial proliferation and activation (as seen by CD68 expression) remained elevated at 12 weeks, but the response was less robust than at 1 week, suggesting gradual stabilization of the microglia (at least with respect to markers typically assessed in studies of radiation-induced neural changes). Significantly, L-158,809 treatment had no effect on microglial proliferation or CD68 expression. This failure of AT1R blockade to modulate radiation-induced expression of CD68 is consistent with two recent reports that RAAS inhibition using the ACEi ramipril does not reduce the density of CD68+ cells in the DG SGZ of rats after 10 Gy irradiation, despite modest effects on neurogenesis (26, 71). The microglial indices assessed here, as in the ramipril studies (26, 71), were those most commonly used in studies of radiation-induced neuroinflammation. Additional studies will be required to assess other aspects of the microglial phenotype (e.g., production of anti-inflammatory signals and/or trophic factors) (72) that might provide a substrate for beneficial effects of the AT1RA on cognitive function.

Proliferation and Neurogenesis in Response to Whole-Brain Irradiation and AT1R Antagonism

Radiation-induced suppression of hippocampal neurogenesis is well documented (7, 33, 35, 73) and has been correlated with deficits in hippocampal-dependent cognitive tasks (74). Ang II receptors can influence cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation (17), so it is reasonable to expect that AT1R antagonism might modulate the radiation-induced deficits in proliferation and neurogenesis in the SGZ. In this study, as in previous ones (14, 43), radiation had no effect on the total number of proliferating cells in the SGZ at 1 week after irradiation. Phenotypic analysis of proliferating cells revealed, however, that at 1 week postirradiation increased proliferation of microglia (Ki67+/Iba1+) was similar in extent to decreased proliferation of non-microglial progenitors (Ki67+/Iba1−). The Ki67+/Iba1− population within the SGZ presumably represented primarily neuronal progenitors, and possibly a small population of macroglial progenitors (34, 75). Proliferation of the presumptive neuronal progenitor cells remained suppressed at 12 weeks after irradiation, when radiation-induced microglial proliferation was subsiding, resulting in an overall decrease in proliferation similar to that reported previously (43).

Radiation greatly reduced the density of neuroblasts and differentiating neurons (DCX+ cells). DCX provides an indirect index of the ongoing addition of neurons, since regulation of survival and integration may occur after cells become DCX+. This marker permitted us, however, to assess ongoing neuronal turnover in the same way at the 1- and 12-week survival times (1-week survival is insufficient to birth-date cells with bromodeoxyuridine and allow them to differentiate). Previous studies demonstrated directly that quantification of DCX-expressing cells provides an accurate assessment of changes in adult neurogenesis (56). In the present study, the density of DCX+ cells appeared to recover partially by 12 weeks after irradiation, even though proliferation of neuronal progenitor cells remained greatly suppressed. Thus there appears to be some capacity for spontaneous recovery of neurogenesis that involves mechanisms downstream of progenitor proliferation [this study and ref. (76)], in addition to recovery promoted by environmental enrichment (77) or exercise (78). The failure of L-158,809 treatment in the present study to protect or promote recovery of neurogenesis in irradiated rats or to alter neurogenesis in sham-irradiated controls stands in contrast to a report that RAAS inhibition with the ACEi ramipril slightly ameliorates a (10-Gy) radiation-induced reduction in DCX+ cells (and also decreases DCX+ cells in sham-irradiated controls) (26).

Drug Efficacy and Additional Mechanisms of Action

L-158,809 clearly reduces radiation-induced inflammation in the kidney and lung (23, 24) but had little ability to ameliorate the measures of radiation-induced neurobiological changes that were assessed here. Such results require consideration of the route of drug delivery, access to the CNS, and dosage, since all influence the ability to affect neural responses (79). Measurement of body weight and water/drug consumption throughout the course of this experiment confirmed that drug-treated rats consumed a consistent dose of L-158,809 and that the dose was not affected by radiation. We observed the same polydipsic effect of drug treatment seen in previous studies, demonstrating that the drug was active. As a class, nonpeptide Ang II antagonists share high lipophilia, which facilitates crossing of the BBB, and also have intermediate or better bioavailability after oral administration [reviewed in (32)]. L-158,809, specifically, has complete bioavailability after oral administration in rats (80) and a duration of action exceeding 6 h after a single oral dose (31). Although there are no specific analyses of the ability of L-158,809 to block AT1R in the CNS, several laboratories have demonstrated that drugs of this class cross the BBB, are distributed in the brain, and block AT1RA in the brain (81–85). Moreover, these drugs can be neuroprotective (86, 87) and, in some cases, such protection includes anti-inflammatory effects and/or reduction of oxidative stress (22, 88–90). Studies over two decades demonstrate directly that peripheral administration of AT1RA (orally, subcutaneously and/or intravenously; acutely or chronically) blocks effects of Ang II within the CNS (91–95). More specifically, two laboratories reported that systemic treatment with L-158,809 (acutely and at doses lower than that used here) reduced the effects of Ang II within the brain (96, 97). Finally, chronic treatment with L-158,809 as in the current study (20 mg/liter in drinking water) produced multiple changes in the brain RAAS that would counteract actions of Ang II (98). Taken together, this evidence supports the conclusion that L-158,809, as delivered in this study, reaches the brain and reduces Ang II signaling through the AT1R but does not modulate common neuroinflammatory markers and neurogenesis.

The absence of AT1RA-dependent modulation of inflammatory markers and neurogenesis leads one to consider other mechanisms that might contribute to the amelioration of radiation-induced cognitive deficits by L-158,809 (27). The complexity of the RAAS and the pleiotropic effects of drugs that target it suggest multiple targets for future investigation. RAAS inhibitors may modulate synaptic transmission through effects on Ang II receptors (99, 100). Modulation of the classical RAAS (AngII and AT1- and AT2R) also can alter signaling by the more recently identified angiotensin IV (AngIV)/AT4R system. The latter has been implicated in a variety of neural functions (e.g., cognitive processing, neural protection, plasticity and blood flow), with demonstrated effects on neuronal firing, long-term potentiation, learning and memory (101, 102). In addition to possible effects on neuronal signaling mediated by the AT1R and/or AT4R, decreased AT1R activity and increased AT2R activity in the presence of AT1R antagonists has been shown to promote cell differentiation (103). Thus AT1R blockade may promote the differentiation and integration of newborn neurons in the DG through effects on AT2R signaling. Further increasing the range of possible mechanisms of action, the brain RAAS may interact with other signaling systems that have been implicated in radiation-induced brain injury. A recent study demonstrated that beneficial effects of an AT1RA on cognitive function after chronic cerebral hypoperfusion are mediated in part through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) activation (104). PPAR-γ agonists, like AT1RAs, significantly improve cognitive measures in our rat model of radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction (105).

Summary

The AT1RA L-158,809 ameliorates cognitive impairment in young adult rats when measured 6 months or 1 year after fractionated whole-brain irradiation (27). It does not, however, alter the most extensively studied radiation-induced changes in the hippocampus, microglial proliferation and activation and hippocampal neurogenesis, either at the time cognitive changes appear after fractionated irradiation (16) or in the shorter term after single-dose irradiation (present study). Radiation-induced cognitive impairment likely involves multiple neurobiological changes that (1) may be independent of the inflammatory processes and altered cell turnover that have been implicated previously and (2) may be modulated by the brain RAAS and/or drugs that target the RAS. Given the robust, protective effects of RAAS inhibitors in our rodent model of radiation-induced brain injury, and their promise for reducing radiation-induced cognitive dysfunction in cancer patients, additional studies are required to elucidate and test the mechanisms of normal tissue injury that may contribute to cognitive dysfunction and that may be modulated by this class of drugs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ron Smith of Merck for kindly providing the L-158,809, Drs. Mike Robbins and Judy Brunso-Bechtold for helpful discussions, and Monica Paitsel for assistance in preparing the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants AG11370 (DRR), CA133483 (DRR) and NS056678 (KRC) and by the H. Parker Neuroscience Fund of Wake Forest University Health Sciences (DRR). The work was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree in the Program in Neuroscience, Wake Forest University School of Medicine (KRC).

Footnotes

Note. The online version of this article (DOI: 10.1667/RR2560.1) contains supplementary information that is available to all authorized users.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eichler AF, Loeffler JS. Multidisciplinary management of brain metastases. Oncologist. 2007;12:884–898. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silasi G, Diaz-Heijtz R, Besplug J, Rodriguez-Juarez R, Titov V, Kolb B, et al. Selective brain responses to acute and chronic low-dose X-ray irradiation in males and females. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:1223–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imperato JP, Paleologos NA, Vick NA. Effects of treatment on long-term survivors with malignant astrocytomas. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:818–822. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crossen JR, Garwood D, Glatstein E, Neuwelt EA. Neurobehavioral sequelae of cranial irradiation in adults: a review of radiation-induced encephalopathy. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:627–642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johannesen TB, Lien HH, Hole KH, Lote K. Radiological and clinical assessment of long-term brain tumour survivors after radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2003;69:169–176. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(03)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rola R, Raber J, Rizk A, Otsuka S, VandenBerg SR, Morhardt DR, et al. Radiation-induced impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis is associated with cognitive deficits in young mice. Exp Neurol. 2004;188:316–330. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monje ML, Toda H, Palmer TD. Inflammatory blockade restores adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science. 2003;302:1760–1765. doi: 10.1126/science.1088417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kempermann G, Neumann H. Neuroscience. Microglia: the enemy within? Science. 2003;302:1689–1690. doi: 10.1126/science.1092864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehninger D, Kempermann G. Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;331:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0478-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abayomi OK. Pathogenesis of irradiation-induced cognitive dysfunction. Acta Oncol. 1996;35:659–663. doi: 10.3109/02841869609083995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong CL, Gyato K, Awadalla AW, Lustig R, Tochner ZA. A critical review of the clinical effects of therapeutic irradiation damage to the brain: the roots of controversy. Neuropsych Rev. 2004;14:65–86. doi: 10.1023/b:nerv.0000026649.68781.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw EG, Robbins ME. The management of radiation-induced brain injury. Cancer Treat Res. 2006;128:7–22. doi: 10.1007/0-387-25354-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schindler MK, Forbes ME, Robbins ME, Riddle DR. Aging-dependent changes in the radiation response of the adult rat brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:826–834. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramanan S, Kooshki M, Zhao W, Hsu F-C, Riddle DR, Robbins ME. The PPARα agonist fenofibrate preserves hippocampal neurogenesis and inhibits microglial activation after whole-brain irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conner KR, Payne VS, Forbes ME, Robbins ME, Riddle DR. Effects of the AT1 receptor antagonist L-158,809 on microglia and neurogenesis after fractionated whole-brain irradiation. Radiat Res. 2010;173:49–61. doi: 10.1667/RR1821.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gendron L, Payet MD, Gallo-Payet N. The angiotensin type 2 receptor of angiotensin II and neuronal differentiation: from observations to mechanisms. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;31:359–372. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0310359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Culman J, Blume A, Gohlke P, Unger T. The renin-angiotensin system in the brain: possible therapeutic implications for AT(1)-receptor blockers. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:S64–S70. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen AM, Zhuo J, Mendelsohn FA. Localization and function of angiotensin AT1 receptors. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13:31S–38S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKinley MJ, Albiston AL, Allen AM, Mathai ML, May CN, McAllen RM, et al. The brain renin-angiotensin system: location and physiological roles. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:901–918. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00306-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez-Pallares J, Rey P, Parga JA, Muñoz A, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Brain angiotensin enhances dopaminergic cell death via microglial activation and NADPH-derived ROS. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31:58–73. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joglar B, Rodriguez-Pallares J, Rodriguez-Perez AI, Rey P, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. The inflammatory response in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease is mediated by brain angiotensin: relevance to progression of the disease. J Neurochem. 2009;109:656–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molteni A, Moulder JE, Cohen EF, Ward WF, Fish BL, Taylor JM, et al. Control of radiation-induced pneumopathy and lung fibrosis by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker. Int J Radiat Biol. 2000;76:523–532. doi: 10.1080/095530000138538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen EP, Fish BL, Moulder JE. The renin-angiotensin system in experimental radiation nephropathy. J Lab Clin Med. 2002;139:251–257. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2002.122279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JH, Brown SL, Kolozsvary A, Jenrow KA, Ryu S, Rosenblum ML, et al. Modification of radiation injury by ramipril, inhibitor of angiotensin-converting enzyme, on optic neuropathy in the rat. Radiat Res. 2004;161:137–142. doi: 10.1667/rr3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenrow KA, Brown SL, Liu J, Kolozsvary A, Lapanowski K, Kim JH. Ramipril mitigates radiation-induced impairment of neurogenesis in the rat dentate gyrus. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robbins ME, Payne V, Tommasi E, Diz DI, Hsu FC, Brown WR, et al. The AT1 receptor antagonist, L-158,809, prevents or ameliorates fractionated whole-brain irradiation-induced cognitive impairment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robbins ME, Zhao W, Garcia-Espinosa MA, Diz DI. Renin-angiotensin system blockers and modulations of radiation-induced brain injury. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:1413–1422. doi: 10.2174/1389450111009011413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washida K, Ihara M, Nishio K, Fujita Y, Maki T, Yamada M, et al. Nonhypotensive dose of telmisartan attenuates cognitive impairment partially due to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation in mice with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Stroke. 2010;41:1798–1806. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Igic R, Behnia R. Properties and distribution of angiotensin I converting enzyme. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:697–706. doi: 10.2174/1381612033455459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siegl PK, Chang RS, Mantlo NB, Chakravarty PK, Ondeyka DL, Greenlee WJ, et al. In vivo pharmacology of L-158,809, a new highly potent and selective nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Csajka C, Buclin T, Brunner HR, Biollaz J. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic profile of angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:1–29. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monje ML, Mizumatsu S, Fike JR, Palmer TD. Irradiation induces neural precursor-cell dysfunction. Nat Med. 2002;8:955–962. doi: 10.1038/nm749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizumatsu S, Monje ML, Morhardt DR, Rola R, Palmer TD, Fike JR. Extreme sensitivity of adult neurogenesis to low doses of X-irradiation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4021–4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raber J, Rola R, LeFevour A, Morhardt D, Curley J, Mizumatsu S, et al. Radiation-induced cognitive impairments are associated with changes in indicators of hippocampal neurogenesis. Radiat Res. 2004;162:39–47. doi: 10.1667/rr3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villasana L, Acevedo S, Poage C, Raber J. Sex- and APOE isoform-dependent effects of radiation on cognitive function. Radiat Res. 2006;166:883–891. doi: 10.1667/RR0642.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winocur G, Wojtowicz JM, Sekeres M, Snyder JS, Wang S. Inhibition of neurogenesis interferes with hippocampus-dependent memory function. Hippocampus. 2006;16:296–304. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Acevedo SE, McGinnis G, Raber J. Effects of 137Cs gamma irradiation on cognitive performance and measures of anxiety in Apoe−/− and wild-type female mice. Radiat Res. 2008;170:422–428. doi: 10.1667/rr1494.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Acharya MM, Christie LA, Lan ML, Donovan PJ, Cotman CW, Fike JR, et al. Rescue of radiation-induced cognitive impairment through cranial transplantation of human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19150–19155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909293106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu KL, Tu B, Li YQ, Wong CS. Role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in radiation-induced brain injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu JL, Tian DS, Li ZW, Qu WS, Zhan Y, Xie MJ, et al. Tamoxifen alleviates irradiation-induced brain injury by attenuating microglial inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2010;1316:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peissner W, Kocher M, Treuer H, Gillardon F. Ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis of proliferating stem cells in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;71:61–68. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tada E, Parent J, Lowenstein D, Fike JR. X-irradiation causes a prolonged reduction in cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of adult rats. Neuroscience. 2000;99:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dagenais NJ, Jamali F. Protective effects of angiotensin II interruption: evidence for antiinflammatory actions. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:1213–1229. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.9.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lanz TV, Ding Z, Ho PP, Luo J, Agrawal AN, Srinagesh H, et al. Angiotensin II sustains brain inflammation in mice via TGF-beta. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2782–2794. doi: 10.1172/JCI41709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hong JH, Chiang CS, Campbell IL, Sun JR, Withers HR, McBride WH. Induction of acute phase gene expression by brain irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:619–626. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiang CS, Hong JH, Stalder A, Sun JR, Withers HR, McBride WH. Delayed molecular responses to brain irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 1997;72:45–53. doi: 10.1080/095530097143527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaber MW, Sabek OM, Fukatsu K, Wilcox HG, Kiani MF, Merchant TE. Differences in ICAM-1 and TNF-alpha expression between large single fraction and fractionated irradiation in mouse brain. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:359–366. doi: 10.1080/0955300031000114738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee WH, Sonntag WE, Mitschelen M, Yan H, Lee YW. Irradiation induces regionally specific alterations in pro-inflammatory environments in rat brain. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010;86:132–144. doi: 10.3109/09553000903419346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 4th ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deng X, Li H, Tang YW. Cytokine expression in respiratory syncytial virus-infected mice as measured by quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR. J Virol Methods. 2003;107:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kee N, Sivalingam S, Boonstra R, Wojtowicz JM. The utility of Ki-67 and BrdU as proliferative markers of adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ito D, Imai Y, Ohsawa K, Nakajima K, Fukuuchi Y, Kohsaka S. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;57:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Damoiseaux JG, Dopp EA, Calame W, Chao D, MacPherson GG, Dijkstra CD. Rat macrophage lysosomal membrane antigen recognized by monoclonal antibody ED1. Immunology. 1994;83:140–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown JP, Couillard-Despres S, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Winkler J, Aigner L, Kuhn HG. Transient expression of doublecortin during adult neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:1–10. doi: 10.1002/cne.10874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Couillard-Despres S, Winner B, Schaubeck S, Aigner R, Vroemen M, Weidner N, et al. Doublecortin expression levels in adult brain reflect neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB, Kieu K, Nielsen J. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology—reconsidered. J Microsc. 1999;193:199–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1999.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Streit WJ, Walter SA, Pennell NA. Reactive microgliosis. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;57:563–581. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki Y, Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Esteban V, Egido J. Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2003;35:881–900. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Streit WJ, Semple-Rowland SL, Hurley SD, Miller RC, Popovich PG, Stokes BT. Cytokine mRNA profiles in contused spinal cord and axotomized facial nucleus suggest a beneficial role for inflammation and gliosis. Exp Neurol. 1998;152:74–87. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gregersen R, Lambertsen K, Finsen B. Microglia and macrophages are the major source of tumor necrosis factor in permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:53–65. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200001000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tanaka S, Ide M, Shibutani T, Ohtaki H, Numazawa S, Shioda S, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation induces learning and memory deficits without neuronal cell death in rats. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:557–566. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feghali CA, Wright TM. Cytokines in acute and chronic inflammation. Front Biosci. 1997;2:d12–d26. doi: 10.2741/a171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolf G, Ritz E. Combination therapy with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers to halt progression of chronic renal disease: pathophysiology and indications. Kidney Int. 2005;67:799–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shibata K, Makino I, Shibaguchi H, Niwa M, Katsuragi T, Furukawa T. Up-regulation of angiotensin type 2 receptor mRNA by angiotensin II in rat cortical cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:633–637. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Makino I, Shibata K, Ohgami Y, Fujiwara M, Furukawa T. Transient upregulation of the AT2 receptor mRNA level after global ischemia in the rat brain. Neuropeptides. 1996;30:596–601. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(96)90043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Diserbo M, Agin A, Lamproglou I, Mauris J, Staali F, Multon E, et al. Blood-brain barrier permeability after gamma whole-body irradiation: an in vivo microdialysis study. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:670–678. doi: 10.1139/y02-070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li YQ, Chen P, Jain V, Reilly RM, Wong CS. Early radiation-induced endothelial cell loss and blood-spinal cord barrier breakdown in the rat spinal cord. Radiat Res. 2004;161:143–152. doi: 10.1667/rr3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, Tetzlaff W, Rossi FM. Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1538–1543. doi: 10.1038/nn2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ladeby R, Wirenfeldt M, Garcia-Ovejero D, Fenger C, Dissing-Olesen L, Dalmau I, et al. Microglial cell population dynamics in the injured adult central nervous system. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jenrow KA, Liu J, Brown SL, Kolozsvary A, Lapanowski K, Kim JH. Combined atorvstatin and ramipril mitigate radiation-induced impairment of dentate gyrus neurogenesis. J Neurooncol. 2011;101:449–456. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0282-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakajima K, Kohsaka S. Microglia: neuroprotective and neurotrophic cells in the central nervous system. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2004;4:65–84. doi: 10.2174/1568006043481284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Madsen TM, Kristjansen PE, Bolwig TG, Wortwein G. Arrested neuronal proliferation and impaired hippocampal function following fractionated brain irradiation in the adult rat. Neuroscience. 2003;119:635–642. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Monje ML, Palmer T. Radiation injury and neurogenesis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:129–134. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000063772.81810.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Andres-Mach M, Rola R, Fike JR. Radiation effects on neural precursor cells in the dentate gyrus. Cell Tissue Res. 331:251–262. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0480-9. 200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ben Abdallah NM, Slomianka L, Lipp HP. Reversible effect of X-irradiation on proliferation, neurogenesis, and cell death in the dentate gyrus of adult mice. Hippocampus. 2007;17:1230–1240. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fan Y, Liu Z, einstein PR, Fike JR, Liu J. Environmental enrichment enhances neurogenesis and improves functional outcome after cranial irradiation. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Naylor AS, Bull C, Nilsson MK, Zhu C, Björk-Eriksson T, Eriksson PS, et al. Voluntary running rescues adult hippocampal neurogenesis after irradiation of the young mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14632–14637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711128105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Unger T. Inhibiting angiotensin receptors in the brain: possible therapeutic implications. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:449–451. doi: 10.1185/030079903125001974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Colletti AE, Krieter PA. Disposition of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist L-158,809 in rats and rhesus monkeys. Drug Metab Dispos. 1994;22:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Polidori C, Ciccocioppo R, Pompei P, Cirillo R, Massi M. Functional evidence for the ability of angiotensin AT1 receptor antagonists to cross the blood-brain barrier in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;307:259–267. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Polidori C, Ciccocioppo R, Nisato D, Cazaubon C, Massi M. Evaluation of the ability of irbesartan to cross the blood-brain barrier following acute intragastric treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;352:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Davi H, Tronquet C, Miscoria G, Perrier L, DuPont P, Caix J, et al. Disposition of irbesartan, an angiotensin II AT1-receptor antagonist, in mice, rats, rabbits, and macaques. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nishimura Y, Ito T, Hoe K, Saavedra JM. Chronic peripheral administration of the angiotensin II AT(1) receptor antagonist candesartan blocks brain AT(1) receptors. Brain Res. 2000;871:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pavlatou MG, Mastorakos G, Lekakis I, Liatis S, Vamvakou G, Zoumakis E, et al. Chronic administration of an angiotensin II receptor antagonist resets the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and improves the affect of patients with diabetes mellitus type 2: preliminary results. Stress. 2008;11:62–72. doi: 10.1080/10253890701476621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thone-Reineke C, Zimmermann M, Neumann C, Krikov M, Li J, Gerova N, Unger T. Are angiotensin receptor blockers neuroprotective? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2004;6:257–266. doi: 10.1007/s11906-004-0019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saavedra JM, Ando H, Armando I, Baiardi G, Bregonzio C, Juorio A, et al. Anti-stress and anti-anxiety effects of centrally acting angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists. Regul Pept. 2005;128:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lou M, Blume A, Zhao Y, Gohlke P, Deuschl G, Herdegen T, et al. Sustained blockade of brain AT1 receptors before and after focal cerebral ischemia alleviates neurologic deficits and reduces neuronal injury, apoptosis, and inflammatory responses in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:536–547. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200405000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jung KH, Chu K, Lee ST, Kim SJ, Song EC, Kim EH, et al. Blockade of AT1 receptor reduces apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress in normotensive rats with intracerebral hemorrhage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:1051–1058. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.120097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ozacmak VH, Sayan H, Cetin A, Akyildiz-Igdem A. AT1 receptor blocker candesartan-induced attenuation of brain injury of rats subjected to chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1314–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wayner MJ, Armstrong DL, Polan-Curtain JL, Denny JB. Role of angiotensin II and AT1 receptors in hippocampal LTP. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;45:455–464. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90265-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gohlke P, Kox T, Jürgensen T, von Kügelgen S, Rascher W, Unger T, et al. Peripherally applied candesartan inhibits central responses to angiotensin II in conscious rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2002;365:477–483. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0545-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gohlke P, Von Kügelgen S, Jürgensen T, Kox T, Rascher W, Culman J, et al. Effects of orally applied candesartan cilexetil on central responses to angiotensin II in conscious rats. J Hypertens. 2002;20:909–918. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200205000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Seltzer A, Bregonzio C, Armando I, Baiardi G, Saavedra JM. Oral administration of an AT1 receptor antagonist prevents the central effects of angiotensin II in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Brain Res. 2004;1028:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saavedra JM, Benicky J, Zhou J. mechanisms of the anti-ischemic effect of angiotensin II AT(1) receptor antagonists in the brain. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:1099–1111. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9009-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu JL, Murakami H, Sanderford M, Bishop VS, Zucker IH. ANG II and baroreflex function in rabbits with CHF and lesions of the area postrema. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H342–H350. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.1.H342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Scheuer DA, Bechtold AG. Glucocorticoids potentiate central actions of angiotensin to increase arterial pressure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R1719–R1726. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.6.R1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gilliam-Davis S, Gallagher PE, Payne VS, Kasper SO, Tommasi EN, Robbins MC, et al. Long-term systemic renin-angiotensin system blockade alters expression of renin-angiotensin system components in dorsomedial medulla of Fischer 344 rats. Hypertension. 2008;52:E61. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wright JW, Harding JW. Brain angiotensin receptor subtypes in the control of physiological and behavioral responses. Neuroscience and Biobehav Rev. 1994;18:21–53. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pan HL. Brain angiotensin II and synaptic transmission. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:422–431. doi: 10.1177/1073858404264678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wright JW, Reichert JR, Davis CJ, Harding JW. Neural plasticity and the brain renin-angiotensin system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:529–552. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wright JW, Yamamoto BJ, Harding JW. Angiotensin receptor subtype mediated physiologies and behaviors: new discoveries and clinical targets. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84:157–181. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Unger T. The angiotensin type 2 receptor: variations on an enigmatic theme. J Hypertens. 1999;17:1775–1786. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917121-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Washida K, Ihara M, Nishio K, Fujita Y, Maki T, Yamada M, et al. Nonhypotensive dose of telmisartan attenuates cognitive impairment partially due to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation in mice with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Stroke. 2010;41:1798–1806. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhao W, Payne V, Tommasi E, Diz DI, Hsu FC, Robbins ME. Administration of the peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist pioglitazone during fractionated brain irradiation prevents radiation-induced cognitive impairment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.