Abstract

Neuropathic pain is a debilitating condition that is often difficult to treat using conventional pharmacological interventions and the exact mechanisms involved in the establishment and maintenance of this type of chronic pain have yet to be fully elucidated. The present studies examined the effect of chronic nerve injury on μ-opioid receptors and receptor-mediated G-protein activity within the supraspinal brain regions involved in pain processing of mice. Chronic constriction injury (CCI) reduced paw withdrawal latency, which was maximal at 10 days post-injury. [d-Ala2,(N-Me)Phe4, Gly5-OH] enkephalin (DAMGO)-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was then conducted at this time point in membranes prepared from the rostral ACC (rACC), thalamus and periaqueductal grey (PAG) of CCI and sham-operated mice. Results showed reduced DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the thalamus and PAG of CCI mice, with no change in the rACC. In thalamus, this reduction was due to decreased maximal stimulation by DAMGO, with no difference in EC50 values. In PAG, however, DAMGO Emax values did not significantly differ between groups, possibly due to the small magnitude of the main effect. [3H]Naloxone binding in membranes of the thalamus showed no significant differences in Bmax values between CCI and sham-operated mice, indicating that the difference in G-protein activation did not result from differences in μ-opioid receptor levels. These results suggest that CCI induced a region-specific adaptation of μ-opioid receptor-mediated G-protein activity, with apparent desensitization of the μ-opioid receptor in the thalamus and PAG and could have implications for treatment of neuropathic pain.

Keywords: neuropathic pain, μ-opioid receptor, thalamus, anterior cingulate cortex, PAG

1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain is a chronic pain state characterized by hyperalgesia, allodynia and stimulus-independent pain (Jensen et al., 2001) that results from disease, trauma or infection. This type of pain is often rated as more severe than other chronic pain conditions and less responsive to traditional pharmacological approaches such as opioids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Khoromi et al., 2007; Dworkin et al., 2010). However, the exact mechanisms that contribute to these characteristics of neuropathic pain have not been well defined.

μ-Opioid receptors are expressed in brain regions that modulate nociception, including the anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus and periaqueductal grey (PAG) (Wang et al., 2009). Additionally, the ACC, thalamus and PAG have functional anatomical connections and have been shown to be involved in the establishment and maintenance of chronic pain states. Several thalamic nuclei have been shown to be involved in processing of nociceptive information and have multiple connections to the ACC (Hsu et al., 2000; Kung and Shyu, 2002) and the PAG has direct connections to both medial and lateral thalamic nuclei (Krout and Loewy, 2000). Additionally, the PAG and thalamus receive descending input from the ACC, amongst many other cortical areas (Bragin et al., 1984). The coordinated output from these regions modulates the perception of pain.

Lesioning or direct pharmacological manipulation of these interconnected neuroanatomical areas has been shown to affect pain behaviors in human and animal models. Direct chemical or electrolytic lesions of thalamic nuclei were reported to decrease neuropathic pain-like behaviors in the rat (Saade et al., 2007) and alleviate chronic intractable pain in humans (Jeanmonod et al., 1994; Uematsu et al., 1974; Young et al., 1995). Similarly, lesions of the ACC reduced chronic pain in humans via reduction in the negative affect associated with the experience of pain (Cohen et al., 1999; Foltz and White, 1968; Hurt and Ballantine, 1974). Additionally, the ACC, thalamus and PAG are involved in μ-opioid mediated pain suppression. Morphine injected directly into the PAG or medial thalamic nuclei has been shown to produce antinociception and suppress affective reactions to noxious stimuli (Carr and Bak, 1988; Harte et al., 2000; Yeung et al., 1977; Yeung et al., 1978) and fMRI studies have shown that activation of the ACC induced by noxious stimuli is suppressed in rats following systemic morphine administration (Chang and Shyu, 2001; Tuor et al., 2000). Therefore, it is possible that pathophysiological changes in supraspinal μ-opioid receptors might contribute to the symptomology of the disease and impact potential treatment, but the effect of neuropathic pain on μ-opioid receptor function in these CNS regions has not been well defined.

Previous studies showed that sciatic nerve ligation in the mouse decreased μ-opioid stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the amygdala and ventral midbrain (including the ventral tegmental area), that was associated with anxiety and reduced morphine-mediated place preference, respectively (Narita et al., 2006; Ozaki et al., 2003), However, the effect of neuropathic pain on μ-opioid-mediated G-protein activity in brain areas directly involved in nociceptive processing has not been thoroughly examined. Therefore, the present study was conducted to assess the effect of chronic constriction injury (CCI) on receptor-mediated G-protein activity in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC), thalamus and PAG, in order to determine whether μ-opioid receptors in these pain modulatory areas undergo adaptation during neuropathic pain states.

2. Results

2.1 Thermal Hyperalgesia Induced by CCI

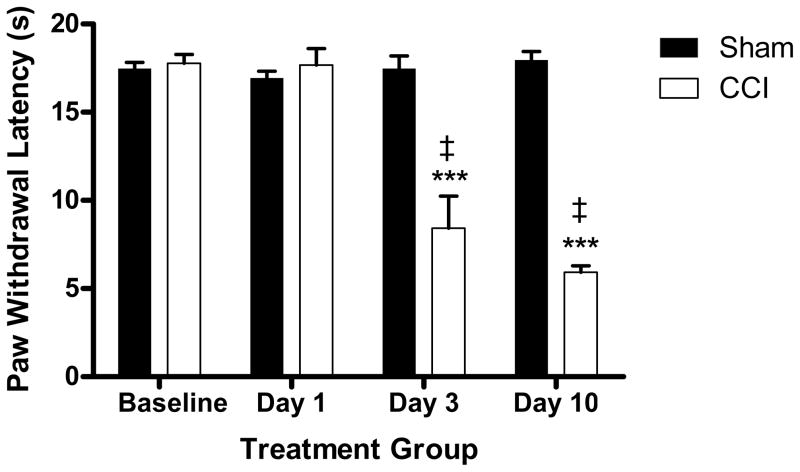

In vivo studies were first conducted to determine the effect of CCI on paw withdrawal. Results showed that sciatic nerve ligation produced an approximately 75% reduction in paw withdrawal latency to thermal stimulation in the ipsilateral paw of CCI mice when compared to sham-operated controls. Differences in paw withdrawal latency between CCI and sham-operated mice were significant at days 3 (p < 0.001, t=4.653) and 10 (p < 0.0001, t=20.32) post-surgery (Figure 1). Additionally, CCI-operated mice also showed significant within group differences in pain hypersensitivity at day 3 (p <0.0001, t=6.831) and day 10 (p < 0.0001, t=18.27) -post CCI when compared to their pre-surgical baseline latencies (Figure 1). Since differences in withdrawal latencies were greatest at day 10 post-surgery, this time point was selected for all binding experiments, unless otherwise noted.

Figure 1.

Sciatic nerve ligation produced a significant reduction in paw withdrawal latency to thermal stimulus in the ipsilateral paw of CCI mice when compared to sham- operated controls. This effect was observed at day 3 and day 10 post surgery, but not at day 1. (***p < 0.001 CCI vs. sham, ‡p < 0.0001 CCI vs. baseline, n = 5–6 per group)

2.2 DAMGO-Stimulated [35S]GTPγS Binding

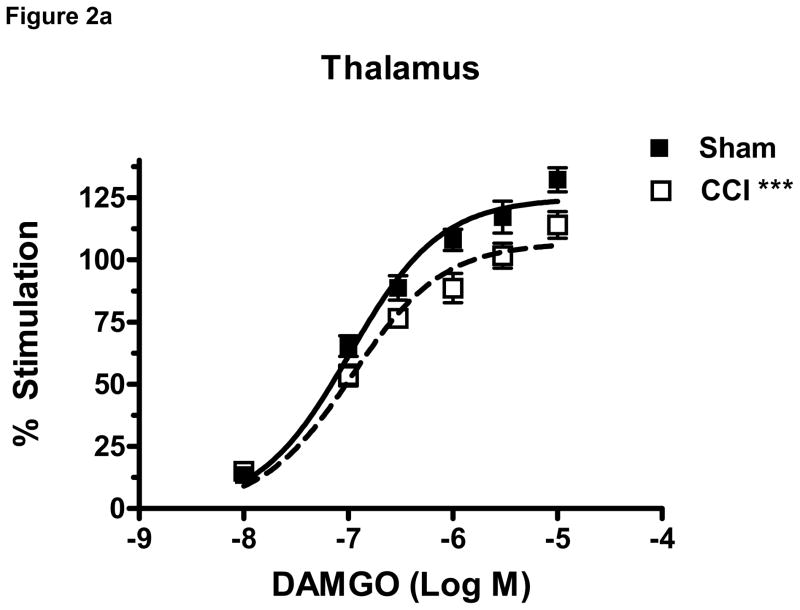

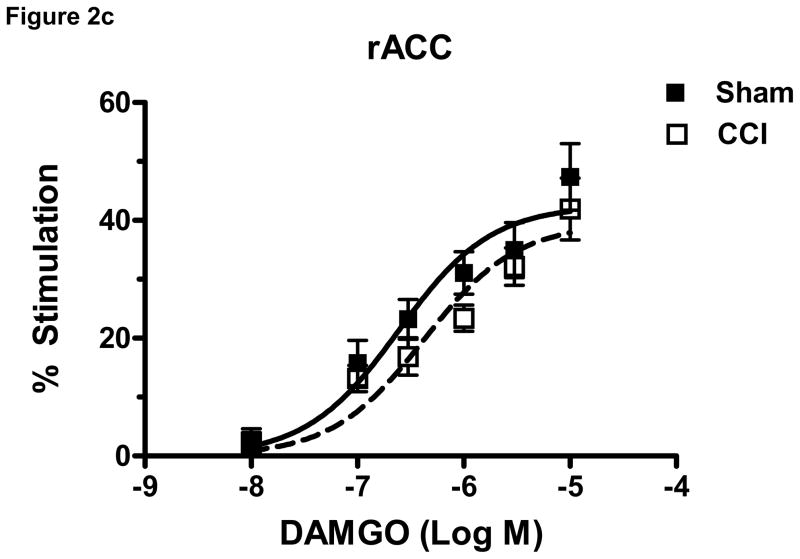

To determine the effect of CCI on μ-opioid receptor-mediated G-protein activity in brain regions relevant to nociception, DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was conducted in membranes prepared from the rACC, thalamus and PAG of CCI and sham- operated mice at day 10 post surgery. DAMGO produced a concentration-dependent stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding in both CCI and sham groups in all brain areas examined (Figure 2a–c). Two-way ANOVA of the of DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in each brain region demonstrated a significant effect of CCI in the thalamus (p< 0.0001, F= 22.51, df= 1) (Figure 2a) and PAG (p< 0.0001, F= 20.80, df= 1) (Figure 2b), but no significant effect of CCI in the rACC (p= 0.0545, F= 3 .886, df= 1)(Figure 2c). Further analysis of the concentration-effect data was conducted by non-linear regression curve fitting to obtain DAMGO Emax and EC50 values. Results showed that the Emax value for DAMGO to stimulate [35S]GTPγS binding was significantly decreased by 14.6 ± 4.2% in the thalamus of CCI mice when compared to sham mice (p < 0.05, t= 2.525) (Table 1). In contrast, there were no significant differences in Emax values between sham and CCI mice in the PAG (p= 0.41) or rACC (p= 0. 42) (Table 1). The EC50 values for DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding did not differ between CCI and sham operated mice in any brain region examined (Table 1). Basal [35S]GTPγS binding, measured in the absence of agonist, did not differ between sham and CCI groups in either rACC or thalamus. However, there was a significant decrease from 117 ± 4.5 to 97 ± 6.3 fmol/mg (p < 0.05, t=2.529) in the PAG of CCI compared to sham operated mice (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Data are expressed as percent net stimulated binding above basal binding. DAMGO (10−5–10−8 M) produced a concentration dependent increase in binding in both CCI and sham groups in all brain areas (2a–c). CCI surgery induced a significant effect of DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS in the thalamus (a) and PAG (b) but not in the rACC (c) of mice when compared to sham operated controls at day 10 post surgery. (***p< 0.0001, n = 6 per group)

Table 1.

Emax, EC50, and basal binding values from DAMGO-stimulated [35S] GTPγS binding in brain areas of the mouse at day 10 post-surgery.

| Region | Sham | CCI |

|---|---|---|

| rACC | ||

| Emax (% stimulation) | 42.74 ± 4.388 | 39.33 ± 4.362 |

| EC50 (μM) | 0.280 ± 0.069 | 0.441 ± 0.099 |

| Basal (fmol/mg) | 128.6 ± 17.04 | 136.3 ± 18.89 |

| Thalamus | ||

| Emax (% stimulation) | 127.2 ± 5.010 | 108.6 ± 5.408* |

| EC50 (μM) | 0.130 ± 0.010 | 0.132 ± 0.016 |

| Basal (fmol/mg) | 138.5 ± 6.629 | 147.1 ± 7.963 |

| PAG | ||

| Emax (% stimulation) | 139.3 ± 8.166 | 127.9 ± 3.811 |

| EC50 (μM) | 0.139 ± 0.015 | 0.124 ± 0.012 |

| Basal (fmol/mg) | 117.1 ± 4.557 | 97.4 ± 6.296* |

The Emax value of DAMGO was significantly decreased in the thalamus of CCI relative to sham mice only on day 10 (*p< 0.05). Data are expressed as group means ± S.E.M of six mice per group.

Considering the significant decrease in Emax values in the thalamus following CCI surgery it was of interest to determine the time point at which this difference developed. Therefore, two additional groups of mice were treated and thalamic membranes were harvested at either day 1 or day 3 post surgery and examined via DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding. Two-way ANOVA of the of the concentration-effect curves in thalamus demonstrated no significant effect of CCI at day 1 (p = 0.5235, F= 0.4118, df= 1) or day 3 (p= 0.2133, F= 1.586, df= 1) (curves not shown) post-surgery. Further analysis of curve-fit values showed that the Emax and EC50 values of DAMGO did not differ significantly between CCI and sham mice on days 1 or 3 post surgery (Table 2).

Table 2.

Emax and EC50 values from DAMGO-stimulated [35S] GTPγS binding in thalamic tissue of mice at days 1 and 3 post-surgery.

| Day | Sham | CCI |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | ||

| Emax(% stimulation) | 74.07 ± 5.069 | 73.58 ± 2.880 |

| EC50(μM) | 0.159 ± 0.026 | 0.179 ± 0.033 |

| Day 3 | ||

| Emax(% stimulation) | 75.30 ± 3.634 | 74.16 ± 8.859 |

| EC50(μM) | 0.087 ± 0.009 | 0.121 ± 0.020 |

Data are expressed as group means ± S.E.M of five-six mice per group.

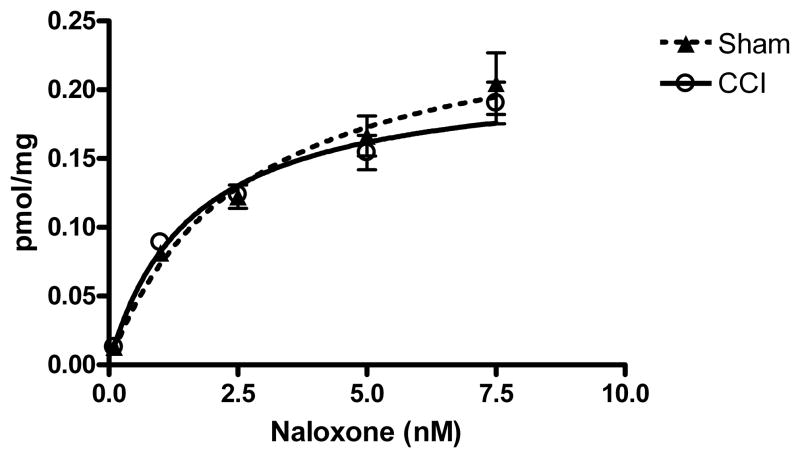

2.3 Opioid Receptor Binding

In order to determine whether the CCI-induced decrease in DAMGO-stimulated [35S] GTPγS binding in the thalamus was due to desensitization or down-regulation of μ-opioid receptors, [3H]naloxone binding was conducted. No significant differences in the Bmax (p= 0.19, t=1.384, df=10) or KD (p= 0.11, t=1.760, df=10) values for [3H]naloxone binding were found in the thalamus of CCI versus sham mice at 10 days post-surgery (Figure 3). This finding showed that there were no differences in overall μ-opioid receptor density between CCI and sham operated mice.

Figure 3.

[3H] naloxone receptor binding was conducted on the thalamus at day 10 post CCI surgery. There were no significant differences in binding between CCI (Bmax 0.2072 ± 0.01983; KD =1.50 ± 0.275) and sham (Bmax = 0.2659 ± 0.0375, KD = “2.65 ± 0.595) mice in the thalamus. Data are expressed as group means ± S.E.M. (n = 6).

3. Discussion

The findings of this study revealed region-dependent adaptations of μ-opioid receptors in response to CCI, a model of neuropathic pain. μ-Opioid receptor-mediated G-protein activity was reduced in the thalamus and PAG of CCI mice, indicating an apparent desensitization of receptors in these regions. This attenuation in μ-opioid receptor activity in thalamus of CCI mice was due to a decrease in maximal stimulation by the agonist. The potential functional importance of neuroadaptation in the thalamus is suggested by the multiple connections that many thalamic nuclei have to both the medial and lateral pain pathways, as well as to the limbic system. There was no significant difference in μ-opioid receptor mediated activity in the rACC of CCI relative to sham-operated mice, and the magnitude of the difference in PAG was modest, such that no difference in DAMGO Emax values could be detected. Moreover, there was also a significant decrease in basal [35S]GTPγS binding levels in the PAG of CCI mice. This effect in the PAG did not reach the level of significance in our previous study, which examined differences in cannabinoid stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding following CCI (Hoot et al.). This modest apparent difference could be due to various factors, such as differences in basal G-protein-coupled receptor activity or G-protein expression levels, but does not appear to be critical to the chronic pain state as the magnitude of the CCI induced hyperalgesia did not differ between these two studies.

Region-specific adaptations of the μ-opioid receptor have previously been demonstrated in other brain areas. For example, Ozaki et al.(Ozaki et al., 2003) found reduced μ-opioid receptor-mediated G-protein activity in the ventral midbrain, with no change in limbic forebrain or pons/medulla. Region-specific changes have also been found in cannabinoid receptor 1-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in response to CCI, with desensitization found in the rACC, but not in PAG or thalamus (Hoot et al., 2010). Thus, chronic nerve injury appears to result in region specific alterations in the function of multiple G-protein-coupled receptor types, and together, these changes might contribute to the establishment and maintenance of chronic pain states.

Narita et. al. (2008) also performed opioid-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding on several brain regions including the thalamus and PAG following CCI, but found no significant differences between the sham and nerve ligated groups. Both the Narita study and ours used gross tissue dissections and differences in specific sub-regions included in each dissection could account for the discrepancy in the results. Also, Narita et al examined agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding at 7 days post nerve injury versus the 10 day post CCI time point examined in the current study. As demonstrated in the time course studies of DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the thalamus, reduced μ-opioid-stimulated G-protein activity was detected after 10 days of CCI, but not the earlier time points of 1 or 3 days post CCI. Thus, significant decreases in μ-opioid-mediated G-protein activity could require more than 7 days to develop.

A potential mechanism to explain the decrease in opioid-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the thalamus of CCI mice could be an increase in endogenous opioid release following nerve injury that causes desensitization of thalamic μ-opioid receptors. The observation that the reduction in G-protein activation in CCI mice was observed only at day 10 post-surgery and not earlier time points supports this hypothesis because tonic pain has been reported to increase levels of β-endorphin in several brain areas including the thalamus (Porro et al., 1988; Porro et al., 1991). Elevated levels of endomorphin, another putative endogenous ligand for the μ-opioid receptor, were also observed in the rat brain following CCI surgery (Sun et al., 2001).

Increased levels of endogenous opioid peptides could produce receptor desensitization by inducing G-protein-coupled receptor kinase -mediated phosphorylation and subsequent β-arrestin binding as previously described (Liu and Anand, 2001). A number of opioid agonists, including β-endorphin, induce μ-opioid receptor internalization and desensitization as demonstrated in cells that heterologously express the μ-receptor (Beyer et al., 2004). In vivo studies have shown that partial sciatic nerve ligation increases the levels of phosphorylated μ-opioid receptors in striatum as assessed using a phosphorylation-specific antibody (Petraschka et al., 2007). This effect is absent in β-endorphin knockout mice, providing further support for a role of endogenous β-endorphin release in μ-opioid receptor adaptation. In contrast, μ-opioid receptor phosphorylation in proenkephalin or prodynorphin knockout mice did not differ from wild-type controls, showing that this effect is specific to β-endorphin. Further evidence that β-endorphin release produces μ-opioid receptor desensitization is that sciatic nerve ligation induced a decrease in DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the VTA of wild-type mice but not in β-endorphin knockout mice (Niikura et al., 2008). The potential significance of this finding is evident from human PET studies that demonstrated reduced opioid receptor binding in several brain areas, including the thalamus, in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain conditions (Jones et al., 2004; Maarrawi et al., 2007; Willoch et al., 2004). This could reflect an increased level of endogenous peptide at the receptor and/or a change in receptor binding properties.

GPCR internalization can lead to receptor downregulation, which is a potential mechanism to explain the reduced receptor-mediated G-protein activity shown in the thalamus. However, [3H]naloxone binding did not differ between CCI and sham operated mice. Although naloxone is not specific for mu opioid receptors, it has approximately 3- and 79-fold higher affinity for mu versus kappa and delta opioid receptors, respectively (Emmerson et al., 1994) supporting the conclusion that mu opioid receptors were not downregulated in this model. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that μ-opioid receptor desensitization occurs in the absence of receptor down-regulation in the brainstem of morphine or heroin treated rats (Sim et al., 1996).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that CCI resulted in a decrease in μ-opioid receptor mediated G-protein activation in the thalamus and PAG of mice, which was significant at ten days post surgery. Although the effect in PAG was modest and could not be definitely attributed to a change in agonist potency or maximal effect, in thalamus there was a significant decrease in maximal receptor activity. This effect was not due to an overall decrease in μ-opioid receptors suggesting that the chronic pain-like condition produced by CCI resulted in desensitization of thalamic μ-opioid receptors. These data are the first to show a decrease in opioid stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the thalamus in response to nerve injury, and are consistent with the idea that neuropathic pain is associated with dysregulation in pain processing resulting in part from neuroadaptation of specific receptor systems in the brain.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1 Animals

Male Swiss Webster mice (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 25–30g were housed six to a cage in animal care quarters on a 12 h light-dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. Protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Virginia Commonwealth University and comply with recommendations of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).

4.2 Chronic Constriction Injury (CCI) of the Sciatic Nerve

Mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isofluorane and the lower back and right thigh were shaved. The shaved area was then cleansed with 2% povidine-iodine solution and rinsed with 70% ethyl alcohol. A linear skin incision was made along the lateral surface of the biceps femoris and blunt forceps were inserted into the muscle belly to split the muscle fibers and expose the sciatic nerve. The tips of the forceps were passed gently under the sciatic nerve and lifted to pass two 5-0 chromic gut sutures under the nerve, 1 mm apart. The sutures were then tied loosely around the nerve and knotted twice to prevent slippage. The incision was cleansed and the skin was closed with 2–3 ligatures of 5-0 dermalon. The mice were then placed on a warmed surface and following recovery, were returned to their home cages and checked routinely for 72 hours. A separate control group of sham-operated mice underwent the same surgical procedure with the exception of the ligation of the sciatic nerve.

4.3 Behavioral Testing

Thermal hypersensitivity was assessed using a radiant heat source applied to the plantar surface of the ipsilateral hindpaw (Hargreaves et al., 1988). For two days prior to CCI surgery, mice were placed on the acrylic glass floor of the apparatus (Plantar Test, Ugo Basile, Comerio, Italy) and covered with an inverted clear plastic tube to prevent escape and limit movement. Mice were allowed to acclimate to the Plantar Test for approximately 20 min prior to testing. Paw withdrawal latency was measured on the day of surgery (baseline) and again at 1, 3, or 10 days post CCI or sham surgery in separate groups of mice. On a given test day, five measures of paw-withdrawal latency were conducted with at least 5 minutes between each test with the mean latency used for statistical purposes. Paw-withdrawal latencies were expressed as relative values to baseline latencies for each animal, and group means ± S.E.M. Behavioral data were analyzed via Student’s t-test with differences considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. CCI surgery successfully induced thermal hypersensitivity in more than 95% of mice tested at days 3 or 10 post-surgery. One CCI mouse at day 3 post-surgery that failed to demonstrate statistically significant withdrawal latency from baseline was excluded from in vitro analysis.

4.4 Brain Dissection

Mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation following in vivo testing. Brains were removed and immediately placed on a glass plate on ice for dissection. An initial cut was made approximately 2 mm from the rostral pole of the brain and tissue anterior to the cut was removed. A second cut was made approximately 1.5 mm posterior to the first cut to produce a coronal brain section that corresponded to approximately Bregma +2.5 to Bregma +1. The cingulate cortex was dissected from the dorsal medial region of the resulting coronal section using the corpus callosum on the posterior surface as a ventral landmark and a mouse brain atlas (Paxinos, 2001) as a guide. The resulting sample contained primarily Cg1 and Cg2, and likely included immediately adjacent portions of prelimbic and secondary motor cortices. Thalamus was collected from a section that extended from approximately Bregma −0.3 to Bregma −2.7 using the rostral extent of the stria medullaris as an anterior landmark and the superior colliculi as a posterior landmark. Cortical and hippocampal tissue was removed dorsal and lateral to the thalamus. Tissue ventral to the thalamus was removed by cutting at the midpoint of the section, dorsal to the third ventricle. The sample included medial and lateral nuclei throughout the rostral-caudal extent of the thalamus as well as habenula. The PAG was dissected from approximately Bregma −3 to Bregma −5. This section was collected using the superior and inferior colliculi as anterior and posterior landmarks, respectively. Cortex and hippocampus were discarded and then the colliculi were removed. Tissue ventral to the PAG was removed at the midpoint of the section. The sample included PAG throughout its rostral-caudal extent, as well as surrounding reticulum. All tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further processing.

4.5 DAMGO-Stimulated [35S]GTPγS Binding

Tissue was collected as described above and stored at −80°C until further processing. On the day of the assay, tissue was thawed and sonicated in 5 ml of assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.7). The homogenate was centrifuged at 50,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 3–5 ml of assay buffer and sonicated. Protein levels were determined by the Bradford assay (Bradford, 1976) using BSA as a standard. Membranes were then incubated with 4 mU/ml adenosine deaminase for 35 min at 30°C. Membranes (8–10 μg) were incubated in assay buffer containing 30 μM GDP, 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS, and varying concentrations of the μ-opioid specific agonist [d-Ala2,(N-Me)Phe4,Gly5-OH] enkephalin (DAMGO). Non-specific binding was assessed by the addition of 20 μM unlabeled GTPγS and basal binding was assessed by omitting agonist. Samples (in triplicate) were incubated for 2 hr at 30°C with gentle agitation. The incubation was terminated by rapid filtration under vacuum through Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters, followed by three washes with ice-cold 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2. Bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry at 95% efficiency for 35S after extraction of the filters in 4 ml Budget Solve scintillation fluid and a 45 min shake cycle.

4.6 Opioid Receptor Binding

Brain membranes were diluted with membrane buffer and prepared under the same conditions as described for the [35S]GTPγS binding assays. Saturation binding assays were performed by incubating 30 μg of membrane protein with 0.1–2 nM [3H] naloxone in the presence and absence of 1 mM unlabeled naloxone to determine nonspecific and specific binding, respectively. Assay tubes (in duplicate) were incubated for 1.5 hr at 30°C. Reactions were terminated by rapid filtration under vacuum through Whatman GF/B glass-fiber filters that had been soaked in Tris buffer, pH 7.4, followed by three washes with the Tris buffer. Bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry after extraction of the filters in 4 ml Budget Solve scintillation fluid and a 45 min shake cycle.

4.7 Data Analysis

For [35S]GTPγS binding, basal binding is defined as specific [35S]GTPγS binding in the absence of agonist. Net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding is defined as [35S]GTPγS binding in the presence of agonist minus basal binding. The percentage of stimulation is expressed as (net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding/basal) × 100%. Concentration-effect curves generated for each brain region and each day post-surgery were analyzed via two-way ANOVA with surgical treatment and agonist concentration as the two main factors Emax and EC50 values were calculated from nonlinear regression analysis by iterative fitting of the concentration-effect curves to the Langmuir equation [E = Emax/(EC50 + agonist concentration) × agonist concentration] using Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). For [3H]naloxone binding, Bmax and KD values were calculated by iterative fitting of the saturation curves to the Langmuir equation [B = Bmax/(KD + ligand concentration) × ligand concentration] using Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc.). Emax and EC50 and Bmax and KD values were then analyzed via Student’s t-test for statistical significance between CCI and sham mice.

Research Highlights.

We examined effects of CCI on μ-opioid receptors in supraspinal pain pathways.

CCI reduced DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in thalamus but not rACC or PAG.

Naloxone binding in thalamus showed no significant differences in Bmax values.

CCI induces region-specific desensitization of the μ-opioid receptor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH training grant T32DA07027 and NIH grants R01DA020836, K05DA000480 and R01DA10770.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beyer A, Koch T, Schroder H, Schulz S, Hollt V. Effect of the A118G polymorphism on binding affinity, potency and agonist-mediated endocytosis, desensitization, and resensitization of the human mu-opioid receptor. J Neurochem. 2004;89:553–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin EO, Yeliseeva ZV, Vasilenko GF, Meizerov EE, Chuvin BT, Durinyan RA. Cortical projections to the periaqueductal grey in the cat: a retrograde horseradish peroxidase study. Neurosci Lett. 1984;51:271–5. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90563-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr KD, Bak TH. Medial thalamic injection of opioid agonists: mu-agonist increases while kappa-agonist decreases stimulus thresholds for pain and reward. Brain Res. 1988;441:173–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Shyu BC. A fMRI study of brain activations during non-noxious and noxious electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve of rats. Brain Res. 2001;897:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Kaplan RF, Zuffante P, Moser DJ, Jenkins MA, Salloway S, Wilkinson H. Alteration of intention and self-initiated action associated with bilateral anterior cingulotomy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;11:444–53. doi: 10.1176/jnp.11.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Audette J, Baron R, Gourlay GK, Haanpaa ML, Kent JL, Krane EJ, Lebel AA, Levy RM, Mackey SC, Mayer J, Miaskowski C, Raja SN, Rice AS, Schmader KE, Stacey B, Stanos S, Treede RD, Turk DC, Walco GA, Wells CD. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. 85:S3–14. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerson PJ, Liu MR, Woods JH, Medzihradsky F. Binding affinity and selectivity of opioids at mu, delta and kappa receptors in monkey brain membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:1630–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz EL, White LE. The role of rostral cingulumotomy in “pain” relief. Int J Neurol. 1968;6:353–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte SE, Lagman AL, Borszcz GS. Antinociceptive effects of morphine injected into the nucleus parafascicularis thalami of the rat. Brain Res. 2000;874:78–86. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02583-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoot MR, Sim-Selley LJ, Poklis JL, Abdullah RA, Scoggins KL, Selley DE, Dewey WL. Chronic constriction injury reduces cannabinoid receptor 1 activity in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex of mice. Brain Res. 1339:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu MM, Kung JC, Shyu BC. Evoked responses of the anterior cingulate cortex to stimulation of the medial thalamus. Chin J Physiol. 2000;43:81–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RW, Ballantine HT., Jr Stereotactic anterior cingulate lesions for persistent pain: a report on 68 cases. Clin Neurosurg. 1974;21:334–51. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/21.cn_suppl_1.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanmonod D, Magnin M, Morel A. Chronic neurogenic pain and the medial thalamotomy. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 1994;83:702–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TS, Gottrup H, Sindrup SH, Bach FW. The clinical picture of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;429:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AK, Watabe H, Cunningham VJ, Jones T. Cerebral decreases in opioid receptor binding in patients with central neuropathic pain measured by [11C]diprenorphine binding and PET. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:479–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoromi S, Cui L, Nackers L, Max MB. Morphine, nortriptyline and their combination vs. placebo in patients with chronic lumbar root pain. Pain. 2007;130:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krout KE, Loewy AD. Periaqueductal gray matter projections to midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:111–41. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000814)424:1<111::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung JC, Shyu BC. Potentiation of local field potentials in the anterior cingulate cortex evoked by the stimulation of the medial thalamic nuclei in rats. Brain Res. 2002;953:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JG, Anand KJ. Protein kinases modulate the cellular adaptations associated with opioid tolerance and dependence. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;38:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maarrawi J, Peyron R, Mertens P, Costes N, Magnin M, Sindou M, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Differential brain opioid receptor availability in central and peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Kaneko C, Miyoshi K, Nagumo Y, Kuzumaki N, Nakajima M, Nanjo K, Matsuzawa K, Yamazaki M, Suzuki T. Chronic pain induces anxiety with concomitant changes in opioidergic function in the amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:739–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niikura K, Narita M, Nakamura A, Okutsu D, Ozeki A, Kurahashi K, Kobayashi Y, Suzuki M, Suzuki T. Direct evidence for the involvement of endogenous beta-endorphin in the suppression of the morphine-induced rewarding effect under a neuropathic pain-like state. Neurosci Lett. 2008;435:257–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki S, Narita M, Iino M, Miyoshi K, Suzuki T. Suppression of the morphine-induced rewarding effect and G-protein activation in the lower midbrain following nerve injury in the mouse: involvement of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Neuroscience. 2003;116:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Petraschka M, Li S, Gilbert TL, Westenbroek RE, Bruchas MR, Schreiber S, Lowe J, Low MJ, Pintar JE, Chavkin C. The absence of endogenous beta-endorphin selectively blocks phosphorylation and desensitization of mu opioid receptors following partial sciatic nerve ligation. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porro CA, Facchinetti F, Pozzo P, Benassi C, Biral GP, Genazzani AR. Tonic pain time-dependently affects beta-endorphin-like immunoreactivity in the ventral periaqueductal gray matter of the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1988;86:89–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porro CA, Tassinari G, Facchinetti F, Panerai AE, Carli G. Central beta-endorphin system involvement in the reaction to acute tonic pain. Exp Brain Res. 1991;83:549–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00229833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saade NE, Al Amin H, Abdel Baki S, Chalouhi S, Jabbur SJ, Atweh SF. Reversible attenuation of neuropathic-like manifestations in rats by lesions or local blocks of the intralaminar or the medial thalamic nuclei. Exp Neurol. 2007;204:205–19. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim LJ, Selley DE, Dworkin SI, Childers SR. Effects of chronic morphine administration on mu opioid receptor-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS autoradiography in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2684–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02684.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun RQ, Wang Y, Zhao CS, Chang JK, Han JS. Changes in brain content of nociceptin/orphanin FQ and endomorphin 2 in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2001;311:13–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuor UI, Malisza K, Foniok T, Papadimitropoulos R, Jarmasz M, Somorjai R, Kozlowski P. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in rats subjected to intense electrical and noxious chemical stimulation of the forepaw. Pain. 2000;87:315–24. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu S, Konigsmark B, Walker AE. Thalamotomy for alleviation of intractable pain. Confin Neurol. 1974;36:88–96. doi: 10.1159/000102786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JY, Huang J, Chang JY, Woodward DJ, Luo F. Morphine modulation of pain processing in medial and lateral pain pathways. Mol Pain. 2009;5:60. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoch F, Schindler F, Wester HJ, Empl M, Straube A, Schwaiger M, Conrad B, Tolle TR. Central poststroke pain and reduced opioid receptor binding within pain processing circuitries: a [11C]diprenorphine PET study. Pain. 2004;108:213–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung JC, Yaksh TL, Rudy TA. Concurrent mapping of brain sites for sensitivity to the direct application of morphine and focal electrical stimulation in the production of antinociception in the rat. Pain. 1977;4:23–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung JC, Yaksh TL, Rudy TA. Effect on the nociceptive threshold and EEG activity in the rat of morphine injected into the medial thalamus and the periaqueductal gray. Neuropharmacology. 1978;17:525–32. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(78)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RF, Jacques DS, Rand RW, Copcutt BC, Vermeulen SS, Posewitz AE. Technique of stereotactic medial thalamotomy with the Leksell Gamma Knife for treatment of chronic pain. Neurol Res. 1995;17:59–65. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1995.11740287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]