Abstract

We investigate knowledge of core syntactic and semantic principles in individuals with Williams Syndrome (WS). Our study focuses on the logico-syntactic properties of negation and disjunction (or) and tests knowledge of (a) core syntactic relations (scope and c-command), (b) core semantic relations (entailment relations and DeMorgan’s laws of propositional logic), and (c) the relationship between (a) and (b). We examine the performance of individuals with WS, children matched for mental age (MA), and typical adult native speakers of English. Performance on all conditions suggests that knowledge of (a-c) is present and engaged in all three groups. Results also indicate slightly depressed performance on (c) for the WS group, compared to MA, consistent with limitation in processing resources. Implications of these results for competing accounts of language development in WS, as well as for the relevance of WS to the study of cognitive architecture and development are discussed.

1. INTRODUCTION

This article is concerned with the linguistic abilities of individuals with Williams Syndrome (WS). Over the past 20 years, WS has received considerable attention from scholars interested in the structure and development of the human mind. The main reason is that this rare genetic disorder represents a natural experiment, which suggests a potential dissociation between language and other aspects of cognition. To be sure, WS is often described as being characterized by relatively spared linguistic abilities in the face of serious deficits in other cognitive domains such as space and number (Bellugi et al., 1988; Bellugi et al., 1994; Bihrle et al., 1989; Karmiloff-Smith, 1992, 1997; Udwin et al., 1987; Mervis et al., 1999; Ansari, Donlan, & Karmiloff-Smith, in press).

WS is thus often cited as evidence supporting the kind of modular view of mental architecture advocated most famously by Jerry Fodor (1983) and Noam Chomsky (1965, 1986, 1995) (Anderson, 1998; Bikerton, 1997; Piatelli-Palmarini, 2001; Pinker 1994). Recent developments, however, have led to a somewhat more nuanced picture of the linguistic profile of individuals with WS and, more importantly, to the emergence of two strongly conflicting views regarding the nature of linguistic abilities in this population.

On the one hand, proponents of modularity have argued that what is spared in WS is not language as a whole, as earlier accounts may have suggested, but rather the computational system contained within the language faculty (i.e., the set of rules used to form words, phrases, and sentences)1 (e.g., Clahsen & Almazan, 1998; Pinker, 1999). On the other hand, recognition of such a potential within-domain dissociation, in conjunction with results from a small set of recent studies (e.g., Karmiloff-Smith et al., 1997; Volterra et al., 1996; Capirci et al., 1996), have led some to the opposite conclusion, namely that grammar and morphosyntac-tic rules are in fact impaired or deviant in WS. These conclusions have been interpreted from the perspective of a new framework, called the ‘neuroconstructivist approach’, which represents an alternative to modularity (e.g., Karmiloff-Smith, 1998; Thomas & Karmiloff-Smith, 2002, 2005; Mareschal et al., 2007).

To further complicate the picture, recent accounts of WS, based on extensive reviews of the literature, interpret the facts about language abilities in this disordered population as neither compatible with modularity (broadly or narrowly construed) nor with neuroconstruc-tivism (Brock, 2007; Thomas, in press). This conclusion stems from the observation that language abilities in WS neither exceed what one would expect on the basis of mental age —hence no dissociation between language and general cognitive abilities, contra modularity — nor reflect atypical or deviant underlying knowledge — as would be predicted by neuroconstruc-tivism. This general observation is captured by what Karmiloff Smith and Thomas (2003) call the ‘conservative hypothesis’ (also see Brock, 2007; Thomas, in press), according to which language development proceeds normally in WS but is delayed, due to the effects of mental retardation.

It is plain to see that these conflicting conclusions have significant implications for theories of the structure and development of the human mind (see Zukowski, 2001; Brock, 2007, for detailed discussion). Thus, the incompatibility of some of the views described above regarding the nature and development of linguistic abilities in WS calls for a broader investigation of grammar in this disordered population. A larger data set, in turn, will provide the kind of empirical wedge that one would need to begin teasing apart these competing accounts. Accordingly, we propose here to broaden the empirical basis upon which competing accounts of the linguistic abilities of individuals with WS can be evaluated.

In order to do so, we focus on the logico-syntactic properties of expressions such as negation and disjunction (i.e., or) and test knowledge of (a) core syntactic relations (scope and c-command), (b) core semantic relations (entailment relations and DeMorgan’s laws of propositional logic), and (c) the relationship between (a) and (b). We selected these phenomena because they involve knowledge of core properties of the computational system of language and thus directly bear on the predictions of the two views under investigation.

Our principal question is whether individuals with WS interpret sentences in ways that require that they engage the core properties of the computational system described above. The crux of the issue here is whether language in WS is “spared” in the sense that individuals with WS know these core properties of language.2 If not, does any impairment reflect abnormalities in the core linguistic subsystems and structures within each? The relevant data are the absolute level of performance of people with WS, with the assumption that one simply cannot interpret the key sentences appropriately without engaging these properties.

A secondary question is how the performance of individuals with WS compares to neurologically normal individuals, including adult native speakers of English (who will provide a measure of ceiling), children matched to the WS group for mental age, and children who are younger than mental age matches. To the extent that differences in absolute levels of performance emerge between individuals with WS and neurologically normal individuals, we can then ask whether performance relative to other control groups reflects different representations, or, alternatively, limitations in the processes that are used to carry out the computations required to understand and produce the relevant sentences.

To preview, our results demonstrate that knowledge of (a–c) is present in and engaged by individuals with WS, as it is by adults and typically developing children. We conclude that far from being ‘superficial’ — to use Karmiloff and Karmiloff-Smith’s (2001) description — grammatical knowledge in WS is governed by the same abstract principles that characterize typically developing and mature systems.

2. WILLIAMS SYNDROME: BASIC FACTS, THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES AND IMPLICATIONS

Williams Syndrome is a rare genetic disorder with a prevalence of about 1 in 7,500 live births (Strømme et al., 2002), which is due to a micro-deletion of genetic material on chromosome 7 (Ewart et al., 1993). Individuals with WS present with both physical and cognitive abnormalities. Physical abnormalities include cardiac anomalies and unusual facial features, and cognition is characterized by an uneven profile with areas of relative strength, such as language, alongside severe weaknesses in domains such as space, number, planning, and problem solving (e.g., Bellugi et al., 1988; Karmiloff-Smith et al., 1997). Even in the area of spatial representation and number, however, there are distinct strengths and a considerable degree of spared structure (Landau & Hoffman, 2007). The results on spatial representation in individuals with WS provide an important perspective: Although there are clear deficits in performance level relative even to mental age matched children, many core aspects of spatial representation are preserved, suggesting that careful study might reveal the same for language. As mentioned earlier, competing perspectives have emerged regarding the linguistic abilities of individuals with WS. These different views can be seen as falling on a spectrum with the two main theoretical contenders, modularity and neuroconstructivism, on either end, and the more recent ‘conservative hypothesis’ somewhat in the middle. In the discussion below, we consider the main features of each of these perspectives.

2.1 The Modular Approach

The classic Chomskyan/Fodorian view maintains that the mind contains a domain-specific set of principles dedicated to the acquisition of language — a language ‘module’ or language ‘organ’ to use famous metaphors. In his seminal discussion of modularity, Fodor (1983) proposed that mental modules meet nine criteria, namely domain specificity, obligatory firing, inaccessibility to consciousness, speed, encapsulation, shallow outputs, localization, ontogenetic invariance, and characteristic breakdown patterns. It is important to point out, however, that Fodor did not intend for these criteria to be necessary properties of modules. Rather, to quote Fodor himself, “one would thus expect — what anyhow seems desirable — that the notion of modularity ought to admit of degrees … [w]hen I speak of a cognitive system as modular, I shall therefore always mean “to some interesting extent” (p. 37). Thus, it has been argued that Fodor’s treatment of modularity suggests that he took it as a natural property, rather than something to be diagnosed through a checklist (see Sperber, 1994, for a discussion of this idea).

Moving beyond Fodor, subsequent theorizing has led many evolutionary psychologists to view modularity through the lens of functional specialization, a concept borrowed from biology (Pinker, 1997, 2005; Sperber, 1994, 2005; Tooby & Cosmides, 1992). To be sure, it has long been known to biologists that structure often reflects function. To use one of Pinker’s (1997) analogies, “[i]t would be silly to try to understand why chairs have a stable horizontal surface by cutting them open and putting bits of them under a microscope. The explanation is that someone designed the chair to hold up a human behind” (p. 314). Pinker (1997) goes on to tells us that he “ … think[s] of the ways of knowing in anatomical terms, as mental systems, organs, and tissues, like the immune system, blood, or skin. They accomplish specialized functions, thanks to their specialized structures …[our emphasis]” (p. 315). Thus, according to Pinker (1997), modules ought to be defined in terms of the operations they perform on the information that is relevant to them, rather than through an invariant set of necessary features (for a detailed discussion of these ideas and their implications for the notion of modularity, see Barrett & Kurzban, 2006).

Another important notion, held by most theoretical linguists, is that the language module itself has a modular structure and that it minimally contains two submodules, namely a lexicon — a list of stored entries specifying category membership for abstract entities such as nouns, verbs, and prepositions, along with other idiosyncratic information — and a computational system — a set of rule-like operations that combine lexical entries to construct larger structures such as words, phrases, and sentences (Chomsky, 1995). Given this view of language, proponents of modularity have argued that WS has a differential impact on the lexicon and computational system by affecting the former while sparing the latter (Clahsen & Almazan, 1998; Clahsen & Temple, 2003; Pinker, 1999). To quote Clahsen and Temple (2003): “They [Clahsen & Almazan, 1998] argued that these two core modules of language are dissociated in WS such that the computational (rule-based) system for language is selectively spared, while lexical representations and/or their access procedures are impaired” (p. 2).

2.2 The Neuroconstructivist Approach

Within the past decade, an alternative to the modular view has emerged, mainly under the impetus of work by Elman, Bates, Johnson, Karmiloff-Smith, Parisi, and Plunkett (2001). These new ideas have been applied to neurodevelopmental abnormalities under a framework known as neuro-constructivism (Karmiloff, 1998; Karmiloff-Smith, 1997, 1998; Karmiloff & Karmiloff-Smith, 2001; Thomas & Karmiloff-Smith, 2005; Westermann et al., 2007; Thomas, in press). One of the paradigm cases for this approach is WS. At the heart of the neuroconstructivist view lie two important, related claims, namely (a) that individuals with WS learn language using cognitive mechanisms that are different from the ones used by typically developing children and (b) that knowledge of grammar and morphosyntax is compromised in WS3.

The following quotes illustrate these two claims: “In sum … Williams Syndrome also displays an abnormal cognitive phenotype in which, even where behavioral scores are equivalent to those of normal controls, the cognitive processes by which such proficiency is achieved are different (Karmiloff-Smith, 1998, p. 395). “The results of the two present studies … challenge the often cited claim that the particular interest of Williams Syndrome for cognitive science lies in the fact that morphosyntactic rules are intact [our emphasis] (Karmiloff-Smith et al., 1997, p. 257), and finally, “The final semantic and conceptual representations [our emphasis] formed in individuals with WS appear to be shallower, with less abstract information and more perceptually based detail …” (Thomas & Karmiloff-Smith, 2003, p. 652).

Thus, neuroconstructivism explicitly rejects modularity (specifically, the notion that the computational system of language is intact), on both empirical and theoretical grounds. To quote Karmiloff-Smith (1998), “this change in perspective means that atypical development should not be considered in terms of a catalogue of impaired and intact functions, in which non-affected modules are considered to develop normally, independently of the others. Such claims are based on the static, adult neuropsychological model which is inappropriate for understanding the dynamics of developmental disorders” (p. 390).

Another related claim is that language abilities in WS appear to be impressive, at least on the surface because individuals with WS have good auditory memory skills. Karmiloff and Karmiloff-Smith (2001) said that “it has become increasingly clear, therefore, that the superficially impressive language skills of individuals with WS may be due to good auditory memory rather than an intact grammar module” (pp. 202–203). Moreover, this approach emphasizes the role of rote learning in WS along with the relative inability of this population to extract underlying regularities and form linguistic generalizations. The following two quotes from Karmiloff-Smith et al. (1997) illustrate these points. “This suggests that if WS children go about language acquisition differently from normal children … they will end up — as they indeed do — with large vocabularies but relatively poor system building” (p. 257). “We challenge these claims [about modularity] and hypothesize that the mechanisms by which people with WS learn language do not follow the normal path. We argue that the language of WS people, although good given their level of mental retardation, will not turn out to be “intact” (p. 247).

Finally, some of the empirical evidence offered in support of the neuroconstructivist view comes from a study by Karmiloff-Smith et al. (1997) reporting that English-speaking individuals with WS experience difficulty with the interpretation of embedded clauses and that French-speaking individuals with WS have trouble with certain aspects of grammatical gender. Unusual syntactic and morphological errors have also been reported by Volterra et al. (1996) as well as Capirci et al. (1996) who studied Italian-speaking individuals with WS.

2.3. The Conservative Hypothesis

In more recent work, Thomas and Karmiloff-Smith (2003) consider, based on a review of the literature, two types of hypothesis regarding potential sources of atypicality in WS language. The first is what they call the conservative hypothesis “in which it is argued that the language we see in WS is merely the product of delayed development combined with low IQ” (p. 652). As an alternative to the conservative hypothesis, these authors propose the semantics-phonology imbalance theory which claims that language development in WS takes place under altered constraints. The specific idea here is that individuals with WS have a particular strength in auditory short-term memory accompanied by a relative weakness in lexical semantics. A major consequence of this imbalance is that individuals with WS rely more on phonological information than semantic information when processing language, which may lead to certain behavioral impairments.

In his review of language abilities in WS, Brock (2007) observes that there is little evidence that the ‘end state’ of language development is atypical in WS and, therefore, that there is no empirical support for Thomas and Karmiloff-Smith’s semantics-phonology imbalance hypothesis. Instead, Brock concludes that, by and large, the available evidence is consistent with the ‘conservative hypothesis’. This conclusion is echoed by Thomas (in press) who acknowledges, citing Brock’s (2007) study, that as research on WS progressed, the ‘conservative hypothesis’ has gained more support over the ‘imbalance hypothesis’. Thus, Thomas’s explicit goal is to find a compromise between modularity and neuroconstructivism. Finally, it is worth pointing out that Tager-Flusberg, Plesa-Skwerer, Faja, and Joseph (2003) arrive at essentially the same conclusion, as illustrated by the following quote from these authors: “Despite claims to the contrary (Karmiloff-Smith et al., 2002), there is no evidence that children with WMS acquire language any differently than other children, although they may be delayed in the onset of first words and phrases, as would be expected given their mental retardation (Morris & Mervis, 1999)” (p. 20).

3. THEORETICAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL BACKGROUND

This section lays out the theoretical concepts and vocabulary that we will later be using to test WS people’s knowledge of grammar. Studying the development of grammar, in typical or atypical populations, requires some familiarity with the framework used to study grammar in the first place, linguistic theory. Here we use sentences containing negation and disjunction (or) to uncover knowledge of much more abstract syntactic and semantic principles. Thus, our first task is to show what these abstract principles are and how they enter into explanation of the facts under investigation. Specifically, we introduce the syntactic notions of scope and c-command and the semantic notions of entailment relations and DeMorgan’s laws of propositional logic. We also explain how these two sets of principles relate to each other. In a nutshell, we show that negation can interact with disjunction, or, to give rise to a pattern of entailment relations known as DeMorgan’s laws of propositional logic. Whether or not the interpretation of negation and disjunction is subject to DeMorgan’s laws, in turn, depends on the kind of syntactic relation holding between these two elements. Specifically, for DeMorgan’s law to hold, or must occur in the scope (i.e., c-command domain) of negation. We then show that these principles, in addition to explaining what mature speakers know about English, have also been used to explain what younger, typically developing children know about their growing language.

Consider the sentences in (1–2).

-

(1)

All of my students passed their exam.

-

(2)

Some of my students passed their exam.

Notice that whenever (1) is true, (2) is also necessarily true. In other words, if it is the case that all of my students passed their exam, then it follows that some of my students passed their exam. Consequently, we say that (1) entails (2), but not vice versa (the fact that some of my students passed their exam does not necessarily mean that all of them did). More generally, we can say that propositions containing all entail equivalent propositions containing some, but not vice-versa, as shown in (3).

-

(3)

All A are B ⇒ Some A are B

Next, consider the examples in (4–5).

-

(4)

John bought a car.

John bought a red car.

-

(5)

John didn’t buy a car.

John didn’t buy a red car.

Notice that (4a) does not entail (4b). In other words, if John bought a car, he did not necessarily buy a red one. Interestingly, however, when the sentences in (4) are negated, as in (5), (5a) now entails (5b). Indeed, if it is true that John did not buy a car, then it must also be true that he did not buy a red car. Notice further that the kind of entailment relations created by the presence of negation has a directionality. That is, negation licenses inferences from sets (the sets of cars) to subsets (the set of red cars). Thus, negation is called a downward entailing expression, that is, one that licenses inferences from sets to subsets. In contrast, the verb phrase (VP) of a declarative sentence creates an upward entailing context, namely a context in which inferences from subsets to sets are licensed. To be sure, (4b) entails (4a), but not vice versa: if it is true that John bought a red car, it is obviously also true that John bought a car. Here we have an inference from the set of red cars (the subset) to the sets of cars (the superset).

Scholars interested in natural language semantics have noticed that downward entailing expressions, such as negation, display an interesting set of properties. One such property concerns the interpretation of the disjunction operator, or. First, notice that in a declarative sentence such as (6), or typically receives a disjunctive interpretation. That is, the most natural interpretation of (6) is that John bought one kind of car or the other, but not both4. Another way to say this is that (6) does not entail (7). In other words, if John only bought a BMW, (6) would be true, but (7) would not.

-

(6)

John bought a BMW or a Mercedes.

-

(7)

John bought a BMW and John bought a Mercedes.

Consider now what happens when (6) is turned into a negative, as in (8).

-

(8)

John didn’t buy a BMW or a Mercedes.

-

(9)

John didn’t buy a BMW and John didn’t buy a Mercedes.

In the presence of negation, or is now interpreted conjunctively. That is, (8) is interpreted as meaning that John bought neither a BMW nor a Mercedes. Unlike in the case of (6) and (7), (8) now entails (9). This interpretive pattern, relating statements containing disjunction to statements containing conjunction is captured by one of De Morgan’s famous laws of propositional logic, as shown in (10). Following standard logical notation, ¬ is the symbol for negation, ∨ the one for the disjunctive operator, or, and ∧ the one for the conjunctive operator, and. In plain English, (10) states that the negation of the disjunction of two propositions is logically equivalent to the conjunction of their negations.

-

(10)

¬(P ∨ Q) ⇔ (¬ P) ∧ (¬ Q)

In light of the previous discussion, the examples in (11) and (12) would at first sight appear to be problematic. To be sure, both examples contain negation and the disjunctive operator, or, and yet, only (12) seems to obey De Morgan’s law. In other words, (12a) entails (12b), but (11a) does not entail (11b). Put another way, we get a disjunctive reading of or in (11a) and a conjunctive reading in (12a). Why should this be?

-

(11)

The man who didn’t get a pay raise bought a BMW or a Mercedes.

The man who didn’t get a pay raise bought a BMW AND the man who didn’t get a pay raise bought a Mercedes.

-

(12)

The man who got a pay raise didn’t buy a BMW or a Mercedes.

The man who got a pay raise didn’t buy a BMW AND the man who got a pay raise didn’t buy a Mercedes.

The short answer is that negation’s powers are only potent in certain syntactic configurations. The detailed answer requires the introduction of three important and independently motivated theoretical notions: the notion of syntactic structure, the notion of scope, and the notion of c-command.

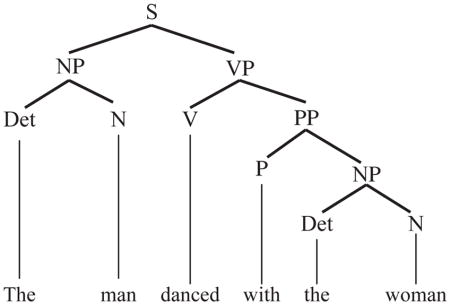

One of the central and most famous conclusions of Chomsky’s (1957) foundational work in syntax is that linguistic representations are hierarchical and that the rules of grammar make reference to this hierarchal organization. Thus, a sentence like (13) is not just a string of words but rather can be represented as being hierarchically organized, as shown in (14a–b) which are notational variants of one another.

-

(13)

The man danced with the woman.

-

(14)

[S [NP The man] [VP danced [PP with [NP the woman]]]]

In addition, syntacticians have noticed that a broad range of seemingly disparate linguistic phenomena can receive a principled explanation if one assumes the notion of c-command, a structural relation defined over hierarchical structure. C-command, in turn, is defined as follows.

-

(15)

x c-command y iff

x ≠y

Neither x dominates y nor y dominate x

The first branching node that dominates x also dominates y

A useful rule of thumb to calculate c-command without using the formal definition in (15) is to start with the element whose c-command domain one wants to calculate, go up in the tree structure to the first branching node, and then go down. Everything on the way down from the branching node is contained within the c-command domain of the element in question. Thus, in our example in (13), the NP the man c-commands the VP, the PP and the NP the woman.

Hierarchical structure and c-command, in turn, each play a crucial role in the notion of scope. Scope can be illustrated using a simple mathematical analogy. Consider the mathematical expressions 2 x (3+5) and (2 × 3) + 5. The scope of 2 x (the number 2 followed by the multiplication sign) can be thought of as its domain of application. Thus, in 2 x (3+5), (3 + 5) falls within the scope of 2x. In contrast, in (2 × 3) + 5, 3 falls within the scope of 2x whereas 5 falls outside of its scope. Notice finally that different scope relations give rise to different results once the expressions are computed. We can now consider the notion of scope as it applies to language. Certain expressions, such as negation, for example, are scope-bearing expressions. Scope, in turn, is defined in terms of the notion of c-command, as given in (16).

-

(16)

Scope principle: an expression α takes scope over an expression β iff α c-commands β.

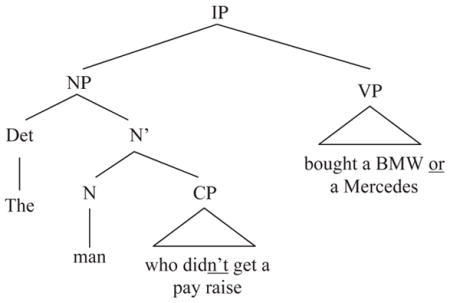

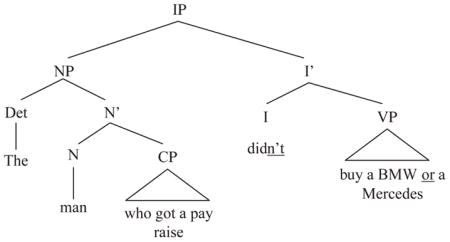

Retuning to the interpretation of or with respect to negation, we can now say that or receives a conjunctive interpretation — in other words, that De Morgan’s law holds — if or falls within the scope of negation; that is, if it falls within the c-command of negation. We can now return to the examples in (11) and (12), repeated here as (17), and see that negation, which is too deeply embedded within the subject NP does not c-command or in (17a) but that it does c-command or in (17b). This explains why only (17b) obeys DeMorgan’s law. The reader can verify that for himself/herself by looking at the tree diagrams provided in (18a) and (18b) and applying the rule of thumb (or the formal definition) given for c-command. Readers unfamiliar with X-bar terminology need not worry about the labels. What matters here is the structure of those sentences and the fact that negation either c-commands or fails to c-command or.

-

(17)

[IP [NP The man who didn’t get a pay raise] [I’ [VP bought a BMW or a Mercedes]]]

[IP [NP The man who got a pay raise] [I’ didn’t [VP buy a BMW or a Mercedes]]]

-

(18)

To recap, negation, a downward-entailing operator, can interact with disjunction, or, to give rise to a pattern of entailment relations known as DeMorgan’s laws of propositional logic. Whether or not the interpretation of negation and disjunction is subject to DeMorgan’s laws, in turn, depends on the kind of syntactic relation holding between these two elements. Specifically, for DeMorgan’s law to hold, or must occur in the scope, that is, the c-command domain, of negation.

Another important property of the theoretical notions described above is that in addition to explaining what mature speakers know about English (and other languages as well, of course), these principles have also been shown to explain what young children know about English and thus why the course of language development does not vary arbitrarily. There is a large literature on this topic, spanning several decades, including a number of introductory books, for example, Crain and Thornton (1998), Crain and Lillo-Martin (1999), and Guasti (2001). In addition, many experimental studies have uncovered knowledge of the very principles discussed above in young children. For syntactic structure, see, for example, Lidz et al. (2003), Crain (1991), Crain and Nakayama (1985), and Lidz and Musolino (2002), among many others. For knowledge of c-command in young children, see Crain (1991), Lidz and Musolino (2002), and Crain et al. (2002). For entailment relations, see Noveck (2001), Papafragou and Musolino (2003), and Musolino and Lidz (2006). Finally, for knowledge of DeMorgan’s laws in preschoolers, see Gualmini and Crain (2002), Crain et al. (2007), Crain et al. (2002), and Minai, Goro, and Crain (2006).

To illustrate these conclusions with a concrete example, consider the study by Lidz and Musolino (2002). These authors asked how adult and child speakers of English interpret scopally ambiguous sentences such as The Smurf didn’t catch two birds. Notice that on one reading this sentence can be paraphrased as meaning that it is not the case that the Smurf caught two birds —maybe she caught only one. Here, the phrase two birds is interpreted within the scope of negation. Alternatively, one could interpret that sentence as meaning that there are two specific birds that the Smurf did not catch. In this case, the phrase two birds would be interpreted outside the scope of negation. What Lidz and Musolino (2002) showed is that typically developing 4 year olds differ from adults in that they display a strong preference for the reading in which two birds is interpreted within the scope of negation. In order to determine whether children’s behavior was constrained by the linear order of negation and two birds or by the c-command relations holding between these elements, Lidz and Musolino tested 4-year-old (and adult) speakers of Kannada, a Dravidian language in which, because of differences in word order, linear order and c-command relations are not confounded, as they are in English in this case. What Lidz and Musolino (2002) found is that 4 year olds are constrained by the c-command relations holding between the quantificational elements, not their linear order. This shows that abstract and independently motivated notions such as c-command can be used to explain developmental patterns.

4. EXPERIMENT

In the following experiment, we propose to assess (a) semantic knowledge of the basic truth conditions associated with negation and disjunction (or) as well as core semantic notions such as entailment relations and DeMorgan’s laws of propositional logic; (b) knowledge of core syntactic notions, namely scope and c-command; and (c) the relationship between (a) and (b). In order to test knowledge of (a–c), we have chosen an experimental technique that has proved to be very successful in assessing (typically developing) children’s interpretation of a broad range of complex linguistic constructions, often involving ambiguous sentences and intricate interactions between logical expressions, including some of the notions and principles under investigation in the present study (Musolino, Crain, & Thornton, 2000; Lidz & Musolino, 2002; Musolino & Lidz, 2003; Musolino & Lidz, 2006). This technique is called the Truth Value Judgment Task (TVJT) (Crain & Thornton, 1998).

It is worth pointing out that there is now solid evidence that children as young as 4 experience no difficulty with the TVJT and that they are capable of giving either Yes or No answers when appropriate, including appropriate justifications for their answers. Moreover, the TVJT has now been used successfully to test young children’s knowledge of complex linguistic constructions in different languages, including English (Musolino, 2004), Greek (Papafragou & Musolino, 2003), Kannada (Dravidian) (Lidz & Musolino, 2002), and Korean (Han, Lidz, & Musolino, 2007). Finally, the TVJT has recently been used to uncover complex grammatical knowledge in WS (Zukowski, 2001). In our experiments, we will show that knowledge of the facts in (a–c) can be assessed by asking participants to judge sentences containing the various expressions under investigation in a range of configurations corresponding to the different interpretations that such sentences produce.

4.1. Participants

Participants included four groups of 12 individuals: a group of individuals with WS (6 males and 6 females) (mean age = 16;4 (year, month), SD = 11.07 months, age range = 11;10–21.11), a group of typically developing children matched to the WS group on the basis of mental age (MA) (6 boys and 6 girls) (mean age = 6;1, SD = 3.3 months, age range = 5;2–7;8), a group of typically developing 4 year olds (5 boys and 7 girls) (mean age = 4;3, SD = 3.7 months, age range = 4;0–4;11), and a group of 12 typical adult speakers of English (7 females and 5 males).

The WS individuals all received a positive diagnosis using a FISH (fluoride in situ hybridization) test (Ewart et al., 1993). WS and MA individuals were matched using raw scores on the nonverbal subtest of the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (KBIT; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990). This test is a standardized IQ test that has relatively few spatial items and hence does not unfairly penalize people with WS for their severe spatial deficit. Mean raw scores for the non-verbal subtest of the KBIT were 21.66 (SD = 1.22) for people with WS and 20.5 (SD = 1.39) for the MA matched children. Mean raw scores on the verbal subtest were 41.4 (SD = 1.88) for the WS group and 33.75 (SD = 1.03) for the MA controls. The higher verbal scores for the WS group was expected, as vocabulary level in people with WS typically increases beyond overall nonverbal mental age by adolescence5.

The WS IQ profile was typical with a mean IQ of 62.75 (SD = 4.19) on the KBIT, (compared to mean = 118.5, SD = 2.44 for the MA group). In addition, the profile was typical in showing severe spatial impairment, reflected in scores below the 3rd percentile for age on a standardized block assembly task (Differential Abilities Score; Elliot, 1990). Individuals with WS were recruited through the Williams Syndrome Association, and MA controls through local preschools in the Baltimore, Maryland, area. Typically developing 4-year-olds were recruited at preschools in the Baltimore area and in the Bloomington, Indiana, area. Finally, the adults were all undergraduate students at Indiana University.

4.2. Design, Materials, and Procedure

Participants watched short computer-animated vignettes and heard recorded spoken sentences that described the vignettes. They then made judgments of the truth value of each sentence (“right” or “wrong”) in the context of the vignette. Interpretation of sentences varied depending on the syntactic structure and inclusion of negation and the disjunction operator, or.

The design included two experimental and four control conditions, which isolated the components of the experimental conditions. In the two experimental conditions, participants were tested on their interpretation of sentences such as (19) and (20). Both sentences involve a subject NP which contains a relative clause, both contain negation and both contain the disjunction operator, or. The crucial difference between (19) and (20) is whether or occurs in the scope, i.e. in the c-command domain of negation (see section 2). In examples such as (19), negation both precedes and c-commands or, whereas in examples such as (20) negation precedes but does not c-command or. Thus, sentences such as (19) and (20) were used to determine whether participants have knowledge of the way that negation and disjunction interact in syntactic contexts where negation either merely precedes, or both precedes and c-commands or. In both examples, we held constant the number of words intervening between negation and or, namely four.

-

(19)

The cat who meows will not be given a fish or milk.

-

(20)

The owl that does not hoot will get bugs or a mouse.

Notice now that the difference in c-command relations between negation and or in the examples above gives rise to opposite truth conditions for sentences such as (19) and (20). Truth conditions are simply the set of circumstances under which a sentence is true or false (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sample Truth Conditions for Precede and C-Command Statements

| If given a fish or milk | If given something else | |

|---|---|---|

| C-Command | False | True |

| The cat who meows will not be given a fish or milk | ||

| Precede | True | False |

| The cat who does not meow will be given a fish or milk |

The four control conditions isolated each of the elements that interacted in the experimental sentences. Specifically, being able to correctly calculate the truth conditions of sentences such as (19) and (20) also involves understanding (a) the meaning of or, (b) the meaning of negation, (c) knowing about De Morgan’s laws, and (d) being able to parse a relative clause. Thus, our four control conditions were designed to independently test for knowledge of (a–d).

Participants were therefore tested in a total of six conditions (two experimental conditions, namely ‘precede’ and ‘c-command’, and four control conditions, namely ‘or’, ‘negation’, ‘De Morgan’ and ‘relative clause’. See Appendices 1 and 2 for a complete list of statements).

APPENDIX 1.

EXPERIMENTAL CONDITIONS12

| Vignette | C-command Statements | Outcome | True/False |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two tow-trucks, a motorcycle, a car, and a boat. | The tow-truck that beeps its horn will not pick up a car or a motorcycle. | The relevant tow-truck picked up the boat. | True |

| Two cats, a fish, milk, and a mouse. | The cat who meows will not be given a fish or milk. | The relevant cat gets the mouse. | True |

| Two policemen, a cup of coffee, doughnuts, and a newspaper. | The policeman who is blowing his whistle will not be given a newspaper or doughnuts. | The relevant policeman gets the cup of coffee. | True |

| Two girls, a racket, a towel, and water. | The girl who is playing tennis will not be given a towel or water. | The relevant girl gets the racket. | True |

| Two ducks, a fish, bread, and grapes. | The duck who quacks will not be given the fish or the bread. | The relevant duck gets the fish. | False |

| Two clowns, a jewel, a coin, and some dollar bills. | The clown who is holding a flower will not be given a jewel or a coin. | The relevant clown gets the coin. | False |

| Two boys, pop corn, a candy-bar, and soda. | The boy with the money will not be given the candy-bar or the popcorn. | The relevant boy gets the popcorn. | False |

| Two kids, a ball, suntan lotion, and an umbrella. | The kid who is building a castle will not be given a ball or an umbrella. | The relevant kid gets the umbrella. | False |

|

| |||

| Vignette | Precede Statements | Outcome | True/False |

|

| |||

| Two owls, bugs, a bird, and a mouse. | The owl that does not hoot will get bugs or a mouse. | The relevant owl gets the mouse. | True |

| Two monkeys, a football, bananas, and an apple. | The monkey who is not asleep will get bananas or a ball. | The relevant monkey got the bananas. | True |

| Two snowmen, skates, a sled, and skis. | The snowman who does not wave will get skates or a sled. | The relevant snowman got the sled. | True |

| Two boys, candy, ice-cream, and a coin. | The boy who is not running will get candy or ice-cream. | The relevant boy gets the candy. | True |

| Two cowboys, boots, a saddle, and a hat. | The cowboy who is not riding will get boots or a hat. | The relevant cowboy gets the saddle. | False |

| Two pirates, a map, gold, and a jewel. | The pirate who is not sitting will get gold or a map. | The relevant pirate gets the jewel. | False |

| Two dogs, bones, French fries, and a steak. | The dog who does not bark will get bones or French fries. | The relevant dog got the steak. | False |

| Two bees, honey, flowers, and a hive. | The bee that does not buzz will get flowers or honey. | The relevant bee got the hive. | False |

APPENDIX 2.

CONTROL CONDITIONS13

| Control Conditions | True/False |

|---|---|

| Negative Statements | |

| The boy did not get a bicycle. | True |

| The butterfly did not land on the flowers. | True |

| The tired monkey did not get a banana. | True |

| The jeans did not get washed. | True |

| The green frog could not jump on the rock. | False |

| The little girl is not making cookies. | False |

| The penguin did not catch the fish. | False |

| The little girl will not get the watering can. | False |

| Disjunction statements | |

| The policeman will get a cup of coffee or the doughnuts. | True |

| The boy will get a banana or French fries. | True |

| The toolbox will get a hammer or a screw-driver. | True |

| This dinner comes with water or a soda | True |

| The girl will get a cat or a dog. | False |

| The hippo will get soap or shampoo. | False |

| The boy will get the beach ball or the sun tan lotion. | False |

| The tickets are for the airplane or the movie theatre. | False |

| Relative Statements | |

| The man who has a red tie is walking a dog. | True |

| The car that beeps its horn will get the new tires. | True |

| The fireman who has a hose has the dog. | True |

| The apple that is on top of the book has a worm in it. | True |

| The rabbit who has on blue pants is playing guitar. | False |

| The clown who is on a bike is holding a yellow flower. | False |

| The little girl who has blond hair has two dolls. | False |

| The rooster who is on the fence will crow. | False |

| DeMorgan Statements | |

| The baseball player will not get the glove or the hat. | True |

| The bunny will not get lettuce or tomatoes. | True |

| The bee did not land on the white or the yellow flower. | True |

| The bear will not get ketchup or broccoli. | True |

| The man will not get the brush or the razor. | False |

| The kid will not get playing cards or a yoyo. | False |

| The elephant will not get peanuts or cheese. | False |

| The shopping cart will bet get oranges or watermelon. | False |

In each of the six conditions, participants were asked to judge the truth of eight different statements; for example, eight statements in which negation only precedes or, eight statements in which negation precedes and c-commands or, and so forth. Of these eight statements, four were true and four were false. This was achieved by creating true and false outcomes for each vignette/ sentence combination (see Appendices for details). The six conditions by eight statements yielded a total of 48 statements to be judged, 24 true and 24 false.

Four lists of 48 statements were created in which the two sets of experimental statements (precede and c-command) were blocked and the control statements were randomly interspersed throughout the blocks. In two of the lists, the set of ‘c-command’ statements appeared first and in the other two, the set of ‘precede’ statements appeared first. Participants were randomly assigned to a list, but WS individuals were assigned to the same list as their MA control.

All vignettes were created and animated using Microsoft PowerPoint software and displayed on a computer monitor. A prerecorded female voice described each vignette as events unfolded, and at the end a statement describing the outcome of each vignette was made (see Appendix 1 for sample context). The participants were told they would watch the vignette and hear a voice saying something, and their task was to determine whether the voice was ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. The task was identical for participants in all four groups. Adult participants were told that the task was designed for use with young children and mentally retarded individuals and that their responses would be used to generate a baseline for performance in these other groups.

4.3. Results

In the analyses below, our dependent measure is the percentages of correct responses. Table 2 summarizes the data and provides the percentages of correct responses for each of the four groups in all six conditions (standard deviation given in parentheses). In addition, we provide, for each group, the mean percentages of correct responses collapsed over the two experimental and the four control conditions.

TABLE 2.

Percentages of Correct Responses

| Experimental Conditions

|

Control Conditions

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precede | C-command | Mean Exp. | Neg | Relative | Or | De Morgan | Mean Control | |

| Adults | 97.9% (7.2) | 100% | 99.4% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| WS | 77% (15.8) | 75% (22.6) | 76% | 86.4% (16.3) | 96.8% (7.7) | 93.6% (11.5) | 86.4% (14.5) | 90.8% |

| MA Matches | 87.5% (13) | 91.6% (18.7) | 89.5% | 93.7% (11.3) | 95.8% (8.1) | 94.7% (8.3) | 93.7% (15.5) | 94.5% |

| 4-year-olds | 60.4% (20.5) | 64.5% (19.8) | 62% | 84.3% (17.7) | 90.6% (12) | 80.2% (18.8) | 82.2% (16.4) | 84% |

Note: Standard deviation is given in parentheses.

Adult participants performed at (or close to) ceiling on both experimental and control conditions, showing that our method is capable of tapping linguistic knowledge in this domain. We do not consider their data further.

Recall that our principal question is whether individuals with WS interpret sentences containing or and negation in ways that require that they engage core properties of the computational system of language (e.g., scope, c-command). Thus, the relevant data here are the absolute levels of performance of individuals with WS, with the assumption that one simply cannot interpret the key sentences appropriately at levels above chance without engaging these properties6. Accordingly, we compared performance levels on both the experimental and control conditions against chance performance (i.e., 50% acceptance rate). For each experimental and control condition, we found that individuals with WS performed significantly above what would be expected by chance (all ps < .01).

Next, we turn to our secondary question, namely how the performance of individuals with WS compares to that of neurologically normal individuals. In order to address this question, we analyzed the proportions of correct responses using a 3 (group: WS, MA, 4-year-olds) by 2 (conditions: experimental vs. control) mixed design ANOVA. The analysis revealed a main effect of group (F(2, 33) = 9.05, p< 0.01), a main effect of condition (F(1,33) = 50, p < 0.001), and a significant interaction between group and condition (F(2,33) = 6.28, p < 0.01).

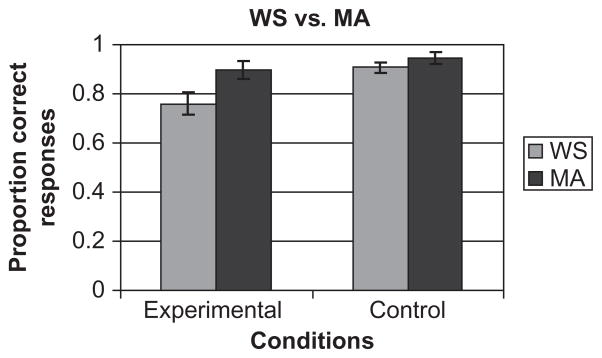

To compare the performance of our group of WS individuals to that of children matched for MA, we began by considering the performance of our MA group against chance levels. We found that this group, like the group with WS, performed significantly above chance on each experimental and control condition (all p < .001). We then compared WS and MA using a 2(group: WS vs. MA) by 2(conditions: experimental vs. control) mixed design ANOVA. The analysis revealed a main effect of group (F(1, 22) = 4.12, p = 0.05), a main effect of condition (F(1,22) = 23.07, p < 0.001), and a significant interaction between group and condition (F(1,22) = 5.66, p < 0.05). Thus, overall, the MA group performed better than the WS group, the control conditions yielded a higher proportion of correct responses compared to the experimental conditions, and the difference in performance between WS and MA was larger in the experimental conditions than in the control conditions.

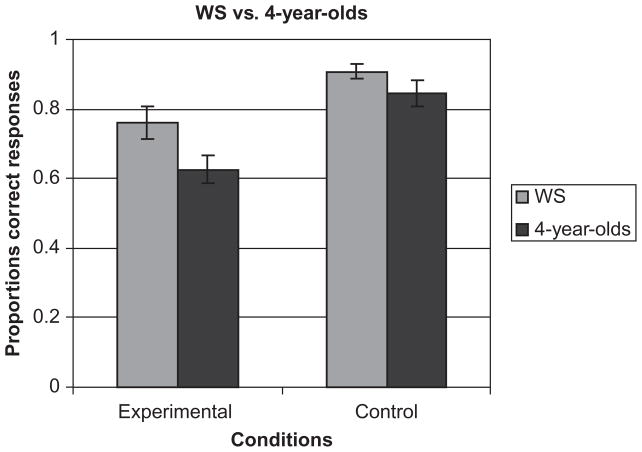

To further analyze these effects, we ran separate ANOVAs to compare WS and MA on the two sets of conditions, namely, experimental and control. For control conditions, a 2 (group: WS vs. MA) by 4 (condition: negation, or, De Morgan and relative clause) mixed design ANOVA was performed on the proportions of correct responses. The analysis revealed no significant main effect of group (F(1, 22) = 1.40, p = 0.24), no significant main effect of condition (F(3, 66) = 1.99, p = 0.12) and no significant interaction between group and condition (F(3, 66) = 0.91, p = 0.43). To compare performance on the experimental conditions, a 2 (group: WS vs. MA) by 2 (condition: precede vs. c-command) mixed design ANOVA was performed on the proportions of correct responses. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of group (F(1, 22) = 5.32, p < 0.05), no significant effect of condition (F(1, 22) = 0.057, p = 0.81) and no significant interaction between group and condition (F(1, 22) = 0.51, p = 0.48). In other words, there were no reliable differences between the WS individuals and MA matches on any of the control conditions, but there was overall poorer performance on the experimental condition among people with WS (see Graph 1).

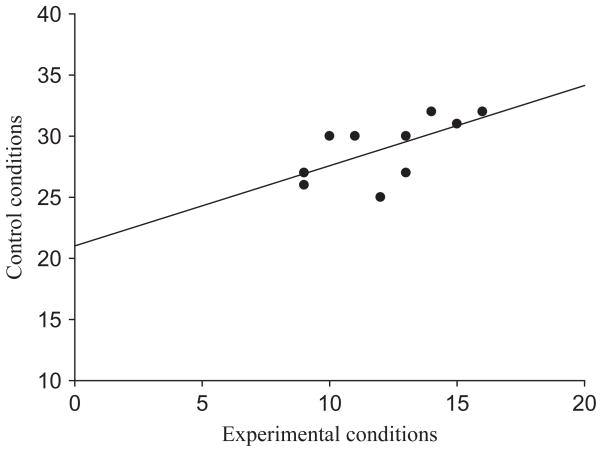

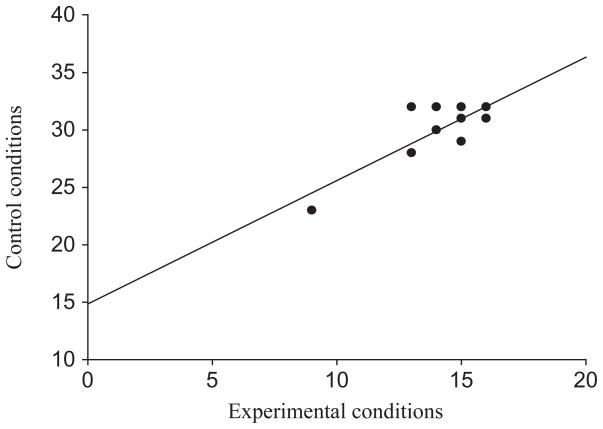

To refine our comparison between WS and MA, we asked, in separate analyses, the extent to which performance on the control conditions, for each individual in these two groups, would predict performance on the experimental conditions. Since performance on the experimental conditions is in part a function of what participants know about each of the separate components tested in the control conditions, we thought that this analysis might point to particular pockets of weakness in the control conditions that might predict overall performance in the experimental conditions. In order to do this, we computed, for each individual in both groups, an experimental score (an average of performance over the two experimental conditions) and a control score (an average of performance on the four control conditions). We then tested for correlations between the two scores. We found significant correlations between these two scores for both groups, r = 0.68, p = 0.014 for WS, and r = 0.82, p = 0.001 for MA. Thus, for each group, the level of difficulty experienced in the control conditions is significantly related to the level of difficulty experienced in the experimental conditions (see Graphs 2 and 3).

Given this finding, one possible explanation for the fact that WS and MA differ only in the experimental conditions, is that the compounding effect of having to interpret sentences which contain negation, disjunction and a relativized subject — as opposed to having to interpret these components one at a time in the control conditions — leads to more processing difficulties for WS than for MA. To further investigate this question, we used a multiple regression analysis (stepwise) to assess the contribution of each of the control variables to overall performance in the experimental conditions. Recall that the components interacting in the experimental conditions are negation, disjunction and a subject containing a relative clause. Accordingly, the control conditions were designed to assess performance on each of these components independently, so we have four control conditions: negation, disjunction, relative clause, and DeMorgan. The fourth control condition, DeMorgan, was included to check participant’s knowledge of DeMorgan’s laws in simpler sentences which do not contain a relative clause. Thus, DeMorgan is really a combination of ‘negation’ and ‘disjunction’. The idea here is to determine the relative importance of each of these interacting components to overall performance on the experimental conditions.

For people with WS, the regression model kept the variables ‘negation’ and ‘DeMorgan’ as significant predictors (p = 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively), with negation by itself accounting for 46% of the variance and negation combined with DeMorgan accounting for 66% of the variance. The other two variables, disjunction and relative clause, were rejected by the model. The fact that the model kept negation as a significant predictor of overall difficulty makes very good sense as it is well known in the psycholinguistic literature on sentence processing that negatives are typically associated with processing difficulty (see Horn, 1972, and references cited therein). For the MA-matched children, the model also kept negation as a significant predictor (p < 0.001) accounting for 63.7% of the variance and it rejected disjunction and relative clauses. However, the model for MA also rejected DeMorgan. What is interesting to observe here though is that for the MA children the variables ‘negation’ and ‘DeMorgan’ were highly correlated, r = 0.73, p < 0.01 which suggests that these two variables account for redundant portions of the variance and probably explains why the model didn’t keep them both. For the WS group, however, ‘negation’ and ‘DeMorgan’ are uncorrelated, r = 0.11, p = 0.36. This difference suggests that while negation is associated with processing difficulty for both WS and MA individuals, the interaction between negation and disjunction (i.e., DeMorgan) is associated with a different level of difficulty in the two groups. One way to interpret this result would be to speculate that whereas negation by itself gives rise to approximately the same level of processing difficulty for both WS and MA matched individuals, the combination of negation and disjunction is more difficult to process for people with WS compared to their MA matches.

In sum, for both MA matched children and people with WS, performance on the control conditions is significantly related to performance on the experimental conditions. Moreover, in both cases, negation is a significant predictor of overall performance. Finally, the interaction between negation and disjunction seems to create more processing difficulty for people with WS than for the MA matched group. Put another way, people with WS can handle processing complexity — and therefore look like their MA matches — up to a certain critical threshold or ‘tipping point’ which, once crossed, leads the system into a crash — albeit a rather minor one in this case (recall that on average, people with WS responded correctly 76% of the time in the experimental conditions compared to 89.5% for the MA matched children).

If this is correct, we are predicting that individuals with less efficient processing skills, such as younger typically developing children for example (i.e., children younger than 6), should, like individuals with WS, experience more difficulty with the experimental conditions than the control conditions. In other words, we predict that typically developing 4-year-olds might show the same consequences of complexity as people with WS. Let us first examine the performance of our group of 4-year-olds on the experimental and control conditions. Beginning with the latter, we found that 4-year-olds performed significantly above chance on all four control conditions (all p < .001). This shows that younger children did not experience difficulty with the task and that they have knowledge of the meaning of the components interacting in the experimental conditions. On the experimental conditions, we found that 4-year-olds performed significantly above chance on ‘c-command’ (t(11) = 2.54, p < .05), but that performance on ‘precede’ was not significantly different from chance performance (t(11) = 1.75, p = .10)7. We also found that performance on the control conditions was uncorrelated with performance on the experimental conditions. This lack of correlation is most likely because 4-year-olds are at chance on one of the experimental conditions.

Turning now to our prediction, we performed a 2 (group: WS vs. 4-year-olds) by 2 (condition: experimental vs. control) mixed design ANOVA on the proportions of correct responses. As expected, the analysis failed to reveal an interaction between group and condition (F(1,22) = 1.74, p = 0.2), but it revealed a significant main effect of condition (F(1,22) = 44.85, p < 0.001), and a significant main effect of group (F(1,22) = 4.81, p < 0.05). The main effect of condition reflected the difficulty of the experimental conditions relative to the control conditions; the main effect of group reflected better performance among people with WS than typically developing 4-year-olds (see Graph 4).

Recall that the same analysis comparing WS and MA groups revealed a main effect of group and a main effect of condition as well, but that it also revealed a significant interaction between group and condition, which is not found between WS and typically developing 4-year-olds. Thus, this pattern reveals the relative difficulty of the experimental conditions compared to the control conditions for both our WS and 4-year-old groups.

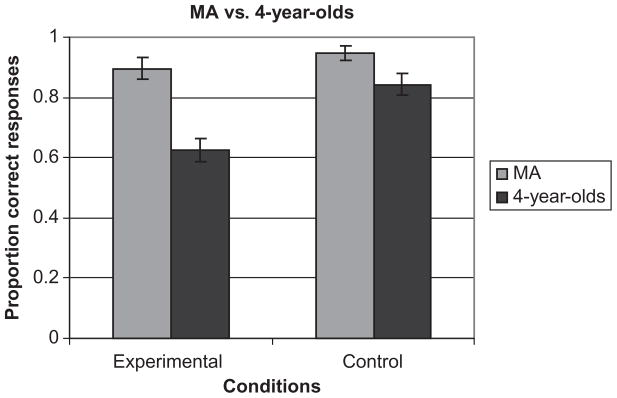

To the extent that the difference in performance between WS individuals and 4-year-olds on the one hand, and MA matches on the other, reflects the greater complexity of the experimental conditions compared to the control conditions, we may be able to observe this effect when comparing our two groups of typically developing children, namely MA matches and 4-year-olds. Put another way, we may expect that 4-year-olds would behave disproportionately worse than MA matches (i.e., 6-year-olds) on the experimental conditions compared to the control conditions. That is, we would expect here, as in the case of WS versus MA, to uncover an interaction between group and condition. To find out, we ran a 2 (group: MA vs. 4-year-olds) by 2(conditions: experimental vs. control) mixed design ANOVA. In addition to a significant main effect of group (F(1,22) = 18.46, p<0.001) and condition (F(1,22) = 32.1, p<0.001) reflecting the fact that overall, MA performed better than 4-year-olds, and that overall performance on the control conditions was higher than on the experimental conditions, the analysis also revealed a significant interaction between group and condition (F(1,22) = 12.78, p<0.01) (see Graph 5).

To recap, we uncovered a group by condition interaction when comparing the performance of WS and MA. That is, while WS and MA performance was on a par on the control conditions, WS performance was significantly below that of MA on the experimental conditions. Subsequent analyses suggest that this difference reflects the greater complexity of the experimental conditions compared to the control conditions coupled with the assumption that individuals with WS have more limited processing resources compared to MA controls. If so, we should be able to observe a developmental trend whereby younger participants ought to be more sensitive to the relative difficulty of the experimental conditions compared to the control conditions. This is indeed what we uncovered in subsequent analyses comparing individuals with WS with typically developing 4-year-olds, and 4-years-olds with MA (6-year-olds). Here we found that the group by condition interaction uncovered in the WS versus MA comparison was no longer present when WS was compared to a younger group, that is, 4-year-olds, but that the developmental effect reappeared when 4-year-olds were compared to MA.

4.4. Discussion

The first important observation emerging from our results is the flawless performance of our adult participants. In addition to establishing the relevant benchmark against which to compare the performance of our three other groups (i.e. WS, MA, and 4-year-olds), this fact shows that the intuitions of linguists regarding the intricate syntactic and semantic behavior of logical operators such as negation and disjunction can be verified experimentally. Second, the overall excellent performance of the WS and MA groups — with both groups performing well above chance on all conditions — clearly indicates that these participants did not experience any difficulty with the task.

Let us now consider the implications of WS and MA performance on the control conditions. Recall that these conditions were designed to assess knowledge of the individual components interacting in the experimental conditions, namely, knowledge of the basic set of truth conditions associated with negation, disjunction, as well as the logical laws regulating the interaction between the two (DeMorgan’s laws). Overall performance for both groups on the control conditions was excellent (90.8% correct on average for people with WS and 94.5% for MA-matched children) and no differences were found between the two groups. What this shows for people with WS is semantic knowledge of the basic truth conditions associated with negation, the disjunction operator, or, as well as knowledge of the logical laws regulating the interaction between the two.

The importance of this conclusion is worth stressing. In the case of or, near perfect performance (93.68% correct) shows that WS individuals have a firm grasp of the logical function of the disjunction operator. In other words, they know that statements such as John will get coffee or tea are true if John gets either coffee or tea and false if he gets neither. Another way to say this is that individuals with WS know that or can receive what we called a disjunctive interpretation. Excellent performance on the DeMorgan control (86.46% correct) shows that individuals with WS also have a firm grasp of what happens when the disjunction operator interacts with negation. Specifically, they know that a statement such as John didn’t have coffee or tea is true if John had neither but false if he had either tea or coffee. In other words, individuals with WS know that when or occurs in the scope of negation, it receives a conjunctive interpretation. As we shall now see by looking at what happened in the experimental conditions, individuals with WS also know that or receives a conjunctive interpretation only when it occurs in the c-command domain of negation, but not otherwise.

Turning to performance on the experimental conditions then, two interesting observations emerge. The first is that WS performance on these conditions was quite good (77.08 % correct for ‘precede’ and 75% correct for ‘c-command) and in both cases significantly above chance. This shows that individuals with WS know that the interaction between negation and disjunction gives rise to the pattern of entailment relations described by DeMorgan’s laws only when disjunction occurs in the c-command domain of negation. Put another way, individuals with WS know that the truth conditions associated with sentences containing negation and disjunction differ depending on whether disjunction falls within the c-command domain of negation (see Table 1). People with WS thus know about scope and c-command as well as their semantic consequences for the interpretation of negation and disjunction. The second noteworthy observation is that WS performance in the experimental conditions (but not the control conditions) is slightly lower than that of MA controls. We come back to this observation in the next section.

5. GENERAL DISCUSSION

We investigated knowledge of core syntactic and semantic principles in individuals with WS. Specifically, we have been concerned with (a) fundamental syntactic relations (scope and c-command) (b) fundamental semantic relations (entailment relations and DeMorgan’s laws of propositional logic), and (c) the relationship between (a) and (b). Our main question has been whether such grammatical structure is present in WS. Our results demonstrate that individuals with WS interpret sentences of English in ways that require the presence of the grammatical structure/principles in (a–c). Because these principles represent core aspects of the computational system of language, that is, rule-like operations governing the structure and interpretation of sentences, our results are compatible with approaches which predict such knowledge to be present and engaged in WS (i.e., modularity and the conservative hypothesis), but they raise a serious challenge to the neuroconstructivist view, which predicts qualitative differences in the system of knowledge underlying linguistic abilities in WS compared to typically developing individuals.

In the following discussion, we elaborate on these conclusions, framing the issues in a broader context, and addressing potential objections. First, we consider the nature of the challenge to neuroconstructivism posed by our results. This is done through a discussion of the notion of ‘selective sparing’, a key point of contention between the rival theories under consideration. To this end, we distinguish two versions of the neuroconstructivist thesis: a strong and a weak one. We then show that the strong thesis is empirically untenable, and that the weak one is at best orthogonal to the issue of modularity. Having shown that our results are incompatible with neuro-constructivism, we then consider their implications for modularity and the conservative hypothesis. Finally, we turn to our secondary question, namely how the performance of individuals with WS compares to that of neurologically normal individuals.

5.1. Neuroconstructivism and ‘Selective Sparing’

Recall from section 2 that one of the key points of contention between the modular and neuro-constructivist views hinges on whether grammar is ‘intact’ or ‘selectively spared’ in WS (see Zukowski, 2001, for relevant discussion). The first step toward a productive resolution of this question is to try to understand exactly what is meant by ‘selective sparing’.

Let us begin with a distinction that both parties to this debate routinely make, namely, the difference between, on the one hand, behavioral levels on a given task, and, on the other hand, the underlying cognitive abilities which enter into the relevant behavior. That this distinction is indeed made by both parties can be seen from the following quotes from Karmiloff-Smith (1998): “… even when normal behavioural levels are found in a developmental disorder in a given domain, they might be achieved by different cognitive processes [her emphasis]” (p. 391), and from Zukowski (2004), “[i]t is relatively easy to quantify performance on tests of language. A more difficult task is translating a pattern of performance into conclusions regarding the linguistic abilities/mechanisms that underlie that performance” (p. 1). Given this distinction, we can interpret the phrase ‘intact/spared language’ in two ways. We can either decide that ‘intact/spared’ applies to the pattern of behavior on a given task, or, alternatively, that it applies to the cognitive structures underlying such behavior. Our primary claim concerns the latter, in particular whether grammatical knowledge is intact or spared.

The next issue is to decide how to evaluate whether grammatical knowledge is spared or not. Typically in the study of WS (as well as other developmentally atypical populations), scientists compare the performance of the target group to some other control group. There are choices to make here, as we alluded to in our introduction. If we decide that the right control group is unimpaired individuals of the same chronological age, then this is perhaps setting the bar too high, since people with WS are usually moderately retarded. As a consequence, scientists often choose to compare individuals with WS to individuals who are matched on mental age, as we have done here. Indeed, this matching method is one of the most common ones in the study of language (and other cognitive capacities) in people with WS; hence a common way to interpret the question of ‘selective sparing’ involves the relationship between language ability and mental age. As Zukowski (2001: 4) explains “By selective sparing what is usually meant is that language performance is better than one would expect on the basis of overall mental age …”. But choice of such control groups as the basis for deciding whether grammatical knowledge is spared or not is a mixed bag: Karmiloff-Smith (1998:395) articulates the problem as follows: “To state that a person has fluent language but an IQ of 51 indeed appears theoretically surprising and could lead to the conclusion that syntax develops in isolation from the rest of the brain. But to state that the same person has fluent language and an MA [mental age] of 7 yrs changes the conclusion.” This conclusion is echoed by Brock (2006, p. 13) “… comparison with data from typically developing children indicate that their [i.e. WS] grammatical abilities are no better than one would predict on the basis of overall cognitive abilities …”

In sum, we can define ‘selective sparing’ in the following three ways:

Selective sparing

Grammar is selectively spared in WS if:

Grammatical knowledge is present and has the same structure as posited in the typical, mature system, or

Behavioral levels on language tasks are at least as good as those of the relevant comparison group, or

Behavioral levels on language tests exceed what one would expect on the basis of mental age8.

With the above distinctions in mind, we can now think of two versions of neuroconstructivism: a strong and a weak one. The strong version would hold that grammar isn’t ‘selectively spared’ in WS individuals because (a) is not true. The weak version would claim that grammar is not spared in WS because either (b) or (c) (or both) is/are false.

Let us begin with an examination of the strong version of neuroconstructivism. As currently formulated, neuroconstructivism indeed makes claims about the nature of grammatical knowledge in WS, both explicitly and implicitly. Indeed, based on what Karmiloff-Smith and colleagues write, this conclusion is difficult to escape: “The results of the two present studies … challenge the often-cited claim that the particular interest of Williams syndrome for cognitive science lies in the fact that morphosyntactic rules [our emphasis] are intact” (p. 257). Or, to take another example, this time from Thomas and Karmiloff-Smith (2003), “the final semantic and conceptual representations [our emphasis] formed in individuals with WS appear to be shallower, with less abstract information and more perceptually based detail …” (p. 652).

The problems with the strong version of neurconstructivism should now be obvious: first, it is empirically falsified, at least within the confines of the phenomena under investigation. To be sure, our central empirical conclusion that the grammar of WS individuals is governed by the same abstract principles that characterize typically developing and mature systems flies in the face of any claims that grammar is either not present or abnormally structured in WS. Moreover, the strong neuroconstructivist thesis is theoretically implausible. This weakness comes from the repeated contention that WS individuals go about the task of language acquisition using different cognitive mechanisms, or that they are unable to extract underlying regularities or form linguistic generalizations (see section 2.2. for specific quotes and also Clahsen & Almazan, 1998, for related discussion).

If so, it would be astonishing, to say the very least, that individuals with WS end up constructing grammatical systems which are as complex and abstract as those found in typically developing individuals. All the more so when one learns that these ‘different’ cognitive mechanisms are good auditory memory, or good rote learning abilities. Short of a precise demonstration of how one would converge on the abstract notion of say, c-command (see section 4), simply by virtue of possessing good hearing skills or a large memory, such claims are devoid of any explanatory force. If anything, the default expectation should be that if good hearing or a powerful memory is what individuals with WS rely on when learning language, the grammatical systems that they end up building should be massively different from those found in typically developing individuals.

Let us now turn to what we called the weak version, beginning with the idea that ‘intact/spared’ applies to behavioral levels, instead of grammatical knowledge (see (b) above). In our mind, this option is a nonstarter. To see why, suppose that we were to indeed decide that behavioral levels constitute the relevant criterion. If so, we would conclude that population X, compared to control population Y, has ‘impaired grammar/language’ to the extent that behavioral levels on some relevant language task are not as good in population X as they are in population Y. On this view, an anti-modularity argument would take the following form: individuals with WS often show behavioral levels on language tests that are not as good as those seen in mental age controls. Therefore language/grammar in WS is not intact/spared. Therefore, modularity must be wrong. The problem with such an argument is that what is under attack here is a straw version of modularity. To be sure, differences in behavioral levels are in fact perfectly compatible with modularity. This is because the modularity thesis, a child of the cognitive revolution and the computational theory of mind, is a claim about mental architecture and operations, and thus only indirectly a claim about the nature of behavior itself. Thus, from a mentalistic perspective, differences in levels of behavior are, in and of themselves, uninformative, because they leave open the crucial question of what caused such differences in the first place. To quote Zukowski (2004), “… poor performance can be caused by many things: deviant or missing knowledge, parsing difficulty, memory overload, etc.” (p. 1). In sum, we may decide to chose behavioral levels as the relevant criterion in defining what counts as ‘intact/impaired’ language, but by doing so, we would ensure that our claims have no substantive bearing on the question of modularity.

Finally, let us consider the idea that we should talk about ‘spared’ grammar only to the extent that performance on language tests exceeds what one would expect on the basis of overall mental age (option (c) above). As Zukowski (2001) points out, there are some serious problems with such an approach. The first is that trying to settle the issue in this fashion yields different answers depending on one’s choice of the mental age-matched comparison group. Indeed, if the MA-matched group is also mentally retarded (e.g., Down syndrome), then WS language does surpass what one would expect based on MA. On the other hand, when the control group is not mentally retarded (e.g., typically developing children), then language in individuals with WS typically does not exceed MA-based expectations. To further complicate matters, there is evidence suggesting that WS language does not exceed MA-based expectations in early childhood, but that it does so in late childhood and in adulthood (Jarrold, Baddeley, & Hewes, 1998).

As Zukowski (2001) points out, the remarkable fact about WS is how good their language is given their level of mental retardation. Indeed, nobody denies that WS displays, to use Karmiloff-Smith’s own phrase “a verbal advantage over nonverbal intelligence.” Crucially, such a language ‘advantage’ is simply not found in populations with similar levels of mental retardation (e.g., Down syndrome), as has been amply demonstrated (e.g., Fowler, Gelman, & Gleitman, 1994). It follows that one simply cannot predict language ability on the basis of overall intelligence or other nonlinguistic cognitive factors; a fact which, if anything, lends credence to the conclusion that language is independent from other aspects of cognition, and thus to some interesting degree modular.

In sum, we believe that (a) is the crucial question for cognitive scientists and certainly for debates over modularity, whereas (b) and (c) are simply red herrings. Moreover, we contend that the claims made by proponents of neuroconstructivism regarding WS as it pertains to the broader issue of modularity end up failing for the following reasons: First, the strong version is theoretically implausible, and empirically falsified by the results of our study (see Brock, 2007 for a similar conclusion). Second, the weak version is at best orthogonal to the issues at stake because it argues against a straw version of modularity.

Finally, it bears emphasizing that we are not rejecting neuroconstructivism en bloc. To be sure, as discussed in section 2.2, neuroconstructivism makes a number of claims and suggestions, some of which we certainly agree with (e.g., adopting a developmental perspective; ultimately looking for lower-level underlying causes in the case of developmental disorders) and others pertaining to broad, foundational questions that fall far beyond the scope of the present article (e.g., nativism, constructivism, connectionism). What we are taking issue with here, as already discussed, are the empirical and theoretical claims made by neuroconstructivism as it pertains to WS.

5.2. Possible Objections

In the discussion below, we consider potential objections that could be raised against the conclusion we draw from our results, as well as its implications for the neuroconstructivist approach. One possible objection would be to argue that the neuroconstructivist view does not make the kinds of predictions that we ascribe to it. However, such a position would be very hard to defend. Consequently, this objection can be easily dismissed. Specifically, recall that the neuroconstructivist view has been presented as an alternative to the modular view — or the “strict nativist” view to use Karmiloff-Smith’s 1998 phrasing — and that it contains explicit claims that (a) knowledge of grammar (syntax and morphosyntax) is compromised in WS and (b) that grammar is learned in different ways by WS compared to typically developing children. In this regard, it is instructive to consider the logic of the neuroconstructivist view more carefully.