Abstract

Purpose: To analyse web-based training in ophthalmology offered by German university eye hospitals.

Methods: In January 2010 the websites of all 36 German university hospitals were searched for information provided for visitors, students and doctors alike.

We evaluated the offer in terms of quantity and quality.

Results: All websites could be accessed at the time of the study.

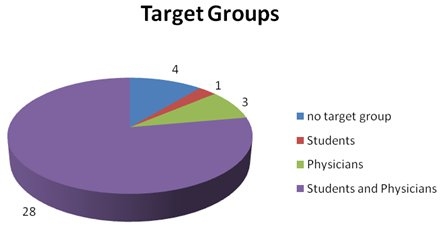

28 pages provided information for students and doctors, one page only for students, three exclusively for doctors. Four pages didn’t offer any information for these target groups. The websites offered information on events like congresses or students curricular education, there were also material for download for these events or for other purposes. We found complex e-learning-platforms on 9 pages. These dealt with special ophthalmological topics in a didactic arrangement. In spite of the extensive possibilities offered by the technology of Web 2.0, many conceivable tools were only rarely made available.

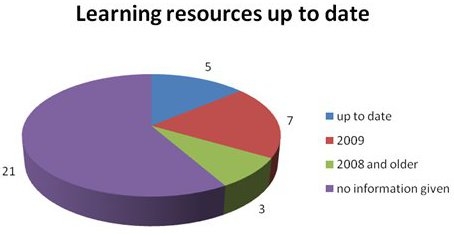

It was not always possible to determine if the information provided was up-to-date, very often the last actualization of the content was long ago. On one page the date for the last change was stated as 2004.

Conclusion: Currently there are 9 functional e-learning-applications offered by German university eye hospitals. Two additional hospitals present links to a project of the German Ophthalmological Society. There was a considerable variation in quantity and quality.

No website made use of crediting successful studying, e.g. with CME-points or OSCE-credits.

All German university eye hospitals present themselves in the World Wide Web. However, the lack of modern, technical as well as didactical state-of-the-art learning applications is alarming as it leaves an essential medium of today’s communication unused.

Keywords: Internet, world wide web, Web-based Training, WBT, e-Learning, Ophthalmology

Abstract

Zielsetzung: Analyse der webbasierten ophthalmologischen Lernprogramme, welche von den Internetseiten der Universitäts-Augenkliniken in Deutschland angeboten werden.

Methodik: Im Januar 2010 wurden in dieser prospektiven Studie alle 36 Internetseiten deutscher Universitäts-Augenkliniken besucht. Dabei wurde das angebotene Aus-, Weiter- und Fortbildungsangebot für Studierende und Ärzte quantitativ und qualitativ evaluiert.

Ergebnisse: Die Homepages aller Kliniken waren zum Zeitpunkt der Besuche erreichbar.

28 Internetseiten hielten Informationen zur Aus-, Weiter- oder Fortbildung für Studierende und Ärzte vor. Eine Seite beinhaltete nur Angebote für Studenten, 3 ausschließlich für Ärzte. Auf 4 Seiten wurde für beide Zielgruppen kein Angebot gemacht. Das Angebot umfasste Informationen zu aktuellen Veranstaltungen wie ärztlichen Fortbildungen oder Lehrveranstaltungen für Studierende, weiter wurden Skripte oder ähnliches Material zum download bereitgestellt. Auf 9 Seiten wurden komplexe e-learning-Plattformen aufgefunden, welche sich einem bestimmten Thema im Rahmen einer logisch-didaktischen Gliederung widmen. Trotz der umfangreichen Möglichkeiten, welches das Web 2.0 bietet, wurden viele denkbare Hilfsmittel nur selten bereitgestellt.

Die Aktualität des Angebots war nicht immer zu ermitteln, oft lag die letzte Aktualisierung lange zurück. Auf einer Seite war als letzte Aktualisierung der Fallsammlung das Jahr 2004 angegeben.

Schlussfolgerung: Von den Homepages der Augenabteilungen deutscher Universitätskliniken werden 9 funktionsfähige e-learning-Applikationen zur Verfügung gestellt. Zwei weitere Kliniken verweisen auf ein Projekt der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft.

Das Angebot zeigt eine erhebliche Variation in Quantität und Qualität. In keinem Fall wird die Möglichkeit der Anrechnung des Besuchs dieser Programme auf die studentische Ausbildung (z.B. OSCE-Credits) oder die ärztliche Weiter- oder Fortbildung, z.B. in Form von CME-Punkten, genutzt.

Der Mangel an modernen, technischen wie didaktischen Anforderungen genügenden Lernapplikationen ist alarmierend, wird doch ein wesentliches Kommunikations- und damit Lehr und Lernmedium von deutschen Universitäts-Augenkliniken nur zu einem kleinen Teil genutzt.

Introduction

Computer and Web-based Training in Ophthalmology

The potential for computer-based training in ophthalmology was already recognised in 1977 by Cuendet, Gygax et al. and their work already offered solutions to problems of implementation as the authors at the time thought that all technical barriers had been overcome (“Most of the technical obstacles have now been resolved.”) [5] Arden in 1985 described the changes manifest to and expected by him which would shape ophthalmology in the computer age. Education is explicitly counted amongst the areas which would benefit from computer support [3].

The first reports about the practical use of computer-assisted or computer-based teaching methods soon followed, usually dealing with single issues, with a comprehensive view of the subject seemingly not feasible at the time [9], [12], [15], [21], [22].

With the increasing potential of the available hard and software, bigger issues down to problem-based learning units are offered [6], [14], [16], [20], [18]. A comprehensive learning platform was presented by Schiefer et al. in Germany for the first time [27]. Some similar projects followed.

With the proliferation of the internet and the increasing number of users, this medium also moves into the focus of ophthalmology. Research on user behaviour, “ophthalmic web design”, etc was carried out [7], [8], [17]. [18].

Unsurprisingly, the mid-90s gave rise to an opposition movement which questioned various aspects of e-learning. Criticisms is levelled, amongst other things, at a lack of quality compared to commercial content offered on television or the internet, a lack of communication of human values and soft skills and a lack of integration into existing structures of medical education [4], [5], [10], [13]. These criticisms were valuable clues for improving the service content while technology was developing rapidly.

Live broadcasting over the internet became possible as the capacity for transmitting large amounts of data quickly improved [24], [23]. Large-scale educational software also began to become available online [31].

To counter the disadvantages of a lack of human interaction, a form of learning was developed which would come to be referred to as “blended learning”. This term subsumes all learning scenarios which are not exclusively face-to-face or take place exclusively online. This concept is based on the recognition that e-learning cannot replace traditional lectures but rather that these are supplemented by new media. It is therefore particularly important that presence phases and online phases are functionally coordinated with each other. The targeted use of the optimal mix at each step of the learning process, blended learning represents the most universal form of learning organization [32].

The term Web 2.0 was first mentioned in public in December 2003 in the US edition entitled “Fast Forward 2010 - The Fate of IT” in CIO Magazine, a specialist magazine for IT managers, in an article called “2004 - The Year of Web Services” by Eric Knorr. According to the article “What is Web 2.0” [http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html] by Tim O'Reilly dated 30 September 2005 the term was discussed internationally. Tim O'Reilly and Eric Knorr used a similar definition of the term Web 2.0. O'Reilly describes Web 2.0 as a change in business and a new movement in the computer industry towards using the internet as a platform. Specific technologies aside, the term Web 2.0 refers primarily to changes in the use and perception of the internet. Users create, edit and distribute content in a quantitatively and qualitatively critical way themselves, supported by interactive applications. Content is no longer solely created by commercial vendors and distributed via the internet but also by users networking using social networking software.

The internet seems a particularly appropriate forum for gaining or deepening knowledge in ophthalmology because of its multimedia capabilities, in particular the ability to represent images. Ophthalmology as a subject lends itself to computer-and web-based teaching as patient findings are often made on a visual basis. Examination techniques, such as auscultation and palpation in particular, are difficult to simulate but only play a minor role in ophthalmology [19]. All eye clinics in German university hospitals by now have a web presence to varying degrees.

The aim of this study is the quantitative and qualitative evaluation of e-learning offered at German university eye clinics in 2010. A list of clinics can be found here: http://www.thieme.de/viamedici/fach/augenheilkunde/kliniken.html

Materials and Methods

In January 2010, all web pages of German university eye clinics (n=36) were visited. The information offered on these pages regarding under- and postgraduate education and education offers was evaluated quantitatively and qualitatively.

The following points were checked:

Offers for students, physicians or both target groups

-

Information on teaching events

Currency, last update

Download of lecture scripts etc.

-

Information on current events in medical under- and postgraduate education

Currency

Scripts etc available for download.

-

e-learning

Data on target group

Peer review

Thumbnails

Leaflets etc.

Sorting

Video

Didactic structure

Nature of exams

Use of multimedia

Last update

A standard home computer (Intel Core Duo) was used. Netscape Explorer was used as a browser and the operating system was Windows XP. The connection to the internet was made using a high-speed access.

Results

Page Status

36 websites were visited, 35 of which were directly accessible, one site would not open with repeated attempts on the same day, another attempt two weeks later however gave access to the full website of the clinic.

Target Group

Almost all (28/36) websites contained information regarding under- or postgraduate education and CPD for students and physicians. One site only contained offers for students, 3 exclusively for physicians. 4 sites listed no offers for either target group. Only two sites allowed selecting the difficulty level prior to using the programme (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)).

Figure 1.

Nature and Content of Offers

The information regarding under- or postgraduate education and CPD which was found consisted of information on lectures, the course or exam dates, PhD position tenders, dates for medical CPD, downloadable scripts or PowerPoint™ slides for lectures, courses or training, link collections, online Quizzes down to complex, specially designed educational software.

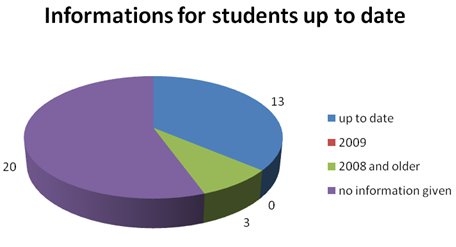

Information on courses for students was found on 27 of 36 sites. Only in 13 cases the information were up to date for the current semester, some pages were so general they applied to any semester, in a number of cases the information had not been updated for several semesters, down to the publication of a final exam from 8 semesters ago. Professional supplementary material for students, for example scripts or PowerPoint™ slides for download were only online in 8 cases.

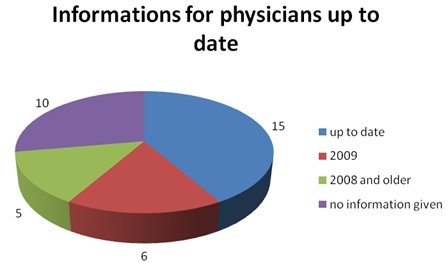

For medical visitors on the site, four sites offered additional specialist material. Organizational information, especially announcements of events were offered on 24 sites. CPD dates have been updated to 15 sites and sites which had not been updated in some cases dated back up to two years (see Figure 2 (Fig. 2), 3 (Fig. 3) and 4 (Fig. 4)).

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

The quantity of materials supplied also varied a lot. One image database offered almost 700 photographs; other providers had only a few photographs or cases.

Two hospitals refer to a project by the German Ophthalmological Society, which was created for students and doctors in post-graduate training as ophthalmologists. This page was not evaluated.

E-Learning

Content which goes beyond current information regarding teaching events, i.e. actual e-learning - was offered on nine sites with 13 applications. Nine of these are accessible to anyone, four are password-protected and accessible only to the target group, five applications, however, are no longer available, with the link leading to an error message on four and on one to a password prompt. In this last case, the webmaster was asked for the password and had to be made aware of the offer as he didn’t know about the programme himself at all.

12 sites also offered material for download, mostly lecture and seminar content.

The e-learning offer on the visited sites includes a collection of questions with visual diagnoses, a picture archive with 696 cases, a collection of 100 multiple-choice questions, imaging software and four comprehensive specialist learning platforms. The five unavailable programs could not be evaluated in terms of their content.

Basics, such as optics, anatomy, biochemistry or physiology were only covered by 2 learning software packages.

Treatment of diseases was only occasionally mentioned. Only one of the most popular applications contained a section specifically regarding conservative or surgical treatments.

Content was mostly ordered according to diseases or organ systems of the eye.

The learning progress is checked only rarely. In four cases, an exam situation was simulated with questions being asked and the answers being evaluated.

The type of tools offered to the user to search for specific cases or specific groups of cases is, in the learning resources investigated, diverse and in some cases a program will offer several of these tools. But a lot of programs offered no such tool.

Integration of Multimedia Elements

Video material was offered by three applications. None of the applications offered a zoom function. The opportunity to preview images using thumbnails to avoid unnecessary downloads, thus saving time, was offered three times.

Program Design

The adaptation and presentation of individual cases and findings varied from problem-based cases (which are processed by the user step by step), detailed case descriptions or image pairs for comparison with “normal” cases through to un-annotated presentations of findings.

A final check of the learning success was offered only by four applications in various ways.

Information regarding the date of the last update and thus the currency of the offer was only found on 14 sites.

The option of having the test results count towards ophthalmology courses in under- or postgraduate education or CPD (e.g. CME credits) was not offered on any site.

Discussion

The internet in its current state offers, due to its high acceptance by the public, access to information and data in a relatively simple way to a wide audience. This medium is therefore used by all eye clinics of German universities as a presentation platform for patient care, research and teaching. But it is not used for all these three areas equally. While some clinics mostly offer information for potential or actual patients or clients, others offer information to referring colleagues and others present the hospital as a research site.

As the centre of teaching, hospitals are under-represented on the internet, and only nine hospitals offer e-learning which goes beyond downloadable training materials.

Site Status

Reliable availability is common to all sites. This is due to the high quality of the network which in the academic and scientific domain is usually provided by well-organized, professional data centres.

Target Group

The evaluation of the target audience showed that only in a few cases the authors of a learning application provided information on the intended target group. Many offers appear to be suitable for multiple target groups but therefore also not optimized for anyone. A possible reason for this is that the authors might want to attract the widest audience possible and therefore keep the offer general. Another reason for this could be that no target group analysis was performed or that the need to address a particular target audience was overlooked when creating the learning application.

Targeting a specific group, however, appears necessary for the didactic structuring of learning provision, since the groups differ significantly in terms of their previous knowledge and learning needs. This problem could be resolved, for example by carrying out an initial target group analysis and a definition of the goals of the learning application.

Type of Program

The programs on offer can be divided into two groups: one group more or less clearly arranged collections of cases, quizzes with visual diagnoses or multiple choice questions.

For the most part, however, they lacked a consistent approach to problem-based learning. Only in a few exceptions could we identify characteristics of an educational program with a consistent didactic structure, appropriate for online use. As mentioned above, this lack could also be explained by the lack of a defined target group.

Program Content

The number of available images or cases varied greatly from offer to offer. The quality of the images and additional information given was equally varied. Although a set of standards exists for electronic publications in medicine [28], no site makes any reference to compliance with it. This reflects the fundamental problem information provided on the internet. In contrast to print media where peer review is common, there is currently no established quality control and verification of information. Whether validation and quality control of information on the internet is feasible is questionable but efforts are being made to verify data on offer on a voluntary basis through authorized bodies specifically set up for this purpose to underline the credibility of information [1], [2], [26]. The data of offer evaluated by this study only found 2 cases where images contained information about the author, and only one provided information regarding a second opinion by a physician.

The bulk of the material on offer hails from the respective hospitals. This is a simple and inexpensive solution for demonstrating everyday illnesses. However, relative to the size of the hospital and its associated patient population it becomes more or less difficult to offer images of rare diseases or differential diagnoses.

The basics of ophthalmology such as anatomy, embryology, physiology, biochemistry, genetics and optics were rarely addressed. One reason for this could be that the target group is assumed to have such base knowledge. Another reason could be that such knowledge is taken for granted by the authors, who are mostly doctors in training or specialists in ophthalmology, so it does not occur to them to mention it. The above mentioned identification of a specific audience for the application, and thus prior knowledge which can be assumed, would be desirable.

Treatment is only discussed in rare cases. Also conservative drug treatments and surgical techniques are rarely described. It can be assumed that the authors concentrating on describing pathology is the reason for not doing so. Whether the offers will be extended to include treatment aspects remains to be seen.

Program Structure

The structure of the individual applications naturally shows a considerable degree of variation. A logical sequence in the form of a gradual introduction to the diagnosis, e.g. in the form of obligatory diagnostic stages or presentation of pre- and postoperative images or a re-enactment of the diagnostic pathway accompanied by the experiences of the authors was the exception. Many programs provide only case collections or databases with more or less sophisticated search engines. Means of controlling the learning success at the end of a section are also not commonly available.

Technical Implementation

The way in which an application is implemented from a technical perspective to a large extent influences the user-friendliness, applicability, benefits and motivation of the learner. This raised the bar for the authors.

For example, general tools provide overviews of the cases on offer compared to search engines. There is also the possibility of using of direct support tools or so-called wizards, which guide the user through the program. Alternatively, help pages can be created which can be consulted prior to using the program or when searching for the answer to a question.

Tools for the user to personally structure learned material, such as virtual post-its or bookmarks, are a rarity. High resolution images (e.g. for download) were not provided by any site.

In a number of publications, we found a judicious use of multiple multimedia levels. This is in contrast to the findings of Seitz, Schubert et al. who only found a small number of multimedia elements available online for radiology courses in 2003. [30] One reason for this change is the increased capacity of modern internet connections which reduce the download time and therefore waiting times and interruptions of the learning process. The cost of connecting to the web in general has decreased and by now is seen as an insignificant factor with the increase of unlimited data transfer packages. However, to avoid unnecessary downloads, compressed and small-scale preview images (thumbnails) are often offered to enable pre-selection of content.

If a website is up to date, this has a considerable impact on its success. Yet only a minority of the sites makes any indication regarding recent updates. A successful learning resource, however, must be under continuous review and revised if necessary. In many cases, information is no longer current or kept very vague so indicating the date of the last update might not appear necessary.

Commercial Use

As free e-learning modules are already available on the evaluated sites, including websites of non-university providers, marketing commercial products does not seem and attractive strategy. Another point which speaks against commercial use undoubtedly lies in the high rate of illegal copies of licensed software. This point is underscored by the fact that there are no DVDs or CD-ROMs for e-learning in ophthalmology on the German-language market. [Springer, Georg Thieme Verlag, MVS Medizinverlage Stuttgart, Haug Verlag, Hippokrates Verlag, Enke Verlag, Sonntag Verlag, TRIAS, Haug Sachbuch; following personal communication and research]

Suggestions for the Production of Ophthalmological Learning Programs

Our study found a number of teaching platforms which satisfy pedagogical, didactic and ophthalmic requirements. All these programs were developed by interdisciplinary projects involving computer scientists, educators and medical professionals. These projects show promising approaches towards modern e-learning but again without having implemented all the detail which is desirable according to the existing literature.

A compelling proposition was found on the pages of the University of Tübingen [31]. Using multimedia, different case simulations are presented. [http://www.inmedea-simulator.net/] The learning application of the University Eye Hospital Freiburg links the cases presented to topics from classroom teaching is the first to integrate aspects of blended learning into undergraduate teaching.

A major disadvantage of such a labour-intensive design path for e-learning projects lies in the resulting personell expenditure. These projects were carried out through the participation of various funding support programs.

Conclusions

The availability of the ophthalmology websites at German university eye clinics is highly reliable. Except for one unsuccessful attempt, all pages were available.

In contrast to similar studies, such as Seitz, Schubert et al. [29] several pedagogically and didactically structured learning programs were found which were uniquely designed for a specific target group. The material found, however, spanned quite a wide range both in terms of quantity and quality.

The lack of learning applications which satisfy modern, technical and didactic requirements is alarming as it represents an under-use of an essential communication medium, and thus also a teaching and learning medium, by German university eye hospitals.

Offers at a high medical, educational and technological level have only been realized by larger projects. These included an interdisciplinary team with didactic, educational, programming and of course medical expertise. Small groups of medical staff of a university eye clinic or individuals appear to be overwhelmed with the complexity of the task and the workload, which is required in the creation of modern e-learning modules.

The option of completed e-learning counting towards degree courses in ophthalmology at university (e.g. OSCE credits) and in postgraduate education (e.g. CME points) was not offered by any application. Integrating such offers into such structures will surely increase the acceptance and demand for them.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

References

- 1.Akerman R. Technical solutions: Evolving peer review for the internet. Nature. Nature. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nature04997. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature04997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson C. Technical solutions: Wisdom of the crowds. Nature. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nature04992. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature04992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arden GB. The use of computers in ophthalmology: an exercise in futurology. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1985;104(Pt 1):88–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chumley-Jones HS, Dobbie A, Alford CL. Web-based learning: sound educational method or hype? A review of the evaluation literature. Acad Med. 2002;77(10 Suppl):86–93. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210001-00028. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200210001-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuendet JF, Gygax PH, Vergriete JC. Computer-aided teaching in ophthalmology. Doc Ophthalmol. 1977;43(1):11–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01569286. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01569286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devitt P, Smith JR, Palmer E. Improved student learning in ophthalmology with computer-aided instruction. Eye (Lond) 2001;15(Pt 5):635–639. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.199. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/eye.2001.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dick B, Pfeiffer N. Ophthalmological information services on the internet--an analysis of user hit. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1997;211(5):aA14–aA16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dick HB, Haberern G, Kuchenbecker J, Augustin AJ. Internetpräsenz und Homepagedesign für Augenärzte. Ophthalmologe. 2000;97(7):503–510. doi: 10.1007/s003470070083. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s003470070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dick HB, Zenz H, Eisenmann D, Tekaat CJ, Wagner R, Jacobi KW. Computer-assisted multimedia interactive learning program "Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma". Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1996;208(5):A10–A14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietel M. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Telemedizin. Forsch Lehre. 2001;4 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floto C, Huk T. Neue Medien in der Medizin: Stellenwert, Chancen und Grenzen. Dtsch Arztebl. 2002;99(27):A1875–1878. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folberg R, Dickinson LK, Christiansen RA, Huntley JS, Lind DG. Interactive videodisc and compact disc-interactive for ophthalmic basic science and continuing medical education. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(6):842–850. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(13)31567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman RB. Top ten reasons the World Wide Web may fail to change medical education. Acad Med. 1996;71(9):979–981. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199609000-00013. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199609000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handzel DM, Hesse L. „i-Doc – interaktive Differentialdiagnosen ophthalmologischer Kasuistiken“. Vortrag auf der Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Medizinische Ausbildung GMA „Qualität der Lehre“; Jena: Gesellschaft für Medizinische Ausbildung; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman D, Lee S. Formative evaluation of a multimedia CAL program in an ophthalmology clerkship. Med Teach. 1993;15(4):327–340. doi: 10.3109/01421599309006655. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01421599309006655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong J, Li X, Wang Y, Sun W, Zhang J. Effect of digital problem-based learning cases on student learning outcomes in ophthalmology courses. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1211–1214. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.110. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korff F. Internet für Mediziner. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuchenbecker J, Demeler U. Computeranwendungen in der Augenheilkunde. Ophthalmologe. 1997;94(3):248–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuchenbecker J, Parasta AM, Dick HB. Internet-basierte Lehre, Aus- und Weiterbildung in der Augenheilkunde. Ophthalmologe. 2001;98(10):980–984. doi: 10.1007/s003470170049. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s003470170049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuchenbecker J. Multimedia-Anwendungen für Augenärzte auf CD-ROM. Augenspiegel. 1999;45(7-8):56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JM, Koide MM, Salvador EM, Moura J, Ramos MP, Uras R, Matos RB, Jr, Anção MS, Sigulem D. Educational program on ophthalmology. Medinfo. 1995;8(Pt 2):1241–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lönwe B, Heijl A. Computer-assisted instruction in emergency ophthalmological care. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1993;71(3):289–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1993.tb07137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michelson G, Scibor M, Keppler K, Dick B, Kuchenbecker J. Augenärztliche Online-Fortbildung durch Live-Übertragungen und on-demand Vorträgen via Internet. Ophthalmologe. 2000;97(4):290–294. doi: 10.1007/s003470050530. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s003470050530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michelson G, Scibor M. Neue Kommunikationswege in der ärztlichen Fortbildung - Erste Erfahrungen von Live-Übertragungen augenärztlicher Kongresse im Internet. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1999;215(5):aA6–aA12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinmann-Rothmeier, G . Didaktische Innovation durch Blended Learning. Leitlinien anhand eines Beispiels aus der Hochschule. Bern: Huber Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz JG, Candler C, Teasdale TA. Peer reviewing e-learning: opportunities, challenges, and solutions. Acad Med. 2007;82(5):503–507. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803ead94. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803ead94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiefer U, Schiller J, Burth R, Schnerring W. Tuebingen Education System (TES): eine interaktive Falldemonstrationssoftware. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2002;219(8):597–601. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34422. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-34422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz S, Klar R, Auhuber T, Schrader U, Koop A, Kreutz R, Oppermann R, Simm H. Qualitätskriterienkatalog für elektronische Publikationen in der Medizin des Arbeitskreises "CBT" der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Medizinische Informatik, Biometrie und Epidemiologie (GMDS) Köln: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Medizinische Informatik, Biometrie und Epidemiologie; 1999. Available from: http://www.imbi.uni-freiburg.de/medinf/gmdsqc/d.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seemann O. Internet Guide Medizin/Zahnmedizin. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seitz J, Schubert S, Völk M, Scheibl K, Paetzel C, Schreyer A, Djavidani B, Feuerbach S, Strotzer M. Evaluation radiologischer Lernprogramme im Internet. Radiologe. 2003;43(1):66–76. doi: 10.1007/s00117-002-0836-9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00117-002-0836-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stahl A, Boeker M, Ehlken C, Agostini H, Reinhard T. Evaluation of an internet-based e-learning ophthalmology module for medical students. Ophthalmologe. 2009;106(11):999–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00347-009-1916-2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00347-009-1916-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szulewski A, Davidson LK. Enriching the clerkship curriculum with blended e-learning. Med Educ. 2008;42(11):1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03184.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]