Abstract

Background:

Screening tests on blood bags is important step for blood safety. In Iran, screening for HCV started from 1996. We decided to determine the new cases of hepatitis C in our thalassemic patients, after screening of blood bags was initiated and trace backing from recipients to find their donors.

Materials and Methods:

The study was done on patients with complete files for HCVAb test results. Only cases that had a positive HCVAb result following a negative result were considered as new cases. For trace backing, we recorded the blood transfusions’ date and the blood bags’ number from last negative test results (HCVAb) to the first positive test result. These data were sent to the transfusion center. The suspected donors were contacted and asked to be tested again in the transfusion center.

Results:

A total of 395 patients were studied; 229 (58%) males and 166 (42%) females. Mean age was 27.5 years. We had 109 HCV (27.5%) positive cases of whom 21 were infected after 1996. We traced the last five cases contaminated during 2003 and 2004. These five patients had 13, 10, 13, 12, and 6 donors, respectively (totally 54 donors were found). We proved the healthy state in 68.5% (37 of 54) of our donors population. Of them, 81% were repeated donors and 17 of 54 donors (31.5%) could not be traced (because of change in addresses). We did not have any HCV new cases after 2004.

Conclusion:

We could not prove HCV transmission from donors as the source of infection. Although parenteral transmission is always on top of the list in HCV infection, the possibility of hospital and/or nursing personnel transmission and/or patient-to-patient transmission such as use of common instruments like subcutaneous Desferal® infusion pumps; which the patients used for iron chelation therapy, should also be kept in mind.

Keywords: Hepatitis C, thalassemia, transfusion-transmitted infections

Introduction

Thalassemia is an inherited hemoglobinopathies disorder,[1,2] which is endemic in Tehran region. Blood transfusion is a necessary treatment for these patients. However, the blood transfusion has its own side effects. Main problems of blood transfusion are transfusion-transmitted infections, especially hepatitis C.[3,4] Prevention of such problem has been the first priority of blood transfusion organizations. For achieving this goal, they struggle to reduce the rate of the hepatitis C by accurate screening tests of donated blood.[5–10]

In Iran, the Hepatitis C Virus Antibody (HCVAb) screening tests based on the Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) method, has been necessitated since 1996. Nowadays, third generations of these kits are used and it caused reduction of newly infectious cases. In this survey, we decided to determine the new cases of hepatitis C in our thalassemic patients, after screening of blood bags was initiated in 1996. Then, we tried to find the source of infection (contaminated donors) by trace backing the blood bags.

This study was conducted on adult thalassemia clinic. This clinic is specific for thalassemia patients, under supervision of Iranian Blood Transfusion Organization (IBTO) and all needs of blood provided this center. Since these patients are regular users of the blood, it can be a reliable index of the prevalence of the hepatitis C after screening the donated blood.

Materials and Methods

Our descriptive study was approved by the IBTO committee. Written informed consent was obtained from patients, their parents or legal guardians in all cases. A cross-sectional examination was carried out on patients who had complete files with authentic information. Basic information such as age, sex, type of thalassemia, blood groups, and lab parameters like serum ferritin and Hepatitis C were extracted from their files. Particular attention was paid to hepatitis C and HCV Ab test results; the test dates were also registered. Only cases that had a positive HCV Ab result following a negative result in the clinic file were considered as new cases. Cases that had no test results prior to 1996, and whose first test available in the file was positive were not considered as new cases (In our center, all patients were checked for HCV every 6 months).

For trace backing of new cases, we recorded the blood transfusions’ date and the blood bags’ numbers from last negative test results (HCVAb) to the first positive test result. These data were sent to the blood transfusion center (IBTO) for following up of donors, which contacted based on the information were available in their files. To prove the hepatitis infection and the probability of its transmission from donors follow up was done accurately.

Since the contact information of the blood donors were limited in the center (because of changing addresses), and there were not complete donor data file available in transfusion center, so we had to trace back only the five last cases contaminated. All the necessary data belonging to these five patients who were contaminated between 2003 and 2004 were sent to the blood transfusion center. The suspected blood donors were contacted and asked to be tested again in the blood transfusion center.

SPSS (version 14) was used for data analysis. The mean, average, and standard deviation were calculated. P value <0.01 was considered as significant correlation between two parameters.

Results

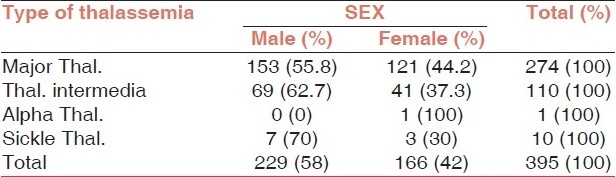

In this study, 395 cases who had reliable clinical documents were studied; the study group consisted of 229 (58%) males and 166 (42%) females. Of them, 274 (69.4%) patients were major thalassemia, 110 (27.8%) intermediate thalassemia, 10 (2.5%) sickle thalassemia, and 1 (0.3%) alpha thalassemia (HbH) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Frequency of our thalassemic patients according to sex

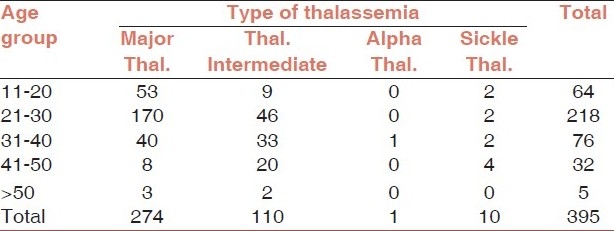

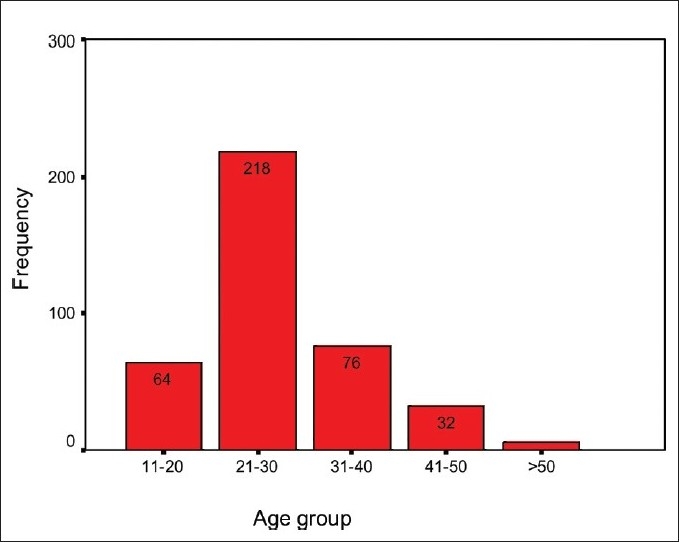

Mean age of the study group was 27.5 years (SD ± 7.99) and mean ferritin serum level was 1755.16 ng/ml (SD ± 1034.04). Age groups of patients is shown in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2.

Frequency of our thalassemic patients according to group

Figure 1.

Age grouping of thalassemic patients

A total of 252 patients (66.3%) were spelenectomized.

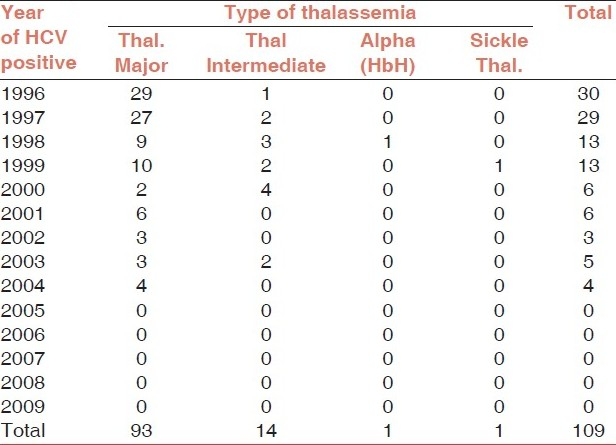

Some 109 out of 395 patients of the study population (27.5%) were infected with Hepatitis C. The year of diagnosis is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequency of HCV infection (year of diagnosis) in our patients according to type of thalassemia

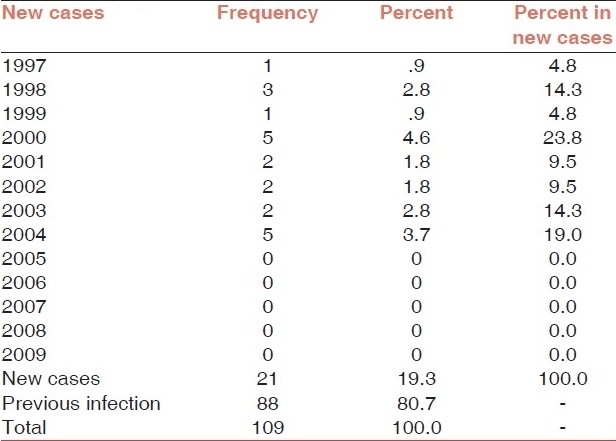

In this study, 21 out of 109 patients were hepatitis C positive after 1996; they had been negative before. Table 4 presents new hepatitis cases during this time. It is worth noting that we did not have any new hepatitis cases after 2004. There was a significant correlation between hepatitis and type of thalassemia (P = 0.044). However, there was not any correlation between newly diagnosed hepatitis cases and their thalassemia type (P = 0.193).

Table 4.

Frequency of new cases of HCV infection according to year of diagnosis

A total of 21 new cases out of 109 were contaminated after 1996. But there were no complete donor data file available in transfusion center, so we had to trace back only the five last cases contaminated. These five patients had 13, 10, 13, 12, and 6 donors, respectively (totally 54 donors were found for 5 HCV new cases). In our trace backing, we proved the healthy state in 68.5% (37 of 54) of our donors population. Approximately, 81% of these donors were repeated donors. However, few donors were not accessible (because of change in addresses) and hence 17 out of 54 donors (31.5%) could not be traced.

Table 5 is a sample tracing of one of our HCV new cases. He had 13 donors {In recording, the blood transfusions’ date and the blood bags’ numbers, from last negative test results (HCVAb) to the first positive test result}, but we cannot access to 5 out of 13 donors.

Table 5.

One sample of tracing the HCV new cases and recording the blood transfusions’ date and the blood bags’ numbers, and follow-up donors in transfusion center

Totally, we cannot show any correlation between the transmissions of hepatitis C from the blood donor to the recipients.

Discussion

Transfusion-dependent patients are more prone to acquiring various transfusion-transmitted infections such as Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), and Human Immune Deficiency Virus (HIV).[11] However, HBV and HIV can be transmitted, except blood transfusion, from a person to person, especially hepatitis B, which is transmittable from tears, urine, etc.[12,13] Screening tests for hepatitis C were discovered in 1990. Hepatitis C antibody (HCV Ab) screening test on donated blood bags was made compulsory from 1992 onwards.[14] In Iran, the hepatitis C screening test, i.e., HCV Ab ELISA test became obligatory for blood donations from 1996 and the third generation of ELISA since 1998.[15]

The prevalence of hepatitis C in Iran's public population is 0.3-1%.[16,17]

The reported prevalence of Hepatitis C in Iran's thalassemic patients is between 0.9-26.3%.[18–20] In other conducted surveys, this rate has been reported 13-34% in thalassemia population.[21–25] In the current study, 109/395 (27.5%) patients were positive for hepatitis C; this is not very different from a similar study conducted in the same center.[26] However, it is significantly higher than the figures reported in other centers in the country. This may be attributed to the fact that our clinic specific for adult thalassemic patients and the average age of our patients was 27.5 years. There were no thalassemic patients aged less than 11 in our study, and all patients had received transfusions before the hepatitis C screening had begun.

In this study, we tried to find the new cases of hepatitis C in our thalassemic patients, after screening of blood bags was initiated in 1996. We traced the new cases through the blood bag numbers and the information available in the transfusion centers. We managed to study 68.5% of the donors’ information and became certain of their bloods’ safety. However, we could not trace 31.5% of the donors because of change of address. So we could not prove transmission to be the source of infection. It may have two reasons; first, there were some donors that we were not able to trace them; we only could trace and prove that 68.5% of them were healthy. Then, we cannot conclude for sure that this hepatitis C transmission has occurred because of the donated blood. Second, this transmission may be because of the hospital or nosocomial infection or nursing personnel who are responsible for blood transfusion.[27,28] Such a transmission has been proved in dialysis patients. In one study, phylogenetic analysis of hepatitis C cases in hemodialysis patients, showed that infusion sets and/or cotton swabs, and even nurses who move from one bed to the other were recognized as other means of transmission.[29] However, such an event has not been proved in thalassemia patients, yet.

On the other hand, a complete information system about donors should be available in the blood transfusion system, It is also highly recommended that at least the donor's blood sample should be frozen (retention sample) and made available for such surveys. Moreover, various transmission factors should be controlled in hospitals and clinical centers in order to the rate of hepatitis transmission be reduced.

Conclusion

In this survey, we studied newly diagnosed hepatitis C by trace backing of the donated blood bags’ numbers in order to find carrier donors. However, we could not conclude that transmission of hepatitis C is because of the donated blood. We need a complete filing system for donors in blood transfusion centers. It seems that having repeated blood donors is safer for reducing the rate of hepatitis C, in parallel of performing accurate screening tests on donated bloods.

Even though parenteral transmission is always on top of the list during hepatitis C infection, but the possibility of hospital and/or nursing personnel transmission and/or patient-to-patient transmission such as use of common instruments like subcutaneous Desferal infusion pumps; which the patients used for iron chelation therapy, should also be kept in mind.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their colleagues in Vesal blood transfusion center, especially Dr. Attarchi for her valuable collaboration for this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Weathrall DJ, Clegg JB. 4th ed. USA: Black well science; 2001. The thalassemia syndromes; pp. 80–110. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rund D, Richmilewitz E. Pathophysiology of α and β thalassemia: Therapeutic implication. Semin Hematol. 2001;38:343–9. doi: 10.1016/s0037-1963(01)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azarkeivan A, Ahmadi MH, Hajibeigi B, Gharebaghian A, ShabehPour Z, Maghsoodlu M. Evaluation of transfusion reactions in thalassemic patients referred to the Tehran adult Thalssemia clinic. J Zanjan Fac Med. 2008;1:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodnough LT. Risks of blood transfusion. (v).Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2005;23:241–52. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger EP, Anaya DA. Infectious and immunologic consequences of blood transfusion. Crit Care. 2004;8(Suppl 2):S18–23. doi: 10.1186/cc2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiebig EW, Busch MP. Emerging infections in transfusion medicine. (viii).Clin Lab Med. 2004;24:797–823. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tawk HM, Vickery K, Bisset L, Lo SK, Cossart YE. The significance of transfusion in the past as a risk for current hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection: A study in endoscopy patients. Transfusion. 2005;45:807–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatachary DI, Bhatacharjee S, De M, Lahiri P. Prevalence of HCV in transfusin dependent Thalassemia and Hemophilia. Indian J Med Res. 1991;94:430–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.el-Nanawy AA, el Azzonni OF, Soliman AT, Amer AE, Demian RS. Prevalence of HCV and HBV in healthy Egyptian children and four high risk group. J Trop pediatr. 1995;41:341–3. doi: 10.1093/tropej/41.6.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung JL, Kao JM, Kong MS, Yang CP, Hung IJ, Lin TY. Hepatitis C in polytransfused children. Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156:546–9. doi: 10.1007/s004310050659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Androulla E. Nicisia, Cyprus: Thalassemia International Federation (TIF); 2007. Guidelines to clinical management of thalassemia; pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feigin RD, Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL. Text book of pediatric infections disease. 6th ed. Saunders/Elsevier: 2009. Viral hepatitis due to hepatitis A-E and GB viruses; pp. 1875–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cano H, Candela MJ, Lozano ML, Vicente V. Application of a new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of total hepatitis C virus core antigen in blood donors. Transfus Med. 2003;13:259–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2003.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rezvan H, Abolghassemi H, Kafiabad SA. Transfusion-transmitted infections among multitransfused patients in Iran: A review. Transfus Med. 2007;17:425–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2007.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alavian SM, Ahmadzadasl M, Lankarani K, Shahbabaie M, Ahmadi A, Kabir A. Hepatitis C Infection in the General Population of Iran: A Systematic Review. Hepatitis Mon. 2009;9:211–23. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alavian SM, Adibi P, Zali MR. Hepatitis C virus in Iran: Epidemiology of an emerging infection. Arch Iran Med. 2005;8:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mirmomen S, Alavian SM, Hajarizadeh B, Kafaee J, Yektaparast B, Zahedi MJ, et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus infecions in patients with beta-thalassemia in Iran: A multicenter study. Arch Iran Med. 2006;9:319–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jamal R, Fadzillah G, Zulkifli SZ, Yasmin M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, CMV and HIV in multiply transfused thalassemia patients: Results from a thalassemia day care center in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:792–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javadzadeh H, Attar M, Taher Yavari M. Study of the prevalence of HBV, HCV, and HIV infectionin hemophilia and thalassemia population of Yazd (Farsi) Khoon (Blood) 2006;2:315–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadivar MR, Mirahmadizadeh AR, Karimi A, Hemmati A. The prevalence of HCV and HIV inthalassemia patients in Shiraz, Iran. Med J Iran Hosp. 2001;4:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karimi M, Yarmohammadi H, Ardeshiri R, Yarmohammadi H. Inherited coagulation disorder in Southern Iran. Hemophilia. 2002;8:740–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2002.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khamispoor Gh, Tahmasebi R. Prevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis in high risk groups ofBushehr province. Iran South Med J. 1999;1:59–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farzaadegan H, Shams zad M, Noori Arya K. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis among Iranian Population – a viral marker study. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1980;9(2):144–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akbari A, Imanieh MH, Karimi M, Tabatabaee HR. Hepatitis C Virus Antibody Positive Cases in Multitransfused Thalassemic Patients in South of Iran. Hepatitis Mon. 2007;7:63–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabbani A, Azarkeivan A, Farhadi LM, Korosdari Gh. Clinical Evaluation of 413 Thalassemic patients. J Fac Medicine. 2000;3:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alavian SM. Control of Hepatitis C in Iran: Vision and Missions. Hepatitis Mon. 2007;7:57–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alavian SM, Gholami B, Masarrat S. Hepatitis C risk factors in Iranian volunteer blood donors: A case-control study. J Gastroenterol and Hepatol. 2002;17:1092–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samimi-Rad K, Shahbaz B. Hepatitis C virus genotypes among patients with thalassemia and inherited bleeding disorders in Markazi province, Iran. Haemophilia. 2007;13:156–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]