Abstract

Genital tuberculosis is fairly common in Indian women due to high prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis in the general population. Histopathological diagnosis is invaluable but often, diagnosis can be made with reasonable accuracy by Papanicolaou (Pap) smear test if the index of suspicion is kept high. Also, genital tuberculosis is considered to be more common in patients less than 40 years of age and rare after menopause. We describe two cases of cervical tuberculosis in patients over 40 years of age, including a postmenopausal case, diagnosed by smear tests and later confirmed by histopathology and bacteriology. The differential diagnoses as well as problems encountered in the diagnosis of a tuberculous lesion in Pap smears are also discussed.

Keywords: Genital tuberculosis, menopausal, Pap smear

Introduction

Genital tuberculosis accounts for 0.75–1.0% of gynecological admissions in India,[1] with a rising incidence in the industrialized and developing countries, partly as a result of its association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. It is considered to be more common in patients less than 40 years of age and rare after menopause as the atrophic postmenopausal endometrium is thought to be poorly supportive of tubercle bacilli. Of late, however, the peak incidence has shifted to the postmenopausal women (as in one of our cases) and infertility has been superseded by abnormal uterine bleeding and pelvic pain as dominant complaints, particularly in the developed countries.[2] It occurs mostly secondary to hematogenous spread in cases of pulmonary tuberculosis. The fallopian tubes are most commonly affected, followed by endometrium, ovaries, cervix, vagina and vulva.[3] Tuberculosis of cervix without involvement of rest of the internal genitalia is very rare.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 41-year-old Indian multiparous lady complained of post-coital bleeding since 8 months, with history of pulmonary tuberculosis in the husband, who took anti-tuberculous treatment 7 years back and was cured. Per vaginum and per speculum examinations showed fixed, hard and retroverted uterus, free fornices and cervical erosion. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was raised. Abdominal ultrasound and chest radiograph were normal. Sputum and urine were negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB). Papanicolaou (Pap) smears were taken, followed by cervical and endometrial biopsies.

Case 2

A 45-year-old multiparous postmenopausal Indian female presented with complaints of post-coital bleeding and blood-stained vaginal discharge. Per vaginum examination showed thickened cervix with nabothian follicles and nodules in fornices. Per speculum examination revealed a small growth on the inner lip of cervix that bled on touch. Simultaneous per vaginum and per rectum palpation showed no thickening of recto-vaginal septum. ESR was increased. Abdominal ultrasound and chest radiograph were normal. Sputum and urine were negative for AFB. Clinical diagnosis of carcinoma cervix was made. Pap smears were taken, followed by cervical and endometrial biopsies.

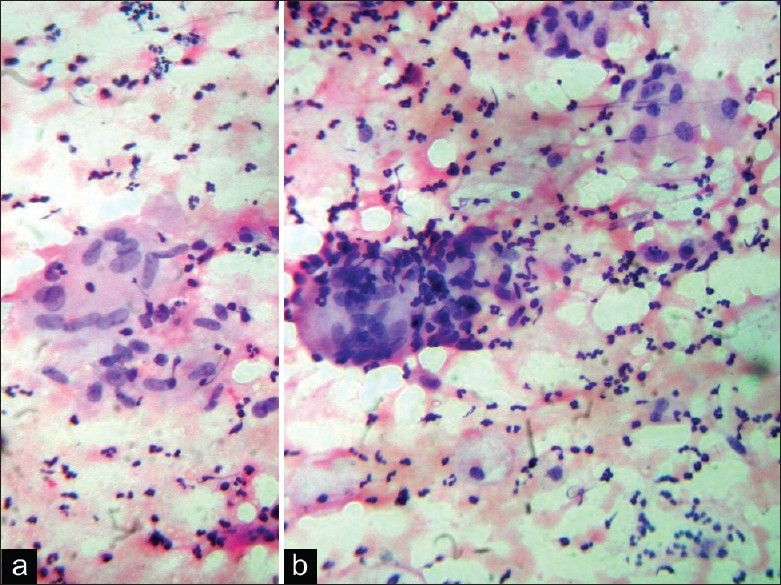

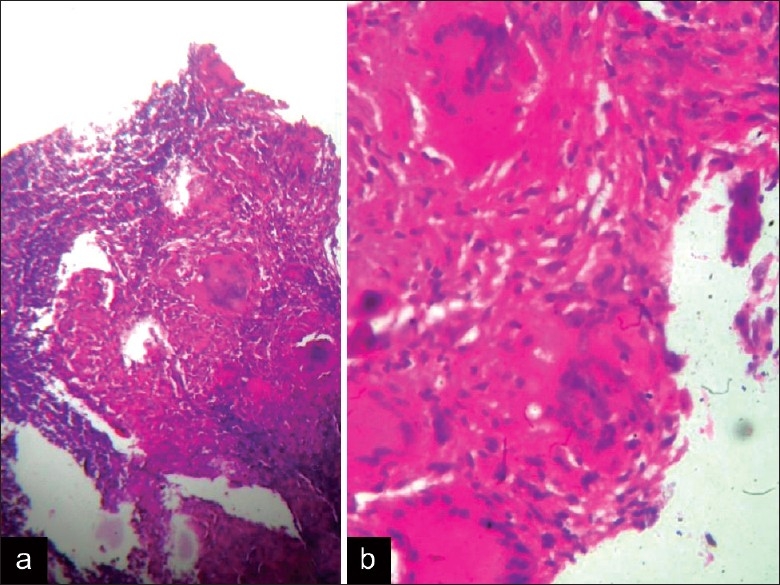

Microscopic examination of Pap smears of Case 1 and Case 2 showed granulomas composed of several clusters of epithelioid cells with pale vacuolated cytoplasm and round or oval nuclei, having thin nuclear membrane and fine ground glass chromatin [Figure 1a]. Occasional macrophages, lymphocytes and Langhans’ giant cells [Figure 1b] were also present along with focal (Case 1)/confluent large (Case 2) necrotic material. Pap smears were negative for AFB. Histopathological examinations of cervical biopsies of both the cases were consistent with tuberculous cervicitis [Figure 2b], while that of endometrial biopsies were consistent with tuberculous endometritis [Figure 2a]. Endometrial biopsy sections of both the cases and cervical tissue sections of Case 2 were positive for AFB, while cervical biopsy sections of Case 1 were negative.

Figure 1.

(a) Tuberculous granulomas in Pap smear (Pap, × 400); (b) Langhans’ giant cell (Pap, × 400)

Figure 2.

(a) Tuberculous endometritis (H and E, × 100); (b) Tuberculous cervicitis (H and E, × 400)

Discussion

Although culture methods are still the gold standard in the detection of genital tuberculosis, they are negative in about one-third of cases.[4] Hence, the diagnosis often depends mainly upon the cytological and histopathological examination. Pap smear examination may provide important tentative diagnosis and is often the only diagnostic aid available, especially at peripheral centers where taking smears and sending them to higher centers for cytology is easier than making specific laboratory or radiological investigations available. Not just cervical tuberculosis, even endometrial tuberculosis without cervical lesion can also be suspected in Pap smears, as observed by Highman,[5] who stressed that the presence of epithelioid cells in smears obtained in the second half of cycle should raise the suspicion of tuberculous endometritis as granulomas from the endometrial lesion may appear in Pap smears just before the onset of menstruation because it takes about 2 weeks for granulomas to form.

The pattern of tuberculous cervicitis in Pap smears must be distinguished from tissue repair and ulceration, either of which may accompany any chronic cervical lesion. Smears in the tissue repair show ragged sheets of reactive epithelial cells, having enlarged nuclei with prominent nucleoli, and nonspecific inflammation in the background. Langhans’ giant cells, with nuclei polarized at the periphery of cytoplasm, are less often seen. Instead, giant cells associated with reparative changes are seen, which have more central nuclei and may contain ingested material. Other types of multinucleated cells are easily distinguished. Those due to herpes virus show their epithelial origin and have smaller numbers of nuclei, showing the characteristic crowding and molding without overlapping, and may have eosinophilic inclusions in nuclei and cytoplasm. Very rarely, syncytial trophoblastic giant cells are found in cervical Pap smears, which are round or irregularly shaped. Their nuclei, having coarse chromatin, are uniformly distributed or gathered together at one end of the cell, lying in pale blue fluffy cytoplasm.

In our experience, the cytologist should be careful not to confuse the epithelioid cell-like cytological changes seen in clusters of proliferating fibroblasts in cases of non-tuberculous florid repair processes of cervix with the morphology of tuberculous granulomas. Sometimes, presence of associated necrotic foci in the background further complicates it. However, typical Langhans’ giant cells are missing although foreign body giant cells may be present. Rarely, exclusion of tuberculosis or its distinction from a healing non-tuberculous chronic cervical lesion is quite difficult. Histopathological confirmation is needed in such cases.

Other differential diagnoses of tuberculosis on Pap smear examination of cervical smears include chronic pelvic inflammation, mycotic infection, enterobiasis, lipid salpingitis, and carcinoma.[3] At times, foreign body reaction can be an important source of confusion, such as oil granulomas following hysterosalpingogram, catgut reaction in cases of previous surgery and insertion of intrauterine contraceptive device. Confusion of tuberculosis with dysplasia is not uncommon as in our case (Case 2). A bulky, necrotic cervix with parametrial thickening in pelvic tuberculosis often elicits an initial diagnostic impression of carcinoma of cervix. Even colposcopic findings might be confusing as both types of lesions may give rise to mosaic vascular pattern. In cases of malignancies, the problem is often convincingly resolved by Pap smear examination showing cytological features of dysplasia/malignancy in at least few clusters, evidence of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) infection, single cells in the background with dysplastic/malignant features and tumor diathesis. However, one should not confuse florid reactive changes in metaplastic, endocervial or even epithelioid cells with atypical cells in cases of tuberculous cervicitis, a phenomenon, which in our experience, is fairly common. Nuclear chromatin criteria must be strictly followed to rule out dysplasia. Histopathological examination of cervix is necessary in suspicious cases.

It should be noted that AFB are not always demonstrable in cytological smears.[6] Pap smears and even cervical or endometrial biopsy sections may often be AFB negative in a case of tuberculous cervicitis/endometritis. The tissue changes leading to better AFB yield are extensive tissue necrosis, liquefaction and micro-abscess formation.[7] Under such circumstances, the presence of typical epithelioid granulomas with Langhans’ giant cells is sufficient for diagnosis if other causes of granulomatous cervicitis/endometritis are excluded.

Pap smears might be normal despite the presence of a cervical or endometrial tuberculous lesion because of inherent problems with Pap smears like faulty technique, non-inclusion of representative area(s), lack of proper preservation, etc. Hence, cervical smears are helpful in making diagnosis of genital tuberculosis but do not negate it if smears are normal.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Arora R, Rajaram P, Oumachigui A, Arora VK. Prospective analysis of short course chemotherapy in female genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1992;38:311–4. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(92)91024-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Güngördük K, Ulker V, Sahbaz A, Ark C, Tekirdag AI. Postmenopausal tuberculosis endometritis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2007;2007:27028. doi: 10.1155/2007/27028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowdhury NN. Overview of tuberculosis of the female genital tract. J Indian Med Assoc. 1996;94:345–6,361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agrawal S, Madan M, Leekha N, Raghunandan C. A rare case of cervical tuberculosis simulating carcinoma cervix: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:161. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Highman WJ. Cervical smears in tuberculous endometritis. Acta Cytol. 1972;16:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishore B, Khare P, Gupta RJ, Bisht SP. Fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of inflammatory lesions of the breast with emphasis on tuberculous mastitis. J Cytol. 2007;24:155–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty S, Chakraborty AK, Patra SP, Bhattacharyya SK. Demonstrations of acid-fast bacilli in tissues and evaluation of atypical tuberculous lesion. J Indian Med Assoc. 1993;91:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]