Abstract

Introduction: Early adulthood has been suggested as the most relevant time to determine the influence of testosterone on prostate carcinogenesis. For a more detailed assessment of this hypothesis, the present study examined whether serum total or free testosterone in young men was more closely associated with prostate cancer disparities.

Methods: A literature search was conducted for studies that reported both total and free testosterone levels for population samples of young men, along with prostate cancer incidences for the populations from which study populations were sampled. A previously developed analytical method was used to standardize the hormone levels of 19 population samples gathered from nine studies, and these standardized values were compared with disparities in prostate cancer incidence.

Results: Population differences in total testosterone levels were significantly associated with prostate cancer disparities, r = 0.833, p = 0.001, as were population differences in free testosterone, r = 0.661, p = 0.027. After controlling for age differences, total and free testosterone remained associated with prostate cancer disparities, partial r = 0.888, p < 0.001, and partial r = 0.657, p = 0.039, respectively. A marginally significant difference existed in the strength of relationships between total and free testosterone with respect to prostate cancer disparities, with total testosterone exhibiting a stronger association, T2 = 1.573, p = 0.077.

Conclusions: Across analyses, total testosterone demonstrated a more robust relationship than free testosterone with cancer disparities, which may suggest that total testosterone is the more sensitive biomarker for evaluating androgenic stimulation of the prostate gland.

Keywords: age-related testosterone decline, hormone-dependent disease, prostate cancer disparities, total and free testosterone

Introduction

The steroid hormone testosterone is fundamental to growth and regulation of the prostate gland [Hsing, 2001; O’Malley, 1971]. Testosterone is delivered to the prostate through circulation, where it is largely metabolized into a more potent androgenic form dihydrotestosterone, which promotes cellular proliferation of prostatic epithelium [Hsing, 2001]. Although androgens are often implicated in the development of prostate cancer, clinical evidence for this association has been mixed [Platz and Giovannucci, 2004; Grönberg, 2003; Hsing, 2001]. An extensive meta-analysis of 18 prospective studies of men with prostate carcinoma compared with similarly aged controls found no significant relationship between levels of endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer risk [Roddam et al. 2008]. However, studies included in this analysis measured sex steroid hormones in late middle-aged and elderly men when intra- and inter-population variation in testosterone levels is least detectable, such that later life would not be the most appropriate period for comparative analyses of men’s testosterone profiles [Alvarado, 2010; Grönberg, 2003]. Previous research has found a relationship between testosterone levels during early adulthood and prostate cancer risk, suggesting that testosterone production in young men more appropriately captures relative differences in cumulative hormone exposure [Alvarado, 2010]. Indeed, levels of sex steroids decline at later ages in both men and women, and ecological studies testing the relationship between young adult steroid concentrations and the risk of hormone-sensitive cancers have reported strong associations for both sexes [Alvarado, 2010; Jasieńska and Thune, 2001; Jasieńska et al. 2000].

Total and free testosterone measures are frequently reported in the epidemiological and oncological literature, but the functional significance of these different measures is rarely investigated. Free steroids are lipid-soluble molecules that diffuse across cell membranes to interact with specific endocellular receptors, but must bind to carrier proteins for transport in peripheral circulation. Most serum testosterone is bound to two primary carrier proteins, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and albumin, with only a small fraction of testosterone circulating in free form. SHBG binds testosterone with high affinity, rendering the molecule biologically inactive. In contrast, the binding affinity of albumin is several orders of magnitude less, and albumin-bound testosterone is able to dissociate from its bond for entry into target tissues [Matsumoto, 2001].

Total testosterone is a cumulative measure of circulating testosterone that includes both diffusible and protein-bound forms, whereas free testosterone is often regarded as a direct assessment of physiological availability [Rosner et al. 2007; Matsumoto, 2001]. Two methods widely used for determining free testosterone levels within circulation are radioimmunoassay (RIA) of an analog ligand to directly estimate free testosterone (direct RIA), and the calculation of free testosterone from total testosterone and the concentration of immunoassayed plasma proteins (calculated free testosterone) [Rosner et al. 2007; Vermeulen et al. 1999]. Experimental comparisons of laboratory methods have shown that calculated free testosterone produces reliable hormone values; however, direct RIA of free testosterone was found to be an inaccurate and inconsistent procedure [Rosner et al. 2007; Vermeulen et al. 1999; Winters et al. 1998], leading some researchers to question the continued use of this assay [Rosner, 2001].

In addition to free testosterone, estimations of physiologically available testosterone are often reported in the literature, most notably, ‘bioavailable’ testosterone and free androgen index (FAI). FAI is a unitless quotient representing the concentration of total testosterone/the concentration of SHBG [Rosner et al. 2007]. FAI has repeatedly shown poor correlations with free testosterone measures, especially for men [Morris et al. 2004; Kapoor et al. 1993]. In contrast, bioavailable testosterone is the combined portion of free and albumin-bound testosterone and has shown strong correlations with other validated measures of free testosterone [Rosner et al. 2007; Morris et al. 2004; Morely et al. 2002; Vermeulen et al. 1999].

A recent meta-analysis of studies reporting hormone levels for population samples of young men in relation to prostate cancer disparities found a positive, significant association between men’s total testosterone levels and prostate cancer incidence [Alvarado, 2010]. It seems reasonable to expect that free testosterone would demonstrate a more robust relationship with cancer disparities than would total testosterone, given that free testosterone is able to diffuse into prostatic cells and support cell proliferation [Feldman and Feldman, 2001]. To the contrary, some studies have found significantly higher total testosterone levels in men from populations with an increased risk of prostate cancer while failing to find this relationship using free form measures of testosterone [Kehinde et al. 2006; Winters et al. 2001; Santner et al. 1998]. As such, the purpose of this examination was to formally test whether disparities in prostate cancer risk are more closely associated with young men’s total or free testosterone measures in studies using assay procedures that are generally considered acceptable for healthy adult males.

Methods

A literature review was completed for studies reporting testosterone levels of presumably healthy men from population samples with a mean or median age of less than 39 years, so that the influence of age-related testosterone decline was reduced. The author searched PubMed for articles using the terms: androgen, epidemiology, prostate cancer, sex hormones, steroids, testosterone, ethnicity, and race. In addition, a manual search of bibliographies from the retrieved articles was completed. Some hormone datasets were reproduced within multiple publications, but only a single representation of each was used. Only studies reporting both total and free testosterone measures were included in this analysis.

Nine studies reporting testosterone values for 19 population samples were gleaned from the published literature. Each study compared two or more groups of men. Population samples were generally apportioned according to ethnicity and geographic residence: Americans of African, Caucasian, and Mexican ancestry from several regions within the United States as well as men from China, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and Sweden. Age-standardized rates of prostate cancer incidence were collected from the regional population in which study samples were recruited. Cancer rates were gathered from a worldwide collection of cancer registries compiled within the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Vol. IX database [Curado et al. 2007]. Every effort was made to match cancer incidences with the corresponding location and ethnicity of study samples, which was particularly important for US samples considering the extensive diversity of the American populace. See Table 1 for a descriptive summary of included studies.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of population samples.

| Study | Age1 | Sample Size | Ethnicity | Population | Prostate cancer incidence: region/population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ettinger et al. [1997]2 | 30.7 | 109 | African-American | Birmingham, Chicago, | USA (SEER): African-American |

| 31.3 | 114 | Caucasian-American | Minneapolis, Oakland: USA | Caucasian-American | |

| Jakobsson et al. [2006] | 18.9 | 122 | Swedish | Gothenburg, Sweden | Sweden |

| 26.3 | 74 | South Korean | Incheon, South Korea | Incheon, South Korea | |

| Lewis et al. [2005]3 | 26.6 | 60 | Japanese | Japan | Miyagi Prefecture, Japan |

| 25.8 | 60 | New Zealander | New Zealand | New Zealand | |

| Lookingbill et al. [1991] | 25.9 | 53 | Hong Kong Chinese | Hong Kong | Hong Kong |

| 23.7 | 57 | Caucasian-American | Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA | Pennsylvania, USA: Caucasian | |

| Rohrmann et al. [2007] | 28.6 | 239 | Mexican-American | USA national sample | USA (SEER): Hispanic White |

| 29.5 | 206 | African-American | African-American | ||

| 31.8 | 252 | Caucasian-American | Non-Hispanic White | ||

| Ross et al. [1986] | 20.6 | 50 | African-American | Los Angeles, USA | Los Angeles County, USA: |

| 19.9 | 50 | Caucasian-American | African-American | ||

| Caucasian-American | |||||

| Santner et al. [1998]4 | 22–27 | 10 | Caucasian-American | Pennsylvania, USA | Pennsylvania, USA: Caucasian |

| 24–39 | 10 | Chinese | Beijing, China | Shanghai, China | |

| Tsai et al. [2006] | 34 | 357 | African-American | San Francisco–Oakland, | San Francisco Bay area, USA: |

| 33.5 | 618 | Caucasian-American | USA | African-American | |

| Caucasian-American | |||||

| Winters et al. [2001] | 19.8 | 23 | African-American | Pittsburgh, USA | Pennsylvania, USA: |

| 21.5 | 23 | Caucasian-American | African-American | ||

| Caucasian-American |

Unless age range is indicated, mean age is reported for study samples, with the exception of Rohrmann et al. [2007] and Tsai et al. [2006] for which median age is reported.

Ettinger and colleagues reported testosterone values for urban centers in a multiregional United States sample. To approximate this population, national incidences of prostate cancer were obtained from SEER registries in CI5 IX, which are also more urban than a representative sample of the US populace (SEER, 2005).

A nation-level incident rate of prostate cancer for Japan was not available from CI5 IX, though cancer incidences were available for some Japanese prefectures. Using incident rates from different reporting prefectures, or an average value from all prefectures, had no appreciable effect on analyses.

Prostate cancer incidence for Beijing was not available. Shanghai was used to approximate an urban Chinese population. Santner and colleagues also reported testosterone levels for a study sample of Pennsylvanian men of Chinese ancestry, but an incident rate of prostate cancer was not available for this population, nor was there an obvious approximation of this to use in analyses.

Of the retrieved articles that met the specified criteria, there were studies excluded because of methodological limitations. As reviewed earlier, some immunoassay procedures have recognized problems; direct RIA of serum free testosterone and FAI have been shown to produce unreliable values for men [Rosner et al. 2007; Vermeulen et al. 1999; Kapoor et al. 1993]. Studies employing either of these methods were eliminated from the dataset, resulting in the exclusion of two studies [Kehinde et al. 2006; Wright et al. 1995]. One other study was excluded due to inadequacies of hormone analysis procedures. In this study [Ross et al. 1992], newly acquired serum samples were compared with older specimens that were reanalyzed after storage for an extended period of time, which is methodologically problematic [Bolelli et al. 1995]. Also, hormone values from the older specimens in this study were reported within an earlier publication [Ross et al. 1986].

Studies included in the current analysis spanned more than two decades. Consequently, immunoassay procedures used to analyze hormone samples differed across nearly all of these studies, and a high degree of measurement variability among competing testosterone assays made direct comparisons of hormone levels between studies impossible [Boots et al. 1998]. To standardize these data so that an aggregate dataset could be constructed, a comparison of ratios was calculated in which the proportional difference of mean testosterone levels between population samples within a study was compared with the proportional disparity in prostate cancer incidence for populations from which study populations were sampled. This analytical method was developed previously [Alvarado, 2010] and can be expressed formally as follows:

|

Each value within this dataset represents a pairwise comparison of population samples from within a study. If a value were graphically represented, the data point would reference the proportional dissimilarity in testosterone between population samples on the x-axis, relative to the proportional disparity of prostate cancer on the y-axis. See Table 2 for calculations.

Table 2.

Data and calculations for population samples.

| Study | Proportional difference in total testosterone levels1 | Proportional difference in free testosterone levels2 | Proportional disparity in prostate cancer incidence (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ettinger et al. [1997] | AA/CA (ng/dl): 595/549 = 1.08 | AA/CA: 152/138 (pg/ml) = 1.10 | AA/CA: 190.1/116.0 = 1.64 |

| Jakobsson et al. [2006] | SWE/KOR (nmol/l): 18/14.4 = 1.25 | SWE/KOR: 13.4/10.8 = 1.24 | SWE/KOR: 84.6/7.8 = 10.85 |

| Lewis et al. [2005] | JPN/NZ (nmol/l): 30.5/29.1 = 1.04 | JPN/NZ (pmol/l): 803/710 = 1.04 | JPN/NZ: 22/104.4 = .21 |

| Lookingbill et al. [1991] | HK/CA (umol/l): 20/19.5 = 1.03 | HK/CA: 8.4/9 = .93 | HK/CA: 15/110 = .14 |

| Rohrmann et al. [2007]3 | MA/AA (ng/ml): 5.55/5.35 = 1.04 | MA/AA (ng/ml):.113/.107 = 1.06 | HA/AA: 90.8/178.8 = .51 |

| MA/CA: 5.55/5.17 = 1.07 | MA/CA:.113/.104 = 1.09 | HA/CA: 90.8/112.3 = .81 | |

| AA/CA: 5.35/5.17 = 1.03 | AA/CA:.107/.104 = 1.03 | AA/CA: 178.8/112.3 = 1.59 | |

| Ross et al. [1986] | AA/CA (pg/ml): 6,605/5,569 = 1.19 | AA/CA (pg/ml): 166/137 = 1.21 | AA/CA: 186.4/109.3 = 1.71 |

| Santner et al. [1998] | CA/CHN (ng/dl): 640/480 = 1.33 | CA/CHN (ng/dl): 280/240 = 1.17 | CA/CHN: 110/6.9 = 15.94 |

| Tsai et al. [2006]4 | AA/CA (ng/dl): 693.5/611.5 = 1.13 | AA/CA (ng/d): 427.75/381.75 = 1.12 | AA/CA: 155.8/118 = 1.32 |

| Winters et al. [2001] | AA/CA (ng/dl): 673/538 = 1.26 | AA/CA (pmol/l): 215/208 = 1.03 | AA/CA: 180.6/110 = 1.64 |

The original units of measurement as reported in the literature were retained so that testosterone values could be referenced.

Jakobsson et al. [2006] and Lookingbill et al. [1991] reported bioavailable testosterone, while all other studies reported free testosterone levels.

Rohrmann and colleagues reported testosterone values after controlling for anthropometry and lifestyle factors.

Tsai and colleagues reported longitudinal data for study samples, which were divided into prostate cancer cases and controls as well as by ancestry. Testosterone values for the earliest age reported were averaged between case and control groups for each ancestral group, and these values was used in analyses.

Population comparisons among 19 samples were analyzed, but employing within-study contrasts as the basic unit of analysis produced a dataset consisting of 11 values. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to test for an association between population differences in testosterone levels and prostate cancer incidences. Population samples included in this dataset were relatively young, but it was still conceivable that age differences could exert an influence on subsequent analyses. See Table 1 for the ages of population samples. To address this concern, an average of the reported ages for each population comparison was calculated (or an average of midpoints when age ranges were reported), and population disparities of testosterone levels and prostate cancer were reanalyzed using partial correlation to control for age. All comparative population data were log transformed to better adhere to the parametric assumptions of Pearson’s and partial correlation. Tests were two-tailed.

Williams T2 statistic [Steiger, 1980; Williams, 1959] was used to determine whether a significant difference existed in the relative strength of the association between total and free testosterone in relation to prostate cancer disparities. Population comparison values were age-adjusted and log transformed for this analysis, as well. A one-tailed test was performed because of the limited statistical power of the small sample size (n = 11), along with conservative nature of the Williams T2 statistic.

Results

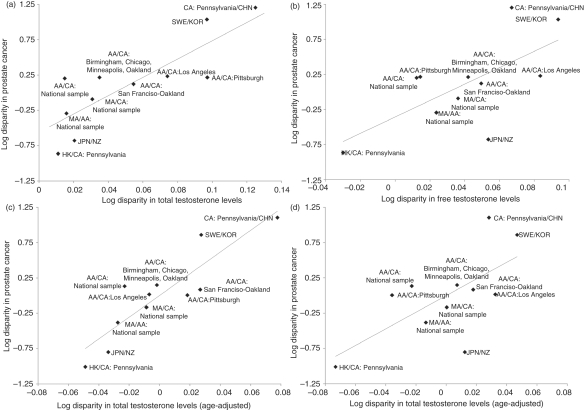

Population differences in total testosterone levels of young men were associated with population disparities in prostate cancer incidence, r(9) = 0.833, p = 0.001, as were population differences in free testosterone, r(9) = 0.661, p = 0.027. When age differences of the study samples were controlled for, total and free testosterone levels remained significantly associated with population disparities in prostate cancer incidence, partial r = 0.888, df = 8, p < 0.001, and partial r = 0.657, df = 8, p = 0.039, respectively. See Figure 1 for a graphical representation of these relationships.

Figure 1.

Proportional disparity in prostate cancer incidence with respect to proportional disparity in (a) total testosterone, y = 12.96x – 0.56, R2 = 0.69, and (b) free testosterone, y = 11.68x – 0.36, R2 = 0.44. After adjustment for age, proportional disparity in prostate cancer incidence with respect to proportional disparity in (c) total testosterone y = 15.37x + 0.00, R2 = 0.79, and (d) free testosterone, y = 11.78x + 0.00, R2 = 0.43. Population comparison values were log transformed. Abbreviations for population samples: AA, African-American; CA, Caucasian-American; MA, Mexican-American; CHN, Chinese; JPN, Japanese; KOR, South Korean; NZ, New Zealander; SWE, Swedish. Data points were labeled according to the ethnicity and region of population samples.

It should be noted that the preceding analyses contained many direct population comparisons between African- and Caucasian-Americans (AA/CA). Although these comparisons were made among different regional populations within the United States, which vary greatly in their disparity in testosterone levels and prostate cancer (Table 2), there was still potential for generating a biased outcome based on an overrepresentation of AA/CA comparisons. As such, a dummy variable was created that represented whether a comparison value was an AA/CA comparison. Controlling for the influence of whether a given value in the dataset was an AA/CA comparison had little effect, and prostate cancer disparities was significantly associated with population differences in total testosterone, partial r = 0.833, df = 8, p = 0.003, and free testosterone, partial r = 0.666, df = 8, p = 0.035.

In these analyses, population differences in total testosterone consistently showed a stronger relationship than free testosterone with population disparities in prostate cancer incidence. However, a formal test was needed to conclude whether this general trend is statistically meaningful. Using Williams T2 statistic, total testosterone demonstrated a stronger association with prostate cancer disparities than did free testosterone, though this difference was marginally significant, T2 = 1.573, p = 0.077.

Discussion

This meta-analysis used pairwise population comparisons from within a study to account for methodological variability across hormone datasets. Population differences in young men’s total and free testosterone were associated with prostate cancer disparities, and this relationship became stronger for total testosterone after controlling for age, which may reflect the influence of men’s age-related decline in testosterone levels, even among samples of relatively young men. Interestingly, total testosterone demonstrated a more robust association with prostate cancer than did free testosterone. If free testosterone represents the biologically active portion of the molecule, it is puzzling why total testosterone would demonstrate a stronger relationship with prostate cancer risk. It is possible that persistent methodological difficulties in obtaining free testosterone cumulated into more measurement error than was generated by total testosterone assays. However, to the extent that assay procedures with recognized problems were identified and eliminated from analyses, then paying closer attention to the underlying reproductive physiology may provide further insight.

Testosterone is synthesized by the Leydig cells within the testes, and is secreted from the testes primarily into the spermatic vein where testosterone binds to plasma proteins for transport to target tissues [Matsumoto, 2001]. The precise circulatory pathways by which testosterone is delivered throughout the body are not understood completely, but studies on circulatory processes of the male reproductive tract in humans and other mammalian species have demonstrated that: the spermatic vein has the highest concentration of androgens compared with all other points in circulation; the testicular artery has a higher androgen concentration than is found in peripheral circulation because of venous–arterial transfer with spermatic vein blood; and reproductive organs in close anatomical proximity to the testes, including the prostate, have a higher concentration of androgens compared to other body tissues [Nishihara and Suzuki, 1980; Damber et al. 1979; Free, 1977]. Taken together, blood throughout the male reproductive tract is rich in androgenic hormones and accessory sex organs surrounding the testes experience increased hormone exposure.

Recently, a previously unrecognized route of venous flow from the testes to the prostate that bypasses systemic circulation was identified in men with impaired testicular venous drainage (varicocele), and selective occlusion of this circulatory pathway with microsurgery or sclerotherapy substantially reduced prostate exposure to free testosterone [Gat et al. 2009, 2008]. This pathway has not been examined in men with uncompromised reproductive vasculature, but if direct venous flow between the testes and prostate exists to some degree in healthy men (although certainly to a lesser extent than men diagnosed with varicocele), androgenic stimulation of the prostate would be much greater than is indicated by free testosterone levels collected from peripheral circulation. Because total testosterone is a cumulative measure of free and bound forms, it may serve as a closer approximation of free testosterone concentration within reproductive tract circulation given that a considerable fraction of protein-bound testosterone collected at periphery would have circulated in free form near the testes.

Acknowledgements

I thank Grażyna Jasieńska, Jane Lancaster, Martin Muller, and Melissa Emery Thompson along with two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions regarding this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Graduate Research Fellowship Program from the National Science Foundation, 2008–2011.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alvarado L.C. (2010) Population differences in the testosterone levels of young men are associated with prostate cancer disparities in older men. Am J Hum Biol 22: 449–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolelli G., Muti P., Micheli A., Sciajno R., Franceschetti F., Krogh V., et al. (1995) Validity for epidemiological studies of long-term cryoconservation of steroid and protein hormones in serum and plasma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 4: 509–513 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boots L.R., Potter S., Potter D., Azziz R. (1998) Measurement of total serum testosterone levels using commercially available kits: high degree of between-kit variability. Fertil Steril 69: 286–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curado M.P., Edwards B., Shin H.R., Storm H., Ferlay J., Heanue M., et al. (eds) (2007) Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Vol. IX, IARC Scientific Publications No. 160, Lyon, IARC [Google Scholar]

- Damber J.-E., Tomic R., Bergman B., Bergh A. (1979) Increased concentration of testosterone in testis artery blood as compared to peripheral venous blood in man. Int J Androl 2: 315–318 [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger B., Sidney S., Cummings S.R., Libanati C., Bikle D.D., Tekawa I.S., et al. (1997) Racial differences in bone density between young adult black and white subjects persist after adjustment for anthropometric, lifestyle, and biochemical differences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82: 429–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman B.J., Feldman D. (2001) The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 1: 34–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Free M.J. (1977) Blood supply to the testis and its role in local exchange and transport of hormones in the male reproductive tract.. In: Johnson A.D., Gomes W.R. (eds) The Testis Vol. 4, Academic Press: New York, 39–84 [Google Scholar]

- Gat Y., Gornish M., Heiblum M., Joshua S. (2008) Reversal of benign prostate hyperplasia by selective occlusion of impaired venous drainage in the male reproductive system: novel mechanism, new treatment. Andrologia 40: 273–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gat Y., Joshua S., Gornish M.G. (2009) Prostate cancer: a newly discovered route for testosterone to reach the prostate: Treatment by super-selective intraprostatic androgen deprivation. Andrologia 5: 305–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönberg H. (2003) Prostate cancer epidemiology. Lancet 361: 859–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing A.W. (2001) Hormones and prostate cancer: what's next? Epidemiol Rev 23: 42–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson J., Ekström L., Inotsume N., Garle M., Lorentzon M., Ohlsson C., et al. (2006) Large differences in testosterone excretion in Korean and Swedish men are strongly associated with a UDP-glucuronosyl transferase 2B17 polymorphism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 687–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasieńska G., Thune I. (2001) Lifestyle, hormones, and risk of breast cancer. BMJ 322: 586–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasieńska G., Thune I., Ellison P.T. (2000) Energetic factors, ovarian steroids and the risk of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev 9: 231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor P., Luttrell B.M., Williams D. (1993) The free androgen index is not valid for adult males. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 45: 325–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehinde E.O., Akanji A.O., Memon A., Bashir A.A., Daar A.S., Al-Awadi K.A., et al. (2006) Prostate cancer risk: The significance of differences in age related changes in serum conjugated and unconjugated steroid hormone concentrations between Arab and Caucasian men. Int Urol Nephrol 38: 33–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J.G., Nakajin S., Ohno S., Warnock A., Florkowski C.M., Elder P.A. (2005) Circulating levels of isoflavones and markers of 5alpha-reductase activity are higher in Japanese compared with New Zealand males: what is the role of circulating steroids in prostate disease? Steroids 70: 974–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lookingbill D.P., Demers L.M., Wang C., Leung A., Rittmaster R.S., Santen R.J. (1991) Clinical and biochemical parameters of androgen action in normal healthy Caucasian versus Chinese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72: 1242–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A.M. (2001) The testis. In: Felig F., Frohman L.A. (eds) Endocrinology and Metabolism 4th , McGraw-Hill Professional: New York, 635–706 [Google Scholar]

- Morley J.E., Patrick P., Perry H.M., III (2002) Evaluation of assays available to measure free testosterone. Metabolism 51: 554–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris P.D., Malkin C.J., Channer K.S., Jones T.H. (2004) A mathematical comparison of techniques to predict biologically available testosterone in a cohort of 1072 men. Eur J Endocrinol 151: 241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara M., Suzuki Y. (1980) Androgen distribution in male rats. Endocrinol Jpn 27: 637–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, B.W. (1971) Mechanism of action of steroid hormones. N Engl J Med 284:370–377. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Platz E.A., Giovannucci E. (2004) The epidemiology of sex steroid hormones and their signaling and metabolic pathways in the etiology of prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 92: 237–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roddam A.W., Allen N.E., Appleby P., Key T.J. (2008) for the Endogenous Hormones and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer: a collaborative analysis of 18 prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 100: 170–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmann S., Nelson W.G., Rifai N., Brown T.R., Dobs A., Kanarek N., et al. (2007) Serum estrogen, but not testosterone, levels differ between black and white men in a nationally representative sample of Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 2519–2525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner W. (2001) An extraordinarily inaccurate assay for free testosterone is still with us. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 2903–2903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner W., Auchus R.J., Azziz R., Sluss P.M., Raff H. (2007) Position statement: Utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an Endocrine Society position statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R.K., Bernstein L., Judd H., Hanisch R., Pike M., Henderson B. (1986) Serum testosterone levels in healthy young black and white men. J Natl Cancer Inst 76: 45–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R.K., Bernstein L., Lobo R.A., Shimizu H., Stanczyk F.Z., Pike M.C., et al. (1992) 5-alpha-reductase activity and risk of prostate cancer among Japanese and US white and black males. Lancet 339: 887–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santner S.J., Albertson B., Zhang G.Y., Zhang G.H., Santulli M., Wang C., et al. (1998) Comparative rates of androgen production and metabolism in Caucasian and Chinese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 2104–2109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEER (2005) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NIH Publication No. 05-4772. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health.

- Steiger J.H. (1980) Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychol Bull 87: 245–251 [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C.J., Cohn B.A., Cirillo P.M., Feldman D., Stanczyk F.Z., Whittemore A.S. (2006) Sex steroid hormones in young manhood and the risk of subsequent prostate cancer: a longitudinal study in African-Americans and Caucasians (United States). Cancer Causes Control 17: 1237–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen A., Verdonck L., Kaufman J.M. (1999) A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84: 3666–3672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E.J. (1959) The comparison of regression variables. J R Statist Soc B 21: 396–399 [Google Scholar]

- Winters S.J., Brufsky A., Weissfeld J., Trump D.L., Dyky M.A., Hadeed V. (2001) Testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, and body composition in young adult African American and Caucasian men. Metabolism 50(10): 1242–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters S.J., Kelley D.E., Goodpaster B. (1998) The analog free testosterone assay: are the results in men clinically useful? Clin Chem 44: 2178–2182 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright N.M., Renault J., Willi S., Veldhuis J.D., Pandey J.P., Gordon L., et al. (1995) Greater secretion of growth hormone in black than in white men: possible factor in greater bone mineral density—a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80: 2291–2297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]