Abstract

Diagnosing premalignant penile lesions from benign penile dermatoses presents a unique challenge. The rarity of these conditions and the low incidence of penile cancer mean that the majority of our knowledge is based on small, non-randomized, retrospective studies. The introduction of specialist penile cancer centres in the UK has resulted in the centralization of expertise and resources, and has furthered our understanding of the biological behaviour and management of this rare malignancy. We review the current trends in the approach to diagnosing and treating various premalignant penile conditions.

Keywords: carcinoma in situ, diagnosis, penile cancer, treatment

Introduction

Premalignant lesions of the penis can be difficult to distinguish from other benign dermatoses and have an uncertain natural history. A tendency for delayed presentation, often with a history of long-term self management, or unsuccessful treatment, can result in progression to an invasive carcinoma, requiring more extensive surgery. Accurate early diagnosis and treatment before invasion provides the best approach to the management of these lesions. This review outlines the common features of premalignant penile lesions.

Several risk factors have been associated with the development of malignant penile lesions. These include the presence of a foreskin, phimosis, poor hygiene, smoking, chronic inflammation and having multiple sexual partners. Infection with human papilloma virus (HPV) is one of the most important and widely studied risk factors in penile cancer development, with HPV DNA found in approximately 50% of all penile squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) [Backes et al. 2009].

Premalignant penile lesions can be broadly divided into those related to HPV infection, and those which are not HPV related but caused by chronic inflammation. HPV-related lesions include Bowen’s disease (BD), erythroplasia of Queyrat (EQ) and Bowenoid papulosis (BP), which are associated with ‘high-risk’ HPV types 16 and 18. Low-risk HPV types 6 and 11 are associated with other premalignant lesions, such as giant condylomata acuminate (GCA), or Buschke–Lowenstein tumours.

Non-HPV-related lesions are primarily linked to genital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS). However, they are also associated with rarer chronic inflammatory conditions such as penile cutaneous horn, leukoplakia, and pseudoepitheliomatous, keratotic micaceous balanitis (PKMB). Unlike HPV-related tumours, progression of these premalignant lesions is largely into keratinizing/verrucous SCCs.

A recent reclassification system based on cell morphology, squamous differentiation and pathogenesis has been suggested [Chaux et al. 2010]. In the new proposed classification system the term penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN) is used to describe all premalignant lesions. It is further subclassified into differentiated PeIN, the subtype most frequently associated with chronic inflammation and not HPV, and three other subtypes (warty, basaloid, and mixed warty–basaloid), which are linked to HPV infection. However, throughout the remainder of this article, the more widely recognized and established terminology will be used (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Nomenclature for premalignant penile lesions.

| HPV related | Non-HPV related |

|---|---|

| Carcinoma in situ (erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen’s disease) | Lichen sclerosus |

| Cutaneous penile horn | |

| Bowenoid papulosis | Leukoplakia |

| Giant condyloma accuminatum (Bushke-Lowenstein tumour) | Pseudoepitheliomatous, keratotic and micaceous balanitis |

| Warty, basiloid, mixed warty/basiloid PeIN | Differentiated PeIN |

PeIN, penile intraepithelial neoplasia.

Premalignant lesions account for approximately 10% of all penile malignancies at first presentation, with the vast majority occurring on the glans [Brown et al. 2005; Trecedor and Lopez Hernandez, 1991]. The risk of malignant transformation is not clearly defined, but has been reported to be up to 30% if left untreated [Wieland et al. 2000; Mikhall, 1980]. The noninvasive nature of premalignant lesions makes them amenable to curative penile preserving therapies. A number of different approaches can be utilized, depending on the size, site and type of lesion.

HPV-related premalignant lesions

Carcinoma in situ

Carcinoma in situ (CIS) is eponymously known as erythroplasia of Queyrat (EQ) and Bowen's Disease (BD). Both are essentially the same histological premalignant condition, differing primarily only in location. Lesions arising from the mucosal surfaces of the genitalia, such as the inner prepuce and glans, are called EQ, while BD is essentially considered the same pathological process affecting the skin of the penile shaft.

In BD lesions are usually solitary, well defined, scaly, dull-red plaques, often with areas of crusting. Lesions may also be heavily pigmented, resembling melanoma. Occasionally they may have associated leukoplakic, nodular, or ulcerated changes. They occur primarily on the shaft, but may also be encountered in the inguinal and suprapubic regions.

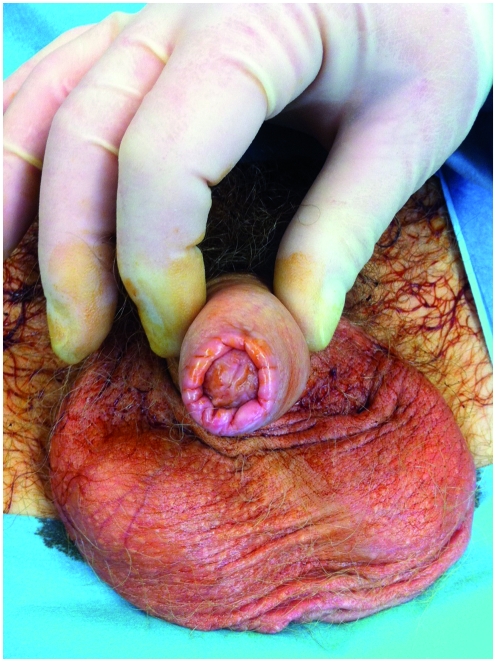

Lesions in EQ are usually sharply defined plaques, which have a smooth, velvety, bright red appearance (Figure 1). They are usually painless, but can have areas of erosion. The vast majority occur in uncircumcised men with phimotic foreskins.

Figure 1.

Carcinoma in Situ arising on the glans penis eponymously known as Erythroplasia of Queyrat.

These two entities have differing rates of progression to invasive disease. Malignant transformation has been reported in 5% of cases of BD [Lucia and MiUer, 1992], while EQ has reported transformation rates of up to 30% [Wieland et al. 2000; Mikhall, 1980].

Bowenoid papulosis

BP occurs primarily in young sexually active men in their 30s. It is highly contagious, and contact tracing is important as sexual partners often have evidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [Obalek et al. 1986]. Lesions occur primarily on the penile shaft or mons, although they can also occasionally arise on the glans and prepuce. They are usually multiple, red, velvety, maculopapular areas, which can coalesce to form larger plaques (Figure 2). Associated pigmentation leads to a brownish appearance, and they often cause pruritis or discomfort. Like EQ and BD, BP is commonly associated with HPV 16. However, unlike the severe dysplasia of CIS, the moderate dysplasia of BP usually runs a more benign course, with malignant transformation in less than 1% of cases, primarily in immunocompromised patients [von Krogh and Horenblas, 2000].

Figure 2.

Bowenoid Papulosis of the penile shaft.

Giant condyloma accuminatum (Bushke-Lowenstein tumour)

Condyloma acuminata are warty, exophytic growths which can affect any part of the anogenital region. On the penis, they primarily occur around the coronal sulcus and frenulum, but can also be found as flat lesions on the penile shaft. They can occasionally extend into the anterior urethra, but more proximal urethral extension into the bladder is usually only seen in immunocompromised patients [Rosemberg, 1991]. Confluence of these lesions can lead to the development of large, exophytic growths known as GCA or Bushke–Lowenstein tumours, after the original description of the condition by the authors in 1925 [Buschke and Lowenstein, 1925] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Giant condyloma accuminatum.

Although histologically their appearance is benign, these lesions can behave in a malignant fashion, invading adjacent structures [Gregoire et al. 1995]. GCA is at risk of malignant transformation into invasive SCC, with reported rates between 30% and 56% [Bertram et al. 1995; Chu et al. 1994].

Non-HPV-related premalignant conditions

Genital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus

This is the most important and prevalent non-HPV-related premalignant condition. Also known as balanitis xerotica obliterans, this idiopathic, chronic, progressive inflammatory process is now better defined as the male genital variant of LS. It primarily affects the glans penis and prepuce of uncircumcised men, and in advanced cases it can involve the urethral meatus and anterior urethra. Lesions classically appear as pale, atrophic plaques, which may coalesce and sclerose, causing phimosis and meatal stenosis (Figure 4). It presents most commonly in men in their third and fourth decades.

Figure 4.

Genital lichen sclerosus affecting the foreskin causing phimosis.

LS is a common synchronous finding in patients with penile cancer, with rates of between 28% and 50% in different series [Pietrzak et al. 2006; Powell and Wojnarowska, 1999]. However, whether this represents a premalignant process remains contentious. Barbagli and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the histology of 130 patients with LS and reported premalignant or malignant features in 11 (8.4%) [Barbagli et al. 2006]. In the largest series to date, SCC was found in 2.3% of 522 patients diagnosed with LS [Depasquale et al. 2000]. Nasca and colleagues reported on a series of 86 patients with LS in which SCC was subsequently found in only 5.8% [Nasca et al. 1999]. In all cases epithelial dysplasia and LS were found adjacent to tumour foci, indicating possible histological progression from chronic inflammation to dysplasia and eventually to malignant transformation. Although European guidelines consider LS to be a premalignant condition [Algaba et al. 2002], no consensus has been agreed on how best to follow these patients.

Cutaneous penile horn

This rare exophytic, conical, keratotic mass arises in areas of chronic inflammation. Little is known about its pathogenesis, but longstanding preputial inflammation and phimosis are known to play an important role [Hemandez-Graulau et al. 1988]. They have a risk of malignant transformation into low-grade verrucous or keratinizing SCC, reported in approximately 30% of cases [Solivan et al. 1990].

Leukoplakia

These rare white, verrucous plaques can arise on mucosal surfaces. Genital lesions occur primarily on the glans or prepuce, and can clinically resemble areas of LS. They occur more commonly in patients with diabetes, probably related to recurrent and chronic infection [Mikhall, 1980]. Dysplastic changes have been reported in 10–20% of cases [Lever and Schaumburg-Lever, 1990; Mikhall, 1980].

Pseudoepitheliomatous, keratotic and micaceous balanitis

This rare idiopathic condition, primarily affects elderly, uncircumcised men. The foreskin often becomes phimotic and patients develop a solitary, well circumscribed, hyperkeratotic lesion on the glans with a laminated (micaceous) appearance. Occasionally the lesion may form into a keratotic mass and can behave more like a verrucous carcinoma. The presence of a nodular component raises the possibility of malignant transformation into invasive SCC, although given the rarity of the condition, this risk is difficult to quantify [Gray and Ansell, 1990; Beljaards et al. 1987].

Treatment of premalignant penile lesions

A number of different options and treatment modalities are available for premalignant penile lesions. The choice of treatment should be tailored to the type and site of the lesion, taking into account patient preference and likely compliance with treatment regimes and the need for close follow up with the more minimally invasive techniques (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment options for premalignant penile lesions.

| Treatment options | Lesion type |

|---|---|

| Topical chemotherapy/immunotherapy (5-fluorouracil/imiquimod) | CIS, BP and PKMB |

| Ideally solitary lesion | |

| Immunocompetent patient | |

| Laser (CO2 or Nd:YAG) | CIS, BP, CA |

| Cryotherapy | CIS, BP, CA |

| Photodynamic therapy | CIS |

| Surgical excision: glans resurfacing (partial/total), circumcision, Moh’s micrographic surgery | All lesion types/sizes |

| Solitary lesions affecting <50% glans for PGR |

BP, Bowenoid papulosis; CA, condyloma acuminate; CIS, carcinoma in situ; PKMB, pseudoepitheliomatous, keratotic micaceous balanitis; PGR, partial glans resurfacing.

Topical therapies

Topical chemotherapy with 5% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is the most commonly used first-line treatment. It is most effective in immunocompetent patients with well defined solitary lesions, and has poor efficacy in immunosuppressed patients or those with widespread ‘field changes’ [Porter et al. 2002]. Lesions amenable to treatment with topical therapy include CIS, BP, and PKMB. Topical therapy is not suitable for LS, GCA, or cutaneous horn.

Protocols vary among clinicians on how frequently the 5-FU is applied. It is usually applied topically for between 4 and 6 weeks on alternate days. Patients are advised to apply the cream with or without gloves provided that thorough hand washing is performed following application. All are warned that the treated area often becomes encrusted and inflamed during the treatment period. Additional application of topical steroid can be used if the areas become uncomfortable during the treatment period, but reactive changes may take between 4 and 8 weeks for the areas to heal. Early studies reported sustained response rates approaching 100% at 5 years, although the numbers of patients treated in these studies is small (<10) [Goette et al. 1975].

Non-responders or partial responders can be treated with immunotherapy using topical 5% imiquimod cream for a similar length of time as second-line treatment. Treatment is usually applied for 5 days a week for a period of 4–6 weeks. The frequency of application can be reduced provided that the inflammatory response is maintained. A review of cohort studies and case series has reported a complete response rate of 70% and a partial response rate of 30%. No recurrences were reported after 12 months [Mahto et al. 2010].

Laser therapy

Carbon dioxide (CO2) and neodymium:yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) lasers have been used as first-line therapy with reasonable response rates and good cosmetic and functional results. The CO2 laser has a tissue penetration of 2–2.5 mm and can be used as a scalpel to excise tissue for histological analysis by direct focusing of the beam. Treated areas generally take 3–4 weeks to heal.

The Nd:YAG laser has a tissue penetration of 3–5 mm, but causes tissue coagulation preventing histological diagnosis, and runs a risk of understaging the disease. Larger lesions can be treated using this laser, but ablation sites can take up to 2–3 months to heal. Treatment with either of these lasers is usually well tolerated, with minor complications including minor pain and bleeding at treatment sites [Tietjen and Malek, 1998]. Laser therapy has primarily been used to treat CIS and BP, and is not suitable for LS, large GCA or cutaneous horn.

Laser has a higher retreatment rate and risk of progression compared with other treatment modalities. In one study of 19 patients treated with laser therapy, 26% required successful retreatment for histologically confirmed Tis recurrence after a mean follow up of 32 months, while one patient (5%) progressed to invasive disease [van Bezooijen et al. 2001]. In another study assessing the combined use of both lasers 19% of patients had disease recurrence, with upgrading from the original tumour in 23% of cases [Windahl and Andersson, 2003]. Higher recurrence rates after laser treatment may reflect a tendency to tackle larger lesions with this minimally invasive approach compared with those treated by other topical therapies.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy uses liquid nitrogen or nitrous oxide to generate rapid freeze/slow thaw cycles to achieve temperatures between −20°C and −50°C to cause tissue damage by formation of ice crystals, leading to disruption of cell membranes and cell death. A study of 299 patients with extragenital BD compared cyrotherapy with topical 5-FU and surgical excision. The study showed that there was a greater risk of recurrence after cyrotherapy (13.4%) compared with 5-FU (9%) and surgical excision (5.5%) [Hansen et al. 2008].

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) for premalignant penile lesions is still in its infancy. This technique involves covering the affected region with a topical photosensitizing cream containing chemicals such as delta-5-aminolaevulinic acid for approximately 3 h, which are preferentially taken up and retained by malignant cells. The lesion is then treated by exposure to incoherent light from a PDT lamp, leading to photoselective cell death of sensitized cells. In a study of 10 patients, only 40% had a complete response after a mean follow up of 35 months, but required on average four treatments [Paoli et al. 2006].

Surgical excision

Circumcision forms an essential part of the management of premalignant conditions, not only to remove the lesion if confined solely to the prepuce, but also to prevent persistence of an environment suited to HPV infection, chronic inflammation and progression to invasive disease. Some centres advocate the use of 5% acetic acid applied to the penis for up to 5 minutes to help detect occult areas of CIS using the ‘acetowhite’ reaction and help guide resection [Pietrzak et al. 2004] but this technique is not advocated by all.

All premalignant lesions are suitable for treatment by surgical excision. Primary surgical excision is advocated in patients who have extensive field change, and in those unlikely or unwilling to adhere to strict treatment and surveillance protocols. It also has a role in recurrent disease following other conservative therapies, where repeated topical therapies result in an unsightly scarred and denuded glans that can make clinical monitoring difficult. A total glans resurfacing procedure provides the best surgical approach to treatment, excising the diseased area with an adequate margin followed by split thickness skin graft. This technique was first described by Bracka for the management of severe LS, but has been adapted for Tis/Ta disease [Depasquale et al. 2000].

Technique of Glans resurfacing

The procedure is performed under a general anaesthetic with preoperative antibiotic cover and with the use of a tourniquet. The glans epithelium is marked in quadrants from the meatus to the coronal sulcus. A perimeatal and circumcoronal incision is performed, and the glans epithelium and subepithelial tissue is then excised from the underlying spongiosum, starting from the meatus to the coronal sulcus for each quadrant. A split thickness skin graft, harvested from the thigh with an air dermatome, is used to cover the ‘exposed’ glans. This technique allows preservation of penile length, form and function and combines good oncological control with a good cosmetic appearance. In a series of 10 patients treated with total glans resurfacing no patient had evidence of disease recurrence after a mean follow up of 30 months [Hadway et al. 2006].

Surgery has the additional advantage of being both diagnostic and therapeutic. Whilst completely removing the diseased epithelium, it allows accurate diagnosis and histopathological staging of the entire specimen, and allows greater assurance of adequate clearance margins. In a recent series assessing the use of primary glans resurfacing for CIS, 10 of 25 patients (40%) had evidence of invasive carcinoma on the final pathological specimens despite all 25 patients having had preoperative incisional biopsies confirming evidence of CIS only [Shabbir et al. 2011].

Partial glans resurfacing

Partial glans resurfacing (PGR) has also been used as a primary surgical approach for glanular CIS. This technique involves the same principles as TGR, but is used in cases of solitary, localized foci of CIS affecting less than 50% of the glans. This approach has the advantage of conserving normal glans skin, allowing better preservation of glanular sensation, and achieving a final appearance closer to the original glans. This approach would be more attractive to younger, sexually active men. In a reported series of primary partial and total glans resurfacing, PGR was associated with a very high risk of positive surgical margins (67%). Forty percent of this group required further surgical intervention, and all were still amenable to further penile preserving techniques, with no subsequent increased risk of recurrence or progression [Shabbir et al. 2011].

Mohs’ micrographic surgery

An alternative surgical approach is excision using Mohs’ micrographic surgery. This involves removal of the entire lesion in thin sections, with concurrent histological examination to ensure clear margins microscopically. While this technique allows maximal preservation of normal penile tissue, it is difficult and time consuming, requiring both a surgeon and pathologist trained in the technique to ensure adequate oncological clearance. A recent review of this technique reported a high (32%) recurrence rate [Shindel et al. 2007], and the uptake and use of the technique worldwide has been very limited.

Follow up

The precise follow-up regime after treatment for premalignant penile lesions is unclear. While it will be mostly dependant on the type of lesion and treatment modality used, a logical and standardized protocol for follow up should be employed, especially given the uncertain natural history, the risk of malignant transformation in up to 30% of patients, and the risk of recurrence of up to 30% after certain treatment modalities. Patients should be seen 3 monthly for the first 2 years, reducing to 6 monthly to complete at least 5 years follow up, although lifelong follow up would give a better insight into the natural course of this rare condition.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

References

- Algaba F., Horenblas S., Pizzocaro G., Solsona E., Windahl T. (2002) European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on penile cancer. Eur Urol 42: 199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backes D.M., Kurman R.J., Pimenta J.M., Smith J.S. (2009) Systematic review of human papillomavirus prevalence in invasive penile cancer. Cancer Causes Control 20: 449–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbagli G., Palminteri E., Mirri F., Guazzoni G., Turini D., Lazzeri M. (2006) Penile carcinoma in patients with genital lichen sclerosus: A multicenter survey. J Urol 175: 1359–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beljaards R.C., van Dijk E., Hausman R. (1987) Is pseudoepitheliomatous micaceous and keratotic balanitis synonymous with verrucous carcinoma? Br J Dermatol 117: 641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram P., Treutner K.H., Rubben A., Hauptmann S., Schumpelick V. (1995) Invasive squamous cell carcinoma in giant anorectal condyloma (Buschke Lowenstein tumor). Langenbecks Arch Chir 380: 115–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C.T., Minhas S., Ralph D.J. (2005) Conservative surgery for penile cancer: Subtotal glans excision without grafting. BJU Int 96: 911–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschke A., Lowenstein L. (1925) Uber carcinomahnliche condyloma acuminate des penis (About Carcinoma similar to Condyloma accuminate of the penis). Klin Wochenschr 4: 1726–1728 [Google Scholar]

- Chaux A., Pfannl R., Lloveras B., Alejo M., Clavero O., Lezcano C., et al. (2010) Distinctive association of p16INK4a over-expression with penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN) depicting warty and/or basaloid features: A study of 141 cases evaluating a new nomenclature. Am J Surg Pathol 34: 385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Q.D., Vereridis M.P., Libbey N.P., Wanebo H.J. (1994) Giant condyloma acuminatum (Buschke Lowenstein tumor) of the anorectal and perianal regions. Dis Colon Rectum 37: 950–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depasquale I., Park A.J., Bracka A. (2000) The treatment of balanitis xerotica obliterans. BJU Int 86: 459–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goette D.K., Elgart M., DeVillez R.L. (1975) Erythroplasia of Queyrat treatment with topically applied 5-fluorouracil. JAMA 232: 934–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M.R., Ansell I.D. (1990) Pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperkeratotic and micaceous balanitis: Evidence for regarding it as pre-malignant. Br J Urol 66: 103–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire L., Cubilla A.L., Reuter V.E., Haas G.P., Lancaster W.D. (1995) Preferential association of human papillomavirus with high-grade histologic variants of penile invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 1705–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadway P., Corbishley C.M., Watkin N.A. (2006) Total glans resurfacing for premalignant lesions of the penis: initial outcome data. BJU Int 98: 532–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J.P., Drake A.L., Walling H.W. (2008) Bowen's disease: A four-year retrospective review of epidemiology and treatment at a university center. Dermatol Surg 34: 878–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemandez-Graulau J.M., Fiore A., Cea P., Tucci P., Addonizio J.C. (1988) Multiple penile horns: Case report and review. J Urol 139: 1055–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever W.F., Schaumburg-Lever G. (1990) Histopathology of the skin 5th , JB Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, [Google Scholar]

- Lucia M.S., MiUer G.J. (1992) Histopathology of malignant lesions of the penis. Urol Clin North Am 19: 227–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahto M., Nathan M., O'Mahony C. (2010) More than a decade on: Review of the use of imiquimod in lower anogenital intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J STD AIDS 21: 8–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhall G.R. (1980) Cancers, precancers, and pseudocancers on the male genitalia: A review of clinical appearances, histopathology, and management. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 6: 1027–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasca M.R., Innocenzi D., Micali G. (1999) Penile cancer among patients with genital lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 41: 911–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obalek S., Jablonska S., Beaudenon S., Walczak L., Orth G. (1986) Bowenoid papulosis of the male and female genitalia: Risk of cervical neoplasia. J Am Acad Dermatol 14: 433–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoli J., Ternesten Bratel A., Löwhagen G.B., Stenquist B., Forslund O., Wennberg A.M. (2006) Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: Results of photodynamic therapy. Acta Derm Venereol 86: 418–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak P., Corbishley C., Watkin N. (2004) Organ-sparing surgery for invasive penile cancer: Early follow-up data. BJU Int 94: 1253–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak P., Hadway P., Corbishley C.M., Watkin N.A. (2006) Is the association between balanitis xerotica obliterans and penile carcinoma underestimated? BJU Int 98: 74–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter W.M., Francis N., Hawkins D., Dinneen M., Bunker C.B. (2002) Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: Clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol 147: 1159–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J., Wojnarowska F. (1999) Lichen sclerosus. Lancet 353: 1777–1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosemberg S.K. (1991) Sexually transmitted papillomaviral infection in men: An update. Dermatol Clin 9: 317–331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabbir M., Muneer A., Kalsi J., Shukla C.J., Zacharakis E., Garaffa G., Ralph D., Minhas S. (2011) Glans resurfacing for the treatment for carcinoma in situ of the penis: Surgical technique and outcomes. Eur Urol 59: 142–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindel A.W., Mann M.W., Lev R.Y., Sengelmann R., Petersen J., Hruza G.J., Brandes S.B. (2007) Mohs micrographic surgery for penile cancer: Management and long-term follow up. J Urol 178: 1980–1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solivan G.A., Smith K.J., James W.D. (1990) Cutaneous horn of the penis: Its association with squamous cell carcinoma and HPV- 16 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 23: 969–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietjen D.N., Malek R.S. (1998) Laser therapy of squamous cell dysplasia and carcinoma of the penis. Urology 52: 559–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trecedor J., Lopez Hernandez B. (1991) Human papillomavirus and mucocutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Piel 6: 470–471 [Google Scholar]

- van Bezooijen B.P., Horenblas S., Meinhardt W., Newling D.W. (2001) Laser therapy for carcinoma in situ of the penis. J Urol 166: 1670–1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Krogh G., Horenblas S.N. (2000) Diagnosis and clinical presentation of premalignant lesions of the penis. Scand J Urol Nephrol 34: 201–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland U., Jurk S., Weissenborn S., Krieg T., Pfister H., Ritzkowsky A. (2000) Erythroplasia of Queyrat: Coinfection with cutaneous carcinogenic human papillomavirus type 8 and genital papillomaviruses in a carcinoma in situ. J Invest Dermatol 115: 396–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windahl T., Andersson S.O. (2003) Combined laser treatment for penile carcinoma: Results after long-term follow up. J Urol 169: 2118–2121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]