Abstract

Purpose of review

Despite the availability of effective therapies, adolescents with type 1 diabetes demonstrate poorer adherence to treatment regimens compared with other pediatric age groups. Nonadherence is tightly linked to suboptimal glycemic control, increasing morbidity, and risk for premature mortality. This article will review barriers to adherence and discuss interventions that have shown promise in improving outcomes for this population.

Recent findings

Adolescents face numerous obstacles to adherence, including developmental behaviors, flux in family dynamics, and perceived social pressures, which compound the relative insulin resistance brought on by pubertal physiology. Some successful interventions have relied on encouraging nonjudgmental family support in the daily tasks of blood glucose monitoring and insulin administration. Other interventions overcome these barriers through the use of motivational interviewing and problem-solving techniques, flexibility in dietary recommendations, and extending provider outreach and support with technology.

Summary

Effective interventions build on teens' internal and external supports (family, technology, and internal motivation) in order to simplify their management of diabetes and provide opportunities for the teens to share the burdens of care. Although such strategies help to minimize the demands placed upon teens with diabetes, suboptimal glycemic control will likely persist for the majority of adolescents until technological breakthroughs allow for automated insulin delivery in closed loop systems.

Keywords: adherence, adolescent, motivational interviewing, type 1 diabetes

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is the second most common chronic illness in teenagers, trailing only asthma. The morbidity and premature mortality associated with diabetes is a major source of suffering [1] and medical expenditures, with diabetes affecting approximately 9% of the US population and accounting for US $174 billion in costs annually [2]. Effective therapies are available but require balancing insulin dosing, diet and exercise along with frequent feedback from blood glucose monitoring results. Thus, implementation of and consistent adherence to such a complex and demanding treatment regimen challenges even the most motivated adolescent. The spontaneity and sense of immortality and exceptionalism that are hallmarks of the teen years are counter to effective diabetes management. Nonetheless, increased adherence to diabetes management favorably impacts glycemic control [3••] and, in turn, lower hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels reduce the risk for diabetes complications [1]. In addition to the complexity of treatment and repeated interruptions to a teen's life, adherence is further complicated by the disincentives of painful needlesticks required for blood glucose monitoring and the nuisance of carrying or wearing insulin administration devices. Despite advances in technology that ease insulin delivery with pens or pumps, adherence to diabetes regimens is often problematic for patients of all ages, but most difficult for adolescents [4].

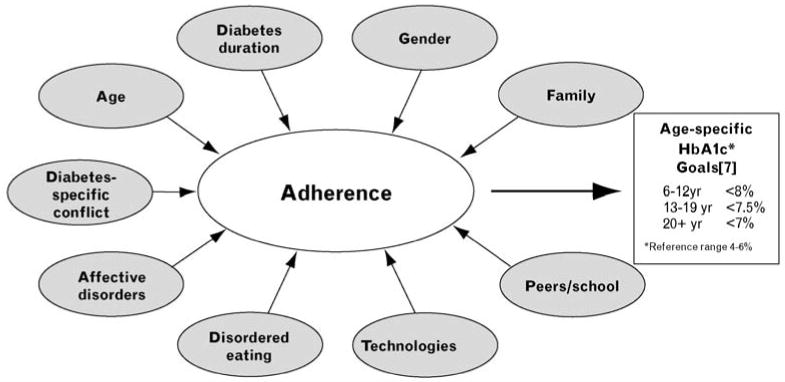

Teens have difficulty achieving and maintaining target glycemic control as a number of factors converge (see Fig. 1). These include heightened concerns about social context and peers, premature shift in responsibility for management from parents to teens, developmental inclination towards risk taking, incomplete knowledge and understanding of treatment regimens and future health risks, fatigue from care of a chronic illness (‘diabetes burnout’), and physiological changes that lead to greater insulin resistance during puberty [5]. In addition, adherence will likely grow more difficult as providers intensify regimens to improve glycemic control for better outcomes with the inadvertent result of increasing burden and reducing health-promoting behaviors [6,7].

Figure 1. Constellation of factors that influence treatment adherence in adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

Although adherence directly influences glycemic control measured as HbA1c, there is a constellation of factors that impacts adherence in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. These include unmodifiable factors such as age and duration of diabetes and modifiable factors such as diabetes-specific family conflict, family involvement, and implementation of technologies for diabetes management. The overall aim is to achieve target glycemic control with HbA1c values of less than 7.5% for teens with diabetes in order to preserve health and prevent long-term complications of the disease. HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

In this review, we will first examine barriers to adolescent adherence and then discuss recent attempts to address these problems through promising work in the field. The unifying themes of successful interventions include persistence, expanding the number of teen supports (professional and family), and ongoing psychoeducational tools to motivate behavior changes in daily life that favor adherence and reduce the daily burdens placed upon teens. These consist mostly of behavioral programs for patients and family members as well as technological innovations, which seek to remind and inspire patients to follow through with their treatment regimens.

Barriers

The following represent a sampling of the obstacles teens face with regard to adherence behaviors.

Peer influences/social context

The data looking at the role of friends on diabetes adherence are mixed. Peer influence may have no impact on adherence [8,9] as well as a positive impact on behaviors such as increased blood sugar monitoring [10] and dietary adherence [11]. Hains et al. [12] found that many adolescents mistakenly believed that friends would have negative reactions to their diabetes, even though empirical work [13] suggests that friends tend to provide encouragement. Recent data from Australia demonstrate a link between anxiety in social situations and poor adherence in boys but not in girls [14•]. Thomas et al. [15] published work looking at differences between children and adolescents with regard to diabetes problem solving and adherence in social situations. These authors found that teens are less adherent due to concerns about fitting in, even though they have increased knowledge about T1D as compared with younger children [15]. Grey et al. [16] studied a form of cognitive behavioral therapy that they called coping skills training (CST) in 12–20-year-olds with T1D who were beginning intensive insulin therapy. The CST intervention included modules on managing situations with friends and conflicts. After 1 year, the authors reported better glycemic control and quality of life among the youth implementing intensive therapy with the addition of CST as compared with intensive therapy alone. Finally, one intriguing study [17•] published last year used momentary sampling to evaluate interpersonal interactions, mood and blood glucose levels, combined with baseline measures of metabolic control, and self-care behaviors. These data showed a link between interpersonal conflict and poor self-care. Taken as a whole, these studies suggest that context can be a barrier for teens and solutions to overcome such barriers need to be individualized. For adolescents seeking privacy, checking blood glucose levels in a nurse's office may suffice, whereas requiring other teens to check glucose levels solely in the nurse's office may intensify concerns about feeling different and isolated.

Affect

Teens with T1D experience depression at rates around 15%, almost twice the rate of unaffected teens [18]. This observation is particularly important in light of studies in which affect and depressed mood have been shown to negatively influence metabolic control in older persons with diabetes [19,20] as well as in teens [21]. McGrady et al. [22•] demonstrated that the association between symptoms of depression and higher HbA1c levels is mediated by diminished adherence to blood glucose monitoring in a study of 276 teens with T1D. Fortenberry et al. [23•] have shown a connection between day-to-day changes in affect and perceived diabetes task competence, whereas previous data in adults with diabetes have yielded connections between stress [24] and strong negative affect [25] with higher blood glucose levels.

Disordered eating

Eating disorders are a common problem in adolescents, with increased rates seen in teens with T1D [26]. This population may be particularly susceptible to disordered eating behaviors as the fundamentals of diabetes management require an intense awareness of food intake, a focus on exercise, unpredictable treatment of hypoglycemia, and a simple yet dangerous means of weight control by insulin restriction. The percentage of women who restrict insulin for weight control varies with age, from 15% among mid-teens to 30% of older teens and adult women. The combination of eating disorders and T1D seems particularly lethal, underscored by recent data that revealed a 3.2-fold increase in mortality after 11 years of follow-up among adult women with T1D who reported restricting insulin at baseline compared with nonrestrictors [27]. Screening for eating disorders in the T1D population can be challenging with standard tools that include questions focused on unusual attention to food intake, which may in fact be viewed as beneficial for teens with diabetes who are appropriately monitoring intake. In addition, standard screening instruments do not account for insulin restriction as a means of purging. New diabetes-specific evaluation tools have been developed for the adolescent population with diabetes [28•].

Interventions

Below are some of the interventions that have been trialed to help teens negotiate their diabetic regimens.

Family involvement

Many studies acknowledge the importance of the family–patient construct. Thus, many behavioral interventions aimed at optimizing adherence and glycemic control in youth with diabetes target the family unit, particularly in younger teens. Successful interventions often result when the teen with diabetes benefits from the understanding, support, and skills of family members in a context that avoids diabetes-specific family conflict. For example, parental diabetes-specific knowledge and problem-solving skills predict HbA1c levels, whereas youth knowledge does not [29]. On the contrary, greater perceived parental burden of diabetes is significantly correlated with higher HbA1c [30]. In order to reduce family burden, Svoren et al. [31] designed and implemented an intervention in which nonmedically trained ‘Care Ambassadors’ facilitated visit follow-up and, in a random subset of families, administered eight psychoeducational modules at regular clinic visits over the 2-year study period. The ‘high-risk’ youth and teen patients and families supported by the Care Ambassadors and receiving the modules experienced a significant decrease in HbA1c and a 40% reduction in hospital admissions and emergency department visits.

The important area of family therapy has been primarily evaluated by two groups. Wysocki et al. [32]'s work with Behavioral Family Systems Therapy for Diabetes (BFST-D) aims to assist parents and adolescents as they work on communication skills, problem solving, and minimizing family conflict in relation to diabetes. A randomized controlled trial of 104 families assigned to either standard care, an attention control group with educational support only, or BFST-D showed significant improvement in the quality of family interactions, family communication, and problem solving with BFST-D. Another series of investigations by Ellis et al. [33] addressed the problem of hospital admissions and nonadherence with multisystemic therapy, an intensive, home-based, family-centered approach offered to patients with poor metabolic control. Although requiring a significant upfront commitment of resources, the program yielded reduced admission rates for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) up to 18 months after cessation of the intervention, leading to a substantial overall saving of healthcare dollars in addition to the medical benefits derived by patients. There is also ongoing investigation to evaluate a family-centered, clinic-based, problem-solving intervention with feasibility data recently published [34•]. As researchers continue to examine ways to optimize adherence and glycemic outcomes in youth with diabetes, it remains important to maintain family support around diabetes management tasks, as the teens of families who sustain parental involvement in diabetes management have better outcomes [35].

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing is predicated on the idea that behavioral change often fails when patients are coerced but succeeds when practitioners work with patients to build discrepancy between their behaviors and aspirations and then support the patients as they contemplate and ultimately make change for their own salient reasons. Motivational interviewing has had promising initial results in short-term, uncontrolled studies in teens [36,37] and has been further examined in a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) from the UK [38]. This study compared teens, aged 14–17 years, who received 12 months of motivational interviewing visits with a control group receiving simply supportive visits for 12 months. Both groups were then followed for an additional year. The mean HbA1c was significantly lower in the motivational interviewing group as compared with the control group at the end of the intervention period, adjusting for baseline values, and this difference was maintained 1 year later. There also were significant differences in anxiety, positive well-being, satisfaction, and belief that self-care mattered in control of diabetes, all favoring the motivational interviewing group.

Many of the previous studies employed trained nursing or mental health professionals as interventionists. Given the shortage of professionals combined with the ubiquity of T1D, alternative approaches using nonprofessional ‘diabetes personal trainers’ may offer benefit [39•]. The ‘trainers’ received 80 h of instruction before using motivational interviewing, problem solving, and behavior analysis principles to guide the delivery of six semistructured in-person sessions supplemented with phone calls over a 2-month intervention period with youth aged 11–16 years with T1D. At 6–12 months following the intervention period, the intervention group had a non-significantly lower mean HbA1c than the control group. However, the intervention yielded a significantly lower HbA1c among the older teens, aged 14–16 years, compared with the older control teens. This observation suggests that there may be a critical time developmentally when teens assume greater responsibility for their diabetes self-management, during which they may be susceptible to the benefits of interventions.

Preventing loss-to-follow-up

Adherence to any treatment regimen is particularly difficult if patients do not come to clinic regularly, and there is a body of literature that documents that the greatest risk for diabetes complications occurs among patients who are lost to follow-up care [40,41]. In addition, studies also validate the opportunities provided by simply facilitating clinic visits. The Care Ambassador program mentioned previously found that a nonmedically trained research assistant who helped families set up appointments, follow-up after missed visits, and address billing concerns increased visit frequency by 50% compared with standard care in which families schedule their own follow-up visits. An Australian study [42] found that it was similarly possible to significantly increase the number of clinic visits, decrease HbA1c, and reduce rates of hospital admissions for DKA by providing assistance with booking appointments similar to the Care Ambassador intervention in addition to offering an after-hours phone support line for the 15–25-year-olds transitioning from pediatric care to care in an adult setting. These modest, cost-effective interventions seem to reduce the amount of hassle teens associate with their diabetes care and, in turn, lead to improved outcomes.

Realistic approaches to eating

Another challenge to adherence is attending to meal planning or ‘counting carbohydrates’ in order to determine proper insulin dosing. Following a recommended diet for diabetes is difficult in general and raises particular challenges for teens, who are often impulsive and likely to engage in eating as a major social event with peers. European clinicians have been working with patients to create less stringent eating regimens, termed ‘normal eating’, and titrating insulin dosages to match such diets [43]. Initially implemented in Germany, the Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE) program was evaluated formally in an RCT in the UK among adults with T1D. The program provides adults with skills training in insulin dose adjustment using a basal-bolus regimen to compensate for less restrictive eating habits. Results revealed lower HbA1c levels and improved general well-being compared with standard care. Knowles et al. [44] and Waller et al. [45] have published their experiences refining [44] and piloting [45] the DAFNE curriculum for 11–16-year-olds with T1D, but we await results from an RCT.

Extending provider reach

Another active area of study has been the use of technology to improve patient and provider communications, to minimize the lag time between identification of problems and subsequent advice, and to reinforce a patient's commitment to behavior change and diabetes self-management. Many technologies are appealing because of the potential to scale-up with minimal cost and manpower, but challenges lie in the rapid rate with which new technologies emerge, are adopted, and then discarded for newer advances. Constant tweaking and innovation may be required to maintain the interest of the adolescent audience with the latest social networking technologies.

Telephone support

Multiple studies [46–48] have examined implementing regular nonphysician phone outreach to teens with diabetes and have yielded mixed results. Data from adults typically demonstrate a modest benefit with regard to HbA1c. However, in teens and children, the majority of studies do not reveal improvements in HbA1c levels, although benefits to intermediate endpoints, such as self-efficacy, are evident. Most studies included calls every 1–3 weeks. However, Lawson et al. [46]'s work in Canada showed a delayed benefit from weekly phone calls in an adolescent population with high HbA1c levels. When a post-hoc analysis was performed 6 months after the intervention, significantly more teens demonstrated improvement and fewer demonstrated deterioration in glycemic control, suggesting that benefits may have accrued in patients with initial poor adherence who may have shifted from precontemplation to contemplation during the telephone intervention period followed by movement to preparation and action after intervention.

Text and e-mail messaging

Investigators have also attempted to engage teens with diabetes with SMS (text) messaging and e-mail. Such interventions offer promise, as teens readily adopt new technologies and the current era offers many relatively low-cost and easily scalable solutions. A sampling of the text messaging studies [49] includes the Sweet Talk trial in Scotland and the Computerized Automated Reminder Diabetes System (CARDS) pilot study [50•] in Boston. The year-long Sweet Talk trial randomized 92 youths and teens with T1D into one of three study groups: conventional therapy, conventional therapy along with Sweet Talk, and intensive insulin therapy along with Sweet Talk. The two Sweet Talk arms received daily text messages, which had personalized prompts, as well as more general messages tailored to the participant's insulin regimen. Although the texting service alone did not produce reductions in HbA1c, it was associated with increases in self-efficacy and self-report of greater adherence. The participants randomized to intensive insulin therapy along with Sweet Talk did experience an almost 1% drop in mean HbA1c levels, viewed as an encouraging result, given that implementation of intensive therapy is resource-intensive and requires additional supports for success [49]. The 3-month pilot CARDS study [50•] randomized 40 teens and young adults with T1D into two groups: one received text message reminders to check blood glucose levels and the other received e-mail reminders. Users of the text message reminder system requested more reminders and responded with more blood glucose results than users of the e-mail reminder system. Although the CARDS system was fully automated and inexpensive to manage, participant interest waned considerably from month 1 to month 3, suggesting that teens and young adults require a highly dynamic and engaging system in order to sustain their interest [50•].

Conclusion

There are many challenges to adherence in adolescents that are intrinsic to their developmental stage and demands for peer normalcy. These impact HbA1c outcomes, as do the physiological factors of adolescent growth and development. Successful interventions for teens tend to be those that diminish the cognitive and emotional barriers of confronting diabetes alone and encourage supportive family involvement in diabetes management devoid of diabetes-specific family conflict. Interventions that streamline services, provide outreach, and motivate behavior change also may benefit teens with T1D. Advances in technology, which rely upon teens to think about their disease and require greater teen input, are unlikely to be effective – the key is creating treatment strategies that can ideally be implemented independent of, or at least with minimal input from, the teen.

This point is evident in data from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) Study Group. This trial compared standard blood glucose monitoring with CGM, a technology in which a subcutaneous sensor relays real-time glucose measurements wirelessly to a receiver. CGM data help to inform insulin dosing and offer warnings when glucose levels stray out of the recommended range into either hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic zones. Three hundred and twenty-two participants of all ages were provided with either CGM equipment or regular glucose monitoring tools in a 26-week RCT. There was a significant improvement in HbA1c without an increase in hypoglycemia among study participants older than 25 years of age, modest improvement in the 8–14-year-old age group, but no improvement in the 15–24-year-old age group [51]. In post-hoc analyses, similar improvements in HbA1c were evident in patients of all ages who used the sensor for 6 or more days per week for the 6-month study. However, teens and young adults aged 15–24 years demonstrated the lowest adherence to sensor use, with only 30% of these patients using the technology 6 or more days per week compared with 86% of patients older than 25 years and 50% of patients aged 8–14 years [52••]. Thus, it seems that the adolescents were simply less willing to accept the demands and personal intrusions of the current generation of CGM technologies despite its promise to improve glycemic control and reduce hypoglycemia.

As evidenced by the adolescents' reluctance to use CGM consistently in the JDRF CGM trial, strategies to increase treatment adherence for teens must require minimal distraction from the teen's routine tasks of daily living. The diabetes clinical and research communities continue to have hope for robust beta-cell replacement therapy or the development of an ‘artificial pancreas’, a device in which continuous glucose measurements determine automatic titration of insulin dosing in real time. However, until these advances are realized, we, as current providers of adolescent care, must continue to think of ways in which we can provide support, ease the burden, and minimize intrusion upon the lives of adolescents with T1D, as we individually tailor their diabetes treatment regimens.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the Leadership Education in Adolescent Health training grant no. T71MC00009 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration. Other supports, K12 DK6369605 and P30DK036836, were from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases; the Charles H. Hood Foundation; the Maria Griffin Drury Pediatric Fund; and the Katherine Adler Astrove Youth Education Fund.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. In 2007. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:596–615. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Hood KK, Peterson CM, Rohan JM, Drotar D. Association between adherence and glycemic control in pediatric type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1171–e1179. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A recent study that demonstrates scope of nonadherence on HbA1c and underscores difficulties in the adolescent population.

- 4.Morris AD, Boyle DI, McMahon AD, et al. Adherence to insulin treatment, glycaemic control, and ketoacidosis in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The DARTS/MEMO Collaboration. Diabetes Audit and Research in Tayside Scotland. Medicines Monitoring Unit. Lancet. 1997;350:1505–1510. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)06234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amiel SA, Sherwin RS, Simonson DC, et al. Impaired insulin action in puberty. A contributing factor to poor glycemic control in adolescents with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:215–219. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607243150402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svoren BM, Volkening LK, Butler DA, et al. Temporal trends in the treatment of pediatric type 1 diabetes and impact on acute outcomes. J Pediatr. 2007;150:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverstein J, Klingensmith G, Copeland K, et al. Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:186–212. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Greca AM, Auslander WF, Greco P, et al. I get by with a little help from my family and friends: adolescents' support for diabetes care. J Pediatr Psychol. 1995;20:449–476. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Escobar O, et al. The role of friendship in the lives of male and female adolescents: does diabetes make a difference? J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bearman KJ, La Greca AM. Assessing friend support of adolescents' diabetes care: the diabetes social support questionnaire-friends version. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:417–428. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.5.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skinner TC, John M, Hampson SE. Social support and personal models of diabetes as predictors of self-care and well being: a longitudinal study of adolescents with diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:257–267. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.4.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hains AA, Berlin KS, Davies WH, et al. Attributions of adolescents with type 1 diabetes in social situations: relationship with expected adherence, diabetes stress, and metabolic control. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:818–822. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.La Greca AM, Bearman KJ, Moore H. Peer relations of youth with pediatric conditions and health risks: promoting social support and healthy lifestyles. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23:271–280. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200208000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Di Battista AM, Hart TA, Greco L, et al. Type 1 diabetes among adolescents: reduced diabetes self-care caused by social fear and fear of hypoglycemia. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35:465–475. doi: 10.1177/0145721709333492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study explores role of peers and highlights teen cognitive processes by discussing the power of short-term embarrassing outcomes to overwhelm long-term treatment goals.

- 15.Thomas AM, Peterson L, Goldstein D. Problem solving and diabetes regimen adherence by children and adolescents with IDDM in social pressure situations: a reflection of normal development. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22:541–561. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grey M, Boland EA, Davidson M, et al. Coping skills training for youth with diabetes mellitus has long-lasting effects on metabolic control and quality of life. J Pediatr. 2000;137:107–113. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.106568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17•.Helgeson VS, Lopez LC, Kamarck T. Peer relationships and diabetes: retrospective and ecological momentary assessment approaches. Health Psychol. 2009;28:273–282. doi: 10.1037/a0013784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; One of a growing number of studies that use momentary sampling techniques to learn about motivations and behaviors in real time as opposed to relying on delayed summative reporting. This study also provides another avenue for insights into adherence.

- 18.Hood KK, Huestis S, Maher A, et al. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: association with diabetes-specific characteristics. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1389–1391. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2154–2160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilbourne AM, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Good CB, et al. How does depression influence diabetes medication adherence in older patients? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:202–210. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grey M, Whittemore R, Tamborlane W. Depression in type 1 diabetes in children: natural history and correlates. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:907–911. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.McGrady ME, Laffel L, Drotar D, et al. Depressive symptoms and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: mediational role of blood glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:804–806. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates the importance of adherence for diabetes outcomes and the impact of psychological well-being on adherence.

- 23•.Fortenberry KT, Butler JM, Butner J, et al. Perceived diabetes task competence mediates the relationship of both negative and positive affect with blood glucose in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study discusses relationship between negative affect and belief in ability to perform regimen behaviors.

- 24.Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, et al. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:934–942. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonder-Frederick LA, Cox DJ, Bobbitt SA, et al. Mood changes associated with blood glucose fluctuations in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Health Psychol. 1989;8:45–59. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.8.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daneman D, Olmstead M, Rydall A, et al. Eating disorders in young women with type 1 diabetes. Prevalence, problems and prevention. Horm Res. 1998;50(Suppl 1):79–86. doi: 10.1159/000053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goebel-Fabbri AE, Fikkan J, Franko DL, et al. Insulin restriction and associated morbidity and mortality in women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:415–419. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28•.Markowitz JT, Butler DA, Volkening LK, et al. Brief screening tool for disordered eating in diabetes: internal consistency and external validity in a contemporary sample of pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:495–500. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides assessment and validation of a measure to screen for disordered eating behaviors specific to diabetics.

- 29.Wysocki T, Ianotti R, Weissberg-Benchell J, et al. Diabetes problem solving by youths with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers: measurement, validation, and longitudinal associations with glycemic control. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:875–884. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butler DA, Zuehlke JB, Tovar A, et al. The impact of modifiable family factors on glycemic control among youth with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9(4 Pt 2):373–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svoren BM, Butler D, Levine BS, et al. Reducing acute adverse outcomes in youths with type 1 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2003;112:914–922. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wysocki T, Harris MA, Buckloh LM, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of Behavioral Family Systems Therapy for Diabetes: maintenance and generalization of effects on parent-adolescent communication. Behav Ther. 2008;39:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellis D, Naar-King S, Templin T, et al. Multisystemic therapy for adolescents with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes: reduced diabetic ketoacidosis admissions and related costs over 24 months. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1746–1747. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34•.Nansel TR, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM, et al. A multisite trial of a clinic-integrated intervention for promoting family management of pediatric type 1 diabetes: feasibility and design. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10:105–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study discusses work on design and implementation of a family-centered problem-solving behavioral intervention.

- 35.Wysocki T, Taylor A, Hough BS, et al. Deviation from developmentally appropriate self-care autonomy. Association with diabetes outcomes. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:119–125. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Channon S, Smith VJ, Gregory JW. A pilot study of motivational interviewing in adolescents with diabetes. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:680–683. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.8.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viner RM, Christie D, Taylor V, Hey S. Motivational/solution-focused intervention improves HbA1c in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a pilot study. Diabet Med. 2003;20:739–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Channon SJ, Huws-Thomas MV, Rollnick S, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing in teenagers with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1390–1395. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39•.Nansel TR, Iannotti RJ, Simons-Morton BG, et al. Long-term maintenance of treatment outcomes: diabetes personal trainer intervention for youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:807–809. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study outlines concepts and results of a clinical trial using nonprofessional ‘trainers’ to implement motivational interviewing techniques aimed at improving outcomes.

- 40.Krolewski AS, Warram JH, Christlieb AR, et al. The changing natural history of nephropathy in type I diabetes. Am J Med. 1985;78:785–794. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobson AM, Hauser ST, Willet J, et al. Consequences of irregular versus continuous medical follow-up in children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 1997;131:727–733. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmes-Walker DJ, Llewellyn AC, Farrell K. A transition care programme which improves diabetes control and reduces hospital admission rates in young adults with Type 1 diabetes aged 15–25 years. Diabet Med. 2007;24:764–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DAFNE Study Group. Training in flexible, intensive insulin management to enable dietary freedom in people with type 1 diabetes: dose adjustment for normal eating (DAFNE) randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325:746. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7367.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knowles J, Waller H, Eiser C, et al. The development of an innovative education curriculum for 11–16 yr old children with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) Pediatr Diabetes. 2006;7:322–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2006.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waller H, Eiser C, Knowles J, et al. Pilot study of a novel educational programme for 11–16 year olds with type 1 diabetes mellitus: the KICk-OFF course. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:927–931. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.132126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawson ML, Cohen N, Richardson C, et al. A randomized trial of regular standardized telephone contact by a diabetes nurse educator in adolescents with poor diabetes control. Pediatr Diabetes. 2005;6:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2005.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nunn E, King B, Smart C, Anderson D. A randomized controlled trial of telephone calls to young patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2006;7:254–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2006.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Howells L, Wilson AC, Skinner TC, et al. A randomized control trial of the effect of negotiated telephone support on glycaemic control in young people with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2002;19:643–648. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franklin VL, Waller A, Pagliari C, Greene SA. A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23:1332–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50•.Hanauer DA, Wentzell K, Laffel N, Laffel LM. Computerized Automated Reminder Diabetes System (CARDS): e-mail and SMS cell phone text messaging reminders to support diabetes management. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11:99–106. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study illustrates the challenges of keeping up with technological advances for this population and the opportunities to improve adherence with text message reminders.

- 51.Tamborlane WV, Beck RW, Bode BW, et al. Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group Continuous glucose monitoring and intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1464–1476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52••.Beck RW, Buckingham B, Miller K, et al. Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group Factors predictive of use and of benefit from continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1947–1953. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Despite the availability of new technologies to enhance diabetes self-management and overcome the physiologic barriers of puberty, major barriers to adherence remain. This study illustrates the challenges of nonadherence in the adolescent population and the need to learn more about motivations for self-care.