Abstract

Background

Interventions to increase physical activity among chronically ill adults are intended to improve quality of life as well as reduce disease complications or slow disease progression.

Objective

This meta-analytic review integrates quality-of-life outcomes from primary research studies testing interventions to increase physical activity among adults with chronic illness.

Methods

Extensive literature searching strategies were employed to locate published and unpublished primary research testing physical activity interventions. Results were coded for studies that had at least 5 participants with chronic illness. Fixed- and random-effects meta-analytic procedures included moderator analyses.

Results

Eighty-five samples from 66 reports with 7,291 subjects were synthesized. The mean quality-of-life effect size for two-group comparisons (treatment vs. control) was 0.11 (higher mean quality-of-life scores for treatment subjects than for control subjects). The treatment group pre-post comparison effect size was 0.27 for quality of life. Heterogeneity was modest in two-group comparisons. Most design and sample attributes were unrelated to intervention effects on quality of life. Studies that exclusively used supervised center-based exercise reported larger quality-of-life improvements than studies that included any educational-motivational content. Effect sizes were larger among unpublished and unfunded studies. The effect size for physical activity did not predict the quality-of-life effect size.

Discussion

Subjects experience improved quality of life from exposure to interventions designed to increase physical activity, despite considerable heterogeneity in the magnitude of the effect. Future primary research should include quality-of-life outcomes so that patterns of relationships among variables can be further explored.

Keywords: quality of life, exercise, chronic disease, meta-analysis, chronic illness, well-being

Most adults with chronic illnesses remain sedentary despite evidence of potential health benefits of increased physical activity (PA). Interventions to increase PA among chronically ill adults are intended to reduce disease complications or slow disease progression as well as improve quality of life (QOL). These potential benefits have contributed to the large body of primary research testing interventions to increase PA. Few previous reviews have addressed QOL outcomes from interventions to increase PA. This quantitative synthesis meets the need to synthesize and integrate the QOL outcome findings to guide practice and inform future research.

Researchers have summarized PA intervention research in numerous narrative reviews and a growing number of meta-analyses. Although reviewers often mention PA’s consequences for QOL, few summarize QOL findings. Instead, reviews address symptoms or health outcomes that are assumed to be related to QOL (Ciccolo, Jowers, & Bartholomew, 2004; Dishman, 2003; Rietberg, Brooks, Uitdehaag, & Kwakkel, 2005). However, neither symptom changes nor health outcomes are adequate proxies for QOL outcomes (Netz, Wu, Becker, & Tenenbaum, 2005). PA may improve QOL beyond symptom and physical function changes (Drewnoski & Evans, 2001; Netz et al. 2005).

Few reviewers have examined QOL outcomes directly. Rejeski, Brawley, and Shumaker’s (1996) narrative review of the link between increased PA and QOL concluded that findings are inconsistent. Some meta-analyses have addressed QOL-related outcomes (e.g. fatigue, depression, anxiety) but have not synthesized outcomes measured by QOL instruments (Devos-Comby, Cronan, & Roesch, 2006; Fox, 2000; Puetz, O’Connor, & Dishman, 2006). The scarce meta-analytic reviews addressing QOL outcomes from PA interventions have been limited to specific diseases or to older adults. They reported mixed outcomes (Netz et al., 2005; Spronk, Bosch, Veen, den Hoed, & Hunink, 2005; Taylor et al., 2005). This meta-analysis was designed to address the need to quantitatively summarize the effects of PA interventions on QOL outcomes in broader participant populations.

This synthesis addressed the following research questions (1) What is the overall mean difference effect size in QOL scores between treatment and control subjects after interventions to increase PA? (2) What is the overall mean difference effect size in QOL scores between treatment subjects prior to versus after PA interventions? (3) Do PA interventions’ effects on QOL outcomes vary depending on characteristics of participants, methodology, or interventions? (4) Do PA behavior outcomes following interventions predict QOL outcomes? (5) For two-group comparisons, do control groups’ post-test outcome measures differ significantly from pre-test values?

Method

Research synthesis methods widely reported in the literature to identify and secure potential primary research reports, evaluate their eligibility, extract data from research reports, meta-analyze primary study characteristics and findings, and interpret meta-analysis results were used. This project is part of a larger study synthesizing PA interventions among chronically ill adults. Further details about methods and results of the findings regarding PA outcomes and disease-specific health outcomes are available in other articles (Conn, Hafdahl, Brown, & Brown, 2008; Conn, Hafdahl, LeMaster et al., 2008; Conn, Hafdahl, Mehr et al. 2007; Conn, Hafdahl, Minor, & Nielsen, 2008; Conn, Hafdahl, Moore, Nielsen, & Brown, 2008; Conn, Hafdahl, Porock, McDaniel, & Nielsen, 2006; Nielsen, Hafdahl, Conn, LeMaster, & Brown, 2006). Several excellent texts are available to readers unfamiliar with meta-analysis methods (Cooper, 1998; Cooper & Hedges, 1994; Lipsey & Wilson, 2001; Sutton, Abrams, Jones, Sheldon, & Song, 2000). The project was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects as not requiring informed consent.

Sample

Diverse search strategies were used to limit the bias introduced by narrow searches (Conn, Isamaralai et al., 2003; Nony, Cucherat, Haugh, & Boissell, 1995). A reference librarian performed computerized searches in 11 databases (MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Dissertation Abstracts International, PsychInfo, SportDiscus, HealthStar, Clinical Evidence, Scopus, DARE, ABI/Inform, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature). Broad search terms were used for intervention (adherence, behavior therapy, clinical trial, compliance, counseling, evaluation, evaluation study, evidence-based medicine, health care evaluation, health behavior, health education, health promotion, intervention, outcome & process assessment, patient education, program, program development, program evaluation, self care, treatment outcome, validation study) and PA (exercise, physical activity, physical fitness, exertion, exercise therapy, physical education & training, walking) (Conn, Isamaralai et al., 2003). The National Institutes of Health database of funded studies was searched. Ancestry searching was conducted on all eligible studies and review articles. Computerized searches were completed on all authors of eligible studies. Conference abstracts were searched. Hand searches of 42 journals with a preponderance of potential primary studies were completed for chronic illness-specific journals (e.g. Diabetologia) and general journals that publish PA research (e.g. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise).

Several strategies were used to search for unpublished studies. Dissertation Abstracts International was thoroughly searched. Conference abstracts were evaluated for eligible studies. Author searches were conducted on both Dissertation Abstracts International and conference abstracts to locate published studies. If published reports were not available, abstract authors were contacted. All first authors of studies included in the meta-analysis were contacted to solicit additional published or unpublished studies. These comprehensive search strategies yielded ten unpublished research reports included in this meta-analysis.

Studies were included that attempted to increase PA behavior by using supervised center-based exercise interventions that measured post-intervention PA, educational-motivational interventions designed to increase PA, or both. Studies with diverse QOL measures were included if adequate data were available to calculate effect sizes (e.g. means and variability measures, exact p value from t test, t statistic). Primary study inclusion criteria are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria for Primary Study Inclusion in Meta-Analysis Management of Data

| Criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Published or unpublished reports | Statistical significance is the most consistent difference between published and unpublished research (Cook et al., 1993; Conn, Valentine, Cooper, & Rantz, 2003). Meta-analyses of only published literature may overestimate ES. |

| Disseminated after 1970 | Few PA studies were conducted with chronically ill adults prior to 1970. Databases rarely include studies prior to 1970. There is little reason to believe QOL outcomes of PA interventions would have changed dramatically between 1970 and 2008. |

| English language studies | Little evidence suggests a language bias in research results. |

| Reported results for at least 5 subjects | A measure of variability requires multiple subjects. Small samples may include difficult-to-recruit subjects or novel interventions. ES weighted so studies with small samples have proportionally less impact on aggregate findings. |

| Diverse research designs acceptable | Diverse design studies more adequately capture extant research than more limited inclusion criteria. Some investigators find it unethical to withhold treatment from any subjects thus do not use true control groups. Randomization may not be possible in some settings (Brown, Upchurch, Anding, Winter, & Ramirez 1996; Dusseldorp, van Elderen, Maes, Meulman, & Kraaij, 19 99). Single-group and two-group data analyzed separately. |

| QOL data coded | Included data from studies that used measured designed to specifically assess QOL. Excluded data from instruments that measures QOL related constructs such as mood. Most distal QOL data available coded since enduring outcomes most important. |

Data Management

Data Abstraction

A coding frame to assess outcomes of primary studies and characteristics of sources, subjects, methods, and interventions was developed, pilot tested, and revised. Coding elements were derived from attributes coded in previous behavior-change meta-analyses, intervention attributes reported in research literature, suggestions from experts in meta-analysis and PA, and findings from the research team’s previous studies. Dissemination vehicle, year of distribution, and presence of funding were coded as source attributes. Participant characteristics included age, gender and minority distribution, and chronic illness inclusion criteria (e.g. diabetes). Attrition, random assignment, and the length of the interval between the intervention and outcome measurement were coded as methodological characteristics. Intervention information including presence or absence of supervised center-based exercise and of educational-motivational sessions, details about any center-based supervised exercise, behavioral target (PA exclusively vs. PA plus other behaviors), intervention intensiveness, social setting, and recommended PA were coded. Other details of interventions were coded but inadequately reported for moderator analyses. PA behavior outcomes were extracted from studies to enable us to examine the association between PA behavior effects and QOL outcomes. For QOL, measures that primary authors described as addressing life satisfaction, well-being, or QOL were coded. To select among multiple measures in some studies, a priori lists of QOL and PA behavior measures with preference given to widely-used and validated instruments determine which outcomes were coded.

Two extensively trained coders extracted the data. Discrepancies in coding were resolved by the senior author or other member of the research team as appropriate. Data coding was not masked because evidence indicates it does not decrease bias. Staff cross checked all author lists to locate research reports that might contain overlapping samples to ensure that only independent samples were analyzed. Authors were contacted to clarify the uniqueness of samples when reports were unclear.

Data Analysis

Table 2 lists important features of the data analyses. A standardized mean difference effect size (ES) for QOL and PA outcomes was calculated. For comparisons between treatment and control groups after the intervention, the ES is the mean of the treatment group minus the mean of the control group, divided by their pooled standard deviation. In two-group comparisons, positive ESs reflect better scores among treatment subjects than control subjects. In single-group studies, positive ESs indicate that subjects scored better after than before the intervention. ESs were weighted such that studies with larger samples had more influence. Homogeneity between studies was assessed with Q. Outliers were examined graphically and statistically. Random-effects analyses were used to estimate the mean and variability of true ESs across studies. (Fixed-effects analyses were also conducted; the report focuses on random-effects results.) The random-effects model is appropriate because heterogeneous studies with varied methods that tested diverse interventions were expected. A Common Language Effect Size (CLES) was calculated to aid interpretation of findings. The ESs could not be converted to an original metric because of the wide variation in QOL measures used and the variation in scoring among studies using the same measure. Moderator analyses were conducted using meta-analytic analogues of ANOVA and regression to determine whether QOL ESs were related to source attributes, methods, intervention characteristics, or PA behavior ESs. Moderator analyses should be considered exploratory given the lack of previous research to suggest hypothesis testing and given the number of studies retrieved. Further information about the analyses is available from the senior author (VC).

Table 2.

Meta-Analytic Management of Data

| Analysis feature | Approach or Rationale |

|---|---|

| Standardized mean difference effect size (ES) (Hedges & Olkin, 1985; Hedges & Vevea, 1998; Morris, 2000; Morris & DeShon, 2002) | Two-group: post-intervention difference between treatment and control means divided by pooled SD. One-group: difference between baseline and outcome means divided by baseline SD. Pre- and post- intervention scores are probably correlated to some extent in single-group design studies. Some measure of the correlation is needed for computing pre-post ES. No studies provided data regarding this association. Lacking empirical evidence, the analyses were conducted under assumptions of no (linear) correlation (ρ12 = 0) and high correlation (ρ12 = .8). Adjusted each ES for bias. Weighted each ES by inverse of within-study sampling variance to address sample size differences. Managed studies with multiple treatment groups & no control as multiple single-group pre-post studies. |

| Outlier identification (Hedges & Olkin, 1985; Lipsey & Wilson, 2001) | Examined ESs graphically. Evaluated externally standardized residuals and homogeneity (Q statistic, variance component) as each ES was removed one at a time. |

| Dependencies in studies with multiple treatment groups compared to single control group (Gleser & Olkin, 1994) | Combined each study’s dependent ESs into single independent ES by generalized least-squares, then used standard univariate random-effects analyses. |

| Random-effect model (Hedges & Olkin, 1985; Raudenbush, 1994) | Assumes observed ESs vary among studies due to both subject-level sampling error & study-level sources of error (Shadish & Haddock, 1994). Consistent with heterogeneous behavioral and educational interventions (Littell, Popa, & Forsyth, 2005). More information about combining heterogeneous studies elsewhere (Conn, Hafdahl, Mehr et al., 2007). Main parameters of interest:

|

| Common Language Effect Size (CLES) (Kline, 2004; McGraw & Wong, 1992) | CLES measures the difference between two populations as the probability that a score sampled from one population would be higher than a score from the other population. Two-group: CLES = Pr(Z < d/SQRT(2)) Pre-post: CLES = Pr(Z < d/SQRT[2(1 - rho)]) The CLES indicates the probability that a random treatment subject would attain better a QOL score than a random control subject, or that a subject would score higher after than before treatment. An ES of 0 (no effect) would have a corresponding CLES of .50. |

| Homogeneity assessment (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001) | Calculated Q statistic as weighted sum of squares that has chi-squared distribution under homogeneity. |

| Publication bias assessment (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001; Vevea & Hedges) | Plotted ES against sampling variance. As sample size increases, sampling error should decrease. Thus smaller studies should scatter more broadly around the mean ES at one end of the plot because they have larger sampling error, while larger studies should cluster more tightly at the other end of the plot since they have smaller sampling error. A symmetrical funnel-shaped plot suggests absence of publication bias. An asymmetrical plot may suggest that some studies with small (or negative) ES were not published. Funnel plots are difficult to assess when few primary studies are available. |

| Moderator analyses (Hedges, 1994; Raudenbush, 1994) | Used mixed- and fixed-effects moderator analyses; fixed- effects results available from senior author. Continuous moderators: Tested effects by z test of unstandardized regression slope (β̂) in meta-analytic analogue of regression. Dichotomous moderators: Tested effects by between- groups heterogeneity statistic (Qbetween) in meta-analytic analogue of ANOVA. Large variance component often increases standard error and decreases statistical power; interpret findings cautiously when significant heterogeneity exists. Findings should be interpreted as exploratory. |

Results

Ultimately 85 samples described in 66 studies in which (approximately) 7,291 subjects participated (a list of included studies is available from the senior author) were included. Ten unpublished research reports were included. The independent group analysis included 5,159 subjects. The pre-post comparison analyses included 4,486 treatment subjects and 3,780 control subjects. The most common chronic illness target populations were cardiac (k = 24), cancer (k = 21), diabetes (k = 19), and arthritis (k = 7). (k represents the number of comparisons.) Table 3 provides descriptive information about the included studies. Sample size ranged from 8 to 927 subjects with small and moderate samples being common (median = 58). Attrition was modest from both treatment and control groups among the studies that reported this information (median = .10). Women were well represented in the samples (median = .56). The median of mean age was 61 years with the youngest sample having a mean age of 40 years and the oldest sample’s mean age was 82 years.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Primary Studies Included in Combined-Illness Quality-of-Life Meta-Analyses

| Characteristic | k | Min | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size per study | 66 | 8 | 21 | 58 | 128 | 927 |

| Proportion of sample assigned to treatment groupa | 35 | .45 | .50 | .53 | .64 | .76 |

| Proportion attrition from treatment group | 52 | .00 | .01 | .10 | .20 | .57 |

| Proportion attrition in comparison groupa | 28 | .00 | .06 | .10 | .18 | .40 |

| Proportion female | 55 | .00 | .28 | .56 | .85 | 1.00 |

| Mean age (years) | 60 | 40 | 53 | 61 | 67 | 82 |

| Minutes supervised exercise per session | 14 | 17 | 33 | 53 | 60 | 75 |

| Total number super. exercise sessions | 25 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 96 |

| Number of weeks over which intervention was delivered | 55 | 1 | 8 | 12 | 21 | 52 |

Note. Includes all studies that contributed at least one independent-groups or pre-post effect size to primary analyses. Independent samples within studies aggregated by summing sample sizes before computing proportions and using weighted mean of other characteristics. k = number of studies providing data on characteristic; Q1 = first quartile, Q3 = third quartile.

Computed for independent-groups studies only.

Eight studies used supervised exercise. Among the studies that used center-based supervised exercise, typical exercise included 36 sessions of nearly 1-hour duration. Fourteen studies included educational or motivational content designed to increase subjects’ PA. Among studies reporting the information, most comparisons (k = 25) use interventions designed to both increase PA and improve other health behaviors while 17 targeted only PA behavior. Most of the studies reporting the social context of the intervention delivered the interventions to groups (k = 28) while others were delivered to individuals (k = 14). Few interventions (k = 8) recommended a specific form of exercise, more did not make such recommendations (k = 34). Interventions duration varied from 1 week to 52 weeks.

Overall Effects of Interventions on Quality-of-Life Outcomes

Table 4 contains results from analyses that address the first, second, and fifth research questions. The paper focuses on random-effects results. The overall mean effect in two-group studies was .11 (μ̂δ in Table 4). The treatment group’s mean pre- versus post-test ES was .27 for both assumptions regarding the pre-post association (see Table 2 for explanation regarding correlation assumptions). Each type of comparison demonstrated significant ES heterogeneity according to the Q homogeneity test, but for two-group studies this was only barely significant and relatively small as quantified by the between-studies variance component’s square root (i.e., the true ESs’ SD), σ̂δ = .071. These findings document that, although interventions’ effects varied somewhat among studies, on average interventions to increase PA improved QOL outcomes, p < 0.001 in every case. In contrast, control subjects experienced little improvement (μ̂δ = .05 – .06), with only the comparison under the high-association assumption being statistically significant at .05 < p < .10.

Table 4.

Independent-Groups Post-test and Single-Group Pre-Post Comparisons on Quality of Life: Random-Effects Point and Interval Estimates and Tests

| ES type | k | Q | μ̂δ | μδ 95% CI | σ̂δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent-groups | 42 | 55.79† | .11*** | (.05, .17) | .071 |

| Treatment pre-post ρ12 = .80 | 71 | 441.88*** | .27*** | (.22, .33) | .195 |

| Treatment pre-post ρ12 = .00 | 71 | 121.09*** | .27*** | (.21, .33) | .156 |

| Comparison pre-post ρ12 = .80 | 25 | 56.29*** | .06* | (.00, .11) | .099 |

| Comparison pre-post, ρ12 = .00 | 25 | 11.92 | .05† | (−.02, .12) | .000 |

Note. Under homogeneity, Q is distributed approximately as chi-square with df = k – 1, where k is the number of (possibly dependent) observed effect sizes; this tests both homogeneity (H0: δ = δi) and the between-studies variance component (H0: ). Weighted method of moments used to estimate . Potential outliers excluded based on random-effects standardized residuals.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001 (for d̄, μ̂δ, and Q).

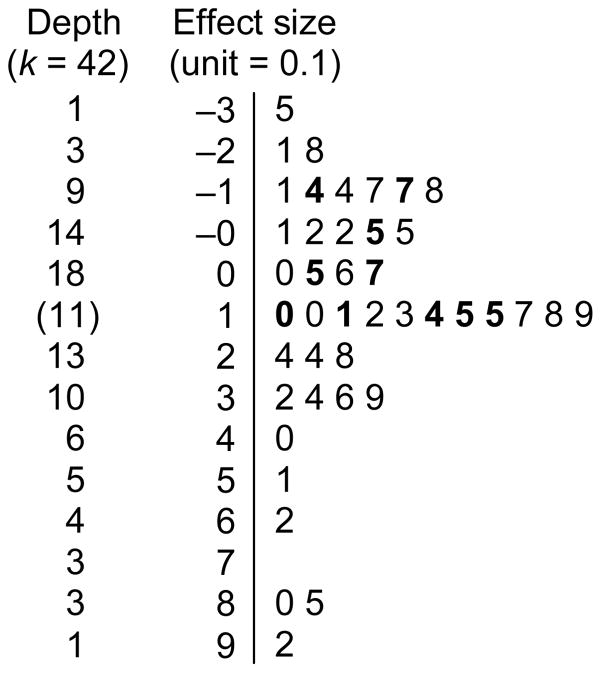

The CLES for the two-group comparisons was .53, indicating that 53% of the time a random treatment subject would have a better QOL value than a random control subject after the intervention (see Table 2 for explanation regarding CLES). The CLES for treatment group pre- and post-intervention comparisons was .58 (assuming no pre-post correlation), indicating that 58% of the time a treatment subject’s QOL score would be better at outcome assessment than at baseline measurement. The CLES for control groups was .51, indicating that control subjects are slightly more likely to have a better outcome QOL score than baseline QOL value. Figure 1 presents a stem-and-leaf display of the 2-group ESs as a visual depiction of findings. The highly diverse measurement of QOL prevented us from converting ES estimates to an original metric. The funnel plots were symmetrical, indicating no obvious evidence of publication bias.

Figure 1.

Stem-and-leaf display of Hedges’s d for 42 independent-groups ESs. Stem unit is 0.1, with ES values rounded; each leaf represents one ES. Boldface leaves are 10 ESs with largest weights (52.4% of total random-effects weight).

Moderator Analysis

Moderator analyses that address the third and fourth research questions are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Dichotomous moderator analyses for two-group comparisons are presented in Table 5. Unpublished studies reported considerably larger mean ESs (μ̂δ = .39) than published studies (μ̂δ = .09). Studies without external funding reported larger mean ESs (μ̂δ = .31) than studies with external funding (μ̂δ = .08). No statistically significant differences were observed between studies that randomly assigned subjects versus those that did not; studies that focused only on PA behavior versus those targeting multiple health behaviors; interventions delivered to individuals versus those given to groups; or studies with specific exercise recommendations (including intensity) versus those without such recommendations. The mean ES difference between studies with center-based supervised exercise (μ̂δ = .16) and studies without supervised exercise (μ̂δ = .06) did not reach statistical significance. Studies that did not use educational-motivational sessions (they used only supervised center-based exercise) reported significantly larger mean ESs (μ̂δ = .24) than studies using only educational-motivational sessions or combined educational-motivational sessions with center-based supervised exercise (μ̂δ = .02).

Table 5.

Independent-Groups Post-test Comparisons on Quality of Life: Dichotomous Moderator Mixed-Effects Analyses

| Moderator | k0 | k1 | QW | μ̂ δ0 | μ̂ δ1 | SEdif | QB | σ̂δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication status | 5 | 37 | 46.5 | .39* | .09** | .156 | 3.7† | .073 |

| Funding | 8 | 34 | 44.6 | .31** | .08* | .101 | 5.4* | .062 |

| Random allocation | 5 | 37 | 48.5 | .22* | .09* | .103 | 1.6 | .084 |

| Days after intervention | 18 | 18 | 37.5 | .07 | .08† | .067 | 0.0 | .061 |

| Supervised exercise | 28 | 14 | 49.0 | .08* | .17** | .073 | 1.5 | .087 |

| Behavioral target | 17 | 25 | 48.6 | .17** | .08* | .076 | 1.5 | .085 |

| Intervention social context | 14 | 28 | 50.7 | .10 | .11** | .073 | 0.0 | .095 |

| Supervise exercise sessions | 28 | 8 | 36.8 | .06† | .16 | .111 | 0.9 | .052 |

| Educ./motivational sessions | 16 | 14 | 33.2 | .24*** | .02 | .083 | 7.1** | .084 |

| Recommend specific exercise | 34 | 8 | 50.3 | .10** | .13 | .094 | 0.1 | .093 |

| Recommend exercise intensity | 3 | 11 | 18.5 | .02 | .19* | .214 | 0.7 | .174 |

Note. kj = number of (possibly dependent) ES estimates in group coded j. Moderator levels: publication status (0 = unpublished, 1 = published); funding (0 = no funding, 1 = some funding), days after intervention (0 = none, 1 = at least 1); behavioral target (0 = physical activity only, 1 = multiple health behaviors); intervention social context (0 = individual, 1 = group); supervised exercise sessions (0 = no center-based supervised sessions, 1 = at least 1); educational/motivational sessions (0 = no educational or motivational sessions, 1 = at least 1); recommended specific exercise (0 = not walking, 1 = walking); recommended intensity (0 = low, 1 = moderate or high); others (0 = absent, 1 = present). Heterogeneity statistics: QB = between groups (distributed as chi-square on df = 1 under H0: δ0 = δ1 or H0:μδ0 = μδ1 ), QW = combined within groups (distributed as chi-square on df = k0 + k1 – 2 under H0: ). Weighted method of moments used to estimate between-studies variance component . Reported if k0≥3 and k1≥3.

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (for QB, QW,μ̂δ0, and μ̂δ1).

Table 6.

Independent-Groups Post-test Comparisons on Quality of Life: Linear Continuous Moderator Mixed-Effects Analyses

| Moderator | k | Qresidual | β̂0 | β̂1 | SE(β̂1) | σ̂δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 40 | 46.7 | −0.108 | 0.004 | 0.0034 | .089 |

| Proportion female | 32 | 39.6 | 0.150 | −0.021 | 0.1354 | .116 |

| Proportion ethnic minority | 6 | 8.1† | 0.492 | −1.165 | 0.9759 | .339 |

| Attrition proportion | 33 | 33.7 | 0.132 | −0.360 | 0.5426 | .055 |

| Days after intervention | 18 | 24.1† | 0.186 | −0.042 | 0.1689 | .129 |

| Supervised exercise contact | 8 | 6.8 | −1.670 | 0.559 | 0.8179 | .114 |

| Educ./motivational contact | 14 | 15.6 | −0.147 | 0.056 | 0.2144 | .090 |

| Recommended min/wk | 11 | 8.2 | 0.357 | −0.001 | 0.0012 | .000 |

| PA two-group d | 29 | 33.1 | 0.125 | 0.039 | 0.1321 | .091 |

| PA pre-post treatment d | 16 | 18.9 | 0.169 | −0.070 | 0.1439 | .108 |

| PA pre-post comparison d | 14 | 14.3 | 0.138 | 0.109 | 0.2364 | .073 |

Note. k = number of (possibly dependent) ES estimates. Moderators: proportion ethnic minority (proportion Black, Hispanic, or Native American); days after intervention (common log of positive days); supervised exercise contact (common log of positive minutes of supervised contact); educational/motivational contact (common log of positive minutes of educational/motivational contact); others are relatively self-explanatory. β̂0 = unstandardized intercept estimate; β̂1= unstandardized slope estimate. Qresidual = residual heterogeneity statistic, beyond that due to moderator (distributed as chi-square on df = k – 2 under H0: , where x is moderator value). Weighted method of moments used to estimate between-studies variance component . Analysis reported if k ≥ 6.

p < .10 (for β̂1 and Qresidual).

Two-group continuous moderator analyses findings are shown in Table 6. Mean QOL ESs were not predicted by participants’ mean age (β̂1 = 0.004); proportion female (β̂1 = −0.021), minority (β̂1 = −1.165), or attrition (β̂1 = −0.360); extent of supervised exercise (β̂1 = 0.559) or educational-motivational contact between interventionists and subjects (β̂1 = 0.056); or PA recommendations (β̂1 = −0.001). In addition, the PA outcome ES was unrelated to QOL outcome ES (PA two-group ES: β̂1 =0.039; PA pre-post treatment group ES: β̂1 = −.070; PA pre-post control group ES: β̂1 = 0.109).

A moderator analysis was conducted to determine if QOL ES differed among the three most common types of chronic illnesses with adequate data (diabetes, cardiac disease, and cancer). The mean QOL ES was .21 for cardiac disease, .15 for cancer, and .04 for diabetes. The results revealed that these differences were not statistically significant (Qbetween = 3.0).

Discussion

This meta-analysis documented that subjects who receive interventions designed to increase their PA experience better QOL outcomes over their baseline scores and in comparison to control subjects. The magnitude of the ES is difficult to assess because too few studies used any single QOL measure in exactly the same way to allow us to convert the ES to an original metric. The ES magnitude, as calculated and as depicted by CLES scores, seems modest. It is unclear what ES would represent a clinically meaningful improvement in QOL among chronically ill adults. People with major chronic illnesses experience many reasons for declining QOL, including the disease itself and physical or psychosocial sequelae of the disease, and onerous or distressing treatments. Studies may recruit chronically ill study subjects from specialty medical practice settings where the subjects may already be receiving optimal medical care. Even a small change in QOL may be important since QOL is a complex phenomenon likely affected by diverse factors.

It is important to note that these findings were heterogeneous, as expected, though less so for two-group than pre-post comparisons and less so for QOL outcomes than for other health and PA outcomes reported in these primary studies (Conn, Hafdahl, Brown et al., 2008; Conn, Hafdahl, Mehr et al., 2007; Conn, Hafdhal, Minor et al., 2008; Conn, Hafdahl, Moore et al. 2008). Interventions varied dramatically from brief motivational sessions to extended supervised exercise programs. Diverse measures were used to assess QOL and PA. No gold standards exist for interventions or measures of QOL and PA. Other important factors that may affect validity of findings which are infrequently reported in primary studies could not be assessed (e.g. treatment fidelity). As more primary research accumulates, future meta-analyses may be able to determine if ES are related to research methods.

The explanation for QOL changes is unclear. These interventions were designed to change PA behavior, not to directly affect QOL. Mean differences in PA behavior were not associated with QOL mean differences in the moderator analyses. It is possible that people achieved small increases in PA that were not detected by the PA measures but that contributed to increased QOL; however, this is inconsistent with the magnitude of ESs on PA in a related study (Conn, Hafdahl, Brown et al., 2008). Even small improvements in functional status from slight increases in PA may contribute to improved QOL. Previous meta-analyses of disease-specific outcomes (e.g. HbA1c, arthritis functional status) among common chronic illnesses documented improved health outcomes (Conn, Hafdahl, Mehr et al., 2007; Conn, Hafdahl, Minor et al., 2008; Conn, Hafdahl, Moore et al., 2008; Nielsen et al., 2006). These improvements may explain the improvements in QOL. It is also possible that subjects experienced enhanced perceived mastery over their chronic illnesses. Future primary PA research should include QOL measures and report the association between improvements in QOL and PA behavior changes to address this issue and avoid possible ecological fallacy in interpreting meta-analytic findings (Berlin, Santanna, Schmid, Szczech & Feldman, 2002). Research syntheses focused on correlates of and explanatory models for QOL could address the association between PA and QOL more directly.

The exploratory moderator analyses documented some intriguing suggestive findings that future research should examine. The larger ES among unpublished and unfunded studies was somewhat surprising. These findings do not support the pattern of publication bias against studies with small ESs often reported in the literature (Cook et al., 1993; Conn, Valentine, Cooper, & Rantz, 2003). These unpublished and unfunded studies may include projects with extraordinary researcher effort to ensure successful projects, such as graduate student research. It is also possible investigators were more likely to provide study information about unpublished studies if the study reported large ESs. The finding of no association between ES and random assignment of subjects does not support the common assumption of bias toward positive effects in studies without random assignment.

Our finding that behavior target (PA behavior only vs. multiple health behavior) was not associated with ES differences contrasts with previous meta-analyses of PA behavior and health outcomes that have documented better outcomes among studies that targeted only PA behavior (Conn, Valentine, & Cooper, 2002; Conn, Hafdahl, Mehr et al., 2007; Conn, Hafdahl, Brown et al., 2008). The meta-analyses that reported larger effects for interventions that focused exclusively on PA behavior have examined outcomes directly affected by PA behavior. The explanation for these differences may become clearer as more intervention trials include QOL outcomes as well as PA behavior and health outcomes.

The absence of moderator effects for age, gender, and minority distribution suggests that diverse samples may experience modest improvement from interventions to increase PA. People with chronic illnesses may avoid changing PA behavior because they fear further decline in their QOL. Many are dealing with demanding chronic illnesses that require continual self-management. Health care providers and health educators may use these exploratory findings to counter fears that increased PA will necessarily decrease QOL.

These findings suggest that interventions using only supervised center-based exercise may have more impact on QOL than interventions including educational-motivational content, regardless of whether it is accompanied by supervised exercise. These findings contrast with previous work documenting a lack of superiority of supervised exercise for PA behavior and health outcomes (Conn, Hafdahl, Mehr et al., 2007). Although the exploratory moderator analyses are intriguing, they should be interpreted with caution. Relationships documented in the moderator analyses may be confounded by other sample- or study-level characteristics. Further primary studies testing differences within randomized controlled trials are needed.

QOL outcomes as measured by well-being, life satisfaction, and QOL measures were included. Studies that used mood, energy, or fatigue measures as QOL outcomes were excluded. Although findings have been mixed, some research has suggested a link between PA and mood (Conn, Hafdahl, Porock et al., 2006; Rietberg et al., 2005) and between PA and energy/fatigue (Puetz, Beasman, & O’Connor, 2006). Few studies in this meta-analysis addressed mood outcomes; after more primary studies reporting mood outcomes have been conducted, a synthesis of mood outcomes would be valuable.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis documented modest improvements in QOL outcomes among adults with chronic illnesses following interventions to increase PA. These findings should encourage researchers and providers evaluating interventions designed to increase PA to include QOL outcome measures in their projects.

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01NR07870) to Vicki Conn, principal investigator.

Contributor Information

Vicki S. Conn, School of Nursing, University of Missouri, Columbia MO.

Adam R. Hafdahl, Washington University, St. Louis MO.

Lori M. Brown, School of Nursing, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO.

References

- Berlin JA, Santanna J, Schmid CH, Szczech LA, Feldman HI Anti-Lymphocyte Antibody Induction Therapy Study . Individual patient- versus group-level data meta-regressions for the investigation of treatment effect modifiers: ecological bias rears its ugly head. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21(3):371–387. doi: 10.1002/sim.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Upchurch S, Anding R, Winter M, Ramirez G. Promoting weight loss in type II diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(6):613–624. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccolo JT, Jowers EM, Bartholomew JB. The benefits of exercise training for quality of life in HIV/AIDS in the post-HAART era. Sports Medicine. 2004;34(8):487–499. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V, Hafdahl A, Brown S, Brown L. Meta-analysis of patient education interventions to increase physical activity among chronically ill adults. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;70:157–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V, Hafdahl A, LeMaster J, Ruppar T, Cochran J, Nielsen P. Interventions to improve self-management among adults with type 1 diabetes: Meta-analysis of metabolic outcomes. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2008;32:315–329. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V, Hafdahl A, Mehr D, LeMaster J, Brown S, Nielsen P. Meta-analysis of metabolic effects of interventions to increase exercise among adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50(5):913–921. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V, Hafdahl A, Minor M, Nielsen P. Physical activity interventions among adults with arthritis: Meta-analysis of outcomes. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatology. 2008;37:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V, Hafdahl A, Moore S, Nielsen P, Brown L. Meta-analysis of interventions to increase physical activity among adults with cardiovascular disease. International Journal of Cardiology. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V, Hafdahl A, Porock D, McDaniel R, Nielsen P. A meta-analysis of exercise interventions among people treated for cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;14(7):699–712. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0905-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V, Isamaralai S, Rath S, Jantarakupt P, Wadhawan R, Dash Y. Beyond MEDLINE for literature searches. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2003;35(2):177–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V, Valentine J, Cooper H. Interventions to increase physical activity among aging adults: a meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24(3):190–200. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn V, Valentine J, Cooper H, Rantz M. Grey literature in meta-analyses. Nursing Research. 2003;52:256–261. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Ryan G, Clifton J, Buckingham L, Willan A, et al. Should unpublished data be included in meta-analyses? Current convictions and controversies. JAMA. 1993;269(21):2749–2753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H. Synthesizing research. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Hedges L. Handbook of research synthesis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Devos-Comby L, Cronan T, Roesch SC. Do exercise and self-management interventions benefit patients with osteoarthritis of the knee? A meta-analytic review. Journal of Rheumatology. 2006;33(4):744–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman RK. The impact of behavior on quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2003;12(Suppl 1):43–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1023517303411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnoski A, Evans W. Nutrition, physical activity, and quality of life in older adults: Summary. Journal of Gerontology. 2001;56A:89–94. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusseldorp E, van Elderen T, Maes S, Meulman J, Kraaij V. A meta-analysis of psychoeduational programs for coronary heart disease patients. Health Psychology. 1999;18(5):506–519. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. The influence of physical activity on mental well-being. Public Health Nutrition. 2000;2:411–418. doi: 10.1017/s1368980099000567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleser LJ, Olkin I. Stochastically dependent effect sizes. In: Cooper H, Hedges L, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L. Fixed effects models. In: Cooper H, Hedges L, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L, Vevea J. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:486–504. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Beyond significance testing: reforming data analysis methods in behavioral research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Littell JH, Popa M, Forsythe B. Multisystemic therapy for social, emotional, and behavioral problems in youth aged 10–17. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(4):CD004797. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004797.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw KO, Wong SP. A common language effect size statistic. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111(2):361–365. [Google Scholar]

- Morris SB. Distribution of the standardized mean change effect size for meta-analysis on repeated measures. British Journal of Mathematical & Statistical Psychology. 2000;53(Pt 1):17–29. doi: 10.1348/000711000159150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):105–125. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netz Y, Wu MJ, Becker BJ, Tenenbaum G. Physical activity and psychological well-being in advanced age: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Psychology & Aging. 2005;20(2):272–284. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen PJ, Hafdahl AR, Conn VS, LeMaster JW, Brown SA. Meta-analysis of the effect of exercise interventions on fitness outcomes among adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2006;74(2):111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nony P, Cucherat M, Haugh MC, Boissel JP. Critical reading of the meta-analysis of clinical trials. Therapie. 1995;50(4):339–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puetz TW, Beasman KM, O’Connor PJ. The effect of cardiac rehabilitation exercise programs on feelings of energy and fatigue: a meta-analysis of research from 1945 to 2005. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. 2006;13(6):886–893. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000230102.55653.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puetz TW, O’Connor PJ, Dishman RK. Effects of chronic exercise on feelings of energy and fatigue: a quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(6):866–876. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S. Random effects models. In: Cooper H, Hedges L, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 301–321. [Google Scholar]

- Rejeski WJ, Brawley LR, Shumaker SA. Physical activity and health-related quality of life. Exercise & Sport Sciences Reviews. 1996;24:71–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietberg MB, Brooks D, Uitdehaag BM, Kwakkel G. Exercise therapy for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;(1):CD003980. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003980.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish W, Haddock C. Combining estimates of effect sizes. In: Cooper H, Hedges L, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 261–282. [Google Scholar]

- Spronk S, Bosch JL, Veen HF, den Hoed PT, Hunink MG. Intermittent claudication: functional capacity and quality of life after exercise training or percutaneous transluminal angioplasty--systematic review. Radiology. 2005;235(3):833–842. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2353040457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton A, Abrams K, Jones D, Sheldon T, Song F. Methods for meta-analysis in medical research. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, Jolliffe J, Noorani H, Rees K, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Medicine. 2004;116(10):682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vevea JL, Hedges LV. A general linear model for estimating effect size in the presence of publication bias. Psychometrika. 1995;60(3):419–435. [Google Scholar]