Abstract

Behavioral and neurophysiological transfer effects from music experience to language processing are well-established but it is currently unclear whether or not linguistic expertise (e.g., speaking a tone language) benefits music-related processing and its perception. Here, we compare brainstem responses of English-speaking musicians/non-musicians and native speakers of Mandarin Chinese elicited by tuned and detuned musical chords, to determine if enhancements in subcortical processing translate to improvements in the perceptual discrimination of musical pitch. Relative to non-musicians, both musicians and Chinese had stronger brainstem representation of the defining pitches of musical sequences. In contrast, two behavioral pitch discrimination tasks revealed that neither Chinese nor non-musicians were able to discriminate subtle changes in musical pitch with the same accuracy as musicians. Pooled across all listeners, brainstem magnitudes predicted behavioral pitch discrimination performance but considering each group individually, only musicians showed connections between neural and behavioral measures. No brain-behavior correlations were found for tone language speakers or non-musicians. These findings point to a dissociation between subcortical neurophysiological processing and behavioral measures of pitch perception in Chinese listeners. We infer that sensory-level enhancement of musical pitch information yields cognitive-level perceptual benefits only when that information is behaviorally relevant to the listener.

Keywords: Pitch discrimination, music perception, tone language, auditory evoked potentials, fundamental frequency-following response (FFR), experience-dependent plasticity

1. INTRODUCTION

Pitch is a ubiquitous parameter of human communication which carries important information in both music and language (Plack, Oxenham, Fay, & Popper, 2005). In music, pitches are selected from fixed hierarchical scales and it is the relative relationships between such scale tones which largely contributes to the sense of a musical key and harmony in tonal music (Krumhansl, 1990). In comparison to music, tone languages provide a unique opportunity for investigating linguistic uses of pitch as these languages exploit variations in pitch at the syllable level to contrast word meaning (Yip, 2002). However, in contrast to music, pitch in language does not contain a hierarchical (i.e., scalar) framework; there is no “in-” or “out-of-tune”. Consequently, the perception of linguistic pitch patterns largely depends on cues related to the specific trajectory (i.e., contour) of pitch movement within a syllable (Gandour, 1983, 1984) rather than distances between consecutive pitches, as it does in music (Dowling, 1978).

It is important to emphasize that linguistic pitch patterns differ substantially from those used in music; lexical tones are continuous and curvilinear (Gandour, 1994; Xu, 2006) whereas in music, pitches unfold in a discrete, stair-stepped manner (Burns, 1999, p. 217; Dowling, 1978). Indeed, specific training or long-term exposure in one domain entrains a listener to utilize pitch cues associated with that domain. Neurophysiological evidence from cortical brain potentials suggests, for instance, that musicians exploit interval based pitch cues (Fujioka, Trainor, Ross, Kakigi, & Pantev, 2004; Krohn, Brattico, Valimaki, & Tervaniemi, 2007) while tone language speakers exploit contour based cues (Chandrasekaran, Gandour, & Krishnan, 2007). Such “cue weighting” is consistent with each group’s unique listening experience and the relative importance of these dimensions to music (Burns & Ward, 1978) and lexical tone perception (Gandour, 1983), respectively. Given these considerable differences, it is unclear a priori, whether pitch experience in one domain would provide benefits in the other domain. That is, whether musical training could enhance language-related pitch processing (music-to-language transfer) or conversely, whether tone language experience could benefit music-related processing (language-to-music transfer).

Yet, a rapidly growing body of evidence suggests that brain mechanisms governing music and language processing interact (Bidelman, Gandour, & Krishnan, 2011; Koelsch et al., 2002; Maess, Koelsch, Gunter, & Friederici, 2001; Patel, 2008; Slevc, Rosenberg, & Patel, 2009). Such cross-domain transfer effects have now been extensively reported in the direction from music to language; musicians demonstrate perceptual enhancements in a myriad of language specific abilities including phonological processing (Anvari, Trainor, Woodside, & Levy, 2002), verbal memory (Chan, Ho, & Cheung, 1998; Franklin et al., 2008), formant and voice pitch discrimination (Bidelman & Krishnan, 2010), sensitivity to prosodic cues (Thompson, Schellenberg, & Husain, 2004), degraded speech perception (Bidelman & Krishnan, 2010; Parbery-Clark, Skoe, Lam, & Kraus, 2009), second language proficiency (Slevc & Miyake, 2006), and lexical tone identification (Delogu, Lampis, & Olivetti Belardinelli, 2006, 2010; Lee & Hung, 2008). These perceptual advantages are corroborated by electrophysiological evidence demonstrating that both cortical (Chandrasekaran, Krishnan, & Gandour, 2009; Marie, Magne, & Besson, 2010; Moreno & Besson, 2005; Pantev, Roberts, Schulz, Engelien, & Ross, 2001; Schon, Magne, & Besson, 2004) and even subcortical (Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011; Musacchia, Strait, & Kraus, 2008; Wong, Skoe, Russo, Dees, & Kraus, 2007) brain circuitry tuned by long-term music experience facilitates the encoding of speech related signals. However, whether or not the reverse effect exists, that is, the ability of language experience to positively influence music processing/perception, remains an unresolved question (e.g., Schellenberg & Peretz, 2008; Schellenberg & Trehub, 2008).

Studies investigating transfer effects in the direction of language-to-music are scarce. Almost all have focused on putative connections between tone language experience and absolute pitch (AP) (e.g., Deutsch, Henthorn, Marvin, & Xu, 2006; Lee & Lee, 2010), i.e., the rare ability to label musical notes without any external reference. It has been noted, however, that AP is largely irrelevant to most music listening (Levitin & Rogers, 2005, p. 26). Musical tasks predominantly involve monitoring the relative relationships between pitches (i.e., intervallic distances) rather than labeling absolute pitch values in isolation. Of language-to-music studies that have focused on intervallic aspects of music, a behavioral study by Pfordresher and Brown (2009) indicated that tone language speakers were better able to discriminate the size (cf. height) of two-tone musical intervals relative to English-speaking non-musicians. In an auditory electrophysiological study, Bidelman et al. (2011) found that brainstem responses evoked by musical intervals were both more accurate and more robust in native speakers of Mandarin Chinese compared to English-speaking non-musicians, suggesting that long-term experience with linguistic pitch may transfer to subcortical encoding of musical pitch. Together, these studies demonstrate a potential for linguistic pitch experience to carry over into nonlinguistic (i.e., musical) domains (Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011, p.430; Pfordresher & Brown, 2009, p.1385). However, to date, no study has investigated concurrently the nature of the relationship between tone language listeners’ neural processing and their behavioral perception of more complex musical stimuli (e.g., chords or arpeggios).

The aim of the present work is to determine the effect of domain-specific pitch experience on the neural processing and perception of musical stimuli. Specifically, we attempt to determine whether the previously observed superiority in Chinese listeners’ subcortical representation of musical pitch (e.g., Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011) provides any benefit in music perception (e.g., Pfordresher & Brown, 2009). We bridge the gap between neurophysiological and behavioral studies of language-to-music transfer effects by examining brainstem responses in conjunction with corresponding perceptual discrimination of complex musical stimuli. We have previously shown that musicians have more robust brainstem representation for defining features of tuned (i.e., major and minor) and detuned chordal arpeggios, and moreover, a superior ability to detect whether they are in or out of tune behaviorally (Bidelman, Krishnan, & Gandour, 2011). By comparing brainstem responses and perceptual discrimination of such chords in Chinese non-musicians versus English-speaking musicians and non-musicians, we are able to assess not only the extent to which linguistic pitch experience enhances preattentive, subcortical encoding of musical chords, but also whether or not such language-dependent neural enhancements confer any behavioral advantages in music perception.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

Eleven English-speaking musicians (M: 7 male, 4 female), 11 English-speaking non-musicians (NM: 6 male, 5 female), and 11 native speakers of Mandarin Chinese (C: 5 male, 6 female) were recruited from the Purdue University student body to participate in the experiment. All participants exhibited normal hearing sensitivity at audiometric frequencies between 500–4000 Hz and reported no previous history of neurological or psychiatric illnesses. They were closely matched in age (M: 22.6 ± 2.2 yrs, NM: 22.8 ± 3.4 yrs, C: 23.7 ± 4.1 yrs), years of formal education (M: 17.1 ± 1.8 yrs, NM: 16.6 ± 2.6 yrs, C: 17.2 ± 2.8 yrs), and were strongly right handed (laterality index > 73%) as measured by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971). Musicians were amateur instrumentalists having ≥ 10 years of continuous instruction on their principal instrument (μ ±σ; 12.4 ± 1.8 yrs), beginning at or before the age of 11 (8.7 ± 1.4 yrs) (Table 1). All currently played his/her instrument(s). Non-musicians had ≤ 1 year of formal music training (0.5 ± 0.5 yrs) on any combination of instruments. No English-speaking participant had any prior experience with a tone language. Chinese participants were born and raised in mainland China. All Chinese subjects were classified as late onset Mandarin/English bilinguals who exhibited moderate proficiency in English, as determined by a language history questionnaire (Ping, Sepanski, & Zhao, 2006). They used their native language in the majority (M = 67%) of their combined daily activities. None had received formal instruction in English before the age of 9 (12.5 ± 2.7 yrs) nor had more than 3 years of musical training (0.8 ± 1.1 yrs). Each participant was paid for his/her time and gave informed consent in compliance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Purdue University.

Table 1.

Musical background of musician participants

| Participant | Instrument(s) | Years of training | Age of onset |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Trumpet/piano | 14 | 10 |

| M2 | Saxophone/piano | 13 | 8 |

| M3 | Piano/guitar | 10 | 9 |

| M4 | Saxophone/clarinet | 13 | 11 |

| M5 | Piano/saxophone | 11 | 8 |

| M6 | Violin/piano | 11 | 8 |

| M7 | Trumpet | 11 | 9 |

| M8 | String bass | 12 | 8 |

| M9 | Trombone/tuba | 11 | 7 |

| M10 | Bassoon/piano | 16 | 7 |

| M11 | Saxophone/piano | 14 | 11 |

|

| |||

| Mean (SD) | 12.4 (1.8) | 8.7 (1.4) | |

2.2 Stimuli

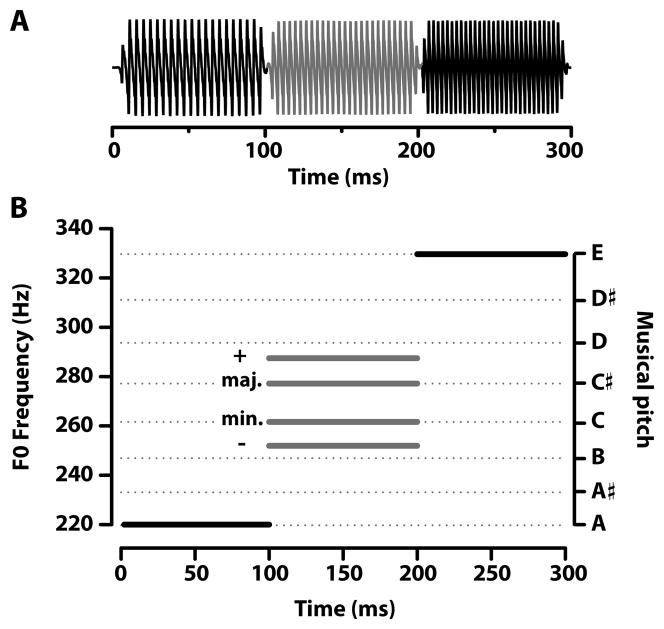

Four triad arpeggios (i.e., three-note chords played sequentially) were constructed which differed only in their chordal third (Fig. 1; Supplemental material). Two sequences were exemplary arpeggios of Western music practice (major and minor); the other two represented detuned versions of these chords (detuned up, +; detuned down, −) whose third was slightly sharp or flat of the actual major or minor third, respectively. Individual notes were synthesized using a tone-complex consisting of 6 harmonics (sine phase) with 100 ms duration (including a 5 ms rise-fall time). For each sequence, the three notes were concatenated to create a contiguous chordal arpeggio 300 ms in duration (Fig. 1A). The fundamental frequency (F0) of each of the three notes (i.e., chordal root, third, fifth) per triad were as follows (Fig. 1B): major = 220, 277, 330 Hz; minor = 220, 262, 330 Hz; detuned up = 220, 287, 330 Hz; detuned down = 220, 252, 330 Hz (Fig. 1B). In the detuned arpeggios, mistuning in the chord’s third represent a +4% or −4% difference in F0 from the actual major or minor third, respectively (cf. a full musical semitone which represents a 6% difference in frequency). Thus, because F0s of the first (root) and third (fifth) notes were identical across stimuli (220 and 330 Hz, respectively) the chords differed only in the F0 of their 2nd note (third).

Figure 1.

Triad arpeggios used to evoke brainstem responses. (A) Four sequences were created by concatenating three 100 ms pitches together (B) whose F0s corresponded to either prototypical (major, minor) or mistuned (detuned up, +; detuned down, −) versions of musical chords. Individual notes were synthesized using a tone-complex consisting of 6 harmonics (amplitudes = 1/N, where N is the harmonic number) added in sine phase. Only the pitch of the chordal third differed between arpeggios as represented by the grayed portion of the time-waveforms (A) and F0 tracks (B). The F0 of the chordal third varied according to the stimulus: major =277 Hz, minor = 262 Hz, detuned up =287 Hz, detuned down = 252 Hz. Detuned thirds represent a 4% difference in F0 from the actual major or minor third, respectively. F0, fundamental frequency.

2.3 Neurophysiological brainstem responses

2.3.1 FFR data acquisition

As a window into the early stages of subcortical pitch processing we utilize the scalp recorded frequency-following response (FFR). The FFR reflects sustained phase-locked activity from a population of neural elements within the rostral midbrain (for review, see Krishnan, 2007) which provides a robust index of the brainstem’s transcription of speech (for reviews, see Johnson, Nicol, & Kraus, 2005; Krishnan & Gandour, 2009; Skoe & Kraus, 2010) and musically relevant features (Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011; Bidelman & Krishnan, 2009, 2011; Bidelman, Krishnan, et al., 2011) of the acoustic signal. The FFR recording protocol was similar to that used in previous reports from our laboratory (e.g., Bidelman & Krishnan, 2009, 2010). Participants reclined comfortably in an acoustically and electrically shielded booth to facilitate recording of brainstem responses. They were instructed to relax and refrain from extraneous body movement (to minimize myogenic artifacts), ignore the sounds they hear, and were allowed to sleep throughout the duration of FFR recording. FFRs were elicited from each participant by monaural stimulation of the right ear at a level of 80 dB SPL through a magnetically shielded insert earphone (ER-3A; Etymotic Research, Elk Grove Village, IL, USA). Each stimulus was presented using rarefaction polarity at a repetition rate of 2.44/s. Presentation order was randomized both within and across participants. Control of the experimental protocol was accomplished by a signal generation and data acquisition system (Intelligent Hearing Systems; Miami, FL, USA).

FFRs were obtained using a vertical electrode montage which provides the optimal configuration for recording brainstem activity (Galbraith et al., 2000). Ag-AgCl scalp electrodes placed on the midline of the forehead at the hairline (~Fz; non-inverting, active) and right mastoid (A2; inverting, reference) served as the inputs to a differential amplifier. Another electrode placed on the mid-forehead (Fpz) served as the common ground. The raw EEG was amplified by 200000 and filtered online between 30–5000 Hz. All inter-electrode impedances were maintained ≤ 1 kΩ. Individual sweeps were recorded using an analysis window of 320 ms at a sampling rate of 10 kHz. Sweeps containing activity exceeding ± 35 μV were rejected as artifacts and excluded from the final average. FFR response waveforms were further band-pass filtered offline from 100 to 2500 Hz (−6 dB/octave roll-off) to minimize low-frequency physiologic noise and limit the inclusion of cortical activity (Musacchia et al., 2008). In total, each FFR response waveform represents the average of 3000 artifact-free stimulus presentations.

2.3.2 FFR data analysis

FFR encoding of information relevant to the pitch of the chord defining note (i.e., the third) was quantified by measuring the magnitude of the F0 component from the corresponding portion of the response waveform per melodic triad. FFRs were segmented into three 100 ms sections (15–115 ms; 115–215 ms; 215–315 ms) corresponding to the sustained portions of the response to each musical note. The spectrum of the second segment, corresponding to the response to the chord’s third, was computed by taking the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of a time-windowed version of its temporal waveform (Gaussian window). For each subject, the magnitude of F0 was measured as the peak in the FFT, relative to the noise floor, which fell in the same frequency range expected by the input stimulus (note 2: 245–300 Hz; see stimulus F0 tracks, Fig. 1B). All FFR data analyses were performed using custom routines coded in MATLAB® 7.10 (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

2.4 Behavioral measures of musical pitch discrimination

2.4.1 F0 discrimination

Behavioral fundamental frequency difference limens (F0 DLs) were measured for each participant in a two-alternative forced choice (2AFC) discrimination task (e.g., Bidelman & Krishnan, 2010; Krishnan, Bidelman, & Gandour, 2010). For a given trial, participants heard two sequential intervals, one containing a reference pitch (i.e., tone complex) and one containing a comparison, assigned randomly. The reference pitch had a fixed F0 frequency of 270 Hz (the average F0 of all chordal stimuli, see Fig. 1); the pitch of the comparison was always greater (i.e., higher F0). The participant’s task was to identify the interval which contained a higher sounding pitch. Following a brief training run, discrimination thresholds were measured using a two-down, one-up adaptive paradigm which tracks the 71% correct point on the psychometric function (Levitt, 1971). Following two consecutive correct responses, the frequency difference of the comparison was decreased for the subsequent trial, and increased following a single incorrect response. Frequency difference between reference and comparison intervals was varied using a geometric step size of between response reversals. Sixteen reversals were measured and the geometric mean of the last 12 taken as the individual’s F0 DL, that is, the minimum frequency difference needed to detect a change in pitch.

2.4.2 Chordal detuning discrimination

Five participants from each group took part in a second pitch discrimination task which was conducted to more closely mimic the FFR protocol and determine whether groups differed in their ability to detect chordal detuning at a perceptual level. Discrimination sensitivity was measured separately for the three most meaningful stimulus pairings (major/minor, major/detuned up, minor/detuned down) using a same-different task (Bidelman, Krishnan, et al., 2011). For each of these three conditions, participants heard 100 pairs of the chordal arpeggios presented with an interstimulus interval of 500 ms. Half of these trials contained chords with different thirds (e.g., major-detuned up) and half were catch trials containing the same chord (e.g., major-major), assigned randomly. After hearing each pair, participants were instructed to judge whether the two chord sequences were the “same” or “different” via a button press on the computer. The number of hits and false alarms were recorded per condition. Hits were defined as “different” responses to a pair of physically different stimuli and false alarms as “different” responses to a pair in which the items were actually identical. All stimuli were presented at ~75 dB SPL through circumaural headphones (Sennheiser HD 580; Sennheiser Electronic Corp., Old Lyme, CT, USA). Stimulus presentation and response collection for both behavioral tasks were implemented in custom interfaces coded in MATLAB.

2.5 Statistical analysis

A two-way, mixed-model ANOVA (SAS®; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was conducted on F0 magnitudes derived from FFRs in order to evaluate the effects of pitch experience (i.e., musical, linguistic, none) and stimulus context (i.e., prototypical vs. non-prototypical sequence) on brainstem encoding of musical pitch. Group (3 levels; musicians, Chinese, non-musicians) functioned as the between-subjects factor and stimulus (4 levels; major, minor, detuned up, detuned down) as the within-subjects factor. An a priori level of significance was set at α = 0.05. All multiple pairwise comparisons were adjusted with Bonferroni corrections. Where appropriate, partial eta-squared (η2p) values are reported to indicate effect sizes.

Behavioral discrimination sensitivity scores (d′) were computed using hit (H) and false alarm (FA) rates (i.e., d′ = z(H)- z(FA), where z(.) represents the z-score operator). Based on initial diagnostics and the Box-Cox procedure (Box & Cox, 1964), both d′ and F0 DL scores were log-transformed to improve normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions necessary for a parametric ANOVA. Log-transformed d′ scores were then submitted to a two-way mixed model with group as the between-subjects factor and stimulus pair (3 levels; major/detuned up, minor/detuned down, major/minor) as the within-subjects factor. Transformed F0 DLs were analyzed using a similar one-way model with group as the between-subjects factor of interest.

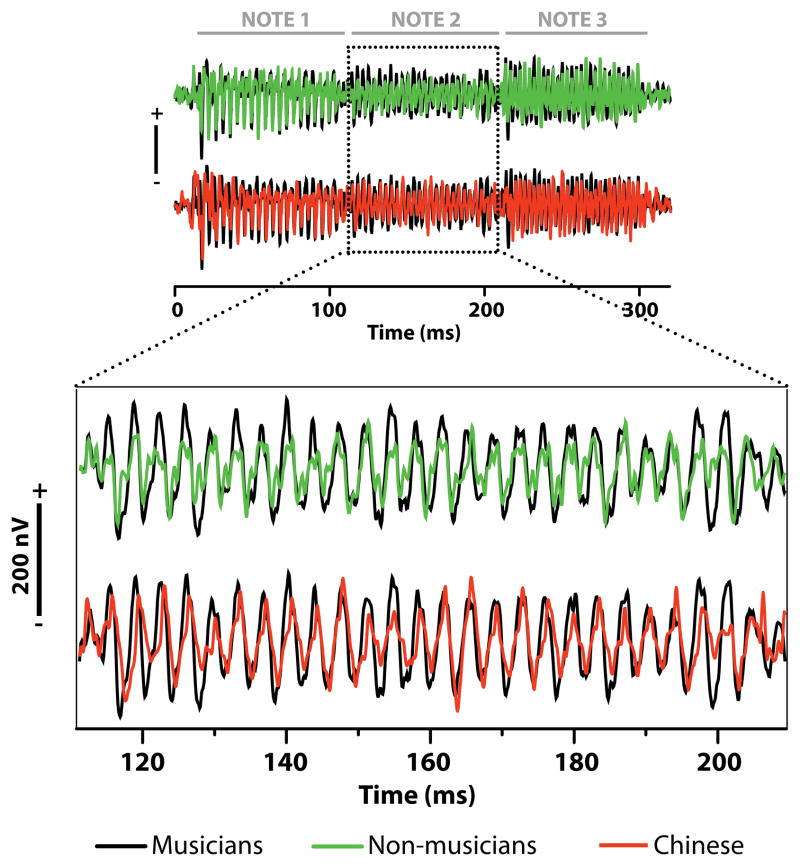

3. RESULTS

FFR time-waveforms in response to the major chord are shown for the three groups in Fig. 2. Similar time-waveforms were observed in response to the other three stimuli. For all groups, clear onset components (i.e., large negative deflections) are seen at the three time marks corresponding to the individual onset of each note (note 1: ~17 ms, note 2: ~ 117 ms, note 3: ~ 217 ms). Relative to non-musicians, musician and Chinese FFRs contain larger amplitudes during the chordal third (2nd note, ~110–210 ms), the defining pitch of the sequence. Within this same time window, non-musician responses show reduced amplitude indicating poorer representation of this chord-defining pitch (see also Fig. 3A).

Figure 2.

Representative FFR time-waveforms evoked by the major triad. To ease group comparisons, Chinese and non-musician responses are overlaid on those of the musician group. As shown by the expanded inset, musicians show larger amplitudes than non-musician listeners during the time window of the chordal third (i.e., 2nd note), the defining pitch of the sequence. Musicians and Chinese show little difference in the same time window. Scale bars = 200 nV.

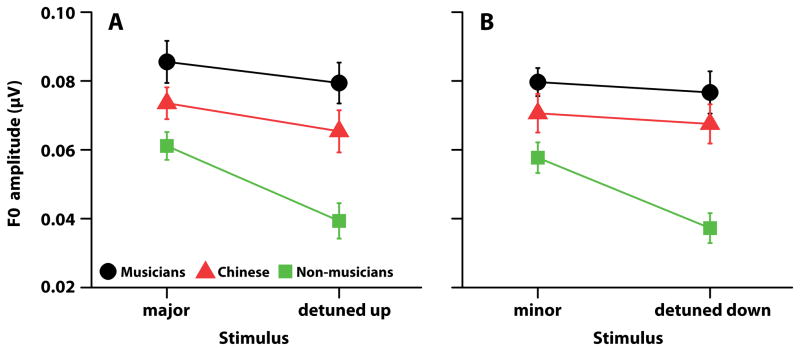

Figure 3.

Group comparisons of brainstem pitch encoding for the defining note of musical triads (i.e., the third). Relative to non-musicians, musicians and Chinese show enhanced F0 magnitudes in response to both prototypical arpeggios and those which are slightly sharp (A) or flat (B) of standard musical chords. Yet, no differences in FFR are found between musicians and Chinese listeners on any of the stimuli. Thus, musical and linguistic pitch experience provides mutual enhancements to brainstem representations of in- and out-of tune musical chords. When the third of the chord is slightly sharp (+4 %) or flat (−4%) relative to the major and minor third, respectively, both musicians and Chinese encode the pitch of detuned notes equally as well as tempered notes (e.g., panel A, compare F0 magnitudes between major and detuned up). Non-musicians, on the other hand, show a marked decrease in F0 magnitude when the chord is detuned from the standard major or minor prototype. Musician and non-musician data are re-plotted from Bidelman et al. (2011). F0, fundamental frequency.

3.1 Neural representation of chordal thirds

FFR encoding of F0 for the thirds of chordal standard and detuned arpeggios are shown in Fig. 3. Individual panels show the meaningful comparisons contrasting a prototypical musical chord with its detuned counterpart: panel A, major vs. detuned up; panel B, minor vs. detuned down. An omnibus ANOVA on F0 encoding revealed significant main effects of group [F2, 30 = 14.01, p < 0.001, η 2p = 0.48] and stimulus [F3, 90= 8.30, p = 0.0001, η 2p = 0.22] on F0 encoding, as well as a group x stimulus interaction [F6, 90 = 2.89, p = 0.0126, η 2p = 0.16].

A priori contrasts revealed that regardless of the eliciting arpeggio, musicians’ brainstem responses contained a larger F0 magnitude than non-musicians. Chinese, on the other hand, had larger F0 magnitudes than non-musicians only for the detuned stimuli. No differences were found between musicians and Chinese for any of the four triads. These group comparisons ([M = C] > NM) indicate that either music or linguistic pitch experience is mutually beneficial to brainstem mechanisms implicated in music processing.

By group, F0 magnitude did not differ across triads for either the musicians or Chinese, indicating superior encoding in both cohorts regardless of whether the chordal third was major or minor, in or out of tune, and irrespective of the listener’s domain of pitch expertise. For non-musicians, F0 encoding was identical between the major and minor chords, two of the most regularly occurring sequences in music (Budge, 1943). However, it was significantly reduced for the detuned up and down sequences in comparison to the major and minor chords, respectively. Together, these results indicate brainstem encoding of musical pitch is impervious to changes in chordal temperament for musicians and Chinese but is diminished with chordal detuning in non-musicians.

3.2 Behavioral measures of musical pitch discrimination

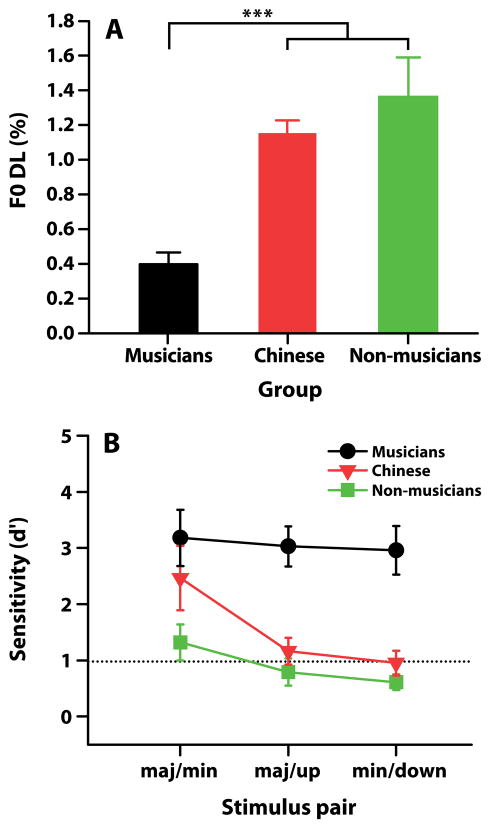

3.2.1 F0 discrimination performance

Mean F0 DLs are shown per group in Fig. 4A. An ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of group on F0 DLs [F2, 30 = 19.90, p < 0.0001, η 2p = 0.57]. Post hoc multiple comparisons revealed that musicians obtained significantly better (i.e., smaller) DLs than musically naïve subjects (M < [C = NM]), meaning that musicians were better able to detect minute changes in absolute pitch. On average, musicians’ DLs were approximately 3–3.5 times smaller than those of the musically untrained subjects (C and NM).

Figure 4.

Perceptual benefits for musical pitch discrimination are limited to musicians. (A) Group comparisons for behavioral frequency difference limens (F0 DLs). Musicians’ pitch discrimination thresholds are ~3 times smaller (i.e., better) than either the English-speaking non-musician or Chinese group, whose performance did not differ from one another. The standard F0 was 270 Hz. (B) Group d′ scores for discriminating chord arpeggios (n = 5 per group). By convention, discrimination threshold is represented by a d′ = 1 (dashed line). Musicians discriminate all chord pairings well above threshold, including standard chords (major/minor) as well as sequences in which the third is out of tune (major/up, minor/down). In contrast, non-musicians and Chinese discriminate only the major/minor pair above threshold. They are unable to accurately distinguish standard from detuned sequences (major/up, minor/down). Musician and non-musician data are re-plotted from Bidelman et al. (2011). Error bars = ±1 SE; ***p < 0.001.

3.2.2 Chordal discrimination performance

Group behavioral chordal discrimination sensitivity, as measured by d′, are shown in Fig. 4B. Values represent one’s ability to discriminate melodic triads where only the third of the chord differed between stimulus pairs. By convention, d′ = 1 (dashed line) represents performance threshold and d′ = 0, chance performance. An ANOVA on d′ scores revealed significant main effects of group [F2, 12 = 13.90, p = 0.0008, η 2p = 0.70] and stimulus pair [F2, 24= 16.21, p < 0.0001, η 2p = 0.57], as well as a group x stimulus pair interaction [F4, 24= 3.92, p = 0.0137, η 2p = 0.40]. By group, a priori contrasts revealed that musicians’ ability to discriminate melodic triads was well above threshold regardless of stimulus pair. No significant differences in their discrimination ability were observed between standard (major/minor) and detuned (major/up, minor/down) stimulus pairs. Chinese and non-musicians, on the other hand, were able to achieve above threshold performance only when discriminating the major/minor pair. They could not accurately distinguish the detuned stimulus pairs (major/up, minor/down). These results indicate that only musicians perceive minute changes in musical pitch, which are otherwise undetectable by musically untrained listeners (C, NM).

By condition, musicians’ ability to discriminate melodic triads was superior to non-musicians across all stimulus pairs. Importantly, musicians were more accurate in discriminating detuned stimulus pairs (major/up, minor/down) than Chinese listeners but did not differ in their major/minor discrimination. No significant differences in chordal discrimination were observed between Chinese and non-musicians.

3.3 Connections between neurophysiological responses to musical pitch

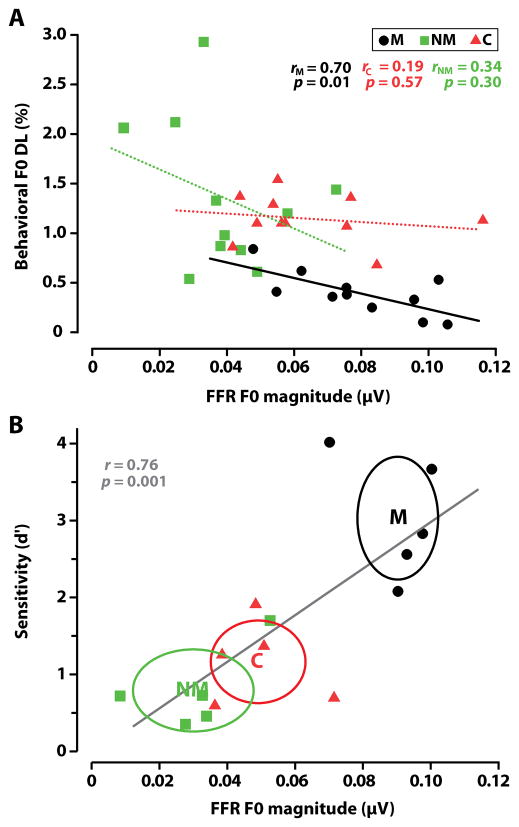

To investigate brain-behavior connections (or lack thereof), we regressed neural (FFR) and behavioral (F0 DL/chordal discrimination) measures against one another to determine the extent to which subcortical responses to detuned musical chords could predict perceptual performance in both behavioral tasks. Note that only n = 5 subjects per group participated in the chordal discrimination task. Pearson’s correlations (r) were computed between brainstem F0 magnitudes elicited in each of the four stimulus conditions and behavioral F0 DLs. Pooled across all listeners, only brainstem responses in the detuned up condition showed close correspondence with F0 DL performance (rall = 0.57, p < 0.001). By group, only musicians revealed a connection between neural and perceptual measures (rM = 0.70, p = 0.01); neither Chinese (rC = 0.19, p = 0.57) nor non-musicians (rNM = 0.34, p = 0.30) exhibited a brain-behavior correlation for this same condition (Fig. 5A). A significant association between these measures in musicians suggests that better pitch discrimination performance (i.e., smaller F0 DLs) is, at least in part, predicted by more robust FFR encoding. The fact that a FFR/F0 DL correlation is found only in musicians indicates that such a brain-behavior connection is limited to musical training and not the result of pitch experience per se (e.g., no correlation is found in the Chinese group).

Figure 5.

(Dis)associations between brainstem encoding and perceptual discrimination of musical pitch. (A) F0 magnitudes computed from brainstem responses to chordal detuning (up condition) predict behavioral discrimination for musicians (rM = 0.70, p = 0.01). That is, better pitch discrimination (i.e., smaller F0 DLs) is predicted by more robust FFR encoding. In contrast to musicians, no correspondence exists between brainstem measures and F0 DLs for Chinese or non-musician listeners (dotted lines, p > 0.05). (B) Across groups, brainstem F0 encoding predicts a listener’s ability to distinguish in and out of tune chords (+4% change in F0), i.e., more robust FFR magnitudes correspond to higher perceptual sensitivity (d′). Each point represents an individual listener’s FFR measure for the detuned up condition plotted against his/her performance in the maj/up discrimination task (n=5 per group). The centroid of each ellipse gives the grand average for each group while its radius denotes ±1 SD in the neural and behavioral dimension, respectively. Note the systematic clustering of groups and musicians’ maximal separation from musically untrained listeners (C and NM) in the neural-perceptual space.

Across groups, brainstem F0 encoding in the detuned up condition also predicted listeners’ performance in discriminating the major chord from its detuned version, as measured by d′ (r = 0.76, p = 0.001; Fig. 5B). Note that a similar correspondence (r = 0.60, p = 0.018) was observed between F0 encoding in the detuned down condition and the corresponding condition in the behavioral task (min/down; data not shown). In this neural-perceptual space, musicians appear maximally separated from musically untrained listeners (Chinese and non-musicians); they have more robust neurophysiological encoding for musical pitch and maintain a higher fidelity (i.e., larger d′) in perceiving minute deviations in chordal arpeggios. The correspondence between FFR encoding for out of tune chords and behavioral detection of such detuning across listeners suggests that an individual’s ability to distinguish pitch deviations in musical sequences is, in part, predicted by how well such auditory features are encoded at a subcortical level.

4. DISCUSSION

By measuring brainstem responses to prototypical and detuned musical chord sequences we found that listeners with extensive pitch experience (musicians and tone-language speakers) have enhanced subcortical representation for musically relevant pitch when compared to inexperienced listeners (English speaking non-musicians). Yet, despite the relatively strong brainstem encoding in the Chinese (neurophysiological language-to-music transfer effect), behavioral measures of pitch discrimination and chordal detuning sensitivity reveal that this neural improvement does not necessarily translate to perceptual benefits as it does in the musician group. Indeed, tone language speakers performed no better than (i.e., as poorly as) English non-musicians in discriminating musical pitch stimuli.

4.1 Cross-domain effects in brainstem encoding of musical chords

Our findings provide further evidence for experience-dependent plasticity induced by long-term experience with pitch. Both musicians and Chinese exhibit stronger pitch encoding of three-note chords as compared to individuals who are untrained musically and lack any exposure to tonal languages (non-musicians) (Figs. 2–3). Their FFRs show no appreciable reduction in neural representation of pitch with parametric manipulation of the chordal third (i.e., major or minor, in or out of tune). These findings demonstrate that sustained brainstem activity is enhanced after long-term experience with pitch regardless of a listener’s specific domain of expertise (i.e., speaking Mandarin vs. playing an instrument). They also converge with previous studies which demonstrate that subcortical pitch processing is not hardwired, but rather, is malleable and depends on an individual’s auditory history and/or training (Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011; Bidelman & Krishnan, 2010; Carcagno & Plack, 2011; Krishnan, Gandour, & Bidelman, 2010; Krishnan, Gandour, Bidelman, & Swaminathan, 2009; Musacchia et al., 2008; Parbery-Clark, Skoe, & Kraus, 2009).

It is possible that the brainstem response enhancements we observe in our “pitch experts” originate as the result of top-down influence. Extensive descending projections from cortex to the inferior colliculus (IC) which comprise the corticofugal pathway are known to modulate/tune response properties in the IC (Suga, 2008), the presumed neural generator of the FFR in humans (Sohmer, Pratt, & Kinarti, 1977). Indeed, animal data indicates that corticofugal feedback strengthens IC response properties as a stimulus becomes behaviorally relevant to the animal through associative learning (Gao & Suga, 1998). Thus, it is plausible that during tone language or music acquisition, corticofugal influence may act to strengthen and hence provide a response “gain” for behaviorally relevant sound (e.g., linguistic tones, musical melodies). Interestingly, this experience-dependent mechanism seems somewhat general in that both tone language and musical experience lead to enhancements in brainstem encoding of pitch, regardless of whether the signal is specific to music or language per se (present study; Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011).

In contrast to musicians and Chinese listeners, brainstem responses of non-musicians are differentially affected by the musical context of arpeggios. This context effect results in diminished magnitudes for detuned chords relative to their major/minor counterparts (Fig. 3). The more favorable encoding of prototypical musical sequences may be likened to the fact that even non-musicians are experienced listeners with the major and minor triads (e.g., Bowling, Gill, Choi, Prinz, & Purves, 2010) which are among the most commonly occurring chords in tonal music (Budge, 1943; Eberlein, 1994). Indeed, based on neural data alone, it would appear prima facie that non-musicians encode only veridical musical pitch relationships and “filter out” detunings. The fact that their neural responses distinguish prototypical from non-prototypical musical arpeggios notwithstanding (Fig. 3), such differentiation appears to play no cognitive role. Non-musicians show the poorest behavioral performance in pitch and chordal discrimination, especially when judging true musical chords from their detuned counterparts (Fig. 4B).

Despite their lack of experience with musical pitch patterns, Chinese non-musicians show superior encoding for chord-defining pitches relative to English-speaking non-musicians. Thus, the neurophysiological benefits afforded by tone language experience extend beyond the bounds of language-specific stimuli. Music-to-language transfer effects are well documented as evidenced by several studies demonstrating enhanced cortical and subcortical linguistic pitch processing in musically trained listeners (e.g., Besson, Schon, Moreno, Santos, & Magne, 2007; Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011; Bidelman & Krishnan, 2010; Marques, Moreno, Castro, & Besson, 2007; Moreno & Besson, 2005; Moreno et al., 2009; Parbery-Clark, Skoe, & Kraus, 2009; Schon et al., 2004; Wong et al., 2007). Our findings provide evidence for the reverse language-to-music transfer effect, i.e., neurophysiological enhancement of musical pitch processing in native speakers of a tone language (cf. Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011; Marie, Kujala, & Besson, 2010). Thus, although the origin of one’s pitch expertise may be exclusively musical or linguistic in nature, years of active listening to complex pitch patterns in and of themselves, regardless of domain, mutually sharpens neural mechanisms recruited for both musical and linguistic pitch processing.

4.2 Behavioral benefits for musical pitch perception are limited to musicians

In contrast to the neurophysiological findings, behaviorally, only musicians achieve superior performance in detecting deviations in pitch and chordal temperament. On average, musicians’ F0 DLs were approximately 3–3.5 times smaller (i.e., better) than those of the musically untrained subjects (i.e., C and NM; Fig. 4A). These data are consistent with previous reports demonstrating superior pitch discrimination thresholds for musicians (Bidelman & Krishnan, 2010; Bidelman, Krishnan, et al., 2011; Kishon-Rabin, Amir, Vexler, & Zaltz, 2001; Micheyl, Delhommeau, Perrot, & Oxenham, 2006; Strait, Kraus, Parbery-Clark, & Ashley, 2010).

Though one may suppose that linguistic pitch experience would enhance a listener’s ability to detect deviations in absolute pitch (e.g., Deutsch et al., 2006), we observe no benefit of tone language experience on F0 DLs (Fig. 4A, C =NM). Our data converge with previous studies which have failed to demonstrate any advantage in absolute pitch sensitivity (i.e., improved JND) for tone language speakers (Bent, Bradlow, & Wright, 2006; Burns & Sampat, 1980; Pfordresher & Brown, 2009; Stagray & Downs, 1993). Prosodic information carried in language depends on pitch contour, direction, and height cues rather than absolute variations in pitch per se (e.g., Gandour, 1983; for review, see Patel, 2008, pp. 46–47). As such, the inability of our Chinese listeners to exploit absolute pitch cues as well as musicians may reflect either the irrelevance of such cues to language or alternatively, the possibility that musical training has a larger impact than linguistic experience on an individual’s perceptual ability to discriminate pitch.

Similarly, in the chordal discrimination task, only musicians are able to discriminate standard and detuned arpeggios well above threshold (Fig. 4B). This finding conflicts with a previous study demonstrating that tone language speakers better discriminate the size (i.e., height) of two-note musical intervals than English-speaking non-musicians (Pfordresher & Brown, 2009). Using three-note musical chords in the present study, non-musicians and Chinese reliably discriminate major from minor chords, in which case the difference between stimuli is a full semitone. However, their discrimination fails to rise above threshold when presented with chords differing by less than a semitone (cf. C and NM on major/minor vs. major/up and minor/down, Fig. 4B). The apparent discrepancy with Pfordresher & Brown (2009) is likely attributable to differences in stimulus complexity and task demands. Whereas their two-note interval stimuli require a simple comparison of pitch height between sets of simultaneously sounding notes (harmonic discrimination), our three-note chordal arpeggios require a listener to monitor the entire triad over time, in addition to comparing the size of its constituent intervals (melodic discrimination). Thus, while tone language speakers may enjoy a perceptual advantage in simple pitch height (cf. intervallic distance) discrimination (Pfordresher & Brown, 2009), this benefit largely disappears when the listener is required to detect subtle changes (i.e., < 1 semitone) within a melodic sequence of pitches. This ability, on the other hand, is a defining characteristic of a musician as reflected by their ceiling performance in discriminating all chordal conditions. Indeed, it may also be the case that the superiority of musicians over tone language speakers we observe for both behavioral tasks is linked to differences in auditory working memory and attention which are typically heightened in musically trained individuals (Pallesen et al., 2010; Parbery-Clark, Skoe, Lam, et al., 2009; Strait et al., 2010).

4.3 Dissociation between neural and perceptual representations of musical pitch

Our findings point to a dissociation between neural encoding of musical pitch and behavioral measures of pitch perception in tone language speakers (Fig. 5). Tone language experience may enhance brain mechanisms that subserve pitch processing in music as well as language. These mechanisms nevertheless may support distinct representations of pitch (Pfordresher & Brown, 2009, p. 1396). We demonstrate herein that enhanced brainstem representation of musical pitch notwithstanding (Fig. 3), it fails to translate into perceptual benefits for tone language speakers as it does for musicians (Figs. 4–5). It is plausible that dedicated brain circuitry exists to mediate musical percepts (e.g., Peretz, 2001) which may be differentially activated or highly developed dependent upon one’s musical training (Foster & Zatorre, 2010; Pantev et al., 1998; Zarate & Zatorre, 2008). During pitch memory tasks, for example, non-musicians primarily recruit sensory cortices (primary/secondary auditory areas), while musicians show additional activation in the right supramarginal gyrus and superior parietal lobule, regions implicated in auditory short-term memory and pitch recall (Gaab & Schlaug, 2003). These results highlight the fact that similar neuronal networks are differentially recruited and tuned dependent on musical experience even under the same task demands.

Whether or not robust representations observed in subcortical responses engage such cortical circuitry may depend on the cognitive relevance of the stimulus to the listener (Abrams et al., 2010; Bidelman, Krishnan, et al., 2011; Chandrasekaran et al., 2009; Halpern, Martin, & Reed, 2008). Thus, in tone language speakers, it might be the case that information relayed from the brainstem fails to differentially engage these higher-level cortical mechanisms which subserve the perception and cognition of musical pitch, as it does for musicians. Indeed, we find no association between neurophysiological and behavioral measures in either group lacking musical training (C and NM) in contrast to the strong correlations between brain and behavior for musically trained listeners (Fig. 5). Our results, however, do not preclude the possibility that the brain-behavior dissociation observed in the Chinese group can be minimized or even eliminated with learning or training. That is, the neural enhancements we find in Chinese non-musicians, relative to English-speaking non-musicians (Fig. 3), could act to facilitate/accelerate improvements in their ability to discriminate musical pitch with active training.

As in language, brain networks engaged during music probably involve a series of computations applied to the neural representation at different stages of processing (Hickok & Poeppel, 2004; Poeppel, Idsardi, & van Wassenhove, 2008). Sensory information is continuously pruned and transformed along the auditory pathway dependent upon its functional role, e.g., whether or not it is linguistically- (Krishnan et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2006) or musically-relevant (Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011; Bidelman, Krishnan, et al., 2011) to the listener. Eventually, this information reaches complex cortical circuitry responsible for encoding/decoding musical percepts including melody and harmony (Koelsch & Jentschke, 2010) and the discrimination of pitch (Brattico et al., 2009; Koelsch, Schroger, & Tervaniemi, 1999; Tervaniemi, Just, Koelsch, Widmann, & Schroger, 2005). Yet, whether these encoded features are utilized effectively and retrieved during perceptual music tasks depends on the context and functional relevance of the sound, the degree of the listener’s expertise, and the attentional demands of the task (Tervaniemi et al., 2005; Tervaniemi et al., 2009).

5. CONCLUSION

The presence of cross-domain transfer effects at pre-attentive stages of auditory processing does not necessarily imply that such effects will transfer to cognitive stages of processing invoked during music perception. Enhanced neural representation for pitch alone, while presumably necessary, is insufficient to produce perceptual benefits for music listening. We infer that neurophysiological enhancements are utilized by cognitive mechanisms only when the particular demands of an auditory environment coincide with one’s long-term experience (Bidelman, Gandour, et al., 2011; Tervaniemi et al., 2009). Indeed, our data show that while both extensive music and language experience enhance neural representations for musical stimuli, only musicians truly make use of this information at a perceptual level.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS.

Pitch experience (Musicians & Chinese) strengthens subcortical encoding of musical sequences.

Musicians are superior to Chinese & non-musicians in pitch discrimination tasks.

Dissociation between neural & perceptual measures of music processing in Chinese listeners.

Sensory enhancements → cognitive benefits when a signal is behaviorally relevant.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on part of a doctoral dissertation by the first author submitted to Purdue University in May 2011. Research supported in part by NIH R01 DC008549 (A.K.), NIDCD T32 DC00030 (G.B.), and Purdue University Bilsland dissertation fellowship (G.B.).

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- C

Chinese

- DL

difference limen

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- F0

fundamental frequency

- FFR

frequency-following response

- FFT

Fast Fourier Transform

- M

musicians

- NM

non-musicians

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrams DA, Bhatara A, Ryali S, Balaban E, Levitin DJ, Menon V. Decoding temporal structure in music and speech relies on shared brain resources but elicits different fine-scale spatial patterns. Cerebral Cortex. 2010 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anvari SH, Trainor LJ, Woodside J, Levy BA. Relations among musical skills, phonological processing and early reading ability in preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2002;83(2):111–130. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0965(02)00124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent T, Bradlow AR, Wright BA. The influence of linguistic experience on the cognitive processing of pitch in speech and nonspeech sounds. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2006;32(1):97–103. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.32.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson M, Schon D, Moreno S, Santos A, Magne C. Influence of musical expertise and musical training on pitch processing in music and language. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 2007;25(3–4):399–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidelman GM, Gandour JT, Krishnan A. Cross-domain effects of music and language experience on the representation of pitch in the human auditory brainstem. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23(2):425–434. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidelman GM, Krishnan A. Neural correlates of consonance, dissonance, and the hierarchy of musical pitch in the human brainstem. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(42):13165–13171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3900-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidelman GM, Krishnan A. Effects of reverberation on brainstem representation of speech in musicians and non-musicians. Brain Research. 2010;1355:112–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidelman GM, Krishnan A. Brainstem correlates of behavioral and compositional preferences of musical harmony. Neuroreport. 2011;22(5):212–216. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328344a689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidelman GM, Krishnan A, Gandour JT. Enhanced brainstem encoding predicts musicians’ perceptual advantages with pitch. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;33(3):530–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling DL, Gill K, Choi JD, Prinz J, Purves D. Major and minor music compared to excited and subdued speech. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2010;127(1):491–503. doi: 10.1121/1.3268504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box GEP, Cox DR. An analysis of transformations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B - Statistical Methodology. 1964;26(2):211–252. [Google Scholar]

- Brattico E, Pallesen KJ, Varyagina O, Bailey C, Anourova I, Jarvenpaa M, et al. Neural discrimination of nonprototypical chords in music experts and laymen: an MEG study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;21(11):2230–2244. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budge H. A study of chord frequencies. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University; 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Burns EM. Intervals, Scales, and Tuning. In: Deutsch D, editor. The Psychology of Music. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 215–264. [Google Scholar]

- Burns EM, Sampat KS. A note on possible culture-bound effects in frequency discrimination. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1980;68(6):1886–1888. doi: 10.1121/1.385179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns EM, Ward WD. Categorical perception - phenomenon or epiphenomenon: Evidence from experiments in the perception of melodic musical intervals. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1978;63(2):456–468. doi: 10.1121/1.381737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcagno S, Plack CJ. Subcortical plasticity following perceptual learning in a pitch discrimination task. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 2011;12(1):89–100. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AS, Ho YC, Cheung MC. Music training improves verbal memory. Nature. 1998;396(6707):128. doi: 10.1038/24075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran B, Gandour JT, Krishnan A. Neuroplasticity in the processing of pitch dimensions: A multidimensional scaling analysis of the mismatch negativity. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 2007;25(3–4):195–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran B, Krishnan A, Gandour JT. Relative influence of musical and linguistic experience on early cortical processing of pitch contours. Brain and Language. 2009;108(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delogu F, Lampis G, Olivetti Belardinelli M. Music-to-language transfer effect: May melodic ability improve learning of tonal languages by native nontonal speakers? Cognitive Processing. 2006;7(3):203–207. doi: 10.1007/s10339-006-0146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delogu F, Lampis G, Olivetti Belardinelli M. From melody to lexical tone: Musical ability enhances specific aspects of foreign language perception. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 2010;22(1):46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch D, Henthorn T, Marvin E, Xu H. Absolute pitch among American and Chinese conservatory students: Prevalence differences, and evidence for a speech-related critical period. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2006;119(2):719–722. doi: 10.1121/1.2151799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling WJ. Scale and contour: Two components of a theory of memory for melodies. Psychological Review. 1978;85(4):341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Eberlein R. Die Entstehung der tonalen Klangsyntax [The origin of tonal-harmonic syntax] Frankfurt: Peter Lang; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Foster NE, Zatorre RJ. A role for the intraparietal sulcus in transforming musical pitch information. Cerebral Cortex. 2010;20(6):1350–1359. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin MS, Sledge Moore K, Yip CY, Jonides J, Rattray K, Moher J. The effects of musical training on verbal memory. Psychology of Music. 2008;36(3):353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka T, Trainor LJ, Ross B, Kakigi R, Pantev C. Musical training enhances automatic encoding of melodic contour and interval structure. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16(6):1010–1021. doi: 10.1162/0898929041502706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaab N, Schlaug G. The effect of musicianship on pitch memory in performance matched groups. Neuroreport. 2003;14(18):2291–2295. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200312190-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith G, Threadgill M, Hemsley J, Salour K, Songdej N, Ton J, et al. Putative measure of peripheral and brainstem frequency-following in humans. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;292:123–127. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandour JT. Tone perception in Far Eastern languages. Journal of Phonetics. 1983;11:149–175. [Google Scholar]

- Gandour JT. Tone dissimilarity judgments by Chinese listeners. Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 1984;12:235–261. [Google Scholar]

- Gandour JT. Phonetics of tone. In: Asher R, Simpson J, editors. The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. New York: Pergamon Press; 1994. pp. 3116–3123. [Google Scholar]

- Gao E, Suga N. Experience-dependent corticofugal adjustment of midbrain frequency map in bat auditory system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(21):12663–12670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern AR, Martin JS, Reed TD. An ERP study of major-minor classification in melodies. Music Perception. 2008;25(3):181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G, Poeppel D. Dorsal and ventral streams: a framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition. 2004;92(1–2):67–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KL, Nicol TG, Kraus N. Brain stem response to speech: A biological marker of auditory processing. Ear and Hearing. 2005;26(5):424–434. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000179687.71662.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishon-Rabin L, Amir O, Vexler Y, Zaltz Y. Pitch discrimination: Are professional musicians better than non-musicians? Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology. 2001;12(2):125–143. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.2001.12.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S, Gunter TC, v Cramon DY, Zysset S, Lohmann G, Friederici AD. Bach speaks: A cortical “language-network” serves the processing of music. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):956–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S, Jentschke S. Differences in electric brain responses to melodies and chords. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;22(10):2251–2262. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S, Schroger E, Tervaniemi M. Superior pre-attentive auditory processing in musicians. Neuroreport. 1999;10(6):1309–1313. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199904260-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A. Human frequency following response. In: Burkard RF, Don M, Eggermont JJ, editors. Auditory evoked potentials: Basic principles and clinical application. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 313–335. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Bidelman GM, Gandour JT. Neural representation of pitch salience in the human brainstem revealed by psychophysical and electrophysiological indices. Hearing Research. 2010;268(1–2):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Gandour JT. The role of the auditory brainstem in processing linguistically-relevant pitch patterns. Brain and Language. 2009;110(3):135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Gandour JT, Bidelman GM. The effects of tone language experience on pitch processing in the brainstem. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2010;23:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Gandour JT, Bidelman GM, Swaminathan J. Experience-dependent neural representation of dynamic pitch in the brainstem. Neuroreport. 2009;20(4):408–413. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283263000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn KI, Brattico E, Valimaki V, Tervaniemi M. Neural representations of the hierarchical scale pitch structure. Music Perception. 2007;24(3):281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Krumhansl CL. Cognitive foundations of musical pitch. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Hung TH. Identification of Mandarin tones by English-speaking musicians and nonmusicians. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2008;124(5):3235–3248. doi: 10.1121/1.2990713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Lee YF. Perception of musical pitch and lexical tones by Mandarin-speaking musicians. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2010;127(1):481–490. doi: 10.1121/1.3266683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitin DJ, Rogers SE. Absolute pitch: Perception, coding, and controversies. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt H. Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1971;49(2):467–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maess B, Koelsch S, Gunter TC, Friederici AD. Musical syntax is processed in Broca’s area: An MEG study. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4(5):540–545. doi: 10.1038/87502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie C, Kujala T, Besson M. Musical and linguistic expertise influence pre-attentive and attentive processing of non-speech sounds. Cortex. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2010.1011.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie C, Magne C, Besson M. Musicians and the metric structure of words. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2010;23(2):294–305. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques C, Moreno S, Castro SL, Besson M. Musicians detect pitch violation in a foreign language better than nonmusicians: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19(9):1453–1463. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.9.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheyl C, Delhommeau K, Perrot X, Oxenham AJ. Influence of musical and psychoacoustical training on pitch discrimination. Hearing Research. 2006;219(1–2):36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Besson M. Influence of musical training on pitch processing: Event-related brain potential studies of adults and children. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005;1060:93–97. doi: 10.1196/annals.1360.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Marques C, Santos A, Santos M, Castro SL, Besson M. Musical training influences linguistic abilities in 8-year-old children: More evidence for brain plasticity. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19(3):712–723. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchia G, Strait D, Kraus N. Relationships between behavior, brainstem and cortical encoding of seen and heard speech in musicians and non-musicians. Hearing Research. 2008;241(1–2):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen KJ, Brattico E, Bailey CJ, Korvenoja A, Koivisto J, Gjedde A, et al. Cognitive control in auditory working memory is enhanced in musicians. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantev C, Oostenveld R, Engelien A, Ross B, Roberts LE, Hoke M. Increased auditory cortical representation in musicians. Nature. 1998;392(6678):811–814. doi: 10.1038/33918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantev C, Roberts LE, Schulz M, Engelien A, Ross B. Timbre-specific enhancement of auditory cortical representations in musicians. Neuroreport. 2001;12(1):169–174. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200101220-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parbery-Clark A, Skoe E, Kraus N. Musical experience limits the degradative effects of background noise on the neural processing of sound. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(45):14100–14107. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3256-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parbery-Clark A, Skoe E, Lam C, Kraus N. Musician enhancement for speech-in-noise. Ear and Hearing. 2009;30(6):653–661. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181b412e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AD. Music, language, and the brain. NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peretz I. Brain specialization for music. New evidence from congenital amusia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;930:153–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfordresher PQ, Brown S. Enhanced production and perception of musical pitch in tone language speakers. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2009;71(6):1385–1398. doi: 10.3758/APP.71.6.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping L, Sepanski S, Zhao X. Language history questionnaire: A Web-based interface for bilingual research. Behavior Research Methods. 2006;38(2):202–210. doi: 10.3758/bf03192770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plack CJ, Oxenham AJ, Fay RR, Popper AN, editors. Pitch: Neural coding and perception. Vol. 24. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Poeppel D, Idsardi WJ, van Wassenhove V. Speech perception at the interface of neurobiology and linguistics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences. 2008;363(1493):1071–1086. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg EG, Peretz I. Music, language and cognition: unresolved issues. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12(2):45–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg EG, Trehub SE. Is there an Asian advantage for pitch memory. Music Perception. 2008;25(3):241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Schon D, Magne C, Besson M. The music of speech: Music training facilitates pitch processing in both music and language. Psychophysiology. 2004;41(3):341–349. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoe E, Kraus N. Auditory brain stem response to complex sounds: A tutorial. Ear and Hearing. 2010;31(3):302–324. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181cdb272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slevc LR, Miyake A. Individual differences in second-language proficiency: Does musical ability matter? Psychological Science. 2006;17(8):675–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slevc LR, Rosenberg JC, Patel AD. Making psycholinguistics musical: Self-paced reading time evidence for shared processing of linguistic and musical syntax. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16(2):374–381. doi: 10.3758/16.2.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohmer H, Pratt H, Kinarti R. Sources of frequency-following responses (FFR) in man. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1977;42:656–664. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(77)90282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagray JR, Downs D. Differential sensitivity for frequency among speakers of a tone and nontone language. Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 1993;21(1):143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Strait DL, Kraus N, Parbery-Clark A, Ashley R. Musical experience shapes top-down auditory mechanisms: Evidence from masking and auditory attention performance. Hearing Research. 2010;261(1–2):22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga N. Role of corticofugal feedback in hearing. Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 2008;194(2):169–183. doi: 10.1007/s00359-007-0274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervaniemi M, Just V, Koelsch S, Widmann A, Schroger E. Pitch discrimination accuracy in musicians vs nonmusicians: an event-related potential and behavioral study. Experimental Brain Research. 2005;161(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervaniemi M, Kruck S, De Baene W, Schroger E, Alter K, Friederici AD. Top-down modulation of auditory processing: effects of sound context, musical expertise and attentional focus. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;30(8):1636–1642. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WF, Schellenberg EG, Husain G. Decoding speech prosody: Do music lessons help? Emotion. 2004;4:46–64. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong PC, Skoe E, Russo NM, Dees T, Kraus N. Musical experience shapes human brainstem encoding of linguistic pitch patterns. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10(4):420–422. doi: 10.1038/nn1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. Tone in connected discourse. In: Brown K, editor. Encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 742–750. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Gandour J, Talavage T, Wong D, Dzemidzic M, Tong Y, et al. Activation of the left planum temporale in pitch processing is shaped by language experience. Human Brain Mapping. 2006;27(2):173–183. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip M. Tone. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zarate JM, Zatorre RJ. Experience-dependent neural substrates involved in vocal pitch regulation during singing. Neuroimage. 2008;40(4):1871–1887. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.