Abstract

U.S. immigrants have faced a changing landscape with regard to immigration enforcement over the last two decades. Following the passage of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, and the creation of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency after the attacks of September 11, 2001, detention and deportation activity increased substantially. As a result, immigrants today are experiencing heightened fear of profiling and deportation. Little research exists on how these activities affect the health and well-being of U.S. immigrant communities. This study sought to address this gap by using community-based participatory research to investigate the impact of enhanced immigration enforcement on immigrant health in Everett, Massachusetts, USA, a city with a large and diverse immigrant population. Community partners and researchers conducted 6 focus groups with 52 immigrant participants (documented and undocumented) in five languages in May 2009. The major themes across the groups included: 1) Fear of deportation, 2) Fear of collaboration between local law enforcement and ICE and perception of arbitrariness on the part of the former and 3) Concerns about not being able to furnish documentation required to apply for insurance and for health care. Documented and undocumented immigrants reported high levels of stress due to deportation fear, which affected their emotional well-being and their access to health services. Recommendations from the focus groups included improving relationships between immigrants and local police, educating immigrants on their rights and responsibilities as residents, and holding sessions to improve civic engagement. Immigration enforcement activities and the resulting deportation fear are contextual factors that undermine trust in community institutions and social capital, with implications for health and effective integration processes. These factors should be considered by any community seeking to improve the integration process.

Keywords: Immigrants; Immigration and Customs Enforcement; USA; deportation fear; 9/11; stress, access to care; community-based participatory research

Background

U.S. immigrants have faced a changing landscape with regard to immigration enforcement over the last two decades After the passage of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IRRIRA) of 1996, detention of illegal immigrants increased and the categories for persons subject to detention expanded along with the types of crimes for which noncitizens could be deported (Miller, 2005). With the creation of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), a new division within the Department of Homeland Security, following the attacks of September 2011, the growth of detention and deportation activities accelerated (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2009). Now, with the advent of section 287(g) agreements which allow local police officers to carry out enforcement of federal immigration law ( Rodriguez, Chishti, Capps, & St. John, 2010) even longtime documented immigrants are being targeted for deportation for minor offenses ( Miller, 2005).

Simultaneously, there has been a progressive shift in responsibility for immigration policy and enforcement from the federal government to states and locales (Fix & Tumlin, 1997; Suarez-Orozco & Suarez-Orozco, 2009). Communities where immigrant populations are most concentrated are struggling to address the strains associated with the influx of diverse and, at times, undocumented populations. Local institutions, including police departments, schools, and health systems, are developing their own de-facto policies to accommodate these new populations (Steinberg, 2008). At times, these local policies directly conflict with federal ICE mandates. For example, the 2007 ICE raids in New Haven, CT occurred within days of the city adopting a “resident identification card” that allowed documented and undocumented immigrants to open bank accounts and use other municipal services (www.Eyewitness News 3, 2007).

The contextual factors present in receiving communities greatly influence the assimilation patterns of new immigrants. According to segmented assimilation theory, immigrants follow divergent assimilation paths based in part on the characteristics of the host community (Portes, Fernandez-Kelly, & W., 2005; Portes & Rumbaut, 2006; Zhou, 1997). Community context includes socio-economic conditions and governmental policies which may support or impede assimilation including discrimination, bifurcated labor markets, poverty and crime (Portes et al., 2005; Xie & Greenman, 2005). Immigration enforcement policies related to detention and health care access are important contextual factors influencing the integration process. For example, the negative effect of detention and temporary status on the mental health of asylum seekers has been well documented in Australia, Japan, and Europe (Ichikawa, Nakahara, & Wakai, 2006; Keller, Rosenfeld, Trinh-Shevrin, Meserve, Sachs, Leviss et al., 2003; Silove, Steel, & Mollica, 2001). Sequelae of policies that limit immigrants access to health care have been documented in Germany, Spain and Canada among others (Castaneda, 2009; Magalhaes, Carrasco, & Gastaldo, 2010; Torres & Sanz, 2000).

The daily threat of discovery and deportation is likely to create fear and emotional distress for both documented and undocumented immigrants, thus impeding integration (K. E. Miller & Rasmussen, 2010; Silove et al., 2001; Steinberg, 2008). So too, the loss of loved ones who are detained or deported may create unexpected economic challenges and new responsibilities for children left behind (Chaudry, Capps, Pedroza, Castaneda, Santos, & Scott, 2010). According to Viruell-Fuentes (2007), immigrants’ experience of stigmatization translates to stress, isolation, and marginalization. This may lead to depression and anxiety, as well as lack of personal empowerment and self-advocacy (Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Thus, this chronic fear may have a deep negative impact on integration as well as health outcomes.

In the U.S., the effects of ICE activity on immigrant stress levels and health status have only recently been examined (Capps, Castañeda, Chaudry, & Santos, 2007; Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition, 2010; Steinberg, 2008). Studies on the impact of Proposition 187, a 1994 California state ballot initiative which prevented undocumented immigrants from accessing publicly funded health care, found that immigrants feared obtaining medical care and delayed or discontinued care as a result (Asch, Leake, Anderson, & Gelberg, 1998; Asch, Leake, & Gelberg, 1994; Berk & Schur, 2001; Fenton, Catalano, & Hargreaves, 1996). Deportation fear has also been associated with poorer self-perceived health, and activity limitation following ICE raids (Cavazos-Rehg, Zayas, & Spitznagel, 2007; Steinberg, 2008).

In the last fifteen years, Massachusetts cities have become home to increasing numbers of immigrant residents. In 2007, over 14% percent of Massachusetts residents were immigrants (Clayton-Mathews, Karp, & Watanabe, 2009). Everett, Massachusetts, with a population of 38,037, is an exampleof a city that has experienced rapid diversification, with immigrants predominantly coming from Haiti, Central America, Brazil and North Africa (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Today, Everett hosts the fourth largest concentration of immigrants in the state (34.8%) (Clayton-Mathews et al., 2009; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

Rising concerns about the impact of ICE activities on immigrant health emerged in 2009 as Everett community members reported immigrants missing health appointments due to their fear of being stopped en route by ICE or local police and deported. This concern was validated with a brief questionnaire of local health providers. As a result, members of the Everett community representing local organizations, churches and immigrant led advocacy groups approached researchers at the Institute for Community Health to examine this issue in depth using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach.

The goal of this CBPR project was to determine whether increased ICE activity was affecting the health and health care of immigrants in Everett. Specifically, the project sought to: 1) Learn more about the impact of ICE activities on immigrant health through a series of focus groups with a diverse population of immigrants, and 2) Develop a set of recommendations for community action. The data described herein provide insight into the concerns and fears of immigrants and the factors contributing to them. The analysis of these perspectives provides information that can be used to inform local policies here and abroad in communities that are experiencing rapid diversification through immigration.

The Setting

As a community, Everett has attempted to integrate newly arriving immigrants into the fabric of the city. The Multicultural Affairs Commission (MAC) was created in 2005 and included immigrant and non-immigrant members. MAC efforts included: monthly Everett Dialogues with immigrants and city leaders, community forums to assess and improve immigrant access to health care services, a “Welcome To Everett” guide on city services and regulations for all newcomers to Everett and other projects including a youth/elder oral history project that paired recently arrived immigrant youth with older long term residents. Such channels of communication also allowed immigrant communities to voice their concerns about ICE activities in Everett.

Six Everett community agencies, many members of the MAC, who had been actively involved in addressing immigrant issues in Everett, were involved in the research project: the Joint Committee for Children’s Health Care in Everett (JCCHCE), the Everett Literacy Program, the Muslim American Civic and Cultural Association (MACCA), Immaculate Conception and St. Anthony’s Catholic churches, La Comunidad, Inc., and the Everett police department. The JCCHCE focuses its efforts on improving access to health care and is actively involved in enrollment in both insurance and in the state Health Care Safety Net program (“Health Safety Net-HSN (Free Care): An Overview,” 2010). The two Catholic churches’ congregations include large numbers of Haitians and Brazilians. La Comunidad and MACCA are emerging immigrant service organizations focused on Latinos and the Arab and Muslim population respectively and both are led by immigrants. The Everett Literacy Program provides the majority of English Second Language courses in Everett. Representatives from these groups had extensive experience in coalition building, community organizing, and addressing immigrant concerns. Representatives also participated from the Everett Community Health Partnership; a collaborative of the Cambridge Health Alliance, the Everett Police Department, the Everett Public Schools and the City of Everett.

Research support included scientists from the Institute for Community Health, health care providers from the Cambridge Health Alliance, and researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health and Tufts Medical School. They contributed diverse expertise in clinical issues, qualitative and quantitative methods, CBPR, immigrant health, and demography.

Methods

Community-Based Participatory Research

A CBPR approach calls for the participation of community partners in every aspect of the research process, from problem identification to dissemination of results (Israel, Schulze, Parker, & Becker, 1998). In this study members of the communities at risk identified the problem for study and approached researchers to help them answer their questions. They were critical partners in recruitment, conduct and analysis of the research, and the promulgation of recommendations. Given the highly sensitive nature of the issues under investigation, it would have been impossible to access the multiple immigrant groups without their engagement.

The project ran from February 2009 through February 2010. The team of community members and investigators met regularly as a working group of 10 members throughout the project. Human subjects’ approval for the study was obtained from the Cambridge Health Alliance on February 30, 2009. Community partners were included in the IRB submission as co-investigators.

Conceptual Framework

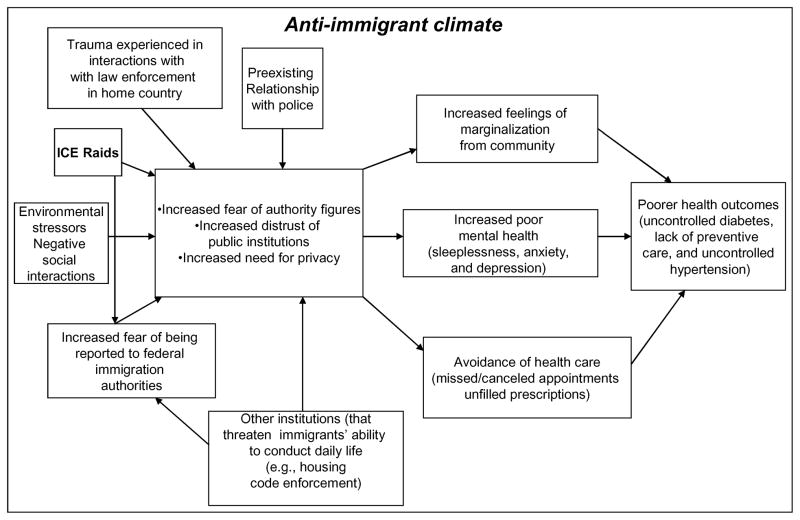

The working group began by developing a conceptual framework that illustrated the various ways in which increased immigration enforcement efforts might impact immigrant health (Fig. 1). After an initial discussion, researchers drafted a framework that was then continually refined by the working group, supplemented with additional factors and used to highlight important components. For example, community members identified issues surrounding driver’s licenses, and the lack thereof, as a major problem leading to arrests and consequently, to missed health care appointments. They also raised concerns about how immigrants viewed the relationships between local police and ICE based on prior experiences in their countries of origin. The resulting collaboratively developed framework not only helped guide the project but illuminated new areas for investigation that would not have been identified without a CBPR approach.

Figure 1.

Impact of ICE Activities on Immigrant Health Conceptual Framework

Focus Group design

To investigate the primary questions of interest, the working group chose to utilize a focus group methodology. Focus groups allow for an in-depth examination of issues and given the sensitive nature of the work, also allow for data to be collected in a safe, non-threatening manner that encourages honest responses. Community members chose to conduct focus groups with the predominant immigrant groups - Spanish speakers (mostly Central Americans), Portuguese speakers (Brazilians), Haitian Creole speakers, and Arabic speakers (predominantly Moroccans) - in order to capture perspectives across Everett. They also decided to conduct several mixed heritage English language focus groups to incorporate immigrants from other countries and provide a dialogue between immigrant groups.

The working group met several times to design the focus group moderator’s guide. The guide built on the conceptual framework and included questions about the immigrant experience in the U.S.; questions about the impact of immigration enforcement on overall community anxiety and fear; and questions on the impact of any fear or anxiety on health and health seeking behaviors. Additional questions on experiences with law enforcement (i.e. the Everett police) and the perceived relationship between local police and ICE were asked to better understand how community members interpreted these interactions. The focus group closed with questions on perceptions of safety and security and asked what recommendations would improve the lives of immigrants. A short survey was used at the beginning of the focus groups to capture information on demographics and prior use of health care services.

Participants/recruitment

Criteria for participation included being foreign-born and resident in Everett. Facilitators, who were bilingual immigrant community members representing the dominant language groups (Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, and Haitian Creole), were responsible for recruitment. These individuals had extensive networks of immigrant community contacts and could effectively conduct outreach to the communities of interest. They used snowball sampling-that is asking one person to ask another-and tried to insure that their groups were diverse in age, gender, legal status, and use of the health care system. Facilitators-who were community members, asked about legal status before the focus groups began. Similar to classification schemes used in other studies, immigrants who were either U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents were considered documented and those who were not were considered undocumented (M. A. Rodriguez, Bustamante, & Ang, 2009).

Conduct of the Focus Groups

Based on conversations with immigrant representatives and potential participants, we were strongly discouraged from making audio-recordings. We were told that this would dissuade participation and thus decided against using audio-tape. Instead, bilingual note-takers (2 pergroup) wrote in the language of the group and later translated their notes into English. In all but one focus group, one of the notetakers was a member of the research team. The research team provided a two-hour training for the facilitators and note-takers on research ethics and how to conduct a focus group and record information.

Six focus groups were held in May 2009 in familiar Everett locations that were comfortable for immigrant participants (churches and agency offices). Prior to beginning each group, the facilitator read the consent form aloud and verified that everyone understood the content. Acknowledging the sensitivity of the topic area, consent was obtained by a show of hands rather than signature. Participants were also given the anonymous pre-survey translated into their own language to fill out.

Analysis

Immediately following focus groups, facilitators and notetakers were asked to provide initial impressions of themes drawn from the groups via an electronic survey. Notetakers from non- English-speaking groups then translated their notes into English. Notes from each focus group were combined into one version and validation was done with the facilitator of the group who reviewed the notes for accuracy. Subsequently, a meeting that included both research team members and community facilitators took place to debrief from the focus groups and identify emerging themes.

In the next phase, a smaller subcommittee made up of six researchers collected all the notes and utilized the emerging themes as categories to code content. Initially, each researcher reviewed the focus group that they had attended and coded statements according to the emerging themes while also looking for additional themes. Then the subcommittee reconvened to review the themes, assess missing and/or combined themes in each of the focus groups and agree upon a thematic codebook. The subcommittee then presented to the working group for input and incorporated their feedback into a revised codebook which was used to recode the focus group data. Finally, the subcommittee examined common and divergent themes across the focus groups. This information was also submitted back to the working group to ensure that the agreed upon categories were consistent with their perceptions.

Results

Fifty-two immigrants participated in the focus groups. Their demographics and health characteristics are shown in Table 1. This ethnically and linguistically diverse population was mostly female (65%), had health insurance (75%), had seen a doctor in the last year (71%) and were largely undocumented (63%).

Table 1.

Demographics of the Focus Groups

| Total | Arabic | Portuguese | Haitian Creole | Spanish | English 1 | English 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=52 N |

N=8 N |

N=8 N |

N=8 N |

N=8 N |

N=8 N |

N=12 N |

|

| Age | |||||||

| 19–29 | 15 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 30–45 | 17 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 46–59 | 16 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| >60 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Country of Origin | |||||||

| Morocco | 8 | 8 | |||||

| Brazil | 18 | 8 | 3 | 7 | |||

| Haiti | 11 | 8 | 1 | 2 | |||

| El Salvador | 9 | 5 | 2 | 2 | |||

| China | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Peru | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Guatemala | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Columbia | 11 | 1 | |||||

| Documented | |||||||

| Yes | 19 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| No | 33 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 10 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 19 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Female | 33 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 10 |

| Education* | |||||||

| Primary | 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Some High School | 21 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| High School Grad | 11 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Some College | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Completed College | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| City | |||||||

| Everett | 36 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 9 |

| Other | 16 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Health Insurance | |||||||

| Yes | 39 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| No | 13 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Saw a Doctor in Last Year | |||||||

| Yes | 37 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8 | |

| No | 15 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

Two of the Haitian Creole group did not respond to the Education question

Focus Groups

A number of common themes spanned all of the focus groups; however four themes were particularly salient.

-

1)

Fear of deportation: Undocumented participants spoke of the ever present fear that at any time, they might be arbitrarily picked up and deported back to their country of origin. Documented participants were concerned for the welfare of family and friends.

-

2)

Perception of collaboration between local law enforcement and ICE leading to unlimited discretion to arrest immigrants: Participants–regardless of documentation status-believed that the local police were an arm of a larger federal authority and were working closely with ICE. There was also a belief that local and state police had the authority to deport individuals.

Both of these themes had implications for additional themes related to access to health care and perceived health which included:

-

3)

Concerns about documentation required for insurance and health care: Both documented and undocumented immigrants discussed fears that giving out personal information to acquire health insurance or health care would be reported to ICE.

-

4)

Fear of deportation and its relationship to emotional well-being and health care compliance: Documented and undocumented participants in all groups reported feelings of anxiety and hopelessness resulting from the ever present fear of deportation. In some cases this led to avoidance of care (missed appointments, refusal to complete state documents to obtain health coverage and subsequent lack of insurance).

Fear of Deportation

Fear of deportation was identified by members in all focus groups. Individuals expressed anxiety about being asked for documentation and “picked up” indiscriminately by authorities.

There is a fear of being deported if they (immigrants) don’t have papers, or if they do something “bad”. Even minor infractions of the law, such as a traffic violation, can get someone deported. (Haitian Creole-speaking participant)

I am too scared to ask for help. For everything they request documents. For everything they ask for the social security number. I am always scared, there is always fear. (Spanish-speaking participant)

The unpredictable nature of ICE activity and deportation described in numerous stories of disappearing friends and relatives made people feel helpless in the face of powerful authorities and added to their sense of vulnerability.

They (ICE) go with paper and if [they are] looking for someone above, if they accidentally go to the first floor and you don’t have documentation they will take you anytime, you never know. I have a friend who used to live in Chelsea and was taken by immigration. (English-speaking participant)

Some even worried that other immigrants would report them to authorities.

ICE came to my house at 7 in the morning back in 2004. Our neighbor sold us out. I was very scared. They wanted to check the house, claiming that I was hiding illegal people. …I really thought I was going to be deported at that moment… (Arabic-speaking participant)

While one might assume that only undocumented immigrants would experience this fear, documented immigrants were also fearful for their family members or because their own “status” might be questioned.

Back in 2004 they came in to my house too and told me that I was hosting a lot of undocumented immigrants and that they were sleeping on the floor. I was lucky I had a work permit back then and none of that information they had was true and they asked me if I worshiped in a mosque on regular basis and if I knew of any plot or attack that was going to take place against the U.S. I was very scared. (Arabic-speaking participant)

Many participants were particularly worried about the impact of ICE activity and deportation on their children or on children of other immigrants. They reported numerous stories of children being left behind when parents were picked up and taken by ICE.

My sister-in-law had 2 girls. She got deported and someone else had to take care of the children (English-speaking participant)

Overall, deportation fear seemed to affect all the immigrants in the focus groups, regardless of their documentation or their country of origin. The ever-present concern that at any time, ICE might take you from your family, created an environment of insecurity.

(I) want to feel safe but I cannot. Sometimes I want to go somewhere but I am afraid, if they take me while I am away, I couldn’t forgive myself because I would leave my son and husband. It changes the way I live. (English-speaking participant).

Any time I leave my house, I don’t know if I will be arrested and deported. I tell my kids if I get deported you have to take care of each other… (Arabic-speaking participant)

Relationships between Police and ICE

Given the fear expressed about deportation, it was not surprising that both local and state law enforcement officials were perceived to be closely related to ICE. The distrust for law enforcement was expressed in all the focus groups. In some cases the perception of police connection to ICE was reflective of the situation in their own countries.

The separation between the police and ICE is something hard to understand as in Brazil they are all interconnected. (Portuguese-speaking participant)

(I) don’t feel free to go to police department and report a crime. (I’m) afraid to say because they might take me to investigation. I can’t share information with the police. I am afraid because I am undocumented. (English-speaking participant)

This perceived connection between ICE and police only serves to increase fear as many immigrants discussed being targeted and stopped by police for no particular reason and assumed that the next step would be deportation.

Once I was shopping for groceries…and when I stepped out of the supermarket to put my bags in the car, I noticed a police officer checking me out. When I entered my car and turned it on, she came up behind me with her lights on, asking for my driver’s license.....(Portuguese-speaking participant)

Despite not having valid driver’s licenses, many undocumented immigrants continued to drive out of necessity, needing to transport their families and get to their jobs. In the Everett area, while there is limited public transportation (buses) driving is often essential especially since equipment (cleaning devises, painting tools, etc) is needed for jobs and distances to employment are not walkable. However, many felt that they were targeted by authorities for minor violations and only then identified as undocumented. This in turn could lead to arrest or other consequences. These “traffic stops” made immigrants hyper-vigilant about the police presence in Everett.

He (a friend) does not understand how come the police officers have no definite set of rules to follow, when they pull over a driver with no driver’s license. Some of them send the person to jail, some tow the car and some just let the person go. (Portuguese-speaking participant)

It also caused some to report taking alternate routes in order to avoid streets where they had experienced negative interactions with police.

Police stopped me 2 years ago. I take an alternate route, [I am] afraid to pass the place where police stopped me. It takes more time. (English-speaking participant)

Overall, the fear of deportation and the distrust of police were prominent themes throughout the focus groups. While undocumented immigrants were particularly vocal about this, documented immigrants were also impacted, not only in cases of mistaken identity, but also by the deportation of relatives and friends.

Obstacles to Health Care

Many felt that the documentation required to obtain health insurance was an obstacle to getting the care they needed. In Massachusetts, individuals such as undocumented immigrants who are ineligible for insurance, can access the Health Safety Net program. This state funded program provides payment for health care.(“Health Safety Net-HSN (Free Care): An Overview,” 2010) While not actually insurance, most immigrants do not differentiate it from insurance. However, enrollment requires documentation and renewals are required frequently. Thus, whether obtaining insurance, or “Health Safety Net”, immigrants still worried that by disclosing their legal status they would be vulnerable to ICE or law enforcement action and as a result some immigrants avoided using the health care system.

I won’t go to the hospital because they usually want information and if I don’t have them, they call ICE. I rather stay home to feel safe. (Haitian Creole-speaking participant)

I was always afraid to go to the hospital, but I forced myself when my son got sick. I got Masshealth, but as soon as I heard about the New Bedford incident [a workplace raid to identify undocumented workers which occurred in New Bedford, Massachusetts]), I called Masshealth and told them I was moving to another state so they can cancel it. I wanted to minimize the risk of getting caught. (Arabic-speaking participant)

In some cases, avoidant behavior led to neglecting health needs.

I know a lady whose husband was deported. She has 14 cavities in her mouth and she wouldn’t go to the dentist and seek medical help because of fear…(Arabic-speaking participant)

While fears about disclosure were prioritized, all of the groups identified cost as a further obstacle to getting health care.

Impact of Fear on Health and Mental Health

Participants noted that their fear of deportation impacted both their physical conditions and their emotional health. For some, this resulted in missing health care appointments when ICE was in the vicinity.

There was an ICE raid in East Boston. My mother was afraid to go to her visit… My brother was supposed to take my mom to the clinic and he couldn’t go cause ICE was on the street and he was afraid. (English-speaking participant)

For others, fear was blamed for specific health outcomes such as depression and hypertension.

The fear is causing stress and depression. People are afraid of police, afraid to go out, afraid to walk on the street. You don’t want people to be scared of you, to call the police on you. How could you not have stress? I’m young. All my hair is falling out. (Haitian Creole-speaking participant)

For my boyfriend, it raises his blood pressure. He is scared of everything. (Spanish-speaking participant)

Additional Themes

While the purpose of this study was to understand the relationship between ICE activity and health, discrimination based on race and or ethnicity emerged as a common theme across focus groups.

I have three strikes (a term used in baseball referring to three strikes and you are out of the game) against me; female, black, immigrant. (Haitian Creole-speaking participant)

It only happens to the Hispanic. Never a White. Police always have a hidden agenda for Hispanics. (Spanish-speaking participant)

The Arabic-speaking group spoke about their experience with ethnic discrimination. One individual provided a story regarding her own deportation:

They [ICE] came to my doorstep, they said you’re coming with us and the officer wanted to handcuff me in front of my kids. I told him please don’t do it [in] front of my kids and mom and he said you have no right these are the rules, until another officer told him to do it. When they put me in the car, on the way they started to ask me if I had any ties with Al Qaeda and they asked me if I know Bin Laden personally.… they ask me to remove my scarf (hejab). Even if it’s against my religion to take it off… (Arabic-speaking participant)

The Arabic-speaking group was the only group to express a sense of defiance and injustice regarding ICE. They urged people to confront immigration and local law enforcement authorities and know their rights rather than remain helpless.

I don’t care anymore because I’m sick of it. Why are we asked if we’re legal or not? We pay our taxes like everybody else. Get out there and know your rights! ASK, ASK, ASK, you need to know your rights. (Arabic-speaking participant)

Recommendations from groups

At the end of each focus group, participants were asked to provide strategies for improving their lives in Everett. Suggestions fell into four main areas:

Immigrants identified the need for additional information on several subjects: health care access (what to expect in health care facilities), on the differences between local law enforcement and ICE, and on their rights and responsibilities as Everett residents. They felt that this information should be widely disseminated through natural channels such as churches, schools, and media outlets.

The majority of participants identified the need for more advocacy to reform immigration law, to provide drivers’ licenses to all, and to expand access to higher education for undocumented children.

Many felt that training in cultural competency for police, health care workers and city hall staff would improve relationships with immigrant communities. They also felt that the workforce should be diversified to reflect the populations residing in Everett.

Participants recommended immigrant-police community meetings where issues could be discussed and communication improved.

Discussion

The study of social and behavioral determinants of health increasingly reveals the role that environmental stressors play in individuals’ health. Segmented assimilation theory provides one lens through which to view the impact of these factors on integration trajectories of immigrants. Underlying integration processes are social relationships. While it is widely known that there is a causal link between social relationships and health (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988) less is known about the mechanisms and processes that inform this link. In this study, as outlined in our framework (Fig. 1), we explored the links between “fear of deportation” and immigrant health in an attempt to enhance our understanding of these mechanisms.

To date, research has identified social isolation and economic segregation along racial/ethnic lines as important determinants of heath status. So too, social capital and the accompanying access to both tangible and psychosocial resources, has been identified as a determinant of health (Kawachi, Subramanian, & Almeida-Filho, 2002). While studies show that immigrants in ethnic enclaves have high social connectedness through “kin-based” networks (relatives, extended family, other immigrants), these social networks can be fairly insular and thereby limit access to resources such as health care, social support programs and other city services (Viruell-Fuentes & Schulz, 2009). This has been described as “bonding” social capital but relationships outside these networks (“bridging social capital”) are also needed to insure access to services and knowledge that support health.(Kim, Subramanian, & Kawachi, 2006). “Trust” as a key aspect of social capital, has been linked in and of itself to various health outcomes (Subramanian, Kim, & Kawachi, 2002). The lack of “trust” in the institutions of a host community may diminish one’s ability to establish bridging social capital and thus result in negative health consequences (ranging from poor access to health services to poor mental health and isolation). In this study, we identified an overarching belief among focus group participants that those in positions of authority-police, health care personnel, and health insurers-had power to interact with ICE and initiate the deportation process. This belief was a major factor in undermining the “trust” that immigrants, particularly undocumented immigrants, had for their host communities. While one might assume that trust is expected to be less where the rule of law is weaker, this was not the case for our participants who instead, were in fear of the way that the law is exercised. Without trust, immigrants felt chronically insecure in their host community and were reticent to seek care when needed. Many of the factors that contribute to the vulnerability of immigrant communities are well described but how deportation fear contributes to this vulnerability and subsequently to health is less well understood (Derose, Bahney, Lurie, & Escarce, 2009). Thus our findings make an important contribution to clarifying the ways in which we conceptualize the processes that connect trust, social capital and health.

Health consequences of deportation fear

Deportation fear had a negative effect on health at both the individual and communal level. At the individual level, deportation fear affected healthcare access as well as emotional and physical health. Health access was decreased as a result of required documentation and due to the presence of police or ICE in the vicinity. While similar findings have been described elsewhere, (Asch et al., 1998; Asch et al., 1994; Berk & Schur, 2001; Castaneda, 2009; Magalhaes et al., 2010; McGuire & Georges, 2009) the connection between local law enforcement activity and health status has not been previously reported

From a physical and emotional perspective, participants noted that fear of deportation exacerbated their chronic diseases such as depression, high blood pressure, and anxiety while also producing a range of physical symptoms (hair loss, headaches). Past studies of the impact of chronic fear on health have focused mainly on crime related fear for those living in disadvantaged communities. Stafford et al. (2007) postulated that fear of crime leads to avoidance of both social and physical activity. This in turn may have a long term impact on vulnerability, self-medication, and immune response (Stafford, Chandola, & Marmot, 2007).

Similar to the fear of crime, the impact of chronic deportation fear may exacerbate current health conditions while increasing vulnerability to others. It may also reverberate across populations acting as a prolonged biological stressor with associated health consequences (Castaneda, 2009). In this study, for example, the impact of deportation fear was experienced across different immigrant groups regardless of their country of origin or immigration status. When immigrant communities do not trust their community institutions, they are less likely to fully engage as members of the community. This also has implications for the health of the city in which they live (Carpiano, 2006; Subramanian et al., 2002). When immigrant groups do not trust law enforcement and abstain from reporting crime, it is difficult to maintain security. When they avoid health care for communicable diseases, it becomes difficult to maintain the public’s health (Asch et al., 1998; Davis & Henderson, 2003; Lysakowski, Pearsall, & Pope, 2009).

As noted in other studies (Portes et al., 2005; Romero, Martinez, & Carvajal, 2007), the immigrants in this project also reported pervasive experiences of discrimination based not only on their immigrant status but also on their race or ethnicity. However, only the Arab participants expressed defiance over these events. Arabic communities have experienced significant profiling and discrimination since the terrorist attacks in the US on September 11, 2001 (Akram & Johnson, 2001–2003;Lauderdale, 2007). In addition, the negative depiction of Arabs as America’s enemies along with repeated longterm cultural stereotyping are likely to be root causes of the defiant attitudes we encountered (Wray-Lake, Syvertsen, & Flanagan, 2008). The context of reception for Arabic speakers is particularly challenging given these realities and while much has been written about the relationship between racism and health (Krieger, 2003; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2008), the specific relationship between deportation fear, racism and health in this population deserves further study.

Recommendations

Many of the recommendations from the focus groups echoed those highlighted in a recent Massachusetts report by the Governor’s Advisory Council on Refugees and Immigrants including those related to improved relationships between local law enforcement and immigrant communities (Egmont, Millona, Chacon, Tambouret, Hohn, & Borges-Mendez, 2009). As part of this CBPR study, these recommendations along with study results were presented to a large audience of immigrants, Everett city and school officials and local police for feedback and discussion. This forum produced a set of actionable citywide proposals that immigrant leaders are now taking forward. Many are actively involved with statewide advocacy groups seeking to reform national immigration law. As a first local step, the police and immigrant groups have met several times and initial reports from both community members and police suggest that communication is improving. Additionally, both parties have agreed to start a multi-lingual call-in cable TV show to discuss issues of interest, e.g., police traffic stops, domestic violence, and reporting crimes, This police/immigrant dialogue has the potential to reduce disinformation about law enforcement rules and regulations circulating among immigrants and simultaneously improve security for the community as a whole. This simple measure can be an effective tool to decrease deportation fear and could be adopted by other communities facing rapid diversification.

The findings from this study have important practical implications for Everett and other communities experiencing a rapid influx of immigrants. Given the current level of increased ICE activity, it is likely that immigrants nationwide are experiencing heightened deportation fear. Strategies to improve immigrant integration need to include the civic institutions that play critical roles in immigrants’ daily lives. Police departments must clarify and possibly adjust their relationships with ICE in order to develop and maintain trust with immigrant communities. Health care providers need to be aware of the stressors affecting their immigrant patients in order to provide appropriate care and health care institutions must consider ways to identify patients without creating further anxiety. Building trust will require all partners to provide a unified local response for success.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is based on a small sample of focus group participants who were recruited from one community and may not be representative of all immigrants in Everett or in other communities. However, the primary themes identified, including fear of deportation, were consistently noted across all focus groups regardless of language spoken or country of origin and echoed previous concerns voiced by immigrants in Everett. In addition, the pivotal role of immigrant advocacy organizations in the community helped to provide a safe space for discussion and allowed us to reach populations, including the undocumented, which would otherwise be unavailable for study. Successful research with these populations requires a safe place for data collection (Marcelli, Holmes, Estella, da Rocha, Granberry, & Buxton, 2009; Marcelli, Holmes, Troncosco, Granberry, & Buxton, 2009; Suro, 2005). We acknowledge that focus group participants may have had greater social capital and less fear than others given their relationship to immigrant leaders and willingness to voice their opinions. Thus, we speculate that the themes expressed are even more likely to resonate among others who prefer to remain anonymous. Alternatively, the leaders may have recruited like-minded individuals and thereby the participants may have reflected leaders’ opinions. We talked with the facilitators and found that most did not know the majority of participants in their groups, nor did they know the opinions they were likely to express. In fact, based on early discussions with the leaders, there were numerous unexpected findings in the focus groups that had not been anticipated, including the concerns surrounding the provision of documentation in health care facilities.

While we heard a great deal about stress and depression, we did not use validated tools to specifically assess these conditions and, therefore, are unable to determine whether participants suffered from specific mental health conditions.

Lastly, due to the confidential nature of the study, we were unable to record the content of the focus groups. However, by having native speakers take notes, translate information and subsequently vet the information with facilitators, we were able to obtain the important thematic content while maintaining trust.

Conclusion

As noted in Everett, Massachusetts, perceptions about the relationship between those in positions of local authority and national immigration policy can undermine trust in community institutions. Loss of trust can further marginalize an already vulnerable population by diminishing bridging social capital. This has implications for the health of individuals and the communities in which they live. As noted by Portes and Rumbaut, (2006) the “context of reception” for immigrants – that is the policies of the receiving government, conditions of the host labor market and the characteristics of ethnic communities - determine the incorporation trajectories of newcomers (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006). While national immigration reform remains elusive, each individual community - be it Everett or elsewhere – will continue to influence the integration of immigrant populations and as such be responsible for building the necessary trusting relationships to ensure immigrant health and well-being.

Research highlights.

Uses a community Based Participatory Research approach to examine the impact of US immigration enforcement policies on daily lives.

It contributes to our understanding of the mechanisms that undermine immigrant trust, social capital and health

One of the few studies to identify common impediments to integration across immigrant groups of mixed documentation status

By providing new perspectives on the acculturation paradigm, this study helps operationalize the “context of reception”

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH Award #UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, the National Center for Research Resources, or the National Institutes of Health. In addition, we would like to thank all the immigrants who shared their stories with us during the focus groups. Without them the work would not have been possible

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Karen Hacker, Institute for Community Health, Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School

Jocelyn Chu, Institute for Community Health, Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School

Carolyn Leung, Tufts Clinical Translational Science Institute, Tufts Medical School, Boston, MA

Robert Marra, Community Affairs, Cambridge Health Alliance, Cambridge, MA

Alex Pirie, Immigrant Service Providers Group/Health, Somerville, MA

Mohamed Brahimi, Muslim American Civic and Cultural Association, Malden MA

Margaret English, Institute on Urban Health Research, Bouvé College of Health Sciences; Northeastern University.

Joshua Beckmann, Institute on Urban Health Research, Bouvé College of Health Sciences; Northeastern University.

Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, Institute on Urban Health Research, Bouvé College of Health Sciences; Northeastern University.

Robert P. Marlin, Department of Medicine, Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School

References

- Akram SM, Johnson KR. Race, civil rights, and immigration law after September 11, 2001: The targeting of Arabs and Muslims. NYU Annual Survey American Law. 2001–2003;58:295. [Google Scholar]

- Asch S, Leake B, Anderson R, Gelberg L. Why do symptomatic patients delay obtaining care for tuberculosis? American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;157(4 Pt 1):1244–1248. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9709071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch S, Leake B, Gelberg L. Does fear of immigration authorities deter Tuberculosis patients from seeking care? Western Journal of Medicine. 1994;161(4):373–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk ML, Schur CL. The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2001;3(3):151–156. doi: 10.1023/A:1011389105821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, Castañeda RM, Chaudry A, Santos R. Paying the Price: The impact of immigration Raids on America’s Children. Washington, DC: National Council of La Raza; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano RM. Towards a neighborhood resource-based theory of social capital for health: Can Bourdieu and sociology help? Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda H. Illegality as risk factor: A survey of unauthorized migrant patients in a Berlin clinic. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1552–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Zayas LH, Spitznagel EL. Legal status, emotional well-being and subjective health status of Latino immigrants. Journal of the Natlonal Medical Association. 2007;99(10):1126–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudry A, Capps R, Pedroza JM, Castaneda RM, Santos R, Scott MM U. Institute. Facing our future: Children in the aftermath of immigration enforcement. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton-Mathews A, Karp F, Watanabe P. Massachusetts Immigrants by the Numbers: Demographic Characteristics and Economic Footprint. Malden, MA: The Immigrant Learning Center, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RC, Henderson NJ. Willingness to report crimes: The role of ethnic group membership and community efficacy. Crime & Delinquency. 2003;49:564–580. [Google Scholar]

- Derose KP, Bahney BW, Lurie N, Escarce JJ. Review: immigrants and health care access, quality, and cost. Medical Care Research and Review. 2009;66(4):355–408. doi: 10.1177/1077558708330425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egmont W, Millona E, Chacon R, Tambouret N, Hohn M, Borges-Mendez R. Massachusetts New Americans Agenda. Boston, MA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton JJ, Catalano R, Hargreaves A. Effect Of Proposition 187 On Mental Health Service Use In California: A Case Study. Health Affairs. 1996;15(1):182–190. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.15.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fix M, Tumlin K. Welfare reform and the devolution of immigrant policy Series A. Washington, D.C: The Urban Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Health Safety Net-HSN (Free Care) An Overview. [Accessed 3/11/2011 ];MassResources.org. 2010 http://www.massresources.org/pages.cfm?contentID=50&pageID=13&Subpages=yes.

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241(4865):540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa M, Nakahara S, Wakai S. Effect of post-migration detention on mental health among Afghan asylum seekers in Japan. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40(4):341–346. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulze AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida-Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2002;56(9):647–652. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.9.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller AS, Rosenfeld B, Trinh-Shevrin C, Meserve C, Sachs E, Leviss JA, et al. Mental health of detained asylum seekers. Lancet. 2003;362(9397):1721–1723. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14846-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Bonding versus bridging social capital and their associations with self rated health: a multilevel analysis of 40 US communities. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2006;60(2):116–122. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.038281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: an ecosocial perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):194–199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale DS. Birth outcomes for Arabic-named women in California before and after September 11. Demography. 2007;43(1):185–201. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysakowski M, Pearsall AA, Pope J. Policing in new immigrant communities. U. S. Department of Justice; Washington, D.C: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhaes L, Carrasco C, Gastaldo D. Undocumented migrants in Canada: a scope literature review on health, access to services, and working conditions. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2010;12(1):132–151. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9280-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelli E, Holmes L, Estella D, da Rocha F, Granberry P, Buxton O. (In)Visible (Im)migrants: The health and socioeconomic integration of Brazilians in metropolitan. Boston. San Diego, California: Center for Behavioral and Community Health Studies, San Diego State University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelli E, Holmes L, Troncosco M, Granberry P, Buxton O. Permanently temporary: The health and socioeconomic integration of Dominicans in metropolitan. Boston. San Diego, California: Center for Behavioral and Community Health Studies, San Diego State University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition. New Bedford Immigration raids. Boston, MA: 2010. [Accessed 3/11/2011 ]. http://www.miracoalition.org/home/new-bedford-immigration-raids. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire S, Georges J. Undocumentedness and liminality as health variables. Advances in Nursing Science. 2009;26(3):185–195. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosoical frameworks. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TA. Blurring the boundaries between immigration and crime control after September 11th. Boston College Third World Law Journal. 2005;25(1):1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Fernandez-Kelly PWH. Segmented assimilation on the ground: The new second generation in early adulthood. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2005;28(6):1000–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C, Chishti M, Capps R, StJohn L. A program in flux: New priorities and implementation challenges for 287 (g) Washington, D.C: Migration Policy Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MA, Bustamante AV, Ang A. Perceived quality of care, receipt of preventive care, and usual source of health care among undocumented and other Latinos. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(Suppl 3):508–513. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1098-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Martinez D, Carvajal SC. Bicultural stress and adolescent risk behavriors in a community sample of Latinos and Non-Latino european Americans. Ethnicity and Health. 2007;12(5):443–463. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove D, Steel Z, Mollica RF. Detention of asylum seekers assault on health, human rights, and social development. Lancet. 2001;357:1436–1437. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford M, Chandola T, Marmot M. Association between fear of crime and mental health and physical functioning. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(11):2076–2081. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg N. Policy Analysis Exercise. Boston, MA: The Urban Institute; 2008. Caught in the middle: Undocumented immigrants between federal enforcement and local integration. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Orozco C, Suarez-Orozco MM. Educating Latino immigrant students in the twenty-first century: Principles for the Obama administration. Harvard Educational Review. 2009;79(2):327–340. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SV, Kim DJ, Kawachi I. Social trust and self-rated health in US communities: a multilevel analysis. Journal of Urban Health. 2002;79(4 Suppl 1):S21–34. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.suppl_1.S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suro R. Attitudes about immigration and major demographic characteristics. Washington, D.C: Pew Hispanic Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Torres AM, Sanz B. Health care provision for illegal immigrants: should public health be concerned? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2000;54(6):478–479. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.6.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed 3/11/2011];State and County Quickfacts. 2010 http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/25/2521990.html.

- U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. ICE Fiscal Year 2008 Annual Report. Washington, D.C: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA. Beyond acculturation: Immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(7):1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Schulz AJ. Toward a dynamic conceptualization of social ties and context: implications for understanding immigrant and Latino health. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2167–2175. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/Ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(Supplement 1):S29–S37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.98.supplement_1.s29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray-Lake L, Syvertsen AK, Flanagan CA. Contested Citzenship and social exclusion: Adolescent Arab American immigrants’ views of the social contract. Applied Development Science. 2008;12(2):84–92. [Google Scholar]

- www.Eyewitness News 3. New Haven Approves Immigrant ID Cards. Vol. 3. Hartford, CT: Eyewitness News; 2007. [Accessed 2/11/2011 ]. http://www.wfsb.com/news/13444574/detail.html. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Greenman E. Research Reports. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Population Studies Center, University of Michigan; 2005. Segmented assimilation theory: A reformulation and empirical test. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Segmented assimilation: Issues, controversies, and recent research on the new second generation. International Migration Review. 1997;31(4):975–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]