Abstract

Among 1651 antiretroviral therapy (ART)-eligible patients attending an urban United States HIV clinic, four-year mortality was 10.0% in 2000–2004 and 11.0% in 2005–2009. Despite universal ART availability, only 72 (42%) of 172 patients who died, compared to 69% of survivors, ever achieved an HIV viral load <400 copies/mm3. Leading causes of death were AIDS (56%), violence/overdose (16%), and pulmonary disease (6%). Disadvantaged sub-populations in the developed world can experience high mortality rates despite accessing specialty HIV clinical services with full ART availability. New strategies are needed to improve outcomes in these populations.

Keywords: mortality, HIV, urban health, delivery of health care

Introduction

Over the last decade, new classes of antiretroviral medications and more potent, tolerable drugs have made suppression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) attainable in even extensively treatment-experienced patients.1 Improved clinical outcomes for HIV-infected patients are in large part attributed to these advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART). Among participants across 19 cohort studies of patients initiating ART in Europe and North America, adult life expectancy increased by eight years between 2000 and 2005,2 and less than half of all deaths are now related to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining diagnoses.3 Whether the availability of these options has translated into improved clinical effectiveness among all patient populations – including inner-city populations with a high burden of mental illness, substance abuse and homelessness – is less clear.4,5 Indeed, the studies that examine the actual practice of evidence-based interventions in real-world clinical care (i.e. effectiveness) often reveal heterogeneity in outcomes. We therefore evaluated the effect of recent advances in HIV treatment by examining mortality trends between 2000 and 2009 in a clinic-based cohort of urban uninsured and publicly-insured HIV-infected patients who were successfully linked to outpatient HIV care and eligible for ART.

Methods

Study Population

We evaluated a clinical cohort in a public safety-net HIV specialty clinic in San Francisco, California, USA. All patients were either publicly insured or uninsured, but ART was universally available, regardless of ability to pay. We included consecutive adult (≥18 years) HIV-infected patients enrolled in a larger multi-center cohort6 who had a CD4+ T-cell count nadir of ≤350 cells/mm3 and at least two subsequent primary care visits within any 12-month period from April 1, 2000, to August 31, 2009. Thus, all patients were enrolled at a time when they were eligible for ART by contemporary criteria. Both ART-naïve patients and those with prior ART experience (e.g., transfers from another clinic) were included. Patients were observed until death or study end (August 31, 2009). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Francisco.

Measurement of Study Variables

Baseline characteristics were abstracted from the clinic’s electronic medical record at the time of entry into the cohort (usually the patient’s second primary care clinic visit). We measured the following variables at baseline: age, gender, race, ethnicity, HIV risk factor(s), CD4+ T-cell count, HIV viral load, prior exposure to ART, presence of a mental health diagnosis, alcohol abuse, and hepatitis C status. HIV risk factors were abstracted from historical data recorded during patients’ initial clinical visits. Diagnoses were recorded as International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) codes in medical charts. The dates and values of all CD4+ T-cell counts and viral load measurements obtained after study entry were also abstracted from the medical record. We ascertained mortality by linkage of electronic medical records to the United States Social Security Death Index.

For patients who died, we ascertained the cause of death from chart review using the Cause of Death (CoDe) project protocol (http://www.cphiv.dk/). “Likely AIDS-related” deaths were those due to AIDS-defining illness or non-sudden deaths of unknown etiology in patients with CD4+ T-cell counts <50 cells/mm3. “Possibly AIDS-related” deaths included sudden deaths of unknown cause in patients with CD4+ T-cell counts <50 cells/mm3 and non-sudden deaths of unknown cause in patients with CD4+ T-cell counts between 50 and 199 cells/mm3. Deaths not related to immunodeficiency were classified as due to violence or substance use, lung cancer, liver disease, and all other causes. Causes of death were ascertained by a single physician reviewer (DWD) and verified against data from the National Death Index. Disagreements between initial chart review and the National Death Index were resolved by consensus with a second physician reviewer (KAC).

Statistical Analysis

Our primary analysis was the comparison of mortality rates in 2000–2004 versus 2005–2009. January 1, 2005, was chosen a priori as the midpoint of the analytic frame. We assessed crude mortality rates by the Kaplan-Meier method and performed multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression to evaluate differences in time to death across the two time periods. We evaluated the proportional hazards assumption using visual inspection of –log[-log(survival)] plots and scaled Schoenfeld residuals. All baseline variables were included in multivariable models as categorical variables, with the exceptions of age (continuous), CD4+ T-cell count (non-parametric continuous, plus additional category for <50 cells/mm3), and viral load (continuous on logarithmic scale). Interaction terms with time (2000–2004 vs. 2005–2009) were tested for all variables. Pre-specified secondary analyses included comparison of mortality in five higher-risk sub-groups (injecting drug users, non-white race, female or transgender, alcohol abuse, mental health diagnosis), year-by-year analysis of mortality, and assessment of viral suppression (defined as an HIV viral load <400 copies/mL) at any time during the study period.

Results

A total of 1651 patients were enrolled, of whom 172 (10.4%) died over a median 3.7 (interquartile range IQR, 1.7–5.9) years of follow-up. The population consisted of 1,432 (87%) men and 779 (47%) whites; only 58 patients (3.5%) were white women. Regarding historical HIV risk factors assessed on the initial visit, 981 (59%) patients reported being men who have sex with men (MSM), 408 (25%) injecting drug users (IDU), and 419 (25%) at heterosexual HIV risk. At study entry, the median age was 49 (IQR 43–56), the median CD4+ T-cell count was 205 cells/mm3 (IQR 78–289), and the median HIV viral load was 35,000 copies/mL (IQR 4,700–130,000). ART had been prescribed before study entry for 672 patients (41%), and by study end for 1283 patients (78%). Regarding comorbidities as documented in medical charts, 486 patients (31%) had hepatitis C infection, 664 (40%) a mental illness, and 168 (10%) alcohol abuse. Among patients with a documented mental illness, 348 (52%) had a mood disorder (ICD-9 296 or 311, primarily depression), 151 (23%) had a neurotic disorder (ICD-9 300, primarily anxiety), and 32 (5%) had both.

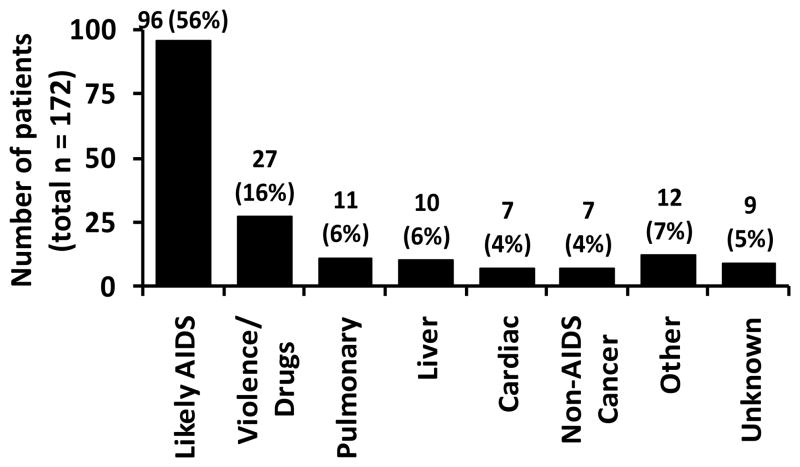

Mean all-cause mortality was 2.65% annually, with no significant year-over-year trend (p=0.27). In the primary analysis, we observed no difference in mortality over 2000–2004, as compared to 2005–2009 (Figure 1; multivariable hazard ratio, HR 1.40; 95% confidence interval, CI: 0.82, 2.39). Baseline variables significantly associated with shorter time to death included younger age (HR 0.72 per 10 years; 95% CI: 0.61, 0.86) and CD4+ T-cell count <50 cells/mm3 (HR 1.79; 95% CI: 1.11, 2.87). Time to death was not associated with prior ART prescription, measured either as a baseline variable at enrollment (adjusted HR 1.24, 95% CI: 0.91, 1.70) or as a time-dependent variable during the study period (HR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.55, 1.36).

Figure 1. Mortality in HIV-infected, ART-eligible patients with two or more primary-care visits to an urban specialty HIV clinic.

The solid line represents the Kaplan-Meier mortality estimate for 2000–2004, and the dotted line represents the estimate for 2005–2009. There was no significant difference in mortality between the two time periods (unadjusted p = 0.34 by log-rank test).

Among all five pre-selected higher-risk subgroups (non-male gender, non-white race, mental illness, alcohol abuse, injecting drug use), adjusted mortality was at least 70% higher (i.e., multivariable HR ≥1.70) in 2005–2009 than in 2000–2004, although this difference was statistically significant only for injecting drug use (HR 4.15; 95% CI: 1.41, 12.2). Crude four-year Kaplan-Meier mortality in injecting drug users was 6.0% (95% CI: 2.1%, 16.5%) in 2000–2004, versus 17.9% (95% CI: 13.7%, 23.3%) in 2005–2009.

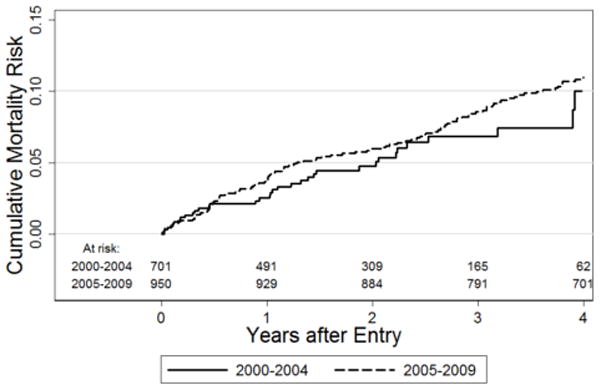

The cause of death was likely AIDS-related in 96 patients (56%) (Figure 2). Over half of non-AIDS related deaths were due either to violence (including suicide) and drug use (27 patients), or smoking-related illness including lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (11 patients). Only 29 deaths (17%) were due to other known causes, primarily liver disease (6%), cardiovascular disease (4%), and non-lung, non-AIDS-related cancer (4%). Causes of death were discordant between initial chart review and National Death Index in 21 patients (12%). Among the 172 patients who died, only 73 (42%) achieved a viral load <400 copies/mL at any point during the study period. Median CD4+ T-cell counts remained statistically unchanged in this group, from 128 cells/mm3 (IQR 33–262) at baseline to 101 cells/mm3 (IQR 29–267) at last measurement before death (p = 0.24 for change). By contrast, among 1479 survivors, 1027 (69%) achieved an undetectable viral load, and median CD4+ T-cell counts increased from 209 cells/mm3 (IQR 87–290) at baseline to 324 cells/mm3 (IQR 188–488) at last measurement (p<0.001).

Figure 2. Causes of Death in HIV-infected, ART-eligible patients attending specialty HIV care.

Violence/drugs includes deaths due to suicide, trauma, and illicit drug use. Pulmonary deaths were due to lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Other causes of death included non-AIDS-related cancer (7), sepsis (2), seizure (1), renal disease (1), and diabetes (1). Among patients with unknown cause of death, 4 (44%) had a CD4 cell count less than 200 cells/mm3.

Discussion

In this cohort of 1,651 patients in an urban safety-net HIV clinic in the United States, mortality was high, largely AIDS-related, and unchanged over the past decade. Four-year mortality was greater than 10%, over twice the mortality rate in representative developed-country cohorts of patients initiating ART.2 In contrast to those cohorts’ recent mortality reductions of over 30%, mortality in this population did not change over the last decade. Mortality was dominated by AIDS-related causes, followed by sequelae of violence and drug use. Despite attending a specialty HIV clinic with universal ART availability at a time when they were ART-eligible, the majority of patients who died never suppressed their viral loads. Advances in the ability of ART to suppress HIV RNA replication have not translated into reduced mortality among this urban, socially-disadvantaged patient population.

Our finding of stable mortality and inadequate viral suppression, despite improvements in HIV care including availability of more potent, tolerable, and co-formulated ART options, demands an explanation. In this urban safety-net population, linkage to specialty HIV care continues to occur late in patients’ disease course (as evidenced by low baseline CD4 count), and access to care alone remains insufficient to avert substantial mortality. The present study was neither designed nor powered to ascertain the specific causes for this phenomenon. However, translation of clinical innovations into patient mortality benefit requires more than drug efficacy,7 and populations with social instability, low health literacy, mistrust of the healthcare system, and mental illness may not benefit from medical advances to the same extent as the general population of people living with HIV/AIDS. Reducing HIV-related mortality in these disadvantaged populations may require more resources to provide structural supports, including stable housing,8 food security,9 services for injecting drug users,10 and appropriate case management.11 Of particular importance is adequate psychiatric care;12 40% of patients had an ICD-9 coded mental illness, and clinical records may greatly underestimate the true burden of both psychiatric disease and substance use. Interventions that enable disadvantaged populations to reap equitable benefits from pharmacological advances must be sought and evaluated, as recommended in the National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States.13 Failure to do so may result in persistently high mortality rates in these populations, as well as a lost opportunity to reduce HIV transmission.14

This study has several limitations. First, by using an observational design, we are unable to assess the causal nature of the associations detected. Second, our ability to ascertain causes of death using national mortality indices and chart review from a single electronic medical record is limited although we did review the charts of all patients who died. Third, as a single-center study, our number of deaths is relatively small (n = 172), although the confidence intervals on our estimates of four-year mortality exclude equivalence with published rates from a large cohort collaboration.1 Fourth, given limited data on medication use, we were unable to assess time-dependent associations between ART adherence and mortality.

In conclusion, we found stable and high (>10% per four years) mortality rates in this population of uninsured or marginally-insured patients who accessed specialty HIV care. Causes of death were dominated by AIDS, violence, and drug use. Most patients who died never suppressed their viral loads, despite being ART-eligible on entry. Access to advanced HIV care alone is insufficient to universally reduce mortality among people living with HIV/AIDS; more intensive attention is needed to populations whose mortality remains high despite linkage to care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and providers of Ward 86, and well as students from the UCSF School of Nursing who performed detailed analyses of mortality in the clinic population leading up to this analysis. An earlier version of this analysis was presented in oral abstract form at AIDS 2010, Vienna, Austria, July 2010.

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers A067039-01A1, MH64384 to J.S.K.]

Footnotes

Presented as an oral abstract at AIDS 2010, Vienna Austria, July 2010

References

- 1.Volberding PA, Deeks SG. Antiretroviral therapy and management of HIV infection. Lancet. 2010;376:49–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372:293–299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Causes of death in HIV-1-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, 1996–2006: collaborative analysis of 13 HIV cohort studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1387–1396. doi: 10.1086/652283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Study Group on Death Rates at High CD4 Count in Antiretroviral Naive Patients. Death rates in HIV-positive antiretroviral-naive patients with CD4 count greater than 350 cells per microL in Europe and North America: a pooled cohort observational study. Lancet. 2010;376:340–345. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60932-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York City. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:397–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitahata MM, Rodriguez B, Haubrich R, et al. Cohort profile: the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:948–955. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss AR, Hahn JA, Perry S, et al. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in the homeless population in San Francisco: a prospective study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1190–1198. doi: 10.1086/424008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kushel MB, Hahn JA, Evans JL, Bangsberg DR, Moss AR. Revolving doors: imprisonment among the homeless and marginally housed population. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1747–1752. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiser SD, Fernandes KA, Brandson EK, et al. The association between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals on HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:342–349. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b627c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimber J, Copeland L, Hickman M, et al. Survival and cessation in injecting drug users: prospective observational study of outcomes and effect of opiate substitution treatment. BMJ. 2010;341:c3172. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushel MB, Colfax G, Ragland K, Heineman A, Palacio H, Bangsberg DR. Case management is associated with improved antiretroviral adherence and CD4+ cell counts in homeless and marginally housed individuals with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:234–242. doi: 10.1086/505212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376:367–387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. Washington, DC: The White House; Jul 13, 2010. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das M, Chu PL, Santos GM, et al. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]