Abstract

Background

Hypercholesterolemia is common in perinatally HIV-infected (HIV+) children, but little is known about the clinical course and management in this population.

Methods

We studied HIV+ children in a multisite prospective cohort study (PACTG 219C) and considered follow-up for two years after development of hypercholesterolemia. We estimated the time to and factors associated with resolution of hypercholesterolemia and described changes in ARV regimen and use of lipid-lowering medications. We defined incident hypercholesterolemia as entry total cholesterol (cholesterol) < 220 mg/dl and two subsequent consecutive cholesterol ≥ 220 mg/dl, and defined resolution of hypercholesterolemia as two consecutive cholesterol < 200 mg/dl after incident hypercholesterolemia.

Results

Among 240 incident hypercholesterolemia cases, 81 (34%) had resolution to normal cholesterol within two years of follow-up (median follow-up = 1.9 years). The median age of cases was 10.3 years with 54% Non-Hispanic black and 53% male. Resolution to normal cholesterol was more likely in children who changed ARV regimen (adjusted Hazard Ratio (aHR) = 2.37, 95%CI 1.45, 3.88) and who were ≥ 13 years old (aHR=2.39, 95%CI 1.33, 4.27). Types of regimen changes varied greatly and 15 children began statins.

Conclusions

The majority of children who develop hypercholesterolemia maintain elevated levels over time, potentially placing them at risk for premature cardiovascular morbidity.

Keywords: HIV, children, hypercholesterolemia, antiretroviral therapy, cohort study

INTRODUCTION

Dyslipidemia is commonly observed in HIV-infected adults and children. Studies in adults show that lipid abnormalities occur early in HIV infection before initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and are characterized by low levels of total cholesterol (total-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)1–4. Elevated triglycerides and very-low density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C) are observed later, especially in those with more advanced disease5. In a study of adult male seroconverters, total-C and LDL-C increased moderately soon after initiation of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) and many subsequently developed elevation of total-C and LDL-C with a low HDL-C4. In other studies initial improvements in total-C and LDL-C following initiation of ARV coincides with restoration of health and a decrease in HIV viral load1–3.

The hyperlipidemia that is widely reported among adults6–8 and children9–14 on HAART may be partly associated with specific classes of ARVs or individual agents. For example, several studies have reported higher total-C levels among children on protease inhibitors (PI)10, 13, 15–19 and specifically with ritonavir use10, 12, 18. In a longitudinal study, HIV-infected children who developed incident hypercholesterolemia were more likely to be receiving boosted or non-boosted PI20. Children treated with a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase (NNRTI) also had higher total-C10,20 in two studies and had higher HDL-C levels15 in another study compared to those not treated with a NNRTI.

As adults and children live longer with HIV, prolonged dyslipidemia may increase the risk of atherosclerotic disease. Thus, there has been much interest in examining whether type of initial therapy or switching ARV may improve lipid profiles and still maintain viral suppression. Switch studies in adults showed improvements in cholesterol with a switch to atazanavir21–23 or raltegravir24, from zidovudine/lamivudine to tenofovir/emtricitabine25 and from stavudine to tenofovir26. Children who switched from PI therapy to a PI-sparing regimen containing nevirapine showed mild decreases in total-C and increases in HDL-C27 as did those who switched from PI to efavirenz28. More studies on the effect of switching ARV are needed in children as newer ARVs, such as atazanavir and darunavir which have an improved lipid profile, are approved in children older than six years of age.

Most perinatally-infected children have not been followed long enough to determine the course and long-term consequences of sustained dyslipidemia or response to therapy. In the general population, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends change in diet and engagement in physical activity as the first step to improve lipid measurements29. They recommend pharmacologic interventions for children with diabetes mellitus or when elevated LDL-C levels persist above a specified cutoff after dietary intervention fails to produce adequate improvement. While several studies show efficacy of lipid-lowering agents in adults with HIV30, 31, the studies in HIV-infected children with dyslipidemia are ongoing and clearly needed to inform guidelines.

Clinical trials have investigated the association between specific antiretrovirals and cholesterol levels in children, but little is known about clinical management of hypercholesterolemia in practice. Tassiopoulos et al. reported an incidence rate of hypercholesterolemia of 3.4 per 100 person-years based on data from the PACTG 219C late outcomes study20. In the current analysis, based on further follow-up of the same PACTG 219C cohort, we followed children after they developed hypercholesterolemia 1) to determine whether their cholesterol levels remained elevated over time, 2) to examine factors associated with reversion to normal cholesterol over two years of follow-up and 3) to describe types of changes in ARV regimens and use of lipid-lowering medications. To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the clinical course and management of hypercholesterolemia in HIV-infected children.

METHODS

Study Population

The Pediatric AIDSClinical Trials Group (PACTG) 219C study is a prospective cohort study designed to examine long-term effects of HIV exposure and antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected and uninfected childrenborn to HIV-infected women. Children enrolled between September 2000 and March 2006 across 89 sites in the United States and Puerto Rico. The last follow-up visit occurred in May 2007. Children were examined at baseline and approximately every 3 months thereafter. At each visit, sociodemographic, clinical and laboratory information were obtained, including clinical diagnoses, start and stop dates of antiretroviral medications, use of concomitant medications, CDC clinical classification, CD4+ T-lymphocyte count and percent (cells/mm3, %), HIV viral loads (copies/ml), height (cm), weight (kg), blood pressure (absolute and percentiles), and other data not included in this analysis. Total cholesterol (mg/dl) was measured at each visit, although fasting was not required. The institutional review board at each participating sites approved the 219C protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from each child’s parent/guardian or from older participants depending on age. Assent was obtained from children as appropriate. This analysis only includes perinatally HIV-infected children.

Definitions of Prevalent and Incident Hypercholesterolemia

We defined hypercholesterolemia as a cholesterol level of ≥ 220 mg/dL (rather than 200 mg/dL) to reduce misclassification, as fasting was not required. Children with prevalent hypercholesterolemia had a total cholesterol ≥ 220mg/dL at the first visit in 219C at which cholesterol was measured. A child had incident hypercholesterolemia if the first measurement of total cholesterol in 219C was < 220 mg/dL and was followed by two consecutive 219C visits of cholesterol ≥ 220 mg/dL at any time during follow-up. Children with no hypercholesterolemia had cholesterol < 220 mg/dL at the first visit and did not have two consecutive visits with total cholesterol ≥ 220 mg/dL.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To study evolution of cholesterol values after hypercholesterolemia, we only included children with at least two additional cholesterol measurements after prevalent or incident hypercholesterolemia and with at least six months of follow-up. Children with no hypercholesterolemia are not included in any analyses, except as a comparison group for describing use of cholesterol-lowering medications/supplements.

Variables Definitions

For the incident hypercholesterolemia group, baseline is the second cholesterol measurement of the pair that defined incident hypercholesterolemia. For the prevalent hypercholesterolemia group baseline is the first cholesterol measurement in 219C. For the following variables we used the baseline measurement as follows: age (< 10, 10–12.9, ≥13 years), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic black, Hispanic/white/other), BMI Z-score (> 1.96 vs. ≤1.96), CD4 percent (<15%, 15–24.9%, ≥ 25%), HIV viral load (≤ 400, > 400–5,000, >5,000 copies/ml). Viral load and CD4 were within 30 days before or 7 days after the cholesterol measure. If BMI Z-score was missing the previous value was carried forward. We calculated percentiles for diastolic and systolic blood pressure for the age, sex, and height of the child based on population norms 32. The percentile for each of the blood pressure measurements was categorized as > 90th percentile vs. ≤ 90th percentile. From concomitant medications recorded for each child, we screened for statins, fibrates, bile acid sequestrants, niacin, and omega-3 fatty acid supplements. The first recorded date of use of a medication/supplement in each group was called the “initiation of use”. We defined reversion to normal cholesterol as two consecutive total cholesterol values <200 mg/dl during follow-up among those with incident hypercholesterolemia.

Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described using the median (25th, 75th percentile) for continuous variables and N (%) for categorical variables. The median (25th, 75th) was computed for cholesterol at six month intervals over the first two years of follow-up. To allow a window period at the 24-month visit after hypercholesterolemia we included records up to 26 months. The percent of children with reported use of lipid-lowering medications including statins, fibrates and/or bile acid sequestrants was determined among those with (prevalent, incident) and without hypercholesterolemia. We determined percent of children who reported ARV at baseline and percent who continued, discontinued, or initiated them at the end of one and two years after incident hypercholesterolemia relative to baseline use.

Time to Reversion of Cholesterol to Normal

We estimated median time to reversion to normal cholesterol over the first two years after incident hypercholesterolemia using a Kaplan-Meier survival estimate. Extended Cox models for time-dependent covariates were used to calculate crude hazard ratios (HR), and hazard ratios adjusted for potential confounders (aHR) for reversion to normal cholesterol over two years. Non-reverters were censored at their last visit (up to 26 months of follow-up). The primary predictors were time-varying covariates 1) any change in ARV regimen; and 2) class of ARV. For each child, we determined any change in ARV regimen. For children who changed regimen, we classified each visit before the regimen change as “no change” (value=0) and the first visit with a changed regimen and all subsequent visits as “changed regimen” (value = 1). If the child did not change regimen all visits were classified as “no change” (value = 0). At each visit, PI, NNRTI, NRTI, and other were categorized as “1” if taking and “0” if not taking medications in each. Use of statins or other lipid-lowering medications was not included as a predictor as too few children received them in the first two years of follow-up and stop dates were ill-defined. Confounders were included in adjusted models if they were independent predictors of the outcome at p < 0.15 or if the log hazard ratio of at least one of the main predictors changed more than 10% when the confounder was in the model. Potential confounders included race/ethnicity, baseline age, BMI and blood pressure and time-varying covariates including CD4% and viral load at the previous visit.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Children at Time of Development of Hypercholesterolemia

There were 2,581 children with at least one cholesterol measurement. Of these, 342 had prevalent hypercholesterolemia, 282 had incident hypercholesterolemia, and 2,239 had no hypercholesterolemia. Our analysis included 314 prevalent cases and 240 incident cases with at least two additional visits and at least six months of follow-up each. Among the 240 children with incident hypercholesterolemia, 218 (91%) had at least one year of follow-up, 213 (89%) had some follow-up in year two, and 182 (76%) had at least two years of follow-up. Characteristics among those with prevalent and incident hypercholesterolemia are in Table 1. The median age was 8.7 years for the prevalent and 10.3 for the incident cases. Approximately half of each group was male and the majority was Non-Hispanic black, similar to characteristics of all enrolled subjects20. Median BMI z-scores were slightly above the age- and sex-adjusted population average for the prevalent (z=0.34) and incident (z=0.28) cohorts. Systolic blood pressure was greater than the 90th percentile for 27% of the prevalent and 23% of the incident groups. HIV viral load was ≤ 400 copies/ml for 64% of the prevalent and 70% of the incident groups. In addition, CD4% was ≥ 25% among 78% and 77% of each group, respectively. Most children (93%) in each group were on a PI-based regimen. Differences in characteristics at the initial cholesterol measurement between those who did and did not develop incident hypercholesterolemia were reported by Tassiopoulos et al20.

Table 1.

Characteristics at the Time of Incident or Prevalent Hypercholesterolemia in HIV-infected Children

| Hypercholesterolemia

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Prevalent (N=314) | Incident (N=240) | |

| Age (yr) | Median | 8.7 (6.1 11.3) | 10.3 (7.5, 12.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | White Non-Hispanic | 61 (19%) | 39 (16%) |

| Black Non-Hispanic | 170 (54%) | 129 (54%) | |

| Hispanic | 79 (25%) | 69 (29%) | |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| Other/unknown | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| More than one race | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Sex | Male | 157 (50%) | 126 (53%) |

| Female | 157 (50%) | 114 (48%) | |

| BMI z-score | Median | 0.34 (−0.31, 0.95) | 0.28 (−0.43, 1.04) |

| Diastolic BP > 90th %-ile | Yes | 32 (10%) | 11 (5%) |

| No | 261 (83%) | 206 (86%) | |

| Missing | 21 (7%) | 23 (10%) | |

| Systolic BP > 90th %-ile | Yes | 86 (27%) | 55 (23%) |

| No | 207 (66%) | 162 (68%) | |

| Missing | 21 (7%) | 23 (10%) | |

| HIV RNA (copies/ml) | 0–400 | 201 (64%) | 169 (70%) |

| 401–5000 | 49 (16%) | 46 (17%) | |

| 5001–50000 | 28 (9%) | 14 (6%) | |

| >50000 | 12 (4%) | 5 (2%) | |

| Missing | 24 (8%) | 11 (5%) | |

| CD4 percent | 0–14% | 16 (5%) | 6 (3%) |

| 15%–24% | 49 (15%) | 39 (16%) | |

| > 25% | 244 (78%) | 185 (77%) | |

| Missing | 6 (2%) | 11 (5%) | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | Median | 242.5 (230, 266) | 236 (227, 251) |

| ARV Class | PI+NRTI(no NNRTI) | 172 (55%) | 132 (55%) |

| PI+NNRTI | 119 (38%) | 90 (38%) | |

| NNRTI+NRTI | 16 (5%) | 7 (3%) | |

| PI only | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | |

| NRTI only | 1 (0%) | 5 (2%) | |

| No ARV | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | |

Use of statins, fibrates, bile acid sequestrants and omega-3 fatty acids are in Table 2. Statins (N=26) were used by more children than bile acid sequestrants (N=9) and fibrates (N=9). Few children reported use of niacin (N=2), omega-3 fatty acids (N=3) or other medications (N=2). Three children with prevalent hypercholesterolemia started statins after entry into 219C (0.9%). Among those with incident hypercholesterolemia, one child (0.4%) started statins before hypercholesterolemia, 15 (5%) started statins after hypercholesterolemia (one of whom had an unknown start date but was assumed to begin after). Seven of 2239 (<1%) children without hypercholesterolemia used statins sometime, all but one of whom began after their baseline cholesterol measure. The median time starting statins after incident hypercholesterolemia was 1.5 yrs (range 0.5 to 4.5). Among 16 incident cases of hypercholesterolemia who used statins, 4 used atorvastatin only, 9 used pravastatin only and 3 started with one of the above statins and then changed to the other. Seven of nine children who used bile acid sequestrants and 4 of 9 who used fibrates did not have hypercholesterolemia by our definition. One child began bile acid sequestrants and another began fibrates before incident hypercholesterolemia, and two children began fibrates after incident hypercholesterolemia. Evaluation of change in ARV regimen relative to use of lipid-lowering medications in the incident cohort revealed that 3 children changed their ARV regimen before and 3 changed after beginning statins and one changed regimen before and one after beginning fibrates, Among those that changed regimen before beginning a lipid-lowering medication, none had started atazanavir or darunavir.

Table 2.

Initiation of Lipid-Lowering Medications/Supplements in Children With and Without Hypercholesterolemia a

| Total | Hypercholesterolemia

|

No high cholesterolb N=(2239) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalent (N=342)c | Incident (N=282)d | |||||

| Medication or Supplement | N | Before Study Entry | After Study Entry | Before Event | After Event | |

| Statins | 26 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 15e | 7 |

| Bile acid sequestrants | 9 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Fibrates | 9 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Niacin | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1f | 1g |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Other medications | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2h |

These data represent the first reported date of use of each of these medications or supplements for each participant

These children did not have prevalent or incident hypercholesterolemia by the definitions used in this study.

This includes all prevalent cases, regardless of duration of follow-up.

This includes all incident cases, regardless of duration of follow-up.

One child was on statins, but the start date was not given. So, we assumed that statins were started after hypercholesterolemia.

The child was on niacin tablets (nicotinic acid)

The child was on niacin as an antilipemic agent

One child was on Clopidogrel bisulfate and one child was on DH-581/probucol

ARV Regimen Changes after Developing Incident Hypercholesterolemia

In the first year after developing hypercholesterolemia, 204 children (85%) did not change their ARV regimen, 27 (11.2%) changed one time, six (2.5%) changed twice, and three (1.2%) changed five or more times (Table 3). Over two years, 64 children (27%) had at least one regimen change. At the end of the first and second years after incident hypercholesterolemia, 1.7% and 4.7% had discontinued PI, 5.0% and 8.4% had discontinued NNRTI and 0.8% and 3.3% had discontinued NRTI, respectively. Few children began atazanavir as it was not labeled for pediatric use during this time. Four of the 6 who began atazanavir were also receiving ritonavir. Of note, for those followed for more than one year, 11 of 136 (8.1%) discontinued ritonavir or ritonavir/lopinavir and 13 of 48 (27%) discontinued efavirenz. Few children switched from stavudine or zidovudine to tenofovir or abacavir.

Table 3.

ARV Used in the First and Second Years of Follow-up Relative to Development of Incident Hypercholesterolemia

| Time Period Relative to Development of Hypercholesterolemia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARV Class | At Development of High Cholesterol | Within first Year a N= 240 | N (%) | Within second year b N=213 | N (%) |

| PI | On PI | Remained on PI | 221 (92.1) | Remained on PI | 191 (90.1) |

| Discontinued all PI | 4 (1.7) | Discontinued all PI | 10 (4.7) | ||

| Not on PI | Not on PI | 13 (5.4) | Not on PI | 8 (3.8) | |

| Started PI | 2 (0.8) | Started PI | 3 (1.4) | ||

| NNRTI | On NNRTI | Remained on NNRTI | 85 (35.4) | Remained on NNRTI | 69 (32.4) |

| Discontinued NNRTI | 12 (5.0) | Discontinued NNRTI | 18 (8.4) | ||

| Not on NNRTI | Not on NNRTI | 140 (58.3) | Not on NNRTI | 120 (56.3) | |

| Started NNRTI | 3 (1.2) | Started NNRTI | 6 (2.8) | ||

| NRTI | On NRTI | Remained on NRTI | 230 (95.8) | Remained on NRTI | 201 (94.4) |

| Discontinued NRTI | 2 (0.8) | Discontinued NRTI | 7 (3.3) | ||

| Not on NRTI | Not on NRTI | 7 (2.9) | Not on NRTI | 4 (1.9) | |

| Started NRTI | 1 (0.4) | Started NRTI | 1 (0.5) | ||

|

| |||||

| Specific ARVc | Not on ATV | Started ATV | 4/236 | Started ATV | 6/213 |

| On Boosted PI | Switched to non-boosted | 2/119 | Switched to non-boosted | 1/104 | |

| Switched to no PI | 4/119 | Switched to no PI | 5/104 | ||

| On Specific PI | Discontinued | Discontinued | |||

| Ritonavir or LPV/r | 6/153 | Ritonavir or LPV/r | 11/136 | ||

| Amprenavir | 2/10 | Amprenavir | 4/7 | ||

| Nelfinavir | 6/72 | Nelfinavir | 11/66 | ||

| Indinavir | 0/11 | Indinavir | 1/10 | ||

| Saquinavir | 1/14 | Saquinavir | 3/13 | ||

| On EFV | Stopped EFV | 10/53 | Stopped EFV | 13/48 | |

| Switched from EFV to NVP | 1/53 | Switched from EFV to NVP | 2/48 | ||

| On EFV + PI | On PI, Dropped EFV | 6/48 | On PI, Dropped EFV | 8/44 | |

| On d4T | Stopped d4T, started TDF or ABC | 3/137 | Stopped d4T, started TDF or ABC | 5/123 | |

| On ZDV | Stopped ZDV, started TDF or ABC | 0/25 | Stopped ZDV, started TDF or ABC | 1/22 | |

| Not on TDF | Started TDF | 5/227 | Started TDF | 18/195 | |

240 children had incident hypercholesterolemia

27 of 240 had follow-up for less than 365 days after hypercholesterolemia and are not counted in the second year

Switches presented are those associated with improvements in cholesterol cited in the literature d Protease inhibitor (PI), Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), tenofovir (TDF), zidovudine (ZDV), abacavir (ABC), atazanavir (ATV), efavirenz (EFV), nevirapine (NVP), lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r)

Reversion to normal cholesterol level

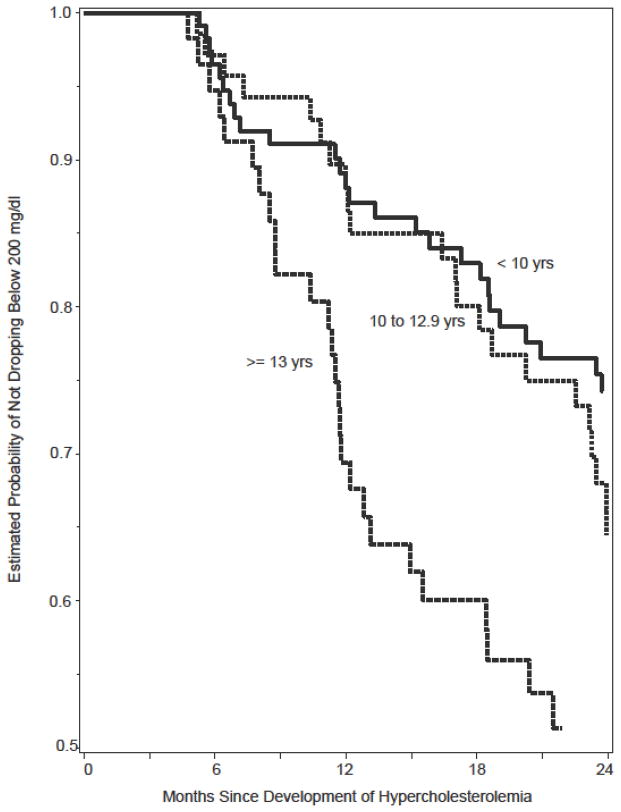

Among the 240 children with incident hypercholesterolemia, 81 (34%) had resolution of their cholesterol to normal levels (< 200 mg/dl on two consecutive visits) within two years of follow-up. Based on a Kaplan-Meier estimate, overall approximately 20% of the 240 were estimated to fall below 200 mg/dl within the first year and 35% below 200 mg/dl after two years. Figure 1 shows the estimated time to reversion to normal cholesterol by age group at baseline among children with incident hypercholesterolemia. Children ≥ 13 years of age had a shorter time to reversion to normal cholesterol. Among the 314 in the prevalent cohort, 98 (31%) had a reversion of their cholesterol to normal levels (on two consecutive visits) where approximately 15% fell below 200 mg/dl within the first year and 29% after two years (not shown).

Figure 1.

Time to Drop in Total Cholesterol Below 200 mg/dl Over

Two Years of Follow-up by Age (yrs) at Time of Hypercholesterolemia

In Cox models, children 13 years and older (aHR=2.4, 95% CI 1.3, 4.3) were more likely to revert to normal cholesterol over two years (Table 4) as were children who had any change in ARV regimen (aHR=2.4, 95% CI 1.5, 3.9). The adjusted hazard ratio did not change with additional adjustment for viral load. However, children with viral load > 5,000 copies/ml were more likely to revert to normal cholesterol over two years (aHR=2.7, 95% CI 1.4, 4.9). Class of ARV was not independently predictive of a drop in cholesterol to < 200 mg/dl and not included in the adjusted models. In univariate models, children on efavirenz were less likely to have a reversion to normal cholesterol while tenofovir users were more likely to drop to < 200 mg/dl. However, we had limited power to evaluate individual ARV agents in adjusted models and thus they are not presented. In a separate Cox regression analysis examining predictors of change in ARV regimen, those with detectable HIV viral load were 2.9 times (95%CI 1.78, 4.78, p<0.001) more likely to change regimen, but cholesterol level was not predictive of regimen change (aHR =1.003, 95%CI 0.998, 1.008), p=0.30), after adjustment for age.

Table 4.

Predictors of Reversion to Total Cholesterol to < 200 mg/dl within Two Years After Incident Hypercholesterolemia

| Characteristic | Unadjusted Models | Adjusted Models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (without RNA) (N=226) | Model 2 (with RNA) (N=217) a | |||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | aHR (95% CI) | P value | aHR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Change in ARV regimen (yes vs. no) | 2.87 (1.79, 4.59) | <0.001 | 2.37 (1.45, 3.88) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.21. 3.33) | 0.01 |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |||

| ≥13 vs < 10 | 3.07 (1.76, 5.38) | 2.39 (1.33, 4.27) | 2.31 (1.28, 4.16) | |||

| 10–12 vs < 10 | 1.56 (0.87, 2.80) | 1.32 (0.73, 2.39) | 1.28 (0.70, 2.35) | |||

| HIV copies/ml (vs. ≤400) | <0.001 | 0.01 | ||||

| >5,000 | 3.11 (1.70, 5.69) | 2.66 (1.42, 4.90) | ||||

| 401 –5,000 | 1.62 (0.86, 3.04) | 1.44 (0.76, 2.72) | ||||

| Male vs. Female | 0.92 (0.58, 1.50) | 0.72 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black vs. | 0.96 (0.61, 1.53) | 0.88 | ||||

| Hispanic/White/other | ||||||

| Systolic BP > 90th Percentile | 0.86 (0.52, 1.44) | 0.58 | ||||

| Diastolic BP> 90th Percentile | 0.72 0.29, 1.80) | 0.48 | ||||

| BMI z- score > 1.96 | 0.56 (0.18, 1.80) | 0.33 | ||||

| CD4 %b | 0.11 | |||||

| < 15 vs. > 25% | 1.03 (0.14, 7.45) | |||||

| 15–24% vs. > 25% | 1.89 (1.04, 3.41) | |||||

| ARV class c | ||||||

| Current PI (yes vs. no) | 0.81 (0.34, 1.88) | 0.62 | ||||

| Current NNRTI (yes vs. no) | 0.55 (0.32, 0.95) | 0.03 | ||||

| Current NRTI (yes vs. no) | 0.49 (0.18, 1.29) | 0.15 | ||||

The total number of children evaluated in this model is lower because some children did not have a viral load measure that was within 30 days before or 7 days after the cholesterol measure.

This is a time-varying covariate;

Indicators for current PI, NNRTI and NRTI use included together in the same model.

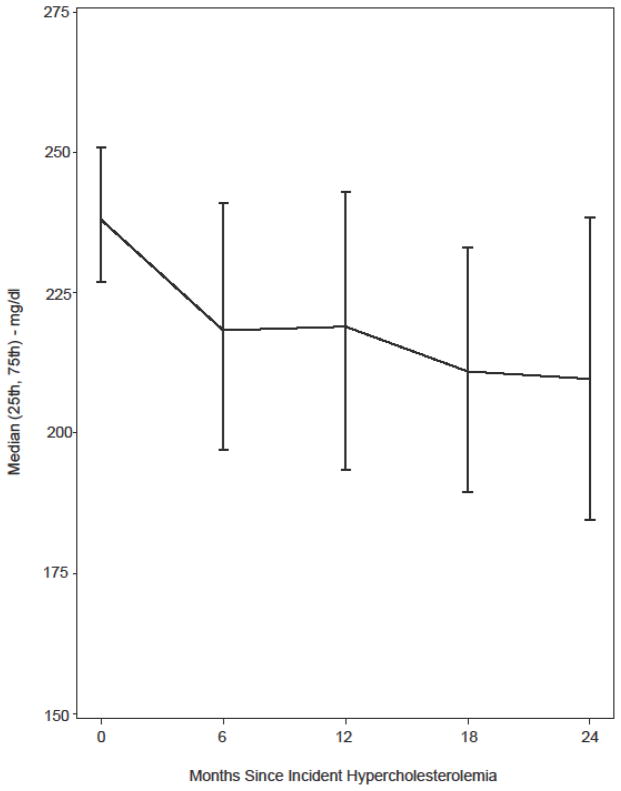

Figure 2 shows the evolution of cholesterol levels over two years of follow-up by six-month intervals. The median cholesterol level dropped from 236 mg/dl at the time of hypercholesterolemia to 217 mg/dl six months later. It was 220, 210 and 206 mg/dl at the 12-month, 18-month and 24-month visit, respectively. Among children in our cohort who changed regimen, the average decrease in cholesterol was 22 mg/dl from the visit prior to regimen change until a median of 7 months after the regimen change.

Figure 2.

Evolution of Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) Within Two Years After Incident Hypercholesterolemia

DISCUSSION

The high prevalence10 and incidence of hypercholesterolemia20 previously reported in this cohort of perinatally HIV-infected children and in other studies of children 9–14 raises concern about the long-term risk of cardiovascular morbidity in HIV-infected children as they age into adulthood. There is a paucity of information on the course of hypercholesterolemia over time in HIV-infected children and the factors associated with resolution of hypercholesterolemia. In this current analysis, the majority of children with incident hypercholesterolemia failed to demonstrate resolution of elevated cholesterol levels over two years of follow-up. The median cholesterol level decreased from 236 to 220 mg/dl in the first year, and only 20% of the children with incident hypercholesterolemia had a resolution to levels below 200 mg/dl within the first year and 35% by the second year of follow-up. While guidelines exist for statin use in children without HIV29 and studies are now ongoing on use of lipid-lowering medications in HIV-infected children, there are no published guidelines about what lipid levels should prompt pharmacologic intervention in HIV-infected children. As a likely consequence, only a small percentage of children initiated statins after developing hypercholesterolemia in our study, and the median time to initiation of treatment was 2.5 years after development of hypercholesterolemia.

Elevated total and LDL cholesterol and lower HDL cholesterol have been associated with protease inhibitors,10, 13, 15–19 especially ritonavir10, 12, 18, NNRTIs10 and some NRTIs in HIV-infected children. Previous work in this cohort also found that children on PIs, boosted or non-boosted with ritonavir, were more likely to develop hypercholesterolemia20. As previously mentioned, numerous switch studies were performed in adults to evaluate whether lipid levels could be improved by substituting an ARV with a less atherogenic profile, while few were done in children21–28, 33. To more fully understand management of hypercholesterolemia among HIV-infected children in this study, we evaluated types of changes in ARV regimens after incident hypercholesterolemia, focusing on changes that have been studied in clinical trials. While any change in ARV therapy after incident hypercholesterolemia was associated with decline in cholesterol to normal values, regimen changes varied greatly from single to multiple drug substitutions, showing no distinct pattern. Twenty-seven percent of children with incident hypercholesterolemia made at least one change in their ARV regimen over two years, but few children made the type of switches that were shown to be beneficial from clinical trials conducted in adults. Of all ARV regimen changes, the most prevalent was discontinuation of efavirenz.

Change in ARV regimen was associated with a decrease in cholesterol, but it is difficult to attribute the decrease to a specific class or agent in this cohort. We lacked power to detect differences in individual medications as changes in medication ranged from single substitutions to a complete change in regimen and the majority of patients remained on PI. In addition to evaluating the types of changes in ARV we also studied the magnitude of change in cholesterol after changing regimen. In studies where patients were switched to tenofovir, the magnitude of effect on total cholesterol ranged from a 4 to 18 mg/dl decrease22, 25, 26. Among children in our cohort who changed regimen, the average change in cholesterol was 22 mg/dl. Although regimen change was associated with decreased cholesterol our analysis of predictors of regimen change showed that uncontrolled viral load and not hypercholesterolemia predicted change in ARV. High viral load may reflect non-adherence. Further studies are needed to understand the effect of specific regimen changes on cholesterol and to carefully control for the potential effects of disease severity, immune activation and diet on cholesterol. In our cohort, children 13 and older were more likely to revert to normal cholesterol. This may be partially explained by data from NHANES which showed that mean cholesterol levels peak at ages 9–11 and then decline in older children34. Children over 13 years old were also more likely to change ARV regimen, perhaps because they have more treatment options or are less adherent to ARV, as shown previously in the 219C cohort35. Poorer adherence could reduce exposure to deleterious effects of specific ARV, including hypercholesterolemia as shown by Tassiopoulos et al. in the examination of risk factors for developing hypercholesterolemia in the 219C cohort20.

HIV-infected adults with dyslipidemia have benefited from statin use30, 31. Clinical trials of statins in infected children began after 219C was complete. This may explain why few children in our cohort were known to have begun statin therapy after incident hypercholesterolemia. We were unable to determine the effect of statins on cholesterol levels as we did not have enough follow-up cholesterol values after children began statins. We also did not have enough information to determine how long statins were taken and if the children were adherent. Statin use was also reported by children with prevalent hypercholesterolemia and by children who did not fit our definition of hypercholesterolemia. In addition, other lipid-lowering medications were used by children in 219C to treat other types of dyslipidemia. However, we do not have information on fasting LDL or HDL cholesterol or triglycerides to determine if these lipid components were abnormal. The current guidelines for treating dyslipidemia recommend change in diet and increase in physical activity as first line therapy 29 which we did not collect, thus precluding assessment of compliance and benefit. Future studies will benefit from data on diet and exercise to better understand their effectiveness and provide recommendations and practice regarding dyslipidemia.

To our knowledge, few studies have addressed management of children with hypercholesterolemia. We characterized clinical management of these children with available data, evaluated evolution of cholesterol over time and factors associated with resolution to normal levels. Future studies should monitor changes in LDL and HDL cholesterol and triglycerides over time in response to improvements in diet and exercise, newer ARV medications and lipid-lowering medications. It is important to understand the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease among HIV-infected children as they progress to adulthood to develop safe preventive measures.

Acknowledgments

We thank the children and families for their participation in PACTG 219C, and the individuals and institutions involved in the conduct of 219C as well as the leadership and participants of the P219/219C protocol team. Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [U01 AI068632], the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) [AI068632]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at Harvard School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement #5 U01 AI41110 with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) and #1 U01 AI068616 with the IMPAACT Group. Support of the sites was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C). We also thank the individual staff members and sites who have participated in the conduct of this study, as provided in Appendix 1.

We thank Todd Brown, MD PhD, for clinical information used to develop this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Grunfeld C, Pang M, Doerrler W, et al. Lipids, lipoproteins, triglyceride clearance, and cytokines in human immunodeficiency virus infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:1045–52. doi: 10.1210/jcem.74.5.1373735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.EL-Sadr WM, Mullin CM, Carr A, et al. Effects of HIV disease on lipid, glucose and insulin levels: results from a large antiretroviral-naive cohort. HIV Medicine. 2005;6:114–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Constans J, Pellegrin JL, Peuchant E, et al. Plasma lipids in HIV-infected patients: a prospective study in 95 patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 1994;24:416–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1994.tb02185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riddler SA, Smit E, Cole SR, et al. Impact of HIV infection and HAART on serum lipids in men. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:2978–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunfeld C, Kotler DPSJK, Doerrler W, et al. Circulating interfereon-alpha levels and hypertriglyceridemia in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1991;90:154–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr A, Samaras K, Burton S, et al. A syndrome of peripheral lipodystrophy, hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitors. AIDS. 1998;12:F51–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulligan K. Abnormalities of body composition and lipids associated with HAART: nPathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and case definitions. 7th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2000. p. S20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulligan K, Grunfeld C, Tai VW, et al. Hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance are induced by protease inhibitors independent of changes in body composition in patients with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23:35–43. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200001010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melvin AJ, Lennon S, Mohan KM, et al. Metabolic abnormalities in HIV type 1-infected children treated and not treated with protease inhibitors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:1117–23. doi: 10.1089/088922201316912727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farley J, Gona P, Crain M, et al. Prevalence of elevated cholesterol and associated risk factors among perinatally HIV-infected children (4–19 years old) in Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 219C. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:480–7. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000139397.30612.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lainka E, Oezbek S, Falck M, et al. Marked dyslipidemia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children on protease inhibitor-containing antiretroviral therapy. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e56. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Paediatric Lipodystrophy Group. Antiretroviral therapy, fat redistribution and hyperlipidaemia in HIV-infected children in Europe. AIDS. 2004;18:1443–51. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131334.38172.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bitnun A, Sochett E, Babyn P, et al. Serum lipids, glucose homeostasis and abdominal adipose tissue distribution in protease inhibitor-treated and naive HIV-infected children. AIDS. 2003;17:1319–27. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200306130-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhoads MP, Smith CJ, Tudor-Williams G, et al. Effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy on paediatric metabolite levels. HIV Med. 2006;7:16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller TL, Orav EJ, Lipshultz SE, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus-1. J Pediatr. 2008;153:491–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter RJ, Wiener J, Abrams EJ, et al. Dyslipidemia among perinatally HIV-infected children enrolled in the PACTS-HOPE cohort, 1999–2004: a longitudinal analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:453–60. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000218344.88304.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Periard D, Telenti A, Sudre P, et al. Atherogenic dyslipidemia in HIV-infected individuals treated with protease inhibitors. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Circulation. 1999;100:700–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.7.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheseaux JJ, Jotterand V, Aebi C, et al. Hyperlipidemia in HIV-infected children treated with protease inhibitors: relevance for cardiovascular diseases. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:288–93. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200207010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chantry CJ, Hughes MD, Alvero C, et al. Lipid and glucose alterations in HIV-infected children beginning or changing antiretroviral therapy. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e129–38. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tassiopoulos K, Williams PL, Seage GR, 3rd, et al. Association of Hypercholesterolemia Incidence With Antiretroviral Treatment, Including Protease Inhibitors, Among Perinatally HIV-Infected Children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:607–14. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181648e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flammer AJ, Vo NT, Ledergerber B, et al. Effect of atazanavir versus other protease inhibitor-containing antiretroviral therapy on endothelial function in HIV-infected persons: randomised controlled trial. Heart. 2009;95:385–90. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.137646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sension M, Andrade Neto JL, Grinsztejn B, et al. Improvement in lipid profiles in antiretroviral-experienced HIV-positive patients with hyperlipidemia after a switch to unboosted atazanavir. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:153–62. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a5701c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colafigli M, Di Giambenedetto S, Bracciale L, et al. Cardiovascular risk score change in HIV-1-infected patients switched to an atazanavir-based combination antiretroviral regimen. HIV Med. 2008;9:172–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eron JJ, Young B, Cooper DA, et al. Switch to a raltegravir-based regimen versus continuation of a lopinavir-ritonavir-based regimen in stable HIV-infected patients with suppressed viraemia (SWITCHMRK 1 and 2): two multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;375:396–407. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher M, Moyle GJ, Shahmanesh M, et al. A randomized comparative trial of continued zidovudine/lamivudine or replacement with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine in efavirenz-treated HIV-1-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:562–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ae2eb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Llibre JM, Domingo P, Palacios R, et al. Sustained improvement of dyslipidaemia in HAART-treated patients replacing stavudine with tenofovir. AIDS. 2006;20:1407–14. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233574.49220.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez-Tome MI, Amador JT, Pena MJ, et al. Outcome of protease inhibitor substitution with nevirapine in HIV-1 infected children. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McComsey G, Bhumbra N, Ma JF, et al. Impact of protease inhibitor substitution with efavirenz in HIV-infected children: results of the First Pediatric Switch Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e275–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.e275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniels SR, Greer FR Committee on Nutrition. Lipid screening and cardiovascular health in childhood. Pediatrics. 2008;122:198–208. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aberg JA, Zackin RA, Brobst SW, et al. A randomized trial of the efficacy and safety of fenofibrate versus pravastatin in HIV-infected subjects with lipid abnormalities: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 5087. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21:757–67. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calza L, Manfredi R, Colangeli V, et al. Rosuvastatin, pravastatin, and atorvastatin for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia in HIV-infected patients receiving protease inhibitors. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6:572–8. doi: 10.2174/157016208786501481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vigano A, Aldrovandi GM, Giacomet V, et al. Improvement in dyslipidaemia after switching stavudine to tenofovir and replacing protease inhibitors with efavirenz in HIV-infected children. Antivir Ther. 2005;10:917–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hickman TB, Briefel RR, Carroll MD, et al. Distributions and trends of serum lipid levels among United States children and adolescents ages 4–19 years: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prev Med. 1998;27:879–90. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams PL, Storm D, Montepiedra G, et al. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1745–57. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]