Abstract

Previous studies have shown that adult female rats consume more ethanol than adult males. Castration of male rats has been found to increase their ethanol intake and preference to levels significantly elevated above their sham-gonadectomized counterparts and similar to levels observed in females. The purpose of the present experiment was to examine whether testosterone replacement in castrated adult male rats would be sufficient to restore the relatively low levels of ethanol drinking characteristic of intact adult male rats. Males were either gonadectomized and implanted with a testosterone propionate pellet (RPL), gonadectomized and implanted with a placebo pellet (GX), sham-gonadectomized and implanted with a placebo pellet (SH), or were left non-manipulated (NM). Voluntary ethanol intake was measured using a 2 hr limited-access drinking paradigm, with access to two bottles: one containing water, and the other a sweetened ethanol solution. Hormone replacement was sufficient to return ethanol intake and preference of castrates to levels comparable to both SH and NM control males. Ethanol preference of RPL males was also significantly suppressed compared to GX males by the end of the measurement period, whereas these group comparisons did not reach statistical significance for g/kg ethanol intake. These data suggest that testosterone serves to suppress ethanol preference in male rats, and may contribute to the sex differences in ethanol preference and consumption commonly reported in adult rats.

Keywords: ethanol intake, gonadal hormones, testosterone, gonadectomy, male, rat

Prior research examining alcohol intake, sensitivity, and responsivity has focused primarily on males, although sex differences in alcohol consumption and sensitivity are present in both humans and laboratory animals. Sexually dimorphic patterns of alcohol consumption have been consistently observed among humans [36]. These differences between men and women appear to become more pronounced in adulthood, with men generally consuming more drinks per occasion than women [7], although women show increased vulnerability to health-related consequences of alcohol consumption, and may therefore be more sensitive to ethanol in this respect [14].

In laboratory rodents, the sexually dimorphic intake pattern is characterized by greater g/kg ethanol intake among adult females than males [8, 10, 23, 25, 42, 35]. This sex-typical ethanol consumption pattern may be influenced, in part, by the presence of gonadal hormones, particularly in males. For instance, a recent study conducted in our laboratory found that both pre-pubertal and adult gonadectomy in males resulted in levels of ethanol consumption and preference in adulthood that were elevated above those of sham-gonadectomized males and similar to those of adult females, suggesting a potential suppressant role for testosterone in lowering ethanol intake in males, and contributing to the sex differences typically seen in this behavior in adult rats [41]. Similar effects of gonadectomy in males were recently reported by another group, with elevated ethanol intake among male rats castrated prior to puberty [34]. Taken together, these results are consistent with an “activational” rather than “organizational” influence of testosterone and/or testicular hormones on ethanol intake, with the presence of these gonadal substances in gonadally intact males seemingly serving to moderate their ethanol intake.

Nevertheless, several previous studies examining the impact of castration on ethanol consumption in male rats and mice have reported either no difference between gonadectomized and intact males [2, 6, 17] or a gonadectomy-associated decrease in ethanol drinking under certain housing conditions [3], with this latter effect contrary to the findings of our laboratory and others [41, 34]. Daily dihydrotestosterone treatment was found, however, to decrease ethanol consumption in both castrates and intact males, findings that support a possible suppressive effect of testosterone on ethanol drinking in males [2]. It is possible that methodological differences such as housing condition, drinking paradigm or deprivation status could explain the varying effects of castration found across studies.

Since the gonadectomy data from our laboratory support a possible role of testosterone or other testicular hormones in suppressing ethanol intake [41], the present experiment examined whether testosterone replacement in castrated adult males would be sufficient to restore these animals to the relatively low levels of ethanol drinking characteristic of intact adult male rats. If increased ethanol consumption among castrated adult males is the result of the removal of a suppressant effect of testosterone on ethanol intake, then the restoration of testosterone to physiologically relevant levels in these animals should reduce their ethanol intake and preference to levels similar to those displayed by their sham counterparts.

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats bred in our colony at Binghamton University and pair-housed at weaning were used in this study. Animals were treated in accordance with guidelines for animal care established by the National Institutes of Health [18], using protocols approved by the Binghamton University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Throughout this experiment, no more than one animal per litter was assigned to any given experimental condition.

A total of 32 males, 8 per experimental group, were used in this study. One group was gonadectomized and subsequently underwent hormonal replacement via implantation with a testosterone propionate pellet (RPL). A second group was similarly gonadectomized but was then implanted with a placebo pellet (GX). A third group received a sham-gonadectomy surgery followed by replacement with a placebo pellet (SH). As a control for surgically manipulated sham animals, an additional non-manipulated (NM) control group of adult males was also included. Animals in all groups were re-housed with a male non-littermate of the same age and assigned to the same experimental condition on P68, two days prior to surgery for animals in the RPL, GX and SH group.

On P70, males were either gonadectomized or sham-gonadectomized using the same methods previously described [see 41]. One week later (on P77), each animal was implanted with either a testosterone-containing or placebo pellet. For the RPL group, a 21-day release 5 mg testosterone propionate (TP) pellet (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL) was implanted at the base of the neck on the dorsal side of the animal. This dose of TP was chosen based on data from a pilot study conducted in our laboratory, the results of which showed that implantation of a 5 mg testosterone propionate pellet in GX males during early adulthood resulted in mean circulating plasma testosterone levels similar to those of intact, sexually naïve males of the same age. Animals assigned to the GX and SH groups were similarly implanted with a placebo pellet of the same size (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL). For three days following gonadectomy/sham-gonadectomy and for one day following pellet implantation, animals were separated from their housing partner by a wire-mesh divider in the home cage to avoid perturbation of the wound sites.

Ethanol intake testing for all animals began on P82. Animals were water deprived for 24 hrs prior to the first 2-hr limited-access intake session. On each test day, animals were weighed and each housing pair was separated in the home cage by a mesh divider from 15 min prior to until 15 min after the intake session, thereby allowing separate assessment of the ethanol consumption of each animal. During the 2-hr limited-access sessions, each animal was given access to two bottles: one containing tap water and the other a sweetened (0.1% saccharin) ethanol solution, with the positions alternated across days. Using the same procedure as was previously employed [41], animals were initiated to drinking through exposure to a 6% ethanol solution on experimental days 1–4 prior to intake testing at a concentration of 10% on experimental days 5–12. Approximately 30 min after testing, each pair of animals received a supplemental water allocation (generally ranging from 25–30 ml per cage) to maintain weight trajectories that were approximately 85% that of non-deprived animals of the corresponding age, sex and surgical group. To accomplish this goal, pre-intake body weights were taken daily, with the amount of supplementary water provided adjusted daily (by 1–2 ml as necessary) to meet target body weight trajectories for each animal (see [41] for a full description of the water deprivation procedure). All ethanol intake testing was conducted between 1300 and 1600 hrs.

Blood samples from the tail were collected immediately following the 2-hr access session half-way through ethanol intake testing (i.e. on day 6) for analysis of blood ethanol concentrations (BECs). Trunk blood was collected after the last intake session (day 12) for analysis of BEC and testosterone levels. Whole blood for BEC analyses and plasma for hormone assays were stored at −80° C until the time of assay.

BECs were determined via gas chromatography, using a Hewlett Packard (HP; Palo Alto, CA) 5890 series II Gas Chromatograph, a HP 7694E Headspace Sampler, and HP Chemstation software [33]. For analysis of testosterone, plasma samples were thawed, and unbound levels of the hormone were assessed via radioimmunoassay using a Packard Cobra II Autogamma Counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and a 125I RIA double antibody kit from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH), with an assay specificity of 100%, an assay sensitivity of 0.03 ng/ml, and inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation of 10.1% and 6.6%, respectively.

Prior to analysis, Levene’s tests were used to assess homogeneity of variance (HV) within each data set, with non-parametric statistics used in instances of significant non-HV as described further below. Due to variability in intake measures across days, intake and preference data were combined into 2-day blocks and analyzed separately at each ethanol concentration using 4 group (RPL; GX; SH; NM) × block repeated measures ANOVAs, with 2 levels of block at the 6% concentration and 4 levels of block at the 10% concentration. Ethanol preference scores were calculated via the formula: (ml ethanol solution intake)/ (ml ethanol solution intake + ml water intake). Day 6 & 12 BEC data were analyzed across group using separate one-way ANOVAs. Fisher’s LSD tests were used to determine the locus of significant main effects and interactions in the ANOVAs. This post-hoc test was chosen based on its ability to detect reliable differences between means while maintaining reasonable protection against Type I errors [9].

The analysis of ethanol intake data across the 2 intake blocks at the 6% ethanol concentration revealed no significant effects of group or block (data not shown). Analysis of preference scores at the 6% concentration revealed a significant main effect of block (F(3, 28) = 7.31, p< .05) and an interaction between group and block (F(2, 28) = 3.19, p< .05), with preference (mean ± SEM) of GX males increasing significantly from block 1 (0.09 ± 0.04) to 2 (0.18 ± 0.05) and differing significantly from that of SH males during the 2nd block (0.06 ± 0.03).

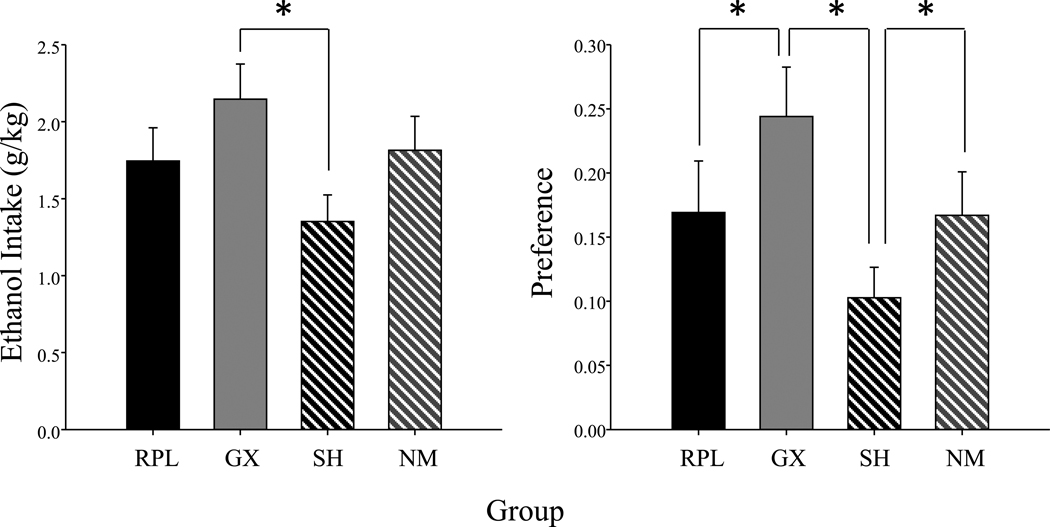

At the 10% ethanol concentration, a main effect of group (F(3, 28) = 3.33, p< .05) emerged in the ANOVA of ethanol intake, with GX males drinking significantly more ethanol than SH males, whereas levels of intake of RPL & NM males were intermediate and did not significantly differ from either GX or SH males (see Figure 1 for data collapsed across block). A main effect of group (F(3, 28) = 4.34, p< .01) emerged in the analysis of preference scores at the 10% concentration, with GX males having significantly greater preference scores than both SH and RPL males. Additionally, preference of SH males was significantly lower than that of NM males (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean ethanol intake (g/kg) and preference scores of gonadectomized and testosterone propionate replaced (RPL; n=8), gonadectomized and placebo replaced (GX; n=8), sham-gonadectomized and placebo replaced (SH; n=8) and non-manipulated (NM; n=8) males are shown collapsed across the four 2-day blocks of the 10% ethanol concentration. The * symbol represents significant differences between the groups indicated and the bars represent standard error.

No significant effects emerged in the analysis of BECs (tail blood) on day 6. In the analysis of BECs (trunk blood) taken at the end of the 2 hr intake session on day 12, there was a significant main effect of group (F(3,28) = 4.67, p< .01), with GX males (32.03 ± 9.85) displaying significantly higher BECs (mg/dl) than males in the NM (2.16 ± 1.77) and SH (2.34 ± 2.11) groups, and with a similar trend seen in RPL males as well (15.44 ± 8.14). According to the Levene’s test, plasma testosterone data violated the assumption of HV and, therefore, were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis H test followed by Mann-Whitney U tests to further analyze the locus of significant group differences. This analysis revealed significant differences in circulating plasma testosterone levels (ng/ml) between the groups (H(3) = 18.06, p< .01), with levels among GX animals (0.00 ± 0.00) significantly lower than the RPL (0.74 ±0.14), SH (0.64 ± 0.10), and NM (0.83 ± 0.21) males, and with the latter groups not differing significantly from each other.

The results of this study confirm previous findings in our laboratory showing that ethanol intake and preference data are elevated in GX relative to SH male rats [41], an effect that, in the current study, was particularly pronounced at the 10% ethanol concentration. Replacement of testosterone via pellet implantation was found to result in levels of ethanol intake and preference scores in castrated males that were intermediate and not significantly different from gonadally intact SH and NM males. Hormone replacement was not, however, sufficient to significantly suppress ethanol intake compared to that of GX males at either concentration, although, preference scores of RPL males were significantly lower than those of GX males at the 10% ethanol concentration. Thus, hormone replacement was generally sufficient to return drinking behavior of castrated animals to levels that were comparable to gonadally intact SH and NM males, although not to levels significantly lower than GX males on the ethanol intake measure. These data support a modulatory role for testosterone in suppressing ethanol consumption in male rats that likely contributes to the sex differences in ethanol consumption/preference that are typically observed in adult rats [10, 42].

While statistical comparisons across studies are not possible, the relative differences between ethanol intake levels of GX and SH groups in the current study are similar to those previously observed in our laboratory [41], although the overall ethanol intake levels (mean ± SEM) of GX (2.14 g/kg ± 0.18) and SH (1.35 g/kg ± 0.21) males at the 10% ethanol concentration in the current study were slightly higher than in that study (GX (1.42 g/kg ± 0.13); SH (0.85 g/kg ± 0.19)). Differences in overall consumption levels across experiments do vary somewhat, likely due to the variations in experimenter, season and procedural differences between studies (such as the double surgical manipulation animals received in the current study).

The generally intermediate levels of ethanol intake seen in RPL males when compared with GX versus SH and NM males does not appear to be related to the dose of the replacement hormone that was used, given that there were no differences in testosterone levels between RPL males and their SH and NM counterparts. It is also possible that ethanol intake of RPL males was not significantly suppressed compared to GX males because testosterone replacement was able to mimic, but not completely replicate the hormonal environment induced by the intact testes. For example, hormone production by the testes is not limited to testosterone, with the testes also producing androstenedione [40] as well as peptide hormones such as inhibin [5] and insulin-like growth factor [38]. The role of these other testicular-derived products in behaviors associated with ethanol consumption has not been thoroughly investigated, but these hormones could potentially influence behavior in intact males in ways that are not mimicked by mere restoration of testosterone levels alone in castrated males. Similarly, replacement of testosterone via the pellet delivery system also does not completely mimic the pattern of hormone exposure experienced by the intact male. For example, several studies have found evidence for diurnal fluctuations in plasma testosterone in male rats [29, 20, 21, 24], although the timing of these peaks and troughs has been found to differ widely across studies, with some reporting elevations during the light cycle around mid-day and at the onset of the dark cycle [29], whereas others have found mid-afternoon peaks as well as troughs at the onset of the dark cycle [24]. Although it is currently unknown how these diurnal variations in testosterone influence ethanol intake, it is possible that the patterns of ethanol intake observed among SH and NM males may be influenced by these hormonal fluctuations in a way not mimicked by pellet hormone replacement.

Significant differences in ethanol intake among the experimental groups were reflected in the analyses of blood ethanol concentrations on day 12, but not on day 6, with GX males displaying significantly higher BECs than SH and NM males, and RPL males not significantly different from either group. Differences in the type of blood sample (i.e. tail vein vs. trunk) used for these analyses may have contributed to the lack of differences between groups on day 6. Indeed, a previous study comparing BECs in blood samples collected from the tail vein, carotid artery, jugular or femoral vein after ethanol administration showed that ethanol concentrations in blood collected from the tail vein were markedly lower than those of blood collected from the other sources, possibly due to low blood perfusion to tissue water ratio in the tail [26]. Thus, tail vein blood samples may underestimate circulating levels of ethanol in blood, whereas ethanol levels derived from trunk blood may be more representative of circulating BECs. In general, although BECs on day 12 in GX males were within the moderately intoxicating range of 20–90 mg/dl [see 12], they were lower than one might have expected based on ethanol intake levels [41]. This effect could be due to the pattern of ethanol consumption across 2 hr access sessions. Indeed, in prior work, animals have been reported to drink most of their ethanol during the first 15–30 min of intake sessions [4] – leading to early peaks in BEC, along with relatively modest BECs by the conclusion of 2 hr access periods.

Unlike the results of the present study in male rats, which suggest that testosterone may act to suppress ethanol intake, correlational studies in humans generally suggest that higher testosterone levels in males are associated with greater ethanol consumption. Among college-age men, studies have found that testosterone levels were positively correlated with alcohol consumption [22] as well as blood alcohol concentration while drinking [11]. Such correlations are not ubiquitous, however, with some studies finding no relationship between testosterone and alcohol use, especially when controlling for factors such as pubertal status [15, 13]. Even to the extent that such correlations are evident between testosterone levels and alcohol consumption and problems in humans, these correlations do not necessarily indicate causality, with other personality and social factors perhaps in part mediating this relationship in humans [32].

The relationship between testosterone levels and ethanol intake appears to be bidirectional, with testosterone not only influencing ethanol consumption, perhaps in a species specific manner, but alcohol use itself inhibiting testosterone secretion in the testes of rats and humans [1, 30, 27, 39]. Indeed, testosterone levels in male alcoholics have often been found to be lower than among healthy controls, but to rise during abstinence, with some studies reporting a return to normal levels within three weeks [16] or more [43] or even to over shoot control levels of the hormone [28]. In the current study, testosterone levels were obtained after a period of voluntary ethanol consumption, and hence the extent to which this consumption may have influenced plasma testosterone concentrations of SH and NM animals cannot be determined. Nevertheless, at the end of the consumption period, testosterone levels of the SH and NM animals were similar to those of RPL animals, suggesting that the replacement pellets were effective in restoring testosterone levels to control levels, at least under circumstances of voluntary consumption.

Overall, the results of the present study show that replacement of testosterone returned ethanol drinking and preference of adult castrates to levels similar to those of SH and NM males, supporting the suggestion that testosterone plays a role in moderating ethanol consumption, and likely contributes to sex differences in ethanol consumption commonly seen in adult rats [31]. Chronic ethanol exposure also reduces levels of this neuroactive steroid in the cortex [37], with allopregnanolone administration itself reported to alter operant responding for ethanol in males [19]. Whether such testosterone/allopregnanolone or ethanol/allopregnanolone interactions contribute to the effects of testosterone replacement on patterns of ethanol consumption provide interesting avenues for future study.

Research Highlights.

Gonadectomy in male rats previously resulted in increased ethanol intake in adulthood

Intake was measured after castration and replacement with testosterone or placebo

Hormone replacement returned drinking of castrates to levels similar to sham and non-manipulated controls

These data support a role for testosterone in moderating ethanol intake of adult male rats

Acknowledgements

Funding acknowledgements: This research was supported by NIAAA grant R01-AA017355. A special thank you to Judy Sharp for conducting the BEC and testosterone assays.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adams ML, Meyer ER, Cicero TJ. Interactions between alcohol- and opioid-induced suppression of rat testicular steroidogenesis in vivo. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:684–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida OF, Shoaib M, Deicke J, Fischer D, Darwish MH, Patchev VK. Gender differences in ethanol preference and ingestion in rats. The role of the gonadal steroid environment. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2677–2685. doi: 10.1172/JCI1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begg DP, Weisinger RS. The role of adrenal or testicular hormones in voluntary ethanol and NaCl intake of crowded and individually housed rats. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell RL, Rodd ZA, Lumeng L, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. The alcohol-preferring P rat and animal models of excessive alcohol drinking. Addict Biol. 2006;11:270–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2005.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernard DJ, Chapman SC, Woodruff TK. Mechanisms of inhibin signal transduction. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2001;56:417–450. doi: 10.1210/rp.56.1.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cailhol S, Mormede P. Sex and strain differences in ethanol drinking: effects of gonadectomy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:594–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan KK, Neighbors C, Gilson M, Larimer ME, Marlatt AG. Epidemiological trends in drinking age and gender: providing normative feedback to adults. Addict Behav. 2007;68:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chester JA, de Paula Barrenha G, DeMaria A, Finegan A. Different effects of stress on alcohol drinking behaviour in male and female mice selectively bred for high alcohol preference. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:44–53. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmer SG, Swanson MR. An evaluation of ten pairwise comparison procedures by monte carlo methods. J Am Stat Assoc. 1973;68:66–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doremus TL, Brunell SC, Rajendran P, Spear LP. Factors influencing elevated ethanol consumption in adolescent relative to adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1796–1808. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183007.65998.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dotson LE, Robertson LS, Tuchfeld B. Plasma alcohol, smoking hormone concentrations and self-reported aggression. J Stud Alc. 1975;36:578–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckardt MJ, File SE, Gessa GL, et al. Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on the central nervous system. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:998–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eriksson PCJ, Kaprio J, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ. Testosterone and alcohol use among adolescent male twins: Testing between-family associations in within-family comparisons. Behav Genet. 2005;35:359–368. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-3228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenfield SF. Women and alcohol use disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002;10:76–85. doi: 10.1080/10673220216212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handa K, Ishii H, Kono S, et al. Behavioral correlates of plasma sex hormones and their relationships with plasma lipids and lipoproteins in Japanese men. Atherosclerosis. 1997;130:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)06041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinz A, Rommelspacher H, Graf KJ, Kurten I, Otto M, Baumgartner A. Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, prolactin, and cortisol in alcoholics during withdrawal and after three weeks of abstinence: comparison with healthy control subjects. Psychiatry Res. 1995;56:81–95. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)02580-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilakivi-Clarke L, Goldberg R. Gonadal hormones and aggression-maintaining effect of alcohol in male transgenic transforming growth factor-alpha mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:708–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Laboratory Animal Research, National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janak PH, Gill TM. Comparison of the effects of allopregnanolone with direct GABAergic agonists on ethanol self-administration with and without concurrently available sucrose. Alcohol. 2003;30:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalra PS, Kalra SP. Circadian periodicities of serum androgens, progesterone, gonadotropins and luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in male rats: the effects of hypothalamic deafferentation, castration and adrenalectomy. Endocrinology. 1977;101:1821–1827. doi: 10.1210/endo-101-6-1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalra PS, Kalra SP. Regulation of gonadal steroid rhythms in rats. J Steroid Biochem. 1979;11:981–987. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(79)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.La Grange L, Jones TD, Erb L, Reyes E. Alcohol consumption: biochemical and personality correlates in a college student population. Addict Behav. 1995;20:93–103. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lancaster FE, Brown TD, Coker KL, Elliott JA, Wren SB. Sex differences in alcohol preference and drinking patterns emerge during the early postpubertal period. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1043–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leal AM, Moreira AC. Daily variation of plasma testosterone, androstenedione, and corticosterone in rats under food restriction. Horm Behav. 1997;31:97–100. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le AD, Israel Y, Juzytsch W, Quan B, Harding S. Genetic selection for high and low alcohol consumption in a limited-access paradigm. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1613–1620. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levitt MD, Furne J, DeMaster EG. Magnitude, origin, and implications of the discrepancy between blood ethanol concentrations of tail vein and arterial blood of the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 18:1237–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little PJ, Adams ML, Cicero TJ. Effects of alcohol on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in the developing male rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263:1056–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin WR, Hewett BB, Baker AJ, Haertzen CA. Aspects of the psychopathology and pathophysiology of addiction. Drug Alcohol Depen. 1977;2:185–202. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(77)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mock EJ, Norton HW, Frankel AI. Daily rhythmcity of serum testosterone concentration in the male laboratory rat. Endocrinology. 1978;103:1111–1121. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-4-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orpana AK, Orava MM, Vihko RK, Harkonen M, Eriksson CJ. Role of ethanol metabolism in the inhibition of testosterone biosynthesis in rats in vivo: importance of gonadotropin stimulation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;37:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(90)90338-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pluchino N, Ninni F, Casarosa E, Lenzi E, Begliuomin S, Cela V, et al. Sexually dimorphic effects of testosterone administration on brain allopregnanolone in gonadectomized rats. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2780–2792. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds MD, Tarter R, Kirisci L, et al. Testosterone levels and sexual maturation predict substance use disorders in adolescent boys: A prospective study. Biol Psychiat. 2007;61:1223–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silveri MM, Spear LP. Ontogeny of ethanol elimination and ethanol-induced hypothermia. Alcohol. 2000;20:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherrill LK, Koss WA, Foreman ES, Gulley JM. The effects of pre-pubertal gonadectomy and binge-like ethanol exposure during adolescence on ethanol drinking in adult male and female rats. Behav Brain Res. 2010;216:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strong MN, Yoneyama N, Fretwell AM, Snelling C, Tanchuck MA, Finn DA. "Binge" drinking experience in adolescent mice shows sex differences and elevated ethanol intake in adulthood. Horm Behav. 2009;58:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. 2007

- 37.Tanchuck MA, Long SL, Ford MM, Hashimoto J, Crabbe JC, Roselli CE, et al. Selected line difference in the effects of ethanol dependence and withdrawal on allopregnanolone levels and 5alpha-reductase enzyme activity and expression. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:2077–2087. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toebosch AMW, Robertson DM, Trapman J, et al. Effects of FSH and IGF-I on immature rat Sertoli cells; inhibin α- and β-subunit mRNA levels and inhibin secretion. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1988;55:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(88)90096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valimaki M, Tuominen JA, Huhtaniemi I, Ylikahri R. The pulsatile secretion of gonadotropins and growth hormone, and the biological activity of luteinizing hormone in men acutely intoxicated with ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1990;14:928–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb01840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Damme MP, Robertson DM, Marana R, Ritzen EM, Diczfalusy E. Aromatization of Androgens by Sertoli Cells: A Sensitive and Specific Bioassay for FSH Activity. In: Steinberger A, Steinberger E, editors. Testicular Development, Structure, and Function. New York: Raven Press; 1980. pp. 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vetter-O’Hagen CS, Spear LP. The effects of gonadectomy on age- and sex-typical patterns of ethanol consumption in Sprague-Dawley rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01555.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vetter-O'Hagen CS, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Sex differences in ethanol intake and sensitivity to aversive effects during adolescence and adulthood. Alcohol Alcsm. 2009;44:547–554. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walter M, Gerhard U, Gerlach M, Weijers H, Boening J, Wiesbeck GA. Controlled study on the combined effects of alcohol and tobacco smoking on testosterone in alcohol-dependent men. Alcohol Alcsm. 2007;45:19–23. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]