Abstract

Purpose

To test the long-term effects of a mass media intervention that used culturally and developmentally appropriate messages to enhance HIV-preventive beliefs and behavior of high-risk African-American adolescents.

Methods

Television and radio messages were delivered over three years in two cities (Syracuse, NY and Macon, GA) that were randomly selected within each of two regionally matched city pairs with the other cities (Providence, RI and Columbia, SC) serving as controls. African American adolescents ages 14 to 17 (N = 1710), recruited in the four cities over a 16-month period, completed audio computer-assisted self-interviews at recruitment and again at 3, 6, 12 and 18-months post-recruitment to assess the long-term effects of the media program. To identify the unique effects of the media intervention, youth who completed at least one follow-up and who did not test positive for any of three sexually transmitted infections at recruitment or at 6 and 12-month follow-up were retained for analysis (N=1346).

Results

The media intervention reached virtually all of the adolescents in the trial and produced a range of effects including improved normative condom-use negotiation expectancies and increased sex refusal self-efficacy. Most importantly, older adolescents (ages 16-17) exposed to the media program exhibited a less risky age trajectory of unprotected sex than those in the non-media cities.

Conclusions

Culturally tailored mass media messages delivered consistently over time have the potential to reach a large audience of high-risk adolescents, to support changes in HIV-preventive beliefs, and to reduce HIV-associated risk behaviors among older youth.

Keywords: mass media interventions, HIV-prevention, African American adolescents, condom use, culturally sensitive messages

HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) threaten the health and well being of poor African American communities. The incidence of HIV is seven times higher among African Americans than among whites1 with disproportionate transmission through heterosexual contact.2 Young people are particularly at risk. In 2007, African Americans ages 13 to 29, while only 17% of the population, represented 72% of new HIV/AIDS cases in this age range.3 African-American youth are also disproportionately affected by other STIs that increase the odds of HIV infection. 4, 5 Given these patterns, it is urgent to develop HIV/STD prevention interventions that can reach large proportions of African-American adolescents at risk for STIs and HIV.

Mass media interventions are well-suited to meet these goals because of their wide reach6 and ability to provide culturally tailored and developmentally appropriate risk reduction content.7, 8 Furthermore, because adolescents often feel uncomfortable discussing sexual matters with parents, mass media messages can be an effective tool for providing accurate information related to HIV/STDs.9 Experience with media interventions for adolescents in the U. S.10-12 and elsewhere13-15 suggests that media messages can promote safer sexual behavior in entire communities. Until recently no attempt had been made to evaluate HIV-prevention media campaigns directed specifically to high-risk African-American communities. In 2006, project iMPPACS1 launched a culturally and developmentally sensitive media program for African American youth in two midsized U.S. cities with high STI and HIV rates. Based on formative research,16, 17 the intervention used dramatic vignettes that showed adolescents resolving dilemmas regarding safer sex, especially condom use, as well as resisting pressures to engage in sex.

We previously reported effects of the media program for youth during the recruitment period of the intervention (an average of 8 months of media exposure). To identify high-risk youth, we screened all adolescents who participated in the trial for three STIs. We predicted that the media intervention would have its greatest effects among the highest-risk adolescents (i.e., the 6.5% who tested STI positive) who would recognize their vulnerability to infection and relate well to the characters and dilemmas depicted in the media messages. Nevertheless, we also expected the media program to affect all youth who engage in unprotected sex. Although the intervention improved a wide range of HIV-preventive beliefs, it only reduced unprotected sex among the highest risk youth.16

In this study, we present results extending beyond the recruitment period to include longer-term effects of the media program during an 18-month follow-up period. We expected that continued exposure to the media intervention would reduce age-related increases in sexual risk behavior beyond the effects originally observed among the small group of very high-risk adolescents.16 We also sought to determine whether the broader effects on HIV-preventive beliefs observed during the recruitment period would persist during the follow-up.

Methods

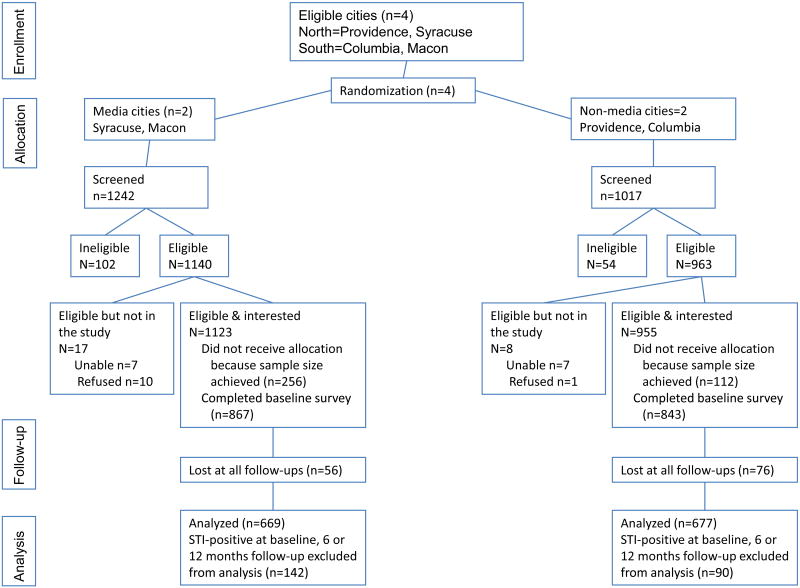

The study was approved by the participating universities' Institutional Review Boards. We previously described the recruitment procedure depicted in Figure 1.16, 18 Briefly, 1710 African American adolescents were recruited at a constant monthly rate from community-based organizations and street outreach as well as by peer nomination and respondent driven sampling in two northeast (Providence, RI and Syracuse, NY) and two southeast U.S. cities (Columbia, SC and Macon, GA) that were matched for high rates of STIs, HIV/AIDS, and adolescent pregnancy. Following informed assent by respondents and consent by parent(s)/guardian(s), participants completed audio, computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) lasting about 45 minutes and were then randomly assigned to either a small-group HIV-prevention or a general health intervention. They completed follow-up assessments at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after recruitment. Analysis showed that the only resulting differences between these group interventions involved knowledge of STIs and HIV. Since there were no differences between these interventions in any of the outcomes analyzed here, they are not discussed further. Youth received $30 for completing the initial assessment with gradual monetary increases for subsequent assessments.

Figure 1.

recruitment and retention, project iMPPACS

Syracuse and Macon were randomly assigned to receive the media campaign with Columbia and Providence serving as controls. Throughout the 16-month recruitment and 18-month follow-up periods, media messages were placed after school and on evenings and weekends on channels popular among African-American adolescents. Ads varied in content and appeal and were replaced at the midpoint of the intervention to keep the messages fresh and engaging (see http://www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/ShowPage.aspx?myID=62 for copies of the ads). Ads ran at a constant rate of a little less than three television and three radio spots on average per month per audience member with half that rate during the months of November and December. Detailed information about the content and development of the media messages is available in previous reports.16, 18

Adolescents were tested for three STIs at recruitment and at 6, 12, and 18 months post-recruitment. STI-positive youth received treatment and CDC compliant standard of care. We found that adolescents who tested positive at recruitment in control cities subsequently reduced sexual risk behaviors, while STI-negative youth did not exhibit changes in sexual behavior after screening.19 Additionally, the media program decreased unprotected sexual contacts among STI-positive youth prior to STI-screening and treatment at recruitment.16 Furthermore, there were no media effects on subsequent incidence of STIs. Given our interest in determining the effects of the media intervention apart from the effects of STI treatment and counseling, adolescents testing STI-positive at recruitment or at 6- or 12-month follow-up (n = 232) were not included in the current analysis. None of the patterns in our findings would be different if they were included, but an adequate discussion of the media intervention effects in combination with receipt of a positive STI screen exceeds the space limitations for this report and will be described in separately.

Predictors

Demographics and media exposure

Respondent age (14-15 vs. 16-17 at recruitment), gender (female=1; male=0), and media city (1 = yes; 0 = no) were included in all models. To test whether the media campaign had a cumulative impact over the follow-up period, we entered the simple effect of “wave” (recruitment, 3, 6, 12 and 18 months) and the interaction between this variable and media city. To assess media campaign awareness, participants were exposed to portions of the television and radio messages (as well as foils) at the 6-, 12 and 18-month assessments and were asked whether they had ever seen or heard them.

Risk groups

Although we expected the media intervention to have broader effects as it unfolded than were observed at recruitment, we nevertheless expected it to have the strongest effects among those with sexual experience at recruitment, since they would find the messages most relevant to their risk of infection throughout the period of media exposure. Three levels of risk were thus considered ranging from: (a) highest (sexually experienced at recruitment), (b) moderate (initiated sex during the trial), and (c) lowest (no lifetime sexual experience). We examined differences in media effects across these groups as well as differences in age with older youth (ages 16-17) expected to find the messages more relevant than younger youth (ages 14-15).

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, two sexual behavioral variables were examined: (a) number of vaginal sex partners and (b) a count of the number of episodes of unprotected vaginal, anal, or oral sexual contact (past 3 months). Only youth with sexual experience were included in the analysis on sexual behavior (n = 1160). To assess effects of the media intervention on social-cognitive beliefs supporting behavior change, five dependent variables were examined: (1) normative expectancies for condom-use negotiation, (2) personal expectancies for condom-use, (3) beliefs that condoms are not needed with “safe partners,” (4) intentions to use condoms, and (5) sex-refusal self-efficacy.

Table 1. Dependent variables with descriptive statistics at recruitment.

| Dependent variable | Variable description |

|---|---|

| Number of vaginal partners | The number of vaginal sex partners in the last three months. Respondents who had not had sex in the last three months were coded as 0. Responses ranged from 0-30 (21 extreme outliers were excluded from analysis). Mean = 1.40, SD = 2.35. |

| Unprotected sex contacts | The sum of three items that asked respondents how many times in the last three months they (or their sexual partner) had not used condoms when having vaginal, oral, or anal sex. Such counts of unprotected sex contacts are regarded as the best way to evaluate the risk of STI/HIV contraction.36 Unprotected vaginal sex contacts were correlated with anal (Spearman r = .231, P < .001) and oral (Spearman r = .282, P < .001) unprotected contacts. We summed responses to the three types of exposures to create an overall score of unprotected sex (ranging from 0 to 70). Extreme outliers were excluded from analysis (23 observations). Validity for this score has been reported elsewhere.16 Mean = 1.33, SD = 4.19. |

| Expectations for negative condom negotiation outcomes | The sum of responses to the following items from the condom negotiation outcome expectancy scale37: if you talked to a potential sex partner about using condoms, he/she would (a) not respect you more; (b) threaten to leave you; (c) not feel more affection for you; (d) swear at you; (e) hit, push or kick you; (f) threaten to break up with you; (g) not feel safer (1= very unlikely to 6= very likely). Mean = 2.11, SD = .84, polychoric alpha (α) = .82. |

| Expectations that condoms hinder pleasure | Sum of responses to the following items from the Condom Attitude Scale:38 (a) Condoms take away the pleasure a guy has during sex; (b) condoms are messy; (c) condoms make sex hurt for girls; (d) condoms take away the pleasure of sex; and (e) using condoms takes “the wonder” out of sex (1=strongly disagree to 6=strongly agree,). Mean = 2.62, SD = 1.13, polychoric α= .83 |

| Intentions to use condoms | Sum of responses to the following items: if I have vaginal sex in the next 3 months (a) I intend to use a condom every time and (b) I am willing to use a condom every time (1=strongly agree, 6=strongly disagree). Mean = 5.25, SD = 1.27. |

| Expectations that condoms are not needed with “safe” partners | The sum of three items from the Condom Attitude Scale:38 Condoms are not needed (a) if you are sure the other person does not have an STD, (b) if you know your partner and (c) if you and your partner agree not to have sex with anyone else (1=strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree;). Mean = 2.03, SD = 1.25, polychoric α = .85. |

| Lack of self-efficacy to refuse sex | Based on the mean of items (a) to (d) from the Sex Refusal Self-Efficacy Scale39 and items (e) and (f) from the perceived difficulties of performing AIDS preventive behavior scale:40 Responses were converted to z scores before averaging (α = .71). How sure are you that you would be able to say no to having vaginal sex: (a) if you have known the person for a few days or less, (b) if you want to date him or her again, (c) if you want the person to fall in love with you, (d) if the person is pressuring you to have sex (1=I definitely could say, 4=I definitely could not say no); and How hard or easy would it be for you to (e) wait to have sex until you are several years older or wait to have sex again if you already had sex, and (f) tell your boyfriend or girlfriend you are not going to have sex with them (1=very easy, 6=very hard). Mean = 0, SD = .76, polychoric α = .89. |

To validate that intervention differences were attributable to the media program and not to pre-existing differences in adolescent risk taking, we compared cities on several health risks unrelated to the media campaign: (a) substance use expectations (smoking/drinking would be very bad vs. very good for me; smoking would be very risky for my health vs. not at all risky) and (b) peer norms for smoking (how many friends smoke cigarettes: almost all to none). We also examined city differences in: (c) reported alcohol use (never drank vs. drank 100 or more days in lifetime), and (d) cigarette and (f) cannabis use (never vs. at least once). Lastly, because the media intervention did not attempt to affect condom availability, we examined city differences on a composite score that assessed differences in perceived difficulty of carrying condoms (very hard vs. very easy).

We also increased the equivalence between intervention and control cities by adjustment of potentially uncontrolled background factors using a propensity score approach20, 21 to construct inverse probability weights for individual observations (see Romer et al.,16 for further details). The pweight Stata command was used to implement this procedure in all analyses.

Data Analysis

To examine changes in social-cognitive outcomes over time, we used linear Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE). For partner and condom use outcomes, we used negative binomial GEE regressions. A total of 132 youth did not complete any follow-up assessments and an additional 252 participants completed at least one but not all follow-up assessments. Analyses indicated that males and adolescents from Providence were more likely to drop out of the study. GEE is robust for managing missing data.22, 23 Thus, we report on models that included participants that had at least one follow-up record (N=1346). Models were estimated using an unstructured working correlation matrix.

All models were conducted sequentially, starting with all simple effects (gender, age, sexual experience category, assessment point, and media city). We then included higher-order interactions to assess whether media effects differed by age and sexual experience. Only significant (p < .05) higher order interactions were included in the final models. While our analysis involved multiple tests across relevant outcomes, we only considered unprotected sex as an intervention endpoint. Hence, we did not use a correction for multiple tests in reporting the findings. Analyses were conducted using Stata 10,23 and the lincom command was used to examine differences in slopes and intercepts for media and non-media cities within the different risk groups.

Results

Media exposure

As reported previously, the media program achieved high exposure during the recruitment period.16 On average, from 48% to 87% of the adolescents in media cities reported having seen one of the intervention TV ads, while only 10% to 14% of youth in nonmedia cities reported (mistakenly) seeing those ads, a level of false recognition that is common for advertising.24 Recognition of radio ads was also greater in the media cities but at lower levels (22% to 50% vs. 7%). Thus, the intervention reached the intended target audience despite the presence of other messages that potentially originated from national sources, such as MTV (there were no local media STD/HIV prevention campaigns in any city).

Demographics

Participants' ages ranged from 14 to 17 (M = 15, SD = 1.05) with 763 (57%) female respondents. There were slightly fewer males in Macon and adolescents in Syracuse were slightly younger. A total of 186 participants (14%) reported no lifetime sexual experience throughout the trial, 407 (30%) respondents initiated sex during the trial, and 753 (56%) respondents were sexually experienced at recruitment. Compared to uninitiated, those who were sexually active at recruitment were more likely to be male and older, and the adolescents who initiated sex during the trial were more likely to be older (Table 2). There were no city differences related to sexual experience.

Table 2. Risk groups by age and gender.

| Risk groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninitiated n=186 (14%) n (%) |

Initiated during Trial n=407 (30%) n (%) |

Experienced at Recruitment n=753 (56%) n (%) |

Total n=1346 n (%) |

|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 146 (78) | 268 (66) | 349 (46) | 763 (57) |

| Male | 40 (22) | 139 (34) | 404 (54)* | 583 (43) |

| Age | ||||

| 14-15 | 155 (83) | 318 (78) | 427 (56) | 900 (67) |

| 16-17 | 31 (17) | 89 (22)* | 326 (43)* | 446 (33) |

Note: Significant differences (*p<.05) are based on logistic regression models using dummy variables for each sexual risk category and uninitiated youth as the reference category.

Media Effects

Table 3 shows the results of models testing the impact of the media intervention on HIV-preventive beliefs among all participants and sexual behavior outcomes for youth who were sexually experienced at some point during the trial. Model 1 shows that the lack of self-efficacy to refuse sex was stronger in the non-media than media cities among experienced youth (Figure 2a). Indeed, the intercept was significantly lower in the sexually experienced group (p=.009), indicating that this effect was maintained from time of recruitment.

Table 3. Final weighted GEE models of sex refusal self-efficacy and outcome expectancies among all adolescents (models 1-5, N=1346) and of vaginal sex partners and unprotected sex contacts among sexually experienced adolescents (models 6-7, N=1160).

| Covariates | Model 1 Low sex refusal self-efficacy | Model 2 Condoms not needed with safe partner | Model 3 Low intentions to use condoms | Model 4 Negative condom negotiation expectancy | Model 5 Condoms hinder pleasure | Model 6 Vaginal sex partners | Model 7 Unprotected sex contacts | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Prob | B | Prob | B | Prob | B | Prob | B | Prob | IRR | Prob | IRR | Prob | |

| Female (1) vs. Male (0) | -0.66 | <0.001 | -2.22 | <0.001 | -0.57 | 0.014 | -1.60 | 0.001 | -2.68 | <0.001 | 0.72 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.110 |

| Older (1) vs. Younger (0) | -0.05 | 0.234 | 0.70 | 0.015 | 0.71 | 0.012 | 1.05 | 0.040 | 1.94 | 0.042 | 1.00 | 0.958 | 1.23 | <0.001 |

| Initiated during trial | 0.07 | 0.282 | 0.64 | 0.216 | 0.39 | 0.166 | -1.60 | 0.016 | -0.01 | 0.989 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Experienced at recruitment | 0.32 | <0.001 | 2.08 | 0.002 | 1.08 | <0.001 | -1.45 | 0.022 | 0.77 | 0.095 | 2.02 | <0.001 | 1.61 | <0.001 |

| Media (1) vs. NonMedia city (0) | 0.04 | 0.551 | 1.16 | 0.279 | 0.18 | 0.472 | -0.88 | 0.030 | -0.28 | 0.486 | 1.08 | 0.251 | 1.05 | 0.318 |

| Wave (1-5) | -0.06 | 0.203 | 0.19 | 0.119 | 0.32 | 0.061 | -0.01 | 0.953 | <0.01 | 0.998 | 1.04 | 0.005 | 1.05 | <0.001 |

| Older * media | -2.51 | 0.022 | 0.88 | 0.037 | ||||||||||

| Media * wave | -0.43 | 0.034 | ||||||||||||

| Experienced * media | -0.15 | 0.047 | -2.52 | 0.049 | -0.92 | 0.017 | ||||||||

| Experienced * wave | -0.42 | 0.030 | ||||||||||||

| Experienced * wave * media | 0.57 | 0.035 | ||||||||||||

Note: Coefficients in models 1 – 5 are unstandardized regression coefficients. For example, females report less low-sex-refusal efficacy than males on the scale defined in Table 1. In models 6-7, the coefficients are incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with values greater than 1 indicating higher incidence and values less than 1 indicating lower incidence. Thus, females report a 28% lower incidence of sexual partners than males.

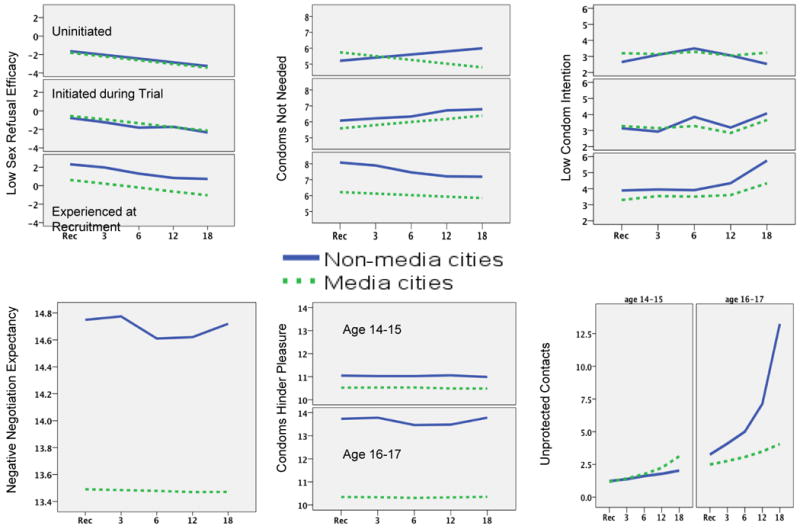

Figure 2a-f.

Weighted predicted means for following outcomes by risk group (where applicable), media versus non-media cities, and time of assessment in months from recruitment (Rec) for (a) low sex refusal self-efficacy, (b) condoms not needed with safe partners, (c) low intentions to use condoms, (d) negative condom negotiation expectancy, (e) condoms hinder sexual pleasure, and (f) unprotected sexual contacts.

Model 2 shows a media effect (media × wave) for the expectation that condoms are not needed with “safe” partners. However, as seen in Figure 2b, the effect was particularly strong for adolescents who were sexually experienced at recruitment with a significant intercept difference at the time of recruitment (p=. 049). In addition, as also seen in Figure 2b, there was a significant three-way interaction (experienced × wave × media city), indicating that youth who remained uninitiated during the trial in non-media cities displayed increasingly risky beliefs over time, whereas the experienced in media cities showed the opposite tendency (p=.035).

Model 3 shows that the intervention maintained intentions to use condoms in sexually experienced youth (Figure 2c); this was confirmed in a test of intercept differences that was only significant in this risk group (p=.008).

Model 4 shows that the intervention reduced negative condom negotiation expectancies, an effect that was evident across all risk groups (Figure 2d).

Model 5 shows that the intervention lowered the belief that condoms hinder pleasure among the older cohort. Indeed, there was a significant intercept difference from the point of recruitment (p=.005). Although Figure 2e shows a tendency towards lowered risk among the younger adolescents in media cities, this difference was not significant (p=.486).

Models 6-7 show results for sexual risk behavior. While number of recent partners increased over waves (model 6), there was no effect of the intervention on this outcome. However, as expected, the intervention did reduce unprotected sexual contacts. Older adolescents in media cities were less likely to engage in unprotected sex over the study period than their counterparts in non-media cities. As seen in Figure 2f, the trajectory for reports of unprotected sex contacts rose sharply in the non-media cities, while it remained much lower in the media cities. At the last wave, youth in the nonmedia cities reported over 4 times more unprotected sex contacts than those in the media cities. There were no differences for youth under the age of 16 at recruitment; however, as seen in Figure 2f, their trajectory of unprotected sex was not yet on the rise in either city.

To confirm that the observed city differences were not attributable to trends that would have occurred in the absence of the media campaign (e.g., riskier behavior in non-media cities), we compared cities on other risk behaviors. These analyses showed that adolescents in the media cities were if anything riskier, not safer, than adolescents in the non-media cities. Uninitiated youth in the media cities had more positive substance use expectancies than their counterparts in non-media cities (B=.327, p=.024). Both uninitiated and sexually experienced youth reported more cigarette use in media than in non-media cities (uninitiated OR=3.195, p<.001, sexually experienced OR=1.488, p=.017). Finally, there were no city differences in perceived difficulties of carrying condoms, an outcome that was not targeted in the media intervention (p=.620).

Discussion

This study presents results from the first large scale test of a mass media program designed to reduce sexual risk-taking behavior among at-risk African American adolescents. Although mass media campaigns have been found to augment HIV/STI prevention efforts, 6 little research has been conducted in the U. S. on the efficacy of mass media messages alone to alter sexual behavior in high-risk youth. We previously reported very limited results from the 16-month recruitment phase of this intervention showing that the media program reduced unprotected sex among the most at risk youth (those carrying undetected STIs). The present study shows that similar effects were observable over the longer 18-month follow-up period for the larger group of youth ages 16 and 17 at recruitment who did not receive treatment for STIs during the trial. While risk behavior increased dramatically during this period for older youth in the non-media cities, the trajectory in the media cities was reduced considerably.

We also found that the media program enhanced several social-cognitive outcomes that were intended to support behavior change. Indeed, many of these effects were observed during the recruitment period and were sustained over time. In particular, more favorable condom use negotiation expectations persisted among all adolescents, indicating that the media program produced favorable normative expectations regarding partner acceptance of condom use. Furthermore, the media intervention dispelled beliefs that condoms hinder pleasure among older youth and improved intentions to use them among the most sexually experienced. In addition, messages designed to convince adolescents of the benefits of delaying sexual intercourse or using a condom even with partners who might otherwise seem “safe” were particularly effective among the most sexually experienced youth, and the latter outcome grew in acceptance among those who remained uninitiated. These differential effects, which tended to be stronger among the older or more experienced youth, were likely the result of differing levels of relevance of the messages to the audience.25-27 Indeed, older adolescents were more likely to be sexually experienced at recruitment and thus to have greater personal experience of negotiating safer sex practices with partners. Such youth may have been particularity likely to relate to the dramatic depictions in the media messages, thereby creating an opportunity for applying the situations to their own experience. Nevertheless, it is important to note that in terms of influences on condom use, we observed media effects in older youth regardless of whether they were experienced at recruitment or only during the trial.

The finding that media effects expanded to a larger segment of the target audience over the study period is consistent with Bandura's theory28 of mass media that asserts that media messages have a “prompting” function that can elicit previously learned skills and behavior. This function became visible as adolescents aged into opportunities for riskier sexual behavior. Although the older cohort in the non-media cities exhibited an increase in unprotected sex, this tendency was muted among youth exposed to the media intervention. If this interpretation is correct, we might expect to see effects of the intervention even among younger youth as they also age into higher risk behavior trajectories. To test this hypothesis, a 3-year follow-up assessment (1 year after the end of the media campaign) is currently being conducted.

Although our media messages reduced unprotected sex, they did not lead to a reduction in number of partners. This may reflect the fact that the majority of the media messages focused on condom use and the ability to refuse or delay sex with new partners rather than avoiding concurrent or serial partners. It may also be that partner reduction is difficult to achieve with an adolescent audience. Nevertheless, because rate of partner acquisition is an important driver of STI transmission, it is also important for future HIV prevention programs to intervene with youth who engage in frequent partner turnover or concurrency.

Limitations

One limitation of the study design is the reliance on self-report, which can be influenced by memory or motivational biases; however, the use of ACASI should have reduced this potential bias.29 Second, we did not assess adolescents prior to the introduction of the media intervention, and we observed only four cities, making it difficult to control random effects. However, we compensated by using propensity score weighting30 and by examining risk behavior and expectancies not directly linked to the media campaign (a type of discriminant evidence of efficacy). Because the differences we found on these discriminant variables indicated that the media cities were more risky than the non-media cities, we can be more confident that the differences in sexual attitudes and condom use behavior can be attributed to the media intervention and not to pre-existing or evolving differences between cities. Additionally, the cities were selected because they did not have local risk reduction campaigns and pilot work indicated that youth were similarly sexually experienced in the four cities (also corroborated in the trial). Thus, it is unlikely that the differences we found predated the media intervention.

Conclusions

With African American youth disproportionately affected by STDs and HIV, mass media interventions offer a potentially powerful prevention approach because of their ability to reach this audience at a low cost.31 Media may also reach adolescents who cannot be influenced through face-to-face interventions or in clinical settings. In addition, mass media programs have the potential to be far more engaging than commonly believed.32 The program studied in this intervention used dramatic depictions of youth discussing and resolving dilemmas surrounding sexual behavior in situations relevant to high-risk audience members. These depictions were intended to enable the audience to identify with the portrayed characters and to use their behavior as a guide for their own decisions and behaviors. By reaching a wide audience repeatedly over time, the media can also produce expectations that other audience members will respond similarly, as reflected for example in our measure of expectations for condom negotiation. As such the relation between the media characters and audience can be far more active than otherwise assumed and can result in a relationship with a performer that is analogous to the interpersonal relationship of people in face-to-face interaction.33-35 This study therefore provides evidence that a culturally and developmentally appropriate media program can reach and influence youth within communities most in need of prevention intervention.

Acknowledgments

The data stem from a cooperative agreement funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health, Office on AIDS, Pim Brouwers, Project Officer. The following sites and investigators contributed to the project: Columbia, SC (MH66802), Robert Valois (PI), Naomi Farber, and Andure Walker; Macon, GA (MH66807), Ralph DiClemente (PI), Laura Salazar, Rachel Joseph, and Angela Caliendo; Philadelphia, PA (MH66809), Daniel Romer (PI), Sharon Sznitman, Bonita Stanton, Michael Hennessy, Ivan Juzang, and Thierry Fortune; Providence, RI (MH66875), Larry Brown (PI), Christie Rizzo, and Rebecca Swenson; Syracuse, NY (MH66794), Peter Vanable (PI), Michael Carey, Rebecca Bostwick, and Jennifer Brown.

Footnotes

iMPPACS is the acronym developed for the project as a multi-city program “in Macon, Providence, Philadelphia (in collaboration with Wayne State University, Detroit), Atlanta, Columbia, and Syracuse.”

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. HIV/AIDS surveillance report 2005, vol 17. Vol. 46. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2007. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. HIV/AIDS surveillance in adolescents and young adults (through 2007) [November 30, 2010]; http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/adolescents/index.htm.

- 4.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. Racial/Ethnic disparities in diagnoses of HIV/AIDS in 33 states, 2001-2004. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5505a1.htm?s_cid=mm5505a1_e. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. 2007 state and local youth risk behavior survey. http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/questionnaire/2007HighSchool.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noar SM. A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: Where do we go from here? J Health Commun. 2006;11(1):21. doi: 10.1080/10810730500461059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grier SA, Briumbaugh AM. Noticing cultural differences: Ad meanings created by target and non-target markets. J Advert. 1999;28:79. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grier SA, Deshpande R. Social dimensions of consumer distinctiveness: The influence of social status on group identity and advertising persuasion. J Mark Res. 2001;38(2):216. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creatsas G. Improving adolescent sexual behavior: A tool for better fertility outcome and safe motherhood. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;58(1):85. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(97)02871-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy MG, Mizuno Y, Seals BF, Myllyluoma J, Weeks-Norton K. Increasing condom use among adolescents with coalition-based social marketing. AIDS. 2000;14:1809. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200008180-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polen MR. Outcome evaluation of project action. Portland, OR: Oregon Health Division; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerman RS, Palmgreen PM, Noar SM, Lustria ML, Lu HY, Lee Horosewski M. Effects of a televised two-city safer sex mass media campaign targeting high-sensation-seeking and impulsive-decision-making young adults. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(5):810. doi: 10.1177/1090198107299700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.deVroome EM, Paalman ME, Sandfort TGM, Sleutjes M, deVries KJM, Tielman RAP. AIDS in the netherlands: The effects of several years of campaigning. Int J STD & AIDS. 1990;1:268. doi: 10.1177/095646249000100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hausser D, Michaud PA. Does a condom-promoting strategy (the swiss STOP-AIDS campaign) modify sexual behavior among adolescents? Pediat. 1994;93:580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hausser D, Zimmermann E, Dubois-Arber F, Paccaud FE. Evaluation of the swiss AIDS prevention policy (third assessment report) 1989-1990. Lausanne: Institute Universitaire de Medecine Sociale et Preventive; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romer D, Sznitman SR, Hennessy M, et al. Mass media as an HIV-prevention strategy: Using culturally sensitive messages to reduce HIV-associated sexual behavior of high risk African-American youth. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2150. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horner JR, Romer D, Vanable PA, et al. Using culture-centered qualitative formative research to design broadcast messages for HIV-prevention for african american adolescents. J Health Comm. 2008;13(4):309. doi: 10.1080/10810730802063215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanable PA, Carey MP, Brown JL, et al. Test-retest reliability of self-reported HIV/STD-related measures among african-american adolescents in four U.S. cities. J Adol Health. 2009;44(3):214. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sznitman SR, Carey MP, Vanable PA, et al. The impact of community-based STI screening results on sexual risk behaviors of african-american adolescents. J Adol Health. 47:12. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robins JM, Hernan M, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epid. 2000;11:550. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin DR. Estimating casual effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J Educ Psych. 1974;66:688. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghisletta P, Spini D. An introduction to generalized estimating equations and an application to assess selectivity effects in a longitudinal study on very old individuals. J Educ Behav Stat. 2004;29(4):421. [Google Scholar]

- 23.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh SN, Cole CA. Forced-choice recognition tests: A critical review. J of Advert Res. 1985;14(3):52–58. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papa MJ, Singhal A, Law S, et al. Entertainment-education and social change: An analysis of parasocial interaction, social learning, collective efficacy and paradoxical communication. J Commun. 2000;50(4):31. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singhal A, Rogers EM. Entertainment-Education: A Communication Strategy for Social Change. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sood S. Audience involvement and entertainment-education. Commun Theory. 2002;12(2):153. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A, Bryan J, Zillman D. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum; 1994. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romer D, Hornik R, Stanton B, et al. “Talking” computers: A reliable and private method to conduct interviews on sensitive topics with children. J Sex Res. 1997;34:3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lippman S, Shade SB, Hubbard AE. Inverse probability weighting in sexually transmitted infection/human immunodeficiency virus prevention research: Methods for evaluating social and community interventions. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2010;37(8):512–518. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d73feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen DA, Wu S, Farley TA. Cost-effective allocation of government funds to prevent HIV infection. Health Affairs. 2005;24(4):975. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noar MS, Pope C, White RT, Malow R. HIV/AIDS Global Frontiers in prevention/interventions. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. The utility of “old” and “new” media tools for HIV prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horton D, Wohl RR. Mass communication and para-social interaction. Psychiatry. 1956;19:215. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green MC, Brock TC, Kaufman GF. Understanding media enjoyment: The role of transportation into narrative worlds. Commun Theory. 2004;14(4):311–327. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deighton J, Romer D, McQueen J. Using drama to persuade. J Consum Res. 1989;16:335. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. accuracy of self-reports. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(2):104. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The effects of an abusive primary partner on the condom use and sexual negotiation practices of african-american women. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):1016. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.St Lawrence JS, Reitman D, Jefferson KW, Alleyne E, Brasfield TL, Shirley A. Factor structure and validation of an adolescent version of the condom attitude scale: An instrument for measuring adolescents' attitudes toward condoms. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:352. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cecil H, Pinkerton SD. Reliability and validity of a self-efficacy instrument for protective sexual behaviors. J Am Coll Health. 1998;47:113. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams SS, Doyle TM, Pittman LD, Weiss LH, Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Role-played safer sex skills of heterosexual college students influenced by both personal and partner factors. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2:177. [Google Scholar]