Abstract

This is a case report on a 35-year-old man with acute myelogenous leukemia who presented fever and intermittent mucoid loose stool to the emergency center. He had been taking voriconazole for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. The flexible sigmoidoscopy was consistent with the diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis.

Keywords: Pseudomembranous colitis, voriconazole, diarrhea, Clostridium difficile

INTRODUCTION

Diarrhea is a common complication of antimicrobial therapy and pseudomembranous colitis is the most severe form of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, marked by endoscopic features of a white to yellow layer lining the mucosa that is typically most prominent in the rectum, sigmoid colon and left colon.1 Pseudomembranous colitis has emerged as a significant medical problem over the past few decades, because of prevalent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Almost all antimicrobial agents with antibacterial activity have been implicated; however, pseudomembranous colitis after treatment with antifungal agents has rarely been reported.2 Here, the first case of pseudomembranous colitis which is likely associated with the antifungal agent voriconazole is reported.

CASE REPORT

A 35-year-old man presented to the emergency center with fever up to 39℃ for three days, and intermittent mucoid loose stool. The patient had previously been diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukemia five months ago. Two months ago, he underwent reinduction chemotherapy with mitoxantrone, cytarabine, and etoposide combination, however, failed to achieve complete remission. Fever developed during an episode of prolonged neutropenia, and imipenem/cilastatin (500 mg qid IV) was given empirically. After 7 days, the patient was diagnosed with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and treated first with amphotericin B deoxychoate (9 days), then changed to caspofungin (13 days), and finally switched to voriconazole (2 days). From the beginning of treatment with the antifungal agents, however, the patient's medication did not include antibacterials or antivirals. The patient received escitalopram for three months because of a major depression. Two days after starting voriconazole, the patient was discharged without any symptoms. When he came to the emergency center (3 days after discharge), the medication included only voriconazole (200 mg bid po) and escitalopram (10 mg qd po).

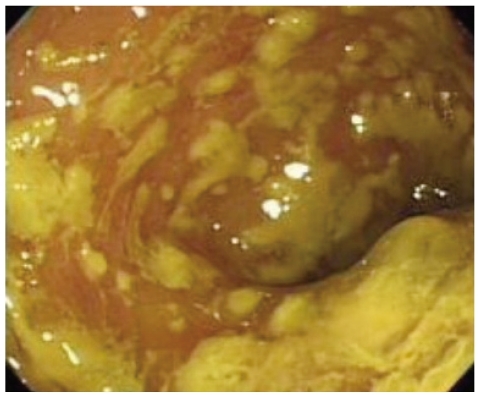

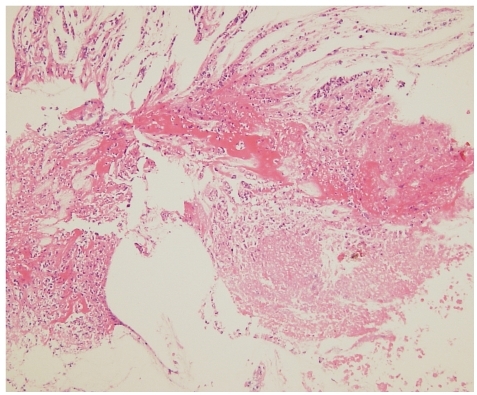

On examination, the patient had mild left lower quadrant pain without guarding or rebound tenderness. The stool examination for parasites and stool cultures for Salmonella and Shigella were all negative. Toxin assay for Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) was also negative. Flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed edematous mucosal changes and exudates with yellowish plaques which were consistent with pseudomembranous colitis (Fig. 1). Biopsies of the plaques were diagnostic of pseudomembranous colitis (Fig. 2). Metronidazole was started orally and voriconazole was discontinued; the symptoms improved and the patient continued the metronidazole to complete a 14-day course. After complete resolution of the symptoms, the patient underwent a second reinduction chemotherapy with amphotericin B deoxycholate and itraconazole for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. No relapse of the pseudomembranous colitis occurred. The pseudomembranous colitis in this case was likely associated with the voriconazole, according to the Naranjo probability scale (6 points) and by the World Health Organization-Uppsala Monitoring Centre causality categories.3,4

Fig. 1.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed mucosal edema and yellowish exudative plaques.

Fig. 2.

Biopsy showed volcano-like eruptions with superficial pseudomembrane formation adjacent to an area of mucosal necrosis and superficial erosions.

The pseudomembranous colitis was likely caused by voriconazole because of: 1) the sudden onset of diarrhea after 5-days of treatment with voriconazole, 2) no other possible medications associated with pseudomembranous colitis at the time of diarrhea and 3) the improvement of symptoms after discontinuation of the voriconazole.

DISCUSSION

Diarrhea is one of the most common side effects of antimicrobial treatment, occurring in 5-25% of all patients.5 The onset of C. difficile diarrhea usually occurs from 4-9 days after the beginning of antibiotic therapy and pseudomembranous colitis is the characteristic manifestation of full-blown C. difficile colitis.6 Stool tests for the diagnosis of C. difficile infection include cytotoxin assay, enzyme immunoassay, latex agglutination assay, and culture. Although the toxin assay for C. difficile was negative and the stool culture for C. difficile was not performed in this case, a negative enzyme immunoassay for toxins A and B does not rule out C. difficile associated diarrhea; however, the presence of pseudomembranes on sigmoidoscopy is considered diagnostic.1,7,8

Voriconazole is a generally well tolerated antifungal agent approved for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis. Visual disturbances, skin rashes and elevated liver enzyme levels are commonly noted adverse events.9 Pseudomembranous colitis associated with voriconazole has not previously been reported; however, the available information on the drug indicates it as one of the less common adverse events.10 To assess the objectivity, reliability and validity of causality in the assessment of an adverse drug reaction, the Naranjo probability scale and World Health Organization-Uppsala Monitoring Centre causality categories were used in this case.3,4 This patient developed pseudomembranous colitis 5-days after the treatment with voriconazole, was taking no other medications associated with pseudomembranous colitis at diagnosis, and improved after discontinuation of the voriconazole and initiation of oral metronidazole. The adverse event was confirmed by sigmoidoscopy; rechallenge was not performed. Overall, voriconazole showed a probable relationship with pseudomembranous colitis, according to both the Naranjo probability scale (6 points) and the World Health Organization-Uppsala Monitoring Centre causality categories.

There has been only one report on pseudomembranous colitis associated with the antifungal agent itraconazole.2 As this case indicated, antifungal agents may alter the microbial flora of the colon without direct activity against bacteria.2 Fungi, particularly Candida albicans, are considered microflora of the normal adult gastrointestinal tract,11 therefore, it is likely that the voriconazole altered the normal intestinal microflora followed by C. difficile exposure and colonization, resulting in mucosal injury of the colon and inflammation due to toxins, and finally the development of pseudomembranous colitis. Heard, et al.12 reported that acute leukemia or its treatment constitutes a significant risk factor for acquisition of C. difficile. This patient developed pseudomembranous colitis after remission induction chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia and this might have been an important additional factor associated with C. difficile colonization.

In summary, the present case suggests that pseudomembranous colitis may result from alteration of the fungal flora as well as bacterial microflora of the intestine, and that antifungal agents should be considered as a rare but possible cause of pseudomembranous colitis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant (09182KFDA3103) from Korea Food & Drug Administration in 2011.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Coté GA, Buchman AL. Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5:361–372. doi: 10.1517/14740338.5.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen AJ, Nelson DB, Thurn JR. Pseudomembranous colitis after itraconazole therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1971–1973. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2000;356:1255–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02799-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergogne-Bérézin E. Treatment and prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhea. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;16:521–526. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:375–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller M, Gravel D, Mulvey M, Taylor G, Boyd D, Simor A, et al. Health care-associated Clostridium difficile infection in Canada: patient age and infecting strain type are highly predictive of severe outcome and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:194–201. doi: 10.1086/649213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Högenauer C, Hammer HF, Krejs GJ, Reisinger EC. Mechanisms and management of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:702–710. doi: 10.1086/514958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson LB, Kauffman CA. Voriconazole: a new triazole antifungal agent. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:630–637. doi: 10.1086/367933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drug information. Available from: URL: http://www.pfizer.com/files/products/uspi_vfend.pdf.

- 11.Cohen R, Roth FJ, Delgado E, Ahearn DG, Kalser MH. Fungal flora of the normal human small and large intestine. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:638–641. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196903202801204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heard SR, Wren B, Barnett MJ, Thomas JM, Tabaqchali S. Clostridium difficile infection in patients with haematological malignant disease. Risk factors, faecal toxins and pathogenic strains. Epidemiol Infect. 1988;100:63–72. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800065560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]