Abstract

BACKGROUND

Human glioblastoma is a deadly brain cancer that continues to defy all current therapeutic strategies. We induced apoptosis in human glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells following treatment with apigenin (APG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), and genistein (GST) that did not induce apoptosis in human normal astrocytes (HNA).

METHODS

Induction of apoptosis was examined using Wright staining and ApopTag assay. Production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and increase in intracellular free [Ca2+] were measured by fluoresent probes. Analysis of mRNA and Western blotting indicated increases in expression and activities of the stress kinases and cysteine proteases for apoptosis. JC-1 showed changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and use of specific inhibitors confirmed activation of kinases and proteases in apoptosis.

RESULTS

Treatment of glioblastoma cells with APG, EGC, EGCG, or GST triggered ROS production that induced apoptosis with phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and activation of the redox-sensitive JNK1 pathway. Pretreatment of cells with ascorbic acid attenuated ROS production and p38 MAPK phosphorylation. Increases in intracellular free [Ca2+] and activation of caspase-4 indicated involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in apoptosis. Other events in apoptosis included overexpression of Bax, loss of ΔΨm, mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and Smac into the cytosol, down regulation of baculoviral inhibitor-of-apoptosis repeat containing proteins, and activation of calpain, caspase-9, and caspase-3. EGC and EGCG also induced caspase-8 activity. APG, EGC, EGCG, or GST did not induce apoptosis in HNA.

CONCLUSION

Results strongly suggest that flavonoids are potential therapeutic agents for induction of apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells.

Keywords: apoptosis, flavonoids, glioblastoma, T98G, U87MG

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma is the most common primary malignant brain tumor, comprising about 20% of all primary brain tumors in adults and it is also called grade IV astrocytoma.1 Glioblastoma is aggressive and characterized by rapid cell growth and local spread. Chemotherapy alone is not typically used for its treatment, but is often used as part of a multi-modality treatment strategy. The major limitations of chemotherapy for treatment of glioblastoma are the inability of many drugs to pass through the blood-brain barrier and their low efficacy for induction of apoptosis. Therefore, the choice of active drugs is limited. Many clinical trials are evaluating new therapeutic agents for treatment of newly diagnosed glioblastoma or recurrent disease.

Flavonoids constitute the largest and most important group of polyphenolic compounds in plants. Flavonoids are present in vegetables, fruit, and beverages of plant origin, which have anti-oxidant, anti-mutagenic, and anti-proliferative properties. 2–5 They may thus have a potential protective role in various chronic diseases, including cancers, 6–8 and explain, at least in part, the well-established associations between high consumption of vegetables and fruit and reduced risk of several neoplasms. Over the past few years, flavonoids have been demonstrated to act on multiple key elements in signal transduction pathways related to cellular proliferation, differentiation, cell-cycle progression, apoptosis, inflammation, angiogenesis, and metastasis; however, these molecular mechanisms of action are not completely characterized and many features remain to be elucidated. 9 It has been shown that flavonoids can trigger apoptosis through modulation of a number of key elements in cellular signal transduction pathways linked to apoptosis. Earlier studies suggest that flavonoids may exert regulatory activities in cells through actions at different signal transduction pathways such as cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), caspases, Bcl-2 family members, epidermal growth factor (EGF)/epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt, MAPK, and NF-κB, which may affect cellular function by modulating genes or phosphorylating proteins.10 It has been shown repeatedly that antioxidants and their derivatives selectively induce apoptosis in cancer cells but not in normal cells in culture. Apigenin (APG), a flavone abundantly found in fruits and vegetables, exhibits anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-metastatic activities. Treatment with APG was accompanied by an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and phosphorylation of the MAPKs, p38 and ERK. 11 (−)-Epigallocathecin (EGC) and (−)epigallocathecin-3-gallate (EGCG) are present in green tea at low level and reduce the proliferation of human breast cancer cells in vitro and decrease breast tumor growth in rodents.12 EGCG can induce apoptotic changes including loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1), caspase-9, and caspase-3.13 However, comprehensive mechanisms to explain the diverse effects of EGCG in causing apoptosis remain to be explored. Like most flavonoids, most genistein (GST) exists in nature in its 7-glycoside form, genistin, rather than in its aglycone form. GST, a isoflavonoid, is a specific inhibitor of protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) 14 and it induces ΔΨm change, caspase-3 activation, and PARP cleavage. Furthermore, GST is a powerful inhibitor of NF-κB and Akt signaling pathways, both of which are important for cell survival. 15

In the present study, we demonstrated that APG, EGC, EGCG and GST induce apoptosis in human glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells but not in human normal astrocytes (HNA). We also explored that these flavonoids induced apoptosis with increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, loss of ΔΨm, and activation of kinases and proteases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Treatments

Human glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). We purchased passage number 1 of the HNA of human brain tissue from ScienCell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA). We grew the HNA in our laboratory and used passage number 3 for monitoring flavonoid-induced cell death, ROS production, and caspase activities. Glioblastoma cells were grown in 75-cm2 flasks containing 10 ml of 1× RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin in a fully-humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C, whereas HNA were grown in DMEM/F12 medium with 15 mM HEPES, pyridoxine, and NaHCO3 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), supplemented with 2% Sato's components, 1% penicillin and streptomycin (GIBCO-Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), and 2% heat-inactivated FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT). Prior to drug treatments, the cells were starved in medium supplemented with 1% FBS for 24 h. Dose-response studies were conducted to determine the suitable concentration of the drugs used in the experiments. Cells were treated with 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, and 50 µM GST for 24 h for induction of apoptosis. Following treatments, cells were used for determination of the mechanisms of apoptosis.

Wright Staining and ApopTag Assay

Cells from each treatment were washed with 1×PBS, pH 7.4, and sedimented onto the microscopic slide and fixed. The morphological (Wright staining) and biochemical (ApopTag assay) features of apoptosis were examined, as we described previously.16–17 After Wright staining and ApopTag assay, cells were counted under the light microscope to determine percentage of apoptosis.

Fura-2 Assay for Determination of Intracellular Free [Ca2+]

Level of intracellular free [Ca2+] was measured using the fluorescence Ca2+ indicator fura-2/AM, as we described previously.16–18 The value of Kd, a cell-specific constant, was determined experimentally to be 0.387 µM for the T98G cells and 0.476 µM for the U87MG cells, using standards of the Calcium Calibration Buffer Kit with Magnesium (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Analysis of mRNA Expression

Extraction of total RNA, qualitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and agarose gel electrophoresis were performed as we described previously.18 For real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments, the cells from all treatments were homogenized and total RNA samples were extracted according to the RNAwiz protocol (Ambion, Austin, TX). In each reaction, 1 µg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Both bax and bcl-2 mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR in ABI 7000 Prism (Applied Biosystems), using the manufacturer's suggested protocol. At the end of the runs, melting curves were obtained to make sure that there were no primer-dimer artifacts. The products were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis analysis as well. The thereshold cycle values were calculated with the standard software (Applied Biosystems) and quantitative fold changes in mRNA were determined relative to β-actin in each treatment group. All primers (Table 1) for RT-PCR experiments were designed using Oligo software (National Biosciences, Plymouth, MN). The level of β-actin gene expression served as an internal control.

TABLE 1.

Human Primers Used to Determine Levels of mRNA Expression of Specific Genes

| Gene | Primer sequence | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | Sense: 5’-TAT CCC TGT ACG CCT CT-3’ | 460 |

| Antisense: 5’-AGG TCT TTG CGG ATG T-3’ | ||

| baxα | Sense: 5’-AAG AAG CTG AGC GAG TGT-3’ | 265 |

| Antisense: 5’-GGA GGA AGT CCA ATG TC-3’ | ||

| bcl-2α | Sense: 5’-CTT CTC CCG CCG CTA C-3’ | 306 |

| Antisense: 5’-CTG GGG CCG TAC AGT TC-3’ | ||

| BIRC-2 | Sense: 5′-CAG AAA GGA GTC TTG CTC GTG-3′ | 536 |

| Antisense: 5′-CCG GTG TTC TGA CAT AGC ATC-3′ | ||

| BIRC-3 | Sense: 5′-GGG AAC CGA AGG ATA ATG CT-3′ | 368 |

| Antisense: 5′-ACT GGC TTG AAC TTG ACG GAT-3′ | ||

| BIRC-4 | Sense: 5′-AAT GCT GCT TTG GAT GAC CTG-3′ | 470 |

| Antisense: 5′-ACC TGT ACT CAG CAG GTA CTG-3′ | ||

| BIRC-5 | Sense: 5′-GCC CCA CTG AGA ACG-3′ | 302 |

| Antisense: 5′-CCA GAG GCC TCA ATC C-3′ | ||

| Antisense: 5′-GCC ATC CGC CTT AGA A-3′ |

Antibodies

Monoclonal antibody against β-actin (Sigma) was used to standardize cytosolic protein loading on the SDS-PAGE. Anti-cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV (COX4) antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to standardize the mitochondrial protein level. COX4 is a membrane protein in the inner mitochondrial membrane and it remains in the mitochondria regardless of activation of apoptosis. 16–17 Antibodies against α-spectrin (Affiniti, Exeter, UK), and phospho-p38 MAPK (Promega, Madison, WI), were also used. All other primary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA) and Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ). The secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (ICN Biomedicals, aurora, OH) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (ICN Biomedicals).

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as we described previously. 16–17 The isolation of cytosolic, mitochondrial, and nuclear fractions were performed by standard procedures. 16–17 Cytochrome c in the supernatants and pellets and also CAD in nuclear fractions were analyzed by Western blotting. The autoradiograms were scanned using Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, Seattle, WA) and optical density (OD) of each band was determined using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Determination of ROS Production

The fluorescent probe 2',7’-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF-DA) was used for assessment of intracellular ROS production. This is a reliable method for measurement of intracellular ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical, and hydroperoxides.19 Briefly, cells were seeded (1×105 cells/well) in 6-well culture plates. Next day, cells were washed twice with Hank's balanced salt solution (GIBCO-Invitrogen) and loaded with 1 ml of 1×RPMI containing 5 µM of DCF-DA and different concentrations of APG, EGC, EGCG, or GST. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 30 to 1440 min and the fluorescence intensity was measured at 530 nm after excitation at 480 nm in Spectramax Gemini XPS (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The increase in fluorescence intensity was used to assess the generation of net intracellular ROS.

Change in ΔΨm

Loss of ΔΨm was measured by using the fluorescent probe JC-1. Control cells and cells treated with APG, EGC, EGCG, or GST were incubated in medium containing 5 µg/ml JC-1 during treatment from 0.5 h to 24 h (30 min to 1440 min).19 After being stained, the cells were washed twice with PBS. When excited at 488 nm, the fluorescence emission of JC-1 was measured at wavelengths corresponding to its monomer (530 ± 15 nm) and J aggregate (>590 nm) forms. Fluorescence was measured in a fluorescent plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Colorimetric Assays for Caspase Activities

Measurements of caspase activities in cells were performed using the commercially available caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3 assay kits (Sigma). The colorimetric assays were based on the hydrolysis of the Ac-IETD-pNA by caspase-8, Ac-LEHD-pNA by caspase-9, and Ac-DEVD-pNA by caspase-3, resulting in the release of the p-nitroaniline (pNA) moiety. Proteolytic reactions were carried out in extraction buffer containing 200 µg of cytosolic protein extract and 40 µM Ac-IETD-pNA, 40 µM Ac-LEHD-pNA, or 40 µM Ac-DEVD-pNA. The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 2 h and the formation of pNA was measured at 405 nm in a colorimeter. The concentration of the pNA released from the substrate was calculated from the absorbance values. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Trypan Blue Dye Exclusion Assay after Pretreatment with Inhibitors

Loss of membrane integrity was determined on the basis of inability of cells to exclude the vital dye trypan blue. For inhibitor studies, cells were cultured as described before and either left untreated or were pretreated (1 h) with 5 µM Ascorbic acid (Asc), 10 µM caspase-8 inhibitor II, 10 µM calpeptin, 10 µM caspase-9 inhibitor I, and 10 µM caspase-3 inhibitor IV. After 24 h, cells were removed from each treatment, diluted (1:1) with trypan blue (Sigma) and counted (at least 600 cells) for calculation of percentage of residual cell viability.

Statistical Analysis

All results obtained from different treatments were analyzed using StatView software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). Data were expressed as mean + standard error of mean (SEM) of separate experiments (n≥3) and compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher’s post hoc test. Significant difference between control and flavonoid (APG, EGC, EGCG, or GST) treatment was indicated by * P<0.05 or ** P<0.01. Significant difference between flavonoid (APG, EGC, EGCG, or GST) treatment and inhibitor pretreatment (1 h) + flavonoid (APG, EGC, EGCG, or GST) treatment was indicated by # P<0.05 or ## P<0.01.

RESULTS

Morphological and Biochemical Features of Apoptotic Death

We examined morphological and biochemical features of apoptotic death (Fig. 1). Treatment of T98G and U87MG cells with 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, or 50 µM GST increased apoptotic cells, based on morphological (Wright staining) and biochemical (ApopTag assay) features (Fig. 1A and 1B). Quantitation based on ApopTag assay indicated that treatment of cells with a flavonoid significantly increased apoptosis (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Morphological and biochemical features of apoptosis in T98G and U87MG cells. Treatments (24 h): control (CON), 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, and 50 µM GST. (A) Wright staining. (B) ApopTag assay. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. (C) Bar diagram to show percent apoptosis based on ApopTag assay.

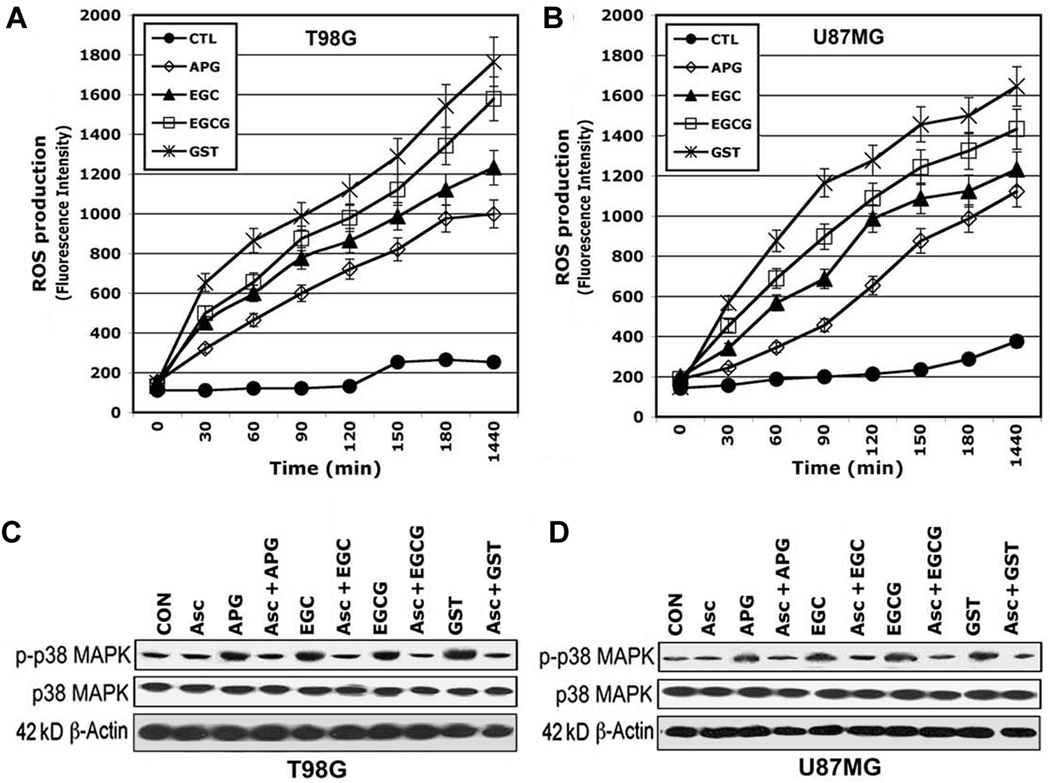

Flavonoids Induced ROS Production and p38 MAPK Phosphorylation for Apoptosis

We determined ROS production and p38 MAPK phosphorylation after the treatments (Fig. 2). To examine ROS production in apoptosis, we measured fluorescence intensity (as a measure of ROS production) resulting from the oxidation of dichlorofluorescin (DCF) in T98G and U87MG cells following exposure to a flavonoid (APG, EGC, EGCG, or GST). Time-dependently, flavonoid treatment promoted the oxidation of DCF in T98G (Fig. 2A) and U87MG (Fig. 2B) cells and addition of 5 µM ascorbic acid (Asc) pretreatment completely blocked ROS production (data not shown). The results suggested that these flavonoids induced apoptosis by a mechanism that required increase in intracellular ROS levels. Western blotting demonstrated that treatment with flavonoid increased phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (p-p38 MAPK) in T98G (Fig. 2C) and U87MG (Fig. 2D) cells. Pretreatment with 5 µM Asc (an anti-oxidant) completely blocked an increase in p-p38 MAPK (Fig. 2C and 2D), indicating involvement of ROS in generation of p-p38 MAPK. We did not see any change in p38 MAPK due to treatments. Treatment with 4-(4-fluoropheny)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)-1H imidazole (SB203580), the specific inhibitor of p-p38 MAPK has previously been reported to show no inhibitory action on p42/44 MAPK and JNK1.20 We found that pretreatment of cells with 5 µM SB203580 almost completely blocked apoptostic death (data not shown). Thus, ROS was required for generation of p-p38 MAPK for apoptosis following exposure to flavonoids.

FIGURE 2.

Determination of ROS production and p38 MAPK phosphorylation in T98G and U87MG cells. Treatments (0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, and 1440 min) in the presence of 5 µM 2,7-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF-DA): control (CON), 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, and 50 µM GST. (A) ROS production in T98G cells. (B) ROS production in U87MG cells. Western blotting to show levels of phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (p-p38 MAPK), p38 MAPK, and β-actin in (C) T98G cells and (D) U87MG cells after the treatments (24 h): control (CON), 10 µM ascorbic acid (Asc), 50 µM APG, 10 µM Asc (1-h pretreatment) + 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 10 µM Asc (1-h pretreatment) + 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, 10 µM Asc (1-h pretreatment) + 50 µM EGCG, 50 µM GST and 10 µM Asc (1-h pretreatment) + 50 µM GST. Pretreatment with Asc prevented formation of p-p38 MAPK.

Flavonoids Activated JNK1 and Suppressed Expression of Anti-apoptotic and Inflammatory Proteins

The activative form of JNK1 is phosphorylated JNK1 (p-JNK1) that regulates the transcription of several genes for cell death. Our Western blotting revealed an increase in 46 kD p-JNK1 following treatment with a flavonoid (Fig. 3). The involvement of activated JNK1 pathway in cell death process was confirmed in our experiments using cell-permeable JNK inhibitor I. Pretreatment of cells with 10 µM JNK inhibitor I provided protection from flavonoid (APG, EGC, EGCG, or GST) mediated cell death (data not shown), indicating involvement of JNK1 pathway in cell death. Our Western blotting also showed decreases in 60 kD p-Akt (phosphorylation of Akt at Ser-473) and 26 kD Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic protein) 21 in glioblastoma cells after treatment with flavonoids (Fig. 3). Almost uniform expression of total 60 kD Akt was detected in treated cells. Thus, our results showed suppression of Akt and Bcl-2 survival pathways during apoptosis. Since nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) are involved in the inflammation and potentiation of cell growth in human glioblastoma, we examined expression of NF-κB and COX-2 after exposure to flavonoids. Our results demonstrated down regulation of 65 kD NF-κB and 70 kD COX-2. β-Actin expression was monitored to ensure that equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane.

FIGURE 3.

Western blotting for the levels of p-JNK1, survival factors (p-Akt and p-Bcl-2), and inflammatory factors (NF-κB and COX-2) in T98G and U87MG cells. Treatments (24 h): control (CON), 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, and 50 µM GST. Protein levels of p-JNK1, p-Akt, total Akt, Bcl-2, NF-κB, COX-2, and β-actin.

EGC and EGCG Induced Caspase-8 Activation and Proteolytic Cleavage of Bid

To determine the involvement of death receptor pathway of apoptosis, we examined activation and activity of caspase-8 in glioblastoma cells following treatments (Fig. 4). Our results showed an increase in active 18 kD caspase-8 band in T98G and U87MG cells due to treatment with EGC and EGCG (Fig. 4A). But we did not observe any increase in active 18 kD caspase-8 band in cells treated with APG and GST (Fig. 4A). β-Actin expression was monitored to ensure that equal amount of cytosolic protein was loaded in each lane. Caspase-8 activation induced proteolytic cleavage of Bid to tBid, which could translocate from cytosol to mitochondrial membrane to stimulate efficient oligomerization of Bax and thereby activate the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. We examined the level of tBid in mitochondrial fraction and also monitored level of COX4 as a mitochondrial internal control (Fig. 4A). We found dramatic increase in tBid in mitochondria in both T98G and U87MG cells treated with EGC and EGCG (Fig. 4A), indicating increase in caspase-8 activity. Further, colorimetric assay showed significant increase in total caspase-8 activity in cells treated with EGC and EGCG (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Determination of caspase-8 activation and activity in T98G and U87MG cells. Treatments (24 h): control (CON), 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, and 50 µM GST. (A) Western blotting to show levels of caspase-8, β-actin, tBid, and COX4. (B) Colorimetric determination of caspase-8 activity.

Apoptosis via Mitochondrial Pathway

Apoptosis may occur with involvement of mitochondria, which release cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors during different forms of cellular stress.22 We examined the involvement of mitochondrial events in apoptosis in glioblastoma cells after the treatments (Fig. 5). Treatment of cells with APG, EGC, EGCG and GST increased Bax but decreased Bcl-2 expression at mRNA and protein levels(Fig. 5A). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments were carried out to determine the relative mRNA levels of the bax and bcl-2 genes. Expression of β-actin was used to normalize the values. Similar changes in mRNA levels were observed in both qualitative and quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5A). Based on Western blotting, we measured the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio, which was significantly increased following treatments (Fig. 5B). Mitochondrial damage is often associated with loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), which is readily measured using the JC-1 staining.13 Control T98G and U87MG cells showed a high JC-1 ratio (590 nm/530 nm). After treatments, the mean red and green fluorescence ratio in the mitochondria dropped slowly in a biphasic way, indicating the collapse of the ΔΨm during apoptosis in T98G (Fig. 5C) and U87MG (Fig. 5D) cells. This collapse of ΔΨm was associated with mitochondrial release of 15 kD cytochrome c and 23 kD Smac into the cytosol (Fig. 5E) to cause activation of caspases. We used COX4 as a loading control for mitochondrial protein. We observed an increase in active 37 kD caspase-9 fragment in cells following treatments (Fig. 5E). β-Actin expression was used to ensure that an equal amount of cytosolic protein was loaded in each lane. A colorimetric assay confirmed a significant increase in total caspase-9 activity for apoptosis in cells following treatments (Fig. 5F). In response to apoptotic stimuli, Smac is released from mitochondria into the cytosol to block inhibitory function of the baculoviral inhibitor-of-apoptosis repeat containing (BIRC) proteins so as to promote caspase-9 activation.17 We examined the expression of BIRC molecules at mRNA (Fig. 5G) and protein (Fig. 5H) levels to understand their roles in apoptosis in T98G and U87MG cells after the treatments. The decreases in BIRC-2 to BIRC-5 at mRNA and protein levels correlated well with the increases in cytosolic Smac. Together, these results suggested that loss of ΔΨm, mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and Smac into the cytosol, and subsequent activation of caspase-9 played key roles in apoptosis in glioblastoma cells.

FIGURE 5.

Examination of components involved in mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis in T98G and U87MG cells. Treatments (24 h): control (CON), 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, and 50 µM GST. (A) Determination of mRNA levels of bax and bcl-2 by qualitative RT-PCR as well as real-time quantitative RT-PCR. (B) Western blotting for examination of Bax and Bcl-2 expression at protein levels and determination of Bax:Bcl-2 ratio based on Western blotting. JC-1 ratio (590 nm/530 nm) in (C) T98G and (D) U87MG cells after the treatments for different times (30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 300, 360, 420, 480, 540, 600, 660, and 1440 min). (E) Western blotting to show levels of cytochrome c, Smac, COX4, caspase-9, and β-actin. (F) Determination of caspase-9 activity using a colorimetric assay. (G) Qualitative RT-PCR and (H) Western blotting to show mRNA and protein levels of BIRC-2 to BIRC-5 and β-actin.

Increase in Intracellular Free [Ca2+] and Activation of Caspase-4, Calpain, and Caspase-3 for Apoptosis

We explored the contribution of intracellular free [Ca2+], capsase-4, calpain, and caspse-3 to apoptosis in glioblastoma cells (Fig. 6). Fura-2 assay showed significant increases intracellular free [Ca2+] in T98G and U87MG cells following treatments with the flavonoids (Fig. 6A). These results suggested a role for intracellular free [Ca2+] in apoptosis. Human caspase-4 is localized to endoplamic reticulm (ER) membrane and activated during ER stress. 23 We found involvement of ER stress and activation of caspase-4 during apoptosis when cells were treated with the flavonoids (Fig. 6B). The Ca2+-dependent protease calpain was overexpressed and activated leading to degradation of calpastatin, the endogenous inhibitor of calpain, in glioblastoma cells after exposure to the flavonoids (Fig. 6B). The final executioner caspase-3 was also overexpressed and activated for mediation of apoptosis (Fig. 6B). Degradation of 270 kD α-spectrin to 145 kD spectrin breakdown product (SBDP) and 120 kD SBDP has been attributed to proteolytic activities of calpain and caspase-3, respectively.16–19 Cells treated with flavonoids produced 145 kD SBDP and 120 kD SBDP (Fig. 6B), indicating increased activities of calpain and caspase-3, respectively. Increased activity of caspase-3 also cleaved inhibitor of caspase-activated DNase (ICAD) to release and translocate CAD to the nucleus (Fig. 6B) to cause degradation of nuclear DNA. Almost uniform expression of β-actin served as a loading control for cytosolic proteins. We stained one set of gel with Coomassie Blue to ensure loading of equal amounts of nuclear proteins in all lanes (Fig. 6B). A colorimetric assay indicated very significant increases in total caspase-3 activity in glioblastoma cells after exposure to flavonoids (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Examination of increase in intracellular free [Ca2+] and activation of caspase-4, calpain, and caspase-3 in T98G and U87MG cells. Treatments (24 h): control (CON), 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, and 50 µM GST. (A) Determination of intracellular free [Ca2+]. (B) Western blotting to show levels of caspase-4, inactive and active calpain, calpastatin, spectrin breakdown product (SBDP), inactive and active caspase-3, ICAD, CAD, and β-actin. (C) Determination of caspase-3 activity by a colorimetric assay.

Prevention of Cell Death by Pretreatment with different inhibitors

Pretreatment of glioblastoma cells for 1 h with Asc and caspase-3 inhibitor IV inhibited cell death due to treatments with flavonoids (Fig. 7). In contrast, caspase-9 inhibitor I showed partial inhibitory effect. Pretreatment of cells with calpeptin (calpain inhibitor) blocked cell death in APG and GST treatments, whereas caspase-8 inhibitor II blocked cell death in EGC and EGCG treatments. Blocking of more than 60% cell death occurred by calpeptin in cells treated with EGC and EGCG, and by caspase-8 inhibitor II in cells treated with APG and GST (Fig. 7). These results indicated the roles of ROS production and also calpain and caspases activities in cell death.

FIGURE 7.

Pretreatment with selective inhibitors prevented flavonoid mediated cell death in T98G and U87MG cells. Treatments (24 h): control (CON), 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, and 50 µM GST without any inhibitor and with 1-h pretreatment with 5 µM Asc, 10 µM caspase-8 inhibitor II, 10 µM caspase-9 inhibitor I, 10 µM calpeptin (calpain-specific inhibitor), or 10 µM caspase-3 inhibitor IV. Determination of percent viability in (A) T98G cells and (B) U87MG cells.

Human Normal Astrocytes (HNA) Remained Resistant to Flavonoids

We examined the effects flavonoids on HNA (Fig. 8). Residual cell viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion test under the light microscope following treatment of HNA with the flavonoids for 24 h. Compared with control cells, cells treated with flavonoids did not show any significant change in viability (Fig. 8A). These results demonstrated that APG, EGC, EGCG, and GST were cytotoxic to glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells but not to HNA. Time-dependently, flavonoid treatment did not promote considerable oxidation of DCF in HNA (Fig. 8B). The results suggested that flavonoids did not sufficiently increase in intracellular ROS levels in HNA to induce cell death. Colorimetric assays showed insignificant changes in activities of caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3 in HNA following treatment with flavonoids (Fig. 8C). These results indicated that HNA did not commit apoptosis due to exposure to flavonoids.

FIGURE 8.

Effects of flavonoids on human normal astrocytes (HNA). Treatments (24 h): control (CON), 50 µM APG, 50 µM EGC, 50 µM EGCG, and 50 µM GST. (A) Determination of percent cell viability by trypan blue dye exclusion test. (B) Determination of ROS production in HNA at different time intervals (0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, and 1440 min). (C) Colorimetric assays for determination of the caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3 activities.

DISCUSSION

Flavonoids have emerged as potential therapeutic agents for treatment of cancers, especially due to their ability to induce apoptosis. In this investigation, we demonstrated that flavonoids (APG, EGC, EGCG and GST) induced apoptosis in human glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells (Figs. 1–7) without affecting the normal astrocytes (Fig. 8). We explored the molecular mechanisms of induction of apoptosis in glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells following exposure to these flavonoids.

Diverse chemotherapeutic agents can induce apoptosis in cancer cells via death receptor and mitochondrial pathways due to increased ROS generation. 24 Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK induces apoptosis, whereas phosphorylation of p42/44 MAPK exerts cytoprotective effects.22, 23 The addition of Asc completely blocked the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, suggesting an involvement of ROS in phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (Fig. 2). Thus, production of ROS provided a signal for selective phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and induction of apoptosis in glioblastoma cells after treatment with flavonoids.

Our data showed activation or phosphorylation of the JNK1 (p-JNK1) in flavonoid treated glioblastoma cells, which correlated with production of ROS, suggesting an essential role of p-JNK1 in induction of apoptosis (Fig. 3). We also observed that flavonoids down regulated expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and activation of the key anti-apoptotic kinase Akt (Fig. 3). NF-κB and COX-2 are known to be involved in the inflammatory responses. Dysregulation of the NF-κB and COX-2 pathways play important roles in the development of various cancers. 24, 25 Our results demonstrated that flavonoids suppressed expression of both NF-κB and COX-2 in glioblstoma cells (Fig. 3).

Cleavage of Bid to tBid as a result of caspase-8 activation promotes Bax mediated mitochondrial release of cytochrome c. We found caspase-8 activation and also its activity in the cleavage of Bid to tBid in T98G and U87MG cells treated with EGC and EGCG but not with APG and GST (Fig. 4). Translocation of tBid from cytosol to mitochondrial membrane could stimulate more efficient oligomerization of Bax for inducing the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. The relative levels of Bax (pro-apoptotic) and Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic) in mitochondria determine the fate of cells. Heterodimerization of Bax with Bcl-2 prevents apoptosis while Bax homodimerization triggers apoptotic process with the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and Smac into the cytosol. Following flavonoid treatments, increase in Bax:Bcl-2 ratio and decrease in ΔΨm triggered accumulation of cytosolic cytochrome c for increasing activation and activity of caspase-9 (Fig. 5). Because cytosolic Smac could suppress survival effects of BIRC proteins, we examined alteration in the levels of BIRC proteins in T98G and U87MG cells after treatment with flavonoids and found that some of these survival proteins (BIRC-2 to BIRC-5) were down regulated for promoting apoptosis (Fig. 5).

Our findings support a direct relationship among increases in intracellular free [Ca2+], ER stress (caspase-4 activation), calpain activation, and caspase-3 activation for apoptosis in glioblastoma cells following exposure to flavonoids (Fig. 6). Increased calpain activity cleaved calpastatin and also generated 145 SBDP while increased caspase-3 activity generated 120 kD SBDP and cleaved ICAD to release and translocate CAD to the nucleus (Fig. 6). We used specific inhibitors to confirm that glioblastoma cells committed cell death due to ROS production and activation of caspase-8, caspase-9, calpain and caspase-3 (Fig. 7). Based on our results, we suggest that APG, EGC, EGCG, and GST activate multiple pathways for induction of apoptosis in glioblastoma cells, but not in HNA. It should be noted that flavonoids do not require a p53-dependent pathway for mediation of apoptosis because they are capable of inducing apoptosis in both T98G (mutant p53) and U87MG (wild-type p53) cells.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that flavonoids (APG, EGC, EGCG, and GST) induced apoptosis in T98G and U87MG cells via multiple mechanisms including increase in ROS production, activation of kinases, down regulation of survival pathways and inflammatory factors, and activation death receptor and mitochondrial pathways. Our data suggested the following relative potency of these flavonoids (at 50 µM): APG < EGC < EGCG < GST for induction of apoptosis in T98G and U87MG cells. Finally, these flavonoids induced apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells but not in normal astrocytes, indicating their selective action for controlling glioblastoma. This approach of using flavonoids for induction of apoptosis specifically in glioblastoma cells is particularly appealing since currently a major obstacle in cancer therapy is extensive drug toxicity to the normal cells.

Acknowledgements

This investigation was supported in part by the R01 grants (CA-91460 and NS-57811) from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) to Swapan K. Ray.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanchez-Martin M. Brain tumour stem cells: implications for cancer therapy and regenerative medicine. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2008;3:197–207. doi: 10.2174/157488808785740370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad N, Cheng P, Mukhtar H. Cell cycle dysregulation by green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Biochem. Biophys Res Commun. 2000;275:328–334. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad N, Feyes DK, Nieminen AL, et al. Green tea constituent epigallocatechin-3-gallate and induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human carcinoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1881–1886. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.24.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown A, Jolly P, Wei H. Genistein modulates Glioblastoma cell proliferation and differentiation through induction of apoptosis and regulation of tyrosine kinase activity and N-myc expression. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:991–997. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.6.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung LY, Cheung TC, Kong SK, et al. Induction of apoptosis by green tea catechins in human prostate cancer DU145 cells. Life Sci. 2001;68:1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)01020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantinou A, Huberman E. Genistein as an inducer of tumor cell differentiation: possible mechanisms of action. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995;208:109–115. doi: 10.3181/00379727-208-43841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Formica JV, Regelson W. Review of the biology of quercetin and related bioflavonoids. Food chem Toxicol. 1995;33:1061–1080. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(95)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta S, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Involvement of nuclear factor-kappa B, Bax and Bcl-2 in induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by apigenin in human prostate carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:3727–3738. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos S. Cancer chemoprevention and chemotherapy: dietary polyphenols and signaling pathways. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:507–526. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta S, Hussain T, Mukhtar H. Molecular pathway for (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of human prostate carcinoma cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;410:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vargo MA, Voss OH, Poustka F, et al. Apigenin-induced-apoptosis is mediated by the activation of PKCδ and caspases in leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:681–692. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosengren RJ. Catechins and the treatment of breast cancer: possible utility and mechanistic targets. Idrugs. 2003;6:1073–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saeki K, Kobayashi N, Inazawa Y, et al. Oxidation-triggered c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways for apoptosis in human leukaemic cells stimulated by epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): a distinct pathway from those of chemically induced and receptor-mediated apoptosis. Biochem J. 2002;368:705–720. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paillart C, Carlier E, Guedin D, et al. Direct block of voltage-sensitive sodium channels by genistein, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:521–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Sarkar FH. Inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB activation in PC3 cells by genistein is mediated via Akt signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2369–2377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das A, Banik NL, Ray SK. Garlic compounds generated reactive oxygen species leading to activation of stress kinases and cysteine proteases for apoptosis in human glioblastoma T98G and U87MG cells. Cancer. 2007;110:1083–1095. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das A, Banik NL, Ray SK. Mechanism of apoptosis with the involvement of proteolytic activities of calpain and caspases in human malignant neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells exposed to flavonoids. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2575–2585. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray SK, Patel SJ, Welsh CT, et al. Molecular evidence of apoptotic death in malignant brain tumors including glioblastoma multiforme: upregulation of calpain and caspase-3. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:197–206. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid AB, Kurten RC, Mc Cullough SS, et al. Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity: role of oxidative stress and mitochondrial permeability transition in freshly isolated mouse hepatocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:509–516. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Junghae M, Raynes JG. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase attenuates Leishmania donovani infection in macrophages. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5026–5035. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5026-5035.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosser CJ, Reyes AO, Vakar-Lopez F, et al. p53 and Bcl-2 are over-expressed in localized radio-recurrent carcinoma of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04468-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werdehausen R, Braun S, Essmann F, et al. Lidocaine induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway independently of death receptor signaling. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:136–143. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000268389.39436.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hitomi J, Katayama T, Eguchi Y, et al. Involvement of caspase-4 in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and A-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:347–356. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stan AC, Casares S, Radu D, et al. Doxorubicin-induced cell death in highly invasive human gliomas. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:941–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.St-Germain ME, Gagnon V, Parent S, et al. Regulation of COX-2 protein expression by Akt in endometrial cancer cells is mediated through NF-κB/IκB pathway. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]