Abstract

Aim:

To assess the various epidemiological parameters that influence the causation of trauma as well as the consequent morbidity and mortality in the pediatric age group.

Materials and Methods:

A prospective study of 791 patients of less than 12 years age, was carried out over a period of 1 year (August 2009 to July 2010), and pediatric trauma trends, with regards to the following parameters were assessed: Age group, sex, mode of trauma, type of injury, place where the trauma occurred and the overall mortality as well as mortality.

Results:

Overall trauma was most common in the school-going age group (6-12 years), with male children outnumbering females in the ratio of 1.9:1. It was observed that orthopedic injuries were the most frequent (37.8%) type of injuries, whereas fall from height (39.4%), road traffic accident (27.8%) and burns (15.2%) were the next most common modes of trauma. Home was found out to be the place where maximum trauma occurred (51.8%). Maximum injuries happened unintentionally (98.4%). Overall mortality was found out to be 6.4% (n = 51).

Conclusions:

By knowing the epidemiology of pediatric trauma, we conclude that majority of pediatric injuries are preventable and pediatric epidemiological trends differ from those in adults. Therefore, preventive strategies should be made in pediatric patients on the basis of these epidemiological trends.

Keywords: Fall, injury, pediatric trauma, road traffic accidents

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric trauma is a very significant cause of mortality and disability, being responsible for more deaths than all diseases combined.[1] The burden of child injuries in India is not clearly known because our knowledge is inadequate about their epidemiology. As per National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report of 2006, there were 22,766 deaths (<14 years) due to injuries among children.[2] There are very few studies from developing countries discussing the epidemiology of pediatric trauma. Our study aims to determine the frequency of various types of childhood injuries in different sex and age groups and also to find out the various modes and place of trauma among study subjects and their distribution according to different age and sex groups. It also gives an idea about the relative mortality in various types of childhood injuries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective study conducted at a tertiary care hospital over a 12-month period. A total of 791 patients (age up to 12 years) with trauma were admitted between August 2009 and July 2010. Isolated pediatric ophthalmic trauma, drowning as well as parental psychiatric disorders responsible for pediatric trauma, such as battered baby syndrome, were excluded from our study.

A detailed history taking (from parents/relatives/children) and examination was done and all patients were assessed with regards to their age, sex, mode of trauma/injury, type of injury, site of trauma, place of trauma, and mortality. The children were classified according to age as: Infants (up to 1 year), toddlers (1-3 years), preschool (3-6 years) and school-age children (6-12 years). Modes of trauma were divided as: Fall from height, road traffic accident (RTA), burn, sports related, assault (sexual, sharp, blunt), poisoning, bites and stings. The types of injury were divided into subgroups: Orthopedic, head, burns, abdomen, poisoning, bites and sting, chest, poly trauma and genital injuries. The places of trauma were divided into the following: Home, road, farm, school/playground or park and others. The mortality data were shown according to different age groups as described earlier and according to the mode of injury.

RESULTS

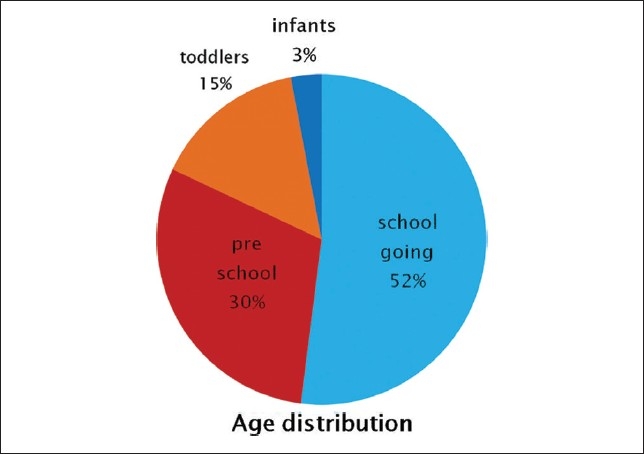

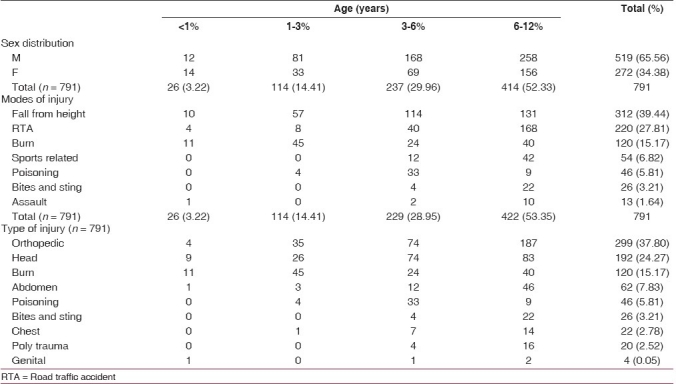

Out of the total 6102 pediatric patients admitted, the cause of admission for 791 patients was trauma. The mean age of presentation was 6.3 years. School-going children were the most commonly injured (52.33%) [Figure 1]. Males outnumbered females in a ratio of 1.9:1. Children mostly suffered from orthopedic injuries (37.80%). Among the non orthopedic injuries, head and abdominal injury was the most common seen in the school-going children. While in burns, toddler group was the most commonly affected age group [Table 1]. Fall from height (39.44%), RTAs (27.83%) and burns (15.18%) were the most common mode of injury leading to pediatric trauma [Table 1]. Most of the cases (98.36%) were injured unintentionally. Thirteen cases (1.64%) were injured intentionally. Out of the 13 cases, 8 were injured by blunt object, 3 by sharp object and 2 cases were sexually assaulted.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of trauma

Table 1.

Modes and type of injuries among children of different age groups

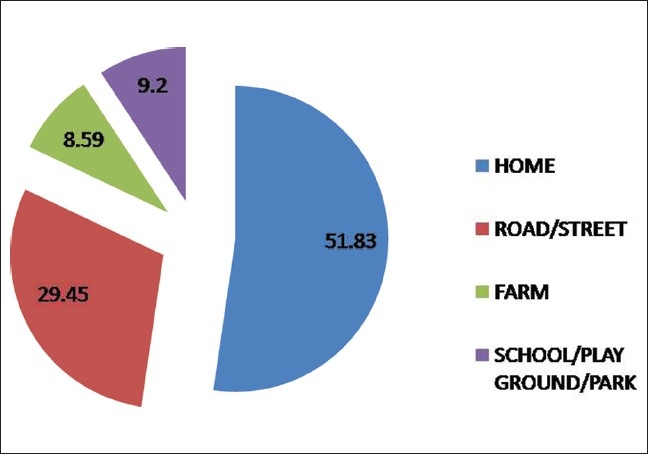

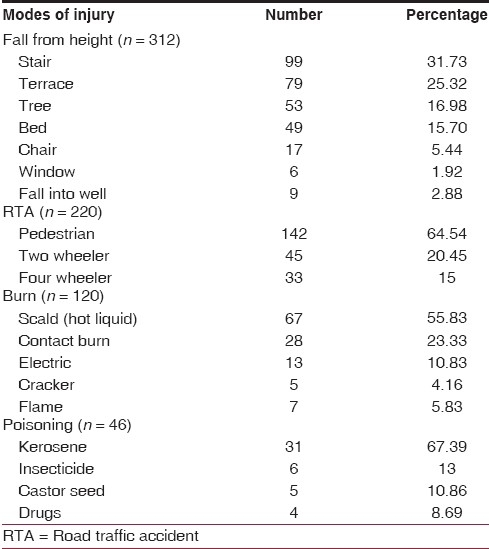

In our study we found the home to be the most common place of injury [Figure 2]. The most common cause of injury among all traumatized children was a fall injury. It affected mostly school-going children. Around 59% of all falls occurred at home, followed by farms. At home, most of the falls occurred from stairs (31.73%), followed by the terrace (25.32%), whereas at the farm, the most common place of fall was from a tree (16.98%), followed by fall into well (2.88%) [Table 2]. RTA was the second most common mode of injury. School-going children were affected the most. Of 220 children involved in RTA, 64.54% were pedestrians, 20.45% were two-wheeler passengers and 15% were four-wheeler passengers [Table 2].

Figure 2.

Places of trauma

Table 2.

Characteristics of injuries due to fall, road traffic accident, burn and poisoning

Out of total 120 burn patients, 45 (37.5%) patients belonged to the toddler age group. Burns due to scalds (hot liquids) accounted for 55.83% cases, while burns due to flames and electricity accounted for 23.33% and 10.83% of the cases, respectively. Cracker and contact burns were the remaining cause of burn injury [Table 2]. Preschool age group formed the largest group of poisoning victims (71.73%). Most of these victims had ingested kerosene (67.39%) followed by insecticide (13%), castor seed (10.86%) and drugs (8.69%) [Table 2].

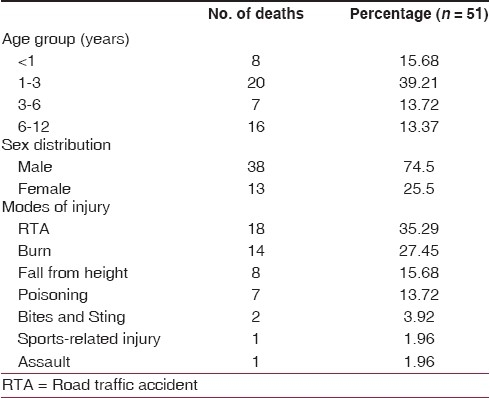

Out of 791 patients admitted, 51 died (6.44%). Children of 1-3 years age group had the highest mortality (39.21%) in their respective age group, followed by infants (15.38%). Males (74.5%) outnumbered females (25.5%) [Table 3]. Our study also revealed RTA as one of the major causes of injury, causing the highest mortality (35.29%), followed by burns (27.45%) and fall from height (15.68%) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Mortality among children of different age groups and with respect to modes of injury

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of trauma in childhood patients was approximately 19.23%. This was probably due to delayed presentation to our tertiary institute (either via referrals or direct admission), or probably due to lack of knowledge and low literacy levels among the parents of these children. Tandon et al.[3] reported a prevalence of 14.2%, and another study done at Naraingarh, India,[4] reported a prevalence of 5.5%.

Many studies have been done from Bangladesh,[5] Iran,[6] Nigeria,[7] Thailand,[8,9] Singapore[10,11] and from major Indian cities,[12–15] and these studies have found boys to be more commonly injured then girls. Home was found to be the most common place of injury, followed by road/street, with falls being the most common mechanism of pediatric trauma. The mean age of presentation in our study was 6.3 years which is in consonance with the above studies.[7,10] In our study too, boys were more commonly hospitalized than girls, probably since in our country, boys are given more freedom as well as free hand to work or play outside their homes. Male to female ratio was 1.9:1 in our study which is similar to the 1.5:1 to 3:1 ratio reported in the above studies.[7,16,17] School-going children (6-12 years) were the most common age group found to be affected in our study, which is also similar to that reported in other previous studies.[6,7,15]

Majority of our injuries occurred at home, followed by road and school/playground. Studies from Trinidad and Tobago, Ethiopia, and Nigeria[7,18,19] all found the home environment to be the most common place for a childhood injury to occur. In our study, falls were the leading cause of trauma in all age groups, followed by RTAs, except in the 6-12 year age group in which falls were the second most common etiology after RTAs. This finding also correlates well with reports from different studies.[20,21] In our study, stairs and terrace were the two most common causes of fall from height, while in a study from Singapore, slipping and fall from bed were the most common causes of falls, once again signifying different epidemiological patterns in different parts of the world.[10] In our study, most of the victims of RTAs were pedestrians, followed by two-wheeler passengers. This finding is similar to that derived from studies done at Maput and Tehran.[6,22]

In our study, a vast majority of burn injuries occurred from hot liquids, followed by flame injuries. Similar results were drawn from studies done in Pakistan and South Africa.[23,24] In our study, kerosene ingestion was the most common cause of poisoning. followed by insecticides and drugs, whereas reports from other countries[25–27] reveal kerosene to be the most common cause followed by drug ingestion and insecticides.

Most mortality in our study occurred in the 1-3 year age group. Bener et al. also reported the same result in his study.[28] Mortality was higher in males. RTA was most common cause of death, followed by burn and fall from height. These results are similar to those of the studies done in developing countries,[29,30] whereas studies from developed countries reveal RTA to be the most common cause of death, followed by gunshot injuries.[31,32]

CONCLUSIONS

This study gives an idea about the epidemiology of pediatric trauma, with 6-12 years age group found to be the most affected and 1-3 years age group found to be the most vulnerable with regards to overall mortality. Home was the most common place of injury, and fall and RTA were the most common mechanisms of injuries. By knowing the epidemiology of pediatric trauma, we conclude that majority of pediatric injuries are preventable and pediatric epidemiological trends differ from those in adults. Therefore, preventive strategies should be made in pediatric patients on the basis of these epidemiological trends. As the saying rightly goes, “Prevention is better than cure”.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krug EG, Sharma GK, Lozano R. The global burden of injuries. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:523–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Crime Records Bureau. Accidental deaths and suicides in India. Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi, Government of India. 2007

- 3.Tandon JN, Kalra A, Kalra K, Sahu SC, Nigam CB, Qureshi GU. Profile of accidents in children. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30:765–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singhi S, Gupta G, Jain V. Comparison of childhood emergency patients in a tertiary care hospital vs a community hospital. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhury SM, Rahman A, Mashreky SR, Giashuddin SM, Svanström L, Hörte LG, et al. The horizon of unintentional injuries among children in low-income setting: An Overview from Bangladesh health and injury survey. J Environ Public Health. 2009;2009:435403. doi: 10.1155/2009/435403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karbakhsh M, Zargar M, Zarei MR, Khaji A. Childhood injuries in Tehran: A review of 1281 cases. Turk J Pediatr. 2008;50:317–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adesunkanmi AR, Oginni LM, Oyelami AO, Badru OS. Epidemiology of childhood injury. J Trauma. 1998;44:506–12. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199803000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruangkanchansaasetr S. Childhood accidents. J Med Assoc Thai. 1989;72:144–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozik CA, Suntayakorn S, Vaughn DW, Suntayakorn C, Snitbhan R, Innis BL. Causes of death and unintentional injury among school children in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;30:129–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong ME, Ooi SB, Manning PG. A review of 2,517 childhood injuries seen in Singapore emergency department in 1999- mechanism and injury prevention suggestions. Singapore Med J. 2003;44:12–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thein MM, Lee BW, Bun PY. Childhood injuries in Singapore: A community nationwide study. Singapore Med J. 2005;46:103–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulshrestha R, Gaind BN, Talukdar B, Chawla D. Trauma in childhood-past and future. Indian J Pediatr. 1983;50:247–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02752757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sitaraman S, Sharma U, Saxena S, Sogani KC. Accidents in infancy and childhood. Indian Pediatr. 1985;22:815–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma AK, Sarin YK, Manocha S, Agarwal LD, Shukla AK, Zaffar M, et al. Pattern of childhood trauma: Indian perspective. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verma S, Lal N, Lodha R, Murmu L. Childhood trauma profile at a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:168–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith GS, Barss P. Unintentional injuries in developing countries: The epidemiology of a neglected problem. Epidemiol Rev. 1991;13:228–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barss P, Smith GS, Baker SP, Mohan D. Open University Press; 1998. Injury prevention: An international perspective.Epidemiology, Surveillance, and Policy. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirsch TD, Beaudreau RW, Holder YA, Smith GS. Pediatric injuries presenting to an emergency department in a developing country. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1996;12:411–5. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mariam A, Sadik M, Gutema J. Patterns of accidents among children visiting Jimma University Hospital, Southwest of Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2006;44:339–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agran PF, Winn DG, Anderson CL. Surveillance of pediatric injury hospitalizations in Southern California. Inj Prev. 1995;1:234–7. doi: 10.1136/ip.1.4.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Constan E, de laRevilla E, Fernandez G. Accidentesinfantilesattendidos en Los Centros de Salud (Spanish) AtenPrimaria. 1995;16:628. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersburgo DD, Keyes CE, Wright DW, Click LA, Macleod JBA, Sasser SM. The epidemiology of childhood injury in Maputo, Mozambique. Int J Emerg Med. 2010;3:157–63. doi: 10.1007/s12245-010-0182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad M. Pakistani experience of childhood burns in a private setup. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2010;23:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parbhoo A, Louw QA, Grimmer-Somers K. Aprofile of hospital-admitted paediatric burns patients in South Africa. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:165. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manzar N, Saad SM, Manzar B, Fatima SS. Therstudy of etiological and demographic characteristics of acute household accidental poisoning in children – A consecutive case series study from Pakistan. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nhachi CF, Kasilo OM. Household chemicals poisoning admissions in Zimbabwe's main urban centres. Hum ExpToxicol. 1994;13:69–72. doi: 10.1177/0960327194013002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adejuyigbe EA, Onayade AA, Senbanjo IO, Oseni SE. Childhood poisoning at the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2002;11:183–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bener A, Al-Salman KM, Pugh RN. Injury mortality and morbidity among children in the United Arab Emirates. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:175–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1007444109260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adesunkanmi K, Oyelami A. The pattern and outcome ofburn injuries at Wesley Guild Hospital, Ilesha, Nigeria: A review of 156 cases. J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;97:108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onuba O, Udoidiok E. The problems and prevention of burns in developing countries. Burns. 1987;13:382. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(87)90128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vane DW, Shackford SR. Epidemiology of rural traumatic death: A population-based study. J Trauma. 1995;38:867. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dodge CC, Cogbill TH, Miller GJ, Lander-Casper J, Strutt PJ. Gunshot wounds: 10 year experience of a rural referral trauma center. Am Surg. 1994;60:401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]