Abstract

The zebrafish posterior lateral line (pLL) is a sensory system that comprises clusters of mechanosensory organs called neuromasts (NMs) that are stereotypically positioned along the surface of the trunk. The NMs are deposited by a migrating pLL primordium, which is organized into polarized rosettes (proto-NMs). During migration, mature proto-NMs are deposited from the trailing part of the primordium, while progenitor cells in the leading part give rise to new proto-NMs. Wnt signaling is active in the leading zone of the primordium and global Wnt inactivation leads to dramatic disorganization of the primordium and a loss of proto-NM formation. However, the exact cellular events that are regulated by the Wnt pathway are not known. We identified a mutant strain, lef1nl2, that contains a lesion in the Wnt effector gene lef1. lef1nl2 mutants lack posterior NMs and live imaging reveals that rosette renewal fails during later stages of migration. Surprisingly, the overall primordium patterning, as assayed by the expression of various markers, appears unaltered in lef1nl2 mutants. Lineage tracing and mosaic analyses revealed that the leading cells (presumptive progenitors) move out of the primordium and are incorporated into NMs; this results in a decrease in the number of proliferating progenitor cells and eventual primordium disorganization. We concluded that Lef1 function is not required for initial primordium organization or migration, but is necessary for proto-NM renewal during later stages of pLL formation. These findings revealed a novel role for the Wnt signaling pathway during mechanosensory organ formation in zebrafish.

Keywords: Lef1, Lateral line primordium, Progenitor cells, Zebrafish

INTRODUCTION

Collective cell migration is defined as a directional migration of interconnected groups of cells. This process is important during organogenesis and is also displayed by invasive groups of metastatic cells in some cancers (Friedl et al., 2004; Yilmaz and Christofori, 2010). The lateral line (LL) system of zebrafish has proven to be an attractive model for the study of collective cell migration, as it is formed by a migrating group of cells close to the surface of the animal, which makes it accessible to various experimental manipulations (Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 2003; Perlin and Talbot, 2007). The LL system, which senses changes in water currents, consists of discrete mechanosensory organs (neuromasts; NM) distributed across the surface of zebrafish. Each NM is comprised of mechanosensory hair cells and surrounding support cells (Aman and Piotrowski, 2009; Ma and Raible, 2009). The posterior LL (pLL) is formed during the first few days of zebrafish embryonic development by the placode-derived pLL primordium. The pLL primordium consists of ∼100 cells that collectively migrate caudally along the trunk between 22 and 48 hours post-fertilization (hpf), depositing NMs every 5 to 7 somites (Ghysen and Dambly-Chaudiere, 2004; Ghysen and Dambly-Chaudiere, 2007; Sarrazin et al., 2010). During migration, cells in the trailing (rostral) region of the primordium are organized into polarized rosettes (proto-NMs) that will be deposited as NMs. After deposition, a new rosette is formed in the leading (caudal) region of the pLL primordium from a small population of proliferating progenitor cells (Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). At this time the mechanisms regulating progenitor specification and renewal in the primordium are unknown.

The patterning and migration of the primordium are regulated by a network of signaling pathways, including canonical Wnt and FGF (Ma and Raible, 2009). Wnt signaling is active in the leading third of the primordium, which contains progenitor cells and newly forming rosettes. Direct Wnt targets, lef1 and axin2, are expressed in this leading region (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). Expression of the Wnt inhibitor dkk1 in the middle region of the primordium, where polarized cells condense into rosettes, restricts Wnt activity to the leading zone. Both loss and overexpression of Wnt signaling lead to disruptions in rosette organization and NM deposition (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). Active Wnt signaling is necessary for the expression of two FGF ligands, fgf3 and fgf10a, in the leading part of the primordium. The transcript encoding the FGF receptor, fgfr1, is expressed in the trailing zone, where activation of FGF signaling is required for proper patterning and migration of the primordium (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008; Lecaudey et al., 2008; Matsuda and Chitnis, 2010; Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). Overstimulation of Wnt pathway or loss of FGF signaling leads to abnormal primordium patterning, including expansions of leading zone markers (fgf10a, lef1 and axin2) and the loss of a trailing marker (pea3) (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). However, the exact cellular events regulated by these pathways and how they coordinate to accomplish rosette renewal and NM deposition are not known.

Using a forward genetic approach, we sought factors required for rosette renewal during primordium migration. Mutagenesis screening yielded the lef1nl2 mutant, which exhibits premature truncation of the pLL and loss of terminal NMs. In lef1nl2 mutants, primordium migration and NM deposition begin normally, but over time the primordium fails to generate new rosettes and becomes disorganized leaving a small trail of cells beyond the distal-most NM. Positional cloning revealed that lef1nl2 is a mutation in lef1, an effector and target of Wnt signaling. Using live imaging, cell transplantation and lineage analyses, we show that Lef1 functions to regulate the identity of progenitor cells in the leading edge of the primordium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Zebrafish strains

Adult zebrafish were maintained under standard conditions. Embryos from *AB and WIK adults were staged according to standard protocols (Kimmel et al., 1995). The pLL primordium and nerve were visualized using the Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP)zf106 line (Haas and Gilmour, 2006) and the TgBAC(neurod:EGFP)nl1 line (Obholzer et al., 2008), respectively. Wnt/β-catenin signaling was conditionally inhibited using the Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP)w32 line (Stoick-Cooper et al., 2007).

Mutagenesis screen and genetic mapping

The lef1nl2 mutation was identified in a three-generation N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis screen (Mullins et al., 1994; Mullins and Nusslein-Volhard, 1993). Larvae were screened at 4 dpf for loss of NMs using 2-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)-N-ethylpyridinium iodide (DASPEI; Invitrogen) according to the established protocol (Harris et al., 2003). Mature hair cells were labeled with FM1-43 (1:1000; Invitrogen). For genetic mapping, heterozygous carriers of lef1nl2 on a polymorphic *AB/WIK background were intercrossed to produce homozygous, heterozygous and wild-type progeny. Initial chromosome assignment was carried out by bulk segregant analysis of DNA pools from 20 wild-type and 20 mutant individuals. The following additional markers were designed to determine flanking regions: bx321GF, CAAAACCCTACTGACCC; bx321GR, GGAATTTTCCTTTATGGACA; bx537NF, GCGTTCTGAAGTCTCCTCT; bx537NR, GTGATGGTGCCACTAAATGA.

Heat-shock conditions and morpholino injection

The Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP)-positive embryos were heat-shocked at 28 hpf for 30 minutes at 39°C using a Thermo Cycler (BioRad). Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP)-positive embryos were identified by GFP expression.

Antisense oligonucleotide morpholinos (MO) were microinjected into fertilized zygotes at the concentrations indicated. The lef1-MO, which blocks the splice donor site at exon 8/intron 8 (a gift from the Dorsky lab, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; TTTTAAGATACGAACCCTCCGGCC) (Rai et al., 2010), was injected at 4 ng/nl. The tcf7-MO (a gift from the Dorsky lab) (Bonner et al., 2008) was injected at 2 ng/nl along with 3 ng/nl p53-MO (Robu et al., 2007).

In situ hybridization, immunolabeling, BrdU incorporation and image processing

RNA in situ hybridization was performed as described previously (Andermann et al., 2002). Digoxygenin- or fluorescein-labeled antisense RNA probes were generated for the following genes: eya1 (Sahly et al., 1999), fgf10a (Grandel et al., 2000), pea3 (Raible and Brand, 2001; Roehl and Nusslein-Volhard, 2001), lef1 (Dorsky et al., 1999), tcf7 (Veien et al., 2005), tcf7l1a (Dorsky et al., 2003), tcf71b (Dorsky et al., 2003) dkk1 (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008), cxcr4b and cxcr7b (Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 2007). Whole-mount immunolabeling was performed following established protocols (Ungos et al., 2003). The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000; Invitrogen), rat or mouse anti-BrdU (1:100; Abcam or 1:20; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank); mouse anti-GFP (1:1000; Invitrogen), rabbit anti-Lef1 (1:200) (Lee et al., 2006), Alexa-488 (1:1000) and Alexa-568 (1:1000). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI. BrdU incorporation was carried out between 32.5 and 34.0 hpf using the protocol described by Laguerre et al. (Laguerre et al., 2005) followed by a published BrdU detection protocol (Harris et al., 2003; Laguerre et al., 2005). Fluorescently labeled embryos were imaged using Olympus FV1000 confocal system. Bright-field or Nomarski microscopy images were collected using Zeiss Lumar and Imager Z1 systems. Images were processed using ImageJ software (Abramoff et al., 2004). Brightness and contrast were adjusted in Adobe Photoshop.

Western blotting

For western blot analysis, protein was isolated from Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP), lef1nl2 and lef1-MO embryos. For each condition, 16 dechorionated (2 dpf) embryos were homogenized in sample buffer (55 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaHCO3) with proteinase inhibitors, run on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and blotted onto a PVDF membrane. Anti-Lef1 antibody was used at 1:2000 (Lee et al., 2006). Anti-rabbit conjugated-HPR antibody (Invitrogen) was applied at 1:10,000 and visualized using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate according to the manufacturer's specification (Thermo Scientific). The blot was stripped with 25 mM glycine (pH=2.5) and 1% SDS and re-probed with rabbit anti-α-actin (1:10,000; Sigma) using the same secondary antibody.

Transplantation experiments

Transplantation experiments were carried out as previously described (Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). All host embryos expressed the Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP) and/or TgBAC(neurod:EGFP) transgenes. Donor zygotes were injected with fixable rhodamine dextran (Invitrogen). All host embryos receive donor cells in the left side, whereas the right side served as control. lef1nl2 donors were derived from heterozygous crosses of lef1nl2/+ adults. Donors were individually assessed for the mutant phenotype at 3 dpf and correlated to their respective host embryos. Cells from heterozygous Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) donors were transplanted into wild-type hosts. Hosts were collected with their respective donors and heat-shocked as described above at 28 hpf.

Time-lapse imaging and Kaede photoconversion

For time-lapse imaging, embryos were anesthetized in 0.02% tricaine (MS-222; Sigma), embedded in 1.2% low-melting point agarose and imaged using a 20×/NA=0.95 dipping lens on an FV1000 (Olympus) confocal system for 12-14 hours with z-stacks collected at 6-minute intervals. Images were processed using ImageJ software. The progeny from lef1nl2 heterozygous incrosses that also contained the Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP) and the TgBAC(neurod:EGFP) transgenes were injected at the one-cell stage with 200 pg of NLS-Kaede mRNA (Ando et al., 2002). The Kaede fluorophore was photo-converted between 22 and 24 hpf in one to four cells using 405 nm laser and 60×/NA=1.2 lens. Subsets of embryos were subjected to time-lapse imaging as described above. The remaining embryos were assessed for the number and location of red cells at 48 hpf.

TUNEL labeling

TUNEL labeling was carried out according to an established protocol modified for fluorescent detection (Nechiporuk et al., 2005). For global Wnt inactivation, Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) embryos were heat-shocked at 28 hpf and fixed in 4% PFA at 34 hpf. lef1nl2 mutant and wild-type sibling embryos were fixed at 40 hpf.

Statistics

A two-sample Student's t-test assuming equal variance was used to compare total NM counts, BrdU incorporation indexes and pH3 labeling. Two-way ANOVA with replication was used to compare axial level of NMs in the different treatment conditions. Student's t-test and ANOVA were run using Excel software. To analyze lef1nl2 mutant to wild-type transplants, we employed Fisher's Exact Test (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/fisher.html).

Dermal bone and cartilage staining

Adult lef1nl2 mutants and wild-type siblings of comparable size were collected at 3 months post-fertilization. Alizarin Red staining was used to label bone and Alcian Blue staining was used to label cartilage according to established protocols (Elizondo et al., 2005).

RESULTS

Loss of rosette renewal leads to the truncation of the pLL in the lef1nl2 mutant

The lef1nl2 mutation was isolated in an ongoing ENU-based mutagenesis screen designed to identify recessive mutations with defects in pLL formation. The lef1nl2 mutation was isolated based on a lack of caudal-most NMs as visualized by DASPEI, a vital dye that labels hair cells (see Fig. S1A,B in the supplementary material). Deposited NMs in the lef1nl2 mutant contained similar numbers of hair and support cells when compared with wild-type siblings (see Fig. S1E,F in the supplementary material). Expression of the lateral line marker eya1 revealed that in lef1nl2 mutants, the first 5 pLL NMs were deposited along the trunk, though at a more anterior axial level than wild-type NMs (Fig. 1A-D). However, the terminal cluster (tc) of NMs at the end of the tail was invariably absent in lef1nl2 mutants and only a small trail of cells extended distally from the last deposited NM (Fig. 1A′,B′). Because the loss of NMs often results from pLL primordium abnormalities, we examined primordium organization during migration through time-lapse imaging in lef1nl2 mutants and wild-type siblings expressing the Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP) transgene between 34 and 48 hpf (Fig. 1E,F). In a wild-type embryo, the migrating primordium deposited three trunk NMs and the tc at the end of the trunk (Fig. 1E-E′′; see Movie 1 in the supplementary material). NM deposition was closely coupled to rosette renewal; a new rosette formed shortly after the deposition of each NM (Fig. 1E′,E′′). In a lef1nl2 mutant embryo, the pLL primordium contained three or four rosettes between 34 and 48 hpf and deposited the 4th and 5th NMs. The primordium became progressively smaller and failed to form new rosettes as the NMs were dropped off, leaving only a narrow trail of cells that migrated a short distance distal to the last NM (Fig. 1F′-F′′′; see Movie 2 in the supplementary material). We conclude that lef1nl2 is not required for the trunk NM deposition, but rather is required for formation of the tc, possibly by regulating rosette renewal during later stages of pLL formation.

Fig. 1.

Abnormal primordium patterning leads to loss of terminal neuromasts in the lef1nl2 mutant. (A,B) eya1 expression in the pLL of wild-type sibling and lef1nl2 mutant embryos at 2 dpf. The lef1nl2 mutant lacks a tc. (A′,B′) Distal limit of eya1 expression in wild-type and lef1nl2 mutant (arrow) embryos. (C) Average number of NMs (excluding tc) in lef1nl2 mutant and wild-type sibs (mean±s.d.) are not significantly different at 2 dpf (n=28 wild type, 11 lef1nl2, P=0.49, Student's t-test). (D) Axial positions of L1-L5 in lef1nl2 and wild-type siblings at 2 dpf (mean±s.d.). The axial level of stalled primordium (prim) in lef1nl2 mutants is indicated by the pink bar. Position of L1-L5 is significantly shifted anteriorly in lef1nl2 mutants (n=18, P<0.001, two-way ANOVA with replication). (E-F′′) Stills from time-lapse movies of primordium migration in wild-type sibling and lef1nl2 mutant embryos that express the Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP) transgene. Wild-type and lef1nl2 embryos were imaged beginning at 34 hpf for 780 minutes and 840 minutes, respectively (see Movies 1 and 2 in the supplementary material). (E-E′′) Over the course of 780 minutes, the primordium in the wild-type embryo migrated out of frame, deposited three NMs (red, blue and yellow asterisks) and generated two new rosettes (green and pink asterisks). (F-F′′′) Over the course of 840 minutes, the primordium in the lef1nl2 mutant has slowed and became elongated (pink asterisk), having deposited four NMs (red, blue, yellow and green asterisks). Scale bars: 20 μm.

Adult lef1nl2 mutants exhibit defects in dermal bone development and lateral line maturation

Homozygous lef1nl2 mutants develop into viable adults, although they were often malformed (see Fig. S2A,B in the supplementary material). Alizarin Red staining of calcified bone revealed that lef1nl2 mutant adults had stunted lepidotrichia, leading to severely malformed pectoral, pelvic and caudal fins; dorsal and anal fins were less affected (see Fig. S2C,D′ in the supplementary material). lef1nl2 mutants also showed a dramatic loss of teeth and short gill rakers (see Fig. S2E,F in the supplementary material and data not shown); other jaw structures appeared normal.

The lef1nl2 mutant adults also showed defects in late pLL development. During the metamorphosis from larva to adult, the pLL undergoes a dramatic expansion in the number and location of NMs, that relies entirely on precursor cells deposited during the formation of the embryonic pLL (Nunez et al., 2009). In lef1nl2 mutants, the pLL was able to assume the adult morphology of lines of NMs, called stitches, that are arranged dorsoventrally along the trunk (see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material). In contrast to wild types, several posterior stitches were absent in lef1nl2 mutants, probably owing to the failure of pLL extension during embryonic development. We conclude that Lef1 is required for the proper development of several organs in the adult.

The lef1nl2 mutation disrupts the lef1 gene

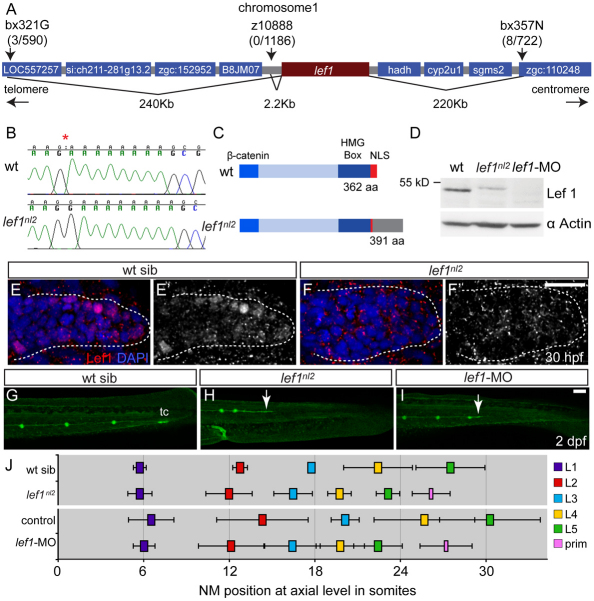

We used positional cloning to identify the genetic lesion in lef1nl2. Initial meiotic mapping of 405 lef1nl2 embryos and 188 wild-type siblings on an *AB/WIK background placed the mutation between z43517b and z21408 on the distal arm of chromosome 1. Further analyses narrowed the region that flanked the lef1nl2 mutation to ∼460 kb (Fig. 2A). Within this region, the microsatellite marker z10888 showed tight linkage to the lef1nl2 mutation (0/1186 meioses). The start of the protein-coding region for lymphocyte enhancer binding factor 1 (lef1) lies 2.2 kb centromeric to z10888. We found that lef1nl2 mutants contained a guanine insertion at base pair 1120 (Fig. 2B) in the lef1 gene. This insertion led to a frame shift that produced a new stop site 29 amino acids downstream from the endogenous stop (Fig. 2C). Western blot analysis using an antibody raised against zebrafish Lef1 confirmed that in lef1nl2 mutants, the Lef1 protein had a higher molecular weight than wild type (Fig. 2D). The mutant protein appears to be less stable, as we detected 60% less protein in the mutant when compared with wild-type extracts. Immunolabeling with the anti-Lef1 antibody revealed that, in wild-type siblings, Lef1 protein localized predominantly to nuclei in the leading portion of the primordium (Fig. 2E,E′). By contrast, in lef1nl2 mutants, Lef1 protein was localized to the cytoplasm and excluded from the nuclei (Fig. 2F,F′), suggesting that the mutant protein is not transcriptionally functional.

Fig. 2.

The lef1nl2 mutant contains a lesion in the lef1 gene. (A) The lef1nl2 mutation was mapped to a 460 Kb region on chromosome 1. Numbers of recombinants are indicated under each marker. (B) The lef1nl2 mutation is a single guanine insertion at position 1120 (red asterisk). (C) The resulting frame shift is predicted to disrupt the nuclear localization signal (NLS) and extend the protein by 29 amino acids (aa; also shown a β-catenin binding domain and HMG Box). (D) Western blot of wild-type, lef1nl2 mutant and lef1 morphant whole embryo lysates probed with anti-Lef1 antibody and anti-α actin antibody. (E-F′) Immunolabeling using anti-Lef1 antibody revealed nuclear labeling (red) in wild-type sibling and cytoplasmic labeling in lef1nl2 mutant embryos. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI. (G-I) Wild-type sibling, lef1nl2 mutant and lef1-MO injected embryos expressing the Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP) transgene at 2 dpf. (G) The pLL was truncated prematurely (white arrows) in the lef1nl2 mutant (H) and lef1 morphant (I). (J) The axial positions of the deposited NMs are shifted anteriorally in lef1nl2 mutants when compared with wild-type siblings and in lef1 morphants when compared with uninjected controls. (Data presented as mean±s.d.; n=6-11 P<0.001, two-way ANOVA with replication.) Scale bars: 50 μm.

To confirm that disruption of the lef1 gene was indeed the cause of the lef1nl2 mutant phenotype, we used an antisense morpholino oligonucleotide to block lef1 splicing (lef1-MO) (Ishitani et al., 2005). Western blot analyses revealed that Lef1 protein was completely lost in lef1 morphants (Fig. 2D). Injection of lef1-MO produced embryos that had a pLL phenotype nearly identical to that of the lef1nl2 mutant (Fig. 2G-J). All together, these results demonstrate that the lef1nl2 mutation causes a complete or nearly complete loss of Lef1 function.

Patterning of the pLL primordium is maintained in lef1nl2 mutants

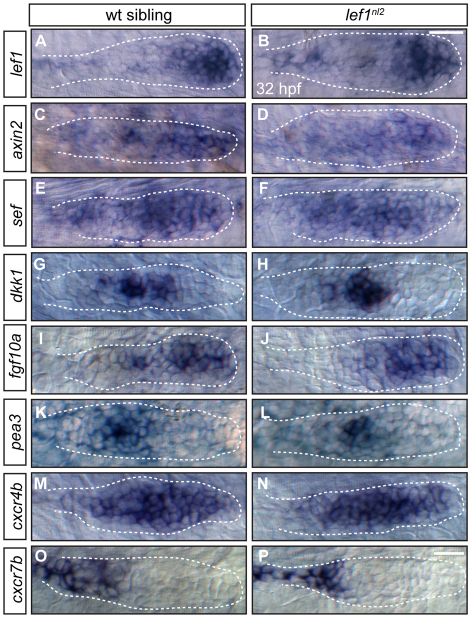

To determine whether patterning of the pLL primordium is disrupted in lef1nl2 mutants, we examined expression of gene markers at 32 hpf. Both the expression and localization of axin2, sef, dkk1, fgf10a and pea3 appeared grossly normal in lef1nl2 mutants when compared with wild-type siblings (Fig. 3C-L). lef1 transcript is detectable in lef1nl2 mutants, indicating that the mutation does not cause mRNA decay (Fig. 3A,B). By contrast, the expression of these factors was lost following global inactivation of Wnt signaling using the Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) transgene (see Fig. S4A-F in the supplementary material), as previously reported (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008).

Fig. 3.

Primordium patterning is maintained in lef1nl2 mutants. (A-P) RNA in situ hybridization of factors required for primordium patterning in wild-type siblings (left panels) and lef1nl2 mutants (right panels) at 32 hpf. Expression of lef1 (A,B), axin2 (C,D), sef (E,F), dkk1 (G,H), fgf10a (I,J), pea3 (K,L), cxcr4b (M,N) and cxcr7b (O,P) are similar in both wild-type and mutant embryos. Scale bars: 20 μm.

The chemokine receptors cxcr4b and cxcr7b are differentially expressed in the pLL primordium and are required for its migration (Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 2007; Valentin et al., 2007). Global inactivation of Wnt signaling by expression of Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) has been previously reported to expand the zone of cxcr7b without altering cxcr4b expression (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). By contrast, when we compared the expression patterns of cxcr4b and cxcr7b in wild-type siblings with those in lef1nl2 mutants (Fig. 3M-P) or Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) embryos, we did not observe any significant differences (see Fig. S4G-J in the supplementary material). Overall, these data indicate that loss of Lef1 activity does not affect primordium patterning.

Loss of Lef1 and Tcf7 does not replicate the pLL defects observed with the complete loss of Wnt signaling

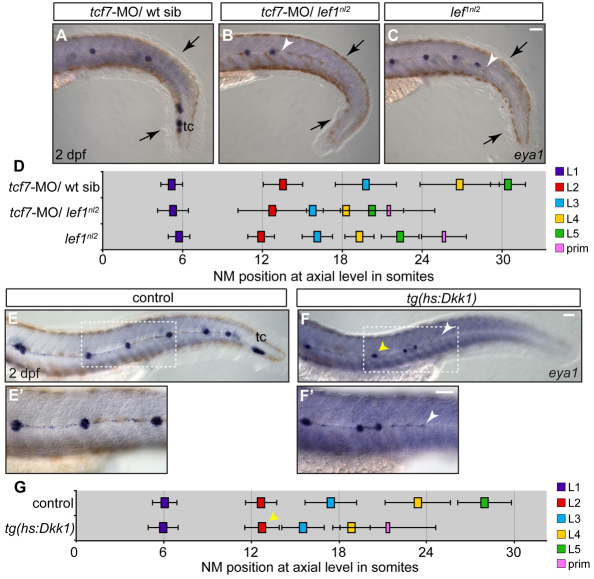

In systems such as the mouse limb, the Wnt effector Tcf7 exhibits redundant functions with Lef1 during development (Galceran et al., 1999). tcf7 was expressed in the leading region of the primordium (see Fig. S5A in the supplementary material). By contrast, transcripts of two other Wnt effector genes, tcf7l1a and tcf7l1b, were excluded from the leading zone of the primordium (see Fig. S5B,C in the supplementary material). We injected a tcf7 morpholino (tcf7-MO) into zygotes derived from a lef1nl2 heterozygous intercross to determine whether combined loss of Tcf7 and Lef1 affects pLL formation. When Tcf7 function was blocked in wild-type siblings, the pLL developed normally, as reported previously (Aman et al., 2010) (Fig. 4A). tcf7-MO/lef1nl2 embryos were identified by loss of the pectoral fin fold (see Fig. S5D,E in the supplementary material) (Nagayoshi et al., 2008) and showed a loss of terminal cluster NMs similar to that of lef1nl2 mutants (Fig. 4B,C). Both the axial level of the deposited NMs and the axial level at which the pLL was truncated were shifted anteriorly when compared with uninjected lef1nl2 mutants (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, whereas NM number is not perturbed in lef1nl2 mutants or tcf7 morphants, tcf7-MO/lef1nl2 embryos had fewer NMs (see Fig. S6A in the supplementary material). Thus, Tcf7 and Lef1 show a level of functional redundancy during development of the pLL.

Fig. 4.

Combined loss of Lef1 and Tcf7 does not recapitulate the pLL phenotype seen with the complete loss of Wnt signaling. (A-C) Zygotes from a lef1nl2/+ incrosses were injected with tcf7-MO. NM distribution in the injected embryos was assessed by eya1 expression at 2 dpf and compared with uninjected lef1 mutant embryos. The loss of Tcf7 alone did not affect pLL patterning in lef1nl2/+ sibling (A), the pLL is truncated more severely lef1nl2/–; tcf7-MO (B; arrowhead) compared with lef1nl2 mutants alone (C; arrowhead). Note reduced fin fold (black arrows) caused by a combined loss of Lef1 and Tcf7 as reported previously (Nagayoshi et al., 2008). (D) Axial positions of the pLL NMs (L1-L5) and primordium (mean±s.d.; n=11, P<0.001, two-way ANOVA with replication). (E-F′) pLL formation in 2 dpf embryos following the induction of Dkk1 in the Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) line by a heat-shock at 28 hpf. Position of the primordium at the time of heat-shock is marked by the yellow arrowheads. Dashed rectangles indicate the regions shown at higher magnification in E′,F′. Following the heat-shock, one or two NMs are deposited and the pLL ends with a trail of eya1-positive cells (white arrowheads). (G) Axial positions of NMs deposited following heat-shock in control and Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) embryos (n=11). Scale bars: 20 μm.

The pLL defects caused by the combined loss of Lef1 and Tcf7 function, however, were not as severe as those caused by global inhibition of Wnt signaling. Following induction of Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) at 28 hpf, the primordium deposited only 1 or 2 NMs prior to disorganization and extension in a thin trail of cells that arrest midway along the trunk (Fig. 4E-F). There was a reduction in the number of additional NMs deposited following activation of the transgene (see Fig. S6B in the supplementary material). Taken together, these data show that Tcf7 is an effector of the canonical Wnt pathway in the pLL primordium in addition to Lef1, though global inhibition of Wnt signaling leads to more severe abnormalities in the pLL, suggesting the existence of other effectors.

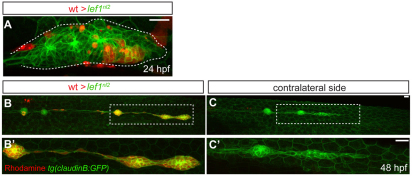

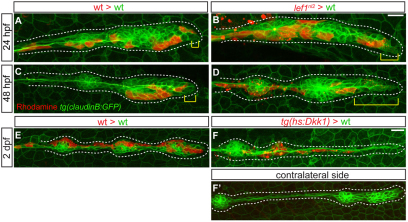

Lef1 is required in leading zone cells for primordium migration and terminal cluster formation

The expression pattern of lef1 in the leading zone of the primordium and the rosette renewal defects in the lef1nl2 mutant both suggest that Lef1 may be specifically required in cells within the leading zone. Using gastrula-stage transplants, we obtained 15 mosaic embryos in which rhodamine-labeled wild-type donor cells were localized to the leading region of the primordium by 48 hpf. In 14 of 15 cases, mosaic primordia that contained donor cells in the leading region at 48 hpf migrated to the end of the tail and formed the tc (Fig. 5B,B′). Primordia on the contralateral control sides of these embryos, which did not receive wild-type cells, did not show complete migration or form the tc (Fig. 5C,C′). A small subset of these embryos (n=4) was followed using time-lapse imaging to trace the location of the donor cells between 24 and 48 hpf. In these embryos, donor cells resided within the caudal-most rosette and the leading zone (Fig. 5A); this distribution of donor cells was sufficient to rescue the formation of the tc in 3 out 4 embryos (Fig. 5 and data not shown). In all chimeric embryos, the tc consisted predominantly of the donor cells (Fig. 5B and data not shown), supporting the idea that Lef1 activity is required in the leading, proliferative progenitor cells for primordium migration and tc formation.

Fig. 5.

Lef1 function is required in leading edge cells of the primordium for proper pLL formation. (A-C′) Confocal projection obtained from a lef1nl2 mutant host that received wild-type donor cells (rhodamine dextran, red). (A) At 24 hpf, the primordium contains donor cells in the leading zone and caudal-most rosette. (B) The same embryo as in A, showing complete primordium migration and tc formation at 48 hpf. (B′) High magnification of region outlined in B; the primordium is entirely composed of donor cells. (C) Lateral line is truncated on the contralateral side of the same embryo. (C′) High magnification of the region outlined in C. Both wild-type donors and mutant hosts expressed Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP) transgene. Scale bars: 20 μm.

Loss of Lef1 function leads to reduced cell proliferation in the leading edge of the primordium

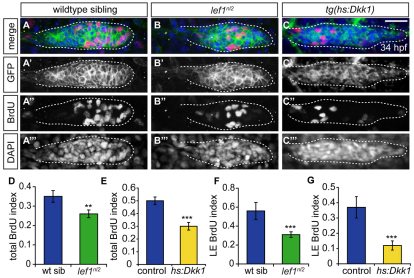

As the overall patterning of the pLL primordium was not affected in lef1nl2 mutants, we reasoned that Lef1 might regulate a process necessary for rosette formation or renewal such as proliferation. In the migrating primordium, proliferation levels are high in the leading zone cells (Aman et al., 2010; Laguerre et al., 2009; Laguerre et al., 2005). This is consistent with the finding that a small population of cells in the leading edge acts as proto-NM progenitors (Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). To analyze proliferation levels in lef1nl2 mutants and wild-type siblings, we used BrdU incorporation to mark cells in S phase. We found a significant reduction in the percentage of cells that incorporated BrdU in the primordia of mutants versus their wild-type siblings (26% reduction, Fig. 6A,B,D). The decrease in proliferative cells appeared to be confined to the leading region of lef1nl2 mutant primordia (Fig. 6A′,B′). To confirm this finding, we examined the BrdU incorporation index in leading edge cells. The leading edge was defined as cells caudal to most recently formed rosette. lef1nl2 mutants showed a significant reduction in the index of BrdU-positive cells in this region versus wild-type controls (45% reduction, Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

Wnt signaling regulates proliferation in the primordium. (A-C′′) Confocal projections of primordia following BrdU incorporation between 32.5 and 34.0 hpf in wild-type, lef1nl2 mutant and Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) embryos. All embryos express Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP). BrdU incorporation in the primordia of the wild-type (A-A′′), the lef1nl2 mutant (B-B′′) and the Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) transgenic embryos heat-shocked at 28 hpf (C-C′′). Scale bar: 20 μm. (D,E) BrdU incorporation index for wild-type sibling and lef1nl2 mutants (D) and control and Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) embryos (E). (F,G) BrdU incorporation index for leading region in wild-type siblings and lef1nl2 mutants (F) and controls and Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) embryos (G) (n=10-22 embryos; data presented as mean±s.e.m., **P<0.009, ***P<0.002, Student's t-test). The leading region is defined as the cells posterior to the leading rosette in the primordium.

As inhibition of Wnt signaling by Dkk1 induction leads to a reduction in proliferation in the primordium (Aman et al., 2010), we asked how this reduction compared with that seen in lef1nl2 mutant primordia. Upon induction of Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) at 28 hpf, we saw a loss of BrdU-positive cells throughout the primordium (40% reduction, Fig. 6C,E) and a dramatic reduction of BrdU-positive cells in the leading region (68% reduction, Fig. 6G). These data indicate that in addition to the leading zone, Wnt activity regulates proliferation throughout the trailing region of the primordium.

To determine whether the decrease of proliferation in the primordia of lef1nl2 mutants and Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) embryos were due to increased in cell death, we performed TUNEL assays. There were few-to-no TUNEL-positive cells in the primordia of wild-type, lef1nl2 mutant or lef1-MO injected embryos (see Fig. S7A-D in the supplementary material). There was a low level of TUNEL-positive cells in the primordia of Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) embryos that were heat-shocked at 28 hpf (see Fig. S8A,B in the supplementary material). These data indicate that Wnt signaling is required for cell proliferation and/or survival in the pLL primordium. However, these cellular effects are at least partially mediated by factors other than Lef1.

Leading edge cells in lef1nl2 mutants are preferentially sorted out of the primordium.

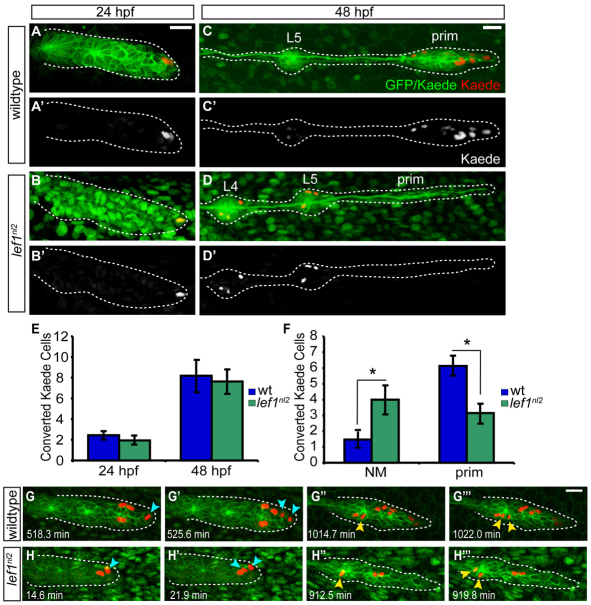

Our mosaic analyses indicated that Lef1 activity is required in the leading region of the primordium, but is not solely responsible for regulating cellular proliferation. Thus, we reasoned that Lef1 might be necessary for identity of the primordium progenitor cells. Previous studies have indicated that progenitors reside in the leading edge of the primordium (Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008), probably immediately rostral to the leading tip cells. We used Kaede photoconversion to follow the fate of these leading cells in wild-type controls and lef1nl2 mutants. An average of two cells were photoconverted at 24 hpf; at this stage the primordium already contained three or four proto-NMs (Fig. 7A,B,E). The progeny of the labeled cells were assayed at 48 hpf (Fig. 7C-F). In wild-type embryos, converted cells primarily remained in the primordium, which formed the tc at 48 hpf (Fig. 7C,F). The positions of the red Kaede cells were significantly different in lef1nl2 mutants; we found fewer labeled cells in the primordium and more cells incorporated into deposited NMs versus controls (Fig. 7C,D,F). There was no significant difference in the number of red Kaede cells at 48 hpf between wild-type embryos and lef1nl2 mutants (Fig. 7E), indicating that the labeled cells in both groups divided an equal number of times. These results suggest that Wnt signaling through Lef1 is necessary to retain progenitor cells in the leading region of the primordium.

Fig. 7.

Leading region cells change their fate in the absence of Lef1 function. (A-C′) Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP) zygotes were injected with a nuclear-localized Kaede mRNA and an average of two cells were photoconverted at 24 hpf. (A,B) Wild-type and lef1nl2 mutant embryos immediately following photoconversion are shown. (C-D′) The embryos in A-B′ at 48 hpf showing the location of the progeny of the photoconverted cells. Note absence of the labeled (red) cells in the leading region of lef1nl2 mutant embryos. (E) Quantification of converted cells at 24 hpf and their progeny at 48 hpf. (F) Localization of converted cells at 48 hpf in wild-type and lef1nl2 mutants. Cells in lef1nl2 mutants are significantly more likely to be localized in NMs and not in the primordia when compared with wild type (mean±s.e.m., n=27 wild-type and 16 lef1nl2 mutant embryos, *P<0.04, Student's t-test). (G-H′′) Still images from time-lapse movies (see Movies 3 and 4 in the supplementary material) demonstrating division of Kaede-positive cells (red) in a wild-type (G-G′′) and a lef1nl2 embryos (H-H′′). Specific time points were chosen to show a subset of labeled cells just before and after cell divisions. Leading zone divisions marked by blue arrows, whereas cell divisions in rosettes are marked by yellow arrowheads. Scale bars: 20 μm.

Together, our BrdU incorporation and lineage-tracing experiments indicate that the loss of Lef1 activity may affect a pattern of proliferation rather than an actual rate of cell division within the leading region. To address this question, we studied the cell division of converted Kaede cells in wild-type and lef1nl2 mutant embryos using live imaging (n=4; see Fig. S9 in the supplementary material). In wild-type embryos, the majority of cells divided in the leading zone of the primordium (12/15 cell divisions), although a small subset divided in rosettes (3/15 cell divisions; Fig. 7G-G′′; see Movie 3 in the supplementary material). By contrast, in the lef1nl2 mutants, we observed dividing cells in the rosettes (4/9 cell divisions) and deposited NMs (2/9 cell divisions) as well as in the leading zone (3/9 of cell divisions; Fig. 7H-H′′; see Movie 4 in the supplementary material). These experiments suggest that, although leading cells are able to proliferate in lef1nl2 mutants, they fail to remain in the leading zone and are preferentially incorporated into NMs. We suggest that this abnormal pattern of cell division is responsible for the reduction in BrdU incorporation levels observed in the lef1nl2 mutant primordia.

To explore further the role Lef1 plays in conferring progenitor identity, we compared the behavior of lef1nl2 mutant and wild-type cells transplanted into wild-type hosts. In chimeric embryos containing wild-type donor cells in their primordia, eight out of 28 (28.6%) had donor cells localized to the leading region at 48 hpf. By contrast, we never found cells derived from a lef1nl2 donor localized to the leading edge of wild-type primordia (n=24; P<0.02, Fisher's Exact Test). In a subset of these embryos, we examined mosaic primordia during the course of migration. At 24 hpf, donor cells from either wild-type or mutant donors were located in the leading zone of host primordia (n=4; Fig. 8A,B). At 48 hpf, wild-type donor cells remain in the leading region, whereas lef1nl2 mutant donor cells have left the leading region (Fig. 8C,D; see Movies 5, 6 in the supplementary material). Together with the lineage data, these results suggest that Lef1 is required to regulate progenitor identity and localization in the leading zone of the primordium.

Fig. 8.

Lef1 is required to maintain progenitor cell identity. (A-D) Confocal projections of Tg(–8.0cldnb:lynGFP)-positive, mosaic embryos containing either wild-type or lef1nl2 donor cells (red) at 24 and 48 hpf. (A) Wild-type host primordium at 24 hpf with wild-type donor cells in the leading region (yellow bracket). (B) Chimeric primordium containing lef1nl2 mutant cells in the leading region at 24 hpf (yellow bracket). At 48 hpf, wild-type donor cells remain in the leading region (C; yellow bracket), whereas lef1nl2 cells have moved out of the leading region (D; yellow bracket). (E-F′) Confocal projections of chimeric primordia containing wild type Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) donor cells. Embryos were heat-shocked at 28 hpf. (E) Primordium containing wild-type cells and a characteristic rounded morphology. (F) Wild-type primordium containing Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) donor cells shows loss of primordium organization. (F′) Contralateral side of the chimera shown in F is normal. Scale bars: 20 μm.

We next asked whether a complete lack of Wnt activity altered donor cell behavior. We transplanted wild-type or Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) donor cells into wild-type hosts and heat-shocked the resulting chimeras at 28 hpf. Wild-type cells were incorporated into the primordium and migrated normally (Fig. 8E; see Movie 5 in the supplementary material). In contrast to the lef1nl2 donor cells, the Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP)-positive cells remained in the leading edge and altered the behavior of the chimeric primordium (n=4, Fig. 8F,F′; see Movie 7 in the supplementary material). Shortly after the heat-shock, chimeric primordia lost organization and elongated. This result suggests that cells in which the diffusible factor Dkk1 has been ectopically expressed are able to exert non-autonomous effects on neighboring wild-type cells.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we describe a novel zebrafish strain (lef1nl2), which contains a mutation in lef1, a downstream effector of canonical Wnt signaling. In contrast to a global loss of Wnt signaling, which severely disrupts patterning, proliferation and organization throughout the primordium, loss of Lef1 activity resulted in a distinct, late defect in rosette renewal. Fate mapping and mosaic analyses support the idea that this failure results from a loss of leading region progenitor cells and not reduced proliferation, defining a previously unrecognized role for Wnt signaling in pLL primordium organization.

Pattern of rosette renewal in the pLL primordium

One distinct feature of the lef1nl2 phenotype is the relatively normal deposition of the rostral NMs. Consistent with our observations, a recent study using morpholinos to block lef1 function found that NMs L1-L4 were deposited normally (Gamba et al., 2010). This suggests that Lef1 activity, which is necessary for proper specification and/or maintenance of the progenitor population, is not required during the initial patterning of proto-NMs. In both the lef1nl2 mutant and wild-type embryos, NMs L1-L4 correspond to first four proto-NMs that are initially specified within the primordium, whereas the L5 NM and terminal neuromasts arise from cells posterior to the last proto-NM. In the absence of Lef1 activity, cells leave the leading zone and prematurely incorporate into NMs, leaving an insufficient number of cells to generate new rosettes after the initial proto-NMs are deposited. We suspect that migration of the remaining cells continues only as long as the cohort remains in contact.

Multiple nuclear effectors mediate Wnt activity in the primordium

Our studies revealed that Lef1 mediates a novel Wnt-dependent role in primordium organization distinct from previously described Wnt functions such as patterning, proliferation and NM deposition (Aman et al., 2010; Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). We found that although global inhibition of the Wnt pathway disrupted expression of several factors, including fgf10a, pea3, lef1 and dkk1 (although not cxcr7b as previously reported), expression patterns of these factors were grossly normal in the primordia of lef1nl2 mutants. These results suggest that Lef1 is not required for primordium patterning.

A second major difference between global Wnt inhibition and loss of Lef1 activity alone is in the respective numbers of NMs deposited. Embryos in which Wnt activity was blocked during early stages of primordium migration deposited only one or two additional NMs, and migration stalled at the level of the posterior trunk. Moreover, analyses of the chimeric embryos demonstrated that in contrast to the lefnl2 mutant cells, Dkk1-expressing cells were able to alter the behavior of their surrounding wild-type neighbors to produce a phenotype similar to that seen in our global Wnt inhibition experiments. Our observations of early primordium stalling following Wnt inhibition and a lack of expansion in cxcr7b expression differ from what had been observed previously. Aman and Piotrowski reported that primordium migration continued along the length of the trunk and that cxcr7b expanded throughout the primordium following activation of the Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) transgene (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). It is possible that we used more stringent heat-shock conditions, as we also observed cell death with a concurrent loss in proliferation following activation of the Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) transgene, which had not been reported previously. Our observations indicate discrete roles for Wnt activity in cell proliferation and survival within the primordium. We hypothesize that this significant loss of cells results in early disruption of primordium organization and subsequent arrest in primordium migration.

These differences between global Wnt pathway inactivation and loss of Lef1 activity alone may reflect the requirement of multiple Lef1/Tcf factors to mediate canonical Wnt activity. For example, in mouse, loss of both Lef1 and Tcf7 were required to recapitulate the phenotype seen in the Wnt3a knockout (Galceran et al., 1999). Indeed, we observed a more severe truncation of the pLL when we blocked Tcf7 function in lef1nl2 mutant embryos. Although, this phenotype was still not as severe as the one that resulted from global Wnt inhibition, suggesting that additional Tcf factors may regulate primordium patterning and NM deposition. Alternatively, some of the phenotypes that result from activation of the Tg(hsp70l:dkk1-GFP) transgene may be due to disruption of a non-canonical Wnt pathway, as induction of Dkk1 can also inhibit non-canonical Wnt signaling (Cha et al., 2008). Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that the leading progenitor cells are especially sensitive to decreased levels of Wnt activity in the absence of Lef1. Future work is needed to distinguish between these multiple possibilities of how Wnt signaling regulates identity of the leading progenitor cells.

Lef1 is required for progenitor cell identity in the primordium

Previous work has shown that a small number of cells in the leading edge of the primordium act as a progenitor population to produce new proto-NMs (Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008), though the molecular and cellular mechanisms that regulate specification and renewal in primordium progenitor cells had not been established. It is also not clear whether this population is established before or after the onset of primordium migration (∼22 hpf). Previous fate mapping demonstrated that the progenitors were already present at 24 hpf (shortly before the L1 is deposited) and gave rise to the progeny that populated the caudal NMs and the terminal cluster in the pLL (Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). In the present study, we took advantage of this observation to investigate the fate of the progenitor cells in the lef1nl2 mutant by lineage analyses. In the absence of Lef1 activity, labeled cells left the primordium and were incorporated into the caudal NMs in greater numbers when compared with wild-type embryos. This suggests that Lef1 activity is required for the presence of progenitor cells within the leading edge of the primordium. This was further confirmed by mosaic analyses, which revealed that lef1nl2 mutant cells were excluded from the leading edge when placed in a wild-type environment. This is consistent with our observation that the cells in lef1nl2 mutants tend to undergo cell division after exiting the leading zone, whereas the vast majority of wild-type cells divide in the leading zone of the primordium. This abnormal pattern of cell divisions explains the apparent contrast between the loss of BrdU incorporation in the leading zone of lef1nl2 mutant primordia and the fact that lineage labeled cells in lef1nl2 mutants undergo the same number of cell division as those seen in wild-type embryos.

An unresolved issue about Lef1 is whether its function is required to specify progenitor cells or to maintain progenitor cell identity. There are a number of studies demonstrating that canonical Wnt signaling is involved in progenitor specification in multiple organ systems such as heart, hematopoietic and nervous systems (Freese et al., 2010; Gessert and Kuhl, 2010; Grigoryan et al., 2008; Staal and Luis, 2010). In addition, Wnt signaling has been implicated in maintaining progenitor cell self-renewal as well as in maintaining progenitor identity (Grigoryan et al., 2008; Nusse, 2008). Alternatively, Lef1 activity may regulate cell-cell adhesion in the primordium. However, levels of cadherin 2, which is prominently expressed in the leading region (Kerstetter et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2003; Matsuda and Chitnis, 2010), were not altered in lef1nl2 mutant primordia (data not shown). Distinguishing between these possible roles for Wnt/Lef1 signaling in the lateral line system will require generation of specific markers that identify the progenitor cells during various stages of development to define the dynamics of their behavior in wild-type and lef1nl2 mutants.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a previously unreported role for Wnt signaling through Lef1 in regulating progenitor cells in the zebrafish pLL primordium. We also suggest that Wnt signaling requires multiple downstream effectors to mediate its functions during primordium migration and pLL formation. These results provide a model in which a signaling pathway can regulate multiple aspects of collective cell migration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Piotrowski and Dorsky laboratories for reagents, and Jan Christian for her comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Basic Research Training in Embryonic Development NIH grant 5T32HD049309-05 to H.F.M. and by funds from March of Dimes (5-FY09-116), NICHD (HD0550303) and Medical Research Foundation of Oregon to A.V.N. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.062554/-/DC1

References

- Abramoff M. D., Magelhaes P. J., Ram S. J. (2004). Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 11, 36-42 [Google Scholar]

- Aman A., Piotrowski T. (2008). Wnt/beta-catenin and Fgf signaling control collective cell migration by restricting chemokine receptor expression. Dev. Cell 15, 749-761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A., Piotrowski T. (2009). Multiple signaling interactions coordinate collective cell migration of the posterior lateral line primordium. Cell Adh. Migr. 3, 365-368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A., Nguyen M., Piotrowski T. (2010). Wnt/β-catenin dependent cell proliferation underlies segmented lateral line morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 349, 470-482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andermann P., Ungos J., Raible D. W. (2002). Neurogenin1 defines zebrafish cranial sensory ganglia precursors. Dev. Biol. 251, 45-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando R., Hama H., Yamamoto-Hino M., Mizuno H., Miyawaki A. (2002). An optical marker based on the UV-induced green-to-red photoconversion of a fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12651-12656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner J., Gribble S. L., Veien E. S., Nikolaus O. B., Weidinger G., Dorsky R. I. (2008). Proliferation and patterning are mediated independently in the dorsal spinal cord downstream of canonical Wnt signaling. Dev. Biol. 313, 398-407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha S. W., Tadjuidje E., Tao Q., Wylie C., Heasman J. (2008). Wnt5a and Wnt11 interact in a maternal Dkk1-regulated fashion to activate both canonical and non-canonical signaling in Xenopus axis formation. Development 135, 3719-3729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambly-Chaudiere C., Sapede D., Soubiran F., Decorde K., Gompel N., Ghysen A. (2003). The lateral line of zebrafish: a model system for the analysis of morphogenesis and neural development in vertebrates. Biol. Cell 95, 579-587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambly-Chaudiere C., Cubedo N., Ghysen A. (2007). Control of cell migration in the development of the posterior lateral line: antagonistic interactions between the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CXCR7/RDC1. BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsky R. I., Snyder A., Cretekos C. J., Grunwald D. J., Geisler R., Haffter P., Moon R. T., Raible D. W. (1999). Maternal and embryonic expression of zebrafish lef1. Mech. Dev. 86, 147-150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsky R. I., Itoh M., Moon R. T., Chitnis A. (2003). Two tcf3 genes cooperate to pattern the zebrafish brain. Development 130, 1937-1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizondo M. R., Arduini B. L., Paulsen J., MacDonald E. L., Sabel J. L., Henion P. D., Cornell R. A., Parichy D. M. (2005). Defective skeletogenesis with kidney stone formation in dwarf zebrafish mutant for trpm7. Curr. Biol. 15, 667-671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freese J. L., Pino D., Pleasure S. J. (2010). Wnt signaling in development and disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 38, 148-153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P., Hegerfeldt Y., Tusch M. (2004). Collective cell migration in morphogenesis and cancer. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48, 441-449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galceran J., Farinas I., Depew M. J., Clevers H., Grosschedl R. (1999). Wnt3a–/–like phenotype and limb deficiency in Lef1(–/–)Tcf1(–/–) mice. Genes Dev. 13, 709-717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamba L., Cubedo N., Lutfalla G., Ghysen A., Dambly-Chaudiere C. (2010). Lef1 controls patterning and proliferation in the posterior lateral line system of zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 239, 3163-3171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessert S., Kuhl M. (2010). The multiple phases and faces of wnt signaling during cardiac differentiation and development. Circ. Res. 107, 186-199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghysen A., Dambly-Chaudiere C. (2004). Development of the zebrafish lateral line. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14, 67-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghysen A., Dambly-Chaudiere C. (2007). The lateral line microcosmos. Genes Dev. 21, 2118-2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandel H., Draper B. W., Schulte-Merker S. (2000). Dackel acts in the ectoderm of the zebrafish pectoral fin bud to maintain AER signaling. Development 127, 4169-4178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryan T., Wend P., Klaus A., Birchmeier W. (2008). Deciphering the function of canonical Wnt signals in development and disease: conditional loss- and gain-of-function mutations of beta-catenin in mice. Genes Dev. 22, 2308-2341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas P., Gilmour D. (2006). Chemokine signaling mediates self-organizing tissue migration in the zebrafish lateral line. Dev. Cell 10, 673-680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. A., Cheng A. G., Cunningham L. L., MacDonald G., Raible D. W., Rubel E. W. (2003). Neomycin-induced hair cell death and rapid regeneration in the lateral line of zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 4, 219-234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani T., Matsumoto K., Chitnis A. B., Itoh M. (2005). Nrarp functions to modulate neural-crest-cell differentiation by regulating LEF1 protein stability. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 1106-1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter A. E., Azodi E., Marrs J. A., Liu Q. (2004). Cadherin-2 function in the cranial ganglia and lateral line system of developing zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 230, 137-143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B., Schilling T. F. (1995). Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 203, 253-310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre L., Soubiran F., Ghysen A., Konig N., Dambly-Chaudiere C. (2005). Cell proliferation in the developing lateral line system of zebrafish embryos. Dev. Dyn. 233, 466-472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre L., Ghysen A., Dambly-Chaudiere C. (2009). Mitotic patterns in the migrating lateral line cells of zebrafish embryos. Dev. Dyn. 238, 1042-1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecaudey V., Cakan-Akdogan G., Norton W. H., Gilmour D. (2008). Dynamic Fgf signaling couples morphogenesis and migration in the zebrafish lateral line primordium. Development 135, 2695-2705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. E., Wu S. F., Goering L. M., Dorsky R. I. (2006). Canonical Wnt signaling through Lef1 is required for hypothalamic neurogenesis. Development 133, 4451-4461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Ensign R. D., Azodi E. (2003). Cadherin-1, -2 and -4 expression in the cranial ganglia and lateral line system of developing zebrafish. Gene Expr. Patterns 3, 653-658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma E. Y., Raible D. W. (2009). Signaling pathways regulating zebrafish lateral line development. Curr. Biol. 19, R381-R386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda M., Chitnis A. B. (2010). Atoh1a expression must be restricted by Notch signaling for effective morphogenesis of the posterior lateral line primordium in zebrafish. Development 137, 3477-3487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins M. C., Nusslein-Volhard C. (1993). Mutational approaches to studying embryonic pattern formation in the zebrafish. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 3, 648-654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins M. C., Hammerschmidt M., Haffter P., Nusslein-Volhard C. (1994). Large-scale mutagenesis in the zebrafish: in search of genes controlling development in a vertebrate. Curr. Biol. 4, 189-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayoshi S., Hayashi E., Abe G., Osato N., Asakawa K., Urasaki A., Horikawa K., Ikeo K., Takeda H., Kawakami K. (2008). Insertional mutagenesis by the Tol2 transposon-mediated enhancer trap approach generated mutations in two developmental genes: tcf7 and synembryn-like. Development 135, 159-169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechiporuk A., Raible D. W. (2008). FGF-dependent mechanosensory organ patterning in zebrafish. Science 320, 1774-1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechiporuk A., Linbo T., Raible D. W. (2005). Endoderm-derived Fgf3 is necessary and sufficient for inducing neurogenesis in the epibranchial placodes in zebrafish. Development 132, 3717-3730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez V. A., Sarrazin A. F., Cubedo N., Allende M. L., Dambly-Chaudiere C., Ghysen A. (2009). Postembryonic development of the posterior lateral line in the zebrafish. Evol. Dev. 11, 391-404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R. (2008). Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Cell Res. 18, 523-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obholzer N., Wolfson S., Trapani J. G., Mo W., Nechiporuk A., Busch-Nentwich E., Seiler C., Sidi S., Sollner C., Duncan R. N., et al. (2008). Vesicular glutamate transporter 3 is required for synaptic transmission in zebrafish hair cells. J. Neurosci. 28, 2110-2118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin J. R., Talbot W. S. (2007). Signals on the move: chemokine receptors and organogenesis in zebrafish. Sci. STKE 2007, pe45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai K., Jafri I. F., Chidester S., James S. R., Karpf A. R., Cairns B. R., Jones D. A. (2010). Dnmt3 and G9a cooperate for tissue-specific development in zebrafish. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4110-4121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raible F., Brand M. (2001). Tight transcriptional control of the ETS domain factors Erm and Pea3 by Fgf signaling during early zebrafish development. Mech. Dev. 107, 105-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robu M. E., Larson J. D., Nasevicius A., Beiraghi S., Brenner C., Farber S. A., Ekker S. C. (2007). p53 activation by knockdown technologies. PLoS Genet. 3, e78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehl H., Nusslein-Volhard C. (2001). Zebrafish pea3 and erm are general targets of FGF8 signaling. Curr. Biol. 11, 503-507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahly I., Andermann P., Petit C. (1999). The zebrafish eya1 gene and its expression pattern during embryogenesis. Dev. Genes Evol. 209, 399-410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin A. F., Nunez V. A., Sapede D., Tassin V., Dambly-Chaudiere C., Ghysen A. (2010). Origin and early development of the posterior lateral line system of zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 30, 8234-8244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staal F. J., Luis T. C. (2010). Wnt signaling in hematopoiesis: crucial factors for self-renewal, proliferation, and cell fate decisions. J. Cell. Biochem. 109, 844-849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoick-Cooper C. L., Weidinger G., Riehle K. J., Hubbert C., Major M. B., Fausto N., Moon R. T. (2007). Distinct Wnt signaling pathways have opposing roles in appendage regeneration. Development 134, 479-489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungos J. M., Karlstrom R. O., Raible D. W. (2003). Hedgehog signaling is directly required for the development of zebrafish dorsal root ganglia neurons. Development 130, 5351-5362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin G., Haas P., Gilmour D. (2007). The chemokine SDF1a coordinates tissue migration through the spatially restricted activation of Cxcr7 and Cxcr4b. Curr. Biol. 17, 1026-1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veien E. S., Grierson M. J., Saund R. S., Dorsky R. I. (2005). Expression pattern of zebrafish tcf7 suggests unexplored domains of Wnt/beta-catenin activity. Dev. Dyn. 233, 233-239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz M., Christofori G. (2010). Mechanisms of motility in metastasizing cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 8, 629-642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.